Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 2

January 14, 2025

Real People in Historical Fiction

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

In the Montmaray Journals series, there are a lot of real, historical people interacting with my made-up characters. This presented a bit of a challenge to me, as a writer. Firstly, I needed to know a LOT about the real people I’d decided to add to my story. I had to know what they looked like, how old they were, what their nicknames were, how they spoke, what their political beliefs were, who they hung out with . . . which meant doing lots of reading. If they (or their friends) had published their diaries or written their memoirs, I read those. I read biographies of them (most of them were really famous, so they each had at least one biography). I examined photographs of them and (in the case of Winston Churchill) listened to recordings of their speech. I read newspaper and magazine articles about them so I could get an idea of what other people at the time thought of them. I also needed to know exactly where they were at key points of my story (for example, I couldn’t have Sophie FitzOsborne meeting Kathleen Kennedy at an English house party if Kathleen was actually in New York at the time).

Even with all that information, I still had to make some things up, but I tried to keep it consistent with the known facts. For example, I don’t know for sure how John F. Kennedy would have reacted if he’d met fictional Veronica FitzOsborne at a cocktail party – but the facts of his life suggest he would have flirted with her, as he did with most beautiful women he encountered, and he’d probably have asked her out to dinner at some stage, so that’s what happens in The FitzOsbornes in Exile.

There is another problem with using real people in fiction. What if they don’t like what you’ve said about them? What if they sue you and your publisher for defamation, and your books get removed from bookshops and destroyed? (Yes, this has actually happened to some Australian authors.) However, people can’t sue for defamation if they’re dead, and luckily for me, nearly all the real people in the Montmaray Journals died a long time ago. I think the only real people in the books who are still alive1 are the Queen (see photo of her above, aged about thirteen, with her little sister, Princess Margaret, and her grandmother, Queen Mary) and the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, and I’m pretty sure that neither of them has read any of my books (especially as the books aren’t published in the UK). In any case, these two people are only mentioned in passing and I don’t say anything bad about them. They might not like what I wrote about their relatives (such as Princess Margaret and Diana Mosley), but a) their relatives are dead and b) anything I wrote about their relatives was based on previously published information and I kept a record of all my sources. Even so, I checked with my editor and she checked with the legal department at her publishing house. Publishers take this sort of thing very seriously.

If you were writing a story with real people in it – which real people would you use?

Next: Why the Australian and North American editions of my books are different

They were alive when I originally wrote this blog post, but Queen Elizabeth II died in 2022 and Deborah, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, died in 2014. ↩January 13, 2025

Planning Vs Not Planning

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

In my earlier posts, I talked about the detailed planning I did when writing The FitzOsbornes at War. I just want to emphasise that this is NOT THE ONLY WAY TO WRITE A NOVEL. It’s not even the only way I write novels. For my first book, I did ZERO planning. I had no idea how to write a novel, so I just sat down and started typing scenes, which turned into chapters. Eventually, I had a lot of words. Most of them were rubbish. I threw out a lot, kept the bits I liked and started typing again. This draft was a bit better. I kept doing this for another seven drafts. Eventually I had a book.

I decided to plan my next book, A Brief History of Montmaray, because it was told in the form of journal entries, with dates, and I wanted to incorporate a lot of real historical events into my story. For me, the only way I could keep everything straight in my head was to use index cards. When I was writing the next two Montmaray books, I refined my system a little (for example, I learned that writing down page references for the sources I was using saved me a lot of time and frustration).

For the book I’m working on now, I’m still using my planning system, even though the book isn’t told in journal form. It does have a lot of historical research in it, though, so I think my system will help me keep track of what I’m doing.

But (and I finally get to the point of this blog post), writers have their own individual ways of doing things. Each writer, and each writing project, is unique. If you’re a writer, don’t let anyone (not even teachers; not even writing teachers) tell you there’s only one way to write. There isn’t! You can plan, or you can jump straight into writing without any planning. You can edit as you go, or you can leave the editing until you have a complete draft. It’s entirely up to you. The great thing is that it doesn’t matter how you do it. All that matters is what you end up with.

How do you write? Are you a planner or a non-planner?

You might also be interested in reading:

‘Save the Cat! Writes a Novel’ by Jessica Brody

‘Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life’ by Anne Lamott

‘On Writing’ by Stephen King

Next: Real People in Historical Fiction

January 12, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step Seven

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

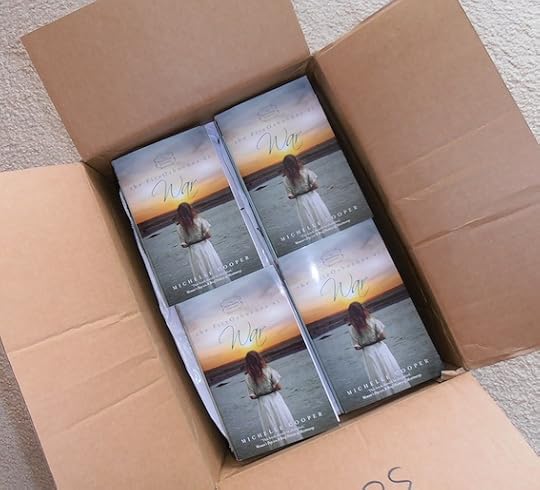

7. Admire Your Finished Book

Okay, this is the only step to writing a historical novel that is ACTUALLY easy. I may not have been totally accurate when I said you could write a historical novel in seven EASY steps. But hey, I’m a novelist. I’m allowed to make up some things.

Anyway, after this step, there are many other things that go on, to do with sales and marketing and publicity, so that people will actually buy the book. I’m not really an expert in any of that, but if you want to ask a question, leave a comment below and if I can’t answer it myself, I’ll see if I can find someone who does.

Next: Planning vs Not Planning

January 11, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step Six

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

6. Gaze Upon the Efforts of the Designer and Typesetter

This is one of the easiest stages for authors, because it mostly consists of us watching other people work really hard.

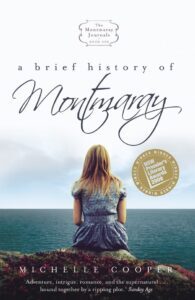

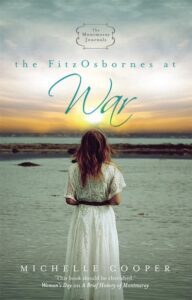

Firstly, there’s the cover design to admire. In the case of the Australian edition of The FitzOsbornes at War, the designer had already come up with beautiful designs for the first two books in the Montmaray Journals series, which looked like this:

NOT that creating those two covers was a quick and easy process. The designer came up with FOURTEEN possible covers for the first two books. Some were hand-drawn portraits, some were based on photos. Each had its own individual design for the title of the book, the title of the series and the author name. Then a lot of people at Random House Australia sat down to discuss which covers would best show what the book was about and would most appeal to readers. I also added my opinions, and my publishers were polite enough to listen (in general, authors don’t get much say in how their book covers look). Then my editor wrote the blurb on the back, and organised for legal permission to use the photographs, and looked for some flattering review quotes to add to the cover.

By the way, all the cover photographs for the Australian editions of The Montmaray Journals were taken by an extremely talented teenager, Nikoline Rasmussen.

Anyhow, as you can see, the third book cover used the same model as the first two books, with a different background. The cover designer made some changes to the original photograph to add colour to the sky, so that it would look a bit more cheerful (and, as it happens, to fit a scene in the book more closely). If you click on the Nikoline Rasmussen link above, you’ll also see the original photograph that was used for the cover of A Brief History of Montmaray. (And if you’ve read the book, you can probably figure out why the cover designer made some changes to the image.)

Meanwhile, the typesetters had turned my Word document into five hundred pages of typeset book pages, using a special font and chapter heading designs to match the first two books in the series. But mistakes happen during typesetting. There are weird typos. The spacing looks wrong in some places. And authors, being the contrary creatures they are, often have last-minute changes they need to make. (Especially when they’ve just finished copy-editing the American edition of their book and their American copy-editor has pointed out a glaring historical error. Cough. Not that that would happen to me or anything.)

This is why proofreading is really important. In the case of The FitzOsbornes at War, the typeset pages (called proofs, or galleys, or first pages, depending on whom you ask) were read by a proofreader who hadn’t seen the manuscript, plus an editor who was familiar with the first two books, as well as by myself. (You can see a tiny section of my typeset manuscript below, with some of my corrections.) Then my editor had a long meeting with me at the Random House Sydney office and we went through all the combined changes and argued about commas again. But it was polite arguing.

By the way, if you’ve heard about ‘ARCs’ (or ‘bound proofs’ or ‘galleys’) and wondered what they are – they’re the typeset pages bound into book form, with a rough version of the cover art. That is, they are the book BEFORE it’s been proofread, complete with weird typos, factual errors, etc. So if you read an ARC, you’re not reading the final book. You’re reading a very early, flawed version of the book. ARCs are only printed so that people reviewing the book can read it and write their review before the book is published – although they need to check the final version of the book if they’re going to use quotes from the book or complain about ‘errors’ in the book.

Next: The finished book

January 10, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step Five

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

5. Edit, Edit, Edit

I tend to edit as I write. (This may be why I’m the slowest writer in the universe.) I started each day of writing by looking over the previous day’s work and making whatever changes were necessary. Sometimes, this meant going back even further, to previous chapters. My months of planning, plus my rewrite-as-I-go strategy, meant that by the time I finished the ‘first draft’ of The FitzOsbornes at War, the manuscript looked okay. It was nowhere near perfect, but it was pretty close to the final shape of the novel. I checked my facts and corrected any spelling and grammar errors I could find. Then I sent the whole thing off to my two editors, one in Sydney and one in New York, and told them to be ruthless with it.

They were.

But they were also very tactful. The editors I’ve worked with have all been super nice and very good at their jobs. They tend to use the sandwich method when they give feedback – that is, they sandwich their harshest criticisms in thick slabs of praise, so it’s easy to digest.

When I get an editing letter from them, it usually says something like this:

“This is your BEST BOOK EVER. I love it! Here are some of the things I loved about it [insert half a page of examples of clever/funny things that they found in manuscript].

Now, there are just a few tiny things we think you could change to make this book even more perfect [insert five pages of things that didn’t work so well, with suggestions for fixing them]

Overall, though, you are a genius writer! This book is going to be brilliant!!!”

Don’t you wish teachers would give that sort of feedback on assignments? (Maybe your teachers do. Mine didn’t.)

Here are examples of things my editors said about The FitzOsbornes at War manuscript:

“Could you explain in more detail about Toby’s plan to [do mysterious thing]?”

and

“It would be good if there was a scene that actually SHOWED Sophie [doing important thing], instead of her merely talking about it, three months later.”

and

“It’s great that Toby tells Sophie all about [shockingly awful thing], but how come she never mentions it in her journal ever again?”

I tend to agree wholeheartedly with about 90% of my editors’ suggestions. A further 5% has me going, “Mmm, you’ve got a point about that, but if I change it, then this part won’t make sense . . .” In those cases, I usually come up with some sort of compromise solution. Then there’s another 5% where I put my foot down and say, “NO WAY am I changing that!” (I say this in my head. My editors aren’t actually there when I’m rewriting the manuscript. Thank goodness.)

The sort of editing I’ve talked about so far is usually called the structural edit. It’s about fixing the plot so that the story makes sense. The next stage is the copy edit, which looks at individual words and sentences, checks facts, ensures spellings are consistent throughout the series, that sort of thing. (We tend to argue about commas A LOT at this stage.) In practice, the structural and copy editing blurred together a bit for The FitzOsbornes at War. Finally, the editing was done and the whole thing was sent off to the typesetters.

Next: Book design and typesetting

January 9, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step Four

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

4. Write Lots of Words

In the case of The FitzOsbornes at War, I had to write about 136,000 words. Luckily, I didn’t know how ridiculously long the story was going to be when I started typing, otherwise I’d have been too intimidated even to begin the book. As it was, I simply sat down at my computer every day, looked at my stack of index cards and told myself, ‘Okay. Today, I’ll try to get through two cards.’ Then, after I incorporated each bit of information from an index card into my story, I’d put a tick next to the information on the card (as you can see in yesterday’s index card photo). It was very satisfying to end a day with a couple of ticks, but that didn’t happen very often. Sometimes it would take me weeks to get through a single card. Sometimes I’d decide that a particular fascinating fact was never going to fit comfortably into my story, no matter what I did. Regardless, I plodded on.

I wrote the book in its correct order, from the first chapter to the last, so I wouldn’t get confused. This also helped motivate me (‘Okay, today I have to write that boring yet necessary bit about Churchill, but as soon as that’s done, I get to write that funny story about Henry!’). Yes, writers are weird.

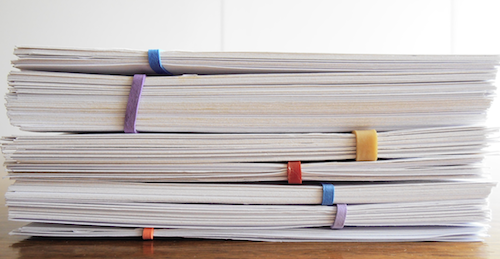

After about a year and a half, I had a whole lot of words printed on paper:

Don’t even ask how many pages that is. TOO MANY. That’s why it needed to be edited.

Next: Editing

January 8, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step Three

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

3. Get Organised

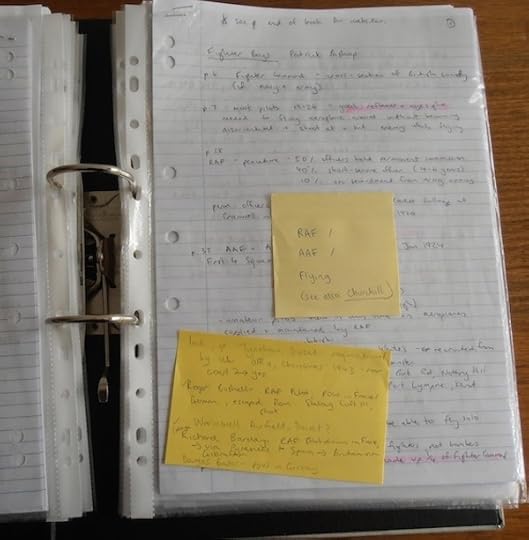

As I researched, I took notes and I filed all my bits of paper in a big folder:

How did writers function before Post-It notes were invented? I used Post-Its as bookmarks, to label sections of my notes and to jot down bits of information that might come in handy later. As I was reading, I was constantly on the lookout for interesting trivia, funny anecdotes, outrageous people – anything that I could fit into my own story.

After about six months, my notes had outgrown my folder and my brain was about to explode with all my ideas, which meant it was time to move onto my index cards:

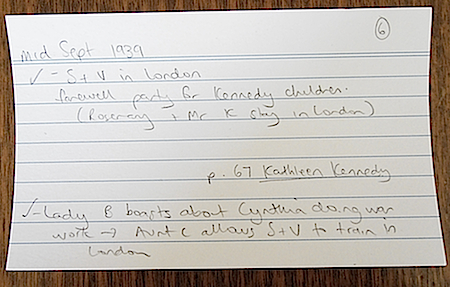

For The FitzOsbornes at War, I ended up with about two hundred palm-sized cards, each one containing notes about an important event of the war and/or a significant event for one of my characters. Each card also had a date at the top, and a number that showed where the card fitted into the storyline, as well as page references for my sources of information. For example, here’s card number 6:

If you can’t read my writing (and I don’t blame you if you can’t – even I have trouble reading it sometimes), it says, “mid Sept 1939 – S + V in London, farewell party for Kennedy children (Rosemary + Mr K stay in London) p. 67 Kathleen Kennedy – Lady B boasts about Cynthia doing war work –> Aunt C allows S + V to train in London”.

This tells me that in an early chapter, I need to move my two main characters, Sophie and Veronica, to London, re-introduce my readers to the Kennedy family and explain why Kathleen Kennedy leaves England. I also need to explain why their strict guardian, Aunt Charlotte, allows Sophie and Veronica to stay in London by themselves. And if I need to check any facts about this, I should look on page 67 of Kathleen Kennedy’s biography.

Organising all two hundred cards into some sort of logical order gave me a big, big headache, but when it was done, I could finally start writing. Yay!

Next: The actual writing bit

January 7, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step Two

First published on the Centre for Youth Literature Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012.

2. Do Lots of Research

The problem with doing research for a historical novel is that you don’t know what you need to know until you’ve actually finished writing the book. All you can do at the start is read as widely as possible. In my case, I began by reading general histories of the Second World War.

As you can see from my bookcase, I read about life in England during the war, and then started reading biographies and memoirs of significant people, including Winston Churchill (wartime Prime Minister), Kathleen Kennedy (yes, one of those Kennedys), Samuel Hoare (Ambassador to Spain) and Oswald Mosley (British Fascist). Then I searched the internet for newspaper articles, photos, film clips and other useful bits of information. It was like doing an enormous school assignment, but a lot more fun, because it was a topic that fascinated me AND I got to set my own questions.

The more I read, the more interesting story ideas popped into my head – which meant I needed to do even more research to find out whether those story ideas would fit into the real events of the war. I wasn’t writing a history textbook, but I did want to get the facts right. Unfortunately, even trying to find out something as simple as when a particular battle ended could turn up five different answers. Was it the day the first group of soldiers waved a white flag? Was it the next day, when their commanding officer ordered his men to lay down their arms, even though some of them kept on fighting? Was it the day a formal statement of surrender was signed on the battlefield? You get the idea.

I also needed to work out which sources were reliable. I found that books, newspaper articles and diaries written during the war were more likely to be biased, confusing and full of half-truths (or even flat-out lies) than later accounts of the war. This was partly because wartime censorship laws and military regulations made it impossible for people to write the truth while the war was happening. It wasn’t until the 1970s, for example, that the people who’d decrypted German codes at Bletchley Park were allowed to talk about their experiences. Ordinary civilians in wartime, relying on censored newspapers and radio broadcasts for their ‘facts’, often hadn’t a clue what was really going on in the wider world.

But even the Very Important People who DID know what was going on behind the scenes, and who wrote their memoirs AFTER the war, could still be unhelpful and unreliable. For example, one part of my plot involved a real event in Spain, in which the Nazis tried to kidnap a particular member of the British royal family. I’d read one version of the event, but I figured the memoirs of Sir Samuel Hoare, British Ambassador to Spain during the war, would be full of useful details. His book had never been published in Australia and was long out of print, but eventually I tracked down a second-hand copy in Adelaide via the internet. And when I read it, it turned out to be ABSOLUTELY HOPELESS. Not only did he fail to mention the kidnapping plot, he wrote a lot of self-important rubbish about what a wonderful Ambassador he’d been and how he’d single-handedly stopped Spain from helping the Nazis, which was TOTALLY NOT TRUE.

So, despite teachers often saying that books are more reliable than the internet, this is not always the case. For instance, I found lots of useful information on blogs and in official online archives when I was searching for details about fighter pilots in the Royal Air Force. The internet also came in handy when I needed to check lines of poetry or find out when particular newspaper articles had been published. It was all SO much easier than having to trek off to the library, which is what writers had to do in the Olden Days. Hooray for the internet!

Next: Getting all this research organised

January 6, 2025

How To Write A Historical Novel In Seven Easy Steps – Step One

First published on the YA Literature website, Inside A Dog, in 2012. An excerpt from the original introduction:

…I’m going to be blogging about the process of writing The FitzOsbornes at War. I’ll also talk about some interesting facts I learned about wartime England. For instance, did you know that street lights and car headlights were blacked out to deter Nazi bombers, so pedestrians were advised to carry ‘a small white dog, such as a Pekinese’ at night? (I still don’t understand how that would be helpful, unless you’d dipped your Pekinese in fluorescent paint.) And did you know that the British government even had laws about how many buttons, pleats and pockets that clothes could have? All this and more will be discussed this month…

More information here: I’m Back.

1. Think Up A Good Idea For A Story

This was pretty easy for The FitzOsbornes at War, because it was the last book in the series and I’d already figured out how the whole story would end. But in general, my books begin with a character, a setting (a place and a time) and a problem. Usually the problem grows out of the setting. For example, The FitzOsbornes at War starts with the main characters sitting in their English country mansion and listening to the radio, on the third of September, 1939. Which just happens to be the day that the British Prime Minister declared war on Nazi Germany.

War, by definition, is full of conflict, so it provides lots of potential for a story. But this particular war was especially useful for my story, because the FitzOsbornes really, really hate the Nazis (due to things that happened in Books One and Two). This war would be a chance for them to have their revenge for the past, and maybe even regain their lost kingdom. The FitzOsbornes wouldn’t be sitting on the sidelines of the war, watching with mild interest – they’d be desperate to throw themselves into the battle. (Well, some of the characters would be more desperate than others. Yes, Henry FitzOsborne, I’m looking at you.)

The next stage is thinking about the individual characters and their own personal problems. For each main character in The FitzOsbornes at War, I needed to consider what he or she wanted most of all in life. Love? Power? Knowledge? Revenge? How would they try to gain these things? What obstacles could I toss in their paths to make them stumble? Would they actually achieve their goals in the end? Would they give up halfway there, having realised their goal was unachievable? Would they die? (I already knew one of the FitzOsbornes was not going to survive the war. I wanted to write about how terrible and destructive and wasteful war is, so I knew I had to sacrifice at least one beloved character.) But to answer all these questions in detail, I needed to know a lot more about what actually happened during the Second World War.

Next: Researching a historical novel

I’m Back

It wasn’t any deliberate decision on my part, but it’s been almost a year since I’ve posted anything on Memoranda. I’ve been busy with Day Job and various other activities, including starting work on a completely new novel1. I’ve been reading a lot, but each time I sat down to share my opinion of a book, I thought, ‘Does anyone need to know this? Why would they care what I think? The author of this bestselling book is doing just fine without my recommendation.’ And then I’d wander off to do something else.

I’m not certain what I’ll be doing with Memoranda this year, but I’d like to keep it going, if only because it’s the closest thing I have to a social media presence now that BookTwitter is dead. Where are all the readers, authors, publishers and agents now? Facebook? Instagram? TikTok? None of those options appeals to me. Am I meant to join Bluesky? I do have an account at Substack so I can read posts there, but have zero interest in posting my own Substack pieces. Readers and writers—where are you hanging out now?

Anyway, while I’m figuring this out (and also to remind myself of how WordPress works), this month I’ll be re-posting a blog series written back in 2012 when I was Writer in Residence at Inside A Dog, the website of the Melbourne-based Centre for Youth Literature. Sadly, the Centre for Youth Literature was shut down five years ago after it lost government funding, which meant the demise of not just Inside A Dog and its archives, but The Inky Youth Literature Awards and Reading Matters, an excellent biennial conference that hosted YA authors from all over the world. This blog series was written when The FitzOsbornes at War was released in Australia and it’s aimed at teenage readers, a behind-the-scenes look at writing historical fiction. Unfortunately, I can’t re-post all of the great discussion that appeared in the comments of the original posts, but feel free to add your own comments.

Next: How to write a historical novel in seven easy steps

I’m not going to talk about this yet, because I don’t want to jinx it. But it’s been an absolute joy to work on so far. ↩