Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 29

September 9, 2012

The RAF Pilots’ Song, Plus Some WWII Girl Power

Did you know that, during the Second World War, some of the brave fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force formed their own boy band? And, when not shooting down Luftwaffe bombers, would dance in front of their Spitfires, singing harmonies about, among other things, Douglas Bader’s legs (“They’re not real”)? No, neither did I!1 But I think Toby FitzOsborne would approve. Take that, Hitler!

And let’s not forget the contributions made by British women during the war. If you think they were all stuck in the kitchen, you haven’t seen this! Or read The FitzOsbornes at War, which is all about girls being awesome in wartime, and is published in North America next month, and looks like this:

‘The FitzOsbornes at War’, published in North America on October 9, 2012

_____

Thank you to Kate Constable, whose informative and entertaining blog post alerted me to the fact that the Horrible Histories books have now been turned into a TV series. I had no idea! I would have left a comment on her blog post as well, but Blogspot doesn’t like me and refuses to accept my comments. ↩

September 5, 2012

The Fishing Fleet: Husband-Hunting in the Raj by Anne de Courcy

I’ve enjoyed Anne de Courcy’s previous social histories and biographies, so when I saw her latest book was about India, I was keen to read it. As usual, her subject is posh English people, circa 1850 – 1950, but this time she has focussed on the young English women who sailed to India to find themselves husbands. The first such ‘Fishing Fleet’ arrived in Bombay in 1671, the women having been paid generous allowances by the East India Company. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century, there was no need to provide incentives to prospective brides. The only respectable career for a Victorian ‘gentlewoman’ was that of wife and mother, but there were far more unmarried women than eligible bachelors in England. Women who were neither rich nor pretty enough to snare a husband knew they’d have a much better chance in India, where white men outnumbered white women by four to one and were forbidden (by their terms of employment and social custom) from marrying females with any tinge of ‘native blood’.

I’ve enjoyed Anne de Courcy’s previous social histories and biographies, so when I saw her latest book was about India, I was keen to read it. As usual, her subject is posh English people, circa 1850 – 1950, but this time she has focussed on the young English women who sailed to India to find themselves husbands. The first such ‘Fishing Fleet’ arrived in Bombay in 1671, the women having been paid generous allowances by the East India Company. However, by the middle of the nineteenth century, there was no need to provide incentives to prospective brides. The only respectable career for a Victorian ‘gentlewoman’ was that of wife and mother, but there were far more unmarried women than eligible bachelors in England. Women who were neither rich nor pretty enough to snare a husband knew they’d have a much better chance in India, where white men outnumbered white women by four to one and were forbidden (by their terms of employment and social custom) from marrying females with any tinge of ‘native blood’.

Anne de Courcy uses memoirs, letters, diaries and interviews to provide fascinating details of these ‘husband-hunters’. First, there was the arduous sailing trip (all the way around Africa before the Suez Canal opened in 1869), the poor women having to contend with cramped living space, sea sickness, limited fresh food and other inconveniences:

“Fresh water for washing clothes was in such short supply that many women who knew they were going to travel saved their most worn underwear and then discarded it overboard on the voyage, leaving, one imagines, a trail of dirty, threadbare nightdresses across the Indian Ocean.”

Arriving in Bombay or Calcutta, the young woman was often overwhelmed by the heat, the dust, the smells, the “teeming mass of people”. She was then flung into India’s version of ‘the Season’, attending (depending on her social rank) Viceregal balls and banquets, dinner parties, tea dances, picnics, tennis parties and tiger-hunts. Couples often became engaged after only one or two brief meetings, the men desperate for companionship after years of celibacy, the women anxious to avoid the mortification of being sent home as a ‘Returned Empty’ (that is, a failed husband-hunter). Most military and Indian Civil Service men weren’t permitted to marry until they were at least thirty, which meant bridegrooms were often several decades older than their teenage brides and could be unwilling or unable to change their bachelor lifestyles. One beautiful and cosseted young woman, who wed in 1932, found herself living on a remote tea plantation, miles from her nearest white neighbour, with no transportation, no electricity and nothing to do. Her much older husband spent all his time working or hunting with his hounds and horses and forgot her twenty-first birthday, and her child was delivered by the local vet because there was no doctor available. Still, “Sheila was a true daughter of the Raj, brave and uncomplaining” and later told her daughter that she always dressed in an evening gown for dinner because “it was felt that one must keep up standards and not let oneself go native.”

Actually, Sheila had it relatively easy. Other women were shot at by mutinous ‘natives’, while some were caught in avalanches and earthquakes. Women died of cholera, smallpox, malaria and even bubonic plague. Infants were particularly vulnerable to diseases, and those who survived were routinely sent off to boarding school in England from the age of six, so their mothers had the agonising choice of being separated for years at a time from either their husband or their small children. And then there was the wildlife – panthers that snatched pet dogs from gardens and golf courses, snakes that slithered up through drainage holes into bathrooms, scorpions hidden in shoes, rats under the bed and monkeys that stole silver spoons from the table. One young woman awoke to find a civet cat drinking from her bedside glass of milk.

What I found most interesting was how British India was far more patriarchal and snobbish than Britain itself. By the twentieth century, it was possible for a working-class man with a great deal of intelligence, talent and luck to rise as high as Prime Minister, and for a well-born woman to become a Member of Parliament. This was impossible in India, where women had no status at all and “the hierarchy of the Raj position was fixed, according to service, rank and seniority in an unalterable grading . . . within which there was room for petty nuances that could be painful and damaging.”

Everyone was obsessed with their own and everyone else’s social precedence, and in a small society where nothing was private, it was thought essential to ‘keep up with the Joneses’. Those who could barely afford it still kept polo ponies, paid expensive subscriptions to clubs and held elaborate dinner parties, and there was little tolerance for those regarded as ‘intellectuals’.

The stories in this book are mostly of upper-class British women, rather than, say, the women who went to India as teachers, nurses and missionaries. There are also few mentions of Indians, apart from some anonymous, silent servants and the Maharajah of Patiala, who married Miss Florence Bryan in 18931. The author clearly feels that Britain’s colonisation of India was a very good thing – after all, most of the Indian rulers prior to colonisation were cruel despots (true, but so were the rulers of most countries in the eighteenth century) and the British “left India, after independence, with an enviable infrastructure, a democratic Government and a common language”. (The book makes only passing mention of the terrible famines that resulted from the British forcing Indian farmers to grow jute and cotton, rather than food2, and of the violent suppression of pro-independence Indians3.)

Despite these reservations, the book is recommended for those interested in reading about British women’s experiences in India. But I think novels can be just as useful for this purpose, so here are some of my favourites:

Despite these reservations, the book is recommended for those interested in reading about British women’s experiences in India. But I think novels can be just as useful for this purpose, so here are some of my favourites:

- Heat and Dust by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

- A Passage to India by E. M. Forster

- The Jewel in the Crown and other novels in the Raj Quartet by Paul Scott

- Black Narcissus by Rumer Godden4

- Coromandel Sea Change by Rumer Godden

(Actually, read all of Rumer Godden’s India books, because she’s brilliant. Anne Chisholm also wrote an excellent biography, Rumer Godden: A Storyteller’s Life.)

- And for a slightly different look at Europeans in India, there’s also Baumgartner’s Bombay by Anita Desai.

_____

It was a “brief and unhappy” marriage. She was shunned by both Indians and Europeans, her infant son was poisoned, and she died of pneumonia three years later. ↩

Up to ten million Indians died in the famine of 1876-8, and a similar number in 1899-1900. ↩

For example, hundreds died at Amritsar in 1919, when British troops fired on unarmed protesters. ↩

Black Narcissus was made into a hilariously bad film in 1947. In one memorable scene, the mad nun flees through a Himalayan ‘jungle’ inhabited by kookaburras. ↩

August 28, 2012

Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA by Brenda Maddox

I’ve just finished reading an excellent biography of Rosalind Franklin, the scientist who received no credit (at least, not during her lifetime) for her work on the structure of DNA. James Watson and Francis Crick appropriated her data without her knowledge or consent, and used it to construct their double helix model of DNA. When they published their work in Nature in 1953, they mentioned the DNA research being carried out at her lab in King’s College, but falsely claimed that they “were not aware of the details of the results presented there when we revised our structure”. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962, but neglected to mention Rosalind Franklin’s name in their speeches, and Watson’s 1968 book, The Double Helix, portrayed her as a dowdy shrew who couldn’t understand her own data.

However, Rosalind Franklin was far more than “the Sylvia Plath of molecular biology, the woman whose gifts were sacrificed to the greater glory of the male”. Brenda Maddox paints a vivid portrait of the woman who

However, Rosalind Franklin was far more than “the Sylvia Plath of molecular biology, the woman whose gifts were sacrificed to the greater glory of the male”. Brenda Maddox paints a vivid portrait of the woman who

“achieved an international reputation in three different fields of scientific research while at the same time nourishing a passion for travel, a gift for friendship, a love of clothes and good food, and a strong political conscience [and who] never flagged in her duties to the distinguished Anglo-Jewish family of which she was a loyal, if combative, member.”

Rosalind was an “alarmingly clever” girl, the eldest daughter in a family of philanthropists that had made a fortune from banking and publishing. Her father was politically conservative, but there were a number of left-wing rebels in the family1. The book contains wonderful descriptions, often from Rosalind’s own letters, of her childhood in Notting Hill and of her time at St Paul’s Girls’ School, which was then one of the few schools that prepared girls for a career. She went up to Cambridge in 1938, as bomb shelters were being dug in Hyde Park and her family were taking in Jewish refugees from Austria. By the end of the war, she had a PhD in physical chemistry and was working on war-related research about coal. After a few years in Paris, she returned (reluctantly) to London, where the focus of her research changed to the structure of DNA, and then the structure of viruses.

Don’t be put off, thinking this book is filled with Difficult Science. I’m hardly an expert in X-Ray crystallography, but I was able to follow the progress of Rosalind’s research quite easily, thanks to Maddox’s clear descriptions and diagrams. It probably helps to have some interest in DNA, but you can skim the scientific descriptions if you must. What is really fascinating (and infuriating) is Maddox’s account of the experiences of women scientists in the 1940s and 1950s – how they were refused admission to the Royal Society until 19452, missed out on nominations for awards and research positions, were paid less than men for equal work, and were refused admission to university common rooms and research facilities3. Rosalind, who was a perfectionist and was widely regarded as ‘prickly’, often antagonised senior male researchers. For example, Norman Pirie, a specialist in plant viruses, wrote her a patronising letter in 1954, criticising her data that showed tobacco mosaic virus rods were all the same length. As it turned out, she was right and he was wrong. But he was also friends with the head of the council that was funding her research, which subsequently refused to provide any more money, even though her work had the potential to lead to a cure for a range of viral diseases, including polio.

Despite her constant battles at work, Rosalind comes across as a woman who embraced life. She was wonderful with children, she loved to cook elaborate dinners for her friends, and her greatest joy was hiking trips into the mountains. She made two journeys across the United States in the 1950s, and her letters about her travels are affectionate and amusing. She died tragically young, at the age of only thirty-seven, of ovarian cancer. The head of her research facility, J.D. Bernal, wrote that it was “a great loss to science”. He praised her “single-minded devotion to scientific research”, noting that

“As a scientist Miss Franklin was distinguished by extreme clarity and perfection in everything she undertook. Her photographs are among the most beautiful X-Ray photographs of any substance ever taken.”

Despite James Watson’s4 many attempts to belittle Rosalind’s intelligence and personality after her death, the world eventually came to recognise the value of her work. Buildings at St Paul’s Girls’ School, Newnham College and King’s College are now named after her, and her portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London – below those of Watson and Crick, of course.

Highly recommended if you’re interested in science, or feminism, or simply want to read the story of a fascinating, forthright young woman.

_____

One uncle was “a pro-suffragist who in 1910 had accosted the then Home Secretary Winston Churchill on a train and attempted to strike him with a dogwhip because of Churchill’s opposition to women’s suffrage. (Churchill was unharmed by the attack and continued on to the dining car.)” One aunt was a “socialist with cropped hair and pinstriped clothes” (and a girlfriend), while another aunt was a trade unionist who married a diplomat and caused a scandal by “driving her own car”. ↩

In 1902, Hertha Ayrton, engineer and physicist, was refused admittance to this “citadel of Britain’s scientific elite … on the ground that as a married woman, she was not a legal person”. ↩

This wasn’t just in Britain. Women were not allowed to set foot inside the physics building at Princeton in the 1950s, and were banned from working as physics instructors at Harvard until the 1970s. ↩

Apart from his misogyny, Watson also refuses to hire “fat people” and thinks Africans are less intelligent than white people. What a charming man. ↩

August 19, 2012

Saffy’s Angel by Hilary McKay

I absolutely loved this book. I’d order you all to read it, except most of you probably have 1. For those who haven’t, Saffy’s Angel is a clever, funny, touching story about the Casson family. The parental figures are all either vague, absent or dead, but fortunately, the children are resourceful and clever. The eldest, Caddy, is beautiful, kind and not nearly as dim as she first appears. When she’s not looking after the younger children, she’s tending to her guinea pigs (“occasionally they escaped and flocked and multiplied over the lawn like wildebeest on the African plains”) or having driving lessons. She has had ninety-six lessons and still can’t reverse or turn right (coincidentally, she’s in love with her gorgeous driving instructor). Indigo, the only boy, is gentle, sensitive and caring2, and keeps himself busy “curing himself of vertigo for when he becomes a polar explorer”. Rose, the youngest, is artistic, determined and very good at managing (or manipulating) their parents. Then there’s Saffy, who discovers that she’s adopted and refuses to believe the others when they insist she really is a Casson. With the help of her best friend, Wheelchair Girl, Saffy sets out to find the stone angel that her beloved grandfather bequeathed to her and she discovers just how much she means to her family.

I absolutely loved this book. I’d order you all to read it, except most of you probably have 1. For those who haven’t, Saffy’s Angel is a clever, funny, touching story about the Casson family. The parental figures are all either vague, absent or dead, but fortunately, the children are resourceful and clever. The eldest, Caddy, is beautiful, kind and not nearly as dim as she first appears. When she’s not looking after the younger children, she’s tending to her guinea pigs (“occasionally they escaped and flocked and multiplied over the lawn like wildebeest on the African plains”) or having driving lessons. She has had ninety-six lessons and still can’t reverse or turn right (coincidentally, she’s in love with her gorgeous driving instructor). Indigo, the only boy, is gentle, sensitive and caring2, and keeps himself busy “curing himself of vertigo for when he becomes a polar explorer”. Rose, the youngest, is artistic, determined and very good at managing (or manipulating) their parents. Then there’s Saffy, who discovers that she’s adopted and refuses to believe the others when they insist she really is a Casson. With the help of her best friend, Wheelchair Girl, Saffy sets out to find the stone angel that her beloved grandfather bequeathed to her and she discovers just how much she means to her family.

I was filled with admiration for how well Hilary McKay told this story. The story’s structure, the pacing, the voice of the narrator – all worked brilliantly, in my opinion. The Cassons were quirky and entertaining, but never irritating or implausible3. Saffy’s search for her lost angel was moving, but never tipped over into soppy sentimentality. And I loved that Wheelchair Girl was neither a victim nor a saint, but a flawed, fiercely independent girl who’d learned to turn everyone else’s pity around to her own (Machiavellian) advantage.

Above all, this book was very, very funny. There was one part where I was laughing so hard that I was crying, and had to keep putting down the book to wipe my eyes so I could see 4. I am very happy that there are five more books about the Cassons, as well as another two series by the author, The Exiles and Porridge Hall.

_____

as it was published more than a decade ago, and is quite well-known, and also won the 2002 Whitbread Children’s Book Award ↩

I love Indigo. He’s my favourite. ↩

Okay, I got irritated at Bill, the father, quite a lot, but he was meant to be annoying, and he was probably the most realistic character in the book. I know some men who are just like him. ↩

For those who’ve read the book, it’s the bit where Caddy takes them on a long car journey, and Indigo, who has “photographic ears”, is doing impressions of Michael (“Don’t call me darling, I’m a driving instructor”), while Rose holds up helpful signs for the other motorists, warning them about Caddy’s driving skills:

THERE WAS A FOX

SQUASHED FLAT

POOR FOX

SHE IS CRYING

SO YOU HAD BETTER NOT

TRY PASSING US YET

I WILL TELL YOU WHEN IT IS SAFE

IT WILL BE ALL RIGHT NOW

HELLO

WE ARE GOING TO WALES ↩

August 12, 2012

‘Dated’ Books, Part Six: The Wind in the Willows

1 I recently had occasion to re-read The Wind in the Willows2 by Kenneth Grahame, and realised at once that it would make an excellent addition to my ‘Dated’ Books series. (For the benefit of those new to the series, ‘dated’ means ‘of its time, not ours’. ‘Dated’ books can be offensive to modern sensibilities, or they can be charmingly nostalgic, or they can simply be . . . odd. And some, like The Wind in the Willows, are all of these things.)

I picked up The Wind in the Willows because I’d been asked to read a section of it aloud as part of the National Bookshop Day celebrations3. Although I’d read the book as a child, it hadn’t made much of an impression on me, so I figured I’d better have another look, just in case there were any ‘difficult’ words. Well! Here are some of the words I found in The Wind in the Willows. How many can you correctly pronounce and define, without looking them up in a dictionary?

provender

miry

bole

freshet

asperities

appurtenance

expatiate

wonted

casque

murrain

runnel

benison

corsair

osier

sward

caique

corselet

gunwale

accoutrement

unction

While the general meaning of the words could usually be inferred from the context, I had to look up several of the boating-related terms. For example, a ‘caique’, pronounced ‘kah-eek’, is either a rowboat used on the Bosporus or a small Mediterranean sailing ship, while ‘gunwale’, the edge of a boat formerly used to support guns, is pronounced ‘gunnel’. That’s not counting all the French phrases (table d’hôte, en pension), off-hand references to Norse legends (Sigurd) and Old English names of flora and fauna that I came across in the book. Now, imagine an author of today using those words in a manuscript aimed at primary school children, then trying to get the manuscript published. 4 It says something (probably something unflattering) about expectations for child readers these days. I think it also means The Wind in the Willows is more of a read-aloud-to-young-readers book now (although it depends on the particular child, of course – there are some who’d love figuring out the unfamiliar vocabulary for themselves).

The second thing I noticed about the book is how uneven it is, regarding tone and pace. There are a number of funny, exciting chapters involving Toad’s misadventures, in which he steals a car, insults a policeman, escapes from prison, hitches a ride on a steam train, gets tossed into a canal, steals a horse and finally makes his way home, only to find that his mansion has been invaded by weasels. There’s also the thrilling tale of Mole and Ratty getting lost in the Wild Wood during a snowstorm. Fortunately, Mole trips over a door-scraper hidden under the snow, although he fails to understand the significance of this:

“‘But don’t you see what it MEANS, you—you dull-witted animal?’ cried the Rat impatiently.

‘Of course I see what it means,’ replied the Mole. ‘It simply means that some VERY careless and forgetful person has left his door-scraper lying about in the middle of the Wild Wood, JUST where it’s SURE to trip EVERYBODY up. Very thoughtless of him, I call it. When I get home I shall go and complain about it to—to somebody or other, see if I don’t!’

‘O, dear! O, dear!’ cried the Rat, in despair at his obtuseness. ‘Here, stop arguing and come and scrape!’ And he set to work again and made the snow fly in all directions around him.

After some further toil his efforts were rewarded, and a very shabby door-mat lay exposed to view.

‘There, what did I tell you?’ exclaimed the Rat in great triumph.

‘Absolutely nothing whatever,’ replied the Mole, with perfect truthfulness. ‘Well now,’ he went on, ‘you seem to have found another piece of domestic litter, done for and thrown away, and I suppose you’re perfectly happy. Better go ahead and dance your jig round that if you’ve got to, and get it over, and then perhaps we can go on and not waste any more time over rubbish-heaps. Can we EAT a doormat? Or sleep under a door-mat? Or sit on a door-mat and sledge home over the snow on it, you exasperating rodent?’

‘Do—you—mean—to—say,’ cried the excited Rat, ‘that this door-mat doesn’t TELL you anything?’

‘Really, Rat,’ said the Mole, quite pettishly, ‘I think we’d had enough of this folly. Who ever heard of a door-mat TELLING anyone anything? They simply don’t do it. They are not that sort at all. Door-mats know their place.’”

But then, interspersed with the humour and excitement of these adventures, are entire chapters wallowing in cloying Victorian sentimentality. Most of these are Romantic odes to Nature:

“‘This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,’ whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. ‘Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!’

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror—indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy—but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near. With difficulty he turned to look for his friend and saw him at his side cowed, stricken, and trembling violently. And still there was utter silence in the populous bird-haunted branches around them; and still the light grew and grew […] All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

‘Rat!’ he found breath to whisper, shaking. ‘Are you afraid?’

‘Afraid?’ murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. ‘Afraid! Of HIM? O, never, never! And yet—and yet—O, Mole, I am afraid!’

Then the two animals, crouching to the earth, bowed their heads and did worship.”

Can you believe these two excerpts are about the same characters and come from the same book? And then, directly after Rat and Mole’s trembling glimpse of The Piper At The Gates of Dawn, we return to Toad escaping from prison, disguised as a washerwoman. Still, this might not count as evidence of the book’s datedness – it’s possibly just a sign of Kenneth Grahame’s eccentricity.

One definite sign of both datedness and the author’s oddness is the book’s attitude to girls and women. Not one of the animal characters – Mole, Rat, Toad, Badger, Otter, Portly, the Wayfarer Rat or the Chief Weasel – is female. When baby Portly goes missing, it’s his father, not his mother, who frets about him, searches for him and keeps a lonely vigil at the ford waiting for his return. The only female characters with speaking roles are the gaoler’s daughter (described as “a pleasant wench”) and an unnamed barge-woman (described by Toad as a “common, low, FAT barge-woman”). When other females are mentioned, it’s always with contempt. Toad’s friends try to get him to give up his dangerous motoring escapades by warning him that he could end up “in hospital, being ordered about by female nurses”. Then there’s this charming exchange between Toad and the barge-woman:

“‘But you know what GIRLS are, ma’am! Nasty little hussies, that’s what I call ‘em!’

‘So do I, too,’ said the barge-woman with great heartiness. ‘But I dare say you set yours to rights, the idle trollops!’”

Oh, dear. Apparently, when Kenneth Grahame “sent the manuscript off to his agent, he told him proudly that it was ‘clean of the clash of sex’.”5 By ‘the clash of sex’, I assume he meant ‘any positive references to girls or women’. Still, you have to feel sorry for the man, because he had a very troubled life. His mother died when he was five, his father proceeded to drink himself to death, and his guardians refused to send him to Oxford, ordering him instead to work at the Bank of England, where he was shot at by a ‘Socialist Lunatic’. Fortunately, all the bullets missed, but Grahame retired to the country soon after this to live in “a loveless marriage with a hysterical hypochondriac” and look after their disturbed young son, Alastair. One of Alastair’s favourite games involved “lying down in the road in front of approaching cars and forcing them to stop”, and he eventually killed himself at the age of nineteen by lying in front of a train. It was no wonder Kenneth Grahame wanted to escape into a world where animals lived in snug little houses by a river bank and spent all their time “messing about on boats” and having delightful picnics.

Despite the difficulties I had with this book, I am curious about this annotated volume, edited by Seth Lerer (if only because it features those lovely original illustrations by Ernest H. Shepard).

More ‘dated’ books:

1. Wigs on the Green by Nancy Mitford

2. The Charioteer by Mary Renault

3. The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault

4. Police at the Funeral by Margery Allingham

5. Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner

_____

I have finally learned how to do proper footnotes in WordPress. Be afraid. Be very afraid. ↩

Now available in a new Vintage Classics edition. ↩

at Shearer’s Bookshop in Norton Street, Leichhardt, which now has a large selection of my signed books. ↩

I write for teenagers, not children, but still had a minor editorial skirmish over ‘enervating’. It appears the Australian edition of The FitzOsbornes in Exile, but was replaced with ‘tiring’ in the North American edition. ↩

All the biographical quotes in this paragraph are from this fascinating article by John Preston, entitled Kenneth Grahame: Lost in the Wild Wood. ↩

August 8, 2012

Oh, Look, Another Book Giveaway!

Historical Tapestry is giving away a copy of the lovely Vintage Classics edition of A Brief History of Montmaray. It’s an international giveaway and entries close on 19th August. (They also have lots of interesting reviews and articles about historical fiction. Including one by me, which is, not surprisingly, about 1930s England.)

August 6, 2012

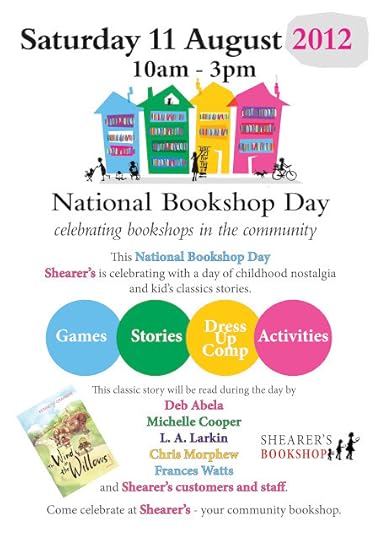

National Bookshop Day 2012

It’s National Bookshop Day this Saturday, the 11th of August, and bookshops across Australia will be celebrating in all sorts of bookish ways. If you’re in Sydney, come along to Shearer’s Bookshop in Norton Street, Leichhardt, where they’ll be celebrating classic children’s literature with games, storytelling and a ‘Dress As Your Favourite Classic Children’s Literature Character’ competition. I’ll be there from 11am, reading and signing books, so come and say hello! (I will probably be dressed as Michelle Cooper, rather than a Classic Character, so I should be easy to recognise.)

August 1, 2012

Vintage Classics Book Giveaway Winners

Thank you so much to everyone who let us know their favourite film and TV adaptations of beloved books. Game of Thrones was very popular, although there were also many fans of various adaptations of the works of Elizabeth Gaskell, L. M. Montgomery and Jane Austen. I have never actually read any of Elizabeth Gaskell’s books, so I’ve added her name to the front of my book journal, along with Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, even though I suspect that book’s going to make me cry. Valerie also asked about a Montmaray mini-series, which I think would be an excellent idea. However, although there’s been some interest, no-one has actually bought the film and TV rights yet, so we can keep producing our own versions in our heads, casting our own personal favourite actors and actresses.

Thank you so much to everyone who let us know their favourite film and TV adaptations of beloved books. Game of Thrones was very popular, although there were also many fans of various adaptations of the works of Elizabeth Gaskell, L. M. Montgomery and Jane Austen. I have never actually read any of Elizabeth Gaskell’s books, so I’ve added her name to the front of my book journal, along with Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro, even though I suspect that book’s going to make me cry. Valerie also asked about a Montmaray mini-series, which I think would be an excellent idea. However, although there’s been some interest, no-one has actually bought the film and TV rights yet, so we can keep producing our own versions in our heads, casting our own personal favourite actors and actresses.

There were so many entries in the book giveaway that I’ve decided to choose five winners, rather than three. Congratulations to Jill, Karen K, Margaret Mayfield, Tara N and Kitty, who have each won a copy of the Vintage Classics edition of A Brief History of Montmaray. The book went on sale in Australia today, alongside lovely new editions of Little Women, I Capture the Castle, The Secret Garden, Swallows and Amazons, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and fourteen other classic children’s novels. Random House Australia is offering Australian readers a chance to win an entire library of Vintage Children’s Classics and is giving away, for a limited time, special gift packs to those who buy three Vintage Children’s Classics. Sorry, all that exciting stuff is for Australians only – but everyone else, keep an eye on this blog for an announcement about another Montmaray giveaway.

July 28, 2012

Miscellaneous Memoranda

Fluffy indicates the time of the crime, while his assistants, Muffin and Smokey, examine the evidence carefully for further clues

- I think I’m writing the wrong sort of books. Apparently, cat mysteries, a “subgenre of detective novels in which crimes are solved either by cats or through feline assistance” are selling “millions upon millions of copies”. I tend to agree with the author of the article, who suggests cats are “more likely to commit crimes than to detect them”. (To appease any cat fanciers who may be reading this, here’s a cat comic.)- Those who regularly use Wikipedia may be interested in this article, which points out that only nine percent of Wikipedia editors are women and that male editors frequently try to delete articles seen as not culturally “significant” enough (that is, too “girly”). This leads, for example, to an article on Kate Middleton’s wedding dress being flagged for deletion for being a “trivial” topic – although somehow, Wikipedia manages to find the space to include more than a hundred articles on Linux.

- I love What Was That Book?, a community on LiveJournal in which readers write in to ask for help finding books they’ve read so long ago that they’ve forgotten the titles and authors. I’m constantly amazed at how quickly the community is able to identify a book, based on very vague clues. For example:

“The last radish in the world (galaxy? universe?) goes up for auction. The person who wins the radish is underwhelmed by the experience of eating the legendary vegetable. It might be a science fiction short story or a scene in a novel.”

And, within twenty-four hours, a reader had let us know that the book was Beauty by Sheri S. Tepper.

- Kill Your Darlings is hosting a YA Championship, in which their “ten favourite YA fanatics – authors, buyers, publishers, readers, writers – [will] champion their favourite Australian YA book from the last 30 years”. The public will then vote on the selected shortlist, although there’s also a People’s Choice category allowing the public to nominate their own favourite books, with book packs as prizes.

- And my own Vintage Classics book giveaway is still on, with entries closing on Wednesday.

July 18, 2012

My Book Journal

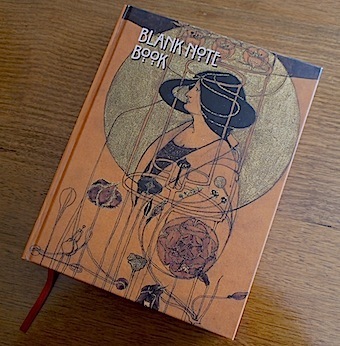

A few years ago, I stopped working at a Proper Job* and on my final day, my colleagues had a little party and presented me with a farewell gift – a lovely silver pen and a blank journal. I’d just had my first novel accepted for publication and my colleagues said I could use the pen and book to write my next novel. It was a lovely idea, and in fact, I did use the pen to take notes for A Brief History of Montmaray (and indeed, I still use that pen nearly every day, because it really is a very nice pen, of exactly the right size and weight and ink colour to suit my tastes). But as for the blank journal – well, I type my novels on a computer, and when I take research notes, they’re scribbled on cheap lecture pads and technicoloured Post-It notes. I couldn’t imagine writing a novel (with all the crossing-out and page-tearing-out that that involves) in a beautiful journal with gilt-edged pages, decorated with a detail from a Charles Rennie Mackintosh painting**.

The book was simply too pretty to sully with my scribblings, so it sat in a cupboard for a couple of years.

However, at the start of 2011, I decided it would be handy to keep a record of all the books I read and to make brief notes on the books I found interesting (either interestingly good or interestingly bad). I suppose I could have just joined Goodreads or LibraryThing, as everyone else does, but I wanted to keep my notes private. I considered setting up some sort of spreadsheet on my computer, but that sounded too much like hard work. And then I remembered my ‘Blank Note Book’.

Readers, it is blank no more.

Note: Photo is artfully blurred so you can’t see what I wrote about Insignificant Others and Dead Until Dark – although I did enjoy both those books, for different reasons.

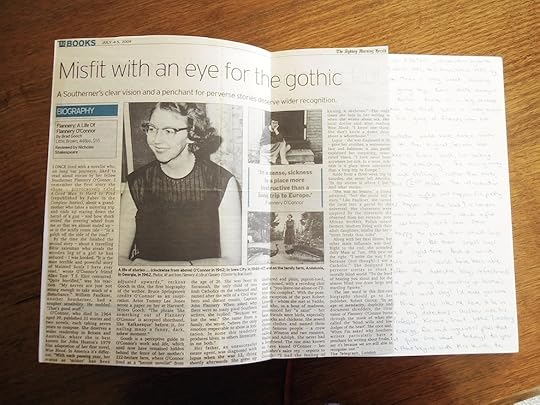

I write down the title and author of each book I read and what I thought of the book. Sometimes I only write a sentence; sometimes I write pages. I often write about the book’s structure and the effectiveness of the literary devices used, because analysing other books helps me to become a better writer. But just as often, my book journal reflects how I was feeling and what was going on in my world at the time I read the book, so I guess it is a bit like a personal diary. The books I really loved get a star, and I use the stars to compile my Favourite Books blog post at the end of each year. Sometimes I also stick in the review that prompted me to try the book in the first place.

At the front of my journal, I keep clippings of book reviews and Post-It notes of titles that have caught my attention. When I start to run out of books to read, I consult these notes and reviews, and track the books down at the library or the bookstore (usually the library, because I am now an impoverished writer lacking a Proper Job). My current To Be Tracked Down book list includes:

The Uninvited Guests by Sadie Jones

A Few Right Thinking Men by Sulari Gentill

Cold Light, the final book in the Edith Campbell Berry trilogy, by Frank Moorehouse

Backwater War by Peggy Woodford

Lettie Fox by Christina Stead

A Pattern of Islands by Arthur Grimble

There are also quite a few books on my list that have not been treated to very much investigation at all. For example, I have a Post-It note that says ‘Hilary McKay – Casson family?’, which means I haven’t actually got around to looking up the book titles, let alone reserving them from the library. I also got stuck on Patrick Melrose’s novels, because the library catalogue informed me it only had the fourth book in a five-book series. (Does anyone know if I need to read Never Mind/Bad News/Some Hope before Mother’s Milk? Or are the books so depressing that I’ll regret reading any of them?) Still, it’s not as though I have a dearth of reading material at the moment.

Now that I’ve started a book journal, I wish I’d kept a record of all the books I’d ever read. It would be fascinating to see what I thought of The Famous Five and Trixie Belden and What Katy Did and all those other books I loved to pieces (literally) in my early reading years. Or maybe it would just be really embarrassing.

* That is, a job which involved me commuting by train to an office, often while wearing a suit, and having someone else pay me each fortnight and even pay me when I went on holiday or got sick . . . Oh, those were the good old days.

** It’s a detail from Part Seen, Imagined Part (1896), which apparently can be viewed at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

*** One day I will figure out how to do proper footnotes in WordPress.

For those of you who keep book journals, I’d also like to remind you that my book giveaway is still open, till the end of the month. You could win a copy of the Vintage Classics edition of A Brief History of Montmaray and then write about it in your journal! (Note: Those who don’t have book journals are also welcome to enter the giveaway.)