Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 25

June 15, 2013

The Cats of Montmaray (Plus, Les Chats Du Château)

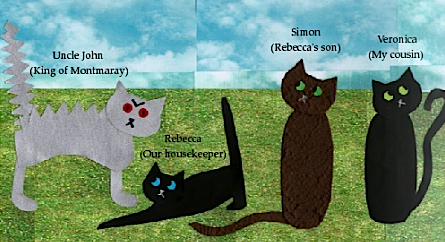

I know this blog has been rather Montmaray-heavy lately, and I will get back to my usual (non-Montmaravian) book ramblings soon, but I just had to share this with you. Ellie Maish, a very talented teenage artist, has created an amazing picture book based on A Brief History of Montmaray as a school project. Ellie has kindly allowed me to post some of the pictures from her book, The Cats of Montmaray, here. And yes, the Montmaravians are all portrayed as cats. Here are a few of the characters:

Don’t you love spiky John-Cat and worshipful Rebecca-Cat? And how Simon-Cat and Veronica-Cat are pointedly looking in opposite directions?

Here’s a scene in the Great Hall featuring the Fabergé egg:

All the castle scenes are beautifully realised in collage form, but I particularly liked the ornate Gold Room. Whatever you do, don’t flop on the bed:

There’s plenty of action and adventure, too. On this page, Sophie-Cat is horrified by the sight of the dead . . . well, he’s not actually a dead Nazi in this book. He’s an evil hawk, with two-inch-long talons and a sharp beak that could easily carry off a defenceless cat. He still ends up dead under a rug, though:

Isn’t it great? Thanks, Ellie.

In other Montmaravian news, a French university student who translated A Brief History of Montmaray as part of her studies has sent me the translation, and I am very impressed. Mind you, I can’t actually read French, but the text looks so much more elegant in French than it does in English. I am having lots of fun reading about “Carlos, notre chien d’eau portugais” and “les pigeons voyageurs” and, of course, “les chats du château”.

June 5, 2013

Montmaravian Miscellanea

Kate Forsyth very kindly invited me to write a guest post for her blog, so I wrote one about books similar to the Montmaray Journals. Even though I’ve mentioned many of those books before, that post is worth visiting for the fabulous book cover images Kate has found, especially that vintage edition of The Pursuit of Love, with its titillating tagline (“Now Linda’s respectable uncles were sure it was true . . . THEIR NIECE WAS A KEPT WOMAN!”).

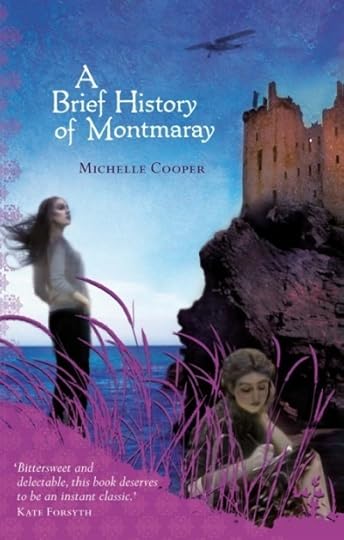

There’s an interview with me coming up later this week on Kate’s blog, and she’s also written a lovely review of the Montmaray books. As Kate explains, she was one of the first people to read the manuscript of A Brief History of Montmaray. This wasn’t because I knew her, but because my editor at Random House had worked with her and thought Kate might enjoy the story. Kate’s comments about the manuscript made me jump up and down with glee (KATE FORSYTH had read my book! And liked it!) and a quote from her subsequently appeared on the front cover of the first edition of the book:

Thank you, Kate.

By the way, that cover for A Brief History of Montmaray is one of my favourite Montmaray covers, partly because of the beautiful shades of blue and the tall purple grass, and partly because it’s the only one that shows all three Montmaravian princesses. (What do you mean, you can’t see Henry? There she is, standing on the castle wall!)

May 27, 2013

That’s How You Say It

Have you ever wondered how to pronounce the names of Paolo Bacigalupi or Jaclyn Moriarty or Maggie Stiefvater? Ever wondered if Elizabeth Wein’s last name is German, or if Jasper Fforde’s accent sounds as posh as his name? Well, wonder no more, because now you can listen to all these authors talk about their names at the .

And yes, I’m there, too. You wouldn’t think anyone could mispronounce a name like ‘Michelle Cooper’, but you’d be surprised at how many of my teachers at school used to read out my name as ‘Michael Copper’. Anyway, I’m glad this resource exists, because if I ever meet Meg Cabot, I’ll now be able to say her name correctly. (All these years, I’ve been pronouncing her last name in my head as CaBOT, when it actually rhymes with ‘habit’).

May 8, 2013

Meet The Mitfords

Last week, I was at the library and noticed a new book about Nancy Mitford, this one about her relationship with French politician and diplomat, Gaston Palewski. I opened the book to a random page and not only recognised the anecdote being related, but knew at once where the quotes had come from. At that moment, I realised I’d read far too many books about the Mitfords and didn’t need to read another one. But then I considered that perhaps readers of this blog might be interested in some of the Mitford-related books I’ve read. Hence this post.

The Mitfords were what Wikipedia1 accurately calls “a minor aristocratic English family”. None of the famous Mitford sisters, with the possible exception of Jessica, ever had any effect whatsoever on political events or world history. They are mostly remembered because they were rich, good-looking, opinionated aristocrats who knew a lot of famous and influential people during a fascinating period of history. More importantly, they were writers, so we have detailed records of their thoughts, observations and jokes. But I ought to introduce the Mitford siblings properly, so here they are:

[image error]1. Nancy (1904 – 1973) was the author of the wonderful comic novels, The Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, as well as several other novels and biographies, and numerous essays and newspaper articles. She was unhappily married to Peter Rodd, but the love of her life was Gaston Palewski and she moved to France to be with him after the Second World War. There are several published collections of her letters, including The Letters of Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh, edited by Charlotte Mosley. Life in A Cold Climate by Laura Thompson is a fairly good biography of Nancy, provided you can cope with the biographer’s prose style (sample sentence: “Yet there is a quality to her voice, as she lingers on their paradisiacal images, that reveals what was always there, and what constitutes so great a part of her appeal: the yearning soul within the sophisticate’s carapace: the imagination that can take illusion and make it into something real.” Oh, how Laura Thompson loves semi-colons! And also, hates feminists. But then, so did Nancy.)

2. Pamela (1907 – 1994) was married to physicist and RAF pilot Derek Jackson, but she divorced him to spend the rest of her life with female ‘companions’. Not that you’ll ever hear a Mitford sister using the word ‘lesbian’ to describe Pamela. Pamela seemed the most sensible and practical of the sisters, and enjoyed breeding poultry and cooking elaborate meals.

3. Thomas (1909 – 1945) was the only boy and the heir to the title, and seems to have been adored by everyone. At school (Eton, naturally), he was the lover of Hamish St Clair-Erskine (to whom Nancy was once, disastrously, engaged) and James Lees-Milne, although Tom seemed to have preferred women in later life. He joined the British army and was killed in Burma during the war, having refused to fight against the Nazis.

4. Diana (1910 – 2003) was the beauty of the family. She married Bryan Guinness at the age of eighteen, but dumped him when she fell in love with Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists. She married Mosley in Berlin in 1936, at a ceremony at which Adolf Hitler was the guest of honour, then she and Mosley were imprisoned without trial in Britain for several years during the war. After the war, she supported Mosley’s various unsuccessful attempts to re-enter politics and they hung out with other rich Fascists. Anne de Courcy’s biography, Diana Mosley, provides a good account of Diana’s life, although it’s a rather biased one (“I came to love Diana Mosley,” gushes the biographer in her introduction, while also describing Diana, despite all the evidence to the contrary, as “the cleverest of the six Mitford sisters”). Diana also wrote a self-serving autobiography, A Life of Contrasts, which is interesting due to the sheer, gobsmacking awfulness of her opinions. Hitler, according to Diana, was a lovely man and the Holocaust wasn’t his fault at all. No, it was due to “World Jewry” and their “virulent attacks upon all things German and their insistent calls for trade boycotts, military encirclement and even war”. Also, the number of Holocaust victims was exaggerated, and anyway, Stalin and Mao killed far more people. She also spends a lot of time boasting about her social life (“At Mona Bismarck’s Paris Christmas dinner parties, I was always put next to the Duke [of Windsor]“) and going on about Mosley’s “brilliance”, and, with an apparent lack of irony, writes of her enemies, “This is typical of many people who reject truth in even the most trivial matters if it conflicts with a prejudice”).

4. Diana (1910 – 2003) was the beauty of the family. She married Bryan Guinness at the age of eighteen, but dumped him when she fell in love with Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists. She married Mosley in Berlin in 1936, at a ceremony at which Adolf Hitler was the guest of honour, then she and Mosley were imprisoned without trial in Britain for several years during the war. After the war, she supported Mosley’s various unsuccessful attempts to re-enter politics and they hung out with other rich Fascists. Anne de Courcy’s biography, Diana Mosley, provides a good account of Diana’s life, although it’s a rather biased one (“I came to love Diana Mosley,” gushes the biographer in her introduction, while also describing Diana, despite all the evidence to the contrary, as “the cleverest of the six Mitford sisters”). Diana also wrote a self-serving autobiography, A Life of Contrasts, which is interesting due to the sheer, gobsmacking awfulness of her opinions. Hitler, according to Diana, was a lovely man and the Holocaust wasn’t his fault at all. No, it was due to “World Jewry” and their “virulent attacks upon all things German and their insistent calls for trade boycotts, military encirclement and even war”. Also, the number of Holocaust victims was exaggerated, and anyway, Stalin and Mao killed far more people. She also spends a lot of time boasting about her social life (“At Mona Bismarck’s Paris Christmas dinner parties, I was always put next to the Duke [of Windsor]“) and going on about Mosley’s “brilliance”, and, with an apparent lack of irony, writes of her enemies, “This is typical of many people who reject truth in even the most trivial matters if it conflicts with a prejudice”).

5. Unity (1914 – 1948) was the one who was obsessed with Hitler and shot herself in the head when war broke out. A lot of her attention-seeking behaviour seems to have been due to a childish desire to shock people, but she was in her twenties when she met Hitler, surely old enough to know better. Was she emotionally or intellectually immature, or simply caught up in the political excitement of the 1930s? Her biography, Unity Mitford: A Quest, by David Pryce-Jones, doesn’t really help to answer this question. The biographer has clearly done a lot of research, interviewing more than two hundred of her acquaintances, but the result is a very dull and disorganised account of her life, with little attempt at analysis. I really can’t recommend this book (unless, of course, you happen to be writing a novel that includes Unity as a character).

6. Jessica (1917 – 1996) ran away as a teenager to the Spanish Civil War with Esmond Romilly, Winston Churchill’s Communist nephew. A lot of very sad things happened in her personal life – her baby daughter died of measles, Esmond was killed in action during the war, her elder son died at the age of ten – but these are all glossed over in her memoir, Hons and Rebels, because Mitfords were brought up to put on a brave face in public. Jessica married Robert Treuhaft in 1943, and the two of them were active members of the American Communist Party and passionate civil rights campaigners. Jessica also wrote a number of books based on her investigative journalism, including exposés of the American funeral industry and prison system. Bonus fact: J. K. Rowling so admired Jessica Mitford that she named her daughter after Jessica.

7. Deborah (1920 – ) married Andrew Cavendish, who became the Duke of Devonshire, and then she turned Chatsworth, the Devonshire family home, into a thriving business and tourist attraction. She also had terrible things happen in her life – three of her children died at birth, and her husband turned out to be a philandering alcoholic – but as Charlotte Mosley observed, Deborah was a Mitford, and therefore used to hiding her “vulnerability behind a lightly worn armour of flippancy and self-deprecation”. Deborah is usually portrayed as the apolitical Mitford, but is a proud Tory, was close to Diana, and “adored” Mosley. She has written several books about Chatsworth and her life, the most recent of which is Wait For Me! Memoirs of the Youngest Mitford Sister.

There have also been a number of books about the whole Mitford family. I think the best, most balanced, family history is The Mitford Girls by Mary S. Lovell, although it’s been a while since I read it. There’s also The House of Mitford, by Jonathan Guinness with Catherine Guinness, or, as Hermione Granger would call it, A Highly Biased and Selective History of the Mitfords. The authors are Diana’s son and grand-daughter, so Diana is portrayed as a saint and Jessica as the devil incarnate. It also starts with a very long and boring section about the Mitford sisters’ ancestors. Still, it includes a lot of fascinating family photos that you won’t find in other books. However, my favourite Mitford-related book would have to be The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters, edited by Charlotte Mosley. Yes, she’s Diana’s daughter-in-law and she seems to have done some very selective editing when it comes to Diana’s letters from the 1930s, but she has also done an excellent job of writing introductions and explanatory footnotes (which is vital, when the letter writers use as many nicknames as the Mitfords do) and of arranging all the correspondence in a way that makes sense. To quote J.K. Rowling again, “The story of the extraordinary Mitford sisters has never been told as well as they tell it themselves”.

There have also been a number of books about the whole Mitford family. I think the best, most balanced, family history is The Mitford Girls by Mary S. Lovell, although it’s been a while since I read it. There’s also The House of Mitford, by Jonathan Guinness with Catherine Guinness, or, as Hermione Granger would call it, A Highly Biased and Selective History of the Mitfords. The authors are Diana’s son and grand-daughter, so Diana is portrayed as a saint and Jessica as the devil incarnate. It also starts with a very long and boring section about the Mitford sisters’ ancestors. Still, it includes a lot of fascinating family photos that you won’t find in other books. However, my favourite Mitford-related book would have to be The Mitfords: Letters Between Six Sisters, edited by Charlotte Mosley. Yes, she’s Diana’s daughter-in-law and she seems to have done some very selective editing when it comes to Diana’s letters from the 1930s, but she has also done an excellent job of writing introductions and explanatory footnotes (which is vital, when the letter writers use as many nicknames as the Mitfords do) and of arranging all the correspondence in a way that makes sense. To quote J.K. Rowling again, “The story of the extraordinary Mitford sisters has never been told as well as they tell it themselves”.

_____

Wikipedia once noted in its ‘Mitfords in Popular Culture’ section that “Unity Mitford appears as a minor character in the last two books of Michelle Cooper’s Montmaray Journals trilogy”, but this sentence has now disappeared. Wikipedia also fails to mention the most famous popular culture reference to the Mitford sisters – that is, Narcissa, Bellatrix and Andromeda Black in the Harry Potter books, who bear a strong resemblance to Diana, Unity and Jessica Mitford. ↩

April 28, 2013

More Of What I’ve Been Reading Recently

Last month, Bookshelves of Doom hosted a celebration of Elizabeth Peters, an American author I’d never read, so I decided to check out some of her novels. I started with The Seventh Sinner, the first in a series about Jacqueline Kirby, librarian and amateur sleuth. The story involved international graduate students living in Rome and featured many of the standard elements of a murder mystery – a victim who scrawls a cryptic message in the dust before expiring, a small group of suspects who all hated the victim and who persist in doing mysterious, suspicious things, a debonair detective (who may or may not be working in conjunction with the amateur sleuth), and a dramatic revelation and confession in the penultimate chapter (at a costume party, of course). The book was also written in the 1970s, so the women all stoically endure being groped and ogled, the one young woman who’s as sexually active as the men is constantly derided for being a slut, and there are a lot of unfunny jokes about Women’s Lib. On the other hand, the descriptions of the Roman archaeological sites were absolutely fascinating, and Jacqueline was snarky and interesting enough for me to consider reading another (more recent) book in this series.

I also read The Hippopotamus Pool, by the same author, starring Amelia Peabody, a parasol-wielding Egyptologist with a talent for solving mysteries. This was a bit like a Victorian-era Indiana Jones, but much smarter and with better jokes. There were noble archaeologists, vicious criminal masterminds, mysterious orphans, secret cults, long-lost tombs, disappearing mummies, kidnappings, murders and a bit of romance, all packed into a fast-paced, exciting story. Amelia was a clever and amusing narrator, but my favourite character would have to be Ramses, her twelve-year-old son, who never shuts up and also happens to be an expert in ancient languages and a master of disguise. (His cat, Bastet, was pretty great, too.) The only character I couldn’t stand was Emerson, Amelia’s husband, who kept losing his temper, ripping off his shirt and cursing at the ‘natives’. Is he supposed to be some sort of endearing parody of machismo? I kept hoping he’d get a horrible contagious disease and be quarantined in Cairo, so that Amelia and Ramses could get on with solving the mystery by themselves. I also assumed Amelia and her family and friends were American, based on their language and behaviour, but no, I think they’re meant to be English. I’m guessing the author’s research into Victorian England was limited to learning about ladies’ fashions. However, her knowledge of ancient Egypt is very impressive and she weaves facts (and real historical figures, such as Howard Carter) into her story beautifully. I’d definitely like to read more of this series, especially if I can find a book where Emerson goes missing for most of the story.

I also enjoyed Wonder, by R. J. Palacio – although ‘enjoyed’ is possibly the wrong word, given how much I cried while reading this novel. It’s the tale of ten-year-old August, who has craniofacial deformities and a hearing impairment, and has been home-schooled while enduring years of surgery and therapy. However, his mother decides he’s now ready to join the wider world, so he starts fifth grade at the local private school. There are multiple narrators – August, his protective older sister Olivia, her boyfriend Justin, her former best friend Miranda, and various students at August’s school – which is a clever way of revealing the complex motives behind people’s actions. All of the characters are engaging and, more importantly, they’re real. August, for example, is smart, brave and stoic, but he can also be selfish and manipulative. Olivia loves her little brother, but she can’t help resenting that August gets all her parents’ attention. August may believe that none of his school friends have any problems in their lives, but he gradually learns that that’s not true. I especially liked the portrayal of August’s parents, and his sensible, kind school principal. The final chapters of the book descend into pure schmaltz (I was half-expecting Oprah to turn up on stage at the school assembly and initiate group hugs), but August was so endearing that I was happy to see him triumph over the bullies and bigots.

Finally, I was entertained and educated by The Curse: Confronting the Last Unmentionable Taboo, Menstruation, by Karen Houppert, which was a well-written account of cultural attitudes to menstruation in the United States. The author examines some hilarious historical advertisements, pamphlets and sex-education films, including a “menstrual classic” called Molly Grows Up, shown in American classrooms in the 1950s (in one scene, Molly’s teacher urges restraint during Those Days, saying “You can dance, but don’t do any strenuous dancing like square dancing”). Ms Houppert also notes that Catholic priests campaigned against tampons in the 1930s (apparently, they “worried that women would find them erotic. And they worried that girls would lose their virginity upon insertion”). And did you know that Disney refuses to allow any ads for menstrual-related products during its television programs? And that modern sanitary pads and tampons almost never have the words ‘period’, ‘blood’ or ‘menstruation’ written on their packets? (Naturally, I had to conduct my own bathroom-cabinet survey to investigate this. It’s true! Only one packet of pads mentioned the word ‘period’, but it was in tiny writing and only appeared once, and there was no mention of ‘blood’. Apparently, pads and tampons only exist to provide ‘protection’ against ‘flow’, ‘fluid’ and ‘moisture’. Isn’t that weird?) The book also describes how men in the late nineteenth century used menstruation as a reason to exclude women from higher education and the medical profession (after all, a woman has a “body and mind which for one quarter of each month, during the best years of life, is more or less sick and unfit for work”) and how taboos about menstruation allowed the manufacturers of tampons and dodgy PMS ‘cures’ to get away with unethical behaviour that put women’s lives at risk. I can’t say I was convinced by all of the author’s arguments, but she had clearly done a lot of research on the subject, including some fascinating interviews with pre-adolescent girls at summer camp about their perceptions of menstruation. “We’re talking about periods,” one girl shouts. “It’s very bloody!”

April 13, 2013

It’s That Time of Year Again . . .

That is, the time of year when literary award shortlists are announced. Congratulations to all the writers whose work was recently recognised in the Children’s Book Council of Australia awards, the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards and the inaugural Stella Prize.

It’s also a time of literary festivals, including the Sydney Writers’ Festival. Young Adult literature events on the program include a panel discussing YA fantasy (Kate Forsyth, S.D. Gentill and K.B. Hoyle with Judith Ridge) and another featuring Libba Bray and Justine Larbalestier in conversation with literary agent Barry Goldblatt. For those who were Young Adults in the 1980s, Molly Ringwald will be there, too, talking about her new book. Yes, apparently she writes books these days, when she’s not busy being a “silk-voiced jazz chanteuse”. There are also several writing masterclasses for young writers, led by Jacqueline Harvey, Oliver Phommavanh and Sue Whiting, and lots of workshops for grown-up writers.

Of even greater interest to YA readers and writers is Reading Matters, in Melbourne. This year’s program includes Libba Bray, Gayle Forman, Garth Nix and Alison Croggon, and promises lots of interesting discussions.

April 6, 2013

Five Ways In Which Writing A Novel Is Like Making A Quilt

1. When you first start making quilts (or writing novels), it’s probably best to keep the structure simple and use only a couple of colours. That way, you won’t get overwhelmed, and it won’t take you years and years to finish. Simple things can still be interesting.

2. Even if you follow a pattern, you’ll use your own materials and probably change the size, so you’ll end up with something that only you could have produced. (This can be a good or bad thing, depending on your skills.)

3. When you’re piecing a quilt together, you need to consider how the elements will look when placed next to each other. It’s more interesting if there are various shades of light and dark beside each other.

For some reason, everything I produce is tinged with blue.

4. You will start off with a lot of enthusiasm and energy, but halfway through, you will wonder why you ever began this project. You will make lots of mistakes. Things may begin to unravel.

But problems can always be fixed with a bit of effort and skill.

They can even be fixed years later. If, for example, you sit your malfunctioning printer on your bed and it leaks ink over your quilt. Ha ha ha, as if anyone would be so silly as to do that!

5. In the end, you will be glad you persisted, because you will have created something that is warm and beautiful and comforting. Wait, that only applies to quilt-making. Probably. Depends what sort of novels you write.

March 24, 2013

Same-Sex-Attracted Gentlemen in English Society in the 1930s and 1940s

I’ve been meaning to write a blog post on this topic ever since The FitzOsbornes in Exile was first published in North America (that is, two years ago, which says something about my blogging habits). I don’t want to give away any plot spoilers to those who haven’t read the book, but let’s just say that it’s set in the late 1930s, in England, and that at least one male character is gay1. A surprising number of readers seemed to assume that any well-brought-up young lady of this time and place would have been shocked, horrified and outraged at the very idea of homosexuality, and that all gay men were shunned by Society and were in constant danger of being carted off to prison, à la Oscar Wilde. So, there were a number of comments from readers about how ‘implausible’ it was that Sophie and Veronica, the two young ladies at the centre of the story, would be so accepting of their gay male relative.

Now, it’s true that any kind of sexual activity between men was illegal in England between 1885 and 19672, but it’s also true that these laws were applied very selectively. In general, rich, aristocratic men were free to do whatever they liked. Yes, Oscar Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency”, but that was an unusual case because he started the whole thing off (by bringing a libel action against his boyfriend’s belligerent father, when what the father was saying about Wilde was mostly true). Anyway, that case was in 1895, forty-two years before the events of The FitzOsbornes in Exile. Consider current attitudes to gay issues, and compare this to how most people thought in the early 1970s, and you’ll see that things can change significantly in forty-two years. The fact is that in the 1930s and 1940s, there were quite a lot of popular, important and influential same-sex-attracted men who were part of English Society. Here are some of them.

First, the obvious ones. In the world of theatre and music, the most famous were probably Ivor Novello, Noël Coward and Benjamin Britten. There was also stage designer Oliver Messel, who was closely associated with the British royals and designed Princess Margaret’s Caribbean house. Norman Hartnell and Hardy Amies held Royal Warrants to design frocks for various British royals (Hardy Amies also happened to be a Special Operations Executive agent who worked with the Belgian resistance during the war), while the crème de la crème of Society queued up to be photographed by Cecil Beaton.

Ivor Novello

Meanwhile, the Bloomsbury set was not, strictly speaking, part of respectable Society, but it was influential and included writer Lytton Strachey, economist John Maynard Keynes and artist Duncan Grant.

Those with connections to Oxford included Maurice Bowra (Warden of Wadham College, later Vice-Chancellor of the university and awarded a knighthood), Brian Howard (poet, journalist, supposedly an inspiration for the character of Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited) and Harold Acton (writer, also supposedly a model for Anthony Blanche). Other famous same-sex-attracted male writers were Siegfried Sassoon, Raymond Mortimer and E.M. Forster.

Then there were a whole lot of aristocrats who didn’t do much, but were certainly accepted in Society, starting with Prince George (brother of King Edward VIII and King George VI), whose male lovers were rumoured to have included his cousin Louis Ferdinand, Prince of Prussia, Noël Coward and Anthony Blunt (art historian, cousin to the Queen, Communist spy). There was also Stephen Tennant, who “spent most of his life in bed” and supposedly inspired the character of Cedric in Love In A Cold Climate. However, I think my favourite aristocrat would have to be Gavin Henderson, 2nd Baron Faringdon: “Described by David Cargill as a ‘roaring pansy’, Henderson was known for his effeminate demeanour, once opening a speech in the House of Lords with the words ‘My dears’ instead of ‘My Lords.’”

What is more interesting to me is the number of gay men in positions of real political power, either in the House of Commons or the diplomatic services. For example, Oliver Baldwin, son of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, had a long career in politics, first as a Labour MP, then as Parliamentary Secretary to the Secretary for War. When he was appointed Governor of the Leeward Islands, a British colony in the Caribbean, he took his partner, John Boyle, with him. Other politicians included Henry ‘Chips’ Channon, Harold Nicolson, Tom Driberg and Robert Boothby. It’s true that these men did not always receive unconditional positive regard from their family and colleagues. For example, Oliver Baldwin never became a government minister, despite his experience and political connections. He was also recalled from the position of Governor after three years (although this was more because he supported socialism and anti-colonial attitudes in the islands than because the white colonials were scandalised by his relationship with John Boyle – and Oliver’s parents did eventually come to accept his partner as almost a son-in-law).

Some of these men had long, happy, unconventional marriages with women (for example, Harold Nicolson’s marriage to Vita Sackville-West); some entered into brief or unhappy marriages in an attempt to placate their families and produce an heir; others were ‘confirmed bachelors’. Some of them were definitely gay, others were probably bisexual, and very few of them were ‘out’ in the public sense that we mean now. But all of these men participated in Society, and other people in Society knew about them and accepted them to varying degrees – which isn’t so different from the way things are now.

So I think Sophie and Veronica’s attitudes in The FitzOsbornes in Exile are entirely plausible – especially as neither of them is particularly religious, and Veronica makes a habit of rebelling against conservative values. And I also think Veronica would have loved a chance to debate Marxism with Oliver Baldwin.

_____

Yes, I know they probably wouldn’t have used the word ‘gay’ in 1937, but the vast array of words used for male homosexuality in the twentieth century would take up an entire blog post of their own. For those who are interested, A Dictionary of Euphemisms, by Judith S. Neaman and Carole G. Silver, has a good discussion of North American, British and Australian terms. ↩

Lesbians did not exist, according to the law. ↩

March 11, 2013

What I’ve Been Reading Recently

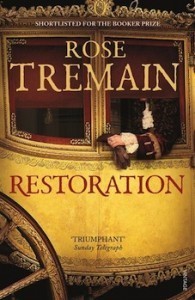

I absolutely loved Restoration by Rose Tremain, about a medical student in Restoration-era England who attracts the patronage of King Charles II after (accidentally) saving the life of the King’s spaniel. Robert Merivel is a most endearing character, despite his many faults, which include laziness, gluttony and a complete inability to resist temptation. He has a good heart and a robust sense of humour, and he humbly accepts his punishment when he does the unforgivable and falls in love with the King’s mistress. All the other characters are equally vivid and interesting, but my favourite is Merivel’s best friend, Pearce, who works at a remote Quaker-run lunatic asylum. The author does a wonderful job of recreating the era in a manner that is accessible without feeling too ‘modern’. It’s true that Merivel’s beliefs about medicine are sometimes extremely progressive for his time (for example, he questions bloodletting as a cure and refers to the spread of the “plague germ”), but then, he is meant to be a rationalist in a rapidly changing world. I actually read this book because the sequel, Merivel, was recently published and sounded very interesting, but Restoration is so perfect and complete in itself (ending in exactly the right place) that I wonder why it needed a sequel. However, I can certainly understand why the author would want to spend more time with Robert Merivel, so I’ll probably read Merivel, too – just not right now.

I absolutely loved Restoration by Rose Tremain, about a medical student in Restoration-era England who attracts the patronage of King Charles II after (accidentally) saving the life of the King’s spaniel. Robert Merivel is a most endearing character, despite his many faults, which include laziness, gluttony and a complete inability to resist temptation. He has a good heart and a robust sense of humour, and he humbly accepts his punishment when he does the unforgivable and falls in love with the King’s mistress. All the other characters are equally vivid and interesting, but my favourite is Merivel’s best friend, Pearce, who works at a remote Quaker-run lunatic asylum. The author does a wonderful job of recreating the era in a manner that is accessible without feeling too ‘modern’. It’s true that Merivel’s beliefs about medicine are sometimes extremely progressive for his time (for example, he questions bloodletting as a cure and refers to the spread of the “plague germ”), but then, he is meant to be a rationalist in a rapidly changing world. I actually read this book because the sequel, Merivel, was recently published and sounded very interesting, but Restoration is so perfect and complete in itself (ending in exactly the right place) that I wonder why it needed a sequel. However, I can certainly understand why the author would want to spend more time with Robert Merivel, so I’ll probably read Merivel, too – just not right now.

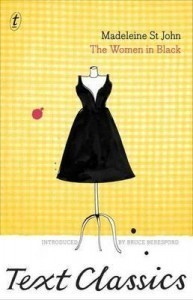

I also enjoyed The Women in Black by Madeleine St John, a charming story about a group of women working at a grand Sydney department store in the 1950s. I loved the descriptions of familiar Sydney experiences: eating lunch by the Archibald Fountain in Hyde Park; catching the train from Wynyard Station; strolling through Martin Place and giving in to the temptation “to walk along the GPO colonnade”. (The only unfamiliar bits were the trams and eating ice-creams at Cahill’s, both before my time.) The author, an Australian who moved to England in 1968 and never moved back, was clearly glad to escape a narrow-minded society that provided her with very limited options. Marriage was then the only acceptable goal for women, although Australian men aren’t exactly portrayed as prizes in this book. For example, Patty’s husband is described as a “drongo . . . neither cruel nor violent, merely insensitive and inarticulate”, while Fay’s two previous lovers have dumped her without marrying her. Meanwhile, young Lisa longs to accept the university scholarship she’s been offered, but her father refuses to sign the permission form (“I can’t see what you want with exams and first-class honours and universities and all that when you’re a girl”). Luckily, Lisa and Fay are taken under the wing of Magda, the ‘Continental’ refugee who happens to have a lot of suave, cultured male friends, and even Patty manages to put aside her bitterness and reach for happiness. The plot of this book is utterly predictable, but that doesn’t matter – read this for the gorgeous, detailed descriptions, the spot-on dialogue and the sympathetic portrayal of female friendship.

I also enjoyed The Women in Black by Madeleine St John, a charming story about a group of women working at a grand Sydney department store in the 1950s. I loved the descriptions of familiar Sydney experiences: eating lunch by the Archibald Fountain in Hyde Park; catching the train from Wynyard Station; strolling through Martin Place and giving in to the temptation “to walk along the GPO colonnade”. (The only unfamiliar bits were the trams and eating ice-creams at Cahill’s, both before my time.) The author, an Australian who moved to England in 1968 and never moved back, was clearly glad to escape a narrow-minded society that provided her with very limited options. Marriage was then the only acceptable goal for women, although Australian men aren’t exactly portrayed as prizes in this book. For example, Patty’s husband is described as a “drongo . . . neither cruel nor violent, merely insensitive and inarticulate”, while Fay’s two previous lovers have dumped her without marrying her. Meanwhile, young Lisa longs to accept the university scholarship she’s been offered, but her father refuses to sign the permission form (“I can’t see what you want with exams and first-class honours and universities and all that when you’re a girl”). Luckily, Lisa and Fay are taken under the wing of Magda, the ‘Continental’ refugee who happens to have a lot of suave, cultured male friends, and even Patty manages to put aside her bitterness and reach for happiness. The plot of this book is utterly predictable, but that doesn’t matter – read this for the gorgeous, detailed descriptions, the spot-on dialogue and the sympathetic portrayal of female friendship.

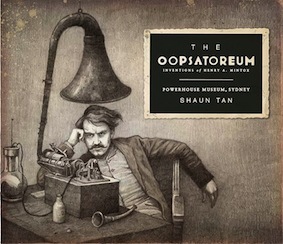

Finally, I’ve been chortling my way through The Oopsatoreum, by Shaun Tan with the Powerhouse Museum. This is an entertaining look at the life of Henry Archibald Mintox (1880–1967), one of Australia’s “most fearless inventors”, whose “sheer diversity of his legacy is matched only by its great lack of practical relevance”. Mr Mintox produced “a startling range of prototype inventions from his back shed in Burrumbuttock, New South Wales, and came to be known as the ‘Edison of Australia’, although only within his own family and at his own insistence.” Among his useless inventions were a ‘lesson trap’ (a giant cage baited with a cupcake for luring in schoolchildren; after being trapped, they’d received “a stern lecture on the perils of tooth decay”); an automated ‘dog walker’ that reeled in the dog after thirty minutes; and a ‘handshake gauge’ for testing the trustworthiness of job applicants. The book consists of photographs of the inventions with short explanations of their history, along with some illustrations in the form of Mr Mintox’s ‘plans’. Mr Mintox is, of course, a figment of Shaun Tan’s imagination, but the ‘inventions’ are actual objects from the Powerhouse Museum (the ‘handshake gauge’, for instance, is “an artificial hand for use with a resuscitation mannequin in first-aid training”). This is a very funny book, let down only by some design flaws (for example, the designer has chosen to place a lot of the illustrations over two adjacent pages, causing details to become invisible where the pages meet the book’s spine; also, the publishers forgot to employ a proofreader). But I’m sure less persnickety readers will overlook this, and it’s certainly a book that Shaun Tan’s many fans will enjoy – and, according to his website, there’s an accompanying exhibition planned for 2013 at the Powerhouse Museum.

Finally, I’ve been chortling my way through The Oopsatoreum, by Shaun Tan with the Powerhouse Museum. This is an entertaining look at the life of Henry Archibald Mintox (1880–1967), one of Australia’s “most fearless inventors”, whose “sheer diversity of his legacy is matched only by its great lack of practical relevance”. Mr Mintox produced “a startling range of prototype inventions from his back shed in Burrumbuttock, New South Wales, and came to be known as the ‘Edison of Australia’, although only within his own family and at his own insistence.” Among his useless inventions were a ‘lesson trap’ (a giant cage baited with a cupcake for luring in schoolchildren; after being trapped, they’d received “a stern lecture on the perils of tooth decay”); an automated ‘dog walker’ that reeled in the dog after thirty minutes; and a ‘handshake gauge’ for testing the trustworthiness of job applicants. The book consists of photographs of the inventions with short explanations of their history, along with some illustrations in the form of Mr Mintox’s ‘plans’. Mr Mintox is, of course, a figment of Shaun Tan’s imagination, but the ‘inventions’ are actual objects from the Powerhouse Museum (the ‘handshake gauge’, for instance, is “an artificial hand for use with a resuscitation mannequin in first-aid training”). This is a very funny book, let down only by some design flaws (for example, the designer has chosen to place a lot of the illustrations over two adjacent pages, causing details to become invisible where the pages meet the book’s spine; also, the publishers forgot to employ a proofreader). But I’m sure less persnickety readers will overlook this, and it’s certainly a book that Shaun Tan’s many fans will enjoy – and, according to his website, there’s an accompanying exhibition planned for 2013 at the Powerhouse Museum.

March 2, 2013

Miscellaneous Memoranda

Otherwise known as, A List Of Things I Bookmarked Months Ago But Didn’t Ever Get Around To Posting On My Blog.

– In January, the American Library Association announced the 2013 Rainbow List of LGBTQ1 books for children & teenagers. At the end of last year, YALSA also blogged about LGBTQ books appearing on lists of the year’s best Young Adult literature and mentioned “several books with secondary or tertiary characters who are LGBTQ and aren’t necessarily struggling with their sexuality . . . It’s wonderful to have books about teens dealing with issues of sexuality and gender, but to me, it says more about the status of LGBTQ characters in YA fiction that there are so many books where the sexuality of gay, bisexual, transgendered, or otherwise queer characters isn’t an issue.” Hear, hear!2

– Remember the kerfuffle a couple of years ago when the Booker Prize judges decided to shortlist books based on ‘readability’ rather than ‘literary quality’? Even though I don’t agree with all of Jeanette Winterson’s criteria for determining whether a novel is Literature, I laughed out loud at this: “The most unreadable books I have read recently were Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series.”

– I was also interested in this article by Lionel Shriver about how women authors behave when shortlisted for literary awards, compared to men: “Any victory that translates into beating someone else makes women feel guilty.” Ms Shriver is impatient with such ‘girly’ attitudes. When asked whether she was surprised that her novel We Need To Talk About Kevin had won the Orange Prize, this was her response:

“No,” I said. And then I made a wrong answer worse by adding, “It’s a good book.”

I wonder if her overt self-confidence, and the reactions of others to this, have more to do with her being a self-confident American living in self-deprecating Britain than her being an ‘ungirly’ woman novelist. I’m also surprised that she believes that literary awards inevitably go to a ‘good book’.3

– There’s been a lot of discussion about New Adult books lately, although I’m still trying to figure out what constitutes Young Adult.

– Courtesy of The Hairpin via Bookshelves of Doom, here are some text messages written by the characters of Little Women. For example, Jo and Meg:

Jo, Father still isn’t dead

really?

I saw him not four hours ago

could have sworn he died at sea

See also, Texts from Jane Eyre:

DID YOU LEAVE BECAUSE OF MY ATTIC WIFE

IS THAT WHAT THIS IS ABOUT

yes

absolutely

BECAUSE MY HOUSE IN FRANCE DOESN’T EVEN HAVE AN ATTIC

IF THAT’S WHAT YOU WERE WORRIED ABOUT

– Australian bloggers may be interested in the 2013 Best Australian Blogs Competition, while writers for children and teenagers might like to check out the Aspiring Writers Mentorship Program (which I’ve previously written about here, for New South Wales writers only) and the Text Prize (for Australian and New Zealand writers only).

– Finally, because you can never have too much Kate Beaton, here’s her take on various Nancy Drew book covers.4

_____

That’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning, in case anyone was wondering. ↩

Especially as one of those “several books” was The FitzOsbornes at War. ↩

Whether We Need To Talk About Kevin is actually a ‘good book’ is another issue, and probably not an issue that Lionel Shriver and I would agree on. ↩

If I had to choose a favourite, it would probably be Mystery of Crocodile Island (“This was not a mystery that needed to be solved.”) ↩