Michelle Cooper's Blog, page 33

December 3, 2011

Miscellaneous Memoranda

- Those beautiful, elaborate paper sculptures that have been popping up in Edinburgh libraries seem to have come to an end. Thank you, Mysterious Sculptor.

- Which reminds me of my favourite entry in this year's Creative Reading Prize in the Inkys – the amazing book sculpture (I'm not sure how else to describe it) of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. Look at wee Harry, climbing through the tunnel with his broom, and Slytherin's locket, and the detailed blurb on the back cover! Fabulous work, Rebecca. (And yes, my favourite entry last year was the French-knitted Harry Potter.)

- I love this: Lies I've Told My 3 Year Old Recently. Except the fourth one isn't actually a lie. Tiny bears DO live in drain pipes.

- The FitzOsbornes don't live in a drain pipe, but they are on the Kirkus Reviews Best Teen Books of 2011 list. However, in the interests of balance and to stop myself getting a big head, I should point out that not everyone liked The FitzOsbornes in Exile. This Goodreads reviewer, for example, who said:

"The book was very unrealistic. First off, the reactions to certain situation were very unnaturally calm and anyone had real emotion to any situation. The story wasn't bad but it shouldn't have been that long for such a plot that wasn't that interesting. Overall, the book left me with a very empty feeling. Nothing was settled. You never found out what happened to everyone. I wouldn't recommend this book to anyone."

So, if you haven't read any of my books: you've been warned.

- But if that warning doesn't put you off, you still have time to enter my Montmaray book giveaway. Entries close on the 4th of December (which is actually the 5th of December for Australians).

November 22, 2011

Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons

I knew I was going to get along with Miss Flora Poste, the narrator of this novel, from the very first chapter, in which she explains that her "idea of hell is a very large party in a cold room, where everybody has to play hockey properly". Flora also likes everything about her to be "tidy and pleasant and comfortable". She is therefore presented with quite a challenge when she goes off to live with her relatives at Cold Comfort Farm, following the (unlamented) deaths of her parents.

I knew I was going to get along with Miss Flora Poste, the narrator of this novel, from the very first chapter, in which she explains that her "idea of hell is a very large party in a cold room, where everybody has to play hockey properly". Flora also likes everything about her to be "tidy and pleasant and comfortable". She is therefore presented with quite a challenge when she goes off to live with her relatives at Cold Comfort Farm, following the (unlamented) deaths of her parents.

The Starkadders have always lived at Cold Comfort Farm, even though the place is apparently cursed. The family is ruled over by mad Aunt Ada Doom, who conveniently "saw something nasty in the woodshed" as a child and so must have her every wish fulfilled, for fear she might go even madder. Her daughter Judith is sunk in gloom; Judith's husband Amos spends all his time preaching hellfire at the Church of the Quivering Brethren; their inarticulate elder son Reuben tries to keep the farm going and obsesses about how many feathers his chickens have lost; Seth lounges about with his shirt unbuttoned to the waist, seducing the housemaids; and young Elfine writes terrible poetry and communes with Nature. Then there's their ancient farmhand, Adam Lambsbreath, and his beloved cows (called Graceless, Pointless, Feckless and Aimless); Mrs Beetle the housekeeper and her "jazz quartet" of tiny, illegitimate grandchildren; and a confusion of dirt-encrusted Starkadder cousins, with names like Urk and Micah, who are constantly stealing one another's wives and pushing each other down the well.

Fortunately, Flora enjoys a challenge and she cheerfully sets about improving the lives of all her relatives, whether they like it or not.

This is one of the funniest novels I have ever read. Stella Gibbons pokes fun at everyone and everything: Serious Literature, romance, evangelists, psychoanalysis, intellectuals, people who worship Nature, fashionable Society, the British aristocracy. As Rachel Cooke writes, "Gibbons was a sworn enemy of the flatulent, the pompous and the excessively sentimental." The really clever thing, though, is how Gibbons manages to create over-the-top characters who are nevertheless completely recognisable. Mr Mybug, for example, who is convinced Branwell Brontë wrote Wuthering Heights:

"You see, it's obvious that it's his book and not Emily's. No woman could have written that. It's male stuff . . . There isn't an intelligent person in Europe today who really believes Emily wrote the Heights."

He sounds like V. S. Naipaul.

Although Cold Comfort Farm was first published in 1932, it is supposed to be set "in the near future", sometime after the "Anglo-Nicaraguan wars of '46″. Mayfair is now part of the slums of London, while Lambeth is a fashionable, expensive part of the city. The British railways have fallen into "idle and repining repair" because so many people travel in their own private aeroplanes, and telephones come equipped with a "television dial". Some of this is quite prophetic, but it reads oddly in a novel that otherwise seems thoroughly part of the 1930s. (The excellent 1996 film version of the book wisely omitted these modernistic bits.) One extra note: make sure you read the author's foreword before you read the novel. I didn't, so I missed out on a running joke about literary criticism.

Stella Gibbons wrote two sequels to this book, Christmas at Cold Comfort Farm and Conference at Cold Comfort Farm, which unfortunately, I haven't read. After being out of print for years, they have been republished this year by Vintage Classics, along with a dozen other novels from this author. I am particularly interested in reading Westwood, which is set during the Second World War and sounds fascinating.

More favourite 1930s/1940s British novels:

1. The Cazalet Chronicles by Elizabeth Jane Howard

2. The Charioteer by Mary Renault

3. The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault

4. Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford

Oh, and don't forget that my book giveaway is still on, until the 4th of December. Go and check out the excellent book recommendations from readers, and add a recommendation of your own!

November 13, 2011

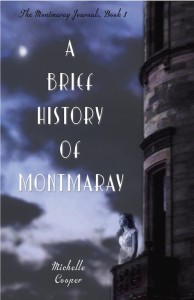

A Brief History of Montmaray Book Giveaway

The Australian and North American publication dates for The FitzOsbornes at War have been announced, so to celebrate, I'm giving away some audiobooks and signed paperbacks of the first book in the series, A Brief History of Montmaray. I realise that most regular readers of this blog have already read it – but perhaps you borrowed it from the library and would like your very own signed copy? Perhaps you have a long car trip planned for the upcoming holidays, and would love to spend eight and a half hours listening to the book being read by Emma Bering? (And she does a brilliant job of reading it with all the different voices and accents, I must say.) Or perhaps you'd like to pass the book or audiobook on to a friend? Of course, people who aren't regular readers of this blog are very welcome to enter, too.

The Australian and North American publication dates for The FitzOsbornes at War have been announced, so to celebrate, I'm giving away some audiobooks and signed paperbacks of the first book in the series, A Brief History of Montmaray. I realise that most regular readers of this blog have already read it – but perhaps you borrowed it from the library and would like your very own signed copy? Perhaps you have a long car trip planned for the upcoming holidays, and would love to spend eight and a half hours listening to the book being read by Emma Bering? (And she does a brilliant job of reading it with all the different voices and accents, I must say.) Or perhaps you'd like to pass the book or audiobook on to a friend? Of course, people who aren't regular readers of this blog are very welcome to enter, too.

If you're one of the three winners, you can choose either a signed copy of the North American paperback edition (pictured above) or the North American audiobook (on seven compact discs). All you need to do is leave a comment below, telling us the title of a book that you've enjoyed and would recommend to other readers.

Here are the conditions of entry:

1. You can talk about any kind of book you've enjoyed – young adult, children's, fiction, non-fiction. There are no wrong answers! Just write a line or two (or more, if you'd like) saying why you recommend the book to other readers.

2. This is an international giveaway. Anyone can enter.

3. Make sure the e-mail address you enter on the comment form is a valid one, so I can contact you if you win (no one will be able to see your e-mail address except me, and I won't show it to anyone else). Please don't include your real residential or postal address anywhere in the comment.

4. The three winners will be chosen at random, unless there are three or fewer comments – in which case, it won't be random and all will have prizes.

5. Entries close on the 4th of December, 2011. The winners will be e-mailed then, and I will send off the winners' books or audiobooks as soon as possible after that.

November 3, 2011

The FitzOsbornes At War

The publication date for the Australian edition of The Montmaray Journals, Book Three: The FitzOsbornes at War is:

2 April, 2012

Give or take a week or so. I mean, we're not talking a Harry Potter-style release date here, with security guards monitoring the cartons of books, and an electronic billboard doing a countdown, and thousands of costumed fans lined up outside bookstores at midnight. (Although, if you want to dress up in a 1940s frock and take your Portuguese Water Dog on a leash when you buy your copy, you can, of course! And please send me a photograph.)

I don't yet know when the North American edition of the book comes out, but I'll tell you as soon as I find out.

November 2, 2011

That GayYA Thing

A month or so ago, while I was locked in my Editing Bunker, there was a bit of a kerfuffle in the blogosphere about the lack of gay (and lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer) characters in books for teenagers. It started off as an argument about whether a particular literary agent had asked two particular authors to remove a gay character from their book, and turned into a wider debate about the experiences of LGBTQ authors and the success (or otherwise) of Young Adult books featuring LGBTQ characters. For those who missed it, there's an excellent summary and discussion at cleolinda's livejournal. During the debate, Malinda Lo, a YA author, gathered some data, constructed some graphs and concluded that "less than 1% of YA novels have LGBT characters".

So: books, teenagers, gayness and maths. How could I possibly resist adding my opinions, even if I am rather late to the discussion? So, here are some of my random thoughts on the GayYA thing:

All of my YA novels contain gay characters. I've never had a literary agent or publisher ask me to de-gay my writing. If they had, I'd have gone looking for another agent and/or publisher. I can honestly say that I've experienced FAR less homophobia in the YA publishing industry than in my previous career as a speech and language pathologist.

That's not to say that things in YA Book World are perfect, and I was saddened to read the accounts of YA authors who had experienced discrimination when trying to get their LGBTQ stories published. I'm also wondering how much of this debate is specific to the United States, which (I think) is a more overtly religious society than Australia. The only homophobic comments I've seen about my Montmaray books have come from United States readers (one of them was even a youth librarian – how depressing). I know David Levithan would disagree (he made a speech* here a few years back, complaining about how backwards Australia was compared to the United States, regarding attitudes to gayness), but I actually think Australians are more tolerant. Or possibly more apathetic. At least we don't have crazy book bannings just about every week.

In addition, I'm sad to say I have to agree with Sarah Rees Brennan's comment about YA books being less likely to be bestsellers if they contain LGBTQ characters. As she points out, books are more likely to sell well if they get a huge push from their publishers, and publishers tend to put a huge amount of effort behind books only if a) the authors are popular already, or b) they think the book is likely to appeal to (that is, not put off) lots of readers. On the other hand, the reasons a book becomes a bestseller are often complicated and mysterious. Certainly, my books don't sell very well, but I doubt that has much to do with the gay characters. It's far more likely to be due to the girls in my books being more interested in giving speeches at the League of Nations than swooning over hot male vampires/werewolves/fallen angels.

I'm also dubious about the "less than 1%" statement by Malinda Lo. Her definition of an 'LGBTQ YA book' was fairly broad – she counted any YA book "published by a traditional publisher that includes a main character or secondary character that is lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning; or a story line related to LGBTQ themes." Even so, her list seemed to have some obvious omissions, some of which were pointed out by commenters on her blog post. (Also, why isn't The FitzOsbornes in Exile on her list? It was published in the US by a traditional publisher; it has gay and bisexual characters; it's even been nominated for next year's American Library Association's Rainbow Books list. Is Toby not gay enough? Is Simon not bisexual enough?) In fairness to Malinda Lo, she acknowledges her list may be incomplete. And she does note that "even if I double the number of titles on the list, the total percentage of LGBTQ YA will still only be approximately 1% of all YA books". Which is very low. Although this percentage will probably come as a relief to those Montmaray reviewers who complained about Toby's gayness – they inevitably went on to bemoan the 'fact' that every second YA book nowadays contains disgusting homosexuals.

I think it's good for LGBTQ teenagers to be able to read YA books about their lives. It's even better if straight teenagers can read about LGTBQ lives, because that might help to decrease homophobic bullying in schools. But I also know that teenagers often read books that are (gasp!) published for adults. This is especially true for books involving LGBTQ issues (ugh, the 'issues' word), because until recently, a lot of those books were published as adult, not YA, in Australia, even when the protagonists were teenagers or young adults. This applied to books by Australian authors (for example, Loaded by Christos Tsiolkas and Sushi Central by Alasdair Duncan) and international authors (for example, Oranges are Not the Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson and The Mysteries of Pittsburgh by Michael Chabon).

All of this made me think about my favourite books about LGBTQ teenagers and young adults, so here are a few of them:

Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You (2007) by Peter Cameron

Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You (2007) by Peter Cameron

I love this book – it's so funny and sad and wise and wonderful. I wish I could have read it when I was a teenager, because oh, how I would have related to awkward, alienated James. The novel isn't really about being a gay teenager, any more than it's about surviving the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York, although both of these are part of the story. As the starred review in Kirkus said, "Cameron's power is his ability to distill a particular world and social experience with great specificity while still allowing the reader to access the deep well of our shared humanity".

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (1985) by Jeanette Winterson

A semi-autobiographical novel about a girl adopted into a Pentecostal family in a mill town in the north of England. Teenage Jeanette is forced to give up her family, her church and her community after she falls in love with another girl. It's not as grim as it sounds – there's plenty of humour and originality alongside the rage and heartbreak. What I really liked about this novel, apart from the inventiveness of the writing, is that it doesn't pretend that being different is easy. It was also made into a brilliant BBC television series.

The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (1988) by Michael Chabon

About the bisexual son of a Jewish gangster, who spends the summer after his college graduation getting entangled with a charming, sophisticated gay man and his self-destructive friend. I'm not sure if this counts as YA (the narrator is in his early twenties, and it contains explicit – though not gratuitous – sex), but it's the sort of book that will really appeal to some older teenagers, and the writing is terrific.

Will Grayson, Will Grayson (2010) by John Green and David Levithan

Mostly about a very large and very gay football player called Tiny Cooper, who writes a musical about himself, his many loves and his friends. It made me laugh and cry.

About a Girl (2010) by Joanne Horniman

About a Girl (2010) by Joanne Horniman

I can't write about this book, because it would be weird and awkward if the author, who is on my blogroll, read it. But I agree with this review.

Rubyfruit Jungle (1973) by Rita Mae Brown

I can't claim this is a Great Work of Literature, but it's lots of fun. Molly, a feisty beauty from a poor Southern family, fights her way into college, then gets expelled after the authorities discover she's in a lesbian relationship with her roommate. She then goes to New York to seek her fortune and have many adventures.

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) by Hanif Kureishi

Okay, this was a film first, but the script was published (with an autobiographical essay titled The Rainbow Sign), so I'm counting it as a YA book. It's about Omar, a gay Pakistani teenager who opens a laundrette in London during the Thatcher years, and his lover is a former skinhead, and Omar's uncle is a drug dealer, and it's really funny and gritty and wonderful.

More LGBTQ YA reading:

Daisy Porter's LGBTQ book reviews at QueerYA

Lee Wind's LGBTQ book reviews, plus discussion of LGBTQ issues, at I'm Here. I'm Queer. What The Hell Do I Read?

Christine A. Jenkins' bibliography of YA books with Gay/Lesbian content, 1969-2009

Malinda Lo's list of LGBTQ books, 2009-2011 (scroll down to the end of her post for the link to a downloadable pdf)

Alex Sanchez's list of Gay Teen Books

The American Library Association's Rainbow Books lists for 2008-2011

William E. Elderton's annotated lists of gay and lesbian books for teenagers. It hasn't been updated recently, but contains lots of Australian and New Zealand authors.

* The only link I can find to the podcast of David Levithan's speech is here (scroll down to the first comment for the link).

October 24, 2011

Love In A Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford

I love this book. It's a masterpiece of social comedy and it deserves to be more widely read, so that's why I've decided to rave about it today. Imagine Pride and Prejudice set in the 1930s, and you'll have some idea of the plot. Not that it's really about the plot – which, for the record, involves posh English girls attempting to find suitable husbands. The real joy of this novel lies in the characters, particularly Lady Montdore, the wildly ambitious mother of beautiful Polly, who is 'destined for an exceptional marriage'. Lady Montdore is a monster – self-centred, snobbish, bossy, greedy, completely deluded as to her value in the world – but she's a very entertaining monster. She provides the author with numerous opportunities to send up the English aristocracy, as in this scene, when Lady Montdore berates our poor narrator, Fanny, the wife of a professor:

I love this book. It's a masterpiece of social comedy and it deserves to be more widely read, so that's why I've decided to rave about it today. Imagine Pride and Prejudice set in the 1930s, and you'll have some idea of the plot. Not that it's really about the plot – which, for the record, involves posh English girls attempting to find suitable husbands. The real joy of this novel lies in the characters, particularly Lady Montdore, the wildly ambitious mother of beautiful Polly, who is 'destined for an exceptional marriage'. Lady Montdore is a monster – self-centred, snobbish, bossy, greedy, completely deluded as to her value in the world – but she's a very entertaining monster. She provides the author with numerous opportunities to send up the English aristocracy, as in this scene, when Lady Montdore berates our poor narrator, Fanny, the wife of a professor:

"'You know, Fanny,' she went on, 'it's all very well for funny little people like you to read books the whole time, you only have yourselves to consider, whereas Montdore and I are public servants in a way, we have something to live up to, tradition and so on, duties to perform, you know, it's a very different matter . . . It's a hard life, make no mistake about that, hard and tiring, but occasionally we have our reward – when people get a chance to show how they worship us, for instance, when we came back from India and the dear villagers pulled our motor car up the drive. Really touching! Now all you intellectual people never have moments like that.'"

Of course, things don't go to plan, and Polly rebels in a manner calculated to drive her mother mad. This sets the scene for the introduction of another wonderful character, Cedric, the heir to the Montdore fortune. It was unusual enough in 1949 (the year the book was first published) for a novel to mention homosexuality, but it was revolutionary to have a happy and openly gay character who charms nearly everyone he meets. He even manages to dazzle the Boreleys, a family notorious for its intolerance:

"'Well, so then Norma was full of you, just now, when I met her out shopping, because it seems you travelled down from London with her brother Jock yesterday, and now he can literally think of nothing else.'

'Oh, how exciting. How did he know it was me?'

'Lots of ways. The goggles, the piping, your name on your luggage. There is nothing anonymous about you, Cedric . . . He says you gave him hypnotic stares through your glasses.'

'The thing is, he did have rather a pretty tweed on.'

'And then, apparently, you made him get your suitcase off the rack at Oxford, saying you are not allowed to lift heavy things.'

'No, and nor am I. It was very heavy, not a sign of a porter as usual, I might have hurt myself. Anyway, it was all right because he terribly sweetly got it down for me.'

'Yes, and now he's simply furious that he did. He says you hypnotised him.'

'Oh, poor him, I do so know the feeling.'"

Then there are Fanny's eccentric relatives – her wild Uncle Matthew, vague Aunt Sadie, hypochondriacal stepfather Davey, and exuberant little Radlett cousins – with many of these characters inspired by Nancy Mitford's real family. In addition, the author provides a wickedly funny look at English politics, fashion, marriage and child rearing.

[image error]Love in a Cold Climate is actually the second book narrated by Fanny. The first, The Pursuit of Love, was published in 1945. I hesitate to call it a prequel, because that would suggest you need to read it first, and I don't think you do. It stretches over a longer time period, and is mostly the story of Fanny's cousin and best friend, Linda (Lady Montdore, Polly and Cedric don't make an appearance in this one, unfortunately). Some readers prefer this first book to the second, but I think it really depends on whether you regard Linda as a tragic romantic heroine or a spoiled, self-centred brat. As you've probably guessed, I'm in the latter camp (I really can't forgive Linda's treatment of her hapless daughter). I also think this book ends too abruptly – as though the author suddenly got tired of typing. However, there's a lot of enjoyment in the descriptions of the Radlett family, so if you adore Love in a Cold Climate, you'll probably like The Pursuit of Love as well. There's also a BBC television series based on both books, but I haven't seen it (and it doesn't appear to be available in Australia).

I've previously written about one of Nancy Mitford's earlier novels, Wigs on the Green (1935), which is interesting for historical and political reasons, but doesn't have much literary merit. I cannot recommend The Blessing (1951) at all, because it's awful. However, it and Don't Tell Alfred (1960) have recently been re-released with lovely illustrated covers.

[image error]I can recommend Noblesse Oblige: An Enquiry into the Identifiable Characteristics of the English Aristocracy, a biased but very entertaining collection of essays and cartoons about 'Upper-Class English Usage', edited by Nancy Mitford and including contributions from Evelyn Waugh and John Betjeman. Laura Thompson has also written a biography of Nancy Mitford called Life in a Cold Climate, which discusses all her books and the influences for her novels.

More favourite 1930s/1940s British novels:

1. The Cazalet Chronicles by Elizabeth Jane Howard

2. The Charioteer by Mary Renault

3. The Friendly Young Ladies by Mary Renault

October 16, 2011

Finished! Sort of . . .

I have finally finished the structural edit of The FitzOsbornes at War, and have sent it off to my publishers, and now I feel like this:

'Jove Decadent' (1899) by Ramon Casas

(Except I'm not really feeling decadent, just exhausted.)

For those who aren't sure what a structural edit is, the nice people at Alien Onion have provided a helpful explanation here. In the case of The FitzOsbornes at War, my editors (two of them, one in Australia and one in the United States) sent me a long letter full of questions and suggestions, such as:

Could you explain in more detail about Toby's plan to do [mysterious thing]?

and

It would be good if there was a scene that actually showed Sophie doing [important thing], instead of her merely talking about it, three months later.

and

It's great that Toby tells Sophie all about [shockingly awful thing], but how come she never mentions it in her journal ever again?

and

It would be nice if that Big Declaration of Love scene was even more romantic and soppy.

And, because my editors are very efficient, they also pointed out some smaller issues that usually fall into the area of copy-editing. For example, Toby's birthday suddenly moved from March to February, and Sophie's favourite dress became mysteriously longer over the course of a year. Oops! All fixed now.

The manuscript now goes off to the copy-editors, who will pore over it with their magnifying glasses and identify all my narrative inconsistencies, historical errors and convoluted sentences, so that I can fix those, too. Then the whole thing goes off to the typesetters, who print out proofs, which are then proof-read by everyone, including me. So, as you can see, the book is practically done!

I've also had a look at three potential covers for the Australian paperback edition of The FitzOsbornes at War. They are all beautiful, and I have sent off my feedback on each one. I thought the first was a tiny bit too modern, the second was a little too similar to the first two Montmaray Journals books, but the third was just right. Well, with a few tiny tweaks . . . Anyway, we shall see.

I've also just heard back from my American editor, who has already read the revised final chapter of the new draft and it made her cry! (Because it was so emotionally-involving and heart-rending, not because the writing was so bad that she regretted having ever signed up the book in the first place.) Yes! My job is done!

October 10, 2011

Anatomy Of A Novel: A Brief History of Montmaray

The Alecton attempts to capture a giant squid off Tenerife in 1861. Illustration from Harper Lee's 'Sea Monsters Unmasked', London, 1884.

Simmone Howell has very kindly invited me to be part of her Anatomy of a Novel series, in which "authors (mostly Australian, mostly YA) dissect their own books for your delight". It's a really fascinating set of blog posts, by authors such as Melina Marchetta, Michael Pryor, Kirsty Murray and many more. I've written about the fictional and real-life inspirations for A Brief History of Montmaray here (and yes, one of those inspirations may possibly be the Giant Squid).At the moment, I'm still stuck in my Editing Bunker, but I hope to emerge next week with some new blog posts.

September 16, 2011

Broccoli: It's Good For You!

Is it possible to learn about history through fiction? Or should historical facts only be acquired via proper, serious non-fiction books which have footnotes and sepia photographs and extensive bibliographies? Christchurch City Libraries Blog has a thoughtful post about the issue, inspired partly by The FitzOsbornes in Exile. The blogger notes that I have sneakily inserted quite a few historical facts into the novel:

Broccoli! It's good for you! Even though it isn't quite as delicious as chocolate!

"A bit like parents who sneak broccoli into chocolate cake, the Montmaray books are full of historical detail, actual real stuff that happened. I am learning, not only about things like the War of the Stray Dog, but also the Spanish Civil War, British court etiquette, and the often murky political allegiances of upper-class English people between the wars."

This is all quite true. I confess. I love broccoli, in both its literal and metaphorical forms. The FitzOsbornes in Exile is stuffed so full of broccoli that it's only thanks to my wonderful editors that the whole thing doesn't taste and look exactly like vegetable terrine. I'm struggling through the same issue at the moment, as I edit The FitzOsbornes at War, the final Montmaray novel. It is a very, very long manuscript, which I'd like to make a bit shorter, and it would be logical to remove some of the information about wartime events outside England. The problem is that I find all that background information absolutely fascinating. I have to keep reminding myself that I am not writing a textbook about the Second World War, but a story, and that if the factual information does not have a direct bearing on my fictional characters, then it doesn't belong in the novel. It doesn't matter if I spent an entire fortnight researching a particular event – if those historical facts can't be blended in smoothly, they have no place in my chocolate cake (admittedly, a cake made of very bittersweet, dark chocolate). As New Zealand author Rachael King points out,

"When you're reading my book, I don't want you to be thinking about me and my research. If you are, I've failed in my job."

And apparently she knows how to skin a tiger, so I think we should all pay careful attention to what she has to say.

August 26, 2011

Girls and Boys and Books, Yet Again

Oh, no! The YA publishing industry is dominated by girls! Girls reading books, girls writing books, girls actually allowed to be main characters in books . . . It's out of control and it has to stop, says Robert Lipsyte in his recent New York Times essay, Boys and Reading: Is There Any Hope?

Fortunately for all of us, Aja Romano has now published a brilliant response to this rubbish. Unlike Mr Lipsyte's essay, Ms Romano's article is full of facts and logic and common sense, and is written by someone who's actually familiar with contemporary YA literature. It's well worth a read.