Stewart Brand's Blog, page 59

February 10, 2014

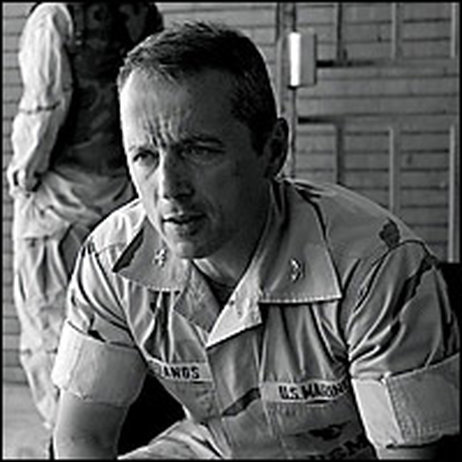

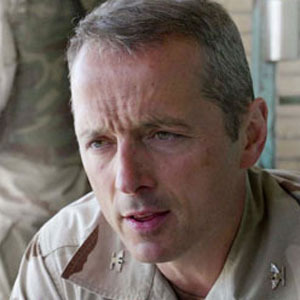

Colonel Matthew Bogdanos Seminar Primer

Credit: Jerome Delay for Associated Press

When we think of the awful consequences of war, the deaths of the soldiers and civilians always remind us that futures have been destroyed – the young man who will never raise a family, or the one-year-old daughter who will never know her father. But war in the third millennium AD has brought us an entirely new and different horror – the destruction of an entire past. What [took] place in southern Iraq [after the American invasion] is nothing less than the eradication of the material record of the world’s first urban, literate civilization. (Gil Stein, Catastrophe! The Looting and Destruction of Iraq’s Past)

Scholars had had a premonition that the war in Iraq would bring looters to the National Museum in Baghdad, home to the world’s largest collection of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts; several Iraqi museums had been plundered during the Gulf War of the early 01990s. Nevertheless, they were powerless to stop it from happening again. In April 02003, mere days after American troops first entered Baghdad and most of the museum staff had sought safety at home, bands of looters forced entry into the galleries and took nearly 15,000 artifacts. US Marine Colonel Matthew Bogdanos had just arrived in Iraq when he heard the news. A career prosecutor with a deep personal interest in ancient civilizations, he headed straight for the capital to launch an investigation and large-scale recovery effort.

Growing up in lower Manhattan as the child of Greek immigrants, Bogdanos first became interested in the Classical world when his mother handed him a copy of Homer’s Iliad at the age of twelve. The military encouraged him to pursue this interest further: he obtained a Master’s in Classics, as well as a law degree, while training to become a Marine Corps officer. Indeed, Bogdanos feels that a military career and intellectual pursuits are natural extensions of one another. As he explained in a 02009 opinion piece for the Washington Post,

Growing up in lower Manhattan as the child of Greek immigrants, Bogdanos first became interested in the Classical world when his mother handed him a copy of Homer’s Iliad at the age of twelve. The military encouraged him to pursue this interest further: he obtained a Master’s in Classics, as well as a law degree, while training to become a Marine Corps officer. Indeed, Bogdanos feels that a military career and intellectual pursuits are natural extensions of one another. As he explained in a 02009 opinion piece for the Washington Post,

… British general Sir William Butler warned a century ago [that] “A nation that will insist upon drawing a broad line of demarcation between the fighting man and the thinking man is liable to find its fighting done by fools and its thinking done by cowards.” It was not always so. We praise classical Greece for philosophy, art and democracy. Yet Athenians knew Socrates, the father of philosophy, for his bravery on the battlefield and Xenophon, author of the epic “Anabasis,” for his generalship. Aeschylus, antiquity’s greatest tragedian, wrote his own epitaph: “This gravestone covers Aeschylus … The field of Marathon will speak of his bravery.” In our time, a steady aggrandizement of self at the expense of society has forced the warrior culture and its ideals to the margins as antique refinements, like knowing classical languages. Yet the most cherished ideal – arête, the classical Greek concept of honor – is anything but passe. Just as “Semper Fidelis” (always faithful) is not merely the Marine Corps motto but a way of life, so is honor a form of mental conditioning – a force-multiplier: Decide in advance to act honorably, and you know without hesitation what to do in a crisis.

Upon resigning from active duty in 01988, Bogdanos joined the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, where his sense of duty and tenacious investigative skills earned him the nickname “pit bull.” Pop culture will remember him best as the prosecutor who failed to convict Sean “P. Diddy” Combs for a 01999 club shooting.

After the Al Qaeda attack of September 11, 02001, Bogdanos was called back to active duty with the Marine Corps. After a brief tour in Afghanistan he was deployed to Iraq, where he was asked to investigate terrorist funding and banned weapons. He had just arrived in Basra when a question from an angry journalist alerted him to the looting at the National Museum in Baghdad. Realizing that its facilities housed a priceless and unique record of the world’s oldest civilization, Bogdanos felt duty-bound to take action. He recalls:

Here I was in Basra, I had the only law enforcement, counterterrorism team that the U.S. Government had in-country. This was a criminal investigation. And we also had enough firepower to at least secure the museum. So I simply decided this was our mission. I know sometimes I get painted as this maverick Marine colonel, but one of the things the Marine Corps instills in you is a seize-the-initiative mentality. It is a Marine Corps philosophy that it is better to beg for forgiveness than ask for permission. So, what I was not going to do was file a request in triplicate in order to go to the museum.

The plundering and destruction of artifacts had begun only days after troops first entered Baghdad. A few remaining members of the museum’s staff had done what they could to safeguard its holdings, but were unable to protect the premises on their own. The looters included professional thieves, but also others – local residents, even government officials and some museum staff, who knew where to find the most valuable objects. Forty artifacts were stolen from the public gallery; more than 13,000 were lifted from the building’s storage rooms and basement.

Scholars had anticipated the war’s destructive impact on the vast collections of ancient ruins and artifacts in Iraq – once the heart of Mesopotamian civilization. Many had spent the months leading up to the invasion in painstaking efforts to document whatever objects and remains they could, hoping to preserve at least a record of what had been there. This would prove helpful in Bogdanos’ mission to recover the looted artifacts. The public availability of records on these items made it difficult for looters to unload them through the antiquities trade – an illegal market that would not only help objects disappear, but also provide a significant source of funding for the insurgency in Iraq. Bogdanos collaborated with scholars at the Oriental Institute in Chicago to create an online catalog of all artifacts that had been taken from the National Museum. In the years since 02003, this database has facilitated the recovery of many artifacts. Many more, however, remain to be found.

… we’re talking about our history, our heritage, our cultural beginnings. … those who do not remember the past are destined to repeat its mistakes. The past is what we have. It’s what we bring with us into the future. I can’t imagine a more important undertaking. (PBS News Hour)

Colonel Matthew Bogdanos received a national humanities medal for his work and wrote a book about the effort. He will discuss the investigation and the continuing, global search for lost artifacts, at the SF JAZZ Center on February 24. You can reserve tickets, get directions, and sign up for the podcast on our Seminar page.

Because this Seminar revolves around and discusses specifics of an ongoing investigation, there will be no recording of any kind. If you are unable to attend in person but would like to know more about Bogdanos’ work, you can read more in his book, Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine’s Passion to Recover the World’s Greatest Stolen Treasures. Thank you for your understanding.

February 6, 2014

The Manual For Civilization Begins

As we near completion on the construction at the new Long Now space in Fort Mason, we are also building the collection of books that will reside here. We have named this collection The Manual for Civilization, and it will include the roughly 3000 books you would most want to rebuild civilization. While this may sound a little apocalyptic, we are not predicting any collapse of civilization. As it turns out, using this as an editing principle just seems to give us a very interesting collection of books.

As we near completion on the construction at the new Long Now space in Fort Mason, we are also building the collection of books that will reside here. We have named this collection The Manual for Civilization, and it will include the roughly 3000 books you would most want to rebuild civilization. While this may sound a little apocalyptic, we are not predicting any collapse of civilization. As it turns out, using this as an editing principle just seems to give us a very interesting collection of books.

So… If you were stranded on an island (or small hostile planetoid), what books would YOU want to have with you? We began asking this question to the Long Now Board and staff, and have now reached out to our Salon supporters and the Long Now members.

We have also begun reaching out to experts and others with great collections and networks.

Author Neal Stephenson selecting books for the Manual For Civilization

This process has just begun, and we will detail these submissions and trips to amazing libraries more in the future, but some of the guest contributors include:

Brian Eno – A list of books on Long-term thinking

Neal Stephenson – A selection of useful history books

Violet Blue – Books on human sexuality

Kevin Kelly – A huge list of appropriate technology and other books from his library

Hugh Howey – Donated a special edition set of his Silo Saga

Ami Burnham – A collection of the best books on reproduction and birth

Alex Steffen – Books on Futurism

Jill Tartar – First Contact

Bruce Sterling – Science Fiction

David Brin – Science Fiction

Kevin Kelly selecting books for the Manual For Civilization

What are these books? In order to make sure we don’t just get a bunch of books on how to make fire, we spread the collection across four basic categories to help guide the collection process:

Cultural Canon (Great Books, Shakespeare, Plato, etc.)

Mechanics of Civilization (Technical knowledge, how to build and understand things)

Rigorous Science Fiction (Science fiction that tells a useful story about a potential future)

Long-term Thinking, Futurism, and relevant history (Books on how to think about the future that may include surveys of the past)

We will be publishing the list in the coming months once we have the suggestions narrowed down by our members and supporters. We have reached about 1400 nominations but will need four to five thousand to have enough to winnow it down to the very best 3000 books. We are not limiting the nominations to western civilization, or even the English language, as one piece of the collection will be the Rosetta Disk itself.

But now that we have a good start on the collection, we need to begin editing the list down. We are using an open source voting system suggested by Heath Rezabek called “All Our Ideas” which has turned out to be a great way to sort lists like this. The system allows our supporters to choose between just two books in a given category, or suggest a new book. This way you don’t have to rank a huge list of books, rather just make decisions between book A or book B and these decisions are aggregated. We are just now sending this system out to our staff and supporters and it is yielding great results. You can see an example of what a voting page looks like below.

Once the Salon is open we hope to have events where people can argue a new book in OR out of the collection. It will be a living collection. The Internet Archive has generously agreed to serve as the digital backup repository of the collection so that anyone with internet access can “check out” the books, or use the list to help create their version of the archive.

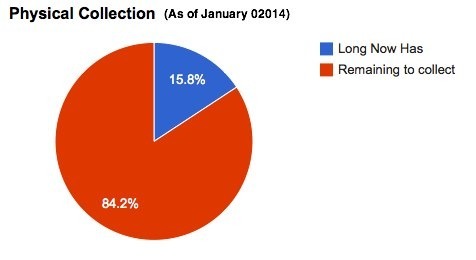

So how can you contribute and share your opinion? The first contributors are our members and Salon supporters. If you have a particular expertise or suggested resource, we welcome you to make book recommendations in the comments of this post. Soon we will also need to begin collecting the actual books for our shelves. We had a fair number of titles in the Long Now library to begin with, but we only have about 15% of the books suggested to date. So once we have the list edited down, we will be asking for book donations to fill in the collection. We are also hoping to work with local book sellers and dealers so that we can get as many used books as possible. Please do leave a comment on this post if you are interested in helping to supply books.

This project was originally conceived in a meeting hosted at the Internet Archive by Brewster Kahle with Kevin Kelly, Rick and Megan Prelinger and Alexander Rose. Past references and writing on this can be found in this Manual for Civilization blog article by Alexander Rose as well in the Library of Utility article by Kevin Kelly. Data wrangling is being ably handled by Kurt Bollacker and Catherine Borgeson with web help by Ben Keating, and the process has also been helped along by Intern Heath Rezabek.

This project was originally conceived in a meeting hosted at the Internet Archive by Brewster Kahle with Kevin Kelly, Rick and Megan Prelinger and Alexander Rose. Past references and writing on this can be found in this Manual for Civilization blog article by Alexander Rose as well in the Library of Utility article by Kevin Kelly. Data wrangling is being ably handled by Kurt Bollacker and Catherine Borgeson with web help by Ben Keating, and the process has also been helped along by Intern Heath Rezabek.

In addition had several volunteers helping with the project that include:

Alison Hunter

Ashley Hennefer

Bryan Campen

Casey Cripe

Danielle Engelman

David Kelley

Elizabeth DeRieux

Nick Gottuso

James Alexander

Jennifer Woodfield

John Kausch

Kurt Bollacker

Ned McFarland

Michael McElligott

Michael Pujals

Alastair Mcpherson

Tim Reynolds

Whitney Deatherage

Mike Johnson

February 4, 2014

Brian Eno and Danny Hillis Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

The Long Now, now

Tuesday January 21, 02014 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Eno and Hillis Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Video is up on the Eno and Hillis Seminar page.

*********************

Make the next legal U-turn – a summary by Stewart Brand

“Bitching Betty,” they call the robotic voice of the car’s GPS guidance system. Eno and Hillis, on their road trips, always become so engrossed in conversation that they get lost—one time, driving to Monterey they wound up in Sacramento, 200 miles wrong. So they turn on GPS, and Betty joins the conversation with helpful advice about U-turns.

Hillis observed, “The GPS is very good at giving you instructions to get someplace. But Brian and I have no idea where we’re going; we just want some time together. What usually happens for us after a couple days of frustratingly looking at the tiny GPS map is that we stop and buy a big paper map. And the moment we open a map of Nevada or Arizona, it feels like we’re in a much bigger world. The big maps are not that useful to navigate by, but there’s a sense of relief of seeing the bigger context and all the possibilities of where we might go. That’s exactly what The Long Now Foundation is for.”

Culture is a long conversation, Eno proposed. “When I talk about the practice of art I often use the word “conversation” because I think that you never see a piece of art on its own. You look at a painting in relation to the whole conversation of paintings. Some things are completely meaningless outside of that kind of context. if you think about Kazimir Malevich’s “White on White” painting, it’s hardly a picture actually, but it’s an important picture in the history of painting up to that point.”

Hillis replied, “My plan for painting is to have my bones removed and replaced with titanium, and then I grind up my bones to make white pigment.” Eno: “That’s very old-fashioned.”

Hillis talked about the long-term stories we live by and how our expectations of the future shape the future, such as our hopes about space travel. Eno said that Mars is too difficult to live on, so what’s the point, and Hillis said, “That’s short-term thinking. There are three big game-changers going on: globalization, computers, and synthetic biology. (If I were a grad student now, I wouldn’t study computer science, I’d study synthetic biology.) I probably wouldn’t want to live on Mars in this body, but I could imagine adapting myself so I would want to live on Mars. To me it’s pretty inevitable that Earth is just our starting point.”

Eno remarked, “Sex, drugs, art, and religion—those are all activities in which you deliberately lose yourself. You stop being you and you let yourself become part of something else. You surrender control. I think surrendering is a great gift that human beings have. One of the experiences of art is relearning and rehearsing surrender properly. And one of the values perhaps of immersing yourself in very long periods of time is losing the sense of yourself as a single focus of the universe and seeing yourself as one small dot on this long line reaching out to the edges of time in each direction.”

Hillis described some elements of surrender designed in to the visitor experience of the 10,000-year Clock being built in the mountains of west Texas. “You’ll be away from your usual environment for days to travel to the remote site. Because of where it is on the mountain, you have to wake up before dawn, and there’s the physical exertion of climbing up the mountain. As you climb, there’s some points of confusion, where you’re not sure if you’re in the right place.

“For example, in the total darkness inside the mountain, as you go up the spiral stairs surrounding the Clock mechanism for hundreds of feet, you think you know where you’re going because there’s light at the top of the shaft that you’re climbing toward, but as you get up there, the stairs keep becoming narrower, and you see they’re tapering off to smaller than you could possibly walk on. And you realize, ‘My plan isn’t going to work.’

“You have to get away from the idea of direct progress and surrender that kind of control in order to find your way.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

February 1, 2014

The New California Water Atlas

Almost forty years ago, California’s young new governor faced the challenge of leading his state through one of its worst droughts ever. Around that time, a group of cartographers had been hoping to develop a comprehensive and definitive atlas of the state and one of them suggested the idea to an advisor to the governor’s office, Stewart Brand. In light of the crisis, a scaled-back, more focused atlas detailing California’s water systems garnered support from members of the administration and governor Jerry Brown.

Several years later, in 01979, California’s Office of Planning and Research published the California Water Atlas, an attempt at “providing the average citizen with a single-volume point of access to understanding how water works in the State of California,” as the volume’s foreword, written by Project Director and Editor William L. Karhl, put it.

Several decades later, California is once again governed by Jerry Brown. Drought has returned and so, coincidentally, has the water atlas. The New California Water Atlas seeks to revive and update the original’s citizen-serving, data-sharing approach by offering online, interactive maps.

Headed up by Laci Videmsky, a project director at the Resource Renewal Institute, The New California Water Atlas operates as a non-profit project, rather than directly out of the Governor’s office. Now moved to the web, it also seeks to publish not a single volume, but a growing body of tools and interactive visualizations with regularly updated data.

Videmsky spoke with me about the project from Berkeley, where he also lectures for the College of Environmental Design at the University of California. He described at length how the original Water Atlas inspired this new project and about what’s in store.

Videmsky first encountered the original Atlas when his wife brought it home from UC Berkeley’s library. “Both of us were in awe,” he says.

Around this time, Videmsky explains, he’d been exploring the world of web mapping, open data and open government:

I was really interested in the ethos of open government and how people were using data, thinking about transparency and accountability, and how their systems communicate with government and the kinds of technologies they were using to connect people. And most of this work was being done at the city level and then at the federal level and also most of it was related to various amenities and services that were often not natural resources, so I wondered, why don’t we take this open government and open data to natural resources agencies? They are civic institutions and they could benefit from this.

One area he began researching was California’s system of granting water rights.

I was learning how to do web mapping and I called the state water board to download their data from their site. They had kind of an older application that they’d built a while back that kind of half works and doesn’t have an easy way to search or to download data, and they were actually nice enough to just give me their whole data set.

Not long after these extracurricular efforts, he walked into the office of Huey Johnson, founder and president of the Resource Renewal Institute (and a former SALT speaker), and noticed a copy of the Water Atlas. Johnson had been the Secretary for Resources in Jerry Brown’s first administration and served on the Water Atlas’s advisory board along with Stewart Brand. They got to talking about the original Atlas, as well as some of Videmky’s efforts to visualize water data.

I showed him this interactive map that I’d made with the water board data and the lightbulb went off and we started having conversations about open government and how open data’s kind of changing the way government works and how we can maybe do that for California water.

It was out of that conversation that the New California Water Atlas was born and from that early prototype map that the site’s first big visualization would eventually grow. Videmsky and others are currently working on two more interactives for the site, with hopes of many more being developed as the project grows. The first focuses on groundwater levels:

We’re working on groundwater – so another state agency called the Department of Water Resources, which actually funded the first atlas, they have a data set of all the water levels in the ground of about 15,000 groundwater elevation monitoring wells. We downloaded from their water elevation monitoring system about 500,000 records which represents about 30 years of data for the whole state. It was very laborious – it took us a month to get 30 years.

Using the final product, Californians will be able to zoom into an area of the state on a map and move a slider to view the last 30 years of fluctuations in groundwater levels.

Another interactive in the pipeline will track water prices across the state:

I’m starting a collaboration with the California Public Utilities Commission to make data available to visualize water prices. Water isn’t priced according to scarcity, it’s priced according to the price of delivering the water. So I think it’d be really, really interesting for people to be able to compare what they paid for water.

Something Videmsky has found to be consistent with the original Atlas is the eagerness of state agencies to share their data, despite budgetary and technical challenges. Stewart Brand wrote in the original’s afterword:

Some of it was easier than expected. The state government probably has more information on water than any other subject, but early fears that the information would be jealously guarded by the agencies turned out to be incorrect. At every level, from local to state to federal, people were generous with their data and their time.

As Videmsky put it:

A lot of state agencies don’t have the resources either in staff or money to improve the way they make water understandable and water data available to the public. And so there’s definitely a need for private-public partnerships and that’s actually happening in many different sectors. We get a lot of moral support from the agencies. They’re very excited about this. We’re making something that’s very visible, highly accessible and so they’re really eager to participate.

Beyond helping the state’s agencies tell their stories, Videmsky is also exploring the idea of making a platform for citizens to tell theirs as well.

One idea – this is not implemented – but one idea is to allow for, almost a site within a site so a user would be able to create a blog around a certain geographic area. They’re dealing with issues locally that are important to them, like groundwater contamination, so it’d almost be like a citizen atlas, where citizens’ science sits alongside authoritative data. There are a lot of stories to tell that are not necessarily data stories but personal stories.

Additionally, they’re looking for help from programmers, translators (they want the site to be in both English and Spanish), designers and data-wranglers. Much of their work is open-sourced on GitHub, where they’d be happy for help building part of the visualizations or cleaning up the data.

Keeping the project open-source isn’t just a collaborative choice, though. Videmsky sees it as a way to help the project bear long-term fruit. While the original Atlas was a single volume, the web will allow the new Atlas to live and grow along with the state and possibly to be adopted by other states or for analyzing other natural resources. Along other long-term lines, Videmsky said they’re looking for a good institutional partner to help support and archive the data so that the database of California’s water system they hope to build can continue to grow and inform the state’s citizens for generations to come.

January 29, 2014

Colonel Matthew Bogdanos Seminar Tickets

The Long Now Foundation’s monthly

Seminars About Long-term Thinking

Colonel Matthew Bogdanos on “The Unlooting of Civilization’s Treasures in Wartime Iraq”

TICKETS

Monday February 24, 02014 at 7:30pm SFJAZZ Center

Long Now Members can reserve 2 seats, join today! General Tickets $15

Please note that because this talk revolves around and discusses the specifics of what is still an on-going investigation, there will not be any recording of any kind–audio or visual, nor a live stream for members.

Thank you for your understanding.

About this Seminar:

Destruction is easy. Recovery is hard. Destruction is big news. Recovery is the real news.

In April 02003 when Baghdad fell to US forces, the renowned Iraq Museum was looted of thousands of civilization’s most ancient and unique treasures, and the international press reacted with outrage. Marine Colonel Bogdanos, who had advanced degrees in Classical Studies and Law, rushed to Baghdad with a team of special-forces volunteers to recover the lost artifacts. Two years later he could write in the American Journal of Archaeology, “Working closely with Iraqis and using a complex methodology that includes community outreach, international cooperation, raids, seizures, and amnesty, the task force and others around the world have recovered more than 5,000 of the missing antiquities.“ (That was out of some 15,000 items stolen. The total of recovered antiquities is now over 10,000, with more still turning up.)

Matthew Bogdanos is a homicide prosecutor with the district attorney’s office in New York City and a middleweight boxer. He continues to serve in the US Marine Corps Reserve, where his nickname is “Pit Bull.”

For members unable to attend in person, you can learn more about the investigation through Colonel Matthew Bogdanos’ book, Thieves of Baghdad. The book will be for sale at the Seminar.

January 28, 2014

An Animated Atlas of The Known World

In 01830, English journalist Edward Quin created a historical atlas that illustrated our expanding knowledge of the world. Depicting a time span that stretched from 02348 BC to 01828 AD, or more than four millennia, each successive map showed a slightly larger piece of bright, colorful land, surrounded by the ominous clouds of the unknown.

Slate recently compiled these maps into a single, chronological GIF (high res version) that highlights the sense of dynamism, evolution, and enlightenment that Quin sought to convey. As each image follows its predecessor, the viewer sees a menacing black sky gradually receding until the modern world is finally revealed.

The atlas, which belongs to Long Now Board member David Rumsey‘s map collection, certainly tells a story – though it may not be the one Quin sought to tell. To a modern audience, these maps are less an account of expanding geographic knowledge than a history of Western thinking about the rest of the world. The maps depict a decidedly European perspective, beginning with the biblical world of Noah’s Ark, and progressing, via ages of imperial conquest (Alexander the Great, the Roman Empire, and finally colonialism), to incorporate the entire globe. As Slate summarizes:

To say that an area of the world was “known” was, for Quin, the same as saying that it was “known” by Greek, Roman, or European cartographers. A set of such maps drawn from the perspective of the Aztecs, Egyptians, or Chinese would, of course, look quite different.

For more information about the atlas, please visit David Rumsey’s online collection, where each map – with descriptions by Quin – can be examined on its own.

January 24, 2014

Brian Eno and Danny Hillis Seminar Media

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

This lecture was presented as part of The Long Now Foundation’s monthly Seminars About Long-term Thinking.

The Long Now, now

Tuesday January 21, 02014 – San Francisco

Audio is up on the Eno and Hillis Seminar page, or you can subscribe to our podcast.

*********************

Make the next legal U-turn – a summary by Stewart Brand

“Bitching Betty,” they call the robotic voice of the car’s GPS guidance system. Eno and Hillis, on their road trips, always become so engrossed in conversation that they get lost—one time, driving to Monterey they wound up in Sacramento, 200 miles wrong. So they turn on GPS, and Betty joins the conversation with helpful advice about U-turns.

Hillis observed, “The GPS is very good at giving you instructions to get someplace. But Brian and I have no idea where we’re going; we just want some time together. What usually happens for us after a couple days of frustratingly looking at the tiny GPS map is that we stop and buy a big paper map. And the moment we open a map of Nevada or Arizona, it feels like we’re in a much bigger world. The big maps are not that useful to navigate by, but there’s a sense of relief of seeing the bigger context and all the possibilities of where we might go. That’s exactly what The Long Now Foundation is for.”

Culture is a long conversation, Eno proposed. “When I talk about the practice of art I often use the word “conversation” because I think that you never see a piece of art on its own. You look at a painting in relation to the whole conversation of paintings. Some things are completely meaningless outside of that kind of context. if you think about Kazimir Malevich’s “White on White” painting, it’s hardly a picture actually, but it’s an important picture in the history of painting up to that point.”

Hillis replied, “My plan for painting is to have my bones removed and replaced with titanium, and then I grind up my bones to make white pigment.” Eno: “That’s very old-fashioned.”

Hillis talked about the long-term stories we live by and how our expectations of the future shape the future, such as our hopes about space travel. Eno said that Mars is too difficult to live on, so what’s the point, and Hillis said, “That’s short-term thinking. There are three big game-changers going on: globalization, computers, and synthetic biology. (If I were a grad student now, I wouldn’t study computer science, I’d study synthetic biology.) I probably wouldn’t want to live on Mars in this body, but I could imagine adapting myself so I would want to live on Mars. To me it’s pretty inevitable that Earth is just our starting point.”

Eno remarked, “Sex, drugs, art, and religion—those are all activities in which you deliberately lose yourself. You stop being you and you let yourself become part of something else. You surrender control. I think surrendering is a great gift that human beings have. One of the experiences of art is relearning and rehearsing surrender properly. And one of the values perhaps of immersing yourself in very long periods of time is losing the sense of yourself as a single focus of the universe and seeing yourself as one small dot on this long line reaching out to the edges of time in each direction.”

Hillis described some elements of surrender designed in to the visitor experience of the 10,000-year Clock being built in the mountains of west Texas. “You’ll be away from your usual environment for days to travel to the remote site. Because of where it is on the mountain, you have to wake up before dawn, and there’s the physical exertion of climbing up the mountain. As you climb, there’s some points of confusion, where you’re not sure if you’re in the right place.

“For example, in the total darkness inside the mountain, as you go up the spiral stairs surrounding the Clock mechanism for hundreds of feet, you think you know where you’re going because there’s light at the top of the shaft that you’re climbing toward, but as you get up there, the stairs keep becoming narrower, and you see they’re tapering off to smaller than you could possibly walk on. And you realize, ‘My plan isn’t going to work.’

“You have to get away from the idea of direct progress and surrender that kind of control in order to find your way.”

Subscribe to our Seminar email list for updates and summaries.

January 23, 2014

The Oldest Telephone in the Western Hemisphere

Among its collection of some 137 million artifacts, the Smithsonian houses a unique piece of technology. Made of two hollowed-out gourds and a 75-foot length of twine, it’s the oldest example of telephone technology from the Western hemisphere – and it’s about 1,300 years old.

The object, featured recently in an article for Smithsonian Magazine, was made by the Chimu, a civilization that flourished in Peru for more than 500 years – until they were wiped out by the Inca around 01470.

Chimu society occupied an arid strip of land between the Pacific Ocean and the Western Andes. Its legacy is often eclipsed by that of the Inca, but the Chimu were well-known in their day for advanced artisanship and sophisticated social stratification. At its peak, the capital of Chan Chan was the largest city in pre-Columbian America. Spread out over about 3.8 square miles, its nine citadels were home to as many as 30,000 citizens, and formed the structural basis for a complex social hierarchy.

According to Ramiro Matos, curator at the National Museum of the American Indian, the Chimu were also skilled and inventive engineers.

The Chimu, [he] explains, were the first true engineering society in the New World, known as much for their artisanry and metalwork as for the hydraulic canal-irrigation system they introduced, transforming desert into agricultural lands.

Their advanced irrigation system fostered a strong agriculture-based economy and allowed society to flourish – enough, it seems, to encourage some exploration of technology as a way to sustain social hierarchies. The ancient telephone now in the Smithsonian collection, Matos surmises, must have been

“a tool designed for an executive level of communication” – perhaps for a courtier-like assistant required to speak into a gourd mouthpiece from an anteroom, forbidden face-to-face contact with a superior conscious of status and security concerns.

It’s impossible to determine whether this recovered sound-transmission device was a one-of-a-kind prototype, or simply the only surviving representative of a common appliance. But in either case, the object signals a moment of revolutionary – and inspiring – technological advancement for its day.

Contemplating the brainstorm that led to the Chimu telephone – a eureka moment undocumented for posterity – summons up its 21st-century equivalent. On January 9, 2007, Steve Jobs strode onto a stage at the Moscone Center in San Francisco and announced, “This is the day I have been looking forward to for two and a half years.” As he swiped the touchscreen of the iPhone, it was clear that the paradigm in communications technology had shifted. The unsung Edison of the Chimu must have experienced an equivalent, incandescent exhilaration when his (or her) device first transmitted sound from chamber to chamber.

January 22, 2014

Hugh Howey’s Dystopian Silo Saga Joins the Manual for Civilization

Science fiction author Hugh Howey donated to the Manual for Civilization a one-off hard cover set of his Silo Saga with a special title page for The Long Now Foundation.

The dystopian science fiction series developed out of a single novella Hugh Howey self-published on the Web in 02011. He continued the story with four more installments, which now comprise the Omnibus edition of Wool. Shift (books 6-8) are a prequel to Wool (books 1-5), Dust is the conclusion.

Without giving away any spoilers, each story has its own resolution, adds clarity and answers questions from the last, but then creates some larger questions:

What would human beings be like if for several hundred years they had been forced to live in a giant container, a refuge from the destruction of the planet? Would we recognize them? Would they have changed? Would we understand their concerns and desires? Our ubiquitous human nature and some of its seemingly unchanging characteristics are major themes in Howey’s Wool. Tens of thousands of people are packed into a silo buried in the Earth, protected from the toxic atmosphere which surrounds it. Yet despite hundreds of years, the occupants still long to explore, to expand their horizons. Howey explores the traditions, mores and laws necessary to protect this remnant of humanity from the creative urges and deep desires which always seek to push beyond the safe confines of the silo into the unknown. -GeekDad, Wired Magazine

January 21, 2014

Nature, Cities, and Long-term Thinking

In 01995, Brian Eno surmised that the fast-paced uncertainty of life in New York City led people to retreat into the immediacy of their own private worlds. As a counterweight to this preoccupation with the “short now,” he posited the idea of “The Long Now” – and thus the name of our Foundation was born.

Now, nearly twenty years later, a group of researchers from the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam argues that urban environments may indeed directly impede our capacity for long-term thinking.

Their work is predicated on evolutionary theories of competition. In an environment with scarce resources for nutrition and reproduction, their paper explains, life is uncertain and survival depends on an organism’s success in securing as many of those resources as he can, as fast as he can. When surrounded by abundance, on the other hand, the need to compete is less acute. Organisms can afford to take it easy: there will still be apples in that tree tomorrow, and there’s no risk that that nearby stream will run dry any time soon. In other words: a lush environment creates the probability of a future. It allows species the opportunity to maximize their evolutionary success by weighing short-term gains against long-term rewards.

This team of Dutch social psychologists hypothesized that urban environments will trigger a perception of scarcity and uncertainty in the human brain, whereas natural surroundings will elicit a sense of abundance and stability:

Urban landscapes are inherently unpredictable as they convey intense social competition for status, goods and mates, and so they may entice people – either consciously or subconsciously – to adopt a faster life history. By contrast, nature exposure may encourage individuals to adopt a slower life-history strategy, perhaps because natural environments convey an abundance of natural resources, and hence less competition.

Indeed, their series of three experiments has confirmed that people who have been exposed to a natural environment are more inclined to consider the future than those who have been immersed in an urban setting. In the first two of these tests, research participants were shown a selection of photographs that depicted either an urban or natural landscape; in the third, subjects were actually taken to a high-rise neighborhood or local forest. Following this ‘exposure’, all participants were asked to choose between an immediate reward of €100, or a larger reward – anywhere between €110 and €170 – to be paid out in ninety days. Those who had been exposed to natural settings were systematically more likely to choose the delayed reward – and to do so when the reward was set at a lower amount, suggesting a greater propensity to consider the future – than those who had been exposed to urban environments.

As the authors conclude, these findings have profound implications for global society – especially given today’s rate of urbanization. But there is cause for optimism: these studies also suggest that fostering long-term thinking may simply start by encouraging people to take a walk in the woods.

Stewart Brand's Blog

- Stewart Brand's profile

- 291 followers