Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 5

December 29, 2020

‘The Cricket Term’, Part Four

Chapter Six: Letter From Home

The next cricket match is against Ginty’s team, Lower V.A, who’ve been coached by Evil Lois and are feeling very confident. But Lower IV.A field, bowl and wicket-keep very effectively, aided by Nicola’s insider knowledge of Ginty’s batting weak spots to get Ginty out for one measly run. Lower IV.A struggle a bit when it’s their turn to bat, but a last-minute effort by Barbara and Pomona, combined with Lower V.A’s pathetic fielding, win the day. Pomona really is a solid player. Nicola should have played her earlier. (I say, with my near non-existent cricketing expertise – I had to Google how many balls were in an over. I really don’t know how Americans would manage to follow all the details in this book’s cricket descriptions.)

Then there’s an excellent scene where Miss Craven and Janice are watching Nicola coach the team, noting how well Nicola is doing. Evil Lois is nearby training Lower V.B, while Janice wonders to herself whether Lois is really only helping the teams playing against Nicola, which sounds demented, “except that Lois was a demented character”. When Lois joins them, she’s horrified to hear Miss Craven suggest that Nicola will be Games Captain in a few years. Lois blusters about Nicola’s team doing too much practice and how they should be stopped because it’s not fair to the other teams, which Miss Craven thinks is “the most absurd argument I’ve heard in a very long time” and also, why has Lois stopped Nicola’s team from using the good nets and pitches for practice? Furthermore, if Lower IV.A lose their next match, Miss Craven wants to put Nicola on the ‘Prospects’ list, where she’ll get special coaching and be considered for the school team. Janice, stirring like mad, says that would be fantastic for Nicola, when not “even Rowan managed it that young” and then adds pointedly, “It should almost make up for that—misunderstanding—over the netball team.” Which Miss Craven agrees with, saying it was most uncharacteristic of Nicola to be unreliable, so she should ask Nicola about what really happened at some stage. And Lois leaves, deeply unsettled.

I love Janice.

I love her even more in the next scene, because she’s the only good thing about the situation. Poor Nicola gets an ominous-looking letter from her mother, so she goes up to the roof to read it in private, worrying that Buster or Tessa have died. But it’s terrible in an unexpected way — Mrs Marlow has written to say the school fees are going up, so one of the sisters will have to leave Kingscote and it has to be Nicola. It can’t be Ann or Ginty because they’re about to do O and A levels, and it can’t be Lawrie, because she’s so immature that she needs boarding school to make her grow up. Both Marlow parents agree it should be Nicola because “you’re a sensible person who won’t stamp around, spoiling things for yourself … complaining for years it was all dreadfully unfair.” Nicola will go to Colebridge Grammar, which must be an okay school because Edwin’s sending Rose there. And she mustn’t talk about this with anyone.

My previously low opinion of the Marlow parents has plummeted to uncharted depths.

I mean, REALLY? Mrs Marlow sells their diamonds and spends it on fancy hunting horses, but now they can’t afford school fees? They’ve inherited a huge estate, but they can’t rent it out to earn money because Captain Marlow wants to swan about being Lord of the Manor, with Rowan forced to run the farm for no pay. They chose to have EIGHT children and send them all to expensive private boarding schools, without thinking how they’d afford it all the way through their schooling. There’s no mention of taking Peter out of his naval cadet school, even though he hates it and has no intention of ever joining the navy. And they don’t decide to send all four girls to Colebridge Grammar, where at least they’ll have each other — no, just poor Nicola by herself, not knowing anyone. And Nicola’s the one who really loves Kingscote, has lots of friends, is doing well academically, showing good leadership skills, and instead of being rewarded for this, she’s punished.

Fortunately, Janice is there to offer unsentimental, practical support (and barley sugar). Jan also notes that now that Karen has left Oxford, her Prosser scholarship can be awarded to someone else, and maybe, if Nicola works a bit harder, she could win that and stay at Kingscote. Nicola’s only real rivals are Miranda, who definitely doesn’t need the money because her father’s just paid for the school swimming pool, and Meg Hopkins. So there’s a bit of hope.

Unfortunately, Nicola has been so distressed that she’s missed first period English with their inept student teacher, who is told by the girls that the correct procedure is for them all to go outside and look for Nicola. This is a welcome bit of comic relief, as Lower IV.A “prance about the grounds, looking under dock leaves and turning stones”, doing Nymph dances in the middle of the playing field. Unfortunately, Miss Cromwell happens to look out the window and see this and there is blood for breakfast. They get a form conduct mark, so they’re out of running for the Form Shield for the third year in a row, and they have compulsory silence till Sunday, which Nicola doesn’t mind because at least no one will ask why she’d been so upset.

Chapter Seven: Dolphins and Nemesis

Ginty is still a bit miffed that she’s not in the school play, but thanks to all the extra practice and her lucky four-leaf clover, she and Monica are chosen for the swimming and diving match against the Wade Abbas Collegiate, which I guess is a girls’ school attached to the Abbey.

Meanwhile, Lawrie is having trouble with her Ariel role, because she just can’t imagine herself as a “fairy”. Miss Kempe attempts to explain that Ariel isn’t some twee fairy, but a near immortal, soul-less being with magic powers and suggests Lawrie read Lord of the Rings. But Lawrie continues to be terrible in the role.

Nicola reflects to herself that at least when she leaves Kingscote, there’ll be no annoying Ann or Lawrie around. Even Tim despairs of Lawrie. Tim’s also not making much progress on her costume design, although she has a good cathartic laugh with Nicola when they contemplate Ariel wearing briefer-than-briefs with glitter, in relation to Miss Keith. Then there’s a good conversation between Nicola, Tim, Miranda and Esther about what they might do in future. Tim has her sights on producing St Joan when they’re in Sixth Form and then becoming a real-life producer. Miranda will end up working in her father’s antiques shop, but wishes she had more of a choice – although she doesn’t really know what she wants to do, probably something in art and design. (I’m surprised Miranda isn’t aiming for Oxford and something more academic, as she seems very intelligent and curious about the world.) Nicola usually tells people she wants to join the Wrens, but unfortunately, she knows she’ll never get to command a ship because she’s not a boy. She tells the others she’s planning to sail solo round the world, then decide about her future. Esther, unexpectedly, wants to be a gardener and live in her own flat with Daks. Good for her.

Then there are some more cricket matches. Upper V.B, the favourites, annihilate the poor little Seconds, in a very unfair and humiliating display of dominance, so the whole school turns against them. Meanwhile, the Sixth Form team, which includes Lois and Janice, beat Middle Remove, who had already won against Upper V.A. (“a bunch of intellectuals who could have beaten them easily enough, but had decided that passing their numerous O levels creditably took precedence” and therefore played to lose, to Ann’s dismay). This means that the entire school, including Nicola and Miranda, turn up to cheer the Sixth when they play those rotten scoundrels, Upper V.B. The Sixth, encouraged by the wild applause, play well, and Janice is a batting star, and they win. So I think that means Nicola’s team will be playing Lois and Janice and the other sixth formers in the final, if they first manage to beat Lower V.B.

I am still mad at the Marlow parents.

Next, Chapter Eight: Casualty

December 28, 2020

‘The Cricket Term’, Part Three

Chapter Four: Assorted Disappointments

I’m so confused by the timeline of these books, even allowing for the time travelling that allows decades to pass between one school year and the next. I’d assumed that this book was set in the first term of the school year because they’d just had a long, eventful holiday, but I think it’s actually the last term, because Jan is about to finish school. So does that mean this term runs from about April to June, and the holidays in which Karen got married were actually the Easter holidays, not the summer holidays? But wasn’t The Thuggery Affair set in those Easter holidays, when Nicola was staying with Miranda in London? Or maybe that was half-term, not Easter? Maybe I should just not think about this too hard.

Much like Hogwarts, the number of students in the form seems to change according to plot requirements. For my own reference, here are the students in Nicola’s form, Lower IV.A, whose form teacher is Miss Cromwell:

Nicola Marlow, Games Captain

Lawrie Marlow, in some danger of being demoted to Upper IV.B next school year

Thalia (Tim) Keith

Miranda West

Esther Frewen, Stationery Monitor

Sarah (Sally), Form Prefect

Jean Baker, Form Prefect, dim but kind, used to sit next to Lawrie at the back of the classroom

Linda Stratton, now sits next to Nicola, will probably be demoted to Upper IV.B next year

Barbara (Barby) Wateridge, Door Monitress

Marie Dobson, currently has COVID, I mean “a feverish cold”, so not back at school yet

Pomona (Pippin) Todd

Elizabeth (Liz) Collins, used to be in Third Remove with the twins

Margaret (Meg) Hopkins, shy but gets high marks, friend of Berenice

Berenice Anderson, good at cricket but Nicola doesn’t like her much

Rosemary Wright, will probably go into Upper IV.B

Elaine Rees, another probable Upper IV.B

Margaret Sutton, another probable Upper IV.B

There may be other, unnamed students. I wonder what happened to Jenny Cardigan? I liked her name. We don’t find out who is Flower Monitor or Tidiness Monitor this term.

So, due to flu last term, they have school on Saturday mornings, half-term break is cancelled and all outings are banned. Sounds like a great way to create exhausted, demoralised, rebellious students. Miss Cromwell is as strict as ever, but it’s revealed “no actual harm came of standing up to Crommie every now and then” and she does occasionally exhibit signs of a sense of humour.

Pomona has been moved up to Lower IV.A from the B form and Miss Cromwell accidentally announces it in a way that allows Tim to be mean about Pomona’s weight. Fortunately, many of the other girls, including Nicola, think that Pomona is “much improved” since her tantrum-throwing Third Remove days, so hopefully she’s not being bullied as much as she used to be.

Miss Cromwell then orders Nicola to go and see Miss Kempe, who’s in charge of the play, but when Nicola finally tracks the teacher down, Miss Kempe assumes she’s Lawrie:

“I am Nicola, actually,” said Nicola apologetically.

“Are you now? Yes, perhaps you are, after all…”

Miss Cromwell also wants all the staff to know about the twins’ new seating arrangements in class – maybe the identical twins thing is going to be an important plot point again.

The Kempe meeting is just about how to manage Nicola singing Ariel’s songs, but does confirm that Lawrie will be Ariel, full stop. (Lawrie remains convinced she’s Ariel, question mark.)

Nicola is, predictably, taking her Games Captain role very seriously, or as Tim tells her, “doing your Marlow thing … being very very competent and very very keen.” Nicola has booked the cricket nets and pitch for practice every evening, but someone has been crossing out her name on the list. Is it Tim? No, Tim is so uninterested in cricket that she doesn’t even know they use nets. Of course, it’s Evil Lois, who stalks up and announces that lower forms are only allowed the terrible pitch behind the Pavilion and only twice a week. After she’s gone, Tim suggests that maybe, Lois is doing this behind Miss Craven’s back. Tim admits that Lawrie has told her the whole story about Lois lying and getting the twins in trouble at Guides and then throwing Nicola out of the netball team. Nicola is shocked by Lawrie’s inability to keep a secret (really? it’s Lawrie, for heaven’s sake) and Tim is amazed at Nicola’s refusal to tell Miranda or anyone else while Lois is still at school.

“You mean it might get around and she’d be clobbered? Why on earth should you mind that? You don’t even like her.”

But Nicola is being all noble and stiff-upper-lip and Marlowish about Lois. Nicola does have the good idea of having cricket practice early in the morning, before breakfast, so take that, Lois. Meanwhile, Tim is trying to design Tempest costumes and thinks about painting “real” magic signs on Prospero’s cloak, to Nicola’s alarm, because it might raise real demons – although on the positive and hilarious side, the demon might carry off Val Longstreet, their useless Head Girl. It’s nice to see Nicola and Tim getting along for a change.

Then the cast list goes up for The Tempest:

Prospero – Janice!

Miranda – Rachel Wilmot, understudy Naomi Lane

Caliban – Geraldine Hume

Ferdinand – Honor Seton

Ariel – Lawrie, understudy Miranda

Ariel singer/doppelgänger – Nicola, understudy Helen Bagshaw

Antonio – Denise Fenton, understudy Victoria Taylor

Juno – Elisabeth (Isa) Cardigan (Jenny Cardigan’s sister! Is A Cardigan!)

Reapers – Morris Group

Mariners – Emma Hillary, Monica

Nymphs – Natalie Hart, Eve Price and others who learn ballet

Strange Shape! – Pomona!

Ginty, who deliberately didn’t try in her audition, is devastated that she’s nothing, not even a Strange Shape. Her five friends, including Monica, are all in it and are surprised she isn’t even a nymph, but then one points out that the Marlows dominated the Christmas Play and really, she’s lucky to have extra time for swimming practice. And then Ginty pulls a four-leaf clover out of the lawn and then Monica bravely goes to Miss Kempe to say she wants out of the play. Ginty really is lucky: “it was fantastic to be the sort of person for whom others leapt to sacrifice themselves.” Ginty is a bit like Lawrie, awful but realistic.

Chapter Five: Postcard from Home

A short chapter in which two things happen.

Firstly, Nicola finishes reading The Mask of Apollo, but then Rowan sends a postcard reminding her to send it back to the library because it’s overdue and Miss Cromwell finds out about Nicola having an illegal book. Nicola admits committing this Mortal Sin and explains why she liked the book so much and Miss Cromwell is sympathetic, perhaps because Nicola has been doing so well at her schoolwork lately. Nicola says she thinks it was only breaking a regulation, but Cromwell says,

“Four hundred people living check by jowl need regulations, if only to protect the weak from the bullies and the foolish from their folly.”

(I haven’t noticed much protection from bullies for poor drippy Marie, and the teachers have been responsible for plenty of folly so far.)

Then Miss Cromwell asks Nicola why the book was limited to senior students and Nicola says it’s possibly “Because Nico liked men better than women, you mean?” (Oh Nicola, just wait till you read The Charioteer.) Her punishment is to read a long list of Cromwell-approved books, including Dickens and Sir Walter Scott, which really is a punishment.

The second thing is that all the early morning cricket practice pays off and in the first round of the tournament, Lower IV.A thrash Upper IV.B in less than forty minutes, with Esther bowling someone out, Pomona being a reliable wicket keeper, and Sally and Miranda making a good batting partnership. Evil Lois watches with feigned nonchalance, then slithers away, ha ha.

Next, Chapter Six: Letter from Home

December 27, 2020

‘The Cricket Term’, Part Two

Chapter Three: —And Away

Back at Trennels now and Esther is joyfully reunited with Daks. She asks Nicola if it was “your sister Karen in the paper who got married” and Nicola has to take “time and a moderate amount of skill” to answer Esther’s polite questions about “that near-disaster”. Why is it a near disaster? How was the disaster averted? I’m going to have to read that book, aren’t I?

Daks also kills Nicola’s hat, which Esther, always worried about rules, frets about. Nicola calms her down, while wondering “whether she wouldn’t find Esther’s panics a touch irritating if her face weren’t so fascinating”. I seem to remember Patrick also noticing Esther’s beauty and of course, his girlfriend is Ginty, the prettiest of the Marlow sisters.

Speaking of Ginty, she’s been learning Miranda’s lines from The Tempest, so I guess that’s the school play this term. Ginty had spent the holidays rehearsing her lines with Patrick and he had read the most romantic lines “rather well: she only wished she could be sure he meant them as Patrick”. Hmm, perhaps Ginty is more enthusiastic about their relationship than Patrick is? Ginty’s sensible, no-nonsense friend Monica arrives as the sisters are unpacking and she persuades Ginty not to audition too well for the play, so they can both concentrate on swimming and diving this term. Ginty immediately agrees and goes off with Monica to the pool, and Nicola observes disapprovingly that Ginty is as changeable as a chameleon. But perhaps Ginty’s just more socially aware and eager to fit in with others? It’s not necessarily a bad thing to care about others’ opinions, unless you’re a Marlow and believe yourself superior to everyone else.

Ann has unpacked for Ginty and Lawrie, and when Nicola tells her to stop it, Ann incoherently objects (“mainly from lack of practice—she so seldom sprang to her own defence”). She becomes totally flustered when Nicola mentions Ann is a dead cert to be Head Girl so she should practise being self-assertive. Nicola wonders why Ann is “so soft” only with her family, because Ann’s a bossy, competent Guide leader at school with the other girls. I wonder about that, too. Perhaps Ann is aware her siblings dislike her, so she tries extra hard to ‘help’ them, to try to change their opinion? They all seem to take advantage of her when it suits them, however much they complain about her behind her back. Poor Ann, she needs to leave home and go somewhere she can be useful and valued. Did I read in an earlier book that she wants to be a nurse, or am I misremembering?

Nicola runs into Tim, who is still Lawrie’s Best Friend Forever and Nicola’s Frenemy. Tim has a new spiky hairdo to match her personality. They go off to look at the noticeboards, where there is predictable chaos about the casting of the play. Lawrie is Ariel, but wants to be Caliban. Miranda West seems to be one of Lawrie’s understudies. Tim is nothing, but wants to be Assistant Stage Manager and work her way up rapidly to Producer, so puts her name down for Costumes and Props with Miss Jennings, the cool Art teacher. Nicola and Esther are Ariel singers, even though poor Esther has debilitating stage fright.

Then Miranda turns up and takes Nicola up a fire escape ladder to the roof, which seems a bit dangerous to be left open and accessible, but that’s Kingscote for you. Miranda spent her holidays in Greece and Palestine, lucky thing, and Nicola tells her best friend a slightly edited version of the Karen wedding story. Then they discuss The Tempest. Unlike Nicola, Miranda has actually read it and would quite like to be Ariel, once Lawrie inevitably gets her way and is recast as Caliban. Jan Scott is down for Prospero, which Miranda approves of, because she thinks Jan will do it properly, as “white magic starting to go black … but then he decides he can’t go through with it.” It turns out Miranda has had a crush on Jan since she was a Junior and saw Jan performing an outlaw ballad:

…partly teasing, but more in admiration, Nicola said, “You have been faithful, haven’t you?”

“My middle name,” said Miranda; and added, “As a matter of fact, that’s almost true.”

“Why, what is it?”

“Ruth. The whither thou goest I will go girl. Oh dear,” said Miranda sadly, “after this term, when Jan’s left, will be so drear. Absolutely no one to be interested in at all.”

I think they’re fourteen now, is that right? It’s interesting how accepting Nicola is of Miranda’s feelings for Jan, which are certainly romantic, even if they’re not sexual. The other thing I observed is how often Nicola comments on other girls’ appearances – not just Esther’s beauty, but a detailed list of Monica’s facial features (“The odd thing was, looked at all together, they made an attractive whole”), Tim’s “odd angular face, which remained, disconcertingly, neither absolutely plain nor absolutely pretty” and Miranda (“half-curling dark hair, dark blue eyes, and fierce little hawk face”). It’s exactly the age when girls, even tomboyish, sensible girls like Nicola, start thinking of their appearance in relation to their peers, because it’s finally starting to matter, in terms of popularity and boys.

Antonia Forest also seems to assume that her young readers will be familiar with The Tempest and the story of Ruth, which may be an accurate assumption for that time.

Speaking of The Tempest, has anyone seen the film version with Helen Mirren as a female Prospero? Is it any good?

Next, Chapter Four: Assorted Disappointments

December 26, 2020

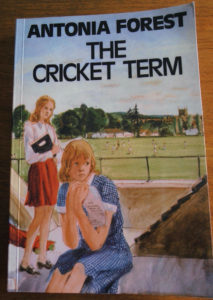

‘The Cricket Term’ by Antonia Forest

I am very happy to be back at Kingscote with Nicola and her friends and enemies for Book Eight of the Marlows series, although it’s been three years since I read End of Term and some of the details of that have faded from my memory. Unfortunately, Girls Gone By decided not to publish Book Seven, The Ready Made Family, but hopefully I won’t need to know about family events from the previous book to understand what’s going on in The Cricket Term.

The cover of this book is not quite as bad as The Thuggery Affair, but it’s not great:

Presumably that’s Nicola in her old blue uniform, looking sad as she clutches something. A failed exam paper or a distressing letter? A student wearing the new red uniform hovers in the background appearing concerned. Is that Miranda? Esther? A prefect? It can’t be Lawrie, who has never in her life been worried about anyone else’s feelings. The back cover features a teacher in a billowing gown, looking like a benevolent vampire as she gazes upon the two girls:

I have so many questions. Why are they all on the roof instead of watching the cricket match? Who is Head Girl this year? Will Evil Lois conspire to throw Nicola off whatever team sport is being played this term (cricket, presumably)? Will there be a school play, with more drama surrounding the casting than on the stage? Is Miranda still in love with Janice? Has Esther finally been reunited with Daks? Is Marie still a pathetic drip? Let’s find out.

Chapter One: Home—

At Trennels, Nicola, Lawrie and Ann pack their bags to return to school — that is, Nicola packs her own suitcase and Ann packs for Lawrie, even though their mother orders Ann to stop acting as everyone else’s unpaid servant. In yet another horrifying revelation about Kingscote’s rules, girls are only allowed to take ONE BOOK to school each term! And it has to be an approved book, which The Mask of Apollo isn’t for Nicola, because it’s only suitable for those in Upper Fifth and above! I haven’t read The Mask of Apollo, but I can’t imagine what’s so scandalous about it — unless the teachers are worried that girls will then start reading Mary Renault’s non-historical books, like The Charioteer and The Friendly Young Ladies, and develop worrying ideas about same-sex relationships. Nicola’s other chosen book is Ramage, some Hornblower-ish novel. Ann, the prig, refuses to smuggle Apollo into school for Nicola, and Lawrie is being a brat and refuses to do Nicola a favour unless Nicola swaps her share of The Idiot Boy, Patrick’s “outgrown pony”. Why would Nicola have a share of The Idiot Boy? Has something happened to Buster? Ginty, by the way, is off snogging Patrick at his house. Maybe not snogging, perhaps just discussing hunting or falconry or Catholic martyrdom.

Oh, good grief, now Karen, the family’s brilliant scholar, has dropped out of Oxford to marry some ancient don who has three children! This is only a year since she left school, so she can’t be more than nineteen years old. What is wrong with this family? Isn’t it bad enough that poor Rowan had to leave school to act as unpaid labourer on a farm she’ll never inherit? Now Karen’s an unpaid housekeeper and nanny for a man probably old enough to be her father (please don’t tell me he was her teacher). I don’t know why they can’t live at Oxford, but they all moved to Trennels, then when that got too much for everyone, Karen moved her new family into the farm manager’s house, kicking out poor Mrs Tranter while Mr Tranter is in hospital. This works out for Karen, because she can send the children to the village school and then Colebridge Grammar and she gets her laundry done by her mother’s servants. Nicola belatedly realises how crafty and self-centred Karen is (“Honestly, you’re like Lawrie!”) and Karen smugly admits this.

Karen’s new stepchildren are Charles/Chas, Rose and Phoebe/Fob, of indeterminate school age. The elder two seem to like Nicola, possibly because she saved Rose’s life? Or at least, found Rose after the child ran away to Oxford a few weeks before? I don’t know whether their mother is dead or divorced. Meanwhile, they’re all eating bread-and-dripping and drinking orange-and-cream, which sounds revolting, while Karen toils away creating some elaborate pudding. She can’t possibly let her family eat “T.V things in packets” because that’s “so unenterprising”. This book is written, and presumably set, in 1974, but apparently none of the Marlow girls have gotten around to reading The Female Eunuch yet.

Chapter Two: Interval

Karen’s husband, Edwin Dodd, has copied some bits out of a sixteenth century Trennels farm log for Nicola (adding a glossary and notes in Latin because Edwin’s a pompous old show-off). The journal is about young Nicholas Marlow, who runs away from school after being beaten for saying something either blasphemous or treasonous, then is presumed dead for years, then turns up at his elder brother’s house and reveals he was at sea with Walter Raleigh. Nicola is, of course, very excited by this. Young Nicholas has also watched “AM” (a Marlow or a Merrick ancestor?) “suffer for the Faith” and die at Tyburn. Then he goes off to be a “player”.

Briefly, Nicola wished she were still friends enough with Patrick Merrick to go charging over, saying ‘Look at this!’

Poor Nicola, thrown over for Ginty. But you deserve better than Patrick, Nicola.

On the way home, Nicola meets Rowan and they discuss a money-making scheme to breed horses and have pony-riding at Trennels. Rowan also gives Nicola some advice about Evil Lois — “Just watch she doesn’t queer your pitch this term too” — and Nicola rightly points out there’s not much she can do about it if Lois does start plotting. Nicola is hoping they’ll win the inter-form cricket match and Rowan advises her not to focus too much on dramatic batting and double centuries, but to concentrate on fielding, bowling and batting singles. Rowan and Nicola both agree that given a choice of being awarded the DSO or scoring fifty against the dastardly Australians, they’d choose fifty against the Australians every time.

I think cricket is the second most boring game in the universe, after golf, so I hope there’s not too much of it in this book. But it sounds as though there will be.

Also, Nicola notes that the older Marlow sisters are unimpressed with Karen:

What with Kay’s silence over Edwin until she’d all but married him, and her crafty effort over the farmhouse, relations between her elder sisters seemed practically non-existent these days.

Did Karen suddenly drop out of Oxford and get married because she was pregnant?

The girls have a gloomy Last Dinner at Trennels before their mother drives them and Daks to the train station, with Nicola proudly wearing a battered old school hat handed down by three of her older sisters, to her mother’s horror.

Next, Chapter Three: -And Away

You may also be interested in reading:

‘Autumn Term’ by Antonia Forest

‘The Marlows and the Traitor’ by Antonia Forest

‘Falconer’s Lure’ by Antonia Forest

‘End of Term’ by Antonia Forest

‘Peter’s Room’ by Antonia Forest

‘The Thuggery Affair’ by Antonia Forest

December 22, 2020

My Favourite Books of 2020

I didn’t read many new books this year. This was a year of re-reading old favourites from my bookshelves, partly because I was craving familiar, comforting reads, but mostly because my beloved local library was closed for most of the year. I did acquire Clara, which allowed me to read ebooks, but I’ve decided I prefer paper books, given a choice.

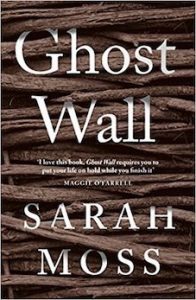

Favourite Novels for Adults

I began the year engrossed in Tana French’s The Wych Elm, an inventive thriller about privilege and identity. I also enjoyed The Secret Place, by the same author, a cleverly constructed murder mystery set in a posh Dublin boarding school, and I liked Anne Tyler’s new novel, Redhead by the Side of the Road, a typically compassionate and thoughtful depiction of a flawed man. However, the most memorable fiction I read this year was Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss, a tense, affecting novella about men using their dubious versions of history to strengthen their hold on power.

I began the year engrossed in Tana French’s The Wych Elm, an inventive thriller about privilege and identity. I also enjoyed The Secret Place, by the same author, a cleverly constructed murder mystery set in a posh Dublin boarding school, and I liked Anne Tyler’s new novel, Redhead by the Side of the Road, a typically compassionate and thoughtful depiction of a flawed man. However, the most memorable fiction I read this year was Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss, a tense, affecting novella about men using their dubious versions of history to strengthen their hold on power.

Favourite Non-Fiction

I liked The Crown: Political Scandal, Personal Struggle and the Years That Defined Elizabeth II, 1956-1977 by Robert Lacey, about the actual history behind the TV series, even though I gave up on watching The Crown after the first series. I didn’t seem to read many non-fiction books this year, which is unusual for me. I think it was due to the lack of access to my library, but also because I was reading so much depressing pandemic-related non-fiction online.

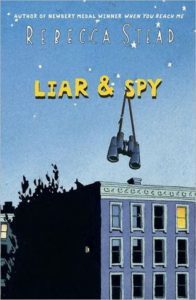

Favourite Books for Children and Teenagers

I enjoyed Kate Constable’s new middle-grade novel, The January Stars, as well as an older novel of hers, Winter of Grace, about a contemplative teenage girl who explores spirituality and religion in a way that isn’t often seen in Australian Young Adult literature. I also liked Rebecca Stead’s Liar and Spy, about a middle-grade boy who bravely faces up to unpleasant reality and devises a clever plan to defeat some school bullies. As always, I enjoyed her depiction of children’s lives in Brooklyn – I have no idea how accurate it is, but she makes New York seem so appealing. I was also entertained (and often confused) by Archer’s Goon by Diana Wynne Jones, which is full of plot twists and surprises. I’m not sure it is truly a children’s book and it lacks the warmth of Howl’s Moving Castle, but it was very clever and intriguing.

I enjoyed Kate Constable’s new middle-grade novel, The January Stars, as well as an older novel of hers, Winter of Grace, about a contemplative teenage girl who explores spirituality and religion in a way that isn’t often seen in Australian Young Adult literature. I also liked Rebecca Stead’s Liar and Spy, about a middle-grade boy who bravely faces up to unpleasant reality and devises a clever plan to defeat some school bullies. As always, I enjoyed her depiction of children’s lives in Brooklyn – I have no idea how accurate it is, but she makes New York seem so appealing. I was also entertained (and often confused) by Archer’s Goon by Diana Wynne Jones, which is full of plot twists and surprises. I’m not sure it is truly a children’s book and it lacks the warmth of Howl’s Moving Castle, but it was very clever and intriguing.  However, my favourite children’s read was, unexpectedly, a novel told partly in verse about a girl living in a Bronze Age Mediterranean culture ruled by superstition. Dragonfly Song by Wendy Orr was an engrossing story about a lifestyle completely unfamiliar to me, told in simple but descriptive language. It has deservedly won a number of literary awards and there’s a good interview with the author about the book here.

However, my favourite children’s read was, unexpectedly, a novel told partly in verse about a girl living in a Bronze Age Mediterranean culture ruled by superstition. Dragonfly Song by Wendy Orr was an engrossing story about a lifestyle completely unfamiliar to me, told in simple but descriptive language. It has deservedly won a number of literary awards and there’s a good interview with the author about the book here.

Favourite Read That Was Not A Book

When life felt really dismal this year, I escaped to Hedgehog Moss Farm, a small farm in the south of France, owned by a young woman who works as a translator and lives with her Eeyore-ish donkey Pirlouit; her llamas, well-behaved Pampelune and escape-artist Pampérigouste; some photogenic cats and chickens; and a gentle giant guard dog called Pandolf. She describes interactions with her animals and her neighbours in such a droll manner that each blog post is a delight. There are beautiful photos and videos of rural life, interspersed with artwork and literary quotes. Her writing style reminds me a little of Gerald Durrell – if she ever decides to write a book, I would happily buy it.

I don’t know what I’m reading these holidays, but I am planning a chapter-by-chapter discussion of Antonia Forest’s The Cricket Term, with the first post up this week (probably). I hope all you Memoranda readers manage to have a relaxing, enjoyable holiday season, after a year we’d all like to forget, and that 2021 brings better news for the world.

December 13, 2020

My New Author Website

My author website has had a makeover!

It had been a few years since I made any significant changes to my author site, but I’ve now fixed all the broken links, updated the information and reduced some of the clutter. Most importantly, it’s now much nicer to view on mobile phones and tablets. (Thanks to HTML5 UP for providing the snazzy free template.)

I hope you find the site useful and easy to access. Let me know if you have any suggestions for further changes.

October 18, 2020

The Mystery of the Dashing Widower: A FitzOsbornes Story

I’d planned to publish this for Love Your Bookshop Day, to say thank you to all the Australian booksellers who have worked so hard to keep us supplied with books during the pandemic. Unfortunately, Love Your Bookshop Day was two weeks ago. I would have known the correct date if I was still on Twitter. But not being on Twitter meant I had lots more spare time to write this. Swings and roundabouts. So, here, belatedly, for booksellers and book readers, is a fluffy FitzOsbornes short story. I’m afraid it won’t make a lot of sense unless you’ve read The FitzOsbornes at War.

The Mystery of the Dashing Widower

One of the most enjoyable aspects of Miss Lancaster’s job at the bookshop — apart from the unlimited access to books, of course — was contemplating the hidden lives of the customers. Such mysteries! There was The Major, a gruff elderly gentleman who always had a Mills and Boon romance concealed in the stack of military history books he brought up to the counter each month. (“For the wife,” he’d muttered, when he saw Miss Lancaster’s glance snag upon Desire is Blind. She wasn’t sure if it would be more endearing if this turned out to be the truth or a lie.) There was the tall, thin lady who was slowly making her way through a badly-foxed copy of The Interpretation of Dreams in the dimmest corner of the shop, marking her place each week with a red cotton thread. There was The Brunette in Blue, who always contrived to be in the shop at the exact same time as The Shy Accountant, although Miss Lancaster had never managed to catch them exchanging a single word, let alone touching.

However, her favourite mystery by far was the Dashing Widower, whom she’d first encountered two years ago when he’d rushed in and begged for book recommendations.

“It’s for my sister,” he’d said. “She’s very clever and has read absolutely everything but we must keep her in bed, doctor’s advice, you see, first baby and all, and magazines and newspapers simply aren’t working anymore.”

“Ah,” said Miss Lancaster, brightening. It had been a very dull afternoon and the young gentleman had blond curls and sparkling blue eyes and a charming smile. “Well, what interests her?”

“The human condition,” he said solemnly, then laughed. “Let’s see. She likes Austen and Trollope and the Brontës and there’s a novel she’s just finished, I wrote down its author — Davey, I have to put you down for a moment while I find that note.” He’d been carrying a dark-haired child, perhaps two years old, who grumbled quietly as he was lowered to the floor. “Look, old chap, a book about yachts, you’ll adore that. Here we are — Rumer Godden. Can that be right? Is that really someone’s name?”

Up close, the gentleman was older than she’d first thought, with scarred flesh running down the side of his face and neck. He limped, and later she realised he had a wooden leg. The war, she supposed. What a tragedy, and then to have lost his wife, too — because surely he was a widower. Why else would a man spend so much time looking after his small children? Because soon after that, he began to visit the shop every couple of weeks or so, sometimes with a baby in a fancy silver perambulator, more often with his son on their way back from sailing toy boats in Hyde Park. He mostly bought books for the children, Ladybirds and Dr Seuss and a beautiful leather-bound collection of fairy tales. Sometimes he accepted further recommendations for his sister (“The Grand Sophy! Oh, yes, that’s perfect.”), but he always claimed he didn’t read himself.

“You do, Daddy,” corrected Davey. “You read about aeroplanes.”

“Yes, maintenance manuals,” said his father, and Miss Lancaster filed that away. Ex-RAF? Former fighter pilot? Current pilot? Except he didn’t ever seem to go to work.

“We had a box of Biggles come in this morning,” she offered. “Excellent condition.” She picked up Biggles Sees It Through and handed it over. A curious expression came over his face and he went very still.

“What’s that?” said Davey, peering closer.

His father shook his head and smiled down at the boy.

“Sorry, lost in thought. Your aunt loved these books. Oh, look, Davey, The Adventures of Wonk: Going To Sea! Shall we get that one?”

Miss Lancaster stayed well away from aeroplanes — indeed, anything military — after that. Her standard recommendation for men who claimed not to read was a collection of humorous short stories, but she didn’t dare suggest P. G. Wodehouse, not after all the fuss about his broadcasts during the war. Nazi propaganda, they’d called it. Sometimes it felt like the war would never be over…

Months later, Miss Lancaster spied the Dashing Widower by The Serpentine with a pretty blonde who looked so much like him that she could only have been his sister. Davey was hurling bread at the ducks, his sister had by then grown big enough to stand on her own legs and the lady was fussing over a smaller baby in the now-familiar perambulator. Her baby? Presumably. She did not, Miss Lancaster had to admit, look like a Biggles fan, but appearances could be deceiving.

However interesting this sighting was, it was nothing compared to the momentous afternoon the following year. Miss Lancaster had been walking through Belgravia. This was not, strictly speaking, on her way home, but sometimes she couldn’t resist the lure of those grand old mansions, so imposing, so intriguing. Since the war, some of them had been turned into embassies — mostly for tiny countries no one had ever heard of, but still, imagine all the fascinating people inside, the diplomats and press officers and spies… She turned a corner and there, across the road, was the Dashing Widower with little Davey, talking to one of the most beautiful women Miss Lancaster had ever seen in real life. She looked like a film star, except she was dressed in a sensible navy trouser suit and her only makeup was a slash of scarlet lipstick. The three of them were standing on the steps of the grandest house on the street and the resemblance between Davey and the woman was striking.

Miss Lancaster did some hasty editing of her mental file. Not a widower, then? Perhaps his beautiful wife was one of those modern career women and he’d agreed to take care of the children? Because his injuries were so serious that he knew he could never work again? Although she suspected that no one who lived in a house like that would ever need to worry about working at any sort of ordinary job. Old money, as her boss had said that morning when he’d returned from that deceased-estate auction in the country. Miss Lancaster sidled rapidly across the road to the neighbouring house and arranged herself behind a marble pillar, where she spent some time with her head bent over her handbag, carefully adjusting and re-adjusting the leather strap.

“I must go,” said the lady. “Meeting Daniel for tea at Westminster.”

Could she be a lady MP?

The woman climbed into a rather battered-looking motor car and Davey waved vigorously as she drove off.

“Bye, Aunt Veronica!” he cried.

Ah. Not his mother, then. An aunt, and this one looked even less like a Biggles reader. Miss Lancaster was just wondering whether she could stroll ahead now, perhaps nod hello and get a glimpse of their foyer as they opened their front door, when a far more impressive motor car pulled up and Cary Grant stepped out.

Well, not Cary Grant, because he was in Hollywood, but close enough, double-breasted pin-striped Savile Row suit and all. Davey ran down the stairs and threw himself at the man.

“Oh, you just missed Veronica,” said the Dashing Widower.

“Good,” said Not Cary Grant, hoisting up Davey. “How’s my boy?” he asked with obvious affection, and now Miss Lancaster could see the family resemblance between those two as well. “Is Julia back yet?”

“Yes,” said the Dashing Widower. “And the meeting went exactly as you predicted. But never fear, she’s plotting her next move.”

“You were away for two days,” said Davey accusingly, holding up two fingers.

“Yes, and I missed you,” said Not Cary Grant.

“Did you miss Mummy?”

“Yes.” He put the child down so that he could pull his suitcase out of the car.

“Did you miss Daddy?”

“Yes.”

“Did you miss Mr Simpkins?”

“Who’s Mr Simpkins?”

“The cat with three legs.”

“The one that chewed up my favourite silk tie? No, I did not miss him. And I wish your uncle would stop foisting all these defective animals on us—”

The three of them disappeared through the glossy red front door, which shut firmly behind them before Miss Lancaster could catch a glimpse of the interior.

Miss Lancaster pursed her lips. This was getting very confusing.

She had progressed no further with solving the mystery of the Devoted Father, as she’d re-named him, on an icy winter’s afternoon a few months later. Anyone who had any choice in the matter would have been tucked up by the fire with tea and crumpets. Davey, however, had birthday money to spend and was taking this book-buying expedition very seriously.

“I could get this one about sailing ships and this quite small book about a fireman or I could get this very, very good book about how to defend a castle from invaders…”

Meanwhile, his little sister was sitting on the rug in the children’s section, her stout legs stretched out in front of her. She was the most angelic-looking child, all golden curls and enormous blue-green eyes, but her rosebud frock had mud smeared down the front. (“Toni fell in a puddle,” Davey had said disapprovingly. “On purpose. And she just laughed.”) Her father was holding up a book for her approval.

Meanwhile, his little sister was sitting on the rug in the children’s section, her stout legs stretched out in front of her. She was the most angelic-looking child, all golden curls and enormous blue-green eyes, but her rosebud frock had mud smeared down the front. (“Toni fell in a puddle,” Davey had said disapprovingly. “On purpose. And she just laughed.”) Her father was holding up a book for her approval.

“I want bunny,” she said.

“We say please when we want something. And we do not need any more bunny books,” said her father. “Now, who’s this? Look, he’s grey and has floppy ears!” He handed her The Story of Babar, which she examined dubiously. “You sit here quietly and look at this for a moment. Davey! Have you decided yet?”

The little boy was frowning at two books. “I decided, but I don’t have enough money. This one costs two shillings and two pence and this very, very good one is three shillings and nine pence.”

“So how much are they, when you add them up?”

“Five shillings and eleven pence. But I only have five shillings and eight pence.” He held out a palmful of coins.

“So how much more money do you need?”

“I’m only four, Daddy,” said Davey. “I can do adding up, but I can’t do adding down.”

“It’s called subtracting and yes, you can. You were doing it this morning. Here, I’m going to lend you thruppence and you can pay me back from your jam jar when we get home. How much do you have now?”

“Five shillings and eleven pence!”

“So if you subtract three pence from five shillings and eleven pence, you get—?”

“Daddy, Toni is climbing the wall.”

Miss Lancaster, distracted by the arithmetic lesson, had also failed to notice the little girl, who had tucked her dress into her bloomers and scaled the bookshelf in the Natural History section as far up as Alpine Flora and Fauna.

“Good Lord, I leave you alone for thirty seconds!” said her father, who’d dashed over to rescue her. “No climbing, Toni! That’s very naughty. You could hurt yourself. And look, now you’ve torn your new dress—”

“Excuse me, I would like to pay for these books, please,” said a firm voice somewhere below the counter.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” said Miss Lancaster, leaning over to take the books and handful of coins from Davey. “Thank you, that’s the exact amount. Shall I wrap them for you?”

“No, thank you. I will put them in my bag.” Davey was carefully stowing them away in his satchel when his father came up, carrying the little girl.

“Give the book to the lady, please,” said the Devoted Father, rather wearily.

“No!” Toni clutched the book and shook her head. Then she suddenly changed her mind and thrust The Bunney-Fluffs’ Moving Day at Miss Lancaster, with a dazzling smile that showed off two new pearly teeth.

“Ah, a bunny book. How nice,” said Miss Lancaster blandly. “That will be 2/6, please. Shall I wrap it for you?”

“Put this in your bag, please, Davey,” said the Devoted Father. “Right! Have we got everything? Toni, where are your mittens? Let’s go or we’ll be late for tea. Remember, we’re going to see Elizabeth this afternoon.”

“Princess Elizabeth?” said Davey, and Miss Lancaster’s eyes widened.

“So we’ll be on our best behaviour, won’t we, Toni?”

“Bunny book,” said Toni.

“Yes, you can share your bunny book with her. I’m sure she’ll love that. Good afternoon,” he said, nodding to Miss Lancaster. “Terribly sorry about the mountaineering. Won’t happen again.” He herded the children out and the bell clanged behind them.

Miss Lancaster propped her elbow on the counter and her chin on her hand. She was considering getting some cushions for the children’s section and perhaps a Winnie-the-Pooh to sit on the windowsill. Her boss said they should not encourage children in the shop because they were noisy and smelly and had sticky fingers, but Miss Lancaster had pointed out that this also applied to a significant number of their grown-up customers. She very much enjoyed observing the various children who visited the bookshop and remained hopeful that one day, little Davey would let slip enough information to enable her to solve the mystery of the Devoted Father. In the meantime, she was going to put the kettle on. She was planning to have a nice cup of tea and an arrowroot biscuit. And then she had a box of Margery Allingham detective stories to sort through. Miss Lancaster really did adore her job.

© Michelle Cooper 2020

September 25, 2020

Memoranda Turns Ten

Ten years ago today, I started this blog with a post about how I learned to hate poetry. Three hundred and twenty-one posts and about two hundred thousand words later, here I am, still blogging, although far less frequently than at the start.

Here’s a selection of Memoranda posts from the past decade.

First, ten discussions about children’s books, in no particular order:

Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome

Friday’s Tunnel by John Verney

Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones

The Years of Grace and Growing Up Gracefully by Noel Streatfeild

Peter’s Room by Antonia Forest

Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner

And ten discussions about favourite novels and novelists:

The Cazalet Chronicles by Elizabeth Jane Howard

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons

The Mapp and Lucia Novels by E. F. Benson

The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

What I’ve Been Reading: Muriel Spark

Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead by Paula Byrne

Careful, He Might Hear You by Sumner Locke Elliott

Dear Dodie: The Life of Dodie Smith by Valerie Grove

Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford and Meet the Mitfords

Here are ten posts about writing:

How To Write a Novel, about writing advice

Same Book, But Different, on editing books for different countries

Book Banned, Author Bemused – my book got banned in the US!

Five Ways in Which Writing a Novel is Like Making a Quilt

The Creative Vision Versus the Marketing Department

Goatbusters, or How The Writerly Mind Works

The ‘Aha!’ Moment and Three Things That Didn’t Happen In The Montmaray Journals

Mrs Hawkins Provides Some Advice For Writers

And ten rants about book-related topics:

Just a Girls’ Book, followed by Just A Girls’ Book, Redux and Girls and Boys and Books, Yet Again

Looking for a Good, Clean Book

I Hate Your Characters, So Your Book Stinks

A Public Service Announcement: Smoking Is Bad For You

Here’s to another ten years of Memoranda. Hopefully I’ll be blogging a bit more from now on, because I’ve just deleted my Twitter account.

August 2, 2020

In Which I Finally Purchase An eReader

I am not what is termed an ‘early adopter’ of new technology. I don’t own a smart phone or an iPad or a digital radio, I don’t subscribe to any streaming services, and my entire music collection consists of cassettes and CDs (played on my trusty 1990s Panasonic boombox). In fact, some people who know me have gone so far as to mention the word ‘Luddite’, but this is inaccurate. I’m not a technophobe. I studied maths, physics and computer studies at high school, I have a science degree, and at Day Job, I’m the go-to person for solving tech problems, whether it’s modifying our database software or unjamming the photocopier.

Outside work, though, I only use new technology if it’s both affordable and essential. That’s why I’ve avoided ebooks for the last decade. I already had a cheap, efficient way to read books, so why would I pay a lot of money to buy some electronic reading device? Anyway, I spend all day looking at screens for work. I didn’t want to spend my leisure time staring at yet another screen.

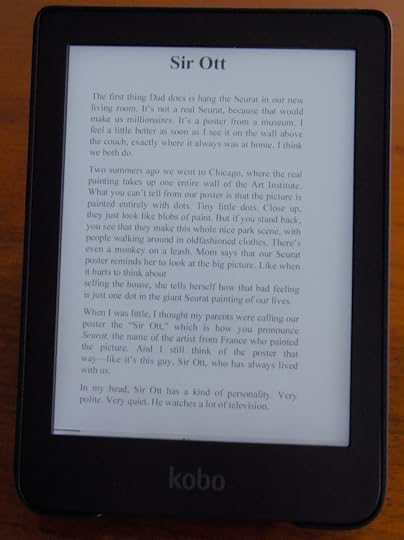

However, with my library now closed for physical book borrowing for the foreseeable future and with limited access to bookshops, I finally decided to invest in an eReader. There are really only two options for Australians — a Kindle or a Kobo. I don’t much like Amazon and I wanted a device compatible with library ebooks, so that left me with a choice of three different models of Kobo eReaders. I chose Clara, the smallest (and cheapest). Clara has a six inch screen, fits comfortably in my little hand, weighs less than a paperback, but can store up to 6000 ebooks.

There are various options for screen brightness and colour, font type, font size and moving between pages and chapters, some of which work better than others for me. I like being able to increase the size of the print, although as the screen is fairly small, I need to swipe up and down to read a single page. I could have avoided this problem if I’d bought one of the bigger models, but they’d probably have been more awkward to hold. (In different times, I’d have visited a shop and tried out the various models before I bought anything. But if I could go to shops, I’d also be able to go to the library, so I wouldn’t need an eReader.) It takes about two hours to charge Clara fully and this apparently lasts several weeks, as long as you turn the power off whenever you finish reading. I discovered that if you use the Sleep Mode, it eats up energy very quickly. However, if you’ve turned off the power, you need to re-set the viewing options when you open up your book again, which is annoying.

Clara also provides ways to bookmark pages, highlight sections and check word definitions using the built-in multilingual dictionaries, but I haven’t tried out these features yet. I did find it a bit awkward to swipe back to previous pages to re-read an earlier section — that’s definitely easier to do in a paper book.

Clara displays nice, sharp images, including book covers, in shades of grey. Apparently you can read graphic novels and picture books with Clara, but I can’t imagine it would be a very enjoyable experience, compared to paper editions.

I bought a separate black leather cover with a magnetic clasp, which not only keeps Clara safe and clean, but can be flipped to make a convenient hands-free stand. This is a vast improvement on my usual propping-a-paperback-against-another-book-and-using-one-hand-to-stop-it-from-snapping-closed, which is how I tend to read books while eating lunch.

Clara also asked me about my favourite books and provided some amusingly unhelpful recommendations for future reading. Here’s what she thinks I should read next: all of Anne Tyler’s recent novels (which I’ve already read); The Complete Works of Plato (no thanks); The Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels (ha ha! actually, I have read that, a long time ago); Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes (what?); and Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. I fear Clara has the wrong impression of me. I hate to disappoint her, but my next read is actually a library copy of Courtney Milan’s Proof by Seduction, a Regency romance whose cover features a lady in distinctly unRegency underwear swooning across a bed. I have downloaded a free copy of Machiavelli’s The Prince, though.

I was interested to see whether I’d read and comprehend ebooks differently to paper books. I think I might read ebooks quicker, with more scanning and less contemplation. But the two ebooks I’ve finished so far have been YA and middle-grade novels, so maybe I’d read them quickly anyway?

In conclusion, Clara and I are getting on very well, thus far. Please do let me know if you have any helpful e-reading tips.

June 21, 2020

‘The January Stars’ by Kate Constable

Disclaimer, because this is an Australian book: I’ve never met Kate Constable but we internet-know each other and she is a regular commenter on this blog. However, I wouldn’t write nice things about her books unless I really, truly enjoyed them. If I don’t like something written by an Australian writer I know, I just don’t write about it. I rarely spend time blogging about books I don’t like (unless the books are amusingly bad and the author is either dead or so famous that my opinion is irrelevant to their well-being).

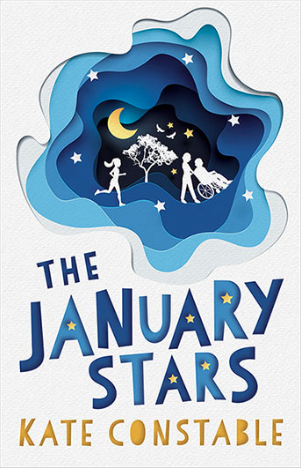

The January Stars by Kate Constable is a warm-hearted, thoughtful novel about family, in which twelve-year-old Clancy and her older sister Tash accidentally kidnap their grandpa from his awful nursing home and set off on an adventure to find him a better life. In the fine tradition of children’s literature, the grown-ups are mostly dead, absent or useless, so the girls need to be resourceful and clever. Clancy is an endearing and relatable protagonist — initially shy and anxious, reluctant to take risks or challenge the rules, but ultimately able to draw on hidden reserves of resilience and courage. It’s lovely to watch how her relationship with her confident older sister evolves. I also liked Pa, who has had a stroke, is partly paralysed and has aphasia, but is always depicted as a strong-minded person with a sense of humour and varied interests. He’s also shown as able to communicate effectively with his granddaughters, despite the challenges posed by his speech and language difficulties. (I did wonder why he didn’t have a communication board attached to his wheelchair or some sort of electronic communication aid, but perhaps it got lost in the tumult of the kidnapping.)

Something I really loved about this book were the vivid descriptions of the settings, from inner-city Melbourne apartment blocks to leafy outer suburbs to a rural ashram and a seaside town. I dislike it when children’s books have either generic settings (for example, Odo Hirsch’s novels, set in vaguely European cities) or else vast swathes of descriptive prose that read like creative writing exercises, but The January Stars gets it exactly right, for my tastes.

Kate Constable’s books often involve fantasy and in this one, Clancy begins to believe her dead grandmother is assisting their quest. There is also a short section involving a time-slip or possibly a parallel, pocket universe, which the girls decide not to think about too much because “if you can explain magic, it’s not magic anymore”. I mean, personally, I would not have been able to resist researching the magic bookshop and its owner, but some readers (and authors) prefer mysterious events to remain enigmatic.

Also, I don’t often pay attention to book covers, but I need to mention this one because it’s so eye-catching. It looks like a paper sculpture, but I believe it was done digitally by Debra Bilson. It’s a very appropriate image for a beautiful, layered story.

If you like the sound of The January Stars, you may want to try Cicada Summer, for slightly younger readers. Poor Eloise, mute with grief over her dead mother, is dragged off to live in a drought-affected country town with her odd grandmother. Fortunately, there is an intriguing old family mansion to explore, as well as a mysterious but friendly girl who might possibly have slipped through time … This is a charming, poignant story with a genuinely surprising and clever twist.

If you like the sound of The January Stars, you may want to try Cicada Summer, for slightly younger readers. Poor Eloise, mute with grief over her dead mother, is dragged off to live in a drought-affected country town with her odd grandmother. Fortunately, there is an intriguing old family mansion to explore, as well as a mysterious but friendly girl who might possibly have slipped through time … This is a charming, poignant story with a genuinely surprising and clever twist.

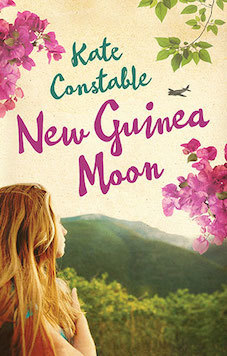

I also really enjoyed New Guinea Moon, set in the 1970s, in which Australian teenager Julie visits her father, a commercial pilot working in Papua New Guinea. It reminded me a little of those Rumer Godden books in which a young white woman arrives in India, falls in love with it, gets into conflict with the old India hands over their racist views, blunders about for a while naively causing damage, then departs, sadder but wiser. Papua New Guinea is Australia’s closest neighbour, but is rarely part of our literary world, especially in children’s fiction, so this novel was fascinating to read. In common with many Australians, I have a family connection to PNG — my father worked there in the 1960s — and I also grew up in Fiji in the 1970s, in and beside an expat community that sounds very similar to the one Julie finds herself in. The descriptions of that community — the insularity, snobbishness and racism — felt very true to life, in my opinion. I also wallowed in all the lush, evocative descriptions of tropical life in this book — the sudden downpours, the geckos falling off the ceiling, the bright bougainvillea against whitewashed cement walls, the tang of salty plums. I did marvel at Julie’s mother sending her all the way to another country to stay with a near stranger for a summer (particularly given what subsequently happens in this story!), but hey, it was the 1970s — they did things differently back then.

I also really enjoyed New Guinea Moon, set in the 1970s, in which Australian teenager Julie visits her father, a commercial pilot working in Papua New Guinea. It reminded me a little of those Rumer Godden books in which a young white woman arrives in India, falls in love with it, gets into conflict with the old India hands over their racist views, blunders about for a while naively causing damage, then departs, sadder but wiser. Papua New Guinea is Australia’s closest neighbour, but is rarely part of our literary world, especially in children’s fiction, so this novel was fascinating to read. In common with many Australians, I have a family connection to PNG — my father worked there in the 1960s — and I also grew up in Fiji in the 1970s, in and beside an expat community that sounds very similar to the one Julie finds herself in. The descriptions of that community — the insularity, snobbishness and racism — felt very true to life, in my opinion. I also wallowed in all the lush, evocative descriptions of tropical life in this book — the sudden downpours, the geckos falling off the ceiling, the bright bougainvillea against whitewashed cement walls, the tang of salty plums. I did marvel at Julie’s mother sending her all the way to another country to stay with a near stranger for a summer (particularly given what subsequently happens in this story!), but hey, it was the 1970s — they did things differently back then.

You can find more about Kate Constable’s books here.