Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 27

December 31, 2012

My 2013 Writing Resolution

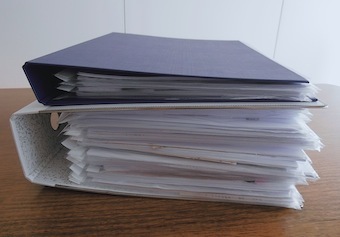

It was only last year that I finally started to think of myself as a ‘writer’ but ironically, 2012 was the year in which I did very little writing. Oh, I wrote plenty of blog posts, here at Memoranda and in various other places; I finished editing one book and did mountains of research for my next book; I even wrote a short story. But I didn’t actually do any novel writing, and that’s a problem, because novel writing is the only writing that has ever earned me any money (not very much money, admittedly, but some). Then I realised that I hadn’t made any writing resolutions at the start of 2012. Well, no wonder I didn’t achieve anything! So, here is my writing resolution for 2013. I am going to try to turn this pile of research notes

into a novel. Then, hopefully, someone will want to publish it. I am not feeling wildly optimistic about either of these two things, but still, there’s my writing resolution for 2013.

For those of you who were more productive in 2012 than I was and already have a finished YA manuscript, you may be interested in Hardie Grant Egmont’s Ampersand Project. They are looking for debut YA manuscripts, with submissions closing on January 31st, 2013. (I love that they felt the need to specify that manuscripts be submitted in “readable typeface . . . No Comic Sans or Monotype Corsiva, please.”) Best of luck to those sending off manuscripts in 2013, and a happy new year to you all.

December 22, 2012

My Favourite Books of 2012

Here are the books I read this year that I loved the most.

But first, some statistics!

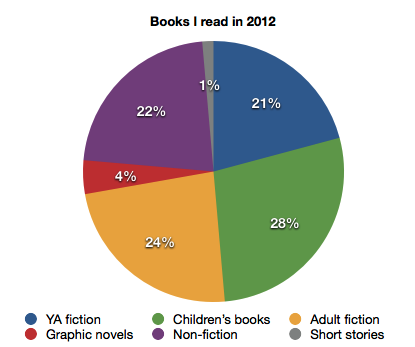

I read 72 books this year, plus approximately 7,853 articles in scientific journals (this last number may be a slight exaggeration). I’m sure you really, really want to see some pie charts about the books I read, so here you go:

I read lots more children’s books this year than I usually do.

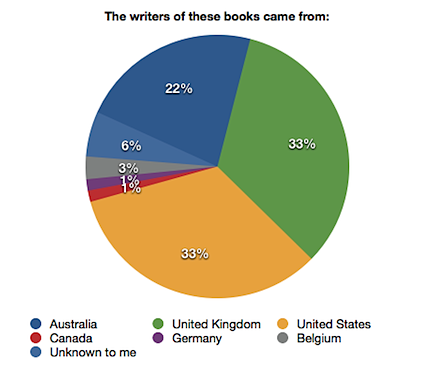

Hmm, that is not very diverse, is it? I only read three books that had been translated into English, too.

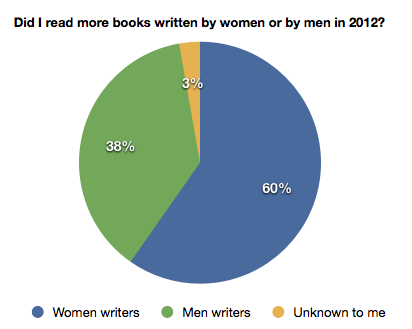

That’s probably typical of my reading habits. It’s not that I deliberately try to read more women writers than men, it simply works out that way most years.

Now for my favourites.

My favourite children’s books

I absolutely loved Saffy’s Angel by Hilary McKay, which I have previously written about here. I also liked Amelia Dee and the Peacock Lamp by Odo Hirsch, a sweet, charming story about a girl who is inspired to write stories by a mysterious brass lamp she finds in her house. This has many of the usual elements of an Odo Hirsch book (eccentric but benevolent parents, a carefully multicultural cast of characters, a vaguely European setting), but I found Amelia especially endearing and the lessons she learned (that it takes courage to share your thoughts with others; that other people often have complex motivations for their actions; that unchecked anger harms yourself, not just others) were exactly what I needed to think about at the time.

I absolutely loved Saffy’s Angel by Hilary McKay, which I have previously written about here. I also liked Amelia Dee and the Peacock Lamp by Odo Hirsch, a sweet, charming story about a girl who is inspired to write stories by a mysterious brass lamp she finds in her house. This has many of the usual elements of an Odo Hirsch book (eccentric but benevolent parents, a carefully multicultural cast of characters, a vaguely European setting), but I found Amelia especially endearing and the lessons she learned (that it takes courage to share your thoughts with others; that other people often have complex motivations for their actions; that unchecked anger harms yourself, not just others) were exactly what I needed to think about at the time.

Other books I enjoyed included The Word Spy, an entertaining non-fiction book about the history of the English language, written by Ursula Dubosarsky and illustrated by Tohby Riddle, and Al Capone Shines My Shoes by Gennifer Choldenko, about a boy whose father is a guard at Alcatraz Prison in 1935.

My favourite Young Adult novel

This year I read quite a few YA books that had received plenty of acclaim, but I ended up feeling underwhelmed by a lot of them. I could certainly understand why the books had been praised, but they just weren’t my cup of tea. Sometimes they had beautiful sentence-level writing, but the voice seemed implausible for the teenager who was supposed to be narrating the story. Sometimes they had a great narrator and fascinating premise, but the structure of the novel didn’t work for me. One book I’d seen described as ‘feminist’ was . . . really, really not feminist at all. Maybe my expectations had been raised too high by the hype. Anyway, my favourite YA book of 2012 turned out to be a book first published in 1910, long before the concept of ‘Young Adult literature’ existed. The book was The Getting of Wisdom, by Henry Handel Richardson, which I’ve previously written about here.

My favourite novels for adults

I found At Last by Edward St Aubyn quite as harrowing as I’d expected, but also hopeful and consoling and unexpectedly funny. It’s the fifth in a series of novels about Patrick Melrose, who was born into a wealthy, aristocratic family and was then subjected to appalling childhood abuse and neglect by his parents. In this book, Patrick has finally overcome his drug and alcohol addictions and is trying to cope with his marriage breakdown, when his mother dies. The novel is elegantly structured around her funeral, allowing a lot of thoughtful commentary on the nature of death, forgiveness and free will, but also some hilarious descriptions of the idle rich. Patrick’s awful relatives and family friends are mostly ‘old money’ who’ve never worked a day in their lives, but complain constantly about how difficult their existence is. I know this all sounds very grim and this book certainly isn’t for everyone, but I thought it was fascinating and beautifully written.

I found At Last by Edward St Aubyn quite as harrowing as I’d expected, but also hopeful and consoling and unexpectedly funny. It’s the fifth in a series of novels about Patrick Melrose, who was born into a wealthy, aristocratic family and was then subjected to appalling childhood abuse and neglect by his parents. In this book, Patrick has finally overcome his drug and alcohol addictions and is trying to cope with his marriage breakdown, when his mother dies. The novel is elegantly structured around her funeral, allowing a lot of thoughtful commentary on the nature of death, forgiveness and free will, but also some hilarious descriptions of the idle rich. Patrick’s awful relatives and family friends are mostly ‘old money’ who’ve never worked a day in their lives, but complain constantly about how difficult their existence is. I know this all sounds very grim and this book certainly isn’t for everyone, but I thought it was fascinating and beautifully written.

I also enjoyed Insignificant Others by Stephen McCauley and The Beginner’s Goodbye by Anne Tyler, which I’ve previously written about here. I’m currently halfway through Restoration by Rose Tremain and loving it, so I suspect this book will make it onto my 2012 favourites list, too.

My favourite non-fiction for adults

I read some terrific biographies this year, including A. A. Milne: His Life by Ann Thwaite and Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA by Brenda Maddox. I wrote about both books here. I also enjoyed Alex and Me, by Irene M. Pepperberg, about a very smart parrot.

I will not bore you with my To Read list for 2013, especially as it contains approximately 2,147 scientific articles1 that I didn’t get around to reading this year (this number may be a slight exaggeration).

Hope you all have a happy and peaceful holiday season, and that 2013 brings you lots of great reading.

More favourite books:

1. Favourite Books of 2010

2. Favourite Books of 2011

_____

Yes, it’s research for my next book. The book that was supposed to need far less research than my last book. Ha ha ha. ↩

December 15, 2012

The Spent Deep Feigns Her Rest . . .

Today’s poem is by Rudyard Kipling, who held some very unappealing beliefs about war and empire-building and The White Man’s Burden, but also wrote some excellent children’s books. He even won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907. This particular poem is quoted by Sophie in A Brief History of Montmaray, and is best read aloud while stomping about the deck of a sailing ship.

Warning: this poem may be seen by some as amoral, as the narrator firmly declares that he does not want to work in a church.

The Bell Buoy

They christened my brother of old—

And a saintly name he bears—

They gave him his place to hold

At the head of the belfry-stairs,

Where the minster-towers stand

And the breeding kestrels cry.

Would I change with my brother a league inland?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

In the flush of the hot June prime,

O’er sleek flood-tides afire,

I hear him hurry the chime

To the bidding of checked Desire;

Till the sweated ringers tire

And the wild bob-majors die.

Could I wait for my turn in the godly choir?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

When the smoking scud is blown—

When the greasy wind-rack lowers—

Apart and at peace and alone,

He counts the changeless hours.

He wars with darkling Powers

(I war with a darkling sea);

Would he stoop to my work in the gusty mirk?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not he!

There was never a priest to pray,

There was never a hand to toll,

When they made me guard of the bay,

And moored me over the shoal.

I rock, I reel, and I roll—

My four great hammers ply—

Could I speak or be still at the Church’s will?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

The landward marks have failed,

The fog-bank glides unguessed,

The seaward lights are veiled,

The spent deep feigns her rest:

But my ear is laid to her breast,

I lift to the swell—I cry!

Could I wait in sloth on the Church’s oath?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

At the careless end of night

I thrill to the nearing screw;

I turn in the clearing light

And I call to the drowsy crew;

And the mud boils foul and blue

As the blind bow backs away.

Will they give me their thanks if they clear the banks?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not they!

The beach-pools cake and skim,

The bursting spray-heads freeze,

I gather on crown and rim

The grey, grained ice of the seas,

Where, sheathed from bitt to trees,

The plunging colliers lie.

Would I barter my place for the Church’s grace?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

Through the blur of the whirling snow,

Or the black of the inky sleet,

The lanterns gather and grow,

And I look for the homeward fleet.

Rattle of block and sheet—

‘Ready about—stand by!’

Shall I ask them a fee ere they fetch the quay?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

I dip and I surge and I swing

In the rip of the racing tide,

By the gates of doom I sing,

On the horns of death I ride.

A ship-length overside,

Between the course and the sand,

Fretted and bound I bide

Peril whereof I cry.

Would I change with my brother a league inland?

(Shoal! ’Ware shoal!) Not I!

‘Storm on the Sea’ by Johannes Christiaan Schotel, c 1825

December 6, 2012

Book Banned, Author Bemused

I’ve previously written about my books being edited so that the vocabulary, punctuation and spelling make sense to overseas readers. However, I didn’t mention another issue, which is that different countries often have very different cultural values. Contrast, for example, attitudes (and legislation) in Australia and the United States regarding gun ownership, capital punishment and universal healthcare. And also, book banning.

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by Magpies (an Australian journal about literature for children and teenagers) and was asked about the reaction of US readers to the epilogue of The FitzOsbornes at War. As the book hadn’t yet been released in the US, I talked about reactions to the previous two books. I said I’d always expected some US reviewers and readers would object to my gay and bisexual characters, but that I’d been surprised by some of the things they’d also deemed ‘controversial’ – for example, that some of my characters were atheists or socialists, that not all of the married couples were happily married, and that there was a brief discussion of contraception. One US reviewer of The FitzOsbornes in Exile complained at length about the “sketchy moral questions that permeate the book” and hoped that there’d be some signs of moral improvement in Book Three. Um . . . well, not really.

Earlier this year, I was interviewed by Magpies (an Australian journal about literature for children and teenagers) and was asked about the reaction of US readers to the epilogue of The FitzOsbornes at War. As the book hadn’t yet been released in the US, I talked about reactions to the previous two books. I said I’d always expected some US reviewers and readers would object to my gay and bisexual characters, but that I’d been surprised by some of the things they’d also deemed ‘controversial’ – for example, that some of my characters were atheists or socialists, that not all of the married couples were happily married, and that there was a brief discussion of contraception. One US reviewer of The FitzOsbornes in Exile complained at length about the “sketchy moral questions that permeate the book” and hoped that there’d be some signs of moral improvement in Book Three. Um . . . well, not really.

But I suppose it depends on how you define ‘moral’. I think The FitzOsbornes at War is all about morality, but I quite understand that some readers won’t approve of some of the characters’ actions. It’s a novel full of conflict and drama and people in extreme circumstances making difficult (and occasionally stupid) decisions. But reading about characters doing things that you regard as against your own personal moral code is not the same as doing those things yourself. For instance, teenagers reading about a gay character will not suddenly turn gay (unless they already are gay, in which case what they read will make no difference to who they are, but might possibly make them feel less alone). Will reading about such ‘immoral’ behaviour make the behaviours seem more ‘normal’, more ‘acceptable’? Well, maybe. The US librarian who’s pulled The FitzOsbornes at War off her library shelves certainly seems to think so.

Note: Sorry, I’m going to have to include plot spoilers for The FitzOsbornes at War here. If you haven’t read the book but are planning to read it, you might want to skip the next seven paragraphs of this post.

I’m not going to link to the librarian’s review, because I don’t want anyone to go over there and hassle her. (Not that you would – I know the people who regularly visit this blog are always respectful and courteous, even when they disagree with a post – but just in case someone else does.) Still, I found the librarian’s reasons for removing the book really interesting, so I would like to quote from her review, which awarded the book one star out of five:

“Does it not bother anyone that this novel seems to have characters that are entirely amoral? I was wondering whether to overlook the PG13 content and language because of the educational aspects of this well researched historical fiction World War II novel, but really–I just have to wonder about everyone being okay with the gay king living with his wife and his wife’s lover and their children in happy wedded bliss (This was a recommended book in the Parent’s Choice awards!)…Sorry this one is not staying at our library.”

Firstly, as far as I know, the book isn’t recommended in the Parents’ Choice awards. A Brief History of Montmaray was, several years ago, but The FitzOsbornes at War hasn’t been.

Secondly, is it just me or does it read as though it’s okay to have a gay character in a book, but only if he’s utterly miserable? Heaven forbid that gay people and their children could ever live in “happy wedded bliss”, either in books or in real life. Oh, wait, some people’s version of heaven does forbid it . . .

Thirdly, if the “content and language” is regarded by the librarian as PG13, doesn’t that mean that this book should be okay to shelve in the Young Adult fiction section? Shouldn’t it be suitable for readers over thirteen, with some parental guidance if necessary? Can’t teenage readers and their parents decide for themselves whether they want to read this book?

Fourthly, does this librarian truly believe the characters in The FitzOsbornes at War are “entirely amoral”? The word ‘amoral’ doesn’t mean ‘disagrees with my own moral values’. It refers to someone who has no understanding of morality, no sense of right and wrong. I’m assuming the librarian is referring to Toby, Julia and Simon, given the reference to the “gay king” and his family (although, who knows, perhaps Veronica and Sophie are included in the condemnation, for having had sexual experiences outside marriage). Really, these characters are “amoral”? In a novel that also contains Hitler, Stalin and Franco? So, should all books with amoral characters be banned from libraries? I’m guessing that particular library doesn’t have a copy of Richard III or Macbeth, either. (Not that I’m for one moment suggesting that my novels approach the literary quality of the works of William Shakespeare. But it seems ‘literary quality’ isn’t a factor in determining which books are stocked at this library, anyway.)

(Fifthly, and quite irrelevantly, did the librarian really describe Simon as the “wife’s lover”? Poor Toby! You’d think he’d have more of a claim as Simon’s lover than Julia, after all those years.)

This is where the cultural difference thing comes in, because I am trying, and failing, to imagine a librarian in an Australian public library taking The FitzOsbornes at War off her library’s shelves – not because a library patron had complained, but because the librarian herself thought the book ‘amoral’. Australia has a long history of banning books, but it would be very unusual for a book in an Australian public library to be challenged or banned nowadays, particularly if the only objection to the book was that it contained a gay character who was happy.

Still, I’m in pretty good company. Here are some of the books that were most frequently banned or challenged in US libraries between 2000 and 2009:

The Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

His Dark Materials series by Philip Pullman

To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

The Giver by Lois Lowry

Bridge To Terabithia by Katherine Paterson

Beloved by Toni Morrison

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeline L’Engle

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Fahrenheit 451? Seriously, a novel about books being outlawed in America is on the US banned books list? I can only shake my head and turn to John Stuart Mill, who’s quoted on the American Library Association’s website:

“. . . But the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”

December 2, 2012

Holiday Book Giveaway Winners

Thank you to all those who shared their favourite holiday reads with us. I am especially impressed that each time I hold a giveaway these days, there’s at least one reader who takes the time to share her favourite books with us and doesn’t even want to be entered into the contest because she’s previously won a book. Because that’s the sort of generous, selfless reader who hangs out at this blog. I’d also like to take this opportunity to thank Rockinlibrarian for her tireless efforts in promoting Montmaray and for being the best American Ambassador that Montmaray has ever had. (Okay, she’s the only American Ambassador that Montmaray has ever had, but that just makes her job more challenging, because she has to make it up as she goes along.)

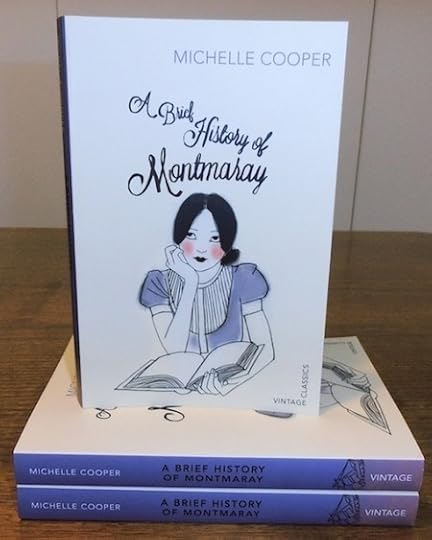

Congratulations to Kim, Elizabeth and Genevieve, who have each won a Vintage Classics edition of A Brief History of Montmaray. To those who missed out this time, keep an eye on The Book Smugglers, because they’ll be giving away a copy of the book soon. (Well, sometime in the next few weeks. I’ll put up a link here when it happens.)

November 24, 2012

Vintage Classics Holiday Book Giveaway

I still have a few copies of the Vintage Classics edition of A Brief History of Montmaray. I’m sure they’d be happier spending Christmas with someone who’d appreciate them than sitting by themselves in a dark box in my wardrobe, so I’m having a holiday book giveaway this week.

For a chance to win one of these three books, leave a comment below telling us about a good read for the holidays. I’ll leave it up to you to define ‘good read’ and ‘holidays’. (As for me, I’m thinking that if I have some spare reading time these holidays, I’d like to try the first book of the Mapp and Lucia series by E. F. Benson, and maybe Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome.)

Conditions of entry:

1. This is an international giveaway. Anyone can enter.

2. Make sure the email address you enter on the comment form is a valid email account that you check regularly, so I can contact you if you win (no one will be able to see your email address except me, and I won’t show it to anyone else). Please don’t include your real residential or postal address anywhere in the comment. However, it would be nice if you mentioned which country you live in, because I’m curious about who reads this blog.

3. The three winners will be chosen at random, unless there are three or fewer comments – in which case, it won’t be random and all will win prizes.

4. This contest and/or promotion is not sponsored or authorised by Random House Australia. Random House Australia bears no legal liability in connection with this contest and/or promotion. (My Australian publishers say I have to put this bit in.)

5. Entries close at the end of Saturday, 1st of December, 2012. The winners will be emailed then, and I will send off the winners’ books as soon as possible after that. (Winners should receive the books before Christmas, but I can’t guarantee it.)

November 20, 2012

Montmaray Book Giveaway

Jean BookNerd is giving away a hardcover edition of The FitzOsbornes at War this month. There’s an interview with me at her blog, too.

In more exciting news, Series Four of Horrible Histories has just been released on DVD! Ooh, I know what I’m getting myself for Christmas . . .

November 16, 2012

Montmorency

Having devoted an entire blog post to a cat, it’s only fair that I give dogs their turn during Animal Month here at Memoranda. I couldn’t think of any dog poems that I loved, but here are some excerpts about one of my favourite fictional dogs, Montmorency from Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog).

“To look at Montmorency you would imagine that he was an angel sent upon the earth, for some reason withheld from mankind, in the shape of a small fox-terrier. There is a sort of Oh-what-a-wicked-world-this-is-and-how-I-wish-I-could-do-something-to-make-it-better-and-nobler expression about Montmorency that has been known to bring the tears into the eyes of pious old ladies and gentlemen.

When first he came to live at my expense, I never thought I should be able to get him to stop long. I used to sit down and look at him, as he sat on the rug and looked up at me, and think: ‘Oh, that dog will never live. He will be snatched up to the bright skies in a chariot, that is what will happen to him.’

But, when I had paid for about a dozen chickens that he had killed; and had dragged him, growling and kicking, by the scruff of his neck, out of a hundred and fourteen street fights; and had had a dead cat brought round for my inspection by an irate female, who called me a murderer; and had been summoned by the man next door but one for having a ferocious dog at large, that had kept him pinned up in his own tool-shed, afraid to venture his nose outside the door for over two hours on a cold night; and had learned that the gardener, unknown to myself, had won thirty shillings by backing him to kill rats against time, then I began to think that maybe they’d let him remain on earth for a bit longer, after all.”

When we first meet Montmorency, he is helping Jerome, Harris and George pack for their boating holiday, although the three men don’t always appreciate the dog’s assistance:

“Montmorency’s ambition in life is to get in the way and be sworn at. If he can squirm in anywhere where he particularly is not wanted, and be a perfect nuisance, and make people mad, and have things thrown at his head, then he feels his day has not been wasted.

To get somebody to stumble over him, and curse him steadily for an hour, is his highest aim and object; and, when he has succeeded in accomplishing this, his conceit becomes quite unbearable.

He came and sat down on things, just when they were wanted to be packed; and he laboured under the fixed belief that, whenever Harris or George reached out their hand for anything, it was his cold, damp nose that they wanted. He put his leg into the jam, and he worried the teaspoons, and he pretended that the lemons were rats, and got into the hamper and killed three of them before Harris could land him with the frying-pan.

Harris said I encouraged him. I didn’t encourage him. A dog like that don’t want any encouragement. It’s the natural, original sin that is born in him that makes him do things like that.”

Montmorency has quite a few adventures during their holiday, including an encounter with a tomcat:

“I like cats; Montmorency does not.

When I meet a cat, I say, ‘Poor Pussy!’ and stop down and tickle the side of its head; and the cat sticks up its tail in a rigid, cast-iron manner, arches its back, and wipes its nose up against my trousers; and all is gentleness and peace. When Montmorency meets a cat, the whole street knows about it; and there is enough bad language wasted in ten seconds to last an ordinarily respectable man all his life, with care.”

However, Montmorency has met his match with this particular Tom (“there was something about the look of that cat that might have chilled the heart of the boldest dog”). Montmorency also comes off the worst in an encounter with a kettle, but this doesn’t stop him helping with the cooking – for example, when the men decide to make an Irish stew:

However, Montmorency has met his match with this particular Tom (“there was something about the look of that cat that might have chilled the heart of the boldest dog”). Montmorency also comes off the worst in an encounter with a kettle, but this doesn’t stop him helping with the cooking – for example, when the men decide to make an Irish stew:

“Montmorency, who had evinced great interest in the proceedings throughout, strolled away with an earnest and thoughtful air, reappearing, a few minutes afterwards, with a dead water-rat in his mouth, which he evidently wished to present as his contribution to the dinner; whether in a sarcastic spirit, or with a genuine desire to assist, I cannot say.”

Montmorency may have begun the book by advising the men not to embark on their trip (“He never did care for the river, did Montmorency”), but he valiantly supports them throughout their travails, so it’s only fitting that he has the last word:

“‘Well,’ said Harris, reaching his hand out for his glass, ‘we have had a pleasant trip, and my hearty thanks for it to old Father Thames—but I think we did well to chuck it when we did. Here’s to Three Men well out of a Boat!’

And Montmorency, standing on his hind legs, before the window, peering out into the night, gave a short bark of decided concurrence with the toast.”

November 9, 2012

Puffins and Giant Squid and Portuguese Water Dogs

It seems to have turned into Animal Month here at Memoranda.

Firstly, I read a wonderful story about a birding enthusiast who re-established a breeding colony of Atlantic puffins on the tiny island of Montmaray Eastern Egg Rock, off the coast of Maine. Stephen Kress and his colleagues used wooden decoys, recorded bird calls and mirrors to entice puffins and terns to nest on the island, and these techniques have now been used to help “restore 49 seabird species in 14 countries, including some extremely endangered bird species”.

Then there was this story about Steve O’Shea, a marine biologist from New Zealand who is on a quest to capture (and breed) live giant squid, despite the many difficulties involved (for example, “accustomed to living in a borderless realm, a squid reacts poorly when placed in a tank, and will often plunge, kamikaze-style, into the walls, or cannibalize other squid”). I also enjoyed Sy Montgomery’s description of the intelligence and creativity of giant Pacific octopuses1, who often do not appreciate being captured and studied by humans (according to Montgomery, “Octopuses in captivity actually escape their watery enclosures with alarming frequency. While on the move, they have been discovered on carpets, along bookshelves, in a teapot, and inside the aquarium tanks of other fish—upon whom they have usually been dining.”)

Then there was this story about Steve O’Shea, a marine biologist from New Zealand who is on a quest to capture (and breed) live giant squid, despite the many difficulties involved (for example, “accustomed to living in a borderless realm, a squid reacts poorly when placed in a tank, and will often plunge, kamikaze-style, into the walls, or cannibalize other squid”). I also enjoyed Sy Montgomery’s description of the intelligence and creativity of giant Pacific octopuses1, who often do not appreciate being captured and studied by humans (according to Montgomery, “Octopuses in captivity actually escape their watery enclosures with alarming frequency. While on the move, they have been discovered on carpets, along bookshelves, in a teapot, and inside the aquarium tanks of other fish—upon whom they have usually been dining.”)

Finally, it was announced this week that the world’s most famous Portuguese water dog, Bo Obama, will remain in the White House for another four years. Well done, Bo.

_____

Yes, apparently it’s octopuses. My Oxford dictionary says that “the word octopus comes from Greek, and the Greek plural form is octopodes. Modern usage of octopodes is so infrequent that many people mistakenly create the erroneous plural form octopi, formed according to rules for Latin plurals”. ↩

November 4, 2012

Jubilate Agno by Christopher Smart

I am more of a dog person than a cat person, but I was completely charmed by Christopher Smart’s ode to his cat Jeoffry, when I first read it a few years ago. The Jeoffry verses are part of a much longer work, Jubilate Agno1, which was written sometime between 1759 and 1763. Christopher and Jeoffry were incarcerated at St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics at the time, which may account for what Robert Pinsky calls the “oddball, manic seriousness” of the poem.

Poor Christopher Smart died in a debtor’s prison a few years later, and Jubilate Agno was not published until 1939. Naturally, Rupert Stanley-Ross loved it and learned the Jeoffry section by heart, which is why he’s able to quote from it in The FitzOsbornes at War. There wasn’t room to quote the entire Jeoffry section in that book, so here it is, for those who are interested.

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For is this done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

For having done duty and received blessing he begins to consider himself.

For this he performs in ten degrees.

For first he looks upon his fore-paws to see if they are clean.

For secondly he kicks up behind to clear away there.

For thirdly he works it upon stretch with the fore paws extended.

For fourthly he sharpens his paws by wood.

For fifthly he washes himself.

For Sixthly he rolls upon wash.

For Seventhly he fleas himself, that he may not be interrupted upon the beat.

For Eighthly he rubs himself against a post.

For Ninthly he looks up for his instructions.

For Tenthly he goes in quest of food.

For having consider’d God and himself he will consider his neighbour.

For if he meets another cat he will kiss her in kindness.

For when he takes his prey he plays with it to give it chance.

For one mouse in seven escapes by his dallying.

For when his day’s work is done his business more properly begins.

For he keeps the Lord’s watch in the night against the adversary.

For he counteracts the powers of darkness by his electrical skin and glaring eyes.

For he counteracts the Devil, who is death, by brisking about the life

For in his morning orisons he loves the sun and the sun loves him.

For he is of the tribe of Tiger.

For the Cherub Cat is a term of the Angel Tiger.

For he has the subtlety and hissing of a serpent, which in goodness he suppresses.

For he will not do destruction, if he is well-fed, neither will he spit without provocation.

For he purrs in thankfulness, when God tells him he’s a good Cat.

For he is an instrument for the children to learn benevolence upon.

For every house is incompleat without him and a blessing is lacking in the spirit.

For the Lord commanded Moses concerning the cats at the departure of the Children of Israel from Egypt.

For every family had one cat at least in the bag.

For the English Cats are the best in Europe.

For he is the cleanest in the use of his fore-paws of any quadrupede.

For the dexterity of his defence is an instance of the love of God to him exceedingly.

For he is the quickest to his mark of any creature.

For he is tenacious of his point.

For he is a mixture of gravity and waggery.

For he knows that God is his Saviour.

For there is nothing sweeter than his peace when at rest.

For there is nothing brisker than his life when in motion.

For he is of the Lord’s poor and so indeed is he called by benevolence perpetually — Poor Jeoffry! poor Jeoffry! the rat has bit thy throat.

For I bless the name of the Lord Jesus that Jeoffry is better.

For the divine spirit comes about his body to sustain it in compleat cat.

For his tongue is exceeding pure so that it has in purity what it wants in musick.

For he is docile and can learn certain things.

For he can set up with gravity which is patience upon approbation.

For he can fetch and carry, which is patience in employment.

For he can jump over a stick which is patience upon proof positive.

For he can spraggle upon waggle at the word of command.

For he can jump from an eminence into his master’s bosom.

For he can catch the cork and toss it again.

For he is hated by the hypocrite and miser.

For the former is affraid of detection.

For the latter refuses the charge.

For he camels his back to bear the first notion of business.

For he is good to think on, if a man would express himself neatly.

For he made a great figure in Egypt for his signal services.

For he killed the Icneumon-rat very pernicious by land.

For his ears are so acute that they sting again.

For from this proceeds the passing quickness of his attention.

For by stroaking of him I have found out electricity.

For I perceived God’s light about him both wax and fire.

For the Electrical fire is the spiritual substance, which God sends from heaven to sustain the bodies both of man and beast.

For God has blessed him in the variety of his movements.

For, tho he cannot fly, he is an excellent clamberer.

For his motions upon the face of the earth are more than any other quadrupede.

For he can tread to all the measures upon the musick.

For he can swim for life.

For he can creep.

‘Six studies of a cat’ by Thomas Gainsborough, 1763–70

_____

The Jeoffry segment can be found in Fragment B, part 4. ↩