Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 23

January 9, 2014

My Holiday Reading

I wasn’t supposed to be doing any holiday reading – I was meant to be finishing writing a book – but there’s just something about the week between Christmas Day and New Year’s Day in Australia that forces you to lie about in a hammock, eating grapes and reading novels (and by ‘you’, I mean ‘me’). They were pretty good novels, though, and I guess I could argue that, as a writer, reading novels is an essential part of developing my professional skills. See, I wasn’t lazing about, I was working. Anyway, here’s what I read:

All Change by Elizabeth Jane Howard was the fifth and final volume of the Cazalet Chronicles, a family saga set around the time of the Second World War. Although I’ve enjoyed this series very much, the fourth volume was the least compelling and I wasn’t sure a fifth novel was really necessary. It seemed to me as though the Cazalets had finally sorted out their lives for good – but no, in this book, everything falls apart, just as it did for a lot of wealthy English families in that post-war decade of upheaval. In All Change, bankruptcy looms for the Cazalets, although I must admit it was hard for me to feel much sympathy for them. The brothers have inherited a thriving timber business and numerous valuable properties from their father, but are too stubborn to accept business advice from their social inferiors (Hugh), too extravagant (Edward) or too indecisive (Rupert) to manage it effectively. Meanwhile, the women succumb to depression, dementia and terminal illnesses, have unhappy affairs and are exhausted by the demands of their badly-behaved children. There’s a whole new generation of characters that had me constantly referring to the family tree in the front of the book and there were quite a few continuity errors (for instance, Simon is described as having a dead twin, when that’s actually Will, who is mostly absent from this book). But I didn’t care! I devoured all six hundred pages in two days, thoroughly engrossed in the Cazalets’ story and sad that this was truly the end, as Elizabeth Jane Howard died last week at the age of ninety. She left behind a number of excellent novels and a lot of devoted fans of her work.

All Change by Elizabeth Jane Howard was the fifth and final volume of the Cazalet Chronicles, a family saga set around the time of the Second World War. Although I’ve enjoyed this series very much, the fourth volume was the least compelling and I wasn’t sure a fifth novel was really necessary. It seemed to me as though the Cazalets had finally sorted out their lives for good – but no, in this book, everything falls apart, just as it did for a lot of wealthy English families in that post-war decade of upheaval. In All Change, bankruptcy looms for the Cazalets, although I must admit it was hard for me to feel much sympathy for them. The brothers have inherited a thriving timber business and numerous valuable properties from their father, but are too stubborn to accept business advice from their social inferiors (Hugh), too extravagant (Edward) or too indecisive (Rupert) to manage it effectively. Meanwhile, the women succumb to depression, dementia and terminal illnesses, have unhappy affairs and are exhausted by the demands of their badly-behaved children. There’s a whole new generation of characters that had me constantly referring to the family tree in the front of the book and there were quite a few continuity errors (for instance, Simon is described as having a dead twin, when that’s actually Will, who is mostly absent from this book). But I didn’t care! I devoured all six hundred pages in two days, thoroughly engrossed in the Cazalets’ story and sad that this was truly the end, as Elizabeth Jane Howard died last week at the age of ninety. She left behind a number of excellent novels and a lot of devoted fans of her work.

I also read Journey to the River Sea by Eva Ibbotson, an excellent children’s novel about an orphaned girl sent to live in Brazil in 1910. Among the characters Maia encounters are a stalwart governess with a mysterious past, a travelling troupe of actors, a kindly scientist, a missing heir to an English estate, a Russian count and a couple of evil (but fortunately, incompetent) private investigators. As always with Eva Ibbotson’s books, the heroine is a little too good to be true (beautiful, intelligent, a talented musician, a skilled dancer, friendly and kind to all people and animals, etc), but the story and setting were fascinating and I enjoyed following Maia’s adventures.

However, my favourite holiday read would have to be A Long Way From Verona by Jane Gardam, a brilliant coming-of-age novel set during the Second World War. Jessica is a bright, imaginative, melodramatic twelve-year-old who is utterly tactless and incapable of dissembling, yet convinced that she alone is able to understand others perfectly (meanwhile, wondering why she isn’t more popular at school). She gets into trouble constantly – for handing in a forty-seven-page essay that is not actually about ‘The Best Day of the Summer Holidays’, for eating potato chips on the train in an unladylike fashion, for hiding out in the library and reading ‘unsuitable’ books such as Jude the Obscure – and her idiosyncratic observations of her world are clever and hilarious. Here, for example, is her description of a stranger’s front parlour, in which she and her friends find themselves after a prank goes wrong:

However, my favourite holiday read would have to be A Long Way From Verona by Jane Gardam, a brilliant coming-of-age novel set during the Second World War. Jessica is a bright, imaginative, melodramatic twelve-year-old who is utterly tactless and incapable of dissembling, yet convinced that she alone is able to understand others perfectly (meanwhile, wondering why she isn’t more popular at school). She gets into trouble constantly – for handing in a forty-seven-page essay that is not actually about ‘The Best Day of the Summer Holidays’, for eating potato chips on the train in an unladylike fashion, for hiding out in the library and reading ‘unsuitable’ books such as Jude the Obscure – and her idiosyncratic observations of her world are clever and hilarious. Here, for example, is her description of a stranger’s front parlour, in which she and her friends find themselves after a prank goes wrong:

“We tiptoed over it into a fearfully clean front room with the coals arranged on the sticks like a jigsaw, and the arm-chairs made out of brown skin and never sat on, and a terrified-looking plant standing eyes right in the window, wishing it were dead.”

Jessica is told by a visiting author that she is A WRITER BEYOND ALL POSSIBLE DOUBT, and although there are moments when her self-confidence falters, she triumphs in the end. I can’t recommend this novel too highly – it’s a work of genius. And it’s the first book I read in 2014, which I think is a GOOD OMEN.

December 29, 2013

‘Dated’ Books, Part Eight: Kangaroo

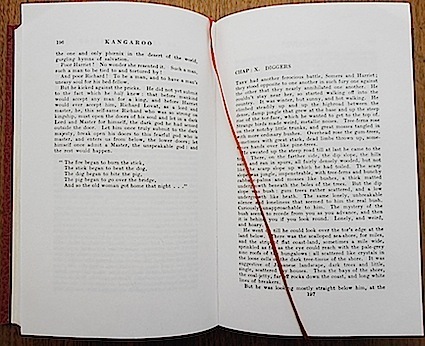

Is this book ‘dated‘ or merely peculiar? I certainly spent some time wondering how most modern-day publishers would react if sent a manuscript as rambling and self-indulgent as this one, and its discussions of race and gender definitely reflect common prejudices of the time. On the other hand, there are plenty of books first published in the 1920s that are an easy, enjoyable read, despite containing dated viewpoints. This is not one of them. Here are my thoughts on Kangaroo by D. H. Lawrence, but first, have a look at the splendid edition I read, courtesy of City of Sydney Libraries:

It says “AUSTRALIA’S GREAT BOOKS” on the cover, by the way. It’s actually not as old as it looks – this edition was published in 1992 – but it does seem to have reproduced the original typeset pages:

I’d wanted to read this for a while because I’d heard that it was inspired by D. H. Lawrence’s visit to Australia in the early 1920s and included descriptions of the early Fascist movement in Australia. In these respects, the book lived up to my expectations. The central character, Richard Lovat Somers, does seem to be a portrait of the author himself. Both were writers from working-class English backgrounds who married German women and suffered persecution in Britain during the First World War due to their anti-war stance, and who then travelled the world in a self-imposed exile. Unfortunately, Richard Lovat Somers turns out to be egomaniacal, bombastic and self-pitying, which makes spending four hundred pages in his company a fairly unpleasant experience. He pontificates at length about souls, dark gods, civilisation, sex, women, democracy, socialism, the Australian character and many other subjects in which he is a self-proclaimed expert. He records each passing thought at least five times, in much the same way, on the same page, then says the exact opposite in the next chapter, then changes his mind yet again. He is convinced of his own specialness – he is one of the few men with a soul, you see, so is uniquely qualified to determine what is best for Australia, and the working classes, and humankind.

The plot, such as it is, involves Richard arriving in Sydney and being introduced to ‘Kangaroo’, an aspiring politician who wants to impose his own benevolent brand of dictatorship on Australia. Richard is at first drawn to, then repulsed by, Kangaroo, after which he briefly flirts with a Communist leader whose ideas seem more “logical”. Mostly, though, Richard ponders whether he should devote his amazing intellectual gifts to politics at all, or simply let humankind go to pieces by itself. There is a brief flurry of action when the Fascists clash with the Communists, but this occurs very late in the book. The author does provide this warning to readers:

“Chapter follows chapter, and nothing doing . . .We can’t be at a stretch of tension all the time, like the E string on a fiddle. If you don’t like the novel, don’t read it.”

Unfortunately, this warning doesn’t appear until page 319, which is a bit late for most readers. This is pretty typical of the author’s contempt for the reader, though. Apart from subjecting us to pages and pages of Richard’s preaching and screeds of implausible dialogue between Richard and Kangaroo, Lawrence can’t even be bothered keeping track of character names (Richard, for example, is variously referred to as “Richard”, “Richard Lovat”, “Lovat”, “Lovat Somers” and “Somers”). The author makes other odd naming choices – for example, the town on the south coast of New South Wales where Richard and his wife rent a house is clearly Thirroul, but in this book it’s called ‘Mullumbimby‘. I can understand the author wanting to avoid using the real name of Thirroul, but why choose a name that belongs to a real, well-known and very different inland town in the far north of the state? It’s unnecessarily confusing.

I did love a lot of the beautiful descriptions of the Australian bush and the sea, but there were some puzzling mistakes. For example, he accurately describes a line of bluebottles on the beach, then confidently asserts they are “some sort of little octopus”. No, they’re not. And he describes a “kukooburra” as “a bird like a bunch of old rag, with a small rag of a dark tail, and a fluffy pale top like an owl, and a sort of frill round his neck”. Kookaburras have beautiful blue-edged wings, with tails striped in white, black and chestnut! They don’t look anything like old rags! I feel offended on behalf of the kookaburras of Australia.

It was interesting to read a European perspective of the early days of the Australian Federation and occasionally, Richard’s observations are really funny – for example, when he’s baffled by the way Australians use suit-cases instead of shopping baskets:

“A little girl goes to the dairy for six eggs and half a pound of butter with a small, elegant suit-case. Nay, a child of three toddled with a little six-inch suit-case, containing, as Harriet had occasion to see, two buns, because the suit-case flew open and the two buns rolled out. Australian suit-cases were always flying open, and discharging groceries or a skinned rabbit or three bottles of beer.”

Unfortunately, these sorts of observations are rare. Mostly, Richard is busy having this sort of conversation with Kangaroo:

‘Why,’ [Richard] said, ‘it means an end of us and what we are, in the first place. And then a re-entry into us of the great God, who enters us from below, not from above . . . Not through the spirit. Enters us from the lower self, the dark self, the phallic self, if you like.’

‘Enters us from the phallic self?’ snapped Kangaroo sharply.

‘Sacredly. The god you can never see or visualise, who stands dark on the threshold of the phallic me.’

‘The phallic you, my dear young friend, what is that but love?’

Richard shook his head in silence.

‘No,’ he said, in a slow, remote voice. ‘I know your love, Kangaroo. Working everything from the spirit, from the head. You work the lower self as an instrument of the spirit. Now it is time for the spirit to leave us again; it is time for the Son of Man to depart, and leave us dark, in front of the unspoken God: who is just beyond the dark threshold of the lower self, my lower self. There is a great God on the threshold of my lower self, whom I fear while he is my glory. And the spirit goes out like a spent candle.’

Kangaroo watched with a heavy face like a mask.

‘It is time for the spirit to leave us,’ he murmured in a somnambulist voice. ‘Time for the spirit to leave us.’

As for the dated aspects of this book – well, there are Richard’s 1920s prejudices about “Chinks” and “Japs” and “niggers”. He also declares that women are too emotional and irrational to be able to play any useful part in public life or even participate in serious conversations (which is pretty funny, given Richard’s wild mood swings and vacillating opinions). As offensive and ridiculous as these sections are, I don’t think they’re the main reason modern readers will be put off this novel. They’re more likely to be defeated by the almost non-existent narrative, the rambling, pretentious prose and the irritating main character. I’m quite proud of my self-discipline in finishing this book. Not recommended, except for D. H. Lawrence fans.

More ‘dated’ books:

1. Wigs on the Green by Nancy Mitford

2. The Charioteer by Mary Renault

3. The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault

4. Police at the Funeral by Margery Allingham

5. Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner

6. The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

7. Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome

December 22, 2013

My Favourite Books of 2013

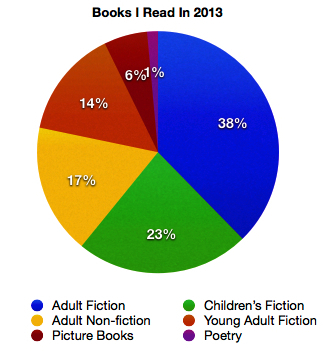

It’s not quite the end of the year, but here are the books I read in 2013 that I loved the most. But first – some statistics!

I’ve finished reading 69 books so far this year and I suspect I’ll squash another two or three novels in before New Year’s Eve. This total doesn’t include the two novels I gave up on (one because it was awful, the other because I just wasn’t in the right mood for it) or the novel I’m halfway through right now (Kangaroo by D. H. Lawrence, which deserves a blog post all of its own). So, what kind of books did I read this year?

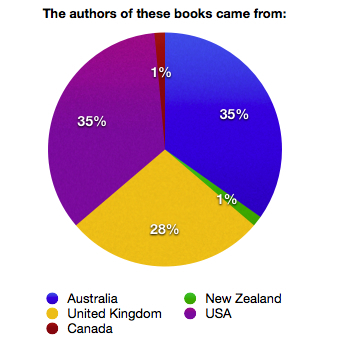

My reading this year was more culturally diverse than this pie chart would suggest – for example, I read quite a few books by writers who’d migrated from Asian countries to Australia or the UK, and I found those books really interesting. (I also read a couple of books by white writers about Aboriginal Australians and Pacific Islanders, which were less successful.)

This was the year of women writers, it seems.

Now for my favourites.

My favourite children’s and picture books

I really enjoyed Wonder by R. J. Palacio, even though it made me cry. Honourable mentions go to Girl’s Best Friend by Leslie Margolis, the first in a fun middle-grade series featuring Maggie Brooklyn, girl detective and dog walker, and Call Me Drog by Sue Cowing, an odd but endearing story about a boy who gets a malevolent talking puppet stuck on his hand. Picture books that entertained me this year included This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen, Mr Chicken Goes To Paris by Leigh Hobbs and The Oopsatoreum by Shaun Tan.

My favourite Young Adult novels

I loved Girl Defective by Simmone Howell and Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan. I was also impressed with Mary Hooper’s historical novel, Newes from the Dead (subtitled, Being a True Story of Anne Green, Hanged for Infanticide at Oxford Assizes in 1650, Restored to the World and Died Again 1665, which pretty much tells you what it’s about), although I’m not sure it was truly Young Adult, despite being published as such – some of the content seemed horrifyingly Adult to me.

My favourite novels for adults

I read some great grown-up novels this year. This may have been because I abandoned my usual method of choosing novels from the library (that is, selecting them at random from the shelves based on their blurbs) and started reserving books via my library’s handy online inter-library loan system, basing my choices on reviews, award short-lists and personal recommendations. I was happy to discover the novels of Madeleine St John and I especially liked The Women in Black and A Pure, Clear Light. I also enjoyed The Body of Jonah Boyd by David Leavitt (a very clever piece of writing which included some apt and cynical reflections on the business of creative writing), The Flight of the Maidens by Jane Gardam and Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. However, my favourite novel of the year would have to be Lives of Girls and Women by Alice Munro, who was recently awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

I read some great grown-up novels this year. This may have been because I abandoned my usual method of choosing novels from the library (that is, selecting them at random from the shelves based on their blurbs) and started reserving books via my library’s handy online inter-library loan system, basing my choices on reviews, award short-lists and personal recommendations. I was happy to discover the novels of Madeleine St John and I especially liked The Women in Black and A Pure, Clear Light. I also enjoyed The Body of Jonah Boyd by David Leavitt (a very clever piece of writing which included some apt and cynical reflections on the business of creative writing), The Flight of the Maidens by Jane Gardam and Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. However, my favourite novel of the year would have to be Lives of Girls and Women by Alice Munro, who was recently awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

My favourite non-fiction for adults

Among the memoirs I enjoyed this year were Births, Deaths, Marriages: True Tales by Georgia Blain and Growing Up Asian In Australia, edited by Alice Pung. I also liked Helen Trinca’s biography of Madeleine St John. The most interesting science-related books I read were Knowledge is Power: How Magic, the Government and an Apocalyptic Vision inspired Francis Bacon to create Modern Science by John Henry and I Wish I’d Made You Angry Earlier: Essays on Science, Scientists and Humanity by Max Perutz.

Hope you all had a good reading year and that 2014 brings you lots of great books. Happy holidays!

More favourite books:

Favourite Books of 2010

Favourite Books of 2011

Favourite Books of 2012

November 18, 2013

Miscellaneous Memoranda

- There’s an interesting article at Stacked by Kelly Jensen about ‘book packagers’ – that is, companies that come up with concepts for a book series (often targeting the Young Adult market), then hire writers to write the books. For example, The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and The Luxe series were both products of the book packaging company, Alloy Entertainment. The article reports that authors are now starting up these sorts of businesses themselves. There was James Frey’s company, Full Fathom Five, which attracted a lot of the wrong sort of attention a couple of years ago when it was revealed how little he pays his writers (and the writers don’t even get their name on the cover of the book). Now Lauren Oliver and Lexa Hillyer have had commercial success with Paper Lantern Lit. I’ve read a couple of the books mentioned in the article, unaware that they were ‘book packaging’ products, and found them to be competently written but fairly bland and forgettable. Still, I’m not exactly the target market.

- There’s also a fascinating post at Justine Larbalestier’s blog about the differences between YA and adult romance, and no, it’s not about how explicit the sex scenes are. I’m not sure I agree with all the assertions – for instance, is it really true that most adult romances are told from the perspective of both lovers, whereas YA is usually first person and a single point of view? However, I found the discussion really interesting, particularly the idea that eternal love and happily-ever-after endings rarely work well in YA novels.

- Over at Kill Your Darlings, there’s an interview with Dianne Touchell, who ran into some problems at a literary festival because her YA novel, Creepy and Maud, was judged to be a bit too confronting by the festival organisers. Cue discussion of whether YA novels today are too dark and depressing . . .

- There have also been a few (depressing) articles and posts lately about how difficult it is to earn a living as a professional writer. Tim Kreider at The New York Times reported how frequently he’s expected to write for no pay at all and Sherryl Clark wrote a post on her blog about acclaimed authors who have given up on writing altogether because they need to pay their bills. On the other hand, Paula Morris at New Zealand Books pronounced herself happy to be a part-time writer because there’s “something pathetic in the designation ‘full-time writer’ – it tries too hard, and manages to sound boastful and defensive at the same time”.

- Finally, best of luck to all those doing NaNoWriMo this month. (I don’t think I could write 50,000 words of novel in a single month. Well, I could, but at least 40,000 of the words would be complete rubbish.) To encourage you in your endeavours, here’s a lovely giant squid:

Captain Nemo and the Giant Squid, from the 1870 French edition of ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea’ by Jules Verne. Illustration by Alphonse de Neuville and Edouard Riou.

November 10, 2013

What I’ve Been Reading

I don’t have to do disclaimers for any of these books, because I don’t know any of the authors.

Growing Up Asian In Australia, edited by Alice Pung, was a fascinating collection of memoirs, short stories, essays and poems by a range of Asian-Australian writers, some of them famous (Shaun Tan, Tony Ayres, Cindy Pan, Benjamin Law and Kylie Kwong), some of them less well-known, but nearly all of them with interesting things to say about racism, cross-cultural communication and family life in Australia. As in any anthology, the quality of the writing was variable, but overall, I think the editor did a fine job of balancing powerful (and often depressing) pieces of writing with lighter, more entertaining, tales. I did wonder how ‘Asian’ would be defined and it turned out to mean mostly Australians of Chinese or Vietnamese descent, with a few writers whose families were from Korea or Thailand, which probably reflects the relative proportions of these ethnic groups in the Australian population. There were also a couple of Indians1 and I may have been biased towards them, but my favourite piece in the book was a short memoir by Shalini Akhil, in which she discusses her love of Wonder Woman with her Indian grandmother (“You can fight all the crime in the world, she said, but if you leave the house without putting your skirt on, no one will take you seriously”). They go on to imagine their own Indian version of Wonder Woman who “could wear a lungi over her sparkly pants, and that way if she ever needed seven yards of fabric in an emergency, she could just unwind it from her waist.” The grandmother also explains that rolling perfectly round rotis is a magic power, then cooks super-hero eggs with chilli for her granddaughter’s lunch. It was a very endearing piece of writing and now I need to track down this author’s novels.

A Few Right Thinking Men by Sulari Gentill has been on my To Read list for a while because, hey, a novel about 1930s Fascism, set in Sydney? Yes, please! And this turned out to be meticulously researched and absolutely fascinating, so I’m glad I finally got around to reading it. It’s the first in a historical crime series starring Rowland Sinclair, a gentleman artist with some disreputable friends, who sets out to investigate the murder of his beloved uncle and finds himself entangled in the conflict between Communists, Fascists and the authorities. I knew a little bit about the New Guard due to their hijacking of the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, but had no idea about their rival Fascist organisation, the Old Guard, or about how violent some of the confrontations became. It was also interesting to me to compare the Australian Fascist organisations to their British counterparts (which I’m more familiar with). While both had charismatic, upper-class leaders and were obsessed with nutty schemes, conspiracy theories and ridiculous uniforms, the New Guard forbade any female involvement, whereas women (many of them former suffragettes) were a significant part of Mosley’s British Union. I think it says something about how blokey Australia was (and is). I have to say that the writing in this novel was slightly clunky – a bit too much tell-not-show, a few too many information dumps – and I never quite worked out whether the leisurely pace of the mystery plot and the verbosity of the prose was a homage to early twentieth century literature or simply inadequate editing. However, Rowland and his friends were very appealing characters and the historical background was intriguing enough for me to consider reading more of this series.

A Few Right Thinking Men by Sulari Gentill has been on my To Read list for a while because, hey, a novel about 1930s Fascism, set in Sydney? Yes, please! And this turned out to be meticulously researched and absolutely fascinating, so I’m glad I finally got around to reading it. It’s the first in a historical crime series starring Rowland Sinclair, a gentleman artist with some disreputable friends, who sets out to investigate the murder of his beloved uncle and finds himself entangled in the conflict between Communists, Fascists and the authorities. I knew a little bit about the New Guard due to their hijacking of the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, but had no idea about their rival Fascist organisation, the Old Guard, or about how violent some of the confrontations became. It was also interesting to me to compare the Australian Fascist organisations to their British counterparts (which I’m more familiar with). While both had charismatic, upper-class leaders and were obsessed with nutty schemes, conspiracy theories and ridiculous uniforms, the New Guard forbade any female involvement, whereas women (many of them former suffragettes) were a significant part of Mosley’s British Union. I think it says something about how blokey Australia was (and is). I have to say that the writing in this novel was slightly clunky – a bit too much tell-not-show, a few too many information dumps – and I never quite worked out whether the leisurely pace of the mystery plot and the verbosity of the prose was a homage to early twentieth century literature or simply inadequate editing. However, Rowland and his friends were very appealing characters and the historical background was intriguing enough for me to consider reading more of this series.

Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan was a novel I didn’t expect to love as much as I did. Firstly, it has a stupid premise – two boys try to break the world record of more than thirty-two hours of continuous kissing2. Secondly, it’s a YA novel narrated by a chorus of old dead people in the second person. Thirdly, as much as I admire David Levithan’s prose, none of his books will ever pass the Bechdel test. He writes exclusively about gay, white, middle-class American boys3. Sympathetic girl characters, if they exist at all, are merely support crew (literally, in this particular novel). Despite all these ominous signs, I found myself engrossed in this book and was reduced to tears at several points where the dead men talked about their lives in an earlier, less tolerant society. I’m a bit older than David Levithan, old enough to remember the early years of the AIDS epidemic, when each edition of Sydney’s gay newspaper contained pages of obituaries and every community social function was a meeting about the Quilt Project or a fund-raiser for the HIV/AIDS ward at the local hospital, and this book brought back those days vividly for me. The chorus in Two Boys Kissing is there to explain to the teenage characters how much easier life is in the twenty-first century, and while I wholeheartedly agree (life is easier for most gay teenagers now than it was twenty-five years ago), I did wonder what teenage readers might think about this. So I was interested to read Anna Ryan-Punch’s review of the book in the latest edition of Viewpoint, in which she states:

Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan was a novel I didn’t expect to love as much as I did. Firstly, it has a stupid premise – two boys try to break the world record of more than thirty-two hours of continuous kissing2. Secondly, it’s a YA novel narrated by a chorus of old dead people in the second person. Thirdly, as much as I admire David Levithan’s prose, none of his books will ever pass the Bechdel test. He writes exclusively about gay, white, middle-class American boys3. Sympathetic girl characters, if they exist at all, are merely support crew (literally, in this particular novel). Despite all these ominous signs, I found myself engrossed in this book and was reduced to tears at several points where the dead men talked about their lives in an earlier, less tolerant society. I’m a bit older than David Levithan, old enough to remember the early years of the AIDS epidemic, when each edition of Sydney’s gay newspaper contained pages of obituaries and every community social function was a meeting about the Quilt Project or a fund-raiser for the HIV/AIDS ward at the local hospital, and this book brought back those days vividly for me. The chorus in Two Boys Kissing is there to explain to the teenage characters how much easier life is in the twenty-first century, and while I wholeheartedly agree (life is easier for most gay teenagers now than it was twenty-five years ago), I did wonder what teenage readers might think about this. So I was interested to read Anna Ryan-Punch’s review of the book in the latest edition of Viewpoint, in which she states:

“The use of their commentary comes off as heavy-handed, mawkish, and often didactic . . . there’s a patronising sense of authority, which is likely to put many readers on the defensive: ‘They are young. They don’t understand.’”

I can see that this book might not work for all readers, but it really had an impact on me. And I do agree with Anna Ryan-Punch that this book’s cover is “a literal and lovely picture of progress”.

Finally, I decided to start reading Lives of Girls and Women the day before the author, Alice Munro, won the 2013 Nobel Prize for Literature. This is because I am psychic. Not really. She’d been on my To Read list for ages, and now I’m kicking myself for not picking up one of her books sooner because this novel was utterly brilliant and I think it would have changed my life if I’d read it as a teenager. Her writing is so lucid and honest, each sentence beautiful and full of meaning – this is Serious Literature without being pretentious or incomprehensible or self-consciously ‘literary’. I was torn between wanting to linger upon each page to savour her wisdom and racing ahead to the next chapter to find out what would happen to Del, the teenage narrator, who is growing up in rural Canada in the 1940s and 1950s. I especially liked how the author described the limitations placed on women then (often by other women, not men) and how Del could so easily be a girl of today, her sexual desires clashing with what society determines is ‘correct’ for girls. This book was a bit like Anne Tyler combined with Margaret Atwood’s autobiographical short stories and they’re two of my favourite authors, so I think I should now read everything Alice Munro has ever written.

_____

Although I don’t tend to think of India as being part of Asia – to me, it’s geographically and culturally closer to the Middle East than to places like Japan and Singapore. But I’m aware most journalists, politicians and diplomats have a different viewpoint on this. ↩

I hate the whole idea of world records, but especially when it involves stretching enjoyable activities into ridiculous feats of endurance. Seriously, do something more constructive with your time and energy, people. ↩

It was nice to come across this interview with Malinda Lo, which suggests David Levithan has an awareness of this issue. ↩

October 27, 2013

The Creative Vision Versus The Marketing Department

If you know anything about the publishing industry, you’d be aware of how significant the marketing department has become in each large publishing house. The more difficult it becomes for publishers to make money from selling books, the more important become the people in publishing houses who work out what readers want (and persuade those readers to hand over some money). Publishers’ marketing departments determine how book covers should look, what time of year to publish certain books, and whether book trailers or magazine ads or blog posts will be the most effective method of attracting particular readers to books. But it isn’t just that the marketing people figure out how to sell a book once it’s been printed. Marketing departments also determine which books will get published in the first place. They (try to) predict whether there’ll be any demand in twelve months’ time for, say, gritty true crime or paranormal romance or travel memoirs, and then they sign up the appropriate manuscripts.

This is especially true regarding books for children and teenagers, because these books are often bought by people other than the intended audience – that is, the books are bought by parents, teachers, librarians and other adults, who may have quite different ideas about what’s ‘appropriate’ or ‘suitable’ for young readers. A publisher’s marketing department has a say in how many words a children’s book will have, how it will look, what its title will be – and, increasingly, what sort of content the book will have. If a manuscript is even slightly controversial, if it doesn’t fit neatly into a publishing genre, or if it doesn’t clearly appeal to a distinct marketing audience (for instance, boys aged 8-12), then that will make the book difficult to market. And why would a publisher take a chance on signing up that manuscript for a book deal, when they can instead publish a clone of whatever’s currently at the top of the children’s bestseller list, something that’s far more likely to make the publisher some money?

Without marketing departments, large publishing houses wouldn’t exist, because they wouldn’t make enough money to survive. Publishers can’t (and shouldn’t ) publish every manuscript they’re offered, and the marketing team helps determine whether manuscripts are self-indulgent rubbish or something that will find an audience and pay back its publishing costs. But that doesn’t mean marketing departments get it right all the time. If they did, all the books they’d worked on would be bestsellers, which clearly doesn’t happen. And sometimes, marketing departments get it spectacularly wrong, such as during the ‘whitewash’ controversy a few years ago. (In those cases, and there were more than one, the publishers’ thinking seemed to go: We want to sell lots of books. More books are bought by white people than by people who are not white. White people will only buy books about characters who look exactly the same as them. Therefore, on the rare occasion we publish books about characters who are not white, we must make sure we disguise the contents by putting white people on the cover.) In at least one whitewashing case, the public outcry led to the publisher changing the cover, but most of the time, people who buy books can’t protest because they have no idea about the decisions being made behind the doors of publishing houses.

I must emphasise that most people who work in the marketing departments of publishing houses love books and literature – otherwise, they’d take their skills to some other, more highly paid, section of the commercial world. However, there’s always going to be some conflict between the creative vision of individual writers and the objectives of publishers’ marketing departments, and the marketers nearly always win. This is why I absolutely love creative people – writers, musicians, artists, performers, whatever – who achieve great commercial success in spite of having the sort of creative ideas that give marketing departments conniptions.

For example, picture the faces of the marketing department at the BBC ten years ago, when two men turned up and said they wanted to make a television series for adults set in a zoo, featuring animation, songs, dancing wolves and a creature made of pink bubble gum. Or consider the marketing department of Mint Royale’s record company in 2003, who, according to director Edgar Wright, wanted him to cast “bigger” names in the video for Blue Song. He decided to stick with his original choice, the ‘unknown’ Noel Fielding and Julian Barratt. Smart move.

Noel Fielding1 and Julian Barratt went on to make three successful television series and sell out Wembley Arena, and they’re the only reason I’ve even heard of Mint Royale. Here endeth today’s lesson.

_____

If you’d like to see more of Noel Fielding’s dancing, here’s his poignant, heartfelt interpretation of Wuthering Heights. With cartwheels. And bonus Heathcliff appearance. ↩

October 8, 2013

Montmaray Book Giveaway Winners

The FitzOsbornes at War1 is out now in North America. Very exciting!

The FitzOsbornes at War1 is out now in North America. Very exciting!

_____

I’m pretty sure the book cover’s not as green and fuzzy as my picture suggests. Although maybe that’s a marketing strategy . . .

PERSON BROWSING IN BOOKSHOP: Hey, look at this weird book! Why is it all green and fuzzy? Hmm . . . Kirkus says on the cover that it’s “absorbing, compelling and unforgettable.” I must buy this book at once!

RANDOM HOUSE MARKETING PERSON HIDING BEHIND SHELVES: Rubs hands with glee. Places another green, fuzzy copy of ‘The FitzOsbornes at War’ on shelf. ↩

September 23, 2013

The Great Big Montmaray Book Giveaway

The paperback edition of The FitzOsbornes at War comes out in North America in two weeks, so I thought I’d hold a Montmaray giveaway to celebrate.

Would you like to win one of the Montmaray books pictured above? If so, leave a comment below telling us about one of your favourite books, one that you’d like to recommend to other readers. You can write as much or as little as you want about the book. It can be any sort of book at all (although, ideally, it will be a book we haven’t heard much about, one that you think deserves more appreciation). I’ll choose three comments at random, and those three comment-writers can then let me know which Montmaray book they’d like me to send them. Of course, you may have read all the Montmaray books already, but perhaps you borrowed them from the library and would like your own, personally signed, copy? Or perhaps you’d like to give one to a friend?

Conditions of entry:

1. This is an international giveaway. Anyone can enter.

2. Make sure the email address you enter on the comment form is a valid one that you check regularly, so I can contact you if you win. No one will be able to see your email address except me, and I won’t show it to anyone else. Please don’t include your real residential or postal address anywhere in the comment. However, it would be nice if you mentioned which country you live in, because I’m curious about who reads this blog.

3. The three winners will be chosen at random, unless there are three or fewer comments – in which case, it won’t be random and all will win prizes.

4. Each winner can choose one of the Montmaray hardcovers or paperbacks pictured above, or one of the CD audiobooks of either A Brief History of Montmaray or The FitzOsbornes in Exile (not pictured above, but they do exist). See my book page for a list of the available books and audiobooks. Please note that I have lots of the North American editions, but not so many of the early Australian books. I’ll try to give each winner his or her first choice of book, but if all three winners want, say, an Australian first edition of A Brief History of Montmaray, then whoever emails me back first will get their first choice and the others might have to choose a different Montmaray book.

5. Entries close at 9:00 am Eastern Daylight Time in the US on the 8th of October, 2013, which is when the Ember paperback edition of The FitzOsbornes at War goes on sale in North America. The three giveaway winners will be emailed then, and I will post off the winners’ books as soon as possible after that.

6. This contest and/or promotion is not sponsored or authorised by Random House Australia. Random House Australia bears no legal liability in connection with this contest and/or promotion.

Off you go – recommend a book for us in the comments below. Good luck!

September 19, 2013

Science Reads: ‘Chocolate Consumption, Cognitive Function, and Nobel Laureates’ by Franz H. Messerli

To end Science Reads Week on a lighter note, I’d like to draw your attention to an article1 published in The New England Journal of Medicine last year, which investigates whether eating chocolate makes you smarter. Dr Messerli notes that dietary flavanols, found in dark chocolate, green tea and red wine, have been shown to improve the blood supply to the brain and cause rats to perform better on cognitive tests. He also notes that countries with a high consumption of chocolate, particularly Switzerland, tend to produce a lot of Nobel laureates. When he analyses the data, he finds “a surprisingly strong correlation” between chocolate intake and the number of Nobel Prizes won in a given country. Unfortunately, Sweden messes up his results. But don’t worry, Dr Messerli has an explanation:

“Given its per capita chocolate consumption of 6.4 kg per year, we would predict that Sweden should have produced a total of about 14 Nobel laureates, yet we observe 32. Considering that in this instance the observed number exceeds the expected number by a factor of more than 2, one cannot quite escape the notion that either the Nobel Committee in Stockholm has some inherent patriotic bias when assessing the candidates for these awards or, perhaps, that the Swedes are particularly sensitive to chocolate, and even minuscule amounts greatly enhance their cognition.”

Yes, the article is completely tongue-in-cheek. However, I feel this issue needs further investigation, so I’m off to eat some Lindt 70% Dark Chocolate. Purely in the interests of scientific investigation, you understand. Happy ‘Science Reads Week’ to you all, and may your own scientific investigations be similarly delicious!

_____

Sorry, this article is now only available to NEJM subscribers. ↩

September 18, 2013

Science Reads: ‘Knowledge is Power: How Magic, the Government and an Apocalyptic Vision inspired Francis Bacon to create Modern Science’ by John Henry

Today’s Science Read is an odd but fascinating book about Francis Bacon, who is often credited with being the founder of ‘Modern Science’, although the truth is far more complex. Now, I have to admit that my knowledge of Francis Bacon was fairly patchy before I picked up this book. My mental card file on him looked something like this:

FRANCIS BACON

- Lived in 1500s? 1600s?

- Wrote some books about philosophy

- Jumped out of his carriage to grab a chicken, kill it and stuff it with snow, in order to see if ice could preserve flesh; consequently died of pneumonia due to exposure

- Not to be confused with the Francis Bacon who painted all those grotesque portraits

In other words, I knew almost nothing about him. However, I can now reliably inform you that Francis Bacon (no relation to the artist) was born in 1561; became Lord Chancellor to King James I; wrote a LOT of books, including one of the first Utopian novels; influenced a range of scientists, from Newton to Darwin, and inspired the establishment of the Royal Society, the oldest and most prestigious scientific institution in Britain; and died in 1626, although his death probably had nothing to do with iced-chicken experiments.

John Henry gives a clear description of Bacon’s main themes, which were that society was on the verge of a flowering of knowledge about how the universe worked; that this knowledge should be used for the benefit of humankind; and that science would be best developed within a bureaucratic structure funded by the government but free of political and religious bias, and staffed by a huge army of workers gathering, tabulating and interpreting information. Even Henry acknowledges that important scientific advances have never happened within this type of bureaucratic structure, but he argues convincingly that Bacon’s ideas were very influential, if sometimes misinterpreted, by philosophers and scientists during the Enlightenment and afterwards.

John Henry gives a clear description of Bacon’s main themes, which were that society was on the verge of a flowering of knowledge about how the universe worked; that this knowledge should be used for the benefit of humankind; and that science would be best developed within a bureaucratic structure funded by the government but free of political and religious bias, and staffed by a huge army of workers gathering, tabulating and interpreting information. Even Henry acknowledges that important scientific advances have never happened within this type of bureaucratic structure, but he argues convincingly that Bacon’s ideas were very influential, if sometimes misinterpreted, by philosophers and scientists during the Enlightenment and afterwards.

Henry also does an excellent job of describing Bacon’s world, one quite alien to those of us living in twenty-first century secular democracies. For example, in Bacon’s time, it was completely rational to believe in God and whatever the Church currently decreed was a ‘fact’ (regardless of whether it really was true), because otherwise, you’d find yourself convicted of heresy and burnt at the stake. Words such as ‘magic’, ‘science’ and ‘atheist’ had completely different meanings then. ‘Magic’, for example, was not about supernatural powers, but about discovering the ‘correspondences’ between natural substances (for example, between magnets and iron) and ‘natural magic’ was what we might think of as primitive science. While a magician might (unwisely) choose to summon a demon, this would only be to help the magician learn about these natural correspondences more quickly. A demon had knowledge but no supernatural powers and could not do anything miraculous, and the Church frowned upon demonology only because demons were known to exploit humans and could endanger a magician’s immortal soul. Henry also explains how Bacon’s devout Calvinist upbringing and conviction that the End of Days was nigh1 had a significant influence upon his philosophy.

The design of this book was a bit odd, and at first I wondered if it was self-published, but no, it seems it’s part of a series of science-themed books published by Icon Books in the UK and Totem Books in the US. There was a glossary, but no index; there were a few footnotes, but they referred to only four texts; there was some very dense and academic information, but it was presented in a conversational style with lots of droll asides from the author. It’s as though the publishers weren’t exactly sure who the audience for this book would be, but I found it very interesting and readable. Those who know a lot about Francis Bacon probably won’t find much new in this book, but I’d recommend this for those who don’t know much about him but are interested in the history of science.

Tomorrow in Science Reads: Chocolate Consumption, Cognitive Function, and Nobel Laureates by Franz H. Messerli

_____

While ‘apocalypse’ implies destruction and chaos to us, to Bacon it meant a time when the old, flawed world would be replaced with a glorious new world, full of knowledge and contentment. While it was true that this would mean the destruction of unworthy humans (Catholics, Jews, Muslims, heathens, etc), Bacon knew that he, as an Englishman and the ‘right’ sort of Protestant Christian, would be one of the saved, so he eagerly awaited Judgement Day. ↩