Stewart Brand's Blog, page 66

September 11, 2013

Optimism in the Anthropocene

On sci-fi and futurism blog io9, editor Annalee Newitz made the case recently for what she calls geological optimism:

My hope for the future comes from geology, and a belief that one day we will invent machines that are environmental rather than technological.

Newitz argues that thinking about change and growth in primarily technological terms is bound to leave us blinkered and disappointed. In the same vein, Professor of Economics Jonathan Dawson hopes for a similarly expanded awareness to reshape economic thought in a column for The Guardian:

Ecology offers the insight that the economy is best understood as a complex adaptive system, more a garden to be lovingly observed and tended than a machine to be regulated by mathematically calculable formulae.

Technology is but one epiphenomenon of the natural world and it sits nested within larger, slower societal, biological and geological processes. In the concept of pace layering, inspired by the architectural idea of shearing layers, technology is primarily a commerce and infrastructure level phenomenon, but increasingly has effects on even the deepest, slowest layers.

It is largely through technology that humans have (more or less by accident) become drivers of the planetary system. As we develop agency within the deeper, slower layers of our world’s processes, we must better understand those systems and better incorporate their operating principles into our own self-governance, else we’ll drive into a ditch.

The flaws in techno-optimism and classical economic thinking Newitz and Dawson decry represent the clumsy influence of the commerce and infrastructure layers on the nature and culture layers. Both authors propose that we instead allow our increasingly refined understandings of nature and culture to inform decisions in the faster layers.

A real-world example can be seen in National Geographic’s recent cover story on sea-level rise. Surveying how communities around the world are adapting to and preparing for redefined coastlines, author Tim Folger describes a Dutch creation known as the zandmotor. Where sea-level rise has lead to beach erosion, flooding is a danger and traditional renourishment methods are expensive:

The typical solution would be to dredge sand offshore and dump it directly on the eroding beaches—and then repeat the process year after year as the sand washes away. Mulder and his colleagues recommended that the provincial government try a different strategy: a single gargantuan dredging operation to create the sandy peninsula we’re walking on—a hook-shaped stretch of beach the size of 250 football fields. If the scheme works, over the next 20 years the wind, waves, and tides will spread its sand 15 miles up and down the coast. The combination of wind, waves, tides, and sand is the zandmotor.

In 02009, author and forecaster Karl Schroeder sketched a near-future scenario (already both dated and prescient) that also serves to illustrate a type of geological optimism. He calls his scenario “re-wilding” and in one example describes a wetland that naturally filters the water for a city. Sufficiently monitored and understood, its value to the human economy – and individual consumers – can be precisely calculated and billed. Imaging this possibility where today we’d more likely build a man-made filtration plant, he explains, ”We’ve introduced the idea of negotiating with a self-willed world.”

While next century’s historians may call our time the Information Age, the next millennium’s historians will likely be more interested in the dawn the of Anthropocene epoch. As a cynical saying goes, “Employees tend to rise to their level of incompetence.” And as the scale of humanity’s influence on the natural world has expanded, it’s hard not to worry that we’re promoting ourselves beyond our capabilities. But the zandmotor and the possibility of re-wilding can be sources of hope, signs that our understandings of different pace layers are increasing and increasingly allowing us to grow into our role, and evidence that geological optimism and the Anthropocene aren’t mutually exclusive.

September 9, 2013

The Oldest Petroglyphs in the American West

The story of the oldest Americans is largely unknown to us; the first people to arrive on the North American continent didn’t leave behind any material clues for later generations to find. But a recent discovery in Nevada may now offer us a little glimpse into their world. In a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, a team of researchers reveals that a series of petroglyphs, carved into boulders near Pyramid Lake, are even older than previously suspected – and might be attributed to the first people to set foot in the American West.

Unlike those ancient Americans, weather patterns do leave their mark on the world around them – and this allowed paleoclimatologist Larry Benson to determine that the images are about 10,000, or about 14,000, years old. The petroglyphs are carved into what Benson knew to be a lakebed, and must therefore have been created during a dry period. Chemical testing of samples from the site revealed that such a dry period occurred between 14,800 and 13,200 years ago, and again between 11,300 and 10,500 years ago. Whichever dating turns out to be the right one, these are easily the oldest petroglyphs that have been found on the North American continent, and will inform what we know about the first people to cross the Bering Strait.

The images are composed of abstract swirling and geometrical patterns. The researchers have suggested that the carvings may depict natural phenomena, such as leaves, clouds, or even the Milky Way. But without other evidence of culture from this period, it will be difficult to determine what exactly the etchings represent – or who created them.

“We have no idea what they mean,” Benson said of the Winnemucca Lake petroglyphs. “But I think they are absolutely beautiful symbols. Some look like multiple connected sets of diamonds, and some look like trees, or veins in a leaf. There are few petroglyphs in the American Southwest that are as deeply carved as these, and few that have the same sense of size.”

September 6, 2013

The Majestic Plastic Bag

The Majestic Plastic Bag from Heal the Bay on Vimeo.

Heal the Bay, a nonprofit environmental organization working to improve watersheds and coastal areas of Southern California, made this short film that tracks the ‘migration’ of a plastic bag from the grocery store to the ocean. The film is narrated by Jeremy Irons, and was featured as a Long Short in our series of short films that convey long-term thinking. It was screened at our May 02012 SALT seminar with Susan Freinkel, Eternal Plastic: A Toxic Love Story.

September 5, 2013

Peter Schwartz Seminar Primer

Tuesday September 17, 02013 at SFJAZZ Center, San Francisco

Peter Schwartz likes taking a long view. He’s a founding board member of The Long Now Foundation and in his career as a scenario planner he’s at the forefront of futurist thought, known for his book, The Art of the Long View, a canonical text of thinking long-term, and for founding the Global Business Network, a strategic planning consulting firm. In a Long Now SALT in 02008 he debated historian Niall Ferguson about the potential for human progress, arguing strongly for the importance of optimism. “Optimism” he concluded, “lets you imagine how you can overcome problems, and those possibilities motivate change.”

Schwartz’s long view has, in the last few years, begun to extend well off-planet, past Mars and the asteroid belt, and even beyond the Oort Cloud – in a Long Now event in 02010, he asked NASA Ames Research Center Director, Pete Worden about the possibility of starships that might take humans out of our own solar system. In response, Worden announced that NASA and DARPA had just begun a program to fund realistic, scientific research into the prospects of what they were calling 100-year starships:

Long Conversation – Pete Worden Announces 100-Year Starship from The Long Now Foundation on Vimeo.

Since then, thinking and planning for interstellar travel has snowballed. The inaugural 100 Year Starship Symposium was held in 02011, with a second in 02012 and the third later this month. Each event has gathered dozens of papers seeking to collectively establish a rough sketch of the technological, physical and social engineering interstellar travel will require.

Starship Century is an anthology just released (and on sale at the upcoming lecture) that features writing by Peter Schwartz, Stephen Hawking, Martin Rees, Neal Stephenson and many others on the existential necessity, the voluminous challenges, and the unprecedented promise of travelling to the stars.

Peter Schwartz has applied a bit of his world-renowned scenario planning to the possibility of starships and he brings our interstellar future into view on September 17th at SFJAZZ Center. You can reserve tickets, get directions and sign up for the podcast on the Seminar page.

September 3, 2013

Three Major Installations (and an impending opening?) by James Turrell

Artist James Turrell, though generally somewhat elusive and inclined towards private commissions, has had a big summer, as reported by the New York Times in June. Major installations by Turrell have been featured in New York, Houston and Los Angeles. The first two end this month, while the latter runs through April of 02014.

His work focuses on light and perception and the full experience often requires a viewer to spend more than a passing glance. That’s because it can take the human eye up to 45 minutes to fully adjust to a dark room and many of Turrell’s installations make use of such subtle light effects that patience is required to even see what he’s done. The large scale and precise requirements of his work make this summer’s nationwide availability of it an unprecedented opportunity.

Turrell’s immersive installations create spaces not unlike the scenes in The Matrix where characters discuss their world’s central illusion – except in place of Neo’s and Morpheus’s colorless void, Turrell offers a world of color.

In other pieces, he creates Skyspaces – open roofed rooms with carefully calibrated ceilings and lights that seem to bring the sky down, to give it texture and to make it appear material.

He’s also known for the mythic Roden Crater, an extinct volcano he bought in 01977. Since then, work at the site has been aimed at creating a naked-eye observatory using principles of light and perception similar to his more accessible installations, but cosmic in scale. An ever more prevalent element of the mythos of the project is the question of when it will be done. Few have seen it as it’s come together over the decades, but the author of Turrell’s recent New York Times profile was able to explore and discuss Roden Crater in depth:

One by one, we walked up the tunnel. It was 854 feet long and 12 feet in diameter, with blue-black interior walls and ribs protruding every four feet. At the top, a great white circle of light beamed toward us. Or so it seemed. As we drew closer, the color changed from white to blue, and the shape began to shift, elongating from a circle to an oval and rising overhead, until it was clear that what had seemed to be a round opening at the far end of the tunnel was in fact an elliptical Skyspace in a large viewing room. A long, narrow staircase made of bronze ascended through it.

We climbed onto the top of the crater and stepped into the sun. Once again we were surrounded by a Martian landscape of crushed red stone. A cold wind blew across the caldera, and we lay down to view the sky, the clouds streaking overhead as the heavens vaulted.

Dusk was coming. We got up and followed a narrow ramp into another Skyspace. It was round, with a narrow bench around the perimeter. Turrell calls it “Crater’s Eye.” We took seats on the bench and stared through the opening in silence. The color of the sky was deepening. It was rich with blue and darkness. It seemed to hover on the ceiling close enough to touch. No one spoke for 30 minutes. I glanced over at Turrell. His hands were folded in his lap, his eyes smiling at the sky. Whatever else the crater had become for him — a job, a dream, an office, a persistent reminder of his own mortality — it was clear that the Skyspace still had the power to lift him up from earth.

Turrell may, it seems, reward patience like few artists can.

August 29, 2013

Daniel Kahneman Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Thinking Fast and Slow

Tuesday August 13, 02013 – San Francisco

Video is up on the Kahneman Seminar page for Members.

*********************

Audio is up on the Kahneman Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

On taking thought – a summary by Stewart Brand

Before a packed house, Kahneman began with the distinction between what he calls mental “System 1”—fast thinking, intuition—and “System 2”—slow thinking, careful consideration and calculation. System 1 operates on the illusory principle: What you see is all there is. System 2 studies the larger context. System 1 works fast (hence its value) but it is unaware of its own process. Conclusions come to you without any awareness of how they were arrived at. System 2 processes are self-aware, but they are lazy and would prefer to defer to the quick convenience of System 1.

“Fast thinking,” he said, “is something that happens to you. Slow thinking is something you do.“

System 2 is effortful The self-control it requires can be depleted by fatigue. Research has shown that when you are tired it is much harder to perform a task such as keeping seven digits in mind while solving a mental puzzle, and you are more impulsive (I’ll have some chocolate cake!). You are readier to default to System 1.

“The world in System 1 is a lot simpler than the real world,” Kahneman said, because it craves coherence and builds simplistic stories. “If you don’t like Obama’s politics, you think he has big ears.” System 1 is blind to statistics and focuses on the particular rather than the general: “People are more afraid of dying in a terrorist incident than they are of dying.”

When faced with a hard question such as, “Should I hire this person?” we convert it to an easier question: “Do I like this person?“ (System 1 is good at predicting likeability.) The suggested answer pops up, we endorse it, and believe it. And we wind up with someone affable and wrong for the job.

The needed trick is knowing when to distrust the easy first answer and bear down on serious research and thought. Organizations can manage that trick by requiring certain protocols and checklists that invoke System 2 analysis. Individual professionals (athletes, firefighters, pilots) often use training to make their System 1 intuition extremely expert in acting swiftly on a wider range of signals and options than amateurs can handle. It is a case of System 2 training System 1 to act in restricted circumstances with System 2 thoroughness at System 1 speed. It takes years to do well.

Technology can help, the way a heads-up display makes it possible for pilots to notice what is most important for them to act on even in an emergency. The Web can help, Kahneman suggested in answer to a question from the audience, because it makes research so easy. “Looking things up exposes you to alternatives. This is a profound change.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

August 28, 2013

Silent Evolution

Silent Evolution by Jennifer Piazza was screened at Timothy Ferris’ September 02011 SALT talk, “Accelerated Learning in Accelerated Times“. It features the art of Jason deCaires Taylor.

Taylor’s installation work is not found in galleries or typical sculpture gardens. Instead he places sculptures on the ocean floor, in locations where they slowly and silently accrue the trappings of a coral reef. Silent Evolution is an installation off the coast of Mexico.

Long Now chooses short films that convey long-term thinking to proceed many of our Seminars, a series we call Long Shorts.

August 23, 2013

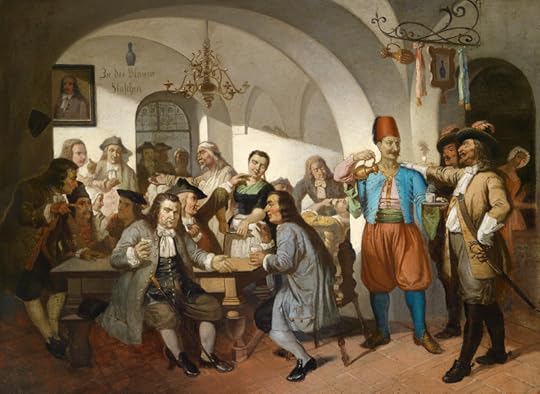

Seminars, Salons and the Long Tradition of Raising Cups in Conversation

November 02013 will mark the 10th anniversary of the first of Long Now’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking. One of our founding board members, Brian Eno, gave that first talk which was entitled “The Long Now” and featured an overview of the Long Now Foundation (already 7 years old at that time) and the events that led to its founding.

From the beginning, these talks have inspired conversation – in fact each Seminar ends with an onstage conversation between the speaker and Stewart Brand, including questions submitted by our audience. We have used this format since the very first of our 143 Seminars (and counting!) because our goal is to get you talking about Long-term thinking, not just hearing about it from the lectern.

After we moved to Fort Mason Center we sometimes used our Museum & Store space for post-Seminar receptions. This allowed Long Now Members and other attendees to keep the conversation going after a thought-provoking seminar. On those nights, scores of people filled the space between our 10,000 Year Clock prototypes and Rosetta Project displays, standing and drinking wine, animatedly discussing ideas that look forward centuries and millennia.

At those receptions and a series of other small lectures and events we held in the Museum space, the idea for The Long Now Salon was born.

As we contemplated how to inspire the type of thoughtful interactions we hope will fill our new public space, we kept coming back to two historical precedents that developed in conjunction with the European Enlightenment: English coffeehouses and French salons. In their day, both developments represented new, more inclusive realms of public discourse. The heady mixture of reason’s ascendancy and surging coffee imports made for a middle-class intellectual blossoming.

The salons of the French Enlightenment don’t generally refer to specific places or venues, but rather events held in a host’s home. In contrast to the monarchy’s court society, where artists or poets would perform for their patrons and other powerful figures, salons allowed for a more mixed and egalitarian atmosphere where poetry, art, politics or philosophy could be discussed among a wider range of curious citizens. Women often organized and participated in the events, as did artists and intellectuals who would otherwise be unlikely to gain access to aristocratic circles. In this way, ideas were disseminated and exchanged in a newly diverse and networked realm that lay somewhere between the private conversations of individuals and the formal political bureaucracy: the public sphere.

Meanwhile, in England a similar process was happening as coffeehouses became a popular alternative to pubs for socializing. One of the first coffeehouses was established in Oxford, leading to a clientele that consisted of many academics interested in stimulating (and stimulated) intellectual conversation. Visitors could sip coffee or tea and often discussed news and politics. But, because the space was open to the public, as opposed to the university’s chambers, the conversations could include many who weren’t among the cultural elite (though, unlike in the French salons, this openness did not generally extend to women). Many coffeehouses published their own local newspapers, giving rise to a thriving print industry and many posted house rules meant specifically to foster egalitarianism (amongst men), civility and conversation. Like the salons, they supported the development of a thriving community with curious and relatively diverse perspectives where issues of the day could be collectively and publicly discussed.

In both of those precedents the Host plays an important role. And as with our lectures and other events, we feel it’s important to create an atmosphere that both inspires conversation and helps develop a sense of community around these important topics. So the design for the physical space, programming, and menu of the Salon began to take shape with that in mind.

With tea, coffee, wine, beer, and craft cocktails to get the ideas flowing; an inviting atmosphere that attracts all kinds of curious thinkers; prototypes of the 10,000-year Clock and our Manual for Civilization to frame our interests in long-term thinking; and regular public programs like the SALT talks but smaller and more intimate to bring many minds together – we envision the Salon space will tap into some of the same enlightening characteristics of the salons and coffeehouses of centuries past.

We hope you’ll help us build it and we’d love to see you there when it’s done.

August 21, 2013

Harmonic Spheres and the Music of the Cosmos

In the 6th century BC, Pythagoras developed the science of harmonics. Legend has it that he was inspired by the sounds emanating from a blacksmith’s shop; producing experimental music with hammers and anvils, Pythagoras realized that the relationship between different musical notes can be expressed in the form of simple mathematical ratios.

Pythagoras saw in this a fundamental theory of the universe, and redefined the world – from the motion of celestial bodies to the emotional fluctuations in a human body – as iterations of a kind of cosmic music. More than a millennium later, Johannes Kepler interpreted this musica universalis as proof of Divine splendor, and devoted his career to a description of the geometric and harmonic order of our solar system.

Efforts to chart this celestial harmony can produce strikingly aesthetic images. Kepler’s sketches proved as much in his publications – as does this work by software developer Howard Arrington. Arrington used his own Ensign software to visualize the relationship between pairs of planets, producing a series of intriguing geometric mosaics. Better yet, he shares the program with which he created his images, so that you, too, can capture the music of the cosmos.

August 20, 2013

Daniel Kahneman Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Thinking Fast and Slow

Tuesday August 13, 02013 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Kahneman Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

On taking thought – a summary by Stewart Brand

Before a packed house, Kahneman began with the distinction between what he calls mental “System 1”—fast thinking, intuition—and “System 2”—slow thinking, careful consideration and calculation. System 1 operates on the illusory principle: What you see is all there is. System 2 studies the larger context. System 1 works fast (hence its value) but it is unaware of its own process. Conclusions come to you without any awareness of how they were arrived at. System 2 processes are self-aware, but they are lazy and would prefer to defer to the quick convenience of System 1.

“Fast thinking,” he said, “is something that happens to you. Slow thinking is something you do.“

System 2 is effortful The self-control it requires can be depleted by fatigue. Research has shown that when you are tired it is much harder to perform a task such as keeping seven digits in mind while solving a mental puzzle, and you are more impulsive (I’ll have some chocolate cake!). You are readier to default to System 1.

“The world in System 1 is a lot simpler than the real world,” Kahneman said, because it craves coherence and builds simplistic stories. “If you don’t like Obama’s politics, you think he has big ears.” System 1 is blind to statistics and focuses on the particular rather than the general: “People are more afraid of dying in a terrorist incident than they are of dying.”

When faced with a hard question such as, “Should I hire this person?” we convert it to an easier question: “Do I like this person?“ (System 1 is good at predicting likeability.) The suggested answer pops up, we endorse it, and believe it. And we wind up with someone affable and wrong for the job.

The needed trick is knowing when to distrust the easy first answer and bear down on serious research and thought. Organizations can manage that trick by requiring certain protocols and checklists that invoke System 2 analysis. Individual professionals (athletes, firefighters, pilots) often use training to make their System 1 intuition extremely expert in acting swiftly on a wider range of signals and options than amateurs can handle. It is a case of System 2 training System 1 to act in restricted circumstances with System 2 thoroughness at System 1 speed. It takes years to do well.

Technology can help, the way a heads-up display makes it possible for pilots to notice what is most important for them to act on even in an emergency. The Web can help, Kahneman suggested in answer to a question from the audience, because it makes research so easy. “Looking things up exposes you to alternatives. This is a profound change.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers