Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 24

September 17, 2013

Science Reads: ‘Unweaving the Rainbow’ by Richard Dawkins

Today in Science Reads, I’d like to talk about a book that argues that scientific knowledge enhances, rather than destroys, our sense of wonder about the universe. In Unweaving the Rainbow, Richard Dawkins has written a rebuttal to John Keats’s idea that Isaac Newton “destroyed all the poetry of the rainbow by reducing it to the prismatic colours”. For the most part, Dawkins does this clearly, effectively and with a sense of humour. There are fascinating discussions about astronomy, sound perception, forensic DNA testing and how genetics can reveal information about the ancestral environment of a particular species. My favourite chapter was about how Uncanny Coincidences (for instance, your horoscope correctly predicting your future, or a TV magician making wristwatches stop or start with the power of his mind) are usually not very uncanny at all, once you use probability mathematics and scientific logic to work out how likely it is that these events will occur.

Dawkins also discusses how scientists can sometimes get a bit carried away with using ‘poetical writing’ to convey their ideas, at the expense of clarity and accuracy. This was the part of the book where I felt Dawkins forgot his central thesis and got a bit carried away himself, on tangents that were not very interesting. Unfortunately, he also devotes a few pages of this book to one of his pet peeves – “feminist bullies” who apparently try to prevent young women from studying science because it’s the “brainchild of white Victorian males”. Now, as a woman who has studied science and worked in a couple of science-related fields, I feel I have a bit more personal experience in this area than Richard Dawkins, and I have to say that all the people who tried to discourage me from science were not feminists, but sexist men, starting with my Year Eleven Physics teacher, who informed us that girls didn’t have the right sort of brains to understand Maths and Physics1. This attitude was shared by male staff teaching Pure Mathematics at the university I subsequently attended.2 In fairness to Dawkins, Unweaving the Rainbow was first published in 1998, and his more recent books, such as The God Delusion, seem far less anti-feminist. Perhaps his views have matured, or perhaps his publishers pointed out to him that women read books about science, too, and that annoying the people who have bought his book is a bad business strategy.3 Anyway, this is a small part of an interesting, entertaining and often inspirational book, which I recommend with some reservations.

Tomorrow in Science Reads: Knowledge is Power: How Magic, the Government and an Apocalyptic Vision inspired Francis Bacon to create Modern Science by John Henry.

_____

I would have made a rude gesture at this Physics teacher from the stage of our school assembly hall the following year, when I was awarded the school prizes for Physics and Chemistry, but fortunately for everyone, he’d retired by then. ↩

Although I should point out that the (male) Applied Maths lecturers were so enthusiastic and fun that I briefly considered becoming a statistician. And my (male) Chemistry professor was similarly encouraging. ↩

I don’t think his views have matured very much, given some of the things Dawkins has said in response to women being sexually harassed and assaulted at atheist conferences. ↩

Science Reads: ‘I Wish I’d Made You Angry Earlier: Essays on Science, Scientists and Humanity’ by Max Perutz

Our new Prime Minister has just announced his Cabinet, and for the first time since 1931, the Australian government does not have a Minister for Science. (After all, who needs scientists when we have the Pope to decide how the universe works? Just ask Galileo how well that went.) But here at Memoranda, we love science, so we’ve unilaterally declared this week ‘Science Reads Week’. It’s already Tuesday, so it’ll be a fairly short week, but each day for the rest of the week, I’ll be posting about some interesting science reads.

Today, I’d like to recommend I Wish I’d Made You Angry Earlier: Essays on Science, Scientists and Humanity by Max Perutz, who won the Nobel Prize for figuring out the structure of haemoglobin (which is the molecule in our red blood cells that transports oxygen around our bodies) and myoglobin (which does a similar thing inside muscles). Max Perutz also helped found the European Organisation for Molecular Biology, was an excellent science communicator, and seems to have been a genuinely nice person. John Meurig Thomas, for example, wrote:

“Perutz was a gentle, kindly and tolerant lover of people (particularly the young), passionately committed to social justice and intellectual honesty; and the warmth of his personality radiated a sense of human goodness and decency which induced others to behave sanely, especially because he exuded an inner excitement that stems from a love of knowledge for its own sake.”

In this collection of science-themed essays and book reviews, Perutz writes eloquently about the development of chemical weapons during WWI, atomic weapons during WWII, and biological weapons during the Cold War. He also discusses a number of important twentieth-century scientists, most of whom he knew personally, including Peter Medawar (whose work on immunology led to successful organ transplants), Albert Szent-Györgyi (who isolated Vitamin C), Linus Pauling (who, among other achievements, worked out how molecules were held together by chemical bonds, and identified that amino acids had alpha-helix structures, which helped Watson and Crick figure out that DNA had a double-helix structure), Dorothy Hodgkin (who figured out the structure of cholesterol, insulin and penicillin, and won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964) and Lise Meitner (who identified the splitting of the uranium atom and named it ‘fission’, although it was her male colleague who was awarded the Nobel Prize for their work). There are also powerful arguments for human rights, for freedom of expression, and for women to have the right to control their own fertility with contraceptive drugs and safe abortions, as well as a thoughtful exploration of whether an accident at a UK nuclear energy station led to long-term environmental damage and health problems in the local population.

However, my favourite piece was about Perutz’s experiences during WWII. He was born and raised in Vienna, but moved to England to study chemistry at Cambridge in the 1930s. When the Nazis invaded Austria in 1938, he was unable to return home due to his Jewish ancestry. His parents managed to escape Austria and join him, but after war was declared, Perutz and his father were both interned by the British as ‘enemy aliens’. Even though Perutz was passionately anti-Nazi and had just been awarded a PhD from Cambridge (which you’d think would be pretty useful for the war effort), the British government decided to send him to a prison camp in the wastelands of Canada. After further adventures and with the help of his British scientist friends, he made it back to England, where he spent the war working for a very eccentric civilian named Geoffrey Pyke. Among Pyke’s pet projects was the development of bullet-proof ice, reinforced with wood pulp, called pykrete, although the plan to use it to make sea-borne aircraft carriers sank (literally). Pyke also came up with the bright idea of “the construction of a giant tube from Burma into China – much easier than building a road . . . Through this tube, Allied men, tanks and guns were to be propelled by compressed air.” Not even Churchill supported this ridiculous scheme, and Perutz eventually “returned to Cambridge, sad at first that my eagerness to help in the war against Hitler had not found a more effective outlet, but later relieved to have worked on a project that at least never killed anyone – not even the Chief of the Imperial General Staff [who had been injured when a bullet rebounded off a block of pykrete during one of Pyke's ill-conceived demonstrations].”

Of the thirty-seven essays in the book, I think only two require readers to have some specific scientific knowledge (one is about haemoglobin’s structure, the other about how X-Ray crystallography developed into a useful tool for analysing biological molecules). For the most part, this is an accessible, engaging and fascinating book about science and its effects, good and bad, on humankind in the twentieth century.

Tomorrow in Science Reads: Unweaving the Rainbow by Richard Dawkins

September 10, 2013

Books To Make You Laugh

A lot of Australians are currently feeling very depressed after one of the longest, most vacuous, federal election campaigns in recent memory1. What we need now are some books to make us laugh2. Here are five books that have made me laugh out loud (or at least produced embarrassing muffled snorting noises, if I happened to be reading them on public transport).

1. My Family and Other Animals by Gerald Durrell, featuring the eccentric Durrell family and the ridiculous situations they find themselves in, often caused by their various dogs, birds, snakes, scorpions and other animal companions. For example, here’s Roger the dog’s reaction to Mother’s elaborate new bathing-costume:

“He seemed to be under the impression that the bathing-costume was some sort of sea monster that had enveloped Mother and was now about to carry her out to sea. Barking wildly, he flung himself to the rescue, grabbed one of the frills dangling so plentifully round the edge of the costume and tugged with all his strength in order to pull Mother back to safety. Mother, who had just remarked that she found the water a little cold, suddenly found herself being pulled backwards. With a squeak of dismay she lost her footing and sat down heavily in two feet of water, while Roger tugged so hard that a large section of the frill gave way. Elated by the fact that the enemy appeared to be disintegrating, Roger, growling encouragement to Mother, set to work to remove the rest of the offending monster from her person . . . “

2. Saffy’s Angel by Hilary McKay, which I have previously gushed about here. The scene in which the siblings drive to Wales is especially funny.

3. Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris, and specifically, the story entitled Jesus Shaves, in which Mr Sedaris attends French classes in Paris, and his fellow students attempt to explain Easter, in their extremely limited French, to a Moroccan student:

“The Poles led the charge to the best of their ability. ‘It is,’ said one, ‘a party for the little boy of God who call his self Jesus and . . . oh, shit.’ She faltered and her fellow countryman came to her aid.

‘He call his self Jesus and then he be die one day on two . . . morsels of . . . lumber.’

The rest of the class jumped in, offering bits of information that would have given the pope an aneurysm.

‘He die one day and then he go above of my head to live with your father.’

‘He weared of himself the long hair and after he die, the first day he come back here for to say hello to the peoples.’

‘He nice, the Jesus.’ “

Unable to translate complicated phrases such as “to give of yourself your only begotten son”, they end up talking about chocolate, which is delivered, of course, by “the rabbit of Easter”. Or rather, as it turns out, the bell of Rome.

There’s also a very funny story about young David’s battles with his speech therapist (although, as a trained speech pathologist, I have to emphasise that we’re not like that at all now).

4. King Dork by Frank Portman, which I don’t have in my possession, so I can’t provide any quotes, but I remember becoming helpless with laughter over the effort the teenage boys put into their band names and album concepts. Favourite band name: We Have Eaten All The Cake. (Unfortunately they don’t put as much effort into writing songs or rehearsing, so their first big gig is a disaster. I should also point out that parts of this novel, especially the conclusion, are not funny at all, although it’s also completely plausible that the narrator and his friend would be as unconcerned about these particular issues as they are.)

5. Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons, which I have written about here, is so full of hilarity that it’s impossible to choose just one scene. The cows, named Graceless, Pointless, Feckless and Aimless? Adam clettering the dishes with his twig? The Starkadders pushing each other down the well? The Quivering Brethren’s hymn-singing being conducted by the poker-wielding Brother Ambleforth? Seth lounging in doorways, with his shirt unbuttoned? Mr Mybug’s ludicrous theories about how all the Brontës’ novels were actually written by Branwell? Or those “finer passages”, helpfully marked by the author with one, two or three stars?

Of course, humour is completely subjective and dependent on context, so it’s possible you won’t find these books as amusing as I did. Please feel free to add your own funny book recommendations in the comments. We need all the laughter we can get around here.

_____

I couldn’t even bear to listen to the vote counting on the radio, so I spent Saturday night watching Series Two of The Thick of It . For those not familiar with this BBC production, it’s about a stupid, bigoted and hypocritical MP named Abbot, who’s inexplicably promoted far beyond his levels of competence into the Cabinet. Each episode involves his spin doctors running around, desperately trying to cover up his blunders. ↩

so we don’t cry. ↩

September 2, 2013

Writing About Place

The book I’m currently trying to write is set in my neighbourhood, which is a new experience for me. If I needed to know the details of a particular location when I was writing the Montmaray books, I either had to make it up from scratch or travel through time and space in my TARDIS1 to examine the place. Now, though, I can simply go for a short walk down the road and take a few photos.

This saves a lot of time and effort, but I’ve also become aware of how much I’m editing my setting. For example, I’m deleting the graffiti and most of the roadside litter and that ugly sixties office block on the corner, and concentrating instead on the lovely Victorian and Art Deco architecture and the manicured cricket pitch and all the majestic old trees. When (if?) I ever finish writing the book, I plan to draw a map, so that readers can walk along the same streets as my characters and visit the same buildings2. But while my book’s setting is ‘true’ for the most part, it’s certainly not the whole truth and nothing but the truth.

I was thinking about this because a while back, I saw an American blogger3 exclaim that, thanks to Melina Marchetta‘s novels, the blogger now knew exactly what the inner western suburbs of Sydney were like. And when I read that, I flapped my hands at my computer screen and cried, “No, no, it’s not like that at ALL!” Now, I must admit, Melina Marchetta would probably not classify me as a TRUE Inner Westie. I was not born at King George V Memorial Hospital for Mothers and Babies (although I did once work there, or at least visit it often while I was employed at the adjacent hospital), I’ve only lived in the inner west for about twenty-five years, and (horror of horrors) I don’t drink coffee. On the other hand, I have lived in the same suburbs as Josephine Alibrandi and Francesca Spinelli and Thomas Mackee (in fact, they filmed part of Looking for Alibrandi in my street) and most of the places mentioned in the novels are very familiar to me.

AND YET. Melina Marchetta’s Inner West is not my Inner West. For example, in Melina Marchetta’s Inner West, nearly everyone is of European ancestry, goes to a private school and is Catholic (nominally, not necessarily in an attending-Mass-each-Sunday way). Hardly anyone is Aboriginal Australian or Asian-Australian or Pacific-Islander-Australian. Gay and lesbian people exist only to show how tolerant (or temporarily intolerant) the main characters are. And no one seems to use contraception (and when the inevitable pregnancy results, no one even mentions the possibility of the existence of abortion). Now, of course, there are plenty of heterosexual, pregnant Italian-Australians in the Inner West. But in the ‘real’ (that is, my) Inner West, there are also lots of people without European ancestors. There are lots of atheists. It is true that there are several expensive and/or religious private schools in the area, but nearly all young children go to (fee-free) state primary schools, and among the most prestigious, difficult-to-get-into high schools are two (fee-free) state schools, Fort Street High and Newtown High School of the Performing Arts. Also, a local council survey a few years back found that about 21% of residents identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. More than one in five people! (Admittedly, the council area did not include Leichhardt and did include some parts of the very gay inner east of Sydney, but I should also point out that the inner west hosts the headquarters of Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, plus a number of gay pubs and clubs; that local businesses routinely stock the free LGBTQ community newspapers and the local cinema hosts Queer Screen; and that Leichhardt used to be known as Dyke-Heart due to the large number of lesbian couples who lived there.) Oh, and Australia’s oldest, most famous, feminist-run women’s health clinic, which used to provide abortion services and still offers abortion counselling, is right in the middle of Leichhardt.

This isn’t to say that Melina Marchetta’s version of the Inner West is ‘wrong’ – in fact, I admire her vivid and evocative snapshots of the places that I know and love. But, as with any snapshot, there’s far more outside the frame than captured within it, and the positioning of the frame itself depends on the person holding the camera. What I need to figure out as I try to write my own book is whether I’m holding my camera up to the most important, useful and authentic scenes, or letting my own unexamined preferences frame each shot.

My Rainbow Neighbourhood. ACTUAL RAINBOW.

_____

Note: I don’t actually have a TARDIS. What I actually had to do was look at lots of old maps and photos and diaries. ↩

Look, Simmone Howell has done the same for her novel, Girl Defective! ↩

I honestly can’t remember which blogger, otherwise I’d link to the blog post. ↩

August 13, 2013

Yet More Of What I’ve Been Reading

I tend to blog only about books I like1, because why would I want to draw attention to books I hated? But until now, I’ve avoided discussing books by contemporary Australian authors, even books I’ve loved. I was worried readers would think I was only praising the book because I was friends with the author. This doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, now that I think about it (especially as I don’t actually know many other authors). So I’ve decided that I will talk about these books from now on, but I’ll add a disclaimer explaining my relationship with the author, so readers can judge for themselves whether my opinion of the book is impartial or not.

(Note to self: Why am I bothering to go on about this? Hardly anyone reads this blog, anyway. And those who do are well aware that Memoranda is not The New York Review of Books.)

(Note to any Australian authors who may be reading this: If I haven’t written glowing praise of your latest work, just assume I haven’t read it, which is almost certainly true.)

On to what I’ve been reading:

Girl Defective by Simmone Howell

DISCLAIMER: I’ve never met Simmone Howell, but she once asked me to write a guest post for her blog and we exchanged emails about this and we sent each other copies of our novels (this is like exchanging business cards, but involves a lot more reading). I loved her first novel, Notes from the Teenage Underground; I liked-with-reservations her second novel, Everything Beautiful.

I think her third novel, Girl Defective, is brilliant, and I’m predicting it’ll be on all the award shortlists next year (oh, I hope I haven’t jinxed it now). This is a smart, funny, warm-hearted novel about a flawed but loving family, made up of teenage narrator Sky, her odd little brother Gully, and their alcoholic dad, who runs a record shop2. Sky’s mother has abandoned them, and, as if Sky didn’t have enough to do looking after Gully, she’s worried she’s losing her only friend, a cute boy has started working at their shop, and mysterious graffiti art featuring a missing girl has begun appearing all over their suburb. There was so much I liked about this book. Gully’s detective work! The vivid portrait of St Kilda, which is almost a character in itself. All the great lines (“Sending Nancy texts was like sending dogs into space. Nothing came back.”) That Sky’s discoveries about love are as much about family and friendships as about sex. That the interlocking mysteries are revealed at exactly the right pace, without any implausibly neat endings. That it’s gritty and dark, but not without hope. In fact, it’s a testament to how good this novel is that it involves a variation of one of my least favourite YA tropes ever (Slutty Self-Destructive Teen Girl Dies So That Teen Boy Can Grow Up And Learn Stuff About Life) and yet I still loved it. A warning for SqueakyCleanReads fans: this book probably isn’t for you, given all the sex and drugs and rock-and-roll, some of it under-age. For other YA readers, Girl Defective is highly recommended. It came out in Australia earlier this year, and will be published by Atheneum in the US next year.

Births, Deaths, Marriages: True Tales by Georgia Blain

DISCLAIMER: I’ve never met, talked with or emailed Georgia Blain, but we were once meant to appear on the same panel discussing YA literature at a literary festival. The organisers inexplicably scheduled the YA talk for nine o’clock on a Sunday morning, then required bookings from anyone planning to attend, then were surprised at the subsequent lack of bookings and cancelled the event at the last minute. I was quite relieved about this because a) they’d neglected to tell me what, exactly, we were meant to be discussing (surely the existence of YA literature is not, in itself, a topic of discussion), and b) I didn’t really want to get up at dawn on a Sunday to trek across Sydney. So, that is the sum total of my connection to Georgia Blain, who, for non-Australian readers, is a well-known Serious Literature person who’s written one YA novel, which I didn’t like much3, plus some grown-up fiction and non-fiction.

Births, Deaths, Marriages is a thoughtful and moving account of the author’s childhood, which looked perfect from the outside (a bright, pretty child with rich and famous parents, living in a lovely house in a beautiful part of Sydney) but was actually riven with conflict. Her father seemed to have some sort of obsessive compulsive disorder and was verbally and physically abusive (“it was the threat of what he might do that kept us tiptoeing, scared, around him”) and her elder brother got caught up in a life of crime and drug abuse, was diagnosed with schizophrenia and died of an overdose. Her mother, the writer and broadcaster Anne Deveson, was a talented, strong-minded individual and a passionate feminist, but it took her years to decide to leave her abusive marriage, and this book is particularly good at describing the conflicting loyalties and societal pressures that turn us all into hypocrites: “I had absorbed my mother’s success, her ideological beliefs, and her years of appeasing my father in equal measures . . . we are all capable of holding many selves in argument with each other.” Not surprisingly, given the chaos and trauma of her early years, the author turns into a perfectionist adult, over-analysing everything, including her happiness. Her relationship with her loving partner is fraught; when she achieves her longed-for pregnancy, she spends the whole time panicking about how she’ll cope with the birth, then is overwhelmed by the reality of caring for a helpless infant. I was really impressed with both the quality of the writing and the brutal honesty involved in this memoir, although I couldn’t help wondering how those close to the author felt about being the subject of her gaze. (Of course, she wonders about this at length, too: “How can I write about the people I know? What gives me the right to expose them?” But then she does it anyway. Although she’s much harder on herself than on anyone else still alive.) Recommended for those who like memoirs, especially those interested in the lives of Australian women.

Oh, good, I don’t have to write any more disclaimers, because the writers are all either dead, or living on the other side of the planet.

The Flight of the Maidens by Jane Gardam

This was a great coming-of-age novel set in post-war England, about three Yorkshire schoolgirls who win scholarships to university. One is a Jewish refugee who escaped Germany in 1938 and has no idea if the rest of her family survived the Holocaust. Another is a doctor’s daughter wondering how to sustain her relationship with a working-class boy. Meanwhile sweet, innocent Hetty, who never expected to get into university, worries about her academic ability, struggles to become independent of her smothering, tactless mother, and falls in love with a very unsuitable aristocrat. Really, there’s enough in any one of these girls’ stories for an entire novel, and so the author resorts to leaving some very big gaps in the narrative, which didn’t always work for me. However, I loved the emotional honesty in the descriptions of the family relationships and enjoyed all the clever, sharp descriptions. For example, Hetty, holidaying on a farm, observes “a brindled cat and kittens [which] lay in a cardboard box by the fender, the kittens feeding in a row like a packet of sausages . . . Their eyes, still shut, bulged under peanut lids.” But this is Jane Gardam, so you know not to expect sentimentality, and sure enough, two paragraphs later, a lamb has died and “the cat started eating it. Still warm, but they know. It’s Nature. Now, what’s wrong with Hetty? . . . She’s gone white.” Poor Hetty. Anyway, this is a very good read, as is Bilgewater, another coming-of-age novel by the same author.

A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood

Yes, I do actually read books written by men. I picked this up because I recently watched (and liked) the film by Tom Ford. This novel was beautifully written, with a lot of insightful commentary on relationships, ageing, death and grief, as well as some sharp satire targeting American consumer culture and 1960s homophobia. Unfortunately, there was also some really vile misogyny, and I wasn’t sure whether this was purely the opinion of the protagonist (a clever and endearing man, whom we’re meant to admire) or of the author as well. I suspect the latter. The writing was otherwise wonderful – lucid and often very funny – so I will probably read some more of this author’s work – perhaps the book that inspired the film, Cabaret. I must say, though, the film version of A Single Man had so little in common with the book that I’m surprised the film-maker gave his work the same title. (The film, for those who haven’t seen it, looks like a glossy fashion advertisement, so I’m not sure Tom Ford noticed the anti-consumerist message of the book at all. The film also gives the main character an entirely different story – the main character plans his death, which focuses his attention on all the beauty and love that remains in his life, despite the loss of his partner.)

The Works of Emily Dickinson

She goes on about God and Death a little too enthusiastically for my tastes, but she really could pack a punch into a quatrain, couldn’t she? I hadn’t read many of her poems before, and I was knocked sideways by the power of the images she conjured. Some of my favourite poems in this collection were The Inevitable, Childish Griefs, A Thunder-Storm, Apocalypse and Loyalty.

_____

The exception being my Dated Books series. ↩

Yes, records. Those dusty round vinyl things full of music that people used to play in the olden days. Actually, the shop reminded me of Championship Vinyl in High Fidelity . ↩

Darkwater, which involved one of my least favourite YA tropes ever (see above), a bland protagonist with almost nothing at stake, a mystery so obvious that even I’d figured it out within the first few chapters, and some really clunky expository dialogue. However, it also contained some beautiful descriptive writing and a great depiction of a mother-daughter relationship. And lots of readers loved it, and it was a CBCA Notable Book, so check it out if you think it sounds like your sort of book. ↩

August 6, 2013

Emily Dickinson, Patron Saint of Introverts

I’m nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us – don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody!

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog!

July 30, 2013

First Lines

The Atlantic recently asked some writers about their favourite first lines in literature. As Joe Fassler reports, “The opening lines they picked range widely in tone and execution – but in each, you can almost feel the reader’s mind beginning to listen, hear the inward swing of some inviting door.” I especially like the opening of Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White:

“Where’s Papa going with that axe?” said Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast.

You know right from the start that it’s all going to end in tears, don’t you?

Here are some more of my own favourites. I think it’s good to be told up front exactly what sort of book you’ve picked up:

We think it our duty to warn the public that, in spite of the title of this work and of what the editor says about it in his preface, we cannot guarantee its authenticity as a collection of letters: we have in fact, very good reason to believe it is only a novel.

Les Liaisons Dangereuses, or Letters Collected in One Section of Society and Published for the Edification of Others by Choderlos de Laclos

It’s also nice when an author explains all that we need to know about the protagonist:

The education bestowed on Flora Poste by her parents had been expensive, athletic and prolonged; and when they died within a few weeks of one another during the annual epidemic of the influenza or Spanish Plague which occurred in her twentieth year, she was discovered to possess every art and grace save that of earning her own living.

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons

Although this can sometimes be done just as effectively in half the words:

I planned my death carefully; unlike my life, which meandered along from one thing to another, despite my feeble attempts to control it.

Lady Oracle, probably Margaret Atwood’s funniest book

Or even fewer words:

I am a man you can trust, is how my customers view me.

A Patchwork Planet by Anne Tyler

And sometimes, an author’s first line not only tells us a lot about the protagonist, but conveys an essential truth about literature:

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversation?”

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

“The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo . . .”

July 23, 2013

Madeleine St John

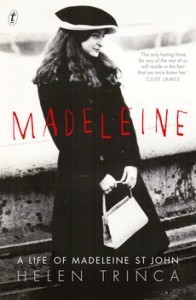

Earlier this year, I enjoyed The Women in Black, Madeleine St John’s first novel, and became interested in learning more about this writer. I had vague memories of seeing interviews with her after she became the first Australian woman to be short-listed for the Booker Prize, for her third novel, The Essence of the Thing. She insisted at the time that she wasn’t Australian at all, she disparaged the existence of literary prizes and she claimed to loathe every second of this Booker-related publicity, and I remember thinking she was protesting a tad too much. And now, having just read Helen Trinca’s biography of the novelist, I’ve learned that, in fact, Madeleine St John was absolutely thrilled at all the attention. It was the highlight of her life – a life that, according to this biography, was desperately sad and bitter. She had a troubled relationship with her cold, autocratic father, the Australian politician Ted St John, and her alcoholic mother killed herself when Madeleine was twelve years old. This seems to have led to a lifelong state of insecurity. Her biographer notes,

Earlier this year, I enjoyed The Women in Black, Madeleine St John’s first novel, and became interested in learning more about this writer. I had vague memories of seeing interviews with her after she became the first Australian woman to be short-listed for the Booker Prize, for her third novel, The Essence of the Thing. She insisted at the time that she wasn’t Australian at all, she disparaged the existence of literary prizes and she claimed to loathe every second of this Booker-related publicity, and I remember thinking she was protesting a tad too much. And now, having just read Helen Trinca’s biography of the novelist, I’ve learned that, in fact, Madeleine St John was absolutely thrilled at all the attention. It was the highlight of her life – a life that, according to this biography, was desperately sad and bitter. She had a troubled relationship with her cold, autocratic father, the Australian politician Ted St John, and her alcoholic mother killed herself when Madeleine was twelve years old. This seems to have led to a lifelong state of insecurity. Her biographer notes,

“Over and over, she would draw people in with her loving charm, intelligence, creativity and high values. But before long, she would create a crisis or an argument, driving away friends who were left bewildered by her behaviour. Then, after a break, a card or phone call would signal a desire to resume relations. All her life, Madeleine made sure she rejected others before they could abandon her, then hauled them back on her terms.”

while her younger sister, Colette, said,

“She just had this talent for alienating people and it didn’t matter what you did. That’s what she did with relationships, she was terrified of intimacy.”

She struggled with depression most of her life, trying various forms of psychotherapy, medication and religion in an attempt to relieve the anguish, then died alone, aged sixty-four, of lung disease. It must be said that there isn’t much evidence of Madeleine’s “loving charm” in this biography, but the charm must have existed, otherwise why else would so many intelligent, creative and successful people have wanted to be her friend in the first place?1 Yet she was a terrible snob, keeping a copy of Debrett’s on her bedside table and constantly reminding people that her family was in it (her father was distantly related to Baron St John of Bletso). Perhaps that’s why she was so good at describing people in her novels – she’d spent so long observing other people’s language and manners in order to determine their ‘true’ position in society and work out whether they were worthy of her attention. And perhaps her “high values” help to explain why her first novel wasn’t published till she was in her fifties – perhaps she felt that none of her fiction was good enough to show anyone else until then.2 Michelle de Kretser gave this biography a lukewarm review in The Sydney Morning Herald, saying it was “carefully researched” but not “a work of literature”, and anyway, Madeleine St John was only a “minor writer”3, but I found it fascinating.

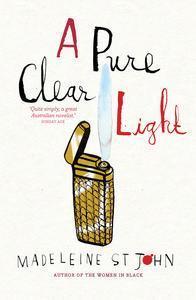

However, I think Madeleine St John’s novels are even better, and I especially recommend A Pure Clear Light, her second novel. Ostensibly, it’s the story of a pair of middle-class Londoners (complete with three beautiful children, a Volvo and summers spent in France) whose marriage starts to unravel when the husband begins an affair, but it’s actually a chance for the author to poke fun at some very shallow, hypocritical people. Simon, the adulterous husband, is particularly awful, disparaging his wife’s forty-something unmarried friend who’s “missed the bus” (“loose-cogging around the scene, just getting in the way – it’s embarrassing . . . she’s just so pointless”), all the while relishing his mistress’s “autonomy” (naturally, he has fits of jealousy if she mentions any of her male friends). He’s also horrified when his wife turns to her local church for consolation, because he thought he’d successfully “talked her out of” Roman Catholicism (“having itemised the horrid ingredients of that scarlet brew – moral blackmail, misogyny, cannibalism and the rest”). Flora, his wife, is a little too good to be true – running her own business, managing the children (even her friend’s children) with good humour and good sense, and being endlessly supportive of her horrible husband – but it does make the reader care about what happens to her, and I found the novel’s conclusion to be both clever and plausible.

However, I think Madeleine St John’s novels are even better, and I especially recommend A Pure Clear Light, her second novel. Ostensibly, it’s the story of a pair of middle-class Londoners (complete with three beautiful children, a Volvo and summers spent in France) whose marriage starts to unravel when the husband begins an affair, but it’s actually a chance for the author to poke fun at some very shallow, hypocritical people. Simon, the adulterous husband, is particularly awful, disparaging his wife’s forty-something unmarried friend who’s “missed the bus” (“loose-cogging around the scene, just getting in the way – it’s embarrassing . . . she’s just so pointless”), all the while relishing his mistress’s “autonomy” (naturally, he has fits of jealousy if she mentions any of her male friends). He’s also horrified when his wife turns to her local church for consolation, because he thought he’d successfully “talked her out of” Roman Catholicism (“having itemised the horrid ingredients of that scarlet brew – moral blackmail, misogyny, cannibalism and the rest”). Flora, his wife, is a little too good to be true – running her own business, managing the children (even her friend’s children) with good humour and good sense, and being endlessly supportive of her horrible husband – but it does make the reader care about what happens to her, and I found the novel’s conclusion to be both clever and plausible.

I also liked The Essence of the Thing, involving two characters who play minor roles in A Pure Clear Light. Again, an apparently solid relationship is revealed to have deep cracks, and this time, it breaks apart. Nicola simply can’t understand how Jonathan could abandon her so callously, but he’s such an inarticulate, repressed character that the reader can’t help thinking she’s much better off without him. In fact, I can’t understand why any of the women in Madeleine St John’s novels put up with their respective men, but their situations do provide lots of opportunity for thoughtful and often hilarious commentary on love, sex, marriage and modern life. This novel’s plot was a little too predictable and the lessons a little too obvious, but it’s still an enjoyable read. I haven’t read Madeleine St John’s final novel, A Stairway to Paradise, but it’s on my To Read list. I’m so glad I came across this writer. Even if some people regard her as “minor”.

_____

Among her friends and advocates were Bruce Beresford and Clive James, who were her contemporaries at the University of Sydney in the early 1960s. ↩

She worked for decades on a biography of Madame Blavatsky, the founder of the Theosophical Society, but destroyed the manuscript after it was rejected by a publisher. ↩

What are the criteria that differentiate a “minor” from a “major” writer? Is a “minor” novel by a “major” writer superior to a “major” novel by a “minor” writer? And is Michelle de Kretser a “minor” or a “major” writer? Enquiring minds want to know. ↩

July 5, 2013

Miscellaneous Memoranda

- Random House has announced it will commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death by commissioning some “cover versions” of his plays, with Jeanette Winterson reinventing The Winter’s Tale, while Anne Tyler tackles The Taming of the Shrew. The publisher’s press release makes it all sound a bit gimmicky (does Shakespeare really need a project like this to bring him “alive for a contemporary readership”?), but I’d happily read an Anne Tyler version of anything, even the phone book, so I’ll await the results with interest.

- Of course, ‘Random House’ doesn’t actually exist any more. This week, it announced its merger with Penguin, to form ‘Penguin Random House’ (sadly, they ignored my suggested names of ‘Random Penguins’, ‘Penguin House’ and ‘Random Penguin’s House’). I know all about this merger because they decided to send me not one, but three letters about it, telling me how highly they value their authors. (I guess this means they’ll be paying me lots of money soon. Oh, good.)

- It has also been brought to my notice that top renowned best-selling author Dan Brown has a new book out. Okay, some critics say his writing is “clumsy, ungrammatical, repetitive and repetitive” and “full of unnecessary tautology”, but they’re just jealous because he sells millions of books and they don’t. Can those critics afford to buy “a specially commissioned landscape by acclaimed painter Vincent van Gogh and a signed first edition by revered scriptwriter William Shakespeare”? No, I didn’t think so! (For the record, I liked The Da Vinci Code. Come on, it was about the Holy Grail! It had ancient conspiracies and secret codes and high-speed chases through Europe! The only thing missing was Nazis. And homing pigeons. Wait, there may have been Nazis, it’s been a while since I read it.)

- If you’re a young writer and you think you’re as talented as Dan Brown (or possibly, more talented), then you might like to enter the Young Writers Prize (entries close 22nd July) or the John Marsden Prize for Young Australian Writers (entries close 19th August).

- I’ve also been perusing the blog of Stroppy Author, who has some useful advice for old writers (for example, Quit Whingeing And Write Something and Don’t Publish Crap). In addition, it was heartening (sort of) to see that even top renowned best-selling YA authors like Libba Bray get “Them Old, I-Can’t-Write-This-Novel Blues“. (Although I have news for Libba Bray – outlining does not help with this problem. I am a meticulous outliner, and I still spend more time stuck than writing. Coincidentally, I’ve just found out about the Snowflake Method, which I kind of worked out for myself during the process of writing my first couple of novels. If only I’d done a creative writing course and learned about all this stuff! I might have saved myself a lot of time, and maybe even become a top renowned best-selling author.)

- That’s enough about writing for the moment. Here, have a picture of a giant squid:

Giant squid that washed ashore at Trinity Bay, Newfoundland in 1877. Published in ‘Canadian Illustrated News’, October 27, 1877.

June 23, 2013

Looking For A Good, Clean Book

The first time I heard about this, I assumed it was a joke, but apparently this is an actual thing – librarians being asked by adult patrons to recommend ‘clean’ books. ‘Clean’ means different things to different readers, which must make it difficult for the librarians, but generally, these readers are looking for books untainted by ‘language’ (that is, swearing), sex and violence. Sometimes the readers are looking for a suitable book for their children, but often, they are adults looking for a book for themselves that, in the words of one Christian blogger, “won’t be a near occasion of sin”.

Luckily, these readers don’t have to rely on librarians for recommendations, because there are a number of blogs and websites that review and recommend books based on such criteria. The most well-organised and thorough site seems to be Compass Book Ratings (formerly SqueakyCleanReads.com), which I came across because it rated one of my own novels. As Compass Book Ratings rightly points out, movies, TV shows and games are rated, so why not books? This website rates books for children, teenagers and adults, with books given a rating for literary quality (from one to five stars), three separate ratings for profanity/language, violence/gore and sex/nudity (from zero to ten) and a recommended age range (9+, 12+, 14+, 16+, 18+ and 21+). A handy search page means that a reader can search by genre, ratings and recommended age ranges to compile a ‘clean’ reading list, or alternatively, the reader can check the ratings of a particular book.

Luckily, these readers don’t have to rely on librarians for recommendations, because there are a number of blogs and websites that review and recommend books based on such criteria. The most well-organised and thorough site seems to be Compass Book Ratings (formerly SqueakyCleanReads.com), which I came across because it rated one of my own novels. As Compass Book Ratings rightly points out, movies, TV shows and games are rated, so why not books? This website rates books for children, teenagers and adults, with books given a rating for literary quality (from one to five stars), three separate ratings for profanity/language, violence/gore and sex/nudity (from zero to ten) and a recommended age range (9+, 12+, 14+, 16+, 18+ and 21+). A handy search page means that a reader can search by genre, ratings and recommended age ranges to compile a ‘clean’ reading list, or alternatively, the reader can check the ratings of a particular book.

For example, here is the Compass Book Ratings review of The FitzOsbornes in Exile (which is, I think, a fair and generally positive review). The book gets a four-star rating for literary quality and is recommended for readers aged sixteen and above. It receives a rating of two out of ten for profanity (“8 religious exclamations; 7 mild obscenities”), two out of ten for violence (with a list of all the violent incidents in the book, such as “a character is shot, but suffers no permanent injury”) and four out of ten for sex/nudity (again, with a list of incidents). There’s also a listing for “Mature Subject Matter” (“War, Homosexuality, Refugees, Persecution of ethnic groups”) and “Alcohol/Drug Use” (I was puzzled here by the claim that “a 14 year old smokes cigarettes”, until I realised it referred to a brief mention of Javier, the chain-smoking Basque refugee). This all seemed fairly accurate to me, although I must admit I’ve never counted the number of swear words, and I do think a fourteen- or fifteen-year-old could read this novel without incurring any permanent moral or psychological damage. And really, if a reader is going to be disturbed by “7 mild obscenities”, a “discussion about Oscar Wilde’s homosexuality” or a mention of “periods”, then I don’t want them to waste their time or money reading The FitzOsbornes in Exile.1

Of course, ratings for a book aren’t very meaningful unless you can compare them to other familiar books, so I looked up the ratings for The Great Gatsby. Good news for me! It gets four stars, which means my book is of the same literary quality as the Great American Novel! The Great Gatsby is slightly more profane (a rating of three) and violent (a rating of five), but oddly, is reported to contain no sex or nudity at all. Really? The FitzOsbornes in Exile is more confronting than The Great Gatsby, regarding sexual morality?

Then I looked for books with higher (that is, less ‘clean’) ratings and found reviews of Jasper Jones (which gets a ten for profanity, nine for violence and eight for sex, and is described as “well-crafted” but “overwhelming”) and The Fault in Our Stars (which gets a more positive review, but a ten for profanity and a six for sex). What was more confusing to me were the recommended age ranges for books. Jasper Jones is recommended for eighteen years and over, but a book of quotations about Jane Austen (which has no profanity, sex or violence at all) is strictly for readers twenty-one and above. ‘Clean’ books on the topics of family life and motherhood are also recommended only for readers well into adulthood, so I assume the reviewers are making judgements here about reader interests, rather than the books’ potential to cause moral harm. But no, wait. The reviewer of Persepolis says that the “use and amount of profanity in this book would make it inappropriate for anyone under the ages of 21″, while To Say Nothing Of The Dog is twenty-one-plus because it has slow pacing. Okay . . .

Despite the website claiming to have a “formalized content review process” that produces “consistent results”2, the ratings really depend on the individual reviewers, who vary in their qualifications and reviewing philosophies. The reviewers range from a thoughtful high school English teacher with experience on a library board, who wants to find books “that are both enjoyable and relevant to my students and acceptable to their parents as far as content is concerned” and who states “I do not believe in censorship, but I do believe there is an important place for content advisory”, to a student who proudly states she will “throw books across the room on occasion if the content is inappropriate or distasteful” and another young woman who is horrified by “seemingly great books that end up having WAY too much content”. Otherwise, the reviewers are not exactly representative of the general population. All the reviewers are white and, while it doesn’t explicitly state this anywhere on the website, I wondered if the site was affiliated, if only informally, with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, otherwise known as the Mormons3.

Apart from the variable quality of the reviews, I had Issues with Compass Book Ratings. (Yes, I know the site’s not for readers like me, who’ll read just about anything. I’m still allowed to have an opinion on it, especially if it rates my books.) I’m concerned that the site provides lists of ‘objectionable content’ without any context, which can then be used as ammunition by people who want to ban books that they haven’t bothered to read. And I have a problem with keeping teenagers away from ‘objectionable’ content in books, anyway. Surely it’s safer for them to read about these things before they encounter them in real life, so they’ve had a chance to think about them and discuss them? And if there are adult readers who’ll be psychologically damaged by accidentally picking up a book that contains any mention of sex, nudity, violence or swearing, then maybe they should consider abandoning reading altogether and taking up a safer hobby, like knitting. But mostly, I’m disappointed that Compass Book Ratings hasn’t reviewed the Bible. Violence and gore and sex and nudity? Surely they’d have to rate that book ten out of ten.

_____

Honestly, I’d love it if all those readers would avoid my books entirely. Then they’d stop ranting on the internet about how disgusting my books are, and they wouldn’t feel any need to direct their homophobic readers to my own LGBTQ-themed blog posts, and we’d all be much happier. ↩

The website recently added some disclaimers on this page, which makes me wonder if they’ve had some complaints about inconsistent ratings. Those disclaimers weren’t there when I first encountered the site, and the site owners haven’t removed the ‘less consistent’ reviews. ↩

The site seems to be based in Utah, at least one reviewer graduated from Brigham Young University, and the site gives glowing reviews to a number of books written by and about Mormons. ↩