Stewart Brand's Blog, page 64

October 21, 2013

Adam Steltzner Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

Beyond Mars, Earth

Tuesday October 15, 02013 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Steltzner Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Mighty daring on Mars

- a summary by Stewart Brand

Engineer Steltzner took his rapt audience striding with him through the wrong solutions for landing a one-ton rover on Mars that his team worked through a decade ago. Previous rovers had weighed 50 pounds, 385 pounds. This traveling “Mars Science Laboratory” would weigh 1,984 pounds. The old airbag trick wouldn’t work this time, nor would a palette, or legs.

After exhausting everything that looked reasonable but could not work, the team settled on a mini-rocket “sky crane” approach that might be able to work, but there was nothing reasonable-looking about it. Selling the concept, Steltzner invoked arguments such as: “Great works and great follies may be indistinguishable at the outset,” while reminding himself that “Sometimes what looks crazy is crazy.” To make things worse, the idea could not be tested on Earth, because our atmosphere and gravity situation is so different from Mars, “and simulations only answer things you know to worry about.”

Furthermore, the landing had to occur within a tiny target ellipse only 4 by 12 miles in the Gale Crater at the base of Mount Sharp, which stands 15,000 feet about the crater floor. To “kiss the Martian surface” at that spot, the landing system had to go through multiple stages (the “seven minutes of terror”) totally on its own, decelerating violently from 10,000 miles per hour to a gentle 0 mph without a single flaw at any stage. On August 6, 2012, with the whole world watching, the system performed perfectly, and Steltzner’s team at JPL exploded with high-fives and tears on the world’s screens.

After showing the video, Steltzner asked, “Why do it, why spend the $2.5 billion the mission cost?” One eternal question about Mars is whether life is there, or was there. This rover has already determined that Mars once had sufficient amounts of the right kind of water that life could have managed there. “It would have been something bacterial, pond-scummy.” He is now at work on a conjectural series of three missions to bring samples of Martian material back to Earth. The first mission would collect and cache the samples; the second would launch the cache to Mars orbit; the third would return it to Earth. Later projects should explore the ice-covered ocean of Jupiter’s moon Europa and the methane lakes of Saturn’s moon Titan.

“With this kind of exploration,“ Steltzner said, “we’re really asking questions about ourselves. How great is our reach? How grand are we? Exploration of this kind is not practical, but it is essential.” He quoted Theodore Roosevelt: “Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs even though checkered by failure, than to rank with those timid spirits who neither enjoy nor suffer much because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.”

Steltzner reminded the audience of the relative inhospitability of Mars and the intense inhospitability of space. “Outside of the magnetic field of this planet that shelters us from the streaming radiation of the Sun, it’s a really nasty place. It’s inconceivably cold or indescribably hot, bathed in radiation.” To contemplate terraforming Mars or building colonies in space, he said, makes solving the problems here on Earth of maintaining this planet’s exquisite balance for life seem so obvious and doable.

In the harsh lifelessness of space we discover how precious is life on Earth.

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

October 18, 2013

Your DNA: Library or Thunderdome?

Systems biologist Michael White, writing for Pacific Standard, dismisses the narrative that our genetic material is a “highly sophisticated, finely tuned data storage and processing device.” Instead, he says, it is an apocalyptic wasteland “littered with the rubble of ancient and ongoing battles with hordes of viruses, clone armies of genetic parasites, and zombie genes that should be dead but aren’t.” Arguing towards an ecology of the eukaryote genome, he likens it to an ecosystem full of communities that have grown, preserved, interacted and competed with each other in a complex system of relationships:

The major players in our genomic ecosystem are DNA parasites called transposable elements, named for their ability to move around the genome and make copies of themselves. Transposable elements, which make up at least half our genome, are “selfish” genetic elements that exist because they have a strategy to get passed on to the next generation without necessarily contributing any useful function to the organism. Other denizens of our DNA include Human Endogenous Retroviruses (HERVS, eight percent of our genome), viruses that took up permanent residence in the egg or sperm cell of one of our distant ancestors, and zombie “pseudogenes,” functional genes that were killed by some genetic mishap but still have an influence on their surrounding genes.

According to the PLOS Genetics study White references, about 50% of the human genome sequence is referred to as “dark matter” because of its unknown purpose or origin. The study demonstrates that approximately half of this dark matter is made up of repetitive sequences, “which are most likely dominated by transposable elements.”

Since transposable elements (TEs) are a considerable component of our biology, better understanding them is a fundamental issue in genetics. How do they help and how do they harm? White says TEs have contributed to building new links between genes. But he also states that this genetic innovation results in uncontrolled variability and unwanted mutations, leading to certain human diseases. The exact role TEs play in our genome will take a long time to unravel, but the picture they’re already beginning to paint depicts a less-than-harmonious path to our present selves.

The idea that your genome is an ecosystem populated with species that pursue their own self-interest may make you wonder: Who am I, really? Unlike the parasites that you pick up when you drink the water in a place where you shouldn’t, transposable elements and endogenous viruses aren’t really foreign invaders; they are your DNA, and they have been part of our genetic identity for longer than we have existed as a species.

(The image above was painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.)

October 17, 2013

Rosetta and PanLex Projects at Exploratorium Market Days 10/19/13

This Saturday October the 19th, Rosetta and PanLex Project staff will be at the Exploratorium’s final Market Days event of this year. The Exploratorium has been holding these free, outdoor events in the spirit of “exchanging fresh ideas on local phenomena.” Saturday’s theme is Heirlooms and Rosetta and PanLex will showcase our planet’s diverse linguistic stock.

Come to the Rosetta / PanLex Project booth where you can:

Learn about the thousands of languages spoken around the world, why many of them are endangered, and why this is important for everybody.

Learn how you can make and archive language recordings that document the languages used in your family, classroom and community.

Use the PanLex tattoo generator to make a temporary tattoo using words from thousands of languages around the world.

See a real Rosetta Disk – an archive of thousands of the world’s languages that read with a microscope, and can hold in the palm of your hand.

The event runs from 11:00am to 3:00pm at the Exploratorium’s new location at Pier 15.

October 16, 2013

Dissident Futures at YBCA

On October 17th, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts opens their new exhibition, Dissident Futures which will explore how we think about possible futures through a variety of media, with a thematic focus on utopian, speculative, and pragmatic concepts.

A range of programs will be presented in conjunction with the exhibit, in collaboration with Long Now and other Bay Area organizations.

Dissident Futures presents art that investigates possible alternative futures, particularly those that question or overturn conventional notions of innovation, such as existing power, economic and technological structures.

Long Now has partnered with YBCA on three events throughout the exhibition:

Opening Night Party

Friday October 18th, 8:00pm to 10:00pm

Free for Long Now Members (check your email for promo code!)

Project Nunway

Saturday November 2nd, 7:00pm

with Long Bets table (make predictions without the $50 Prediction fee)

Dissident Futures Art and Ideas Festival

Saturday November 23rd, 1:00pm to 10:00pm

Long Now staff present on The Manual for Civilization at 2:00pm, Free with RSVP

October 14, 2013

No Apocalypse Necessary

Writing for Aeon Magazine, Colin Dickey, visited the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and discusses the apocalyptic rhetoric often associated with the project. He points out that apocalyptic thinking, while sometimes an effective motivator, can be a barrier to long-term thinking.

This obsession with impending disaster suggests that we see nature on a particularly human, individual scale. When we think of environmental damage and the human impact on the ecosystem, we think almost exclusively in the short term. The millennium, be it religious or environmental, is always coming the day after tomorrow.

Exploring the surrounding environment, he marvels at how little human history has transpired in this remote place and yet how well what has happened there has been preserved. Today’s apocalyptic narratives put nature in the role of a vengeful god, but Dickey finds hints of salvation in Svalbard’s landscape. The seed vault, he points out, isn’t primarily a reaction to imminent disaster, but rather a hedge against slow-moving trends threatening crop-diversity and it utilizes the naturally cryogenic Arctic to its advantage.

Sometimes what seems like a panicked gasp for breath is something else entirely. The lessons of Svalbard are more complex than the simple, immediate apocalypse intimated by the hype surrounding the seed vault…

… A proper relationship to nature must involve a sense of stewardship, to be sure, and a willingness to work for a better tomorrow. But it might also do well to be stripped of a histrionic sense of perpetual catastrophe. Places such as Svalbard can help us to think on a much longer, deeper scale — one in which we are peripheral characters in a drama taking aeons to unfold.

Read Deep Chill, by Colin Dickey

October 10, 2013

Long Now Salon Update: Time on the Menu

Photo by Catherine Borgeson

Progress on the Long Now Salon continues. We have told you a lot about the design and building of the space (most recently about our cardboard prototyping night) and the library we are building for it. But while renovating the physical space is an important aspect of opening this new venue, there’s a lot more to launching a public space that celebrates long-term thinking. And so we are hard at work planning things like drink menus and programming that will really bring our beautiful space to life.

We think a lot about beverages and time. The histories of civilization and distillation are synchronous and intertwined across many cultures. There are so many fascinating stories associated with spirits through the ages. One example is a liqueur whose 400-year-old, 130-ingredient recipe is kept secret by French monks.

At the turn of the 17th Century the alchemical formula of this “elixir of long life” was named after the Chartreuse mountains and the Grande Chartreuse monastery where it is still made today. The spirit’s distinctive shade of green is the origin of the color chartreuse (not the other way around). It’s a safe bet you’ll find Chartreuse in the Salon when we open next year.

Alcohol will generally be reserved for the evenings at the Salon, so we’ll have plenty of thought-provoking liquids for our daylight visitors as well. Our partners at Samovar Tea Lounge helped us find a rare Pu-erh tea for Salon donors, and we’ll have a variety of other non-alcoholic beverages including local artisan coffee for those who visit while the sun’s out.

Photo from Wikipedia

A big announcement about the Salon is coming soon and there’s more news to share about our drinks menu. And time. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile, a video we’ve posted before, but it’s a must-watch if you haven’t seen it. Lance Winters of our partners St. George Spirits discusses the relation of time and distillation.

October 9, 2013

Paul Sabin on the Gamble over Earth’s Future

In 1980, a bet was made between a Malthusian ecologist and a Cornucopian economist – between optimism and pessimism – about the fate of humanity and planet Earth. The wager concerned fluctuations in the market prices for several crude metals. If prices rose over the next decade, civilization must be facing scarcity and thus inevitable doom; falling prices, on the other hand, would signal abundance, ingenuity, and human prosperity. In 1990, optimism won. (A longer-term bet, however, would have turned out differently.)

Last month, Yale historian Paul Sabin published a book in which he revisits this iconic bet. Delving into the philosophical disagreements between doomsday-saying environmentalists and optimistic believers in the adaptive powers of human innovation, the book ultimately asks: how should we measure global prosperity, and what will spur us to act on a changing environment?

While the (rising) price of essential commodities can be a powerful motivator for action, Sabin writes, some important indices of civilizational well-being may not be reflected in the behavior of the free markets (think, for example, of the impact of carbon dioxide emissions, which currently carry no financial burden). Nevertheless, doomsday-warnings about the impact of environmental destruction do not seem to be much better at prompting productive responses to our evolving world. Advocating a middle ground between these two entrenched perspectives, Sabin ultimately argues that the future of our planet is best served by actions and decisions that are driven by social values – and a long-term perspective:

“I think that environmentalists would find a more solid foundation to advocate action if they made their case based on social values, rather than apocalyptic fear. What kind of world do we want to live in? Humans might survive, and even prosper economically, in a warmer and more populated world. But are the risks associated with climate change worth taking? (The answer, I think, is clearly “no.”) Do we want to live on a more biologically impoverished, albeit economically productive, planet? These are profound social questions that, I might point out (as a historian), cannot be answered by economics or biology alone but rather depend on the humanities and can only be resolved through politics.”

The Bet: Paul Ehrlich, Julian Simon, and Our Gamble Over Earth’s Future has been published by Yale University Press. You can read more about and by Paul Sabin here.

October 8, 2013

Conway’s Game of Life and Three Millennia of Human History

In 01970 John Conway developed a computer program called The Game of Life. The idea behind it was that the process of biological life is, despite its apparent complexity, reduceable to a finite set of rules. The game is made up of a grid of squares, or “cells,” in one of two states: “alive” or “dead.” A player sets the initial conditions, choosing which squares should be alive. Each turn of the game is like a generation – some squares live, some are born, and some die. Just a few simple rules determine cells’ behavior: Cells with too few or too many neighbors die. Empty squares with the right number of neighbors come to life.

This simple set-up, played out by the computer over many generations creates vast complexity that is hard to watch without thinking of life. And, in fact, in 02010 a structure was created within the game by Andrew Wade capable of reproducing itself, much like the real-life molecules that eventually lead to all the living creatures on earth.

The rules in The Game of Life are much simpler than real-life’s actual rules (which we’re a long way from understanding in full), but the point stands that simple rules can produce a shocking amount of complexity and even the possibility of one of life’s hallmarks: reproduction.

By elaborating the rules governing the simulation, could other life-like processes also be modelled? Ecologist Peter Turchin has done just that. He wanted to understand how human societies, not just single organisms, grow and disperse. So, he created a computer simulation not unlike The Game of Life. It’s got a lot more rules, but the basics are similar:

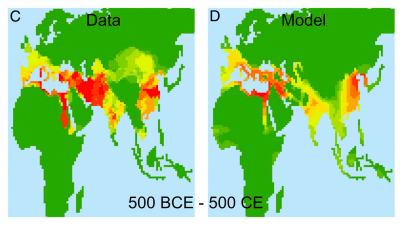

… they divided all of Africa and Eurasia into gridded squares which were each categorized by a few environmental variables (the type of habitat, elevation, and whether it had agriculture in 1500 B.C.E.). They then “seeded” military technology in squares adjacent to the grasslands of central Asia, because the domestication of horses—the dominant military technology of the age—likely arose there initially.

Over time, the model allowed for domesticated horses to spread between adjacent squares. It also simulated conflict between various entities, allowing squares to take over nearby squares, determining victory based on the area each entity controlled, and thus growing the sizes of empires. After plugging in these variables, they let the model simulate 3,000 years of human history, then compared its results to actual data, gleaned from a variety of historical atlases.

The simulation’s predicted history was about a 65% match to actual history, which is a pretty striking result – consider that a coin-flip has two possible outcomes and you’d therefore be able to correctly predict it half the time. Turchin’s model divided Africa and Eurasia into 100km squares – tens of thousands of them. They sampled each square 1,500 times – every 2 years for 3,000 years – assessing sociality and military technology, ultimately allowing the system as a whole to potentially produce on the order of a hundred million outcomes.

That their model matches reality more than half the time isn’t a lucky coin-flip – Turchin and other ecologists have been doing this for animal populations for quite some time. It’s also not Asimov’s Psychohistory, but like The Game of Life, it shows that seemingly complex behavior, be it molecular or societal, can and will increasingly be mathematically modelled and predicted.

October 4, 2013

Expanding the Definition of “Now”

“Humans are good at a lot of things, but putting time in perspective is not one of them. It’s not our fault – the spans of time in human history, and even more so in natural history, are so vast compared to the span of our life and recent history that it’s almost impossible to get a handle on it. If the Earth formed at midnight and the present moment is the next midnight, 24 hours later, modern humans have been around since 11:59:59 pm – 1 second. And if human history itself spans 24 hours from one midnight to the next, 14 minutes represents the time since Christ.”

Given the apparent minuteness of our current lives – and attention spans – in relation to the vast scales of time on which non-human histories play out, what does the concept of “now” really mean?

To help us get a better grasp of that question, the guys over at Wait But Why have created a series of scales that illustrate in graphic color where we fit in the grand scheme(s) of history. Time expands as you scroll down the page, steadily stretching your perspective as it makes a visual argument for a reconceptualization of what we mean by “the present moment.”

October 3, 2013

Alexander Rose Visits Ise Shrine Reconstruction Ceremony

Long Now Executive Director Alexander Rose, also the Project Manager for the 10,000-Year Clock, collects inspiring examples (or in some cases, failures) of long-term thinking, architecture and design. In a talk called Millennial Precedent, he discussed some of these examples and the lessons he draws from them. Among them is a Japanese shrine in the city Ise.

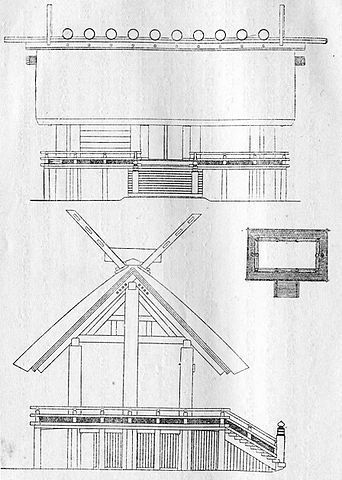

Established an estimated 2,000 years ago, the shrine’s name “Jingu” literally means simply “the shrine.” Few structures on the planet can claim to have stood as long as Ise’s shrine, but the way it has managed to edure is singular. Rather than being constructed at monumental scale, or of immutable materials, the modest thatched-roof and wood structure is ritualistically rebuilt every 20 years. It’s secret isn’t heroic engineering or structural overkill, but rather cultural continuity.

02013 is a reconstruction year and the Shikinen Sengu ceremony marks this milestone. Alexander Rose will attend and share his experiences on our Twitter feed.

This essay by Junko Edahiro provides some great background on the shrine’s origins and long life:

The main sanctuary buildings follow the style of grain warehouses in the Yayoi Period (about 300 BC to 300 AD), which were used to store seed rice for next year and food in case of famine. Should these stocks run out, it would cause serious disruption, so grain warehouses were vital for protecting the people’s lives.

This kind of grain warehouse was normally supported by more than a dozen pillars sunk directly into the ground and had a thatched roof. A great deal of rain usually falls in Japan’s early-summer monsoon, and as the thatched roof absorbs rainwater it becomes heavier. The heavy roof presses down on the walls, and this closes gaps between the wall boards, keeping the inside dry. In summer, the roof dries out and becomes lighter, allowing air to pass through the building and this also keeps it dry. Thus, the roof and pillars function together like a living organism to securely protect the seed rice from moisture and pests.

The only way to support a thatched roof designed to increase in weight is to set the pillars directly into the ground. However, with this method, the pillars and the thatched roof eventually start to rot. Thus, the inevitable solution was to reconstruct these warehouses every 20 to 30 years. However, the life-giving seed rice could not be protected if the rebuilding process started only after the old warehouses could no longer be used. Thus, periodic reconstruction of these structures probably became customary, leading eventually to the Sengu ceremonies of Jingu Shrine in Ise, symbolizing buildings that protect life.

Read on… (and keep an eye on @longnow!)

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers