Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 3

February 20, 2024

What I’ve Been Reading

The Deadly Daylight by Ash Harrier was an enjoyable middle grade mystery, the first in a series featuring Alice England. Alice is an unusual twelve-year-old who works in her father’s funeral parlour and is able to detect messages from the dead. She is mystified by social conventions and polite lies, she notices details that others miss, and she speaks like an elderly librarian, so predictably, she finds it difficult to make friends with other children. However, she is drawn to an equally unusual girl at school, Violet, who is dangerously allergic to sunlight, and together they solve the mystery of Violet’s uncle’s strange death. It takes a little too long for anything exciting to happen, but there are lots of interesting twists in the final section and I liked watching Alice and Violet learn to compromise and become better at friendship. There is also a diverse cast of characters with disabilities – Alice has a congenital leg disability that makes it difficult for her to walk; Violet and her family have solar urticaria. The author and her neurodiverse daughter have written a thought-provoking article in a recent edition of Magpies discussing how characters with disabilities are portrayed in children’s literature and whether “non-marginalised allies” can successfully write about disabled and neurodivergent characters. The Deadly Daylight will appeal to confident middle grade readers who like mysteries with a hint of the supernatural – and if they enjoy it, there are two more novels about Alice’s adventures.

The Deadly Daylight by Ash Harrier was an enjoyable middle grade mystery, the first in a series featuring Alice England. Alice is an unusual twelve-year-old who works in her father’s funeral parlour and is able to detect messages from the dead. She is mystified by social conventions and polite lies, she notices details that others miss, and she speaks like an elderly librarian, so predictably, she finds it difficult to make friends with other children. However, she is drawn to an equally unusual girl at school, Violet, who is dangerously allergic to sunlight, and together they solve the mystery of Violet’s uncle’s strange death. It takes a little too long for anything exciting to happen, but there are lots of interesting twists in the final section and I liked watching Alice and Violet learn to compromise and become better at friendship. There is also a diverse cast of characters with disabilities – Alice has a congenital leg disability that makes it difficult for her to walk; Violet and her family have solar urticaria. The author and her neurodiverse daughter have written a thought-provoking article in a recent edition of Magpies discussing how characters with disabilities are portrayed in children’s literature and whether “non-marginalised allies” can successfully write about disabled and neurodivergent characters. The Deadly Daylight will appeal to confident middle grade readers who like mysteries with a hint of the supernatural – and if they enjoy it, there are two more novels about Alice’s adventures.

I also enjoyed London: A Guide for Curious Wanderers, written by history blogger and London guide Jack Chesher, with beautiful illustrations by Katharine Fraser. It’s full of quirky, fascinating facts about London’s history, from Roman to modern times. There are sections on London’s secret tunnels, hidden rivers, lost islands, odd statues, street furniture, post boxes and more. It’s not comprehensive, but it’s a really intriguing read, complete with maps for your own self-guided tours if you’re lucky enough to be visiting London.

I also enjoyed London: A Guide for Curious Wanderers, written by history blogger and London guide Jack Chesher, with beautiful illustrations by Katharine Fraser. It’s full of quirky, fascinating facts about London’s history, from Roman to modern times. There are sections on London’s secret tunnels, hidden rivers, lost islands, odd statues, street furniture, post boxes and more. It’s not comprehensive, but it’s a really intriguing read, complete with maps for your own self-guided tours if you’re lucky enough to be visiting London.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton was an odd, but engrossing, novel set in New Zealand, in which a collective of anarchist guerrilla gardeners find themselves in an uneasy alliance with an American tech billionaire. It’s described as a ‘literary thriller’ but the Booker-Prize winning author has also stated she aimed to emulate Jane Austen’s prose style, so unsurprisingly, it doesn’t really work as a thriller. There’s a lot of telling rather than showing, the dialogue (which includes an eight-page monologue by one particularly annoying character about the evils of capitalism) is often unrealistic, the villain is cartoonish, there’s often too much detailed description when the pace needs to be faster, and the conclusion is abrupt with no real resolution. On the other hand, many of the characters are well-drawn, recognisable and amusing; the New Zealand setting is beautifully described; and there are a lot of interesting discussions about the environment, technology and the compromises that environmentalists and leftist politicians need to make in modern society in order to progress their goals. I also liked all the guerrilla gardening tips.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton was an odd, but engrossing, novel set in New Zealand, in which a collective of anarchist guerrilla gardeners find themselves in an uneasy alliance with an American tech billionaire. It’s described as a ‘literary thriller’ but the Booker-Prize winning author has also stated she aimed to emulate Jane Austen’s prose style, so unsurprisingly, it doesn’t really work as a thriller. There’s a lot of telling rather than showing, the dialogue (which includes an eight-page monologue by one particularly annoying character about the evils of capitalism) is often unrealistic, the villain is cartoonish, there’s often too much detailed description when the pace needs to be faster, and the conclusion is abrupt with no real resolution. On the other hand, many of the characters are well-drawn, recognisable and amusing; the New Zealand setting is beautifully described; and there are a lot of interesting discussions about the environment, technology and the compromises that environmentalists and leftist politicians need to make in modern society in order to progress their goals. I also liked all the guerrilla gardening tips.

I finally got around to reading Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, the “eighth Harry Potter story”, several years after everyone else. This is the published ‘rehearsal script’ of the six-hour play, based on an original story by J.K. Rowling, written by Jack Thorne and directed by John Tiffany. It’s essentially official fan-fiction, set nineteen years after the defeat of Voldemort, in which Albus Potter and his best friend Scorpius Malfoy learn not to mess around with time-travel and Harry yet again proves to be clueless about human relationships. I loved all the plot twists and magical world-building, even though it didn’t make complete sense. (Seriously, Hermione using an easily-solved riddle to hide a Time-Turner that shouldn’t even exist? And let’s not even try to imagine the logistics of that whole Voldemort thing.) But mostly I wondered why the story insisted on shoe-horning in girlfriends for Albus and Scorpius when it was clear that the deep love and trust between the two boys was driving the whole narrative. Is no-one allowed to be gay in this magical world (apart from dead closeted Dumbledore and his dead sociopathic love interest Grindelwald)? Scorpius was definitely my favourite character, and I liked how Draco was, predictably, a far more functional parent than poor abused orphan Harry. I have no idea how the cast and crew manage to translate all the magical action of the script onto the stage, but it must be amazing to watch.

I finally got around to reading Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, the “eighth Harry Potter story”, several years after everyone else. This is the published ‘rehearsal script’ of the six-hour play, based on an original story by J.K. Rowling, written by Jack Thorne and directed by John Tiffany. It’s essentially official fan-fiction, set nineteen years after the defeat of Voldemort, in which Albus Potter and his best friend Scorpius Malfoy learn not to mess around with time-travel and Harry yet again proves to be clueless about human relationships. I loved all the plot twists and magical world-building, even though it didn’t make complete sense. (Seriously, Hermione using an easily-solved riddle to hide a Time-Turner that shouldn’t even exist? And let’s not even try to imagine the logistics of that whole Voldemort thing.) But mostly I wondered why the story insisted on shoe-horning in girlfriends for Albus and Scorpius when it was clear that the deep love and trust between the two boys was driving the whole narrative. Is no-one allowed to be gay in this magical world (apart from dead closeted Dumbledore and his dead sociopathic love interest Grindelwald)? Scorpius was definitely my favourite character, and I liked how Draco was, predictably, a far more functional parent than poor abused orphan Harry. I have no idea how the cast and crew manage to translate all the magical action of the script onto the stage, but it must be amazing to watch.

Also – a reminder that I still have some free one-month subscriptions to Emily Gale’s substack, Voracious, to give away. Leave a comment below if you’re interested.

January 18, 2024

‘The Goodbye Year’ by Emily Gale

What a great start to my 2024 reading! I loved The Goodbye Year by Emily Gale, a Middle Grade novel about twelve-year-old Harper, who has a lot to worry about as she starts her final year of primary school in 2020. Her parents suddenly announce that they’re off to Yemen to work as nurses in a war zone, leaving Harper behind under the care of an eccentric grandmother she barely knows. Her best friends have been made school captains and don’t seem to have time for her any more, some horrible kids are bullying her … and then COVID hits. As if that’s not bad enough, there’s also a mysterious old cadet badge that keeps popping up in the wrong places and a pair of ancient spectacles that fits Harper perfectly, which may just be connected to a ghost hanging out in the school library that only she can see.

What a great start to my 2024 reading! I loved The Goodbye Year by Emily Gale, a Middle Grade novel about twelve-year-old Harper, who has a lot to worry about as she starts her final year of primary school in 2020. Her parents suddenly announce that they’re off to Yemen to work as nurses in a war zone, leaving Harper behind under the care of an eccentric grandmother she barely knows. Her best friends have been made school captains and don’t seem to have time for her any more, some horrible kids are bullying her … and then COVID hits. As if that’s not bad enough, there’s also a mysterious old cadet badge that keeps popping up in the wrong places and a pair of ancient spectacles that fits Harper perfectly, which may just be connected to a ghost hanging out in the school library that only she can see.

There is a LOT going on here and for the first section of the book I wasn’t sure the author could pull everything together, but she manages it well and the conclusion is perfect (and made me cry). There’s so much to like about this book, but I especially loved the way history was presented for young readers, drawing parallels between the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1919 and the COVID pandemic a hundred years later, and emphasising the importance of libraries and historical archives. The characters are also well drawn. Harper is such a sweetheart – she’s anxious and shy, but stoic and brave when she needs to be, considerate of others and a good friend. Her grandmother Lolly is an independent, strong older woman, the child characters, even the bullies, are well-rounded, and there are some adorable dogs and cats. The ghost story is poignant and the associated historical artefacts are woven into the plot with a clever twist that I didn’t see coming but worked very well. I did have one question that didn’t seem to be answered. If you’ve read the book – do we ever find out the cause of the estrangement between Lolly and Liz? I’d thought something would come out when the family tree was revealed, but if it did, I missed it (admittedly, there were a dozen other things going on at the same time.) The Goodbye Year is highly recommended for young readers interested in history and is a worthy winner of the 2023 Young People’s History Prize in the NSW Premier’s History Awards.

Emily Gale has a Substack called Voracious, in which she discusses writing and children’s literature. I recently subscribed to it and have been given some free one-month gift subscriptions to give away. You can read everything at Voracious for free for a month, then either cancel your subscription or choose to continue to subscribe for a fee (currently $5/month or $50/year but I took advantage of a special Christmas 40% off discount). If you’d like a free one-month’s subscription to Voracious, leave a comment below – I’ll give the subscriptions to the first three people who comment asking for a subscription.

December 10, 2023

What I’ve Been Reading: Non-fiction about Mid-20th Century England

London’s Lost Department Stores: A Vanished World of Dazzle and Dreams by Tessa Boase was a short, engrossing history of the grand and not-quite-so-grand department stores of London. In the early 1900s, there were more than a hundred of these stores, offering an extraordinary range of specialised services and products. Galeries Lafayette was renowned for its Parisian fashions and realistic wax mannequins with real human hair arranged in chic tableaux in the windows; Kennards in Croydon had a rooftop zoo and miniature steam railway; Gamages “sold alligators, Scouts’ kits, magic tricks and motor accessories”; Army and Navy Stores had a 1000-page catalogue from which its members could “order anything from dinner gongs, to laxatives, to ear trumpets, trusses and hair restorer.”

This book contains lots of fascinating photos, maps and anecdotes, as well as a discussion of how the stores reflected societal changes – for example, when shop assistants rebelled against being forced to “live in” (that is, pay rent to the shop owners to live in cramped dormitories above the store where they worked) and went on strike for better working conditions. Many of the department stores closed down in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by further decline with the rise of shopping malls, online retail and, of course, the COVID pandemic. I worked as a teenager in the old Grace Bros store on Sydney’s Broadway (now closed down, gutted and turned into a Westfield Shopping Centre), when the cashiers still used a pneumatic tube system to transport cylinders of cash from the service counters to the cashiers department and we would be regularly herded into the decaying ballroom for staff motivational speeches, so this was a fun, nostalgic read for me.

1950s Childhood by Janet Shepherd and John Shepherd also covers a lot for such a short book. There are chapters on post-war family life, changes to the school system following the 1944 Butler Education Act, how child welfare was improved by the introduction of the NHS, and what children ate after rationing ended. I especially enjoyed the photos – children playing in the street with no worries about traffic, entertaining themselves with Meccano and Dinky toy trucks, reading Beano, and gazing enthralled at a black-and-white television screen the size of a shoebox.

School Songs and Gymslips: Grammar Schools in the 1950s and 1960s by Marilyn Yurdan was a “light-hearted investigation” prompted by the author’s memories of her education at Holton Park, a girls’ grammar school in Oxfordshire. It includes a foreword by then Home Secretary Theresa May, who attended the school in the 1970s. This was a gentle, nostalgic look at hideous school uniforms, pointless school rules, eccentric teachers and disgusting school dinners, as well as more enjoyable experiences outside school involving pop records, cinema, dancing and fashion.

Don’t Knock the Corners Off by Caroline Glyn is an even more vivid and interesting look at school life in the 1960s, because it was written by a fifteen-year girl in 1963. No ordinary schoolgirl, it must be said – this was written as she was preparing for her second exhibition of paintings, her first poem had been published at the age of seven, and oh, she was also the great granddaughter of Elinor Glyn. This is a clearly autobiographical novel, about a free-spirited, artistic girl who doesn’t fit into the rigid English school system. Antonia starts off at a tough state primary school where she’s bullied mercilessly; then she applies to a posh girls’ grammar school where she’s forced to do homework and follow nonsensical rules; then she moves to a slightly more relaxed co-ed grammar school where she drifts along fairly happily until the headmaster realises how clever she is and tries to force her to do some work. She spends a term at the Sorbonne, then ends up at an art school where she finally feels she belongs. The voice is authentic and lively, often funny and very clearly the work of a teenager, full of complaints about how dull and stupid the other students are and how awful the teachers are and how much she hates maths.

Caroline Glyn, as would be expected from this novel, led a far from conventional life. She had published five novels by the time she was 21, lived in a tiny houseboat near Cambridge, studied art in Paris, became a nun, moved to Australia and died alone at the age of 32 while scrubbing the convent floor. Her former boyfriend wrote:

“Caroline was far more than merely ‘unusual’, she was unique … She had a terrific sense of humour and sense of fun, and we laughed all the time. Of course she had deep neuroses which defy all analysis, as she well knew … her flame flickered so momentarily before she went away to the Other Regions in which she so steadfastly believed. God was as real to her as the dacquiri in the photo, and she absolutely believed in angels and archangels, and often talked about them. She was only half here, and she left so soon to go back to where she belonged.”

The Mad Boy, Lord Berners, My Grandmother and Me by Sofka Zinovieff was a fascinating family memoir by the granddaughter of Robert Heber-Percy, the Mad Boyfriend of Lord Berners. Lord Berners, who was immortalised in Nancy Mitford’s novels as Lord Merlin, was a composer, writer and painter who threw beautiful parties at Faringdon House, where a flock of dyed pigeons circled over gatherings of famous guests – the Mitfords, Evelyn Waugh, the Lygon family who were portrayed in Brideshead Revisited, Gertrude Stein, H.G Wells, Elsa Schiaparelli, Salvador Dali, the Sitwells, the Betjemans, Diaghilev. Lord Berners and the Mad Boy made an odd couple, as Robert was three decades younger, uneducated, violent, “a hothead who rode naked through the grounds”, but the household situation became even odder when Robert suddenly married his pregnant girlfriend Jennifer Fry and moved her in to Faringdon during the Second World War. Unsurprisingly, the marriage didn’t last and Jennifer and her daughter Victoria moved away, but Victoria’s daughter unexpectedly inherited Faringdon after her grandfather decided she was the only “sensible one” in the family. Although she has now sold the house, she did own it for decades, attempting to restore it after years of neglect and discovering some of the secrets of its famous inhabitants and guests. This book is beautifully written and illustrated, with intriguing anecdotes and photographs, and will appeal to fans of the Mitfords and Brideshead Revisited.

September 11, 2023

What I’ve Been Doing Lately

Not writing, unfortunately, and not much book reading either, hence the lack of blog posts.

What I have been doing is:

– growing big, crunchy, delicious radishes.

Apparently what you need to grow large radishes is lots of sun, lots of water, lots of organic fertiliser, and being ruthless when thinning the seedlings.

– sewing a quilt.

Hand-quilting while listening to podcasts or audiobooks is very relaxing and I have now managed to use up almost all of my fabric and batting stash, so hopefully I will not be tempted to do any more sewing.

– painting my bedroom pink. It looks very cheerful now.

– chatting with producer Lucy Butler about a television series she’s working on.

(I’ve also been doing less fun stuff, such as working at Day Job and having an infected tooth extracted, but you don’t want to know about that.)

Some miscellaneous memoranda:

– From the Smithsonian Magazine: An Icelandic Town Goes All Out to Save Baby Puffins. Did you know baby puffins are called pufflings? Pufflings!

– Here I am, being quoted in a dictionary! (I do not think it is a proper dictionary.)

– Excellent discussion here regarding whether Timmy the dog from the Famous Five was a border collie or not. I especially liked the speculation about why George in the new BBC series is wearing modern clothes while the rest are dressed in 1950s clothes (“Maybe she is from our time and Uncle Quentin invented a Time Machine and she got sent back”) and whether Julian grew up to be Tory MP Julian Fawcett from Ghosts.

– Speaking of Ghosts, the fifth and final series is released in November. I love this show and I’ll be sad to see the end of it. (Obviously I mean BBC Ghosts, not the American one, which looks awful, although hopefully it’s making the original creators lots of money. Fellow Australians, you can watch Series 4 of the proper Ghosts on ABC iView now.)

February 21, 2023

What I Read On My Holidays

Yes, those holidays that ended last month. Better late than never. Here are the books I found the most interesting.

I enjoyed The Guggenheim Mystery by Robin Stevens, an entertaining middle grade novel, featuring Ted, a twelve-year-old British boy who visits his American relatives in New York and finds himself solving an art heist mystery. This is a sequel to The London Eye Mystery by the late Siobhan Dowd, who died the year that book was published but had planned to write a New York sequel. Ted is presumably on the autistic spectrum, although he’s never labelled as such, and some parts of his characterisation seemed a little unlikely. He has amazing powers of memory, logic and pattern recognition which he uses to solve the mystery, but he also somehow copes amazingly well with the noise, confusion and changes to his routine during his holiday, without any meltdowns and with everyone around him being consistently understanding and accommodating. Still, it’s nice to read about the positives of neurodiversity and children with autism spectrum disorders and their siblings, classmates and friends would relate to many of the scenes in this book. The mystery is interesting and cleverly plotted, and I liked the behind-the-scenes look at the Guggenheim Museum.

I enjoyed The Guggenheim Mystery by Robin Stevens, an entertaining middle grade novel, featuring Ted, a twelve-year-old British boy who visits his American relatives in New York and finds himself solving an art heist mystery. This is a sequel to The London Eye Mystery by the late Siobhan Dowd, who died the year that book was published but had planned to write a New York sequel. Ted is presumably on the autistic spectrum, although he’s never labelled as such, and some parts of his characterisation seemed a little unlikely. He has amazing powers of memory, logic and pattern recognition which he uses to solve the mystery, but he also somehow copes amazingly well with the noise, confusion and changes to his routine during his holiday, without any meltdowns and with everyone around him being consistently understanding and accommodating. Still, it’s nice to read about the positives of neurodiversity and children with autism spectrum disorders and their siblings, classmates and friends would relate to many of the scenes in this book. The mystery is interesting and cleverly plotted, and I liked the behind-the-scenes look at the Guggenheim Museum.

I had The Palace Papers by Tina Brown on reserve at the library for months and it became available just as Prince Harry started promoting his memoir, which meant that I had had more than enough of royalty by the time I finished reading this. The Palace Papers is a gossipy, well-researched history of the British royal family over the last twenty-five years. It focuses on the women who schemed and plotted to marry into royalty — Camilla Parker-Bowles, Kate Middleton and Meghan Markle — while also covering some of the many recent royal scandals. These include phone hacking by the press, servants selling lurid stories, Harry’s mental health problems and drug abuse, and Andrew’s financial scandals and friendship with Jeffrey Epstein and civil court settlement with a young trafficked woman. But mostly the book is about how utterly pointless the modern royals are, with their existence depending on positive press coverage. Some of the royals (notably William and Kate) seem to ‘manage’ the press more effectively than others, but no one comes out of this book well. The late Queen tended to ignore dangerous problems (notably, Andrew), Charles is self-pitying and selfish, Camilla has no morals, Andrew is a spoilt brat, Edward and Sophie are money-grubbing. Harry comes across as a vulnerable and damaged man who never grew up, while Meghan is depicted as shallow, rude and deluded. I finished the book wondering why on Earth intelligent young women such as Kate and Meghan would want to join such a dysfunctional family – surely if they’d wanted a wealthy lifestyle, it could have been achieved more easily than by marrying a prince? I have zero interest in reading Prince Harry’s Spare, but unfortunately, Australians are required to continue to have some interest in Britain’s version of the Kardashians, because whoever is on the British throne is also our nation’s Head of State.

I had The Palace Papers by Tina Brown on reserve at the library for months and it became available just as Prince Harry started promoting his memoir, which meant that I had had more than enough of royalty by the time I finished reading this. The Palace Papers is a gossipy, well-researched history of the British royal family over the last twenty-five years. It focuses on the women who schemed and plotted to marry into royalty — Camilla Parker-Bowles, Kate Middleton and Meghan Markle — while also covering some of the many recent royal scandals. These include phone hacking by the press, servants selling lurid stories, Harry’s mental health problems and drug abuse, and Andrew’s financial scandals and friendship with Jeffrey Epstein and civil court settlement with a young trafficked woman. But mostly the book is about how utterly pointless the modern royals are, with their existence depending on positive press coverage. Some of the royals (notably William and Kate) seem to ‘manage’ the press more effectively than others, but no one comes out of this book well. The late Queen tended to ignore dangerous problems (notably, Andrew), Charles is self-pitying and selfish, Camilla has no morals, Andrew is a spoilt brat, Edward and Sophie are money-grubbing. Harry comes across as a vulnerable and damaged man who never grew up, while Meghan is depicted as shallow, rude and deluded. I finished the book wondering why on Earth intelligent young women such as Kate and Meghan would want to join such a dysfunctional family – surely if they’d wanted a wealthy lifestyle, it could have been achieved more easily than by marrying a prince? I have zero interest in reading Prince Harry’s Spare, but unfortunately, Australians are required to continue to have some interest in Britain’s version of the Kardashians, because whoever is on the British throne is also our nation’s Head of State.

I then read a lovely book about trees. The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben is an engaging, chatty account of how trees protect themselves and their young, adapt to challenging circumstances, fight for resources with other species, and share information, food and water with each other via a network of roots and fungi (the ‘wood wide web’). Trees can live for hundreds and even thousands of years and the author describes some amazing trees – for example, a single quaking aspen in Utah that covers 100 acres, with forty thousand trunks growing from the same roots, and a beech stump that was cut down five hundred years ago but has been kept alive all that time by neighbouring beeches feeding it sugar. The author is a German forester and he focuses on Central European forest trees, with a few mentions of North American trees. He is not an academic or a scientist, and although there are footnotes, this book is as much about the author’s feelings as about scientific evidence. Sometimes he makes assertions that seem dubious – for example, that humans can subconsciously detect when trees are stressed and that this affects the humans’ well-being when they walk through an unhealthy forest. Some readers may also object to his frequent anthropomorphising of trees (for example, when trees are described as “cruel” or “ruthless” or “caring”) and his somewhat disorganised and repetitive prose. However, I found this a fascinating and enjoyable read and I ended the book with a renewed appreciation of trees.

I then read a lovely book about trees. The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben is an engaging, chatty account of how trees protect themselves and their young, adapt to challenging circumstances, fight for resources with other species, and share information, food and water with each other via a network of roots and fungi (the ‘wood wide web’). Trees can live for hundreds and even thousands of years and the author describes some amazing trees – for example, a single quaking aspen in Utah that covers 100 acres, with forty thousand trunks growing from the same roots, and a beech stump that was cut down five hundred years ago but has been kept alive all that time by neighbouring beeches feeding it sugar. The author is a German forester and he focuses on Central European forest trees, with a few mentions of North American trees. He is not an academic or a scientist, and although there are footnotes, this book is as much about the author’s feelings as about scientific evidence. Sometimes he makes assertions that seem dubious – for example, that humans can subconsciously detect when trees are stressed and that this affects the humans’ well-being when they walk through an unhealthy forest. Some readers may also object to his frequent anthropomorphising of trees (for example, when trees are described as “cruel” or “ruthless” or “caring”) and his somewhat disorganised and repetitive prose. However, I found this a fascinating and enjoyable read and I ended the book with a renewed appreciation of trees.

Finally, I read the first volume of John Mortimer’s very unreliable memoir, Clinging to the Wreckage. Mortimer, the author of Paradise Postponed and the creator of Rumpole of the Bailey, was a prolific playwright, screen writer and novelist, as well as a barrister and Queen’s Counsel. This volume describes him growing up as the only child of an eccentric and violent barrister, who refused to admit he was blind and insisted his long-suffering wife act as his scribe and guide dog. Young Mortimer attended Harrow and then Oxford, managed to avoid war service due to his own poor vision, joined the Crown Film Unit to produce propaganda films, then bowed to parental pressure to go into the law profession, all the while churning out a number of entertaining novels, plays and scripts. There is a lot of name-dropping, exaggeration and embellishment as he describes the literary, theatrical and legal worlds of London, but his anecdotes are usually amusing and engaging. In the introduction to this book, Valerie Grove accurately notes that he tends to portray himself as “a hapless and often bewildered onlooker, to whom stuff happens”. So, for example, he claims to be baffled when his twenty-year marriage to novelist Penelope Mortimer starts to crumble. He fails to mention his multiple extra-marital affairs or that he requested his wife have an abortion and sterilisation during her eighth pregnancy, and that while she was recovering from that operation, the poor woman learned that actress Wendy Craig had given birth to her husband’s son. (He also neglects to mention he was kicked out of Oxford when staff found he’d been writing ‘amorous’ letters to a schoolboy.) I puzzled over what all these women found attractive about him. It certainly wasn’t physical beauty, but perhaps they found his story-telling irresistible.

Finally, I read the first volume of John Mortimer’s very unreliable memoir, Clinging to the Wreckage. Mortimer, the author of Paradise Postponed and the creator of Rumpole of the Bailey, was a prolific playwright, screen writer and novelist, as well as a barrister and Queen’s Counsel. This volume describes him growing up as the only child of an eccentric and violent barrister, who refused to admit he was blind and insisted his long-suffering wife act as his scribe and guide dog. Young Mortimer attended Harrow and then Oxford, managed to avoid war service due to his own poor vision, joined the Crown Film Unit to produce propaganda films, then bowed to parental pressure to go into the law profession, all the while churning out a number of entertaining novels, plays and scripts. There is a lot of name-dropping, exaggeration and embellishment as he describes the literary, theatrical and legal worlds of London, but his anecdotes are usually amusing and engaging. In the introduction to this book, Valerie Grove accurately notes that he tends to portray himself as “a hapless and often bewildered onlooker, to whom stuff happens”. So, for example, he claims to be baffled when his twenty-year marriage to novelist Penelope Mortimer starts to crumble. He fails to mention his multiple extra-marital affairs or that he requested his wife have an abortion and sterilisation during her eighth pregnancy, and that while she was recovering from that operation, the poor woman learned that actress Wendy Craig had given birth to her husband’s son. (He also neglects to mention he was kicked out of Oxford when staff found he’d been writing ‘amorous’ letters to a schoolboy.) I puzzled over what all these women found attractive about him. It certainly wasn’t physical beauty, but perhaps they found his story-telling irresistible.

The best part of this book for me was his discussion of censorship. As a QC, he defended the publishers of Last Exit to Brooklyn and then the publishers of Oz magazine when they were charged with publishing “obscene” works. English law stated that a literary work was “obscene” if it “tends to deprave and corrupt those likely to read it”, although publishers could avoid conviction if the work was judged to have “artistic merit” and publication was in the “public good”. He successfully argued on behalf of the publishers of Last Exit that the book’s depiction of homosexual prostitution and drug abuse was so revolting that it would turn all readers away from these practices. He makes a number of sensible points — for example, that no-one is forced to read a book or watch a television show that they know will offend them, and that “if books had the effect claimed for them by the censors, every English country house would have a bloodstained butler in the library, dead with a knife between his shoulder blades.” His many examples of the Lord Chamberlain’s demands for script editing (“Wherever the word ‘shit’ appears, it must be replaced by ‘it’) would seem at first to be an amusing look at the olden days, except we have the current example of Roald Dahl’s books being bowdlerised (no mention of ‘fat’ or ‘ugly’ allowed anymore and ‘white’ and ‘black’ in ‘white with fear’ and ‘a black cape’ must be removed). The more things change, the more they stay the same.

December 30, 2022

My Favourite Books of 2022

What a year. At least it ended slightly better than it began, at least for me. However, 2022 was not a year when I read a lot of new novels. Looking at my book journal, I either didn’t read many new (to me) novels or I forgot to note them down. Probably my favourite novel was Gideon the Ninth — although having just finished its sequel, Harrow the Ninth, which was very much not my cup of tea, I’m afraid I am now done with this author and this series.

My favourite non-fiction books were Unfollow by Megan Phelps-Roper and Feminism for Women by Julie Bindel. I also liked The Edible Balcony by Indira Naidoo, which helped me re-establish my balcony garden. It was a good year for spinach, silverbeet, lettuce, sorrel, parsley and lavender, but some of my other plants struggled. Here is my entire annual crop of radishes, with a twenty cent coin for scale:

I don’t think I’ll be taking up professional radish farming any time soon.

My favourite books for teenagers and children included Sugar Town Queens by Malla Nunn, Are You There, Buddha? by Pip Harry, and Fly on the Wall by Remy Lai. All by Australian authors!

I’m hoping to be able to read more in 2023 and possibly even get some writing done. Here’s my pile of holiday reading:

I hope you all have a happy, relaxing holiday season and that 2023 brings you lots of good reading.

December 12, 2022

‘Gideon the Ninth’ by Tamsyn Muir

Gideon the Ninth, the first in the bestselling speculative fiction series, The Locked Tomb, written by Tamsyn Muir, is not the sort of book I would usually pick up. It’s described as weird, dark, science fiction horror, full of swords and skeletons and necromancy, which is not usually my cup of tea. However, I’d read a lot of hype about this book and was eventually drawn in by the tagline on the cover: “Lesbian necromancers explore a haunted gothic palace in space!”

This turns out to be misleading. There’s no sex, lesbian or otherwise, and almost no romance. Gideon, the point-of-view protagonist, isn’t a lesbian necromancer, although she is female and same-sex-attracted, as are several other characters. The word ‘lesbian’ doesn’t seem to exist in this world, possibly because the default in this world isn’t heterosexual relationships or male authority. Women can be soldiers, scholars, healers, powerful magicians and leaders, just as men can be, so that’s nice. The ‘in space’ part is also misleading — apart from a quick shuttle ride between planets and some passing references to battles going on outside their galaxy, there’s almost nothing in the book that is traditionally ‘science fiction’. So that’s also nice for me, because I don’t usually like science fiction.

There is a lot of Gothicism, though. Gideon is a maltreated teenage orphan with mysterious origins, brought up by the House of the Ninth, an ancient death cult on a planet in the furthest reaches of their galaxy. Gideon spends her time reading dirty magazines, hitting things with her sword, and trying to escape the planet so she can join their Emperor’s army. The only other person her age is Harrow, Reverend Daughter of the Ninth House, a skilled necromancer whose speciality is making skeletons move about. Harrow hates Gideon almost as much as Gideon hates her and they both seem utterly miserable. But when their Emperor summons Harrow and all the other House heirs to his First House, in order to appoint his next eternal, all powerful assistants, Harrow and Gideon are forced to work together, to travel across the galaxy to the First House and solve the Emperor’s mysterious challenges.

The book gets off to a slow start, but once Gideon and Harrow reach the decaying palace of the First House, I was completely engrossed in the story. I liked the atmospheric descriptions of the palace, with its crumbling terraces and overgrown conservatories and rotting rooms, staffed by an army of animated skeletons and ruled by three very odd priests. The House necromancers, each with their own rapier-wielding cavalier, aren’t given any guidance about what they actually need to do to become immortal Lyctors (‘I am certain the way will become clear to you without any input from us,’ says the main priest cheerfully), so there’s a lot of mystery and intrigue as clever Harrow and brave, reckless Gideon explore the palace to identify and solve all the puzzles. It becomes even more exciting when they realise a serial killer and/or malevolent supernatural force seems to be killing off the House necromancers and cavaliers, one by one, and they understand how deadly their tasks have become.

I found this book very intellectually challenging, I must say. Simply keeping track of the characters was difficult. They have names like ‘Palamedes Sextus, Heir to the House of the Sixth, Master Warden of the Library’, who is variously referred to as ‘Palamedes’, ‘Sextus’, ‘The Warden’, ‘The Sixth’ and ‘Master’, sometimes within the same scene. Fortunately, there was a list of characters at the front of the book, which I constantly referred to. I also needed to keep track of all the challenges, which involved various rooms, keys and secret symbols on doors, as well as try to figure out what was going on with the murders and disappearances. The plot twists are clever and surprising and usually make complete sense in hindsight, although if you’re the sort of reader who likes to figure out the answer to the mystery in advance, I should warn you that it is impossible to work this one out — we simply aren’t given enough relevant information and this world doesn’t follow our own rules. I did guess which characters were a bit dodgy, but my guesses as to what they were really doing were completely wrong.

This all makes the book sound very serious, but it’s actually extremely funny and imaginative and entertaining. This is because we see everything through the eyes of Gideon, an irreverent, impatient teenager who is quick to counteract any portentousness with rude jokes. In fact, her slangy, snarky voice, full of references to our own popular culture, is nothing like that of any of the other characters or even consistent with anything in their world. She has been brought up by ancient nuns on a distant planet, she doesn’t recognise the function of a bathtub or swimming pool, has never seen green vegetables or fish or the ocean, yet she describes something on her pillow as “like a chocolate in a fancy hotel”. How does she know about fancy hotels? Why does she make jokes using Tumblr memes? How did she even get access to pornographic magazines or aviator sunglasses on her planet? At first I thought Gideon must have dropped through some time-travelling portal from our world, but no, the author just does all this because she thinks it’s funny. It occasionally threw me out of the story, but mostly I shrugged and got on with enjoying the narrative twists and turns. Your tolerance for this sort of authorial self-indulgence may differ from mine.

Gideon’s anachronistic voice certainly seems to be the main reason this book has such mixed reactions to it, although there are some other flaws of pacing and world-building. It’s the author’s first novel and there were times when I thought the editing could have been more thorough. Still, it’s a hugely ambitious, entertaining, genre-mashing book that I think will appeal to readers who don’t usually read science fiction or horror – for example, Rivers of London fans. I’m looking forward to reading the sequel, Harrow the Ninth, although I have been warned it’s even weirder and more challenging than this one.

November 27, 2022

Miscellaneous Memoranda

I’m glad I deleted my Twitter account a few years ago. Perhaps the authors now leaving Twitter will turn to blogging? I’d like that. I like reading long, thoughtful, book-related posts, although of course, blog posts can also consist of miscellaneous snippets of articles and commentary and videos …

– This is worrying. American publishers are increasingly adding “morals clauses” to their contracts so they can terminate contracts and force authors to pay back advances if the author is accused of “immoral, illegal, or publicly condemned behavior”.

As the Authors’ Guild points out,

“individual accusations or the vague notion of ‘public condemnation … can occur all too easily in these days of viral social media.

Now publishers apparently want the ability to terminate an author’s contract for failing to predict how their words will be received by a changing public. This is a business risk like any other, yet publishers are attempting to lay it solely at authors’ feet. Worst of all, morals clauses have a chilling effect on free speech. A writer at risk of losing a book deal is likely to refrain from voicing a controversial opinion or taking an unusual stand on an important issue.”

– In the UK, publishing is in a “parlous state”, writes a pseudonymous publishing insider:

“just warning people off books isn’t sufficient. The author in question needs to be punished for their crime, be it transphobia, racism, misogyny or whatever. Never mind that we can all take offence at anything or nothing; that one person from a particular group who is offended by a story does not equal all people from that group being thus offended; that a simple way to not be offended is simply not to buy the book.

No, that is no longer enough. The author must be hounded on social media, their publishers & agents must be emailed, and the sinner in question must then atone for their sins by publicly apologising, “educating” themselves (which to me is the language of the gulag) and rewriting the book to remove the offence…

To know that so many people live in fear of saying the wrong thing in an industry which should be celebrating dissent and freedom of speech is something I find deeply shocking. It has come about because a minority of people with the loudest voices have bullied their way into the publishing world and insisted that only they are on the path of true righteousness.”

– Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, five brave, outspoken speech therapists have been jailed for publishing a series of children’s books featuring sheep fighting back against marauding wolves:

“Judge Kwok said in his verdict that ‘children will be led into the belief that the PRC Government is coming to Hong Kong with the wicked intention of taking away their home and ruining their happy life with no right to do so at all,’ referring to the People’s Republic of China.

Defendant [Melody] Yeung quoted U.S. civil rights leader Martin Luther King saying ‘a riot is the language of the unheard.’

‘I don’t regret my choice, and I hope I can always stand on the side of the sheep,’ Yeung said.”

– Looking for Alibrandi is thirty years old this year and Melina Marchetta discusses it here. There’s also an interesting new theatre adaptation of the book, written by an Indian Tamil migrant, who grew up in Kuwait and moved to Perth as a teenager, and starring Chanella Macri, an Italian Samoan actor, as Josie Alibrandi.

As Pia Miranda, who played Josie in the film version, says,

As Pia Miranda, who played Josie in the film version, says,

“It’s a migrant story that transcends being Italian. And a lot of the people that have spoken to me over the years [and said] that it means a lot to them are from different backgrounds, whether it be people from Muslim or Asian backgrounds.”

– Anne Tyler has a new novel out, French Braid. I’m always happy to see an interview with her, even though I suspect she hates doing them. Here she discusses, among other things, ‘cancel culture’ and cultural appropriation and how she’s an accidental novelist:

“I never planned to be a writer at all. For years, maybe even today, sometimes I think, ‘What exactly am I going to do with my life? What is my career going to be? I’m only 80, for God’s sake!’”

– Fans of Octopolis will enjoy this update on the residents’ behaviour: “Sometimes This Octopus Is So Mad It Just Wants to Throw Something”. I highly recommend Peter Godfrey-Smith’s book on octopus intelligence (and belligerence), Other Minds: The Octopus and the Evolution of Intelligent Life.

– The New Yorker has a fascinating article on the creators of the Choose Your Own Adventures books.

– Look at this amazing Ghibli quilt! Look at Calcifer and Jiji and No-Face and all the little soot sprites! She’s also made a Totoro quilt.

– I’m not a fan of John Hughes films, except for Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and only because of the museum scene, so I enjoyed this thoughtful article on Ferris, Cameron and the power of art museums. And yes, this IS related to books, because the painting Cameron gazes at also features in Rebecca Stead’s Liar & Spy. If you clicked on the video in the article, you’re probably now humming the lovely instrumental music from that scene, so here it is, The Dream Academy’s cover version of Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want:

August 1, 2022

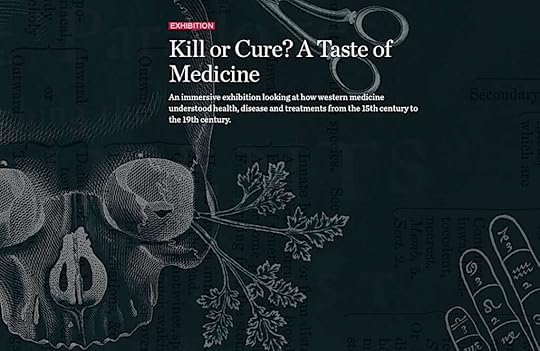

‘Kill or Cure? A Taste of Medicine’ Exhibition

This new exhibition at the State Library of New South Wales looks great.

“From the influence of the stars and the phases of the moon, to healing chants and prayers, to the knife-wielding barber-surgeon and game-changing scientific experiments, Kill or Cure? takes you behind the curtain of western medicine’s macabre history.

Explore our many treatment rooms with instruments that will make your skin crawl. Hear quack doctors spruiking dangerous cures from behind the interactive walls. Meet the bloodletting man and learn why veins were opened to restore health.

The Library’s extensive rare books collection reveals some of the powerful and enduring ideas from western medicine that have since been debunked, and those we take for granted today.”

Lots of fascinating, gory exhibits about bloodletting, leeches, plague and scurvy! It’s free and will be at the State Library’s Exhibition Galleries in Shakespeare Place, Sydney until January 2023.

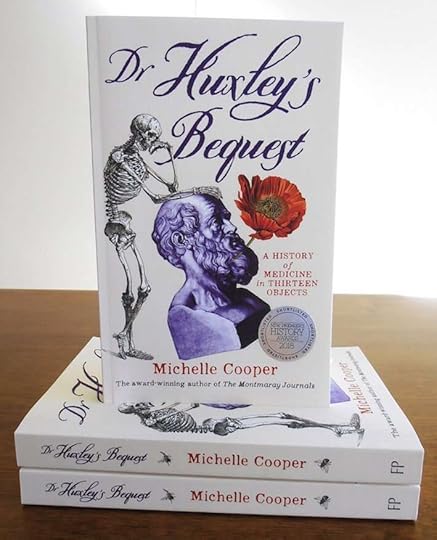

And after you’ve visited the exhibition, if you want to learn even more about the weird and wonderful history of medicine, why not read (or re-read) Dr Huxley’s Bequest: A History of Medicine in Thirteen Objects?

July 17, 2022

Further Thoughts on Quilting and Writing

I’ve been struggling with writing this year (and indeed last year, and the year before), which is largely because I’ve been working in a hospital during a pandemic, so I’ve been constantly tired and stressed. But even when I’ve carved out enough time and energy to sit down and focus on my latest manuscript, getting each chapter finished has been a colossal effort.

Now, writing has never been easy for me (I’ve always given a hollow laugh whenever a reviewer has mentioned my “effortless prose”) but it seems to be getting more difficult. Shouldn’t it be plain sailing now that I’ve had five books published? Shouldn’t experience be useful? I’ve got everything for this novel-in-progress plotted on a spreadsheet. I know a lot about the characters. I have a reasonable vocabulary (and possess a thesaurus) and I understand how to construct a range of sentence types. I know what needs to happen on the page.

But I recently realised that I’ve been expecting each sentence, each paragraph, each chapter, to be close to perfect before I can move on to the next section. This is why I’ve re-written the first chapter seventeen times (in fairness to myself, it is now an excellent opening chapter). But no wonder everything’s progressing so slowly! It’s really not surprising that I dread sitting down at the computer and opening up the document.

I needed a mental re-set, so I put aside my writing and made a quilt. Usually the quilts I make have traditional geometric patterns, because this appeals to my nerdy maths brain:

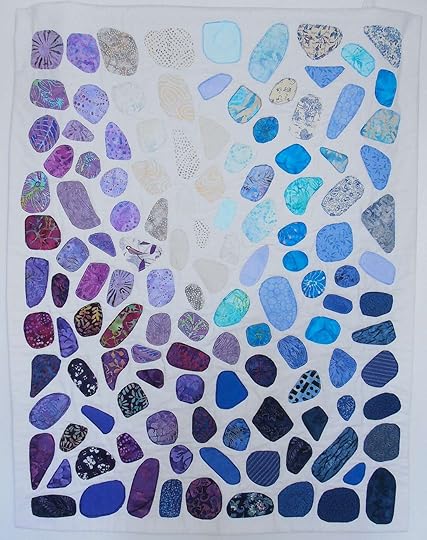

This latest quilt, though, is a Seaglass Quilt. I took an online course at Exhausted Octopus to learn the technique. It was a clear, useful course, but they don’t provide any pattern. The size, shape and placement of pieces are all improvised. Instead of traditional piecing and hand-quilting, there’s raw edge appliqué with fusible adhesive backing, and Free Motion Quilting, and facing rather than binding. The course even suggests basting WITH SAFETY PINS. This was all totally out of my quilting comfort zone.

But this quilt was so much fun to make! The course suggested making a small quilt first to try the techniques. I ignored this and made a big quilt to hang on my bedroom wall, so it did take about a week to finish, mostly because my very old sewing machine said ‘Nope!’ to Free Motion Quilting, so I used straight stitch around each of the 126 seaglass pieces. Some of the fused pieces fell off the background fabric before I’d gotten around to sewing them, so I pinned them back on, often in a slightly different position to where they were meant to go. At one point I decided I didn’t like the colour of a piece I’d already sewn so I sewed another piece directly on top. I just used whatever thread I had, sometimes to match the seaglass pieces, sometimes contrasting, depending on what I thought looked best at the time. The safety pin basting mostly worked but I did end up with some wrinkles in the middle:

But that was okay, because it looks like ripples in the sand around the pieces of seaglass. And the edges of the quilt aren’t perfectly straight, because some of my facing was a bit uneven, but that’s also okay. It’s organic and free-flowing. There are scraps of fabric that remind me fondly of past sewing projects.

It’s colourful and cheerful and it makes me happy when I look at all of it, including the imperfections.

There’s a lesson in there somewhere for perfectionist writers. Go with the flow. It won’t be perfect on the first draft, or the seventeenth draft, but a completed project will bring you satisfaction and possibly even joy.

You might also be interested in reading: