Stewart Brand's Blog, page 7

July 29, 2022

How Humans Grew Acorn Brains

Human beings are quite capable of dealing with immediate crises. A devastating flood takes place and we send in the emergency relief. A pandemic occurs and we shut the borders and develop the vaccines. A war erupts and the refugees are found homes. More or less.

But when it comes to long-term crises, humanity’s record is less exemplary. Our response to the climate emergency – which is already here but whose greatest impacts are yet to come – has been painstakingly slow. We freely create technologies, from AI to bioweapons, that could pose devastating risks for our descendants. We fail to tackle deep problems like wealth inequality and racial injustice, which get passed on from generation to generation.

This temporal imbalance raises a question: is it even in the nature of our species to take the long view? Looking at the record so far, you would be right to be skeptical.

But there’s some unexpectedly good news: we are wired for long-term thinking like almost no other animals on the planet. As I argue in my recent book The Good Ancestor, grasping this scientific truth requires understanding the crucial difference between what I call the Marshmallow Brain and the Acorn Brain.

The Marshmallow Brain is an ancient part of our neuroanatomy, around 80 million years old, that focuses our minds on instant rewards and immediate gratification. This is the part exploited by social media platforms that give us dopamine hits by getting us to constantly click, scroll and swipe, as so brilliantly depicted in the film The Social Dilemma. It is named after the famous Marshmallow Test psychology experiment of the 01960s, where children who resisted eating a marshmallow for 15 minutes were rewarded with a second one: the majority failed.

There are well-known critiques of the test, for instance the fact that the ability to delay gratification is highly dependent on socioeconomic position: those from wealthier backgrounds find it easier to resist the treat, while a lack of trust and fear of scarcity can push kids towards gobbling it up.

A more fundamental critique, however, is that we are not simply driven by immediate rewards. Alongside the Marshmallow Brain we also possess a long-term Acorn Brain located in the frontal lobe just above our eyes, especially in an area known as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This is a relatively new part of our neuroanatomy – a mere two million years old – giving us a rare ability to think, plan and strategize over long timeframes.

But don’t other creatures think and plan ahead? Sure, animals such as chimpanzees make plans, like when they strip leaves off a branch to make a tool to poke in a termite hole. But they will never make a dozen of these tools and set them aside for next week.

Yet this is precisely what a human being will do. We are long-term planners extraordinaire. The Acorn Brain enables us to save for our pensions and write song lists for our own funerals. It’s how we built the Great Wall of China and voyaged into space. It’s why we’ll plant an acorn in the ground as a gift for posterity, like in the beautiful story The Man Who Planted Trees.

If we are going to tackle long-term challenges like the ecological crisis, we will need to use this unrivaled ability to become part-time residents of the future. Let’s recognize that we are not just short-term marshmallow snatchers, but long-term acorn planters.

The human capacity to think long term “is one of the brain’s most stunning innovations,” writes the psychologist Dan Gilbert, one of the founders of a newly emerging field called “prospective psychology.” But as he also points out, in evolutionary terms it’s a recent skill and we’re not very good at putting it into practice: we’re much better at ducking out of the way of a baseball thrown at our heads than at dealing with a danger whose biggest impacts are coming several years or decades down the line, like climate change.

Still, if we want to bring out the full potential of the Acorn Brain, we need to understand it better. Where did it come from and how does it work?

Evolutionary psychologists and archaeologists offer four main explanations for how our brains evolved this remarkable cognitive ability to think and plan over long timespans.

First is a survival skill known as “wayfinding.” Over a period of two million years our protohuman ancestors developed a capacity to orient themselves in physical space and navigate from place to place when they went on hunting or foraging expeditions, or roamed in search of shelter. In doing so they evolved an ability to create “cognitive maps” in their minds. But as University of Michigan ecologist Thomas Princen argues, this mental cartography required not just mapping place but also mapping time. Hunters could save precious energy – and even lives – if they not only planned the route but forward planned the time, identifying how long it might take to get from the stream to the forest and then back home again.

A second enabler of long-term brains, sometimes known as the “grandmother effect,” relates to the growing evidence that the presence of grandparents – especially maternal grandmothers – is important for reducing infant and child mortality. Recent research from anthropologists and evolutionary biologists reveals that older post-reproductive females provide vital childcare, knowledge and other forms of support that increase the survival chances of the young. Through this grandmother effect our ancestors became embedded in multigenerational kinship groups that helped them develop time horizons – and an ethic of care and responsibility – encompassing some five generations, stretching at least forwards by two and backwards by two from their own.

This was reinforced by the deep human instinct for social cooperation, which requires an imaginative capacity to see into the future. Relationships of trust and reciprocity work best when people know that the help they give to someone in the present will likely be returned at a future date, when they are in need themselves: time is woven into the fabric of mutual aid. Similarly, empathy is based on an ability to anticipate the needs, feelings and goals of others. When a friend loses her job, we may try to imagine what her emotional state might be and the best support we could give. In doing so we are prospecting the future by simulating an array of possibilities. Even the simple act of gauging someone’s intentions requires identifying different possible futures. As psychologist Martin Seligman points out, “How would we coordinate and cooperate if we could not form reliable expectations of what others would do in a range of situations?” The conclusion is clear: our social nature evolved in tandem with a talent for mental time travel.

A final explanation concerns the human genius for toolmaking. Over two million years, our capacity to make stone tools became increasingly sophisticated. The earliest tools simply had natural points and edges. But then our Paleolithic ancestors learned to flake off part of the stone by hitting it against a surface, and eventually made three-dimensional tools where multiple planes met at a single point. Creating these wasn’t just a matter of randomly bashing off bits of stone: it required forward planning and envisioning future goals. According to historian of technology Sander Van der Leeuw, as our brains grew and we developed the ability to make complex tools, we also developed “the capacity to plan and execute complex sequences of actions.” The ability to plan making a stone tool enabled us to plan other forward-looking actions with long time horizons such as crop rotation or building a pyramid. All those stone tools gathering dust in museums reveal the greatest of all human achievements: the emergence of civilization itself.

The human brain is designed for so much more than constantly checking our phones. With an understanding of these four origins of our long brains, we have the beginnings of a new story about human nature. We are not merely prisoners of our Marshmallow Brains but have Acorn Brains wired into us. We have evolved with a unique ability to plan over long time periods. That’s what enabled medieval cathedral builders to embark on projects they knew might never be completed within their own lifetimes. Such “cathedral thinking” is precisely what we urgently need today to tackle the long-term ecological, political and technological challenges of our time.

Narratives about human nature matter. Studies of economics students have shown that those who are taught that human beings are essentially rational, self-interested creatures are more likely to act selfishly after completing their courses than their freshman counterparts. It’s time to get the narrative about our temporal selves right. Let us embrace the Acorn Brain as part of who we are and recognize it as a vital foundation for creating a long-now civilization, where we take responsibility for the impacts of our actions on the citizens of tomorrow.

—

Roman Krznaric is a public philosopher. His latest book is The Good Ancestor: A Radical Prescription for Long-Term Thinking.

July 26, 2022

Building Nature at Silver Falls

If there's an overused word when it comes to describing natural areas, it's pristine. Whenever the term is deployed, the implication is clear: people want a place "untrammeled by man." Too much human activity disqualifies a place in the eyes of many, even though our most "pristine" natural areas are today at risk from global environmental threats. This dichotomy of pristine vs. spoiled nature can't hold up any longer. Looking at the historical trajectory of Silver Falls, now a state park in the heart of Oregon, helps us to interrogate what it is that we want from state parks and natural areas, and how active efforts to restore and build natural areas can create more robust environments than preservation alone.

Location of Silver Falls State Park in Marion County, Oregon, United States. Graphic by Casey Cripe. Image source: Oregon State Parks

Location of Silver Falls State Park in Marion County, Oregon, United States. Graphic by Casey Cripe. Image source: Oregon State ParksThe South Falls at Silver Falls State Park makes for one of the prettiest vistas in the state of Oregon. With water falling 177 feet from above, visitors to the park can follow a trail behind the fall before starting on the Trail of Ten Falls, a five-mile loop through the park. The park itself is the largest and one of the most popular parks in the state. Located near the town of Silverton and approximately an hour and a half away from the city of Portland, it’s easily accessible for most of the state’s population. It’s a popular site for film crews looking for Pacific Northwest forests: the live-action Yogi Bear was filmed there, as was Twilight, though of course the park cannot be held responsible for the quality of said films.

Map of the Trail of Ten Falls, from a 20th century printed brochure. Image source: Oregon State Parks

Map of the Trail of Ten Falls, from a 20th century printed brochure. Image source: Oregon State ParksHowever, Silver Falls looked very different a century ago. In 01931, South Falls was a tourist attraction, but not for the beauty of the falls. Instead, the owner, Dan Geiser, charged audiences a quarter a person to watch as he dropped automobiles down the falls. Multiple fires had raged through the park in the 01880s. A small town had existed there previously, but by the 01930s it was largely abandoned. A few failing farms dotted the landscape of Silver Falls, though most of them were selling out to logging concessions. Ill-suited for farming, logged over, and remote because most of the state’s highways were still under construction, Silver Falls was neither pristine wilderness nor especially beautiful.

A local photographer named June Drake documented the area through his photography and helped to create awareness of the falls, but his attempts to protect it were running into considerable difficulty. He paid to have the first trails cut around the falls to make them accessible to other visitors, but the damage that was done to the landscape was beyond his ability to fix. In photos from the 01920s, Drake’s shots of the falls were beautiful, but also captured stumps, burned over areas, and dead trees, the result of heavy fires that had raged through Silver Falls years before.

June Drake's 01925 photograph of South Falls features a landscape ravaged by fire. Oregon Historical Society (OHS) digital no. bb007812

June Drake's 01925 photograph of South Falls features a landscape ravaged by fire. Oregon Historical Society (OHS) digital no. bb007812Overlogging and farming wasn’t just harming the aesthetics of the area: it also posed a serious risk to its long-term future. Residents had lit brush fires to clear land for farming, destroying most of the old-growth forests in the park. Silver Falls today is close to 9,000 acres, but in 01931, probably just a few hundred acres of old-growth forests remained. Logging was also threatening the watershed for the creek that fed the waterfalls, casting the long-term future of the falls themselves into doubt.

Drake had nominated the area to be a National Park in 01926, but an NPS inspector rejected the site as not being suitable for that designation. It was too heavily logged over and farmed, in the opinion of the inspector. Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane had written in 01918 that national parks had to have “scenery of supreme and distinctive quality or some natural features so extraordinary or unique as to be of national interest and importance.” Natural areas had to be outstanding, and moreover, they could not be too damaged or used by human beings. To admit anything less than the outstanding risked undermining the whole park system.

The effects of logging in the Silver Creek watershed, photographed by June Drake. Source: Drake Bros. Studio Photograph Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

The effects of logging in the Silver Creek watershed, photographed by June Drake. Source: Drake Bros. Studio Photograph Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University LibraryThrough negotiations with the nearby Salem Chamber of Commerce, Drake convinced them to buy parcels of land around Silver Falls and then turn them over to the state to create a state park. Silver Falls was created as a state park in 01933, but it remained small, and the land was still heavily damaged from decades of logging and farming. Fortunately for Silver Falls, the election of Franklin Roosevelt to the presidency changed the relationship of the federal government with the states, and at least temporarily, with the natural environment.

Roosevelt became president amid multiple disasters, most conspicuously the Great Depression. In addition to a 25% unemployment rate and a wave of bank failures that were annihilating people’s savings, the United States also faced multiple environmental crises in the 01930s. The Dust Bowl was perhaps the most destructive of these: struck by drought, midwestern states saw much of their topsoil turn to dust and simply blow away, creating dust storms that reached as far as Boston and New York. But there were other disasters as well. Flooding along the Ohio River displaced thousands of people in March of 01933, and forest fires threatened the Pacific Northwest.

Winter Falls surrounded by trees damaged by fire, photographed by June Drake. Source: Drake Bros. Studio Photograph Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Winter Falls surrounded by trees damaged by fire, photographed by June Drake. Source: Drake Bros. Studio Photograph Collection, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University LibraryRoosevelt’s response was to create a series of government agencies that would actively manage the natural environment. The most famous of these was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), modeled after a similar system Roosevelt had implemented as governor of New York. The CCC enlisted young men between the ages of 18 and 25 (with smaller programs for Native Americans and WWI veterans), paying them $25 a month as well as room and board, and put them to work on various nature conservation projects. Ultimately, the CCC employed more than three million people over nine years, and in that time they built up a long list of accomplishments: three billion trees were planted, millions of acres of farmland were protected through soil erosion programs, and thousands of lakes and streams were protected. And, of course, they built parks.

The CCC arrived at Silver Falls in 01935 and built on earlier short-term construction projects done by other New Deal agencies. Several CCC camps worked at the site between 01935 and 01942, when the outbreak of WWII brought an end to the national CCC. Some of their work dealt with cutting trails, building summer camps for Oregon children, and building other park structures. The more important work, however, was restorative. One of their chief jobs was reforesting the area around the falls. With most of the old-growth forest gone, new trees would have to be planted to rejuvenate the forest and protect the watershed along with the falls.

Instead of replanting the park with the original trees, the CCC opted to use Douglas fir and western hemlock that would regrow quickly and propagate. Ultimately, thousands of acres were reforested. In conjunction with that work, CCC workers also constructed firebreaks, removed underbrush, and built infrastructure to help fight future forest fires – no trivial concern, given that the Tillamook Burn in Oregon had burned through hundreds of thousands of acres of forest in 01933. These firebreaks were not natural (and interfered with expected fire ecology for a western forest), but they were judged to be needed for the long-term survival of the park.

Early 20th century visitors of the new Silver Falls State Park take in the natural wonder of South Falls, the park's most iconic waterfall. Photographed by June Drake. OHS digital no. bb007810

Early 20th century visitors of the new Silver Falls State Park take in the natural wonder of South Falls, the park's most iconic waterfall. Photographed by June Drake. OHS digital no. bb007810What does Silver Falls mean when we think about the idea of the long-term, especially about natural areas? It was part of a larger national environmental movement, the first of such size and scope in the United States, and one that saw all natural areas in the country as resources that needed to be tended to. The problem was that this environmental movement didn’t go far enough. The mobilization for World War II ended the CCC, but the underlying need for something like it never went away. The same places that suffered from the Dust Bowl in the 01930s underwent terrible droughts in the 01950s as well; the solution, instead of better practices around soil erosion, was to simply pump groundwater.

Silver Falls also illustrates how impermanent the natural areas we choose to value really are, especially because of human activity. Euro-American settlement had heavily damaged the land around Silver Falls: whatever it had been before the 19th century was long gone, and it had to be rebuilt and reimagined. What people wanted from parks shifted as the 20th century went on. In the 01960s, attention shifted toward wilderness preservation, perhaps most famously through the 01964 Wilderness Act. The goal of wilderness preservation was to leave places untouched: park development like Silver Falls fell out of favor in light of preserving “pristine” wilderness. Building lodges and concession buildings or reforestation work was seen as too heavy of a hand.

Iconic South Falls, still attracting visitors (and photographers) well into the 21st century. Bureau of Land Management, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Iconic South Falls, still attracting visitors (and photographers) well into the 21st century. Bureau of Land Management, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, “pristine” wilderness never really existed: it erased indigenous people from their land. It creates arbitrary distinctions between humans and nature, whereas parks like Silver Falls sought to bring humans into nature. Even the architectural style, part of that classical Arts & Crafts park style from the mid-20th century, was supposed to merge human buildings with nature. And the focus on “outstanding” or “singular” beauty nearly left Silver Falls behind and unrehabilitated.

Moreover, the reality of climate change is going to alter every natural area around the globe -- returning them to prior idealized states is going to be impossible. And it’s a reminder that over time, what is or isn’t natural can shift dramatically: the secondary growth forests at Silver Falls will eventually become old growth if you simply wait long enough. It’s not enough to preserve natural areas as they are: in some cases, they need to be rethought or reworked. With the benefit of better ecological science than the CCC had in the 01930s, this can be done.

July 19, 2022

Alicia Eggert

Interdisciplinary artist Alicia Eggert and Long Now's Executive Director Alexander Rose will be in conversation for this special evening discussion of time, art and long-term thinking. More details will announced soon, including location.

In the meantime, you can read Long Now Managing Editor Ahmed Kabil's 02021 interview with Alicia Eggert.

July 18, 2022

Fandom Relics and the Enthusiastic Past

Fandom, in 02022, is big business. Corporations court it, social media platforms are dominated by it, and a large proportion of Gen Z participates in it. It is a lens through which many of the most controversial movements of the last decade can and have been viewed: Gamergate, the alt-right, the Depp v. Heard trial. It’s “a history-shaping force that we’d be foolish to ignore,” and the source of much of contemporary culture’s most fervent and fertile outpourings.

But it didn’t come out of nowhere. Like any subculture it has origins; a history; an evolutionary tree full of hairpin turns, dead ends, and forgotten curiosities. Fandom is often the first to take up new technologies, and develop new and creative ways to express itself. But in moving so quickly, especially in the social media age, it has a tendency to forget itself. Generation gaps can yawn in between different “eras” of fandom, causing even the recent past to fall into darkness — a darkness which every so often receives a flash of illumination.

In May 02022, Tumblr user gar-trek posted about a thrift store discovery: “never forget when i found a random star trek zine at the antique store and there was kirk mpreg in it and i was like ’excuse me’ and when i looked up the zine on google it was like ‘includes what could be the first-ever instance mpreg fanart!!’ like why do i own the first ever mpreg fan art ever made. why.” The art depicts a heavily pregnant Captain Kirk speaking to Spock, referencing a well-known slash (male/male) fanfiction story of the era. The response on Tumblr to the discovery was rapturous: many a reply asserted something along the lines of “I don’t even like mpreg, but this is so important.”

Fanart of Star Trek's Captain Kirk that was discovered in a thrift store. Source: gar-trek (Tumblr)

Fanart of Star Trek's Captain Kirk that was discovered in a thrift store. Source: gar-trek (Tumblr)Another post about a piece of early piece of fanart depicting Kirk, Spock, and Bones in a three-way relationship (also known as an OT3) from the 01970s also discovered in a thrift store brought up similar emotions amongst the general fandom audience on Tumblr. Even those who claimed not to be Star Trek fans or to not care about the show commented on how they were affected by the discoveries. And user undeadhousewife was moved to muse, “I am legitimately curious what modern fandom would even look like with out Star Trek.”

01970s fanart depicting Star Trek's Captain Kirk, Spock, and Bones in a three-way relationship. Source: brofisting (Tumblr)

01970s fanart depicting Star Trek's Captain Kirk, Spock, and Bones in a three-way relationship. Source: brofisting (Tumblr)It’s true that Star Trek forms a major basis of most of what fan studies scholars would consider the world of “Western media fandom” — that amoebic grouping of fan culture that can be traced back to 01970s hand-copied zines and in-person conventions, centering around American and British television shows like Starsky & Hutch, The Professionals, and Blake’s 7. These communities went digital in the 01990s and eventually merged with other types of fandoms in the melting pot of the internet — pop music fandom, Japanese media fandom, science-fiction literature fandom, among others.

There’s a regrettable tendency amongst teenagers in fandom to assume that the fandom switch inside your head will just “turn off” when you hit a certain age. But any fan in their 30s, 40s, or 50s could tell you that’s not the case. If you’re a Star Trek fan, you probably know this, thanks to the fandom’s longevity and continuity, which is helped along by fans who remember the early days and wish to make sure others remember too. Fandom Grandma, a.k.a. Dee, a woman in her late 70s, took the time to share stories of her early days in 01960s Star Trek fandom via Tumblr before she passed away in 02018. She was mourned widely by Tumblr users who treasured her tales of the first slash fiction zines and the time Leonard Nimoy came to a fan club meeting.

But if a fan isn’t part of a fandom like Star Trek or those mentioned above, with histories that stretch back past the digital age, it’s not particularly likely that any given fan is aware of what their fannish forerunners were up to. While it used to be common practice to befriend fans much older than you, who could be resources to learn about fandom history (that is to say, history of your fandom in particular as well as fandom in general), that’s not as frequently the case today. It’s easy to spot fans on Twitter under the age of 18 with “23+ DNI” (people over the age of 23 Do Not Interact”) in their profiles, or the reverse: adult fans with a “minors DNI” sign. In many spaces a taboo on intergenerational interaction has arisen, or at the very least a heavy distaste for it. There’s a general suspicion of older fans: it seems wrong somehow to many young fans that they would be allowed or encouraged to enjoy things in the same way when they’re “all grown up,” and so they look down on those who are doing exactly that. This phenomenon causes further damage to continuity within fandom.

The fact that assorted artifacts from the 01970s seem very much like relics of an ancient time speaks to the relative newness of fandom as a phenomenon capable of leaving things behind. But there are examples that stretch back even further than Star Trek, like an anecdote about a Japanese diary written during the Meiji era full of historical-figure slash fiction. In the replies to that anecdote someone linked what they called an “ancient Chinese fujoshi”: a Qing-era illustration titled “Woman spying on male lovers.”

Like this great-grandmother which lived in the MEIJI period wrote a novel about two historical characters being gay for each other

— shipper ㋐ stan vampire Jesus 🥀🌹✨🐍🍽️🐸🐸🏳️🌈㋐ (@shipperinjapan) June 21, 2019

Japan had fanfic culture 150 years before the rest of the world 😂😂😂

Discoveries of relics like early Star Trek fanart are reminders that fandom has a history extending beyond back past the internet, made by individuals, each with their own passions and obsessions. As Tumblr user polyhexian puts it, “It's like how historians get more excited about finding an ancient shepherds diary than a historical textbook.” Fandom as a feeling can sometimes seem overwhelmingly ephemeral and changeable. Sometimes this can be a good thing, contributing to creativity and spontaneity. But with knowledge and practices increasingly difficult to pass directly from generation to generation amongst constant platform migrations, as well as increased siloing of the older from the younger, a fan can too easily believe themselves to be a product purely of the present, and instead of a step in a chain stretching back centuries and continuing on far into the future.

Preserving fandom’s past for the benefit of the future is a subject receiving increased attention. The zine archive at the University of Iowa is a physical trove of printed matter from the history of 20th-century media fandom. The expansive Fanlore.org, a project of the Organization for Transformative Works, is a massive repository of fandom knowledge, written by and for fans. But a great deal of the links that they catalog are dead; and as people move in and out of different fandoms and the subculture itself, things are erased, left behind, and forgotten.

An issue of The Science Fiction Fan (ca. 01939-40) housed in the University of Iowa's zine archive. Source: Hevelin Collection, University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archives.

An issue of The Science Fiction Fan (ca. 01939-40) housed in the University of Iowa's zine archive. Source: Hevelin Collection, University of Iowa Special Collections & University Archives.Not much stays in one place for one long, especially when it comes to digital artifacts. When the Yahoo Groups archive was summarily deleted by parent company Verizon just a few years ago, fandom suffered massive losses, just as it had during the Livejournal purges of the late 02000s, and during the Tumblr porn ban in 02018. Fandom preservation, then, ties into the larger issue of digital preservation as a whole, and specifically the question of how individual and group emotions and experiences — which make up so much of what it means to be a fan — can be effectively documented, annotated, and saved.

There has of late been a surge in people experimenting with printing and binding fanfiction. Members of the fanbinding community, as they’re known, are well aware that the works they’re printing are freely available on the web, and are also technically illegal to sell and buy. Printing out one’s favorite stories and lavishly binding them in leather and gold is not only an expression of fannish affection; it’s also a way of ensuring that they are preserved in stable physical form. Even though the Archive Of Our Own, also run by the OTW, was founded with the express intention of preventing the kind of losses that have struck fan archives in the past, there is still something valuable in expending time and effort to bring fanfiction to life as a book: one that might well be discovered in a thrift store in some unknown future, and posted about for other fans to marvel at. Fanbinding preserves both the work itself and the original fannish passion that sparked the urge to make the bound version in the first place.

Lot of progress this weekend. About 12 volumes in the works. #bookbinding pic.twitter.com/IUte6C5VDy

— ArmoredSuperHeavy - Dead Dove Publishing 💀🕊️🍴 (@ArmoredHeavy) March 4, 2019

There’s no clear solution to the ongoing issue of fandom’s intergenerational issues with memory and continuity, but the spotlighting of discovered relics and the ongoing preservation of artifacts, both digital and physical, is a good starting point. Algorithmic platforms make it all too easy to live totally in the moment, which is as dangerous within fandom as anywhere else.

And as a subset of cultural memory in general, fandom memory is essential if we are to understand how the practices of mass enthusiasm that are now coming to dominate culture as a whole have taken shape. Superhero franchises and pop stars rely on fandom, as do the companies behind them. Surely these giants of culture don’t need any help being remembered, but the ways that fandoms respond to them — whether with love, hate, obsession, transformation — are just as vital to preserve.

July 14, 2022

E. coli in the Long View

E. coli lives in the short now. Like many of its bacterial peers, Escherichia coli can take as little as twenty minutes to reproduce in ideal laboratory conditions. Despite these brief individual lives, E. coli, an impressively diverse bacterial species that includes both harmless and rather harmful strains, has a long history that intertwines deeply with humans and our guts. Two recent scientific studies — one reaching centuries back and another observing thousands of generations’ worth of evolution in the now — provide important insight into the past, present, and future of our sometimes contentious relationship with E. coli.

The first study, published this month in Communications Biology, uses an unlikely source to uncover the oldest genome of E. coli as of yet found. The study, which comes from a team of international scientists, drew its sample of E. coli from a gallstone found in the mummy of Giovanni d’Avalos, a middle-aged Neapolitan nobleman who died in 01586. d’Avalos lived an unremarkable life: unlike his father Alfonso, who served ably under Spanish King and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in the Italian wars, d’Avalos received no great distinction in his forty-eight years of life in and around Naples and the Southern Mediterranean. Instead, history and biology remember him for the swath of health conditions he acquired in his last decade of life, including most notably an acute case of cholecystitis, the inflammation of the gallbladder.

Giovanni d’Avalos's remains – with detail on his gallstones. Courtesy of Long et al, 02022, Creative Commons Attribtuion International 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Giovanni d’Avalos's remains – with detail on his gallstones. Courtesy of Long et al, 02022, Creative Commons Attribtuion International 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.Gallstones have many possible causes, but E. coli is among the most prominent. And in the long-buried gallstones of Giovanni d’Avalos, the researchers found exactly that. After extracting genetic material from the still-preserved, dark brown gallstones and filtering out human DNA, the researchers found that the most common bacterial species present in the DNA samples was E. coli.

From there, the study explores how these sixteenth century microbes differ from their modern relatives. How have the untold hundreds of thousands or millions of generations reshaped the E. coli genome? The researchers found that the gallstone E. coli sample had DNA that fit best in the species’ Phylogroup A, a clade within the species associated with other historical strains, strains found in less industrialized communities, and gout-causing strains.

Yet the d’Avalos sample differed in significant ways from A-group E. coli of more recent vintage. For one, they lacked the array of antimicrobial resistance genes that contemporary strains usually carry. The people of early modern Italy did not have easy access to effective antibiotics, which were only invented in the 01930s — . The particular variety that found its way into d’Avalos’ gallbladder also lacked many of the virulence factors associated with common harmful strains like Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, indicating it was instead a commensal strain — typically benign in human bodies — that made an opportunistic leap into gallstone infection in a time of bodily stress. Most studies that have explored ancient DNA have focused on more obvious pathogens like Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that caused the Black Plague and many subsequent epidemics. By analyzing a more benign set of pathogens, the study opens up the door to a deeper understanding of how our microbial passengers have evolved with us.

The other recent E. coli study is less ancient in its provenance, but no less an example of long-term thinking in our understanding of our microbial counterparts. It draws on one of the most significant long-form experiments in biological history: the E. coli long-term evolution experiment (LTEE), which has been running for nearly 35 years since its 01988 inception at Richard Lenski’s laboratory at the University of California, Irvine. Since then, the experiment has moved with Lenski to Michigan State University, where the strains of bacteria involved in the experiment lived for more than three decades. As of June 02022, the experiment has withstood yet another move to Jeffrey Barrick’s lab at the University of Texas at Austin.

The twelve lineages of Lenski's Long-term Evolution Experiment in 02006. Courtesy of Brian Baer and Neerja Hajela, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 1.0 Generic

The twelve lineages of Lenski's Long-term Evolution Experiment in 02006. Courtesy of Brian Baer and Neerja Hajela, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 1.0 GenericThe LTEE’s set-up is potent in its simplicity. In 01988, Lenski set up 12 populations of (non-pathogenic) E. coli, beginning from a single haploid cell each, in 12 identical glucose solutions — enough nutrients for the bacterial populations to grow 100-fold in a few hours. Every day since, lab members have transplanted 1% of the prior day’s population to a new set of media, allowing the cycle to continue anew. To keep a record of the experiment’s evolutionary development, each population is frozen every 500 generations (approximately every 75 days) using a cryoprotectant for protection and stored at -80° F, a fossil record of samples that can be reawakened for further study, in a process that the lab considers a sort of “time travel.”

A timeline of the LTEE with generation times for comparison

A timeline of the LTEE with generation times for comparisonThe experiment, originally intended to track evolution for 2,000 generations, has now been running for more that 75,000 generations. To put this in more familiar terms, that’s the generational distance between modern-day humans and Homo erectus. It hasn’t been a constant run over the course of its three-plus decades; the beginning of the Coronavirus Pandemic in 02020 and, less catastrophically, the move from Irvine to Lansing, Michigan in 01992 caused interruptions of six months each.

Despite these short breaks, the experiment’s extreme longevity has allowed for a wealth of scientific discovery in the form of more than 150 scientific publications from 01991 until this year. In a recent interview, Lenski noted that the experiment has shown both evolution’s reproducibility and the “striking divergences” it can produce. While the 12 lines have shown similar overall increases in fitness relative to the baseline ancestor, they have not all followed the same path, with one out of twelve having evolved the surprising ability to consume citrate in addition to glucose around generation 31,500.

The most recent paper out of the LTEE, by post-doc Minako Izutsu and Lenski, tests one of the foundational questions of evolution: the comparative roles of initial genetic diversity and future mutations in determining fitness. Variation within a population is a necessary fuel for natural selection — without it, there’s nothing to select for — but that variation can come from two sources in a controlled experimental environment. Variation can be baked into a study due to the initial mix of individuals in an experimental population, or can arise through mutation as it progresses. Izutsu and Lenski’s study explores whether initially non-diverse populations can “catch up” to their more diverse counterparts in terms of fitness. It compares 4 different treatments of bacteria: cloned samples with no initial diversity, lines from 50,000 generations into the LTEE, and mixed versions of both the clones and the lines.

Over the course of the 2,000 generations of the experiment, the 72 lines in the new experiment all gained similar amounts of relative fitness. During the first 100 generations, the more diverse, mixed lineages adapted to new conditions much more quickly, but by the 500th generation this initial advantage wore away as mutations occurring during the experiment proved to have a more long-lasting effect.

The experiment’s results, and perhaps the grander enterprise of the LTEE itself, speak to the power of evolutionary time to break through what may seem like immutable starting characteristics. E. coli has been with us for untold generations — more of theirs than ours, to be sure — and we have evolved together in both commensal and adversarial ways. Whether in noble gallstones or controlled lab conditions, E. coli will continue to evolve with us.

November 17, 2021

The Future and the Past of the Metaverse

In the mid-2000s, the virtual world of the game Second Life was seen by many as a nascent metaverse, a term for virtual worlds coined by Neal Stephenson. Courtesy of Jin Zan CC-BY-SA-3.0

In the mid-2000s, the virtual world of the game Second Life was seen by many as a nascent metaverse, a term for virtual worlds coined by Neal Stephenson. Courtesy of Jin Zan CC-BY-SA-3.0Sometime in the late 01980s or early 01990s, five-time Long Now Speaker Neal Stephenson needed a word to describe a world within the world of his novel Snow Crash. The physical world of Snow Crash is a dystopia, dominated by corporations and organized crime syndicates without much difference in conduct. The novel’s main characters are squeezed to the fringes of the “real world,” forced to live in storage containers at the outskirts of massive suburban enclaves. The small salvation of this future is found in the online world of the “metaverse,” described first as “a computer-generated universe that his computer is drawing onto his goggles and pumping into his earphones.” A page later, Stephenson expands this description out, waxing rhapsodic about the main thoroughfare of the metaverse:

The brilliantly lit boulevard that can be seen, miniaturized and backward, reflected in the lenses of his goggles. It does not really exist. But right now, millions of people are walking up and down it. […] Like any place in Reality, the Street is subject to development. Developers can build their own small streets feeding off of the main one. They can build buildings, parks, signs, as well as things that do not exist in Reality, such as vast hovering overhead light shows, special neighborhoods where the rules of three-dimensional spacetime are ignored, and free-combat zones where people can go to hunt and kill each other. The only difference is that since the Street does not really exist—it’s just a computer-graphics protocol written down on a piece of paper somewhere—none of these things is being physically built. They are, rather, pieces of software, made available to the public over the worldwide fiber-optics network. When Hiro goes into the Metaverse and looks down the Street and sees buildings and electric signs stretching off into the darkness, disappearing over the curve of the globe, he is actually staring at the graphic representations — the user interfaces — of a myriad different pieces of software that have been engineered by major corporations.

Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash pp 32-33

The idea of the metaverse — of a virtual, networked world as real as our own physical one — was not completely original. A few years prior, William Gibson had used the term “cyberspace” in his own science fiction stories. In Gibson’s work, cyberspace is “A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts… A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding.”

The distinction between Stephenson’s metaverse and Gibson’s cyberspace is one of tangibility. Cyberspace defies human understanding, with Gibson’s description evoking the abstract and hallucinatory. The metaverse is instead clearly bounded within the human experience, replicating it in another place but keeping its visual language and structure — city streets, defined bodies, neon signs.

This is perhaps why the metaverse has been so captivating as a concept for as diverse a range of figures as hackers, critical theory academics, and tech billionaires. It’s futuristic, expanding the possibilities of human expression and enterprise, but it does not break so fully from the human as certain similar visions. It’s a far step from Gibson’s cyberspace or a vision of the technological singularity in line with the views of past Long Now Speaker Ray Kurzweil. It’s the future, but it’s a familiar future.

Yet the claimants of the banner of the metaverse post-Snow Crash are not united in their visions. Many of the first writers and thinkers to explore the conceptual landscape afforded by the idea of the metaverse were skeptical of whether it would truly be liberatory. The feminist comparative literature scholar Marguerite R. Waller asked in 01997 if the interface of a hypothetical virtual reality metaverse would “be the site of a seduction away from Western logocentrism or of a more subtle, deep-seated entrenchment?” Similarly, the literary scholar Philip E. Baruth notes in a reflection on race (and its omission) within the cyberpunk world that “A person entering the Metaverse, like an infant entering the real world, is already bound by the agreed upon language of the Protocol, as well as the ethical view of the world represented by that web of social determinants.”

Those in the tech world who have recently taken to using the term metaverse seem less interested in these ethical and theoretical quandaries. Instead, they are mostly focused on the experience of the metaverse and how they can profit off of it. In the most discussed corporate re-branding of the year, social media company Facebook renamed itself “Meta,” with founder Mark Zuckerberg explicitly announcing that the company’s focus was now to “bring the metaverse to life and help people connect, find communities, and grow businesses.” For now, at least, the details of Meta’s metaverse are hazy – mostly focuses on shifting conference calls into virtual boardrooms, which is perhaps not as dramatic as anything foretold in Snow Crash.

Along with Meta-née-Facebook, companies like NVIDIA, previously known mostly for GPUs, and tech giant Microsoft have made much hay about moving into the metaverse. In both cases, the connection is more prosaic than fantastical: NVIDIA claims that their graphics infrastructure could provide an “omniverse” to connect portions of the metaverse, while Microsoft sees the metaverse as a tool to “help people meet up in a digital environment, make meetings more comfortable with the use of avatars and facilitate creative collaboration from all around the world.”

Microsoft’s announcement even explicitly acknowledges that their metaverse is “not the metaverse first imagined” in Snow Crash. Yet it is unclear what real metaverse could ever match with the precise dynamics of Stephenson’s fictional one. It is also unclear if fidelity to Stephenson’s vision is necessary for any future metaverse. The idea of a metaverse is still in its infancy — thirty years is not so long in the pace layers of culture, governance, and infrastructure that the metaverse would operate in — and the actual practice of building a metaverse is even younger than that. Our imaginations of the metaverse, whether dreamed from the corporate world, the academy, or somewhere beyond, will inherently fail to capture the rich actuality of the metaverse yet to come.

October 28, 2021

Stewart Brand Takes Us On “The Maintenance Race”

Bernard Moitessier’s yacht Joshua was the model of perfect maintenance in his 1968 circumnavigation of the globe

Bernard Moitessier’s yacht Joshua was the model of perfect maintenance in his 1968 circumnavigation of the globeMaintenance is all around us. On every level from the cellular up to the societal, human life is driven by the essential drama of maintaining, of ensuring continued survival and working against the drive of entropy.

Yet maintenance is a largely unheralded presence in our lives. We are fascinated with the people who begin great works — from ancient rulers who ordered the building of pyramids and other great monuments to tech founders who announced revolutionary devices. The maintainers downstream of those grand beginnings, the craft workers who made sure the rock-hewing tools remained sharp or the software engineers pushing patches to cover every new security vulnerability, get short shrift in our cultural memory. Who’s the most famous maintainer you can name?

At The Long Now Foundation, we care deeply about maintenance. The prospect of the 10,000 Year Clock relies more on its maintenance than its building: if its mechanism is not wound every 500 years, it will not continue to run. Over the course of its lifetime, it will remain in its maintenance phase for far longer than it spent being built.

The Clock is an obvious example of the value of maintenance. Long Now Co-Founder Stewart Brand’s upcoming book on maintenance hones in on more examples, collected from history and the world around us. Its first chapter, out now as an audiobook on Audible, tells the story of the 01968-01969 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, the first solo, non-stop yacht race around the world. It’s a story that’s been told again and again since 01969.

The retellings of the race usually focus on the daring and grit of its nine competitors. Stewart Brand’s The Maintenance Race instead focuses on the different approaches to maintenance that the three most famous (or infamous) racers took.

The eventual victor, Robin Knox-Johnston, brought with him a wealth of experience in the merchant navy that gave him a genuine enthusiasm for maintaining his vessel. Brand quotes Knox-Johnston, who, months into the “endless ordeal” of repair, noted: “I realized I was thoroughly enjoying myself.”

The cheat who perished in his attempt, Donald Crowhurst, was a brilliant inventor with perhaps the most technologically advanced boat. His failure and despondency were driven by his initial optimism and belief in elegant solutions. Brand, an optimist himself, notes that optimists “frequently resent the need for maintenance and tend to resist doing it,” instead preferring to live in the world of ideals rather than the drudgery of constant tasks.

The final sailor of Brand’s chosen three, Bernard Moitessier, defies easy characterization. He was perhaps the most impressive sailor of the group, on pace to win handily, but he did not finish. Instead, he kept on sailing, taking a longer route to Tahiti. Moitessier pared down his racing set up to the bare minimum — the less stuff you have, the less stuff you have to maintain. His decades of experience honed his designs down to fine, easy to maintain points: a steel hull reinforced with seven coats of paint to prevent corrosion, a slingshot for communications rather than a heavy, complex radio system, warm clothes instead of a heating system. His philosophy was one of simplicity. “Only simple things,” he later recalled, “can be reliably repaired with what you have on board.”

Bernard Moitessier’s voyage set the record for the longest non-stop voyage in a yacht thanks to his devotion to preventative maintenance. © Sémhur / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0, translated by Jacob Kuppermann

Bernard Moitessier’s voyage set the record for the longest non-stop voyage in a yacht thanks to his devotion to preventative maintenance. © Sémhur / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0, translated by Jacob KuppermannWhile Knox-Johnston won the official race, Moitessier won the Maintenance Race — his philosophy of maintenance, which he once related to Brand as “A new boat every day,” exemplifies how preventative maintenance can lead to a certain “undefinable state of grace,” a focus and serenity that can be hard to find.

The first chapter of Brand’s book is full of remarkable details of the three racers’ journeys, but perhaps the most exciting part is the rest of the book it foreshadows, still unwritten. The philosophy of maintenance that The Maintenance Race begins to outline resounds throughout the human experience, and Brand’s book promises to trace maintenance through different scales with compelling stories.

Learn More:Listen to the first chapter of Brand’s book as read by Richard Seyd, on Audible here.Watch Nadia Eghbal’s talk on the Making and Maintenance of Open Source InfrastructureRead Ahmed Kabil’s article on the maintenance of the White Horse of Uffington for a 3,000 year case study on the power of maintenance.

The Future of Progress: A Concern for the Present

A sign from the No Planet B global climate strike in September 02019. Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

A sign from the No Planet B global climate strike in September 02019. Photo by Markus Spiske on UnsplashThe following essay was written by Lucienne Bacon and Lucas Kopinski, senior year students at Avenues: The World School . Bacon and Kopinski spent the previous school year engaging with Long Now ideas, such as the pace layers model, while they pursued an independent project reflecting on the importance and fallibility of metrics when it comes to balancing long-term environmental and societal health. The essay crystallizes their learnings and proposes a long-term index that combines social, environmental, present, and future considerations.

Authors’ NoteBorn at the start of the twenty-first century, we are deeply concerned about the world that awaits us at its end. For too long, the consequences of climate change have been framed as eventualities. This has given those in power a comfort zone of inaction. But our generation does not have this same privilege; with each passing year we are being made vulnerable by unprecedented situations that have not been adequately prepared for or addressed. We had the right to inherit an uncontaminated world. Instead, we have inherited the responsibility to stave off the implications of climate change. Today we speak on behalf of a younger constituency who believes that immediate action is required to bring about the collaborations and transformations that will be necessary to do this. We have authored this paper as part of a larger effort to develop a resource that can help us understand the health of the human ecosystem relative to the environment.

IntroductionThe illusion that we can continue to defer action on global conservation and climate change mitigation efforts placate those who fail to employ foresight, and leaves the human condition of future generations unprotected by preparations that could be made in the present. It is likely that this inaction grows from the narrative that human civilization is prospering in a way that it has never before, from declining poverty rates to increasing literacy. These and other positive trends are triumphs to acknowledge, but their continuity is and will continue to be actively threatened by the implications of environmental destruction.

A diagram of Long Now co-founder Stewart Brand’s pace layer model.

A diagram of Long Now co-founder Stewart Brand’s pace layer model.How will human development fare as it comes under siege from climate change? And will there come a time when it — at odds with yet dependent upon the health of the environment — can no longer prosper? These questions are an imperative to developments that are well documented in the pace layer model. The pace layer model is a system of six components that descend in order of change-rates; fashion moves the fastest while nature moves the slowest. However, in light of environmental changes the behavior of nature is beginning to display characteristics of discontinuity and a fast rate of change that were once unique to the uppermost layers. We must question the assumption that our successes today will only be heightened tomorrow and make ourselves vulnerable to the reality that human progress is never inevitably linear.

So that we can better analyze how the conditions of both human progress and the environment will change in the future, we must step beyond forecasting and into the world of modeling. We are proposing the creation of a model that could seek to examine if and how the environmental changes wrought by our development could impede on our wellbeing. In order for such a model to be effective, we must first understand the historic and contemporary relationships we had and have with the environment.

Humans and the EnvironmentThe environment can impact civilization.Throughout history, there have been many regional examples of the environment’s impact on civilization. In the 12th and 13th centuries B.C.E, Bronze age civilizations such as the Mycenaean Greeks, Egyptians, and Assyrians either fully or partially collapsed due to a combination of large volcanic eruptions and powerful earthquakes, leading to large-scale migrations and societal chaos. More recently, a similar pattern of environmental events such as sea level rise, glacier retreat, and wildfires, are impacting populations across the globe. While past effects from isolated events were detrimental to human societies on a regional scale, current environmental catastrophes are impacting the entire planet, and can be conclusively attributed to the consequences of human actions.

Civilization can impact the environment.Human societies have had a tremendous impact on the environment around them. Historical examples include deforestation by the Mayan civilization in the Yucatán and aridization by the Anasazi culture in the U.S. Southwest. In modern times, similar types of habitat destruction continue and have been joined by a new anthropogenic impact: climate change. Recently, the United Nations released a statement detailing that “Today’s IPCC Working Group 1 report is a code red for humanity. The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable: greenhouse‑gas emissions from fossil-fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.” These impacts are linked to progress: climate change, habitat loss, pollution, and other forms of exploitation are the direct result of a worldwide increase in consumption and production of goods, foods, and products. Some of the world’s richest countries have the highest carbon footprints per capita, e.g. the US (15.52T), UAE (23.37T), and Kuwait (25.65T), while some of the poorest countries have the lowest carbon footprints per capita, e.g. the DR Congo (0.08T), Mozambique (0.21T), and Rwanda (0.12T). Despite these trends, we have observed that richer countries are viewed as the pinnacle of “progress.” Therefore, contemporary definitions of progress and its application in development are at least partially responsible for worsening environmental conditions.

The environment that we, Generation Z, find ourselves inheriting today has been deeply impacted by centuries of unfettered human activity. Most notably, post-industrial development and behaviors around the globe have had negative impacts on the natural environment, despite ostensibly improving human quality of life. Production demands insisting upon high growth metrics and the combination of industrial globalization and consumer demands have incentivized us to forgo environmental stewardship in lieu of “bottom line” results. These activities have led to the loss of nearly one third of global forests. Approximately one half of this loss occurred in the last century alone. The environment cannot sustain an economy that is focused solely on driving up production and consumption.

The cost of success.Because civilization degrades the environment, which in turn impacts society, civilization may eventually compromise its own existence. There is a reinforcing feedback loop: human development leads to environmental exploitation, which enables further development.

The cycle can be observed in the relationship between population and deforestation. As population increases, there is a greater demand for food and other resources. Harvesting these supplies takes priority over conserving the natural landscape, so that biodiverse, carbon dense forests are lost to the demands of a growing population. Since forests play an integral role in mitigating climate change and other environmental pressures, extensive deforestation threatens the natural balance of ecosystems. Thus we see that for the sake of obtaining resources, we actively engage in practices that although beneficial in the present, do, in the long run, threaten the viability of the world we inhabit.

This unsustainable cycle has, in fact, happened once before. In the 8th century, the Mayan civilization experienced huge population booms. For a period of time, they were able to sustain their growth with intensive land use that included practices such as slash-and-burn agriculture. After many years, however, the forests were decimated, the land was no longer productive, and large-scale droughts plagued the Yucatan peninsula. This resulted in societal unrest, rebellions, and substantial population reduction.

This negative reinforcing relationship does not only apply to population and deforestation. CO2 emissions and its relationship to production and the economy is another example. As production rates increase to provide goods to different countries, so too do consumption rates. The economic benefits that result from this process signify that the bigger and faster these feedback loops can become, the greater the materialistic reward. But the byproduct of this cycle is CO2 emissions, which tend to grow as the cycle accelerates. Since a continuous increase in CO2 emissions is creating an unstable environment, and an unstable environment can lead to an unstable civilization as discussed above, increased industrial output, or “progress,” could likely lead to civilizational decline.

In all examples, human development comes at the expense of environmental welfare. A conceptual representation of this idea is that as human progress goes up, environmental health goes down. Because such a relationship is unsustainable, it begs the question: at what point will human civilization start to suffer as a result of exploitative actions? Postulating that such could occur has Malthusian undertones as it presumes the depletion of a finite resource. But the reason why we must not be too quick to dismiss the argument is because we do not know if the technology of the future will be able to outpace environmental changes; we do not know if technological development will have positive impacts.

Quantifying ProgressAs discussed in the prior section, the environmental implications associated with climate change directly impact civilization. Although implications like regional temperatures are not all growing linearly, the correlation between them means that most will continue to get worse. Ultimately, the resulting conditions may be able to threaten the viability of human development. But to what degree?

Most of the models for human progress that exist today do not have the foresight needed to answer such a question. The Human Development Index uses gross domestic product (GDP), an indicator that is only viable for short term application and lacks the nuance needed to analyze the bottommost layers of society that are foundational to the challenges we face. The Social Progress Index and Environmental Performance Index both disregard economic indicators and uphold a standard for sustainability that coincides with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. While a sustainable focus will be paramount to global development, the methodologies of these indices are not structured to relay present actions to their long-term, future implications. Nor can they coincide our development with the health of the environment.

Instead of measuring our progress based solely around past and present data, a more conscious lens would be one that could also model how trends will age into the future. This would demonstrate if the successes we celebrate today can be sustained when faced by approaching environmental challenges.

A New Model for DevelopmentCurrent data reveals a dramatic decline in nature’s ability to absorb and stabilize the impact of human activity. We are proposing the creation of a predictive model with suggestions for inputs that measure the potential impacts our various current activities have and will have on the global ecosystem. These indicators could include metrics such as scientific literacy, rate of deforestation, socioeconomic inequality, and ozone depletion. We are leveraging the relationships proposed in the pace layer model to construct a dashboard or index that will provide meaningful outputs that, ultimately, can be evaluated and analyzed uniquely and in the aggregate. Additionally, our model could solicit data from predictive markets, which provide unique insights into human behavior and collective actions. Our ‘beverage-napkin’ sketch incorporating these elements and influencers might look something like this.

A sketch of our proposed predictive model.

A sketch of our proposed predictive model.To conclude, we have before us what may be our last opportunity to educate the broader population, and to begin reforms to systems that are collapsing the delicate balance that exists between the natural world and humankind. Opportunities abound to enact change, but educating the populace as to why these large scale changes are critical is essential not only to our collective wellbeing but ultimately, to our survival. This model will work to present clear and meaningful data that conveys the truth about our evolutionary gains and the stresses those gains impose upon the planet that supports us. How we choose to balance those forces will ultimately decide if we are able to prosper in the coming decades of the 21st century, or merely survive.

Lucienne Bacon is a senior year student at Avenues Online , a climate advocate, and nationally ranked dressage rider.

Lucas Kopinski is a senior year student at Avenues Online and a research fellow at Avenues Tiger Works.

Learn MoreThe following sources were used for informative purposes:

“Climate Change Raises Conflict Concerns” in UNESCO. The Environmental Performance Index.“Explainer: ‘Desertification’ and the Role of Climate Change” by Robert McSweeney in Carbon Brief. Human Development Reports , United Nations Development Programme.“Industrial Production – 100 Year Historical Chart” in MacroTrends. “Top CO2 Polluters and Highest per Capita” by Tejvan Pettinger in Economics Help. “The Short History of Global Living Conditions and Why It Matters That We Know It” by Max Roser in Our World in Data. Social Progress Imperative .“The World Has Lost One-Third of Its Forest, but an End of Deforestation Is Possible” by Hannah Ritchie in Our World in Data.

October 22, 2021

“Dune,” “Foundation,” and the Allure of Science Fiction that Thinks Long-Term

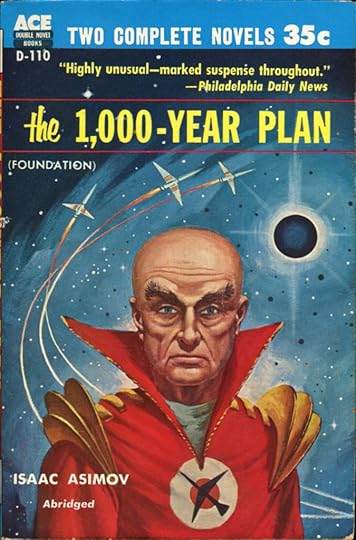

The first book of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series was also published as The 1,000-Year Plan — an indication of the series’ focus on long-term thinking. Cover design by Ed Valigursky Courtesy of Alittleblackegg/Flickr

The first book of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series was also published as The 1,000-Year Plan — an indication of the series’ focus on long-term thinking. Cover design by Ed Valigursky Courtesy of Alittleblackegg/FlickrPerusers of The Manual For Civilization, The Long Now Foundation’s library designed to sustain or rebuild civilization, are often surprised to find the category of Rigorous Science Fiction included alongside sections devoted to the Mechanics of Civilization, Long-term Thinking, and a Cultural Canon encompassing the most significant human literature. But these ventures into the imaginary tell us useful stories about potential futures.

Science fiction has long had a fascination with the extreme long-term. Two of the most important works of the genre’s infancy were Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men and H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine. Both books take their protagonists hundreds of thousands or millions of years into the future of humanity, reflecting turn of the twentieth century concerns about industrialization and modernization in the mirror of the far future.

In the modern canon of long-term thinking-focused science fiction, two works loom large: Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, eight books published in two bursts between 01942 and 01993; and Frank Herbert’s Dune cycle, six novels published sporadically from 01965 to 01985. Both series begin their first installments on the outskirts of decadent galactic empires in portrayals reminiscent of Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. As each series winds on, the protagonists of the story attempt to create a long-lasting civilization out of the chaos of an imperial crisis, crusaders against societal entropy.

Despite these similarities, the works have markedly different approaches to long-term thinking.

In Foundation, mathematician Hari Seldon devises a set of models that outline the future development of humanity. This set of models, referred to in the stories as the discipline of Psychohistory, would allow Seldon’s disciples to reduce the interregnum following the fall of the galactic empire from 30,000 years to a mere millennium. While Seldon’s plan is not perfect, the books still largely depict a triumph of long-term thinking. Asimov’s valiant scientists and scholars succeed in their goals of keeping galactic order in the end — though the series ends only 500 years into the millennium forecasted.

Frank Herbert’s Dune series unfolds on the scale of millennia, situating long-term thinking at the level of the individual god emperor. Courtesy of Maria Rantanen/Flickr

Frank Herbert’s Dune series unfolds on the scale of millennia, situating long-term thinking at the level of the individual god emperor. Courtesy of Maria Rantanen/FlickrDune instead adopts a more mythic conception of the long-term. While both works focus on secret societies with pan-galactic dreams, their means and ends could not be more different. Herbert’s order devoted to the future of the galaxy is a matriarchal sisterhood of witches, the Bene Gesserit, and the fruit of their work not a mathematical model but an individual — the Kwisatz Haderach, a kind of Übermensch with the ability to see the future. In Dune and its sequels, Paul Atreides and his son Leto II go from rulers of the strategically important desert world of Arrakis to absolute monarchs of the galaxy in order to ensure the continued survival of humanity. In the third book in the Dune series, Children of Dune, Leto II transforms into a half-human, half-sandworm monstrosity in order to reign for 3,500 years: a human embodiment of long-term thinking in the grimmest way imaginable.

Despite their differences, the works share another similarity: a recently released big budget adaptation. Both Foundation and Dune have long been seen as nigh-unadaptable due to their grand scale and ambition — Alejandro Jodorowsky and David Lynch’s attempts to capture Dune on film ended in varying degrees of failure, while Foundation’s gradual, intentionally anti-climactic style prevented Roland Emmerich from even beginning his take on the story. Yet Fall 02021 brings both Denis Villeneuve’s film adaptation of the first half of Dune and the first season of David S. Goyer and Josh Friedman’s take on Foundation.

The two adaptations have been met with different levels of excitement. Dune is one of the most anticipated theatrical events of a Fall movie season that features multiple Marvel blockbusters and a James Bond movie. It received an eight minute standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival, and is expected to make hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office. Foundation arrived with considerably less fanfare; its launch on Apple TV’s streaming service drew lukewarmly positive reviews and not much in the way of broader pop cultural impact.

The differences in reception between the two adaptations can be attributed to a variety of factors: the density of stars on Dune’s cast, Villeneuve’s seemingly limitless budget for sci-fi spectacle, the fact that Foundation is limited to a streaming service rather than a movie screen. Even the original works have their stylistic differences. Dune is a fairly conventional tale of courtly intrigue that happens to be set in space, while Foundation is a series of loosely connected novellas about bureaucrats and traders.

Or perhaps it is the difference between the two works’ philosophical outlooks. In their long views, Asimov and Herbert took diametrically opposed stances — the trust-the-plan humanistic optimism of Foundation in one corner, the esoteric pessimism of Dune in the other. Since their publications, both works have influenced a wide variety of thinkers: Foundation motivated Paul Krugman to begin his study in Economics and inspired parts of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, while Dune has inspired everyone from astronomers to environmental scientists to Elon Musk. The books show up in The Manual for Civilization as well — both of them on Long Now Co-founder Stewart Brand’s list.

In a moment of broader cultural gloominess, Dune’s perspective may resonate more with the current movie-going public. Its themes of long-term ecological destruction, terraforming, and the specter of religious extremism seem in many ways ripped out of the headlines, while Asimov’s technocratic belief in scholarly wisdom as a shining light may be less in vogue. Ultimately, though, the core appeal of these works is not in how each matches with the fashion of today, but in how they look forward through thousands of years of human futures, keeping our imagination of long-term thinking alive.

Learn More:Read Stewart Brand’s list for The Manual for CivilizationRead Long Now Fellow Roman Krznaric’s list of the best books for long-term thinking, which includes a shout-out to Foundation.Watch Annalee Newitz’s 02018 Long Now Talk for another perspective on how science fiction can help us think about the future.Watch Neal Stephenson’s 02008 Long Now Talk about his novel Anathem, another science fiction novel about long-term thinking (and a long-term Clock)

September 30, 2021

The Next 25(0[0]) Years of the Internet Archive

Long Now’s Website, as reimagined by the Internet Archive’s Wayforward Machine

Long Now’s Website, as reimagined by the Internet Archive’s Wayforward MachineFor the past 25 years, the Internet Archive has embraced a bold vision of “Universal Access to All Knowledge.” Founded in 01996, its collection is in a class of its own: 28 million texts and books, 14 million audio recordings (including almost every Grateful Dead live show), over half a million software programs, and more. The Archive’s crown jewel, though, is its archive of the web itself: over 600 billion web pages saved, amounting to more than 70 petabytes (which is 70 * 10^15 bytes, for those unfamiliar with such scale) of data stored in total. Using the Archive’s Wayback Machine, you can view the history of the web from 01996 to the present — take a look at the first recorded iteration of Long Now’s website for a window back into the internet of the late 01990s, for example.

Internet Archive Founder Brewster Kahle in conversation with Long Now Co-Founder Stewart Brand at Kahle’s 02011 Long Now Talk

Internet Archive Founder Brewster Kahle in conversation with Long Now Co-Founder Stewart Brand at Kahle’s 02011 Long Now TalkThe Internet Archive’s goal is not simply to collect this information, but to preserve it for the long-term. Since its inception, the team behind the Internet Archive has been deeply aware of the risks and potentials for loss of information — in his Long Now Talk on the Internet Archive, founder Brewster Kahle noted that the Library of Alexandria is best known for burning down. In creating backups of the Archive around the world, the Internet Archive has committed to fighting back against the tendency of individual governments and other forces to destroy information. Most of all, according to Kahle, they’ve committed to a policy of “love”: without communal care and attention, these records will disappear.

For its 25th anniversary, the Internet Archive has decided to not just celebrate what it has achieved already, but to warn against what could happen in the next 25 years of the internet. Its Wayforward Machine offers an imagined vision of a dystopian future internet, with access to knowledge hemmed in by corporate and governmental barriers. It’s exactly the future that the Internet Archive is working against with every page archived.

Of course, the internet (and the Internet Archive) will likely last beyond 02046. What does the further future of Universal Access to All Knowledge look like? As we stretch out beyond the next 25 years, onward to 02271 and even to 04521, the risks and opportunities involved with the Archive’s mission of massive, open archival storage grow exponentially. It is (comparatively) easy to anticipate the dangers of the next few decades; it is harder to predict the challenges lurking under deeper Pace Layers. 250 years ago, the Library of Congress had not been established; 2500 years ago, the Library of Alexandria had not been established. Averting a Digital Dark Age is a task that will require generations of diligent, inventive caretakership. The Internet Archive will be there to care for it as long as access to knowledge is at risk.

Learn More:

Check out the Internet Archive’s full IA2046 site, which includes a timeline of a dystopian future of the web and a variety of resources related to preventing it.Read our coverage of the Digital Dark Age From 01998: Read a recap of our Time & Bits conference, which focused on the issue of digital continuity. Perhaps ironically, some of the links no longer work.For another possible future of the internet in 02046, see Kevin Kelly’s 02016 Talk on the Next 30 Digital YearsFor another view on knowledge preservation, see Hugh Howey’s 02015 Talk at the Interval about building The Library That Lasts

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers