Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 173

July 24, 2020

Empress Matilda’s coronation as Queen of the Romans

The future Empress Matilda was born around February 1102 as the daughter of King Henry I of England and Matilda of Scotland. A younger brother was born the following year. We know very little of Matilda’s early childhood and education. She probably remained with her mother, and she was known to be literate.

By 1108, the future Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, came to her father with a proposal for Matilda. It was a magnificent match, and her dowry was estimated at 10,000 marks in silver. On 17 October 1109, Matilda made her first appearance in a royal council at Nottingham. She witnessed the royal charter creating the see of Ely and added her cross as “sponsa regis Romanorum” – the betrothed wife of the King of the Romans.

In February 1110, envoys arrived to take the young Matilda to her future husband. She was just eight years old and left almost everything she knew behind. She landed at Boulogne and travelled to Liège, where she met Henry for the first time – he was 23 years old at the time. He received her “as befitted a King.” They then moved north to the city of Utrecht for the Easter festivities. Their formal betrothal took place at Utrecht before they moved on down the Rhine to Cologne, Speyer, Worms and finally, Mainz. Mainz was home to one of the three Kaiserdome, imperial churches which were built in red sandstone.

On 25 July 1110, Matilda was crowned Queen of the Romans at Mainz Cathedral, following in the footsteps of Henry’s grandmother Agnes of Poitou who was also crowned there in 1043. It was also the feast of St James the Apostle, whose mummified hand was part of the relics in the royal chapel. As the Archbishopric of Mainz was vacant, she was anointed by Archbishop Frederick of Cologne, and he placed a crown – probably one that was too large for a child – on her head. She was carried by Archbishop of Trier. After her coronation as Queen of the Romans, Matilda was sent away to be prepared for her future role under the guardianship of Bruno of Trier.

In January 1114, before her 12th birthday, she was formally married to Henry at Worms and became known as the Holy Roman Empress, though she was never crowned as such. She was widowed on 23 May 1125, and she would eventually return to England to become – albeit briefly – the Lady of the English.1

Mainz Cathedral

Click to view slideshow.

The post Empress Matilda’s coronation as Queen of the Romans appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 23, 2020

Queen Zhuang Fanji – A Virtuous Lady of Ability

Queen Zhuang Fanji lived during the Spring and Autumn period, an era in which the states of Jin, Qin, Qi, and Chu were breaking away from the ruling Zhou dynasty and forming their own dynasties.[1] She was known to be a virtuous and capable stateswoman.[2] Many historians attributed Fanji with turning her weak kingdom of Chu into a superpower.[3] She has also remained a popular subject in Chinese literature.[4]

Zhuang Fanji was born in 625 B.C. E.[5] Her last name was Ji, and her family came from the Fan region.[6] She married King Zhuang of Chu and became his queen in 611 B.C.E.[7] Throughout her reign as queen, her husband had many concubines. However, Queen Fanji never became jealous of his concubines and always behaved in the proper manner befitting a virtuous wife.[8] She even sought additional concubines for her husband.[9] Under her guidance, the palace remained peaceful.[10]

In the early years of King Zhuang’s reign, he neglected his official duties for leisure activities such as hunting and travelling.[11] Queen Fanji constantly urged him to focus on his kingdom and to govern more efficiently.[12] However, King Zhuang appointed the inefficient Yu Qiuzi to be his prime minister.[13] Queen Fanji urged her husband to replace Yu Qiuzi with a more capable minister.[14] After much persuasion, King Zhuang replaced him with Shu Aosun.[15] Shu Aosun was known for his “morality and ability”.[16] He helped Chu become a flourishing and prominent kingdom.[17]

In 601 B.C.E., King Zhuang died. The next king was Fanji’s son, Xiong Shen. Facts about her later life are unknown.[18] Her tomb resides in Jiangling county. Queen Fanji was known to have been a wise advisor to the king. Through her guidance, she allowed Chu to become one of the top powers in the Spring and Autumn period.[19] Official Chu historians wrote that “Zhuang was able to lord it over others because Fanji made all the effort.”[20] Since then, Fanji has been featured prominently in Chinese literature. Tang prime minister, Zhang Shen, wrote a poem “To Fanji’s Tomb on Climbing Jin Li Tai”.[21] His famous line from the poem alludes to her: “Chu became the lord, Fanji did the work”.[22] Yu Jinfeng, a Qing administrator, wrote on her tomb that the queen was “A Virtuous Lady of Ability.”[23]

References:

Eno, R. (2010). 1.7. Spring and Autumn China (771-453). Indiana University, PDF.

Duncan, John (2015). Creative Women of Korea: the Fifteenth through the Twentieth Centuries. Edited by Young-Key Kim-Renaud, Routledge.

Yunhuang, Luo (2015). Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century. Edited by Barbara Bennett Peterson, Routledge.

[1] Yunhuang p. 23; Eno, p.3

[2] Yunhuang p. 24; Duncan, p. 41

[3]Yunhuang p. 24; Duncan, p. 41

[4] Yunhuang, p. 24

[5] Yunhuang, p. 23

[6] Yunhuang, p. 23

[7] Yunhuang, p. 23

[8] Yunhuang, p. 23

[9] Yunhuang, p. 23; Duncan, p. 40

[10]Yunhuang, p. 23

[11]Yunhuang, p. 23; Duncan, p. 40

[12] Yunhuang, pp. 23-24; Duncan, p. 40

[13]Yunhuang, p. 24; Duncan, p. 40

[14] Yunhuang, p. 24; Duncan, p. 40

[15] Yunhuang, p. 24

[16] Yunhuang, p. 24

[17]Yunhuang, p. 24

[18] Yunhuang, p. 24

[19]Yunhuang, p. 24; Duncan, p. 40

[20] Yunhuang, p.24

[21] Yunhuang, p. 24

[22]Yunhuang, p. 24

[23]Yunhuang, p. 24

The post Queen Zhuang Fanji – A Virtuous Lady of Ability appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 22, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – A third tragedy

With Wilhelmina’s marriage to Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin on 7 February 1901, she and her mother both fervently prayed for healthy children to continue their line. Tragically, Wilhelmina would go on to suffer five miscarriages and only one healthy child was born to Wilhelmina and Henry.

In the spring of 1906, Wilhelmina was pregnant for the third time. Her first pregnancy had ended in a miscarriage at the end of 1901. Her second pregnancy ended in the stillbirth of a son following a bout of typhoid fever in 1902. Wilhelmina kept her pregnancy a secret from anyone outside of the family and only wrote to her former nanny De Kock on 19 July 1906, “My enemies, the papers, have written a lot about me, long before they had a reason for it. I can tell you now, although they are way too early, that the rumour they are spreading is true.”1 On 4 July 1906, Wilhelmina wrote to her mother about the birth of a son to Crown Princess Cecilie of Germany (Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin) and Crown Prince Wilhelm. “Such a happiness for her, her husband, and the Emperor!” Cecilie had given birth just over a year of getting married.

Wilhelmina took to her bed following a garden party, and a “fausse couche”(miscarriage) took place on 23 July. On the 25th, newspapers reported, “A minor disposition of Her Majesty The Queen during some days has thwarted hopes that had been cherished for a while. The condition of Her Majesty does not give cause for concern.”2 Her private secretary reported that Wilhelmina was “very well and even cheerful.”3

Despite her cheerfulness, the pressure must have been getting to her. She had been married for five years and had suffered three losses. The prospect of a German Prince on the throne began to loom.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – A third tragedy appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 21, 2020

Catherine the Great – The later years (Part five)

Catherine saw her son as her rival, and she never gave him a role in government. Despite this, he and his wife were required to appear at official ceremonies. He and his mother had very little contact otherwise. Catherine even began to consider skipping Paul all together and making her eldest grandson Alexander her heir. Paul began to suspect this, and it made their already bad relationship even worse. For now, he could do nothing but wait though he had instructed his wife to secure Catherine’s papers in case she died while he was away.

By the early 1790s, France was close to a revolution, and Catherine feared Europe would follow suit. She issued a memorandum suggesting measures as to how to suppress the revolution and re-establish the monarchy as “The cause of the King of France is the cause of all Kings…”1 In January 1793, King Louis XVI was executed by guillotine and when Catherine was informed, she became physically ill. She ordered the court to go into mourning for six weeks and a total break in relations with France. Six months later, his Queen Marie Antoinette was also guillotine. Fearing that the ideas might cross into Russia, Catherine ordered all bookshops to register their catalogues with the Academy of Sciences, and she ordered the confiscation of a complete edition of Voltaire’s works. Private printing presses were closed, and all books had to be submitted to a censorship office before they could be published.

By now, Catherine also began feeling the years. She had grown heavier, her hair had turned white, and she had dentures. She had also begun to use reading glasses. For years, she suffered from headaches and indigestion. She also began to suffer from rheumatism, and sometimes she had open leg sores.

Nevertheless, she kept going strong. Her favourite summer retreat was Tsarskoe Selo, where she was surrounded by her grandchildren. She had not taken her grandchildren from Maria and Paul as Elizabeth had done with her son, but she had regular contact with them. As a child, Alexander often spent hours playing on the floor next to her. She wrote, “I have said it to you before, and I say it again, I dote on the little monkey… In the afternoon, my little monkey comes as often as he likes and spends three or four hours a day in my room.”2 She also wrote pages of instructions for the education of Alexander and his younger brother Constantine. Her granddaughters were left to their parents choice of education.

She pushed Alexander to marry early, and in 1792, he married Louise of Baden, renamed Elizabeth Alexeievna. They were 15 and 14 years old respectively at the time of their wedding. Unfortunately, their marriage produced only two short-lived daughters. Constantine would not leave any legitimate children (and he also refused the throne in 1825), and so the throne was destined to pass to her third grandson Nicholas, born the year she died.

On 15 November 1796, Catherine appeared in public for the last time. The following morning, she awoke as usual at six, had a cup of black coffee and sat down to write. At nine, she went into her dressing room and did not come out again. Attendants waited and waited, but she did not return. Eventually, they found her unconscious on the floor of the water closet. She was carried into her bedroom, but she was too heavy to lift into bed. A mattress was brought in so that she could lay on it. Her personal physician was called, and he bled her from a vein in her arm. Her eyes remained closed, and she did not talk. Her son was sent for immediately. Paul and Maria arrived in the evening and were greeted by Alexander and Constantine. It was suspected that she had suffered a stroke, and she remained motionless as Paul kissed her hands. They held a vigil for the entire night. In the morning, the doctor told Paul that there was no hope, and he ordered his mother’s papers to be sorted and sealed.

By the late afternoon, Catherine began having trouble breathing. She was administered the last rites, and she died on 17 November 1796 at 9.45 pm without having regained consciousness. Two days later, the new Emperor Paul retrieved the coffin of his father from the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, and it was placed next to Catherine’s for her lying-in-state. They were buried together at the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul.

In 1788, Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm, wrote to her and called her “Catherine the Great.” She replied to him, “I beg you no longer to call me Catherine the Great, because… my name is Catherine II.” After her death, many Russians began calling her Catherine the Great. She had come to Russia as an obscure German Princess; she would be remembered for bringing a Golden Age to Russia.

The post Catherine the Great – The later years (Part five) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 20, 2020

Catherine the Great – Ruling an Empire (Part four)

Catherine enforced her success by rewarding those who helped to put her on the throne, including the church and the army. She also cancelled the unpopular alliance with Prussia but assured them she had no wish for a new war. She also called on Russia’s two most experienced statesmen. She settled into a routine; she received ministers in the morning and drafted decrees, at 11 am, she did her toilette and entertained Orlov, at 1 pm she had lunch and then worked in her apartments until 6 pm. In the evenings, she held court, went to the theatre or held balls. She often worked 15 hour days.

In 1764, the man known as Prisoner Number One, the child Emperor Ivan VI, son of Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna of Russia, was part of a plot to set him free, and he was killed during it. There was now just one clear heir to the throne – Catherine’s son Paul, and he was still a child – Catherine was free to do as she wished.

Russia was revitalised under her reign. Catherine became a patron of the arts – the current Hermitage museum began as her personal collection. She wanted to modernise Russia but faced difficulties as the economy depended on serfdom and serf-labour. She often relied on her favourites, such as Orlov and later Potemkin. She also pioneered the use of inoculation against smallpox in Russia. Both she and Paul were inoculated. She also kept in touch with intellectuals and began a correspondence with Voltaire in 1763. Catherine rejected torture and wrote, “The use of torture is contrary to sound judgement and common sense. Humanity itself cries out against it, and demands it to be utterly abolished.”1 She believed punishments should fit the crime and detailed this and many other ideas in the so-called Nakaz.

In addition to her ideas on inoculation, she also decreed that the capital of every province should have a general hospital and that every country within it should have a physician, a surgeon, two surgical assistants, two apprentices and an apothecary. This still often meant that there was just one physician for many thousands, but before this, these areas had nothing.

From 1774, Catherine was involved with Gregory Potemkin, and he was a powerful figure by her side until his death in 1791. He was not only her lover, but he also became her advisor, governor and viceroy of half of Russia. They may have even been married. Despite this, Catherine also had other lovers, probably around 12 total. They were often young officers, selected by Catherine to “love and be loved.”2

The relationship with her son Paul was never easy. He had been taken from her at birth, and when she ascended the throne, the damage had been done. The question of his paternity hung over him, and when she was proclaimed Empress, she made sure to proclaim him as her heir as he was definitely related to her. The general public knew little of his assumed paternity and over the years as Paul became to resemble Peter, even many of those at court began to believe he was really Peter’s son. Paul believed himself to be Peter’s son and grew up idolising him. He also began to question why his mother was on the throne instead of him. After a severe bout of influenza in 1771, Catherine knew it was time to secure the succession for another generation.

Catherine invited the three unmarried daughters of Louis IX, Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt; Amalie (18), Wilhelmina (17) and Louise (15), to Russia so that Paul could choose between them. They arrived in the spring of 1773, and Paul picked Wilhelmina. In August 1773, Wilhelmina was received in the Russian Orthodox Church as Natalia Alexeievna. They married the following month. Though Catherine initially praised her new daughter-in-law, she was soon irritated with her. She wrote, “There is neither grace, nor prudence, nor wisdom in any of this and God knows what will become of her… Just think that after more than a year and a half, she still doesn’t speak a word of the language.”3

Natalia finally fell pregnant in the fall of 1775, and she went into labour in the early hours of 21 April 1776. Catherine hurried to be by her side. It was to be a long and difficult labour. On the third day, the doctors agreed that there was no possibility of saving the child – it was most likely already dead. On the fourth day, Natalia was given the last rites. At six in the evening of 26 April, Natalia died after five days of agony. Catherine and Paul had stayed with her. The child had been too large to pass through the birth canal; it had been a “perfectly formed boy.”4 Paul was devastated and initially refused to have his wife’s body moved. He did not attend her funeral. Catherine had to find a way to break his grief so that he would marry again. As she had expected, she found letters that Natalia had written to her lover – who was also Paul’s best friend. Paul was enraged and declared himself ready to be married again immediately. Catherine wrote, “I have wasted no time. At once, I put the irons in the fire to make good the loss, and by so doing, I have succeeded in dissipating the deep sorrow that overwhelmed us. The dead being dead, we must think of the living.”5 Of Natalia, she wrote, “Well, since it has been proven that she could not give birth to a living child, we must not think about her anymore.”6

A new bride was found in Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg, later renamed Maria Feodorovna, and they were married later that same year. Just fourteen months later, Maria gave birth to a healthy boy. Catherine finally had her heir, and Maria would give birth to ten children, of which nine survived to adulthood. Despite Paul’s newfound happy family life, he remained frustrated and was left out of the loop. While his mother lived, he would not have any power.

Part five coming soon.

The post Catherine the Great – Ruling an Empire (Part four) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 19, 2020

Catherine the Great – The coup that made her Empress in her own right (Part three)

As Empress Elizabeth’s health deteriorated, Catherine found herself pregnant with Gregory Orlov’s child, and she began to seclude herself. Peter was already talking of repudiating her and Catherine did not want to fuel the fire by appearing in public while pregnant. On 3 January 1762, Empress Elizabeth suffered a massive stroke, and both Peter and Catherine were summoned. There was no hope of recovery. She died on 5 January 1762 and Peter became Emperor Peter III of Russia with Catherine as his Empress.

Elizabeth’s body lay in state at the Kazan Cathedral where Catherine – wearing black – knelt beside the coffin. Catherine knew all too well that this state of apparent humility and devotion would appeal to the people. The French ambassador reported that “more and more, she captures the hearts of Russians.”1 Meanwhile, Peter’s behaviour stood in stark contrast with Catherine’s. He mocked the proceedings in public and spent most of his time drunk in his apartments. He also managed to insult the Russian Orthodox Church almost immediately. The peace treaty with Prussia was signed in early May.

Meanwhile, Catherine waited out her pregnancy. Alexis Gregorovich, later Count Bobrinsky, was born on 22 April 1762. She recovered quickly, and the child was whisked away and placed in the care of the wife of Vasily Shkurin, Catherine’s valet. Now free from the constraints of pregnancy, she could finally act. On 23 June, Peter left for Oranienbaum to drill soldiers before sending them off to war. He instructed Catherine to go to Peterhof to avoid the restlessness of the city, and she went there on 28 June. As a precaution, she left Paul behind and made sure that money and wine were being passed among the soldiers in the barracks. Gregory Orlov won the support of many officers in the Guards and thousands of others.

On 9 July 1762, the time had come. Catherine was taken to the barracks of the Izmailovsky Guards who gathered around her and kissed her hands, feet and the hem of her dress. Catherine proclaimed that her life and that of her son had been threatened by the Emperor and that she was compelled to throw herself on their protection for the sake of her beloved country and their holy Orthodox religion. The regimental chaplain administered an oath of allegiance to “Catherine II of Russia.” She was then escorted to the barracks of the Semyonovsky Guards, who also swore their allegiance. Catherine decided to enter St Petersburg immediately preceded by chaplains, priests and followed by the cheering Guards. She rode to the Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan and stood before the iconostasis (icon screen) while the archbishop of Novgorod proclaimed her Gosudarina (sovereign autocrat). Bells began to ring around the city as Catherine walked from the Cathedral to the Winter Palace. An obstacle arose when the Preobrazhensky Guards wavered, but they decided in her favour and joined her, shouting “Matushka, forgive us for coming last.”2 On the palace balcony, Catherine presented the 8-year-old Paul to the crowd as heir to the throne. Peter remained unaware of all of this.

Catherine proclaimed herself colonel of the Preobrazhensky Guards and dressed in their uniform; she marched to Oranienbaum. As Peter learned of this, he wrote her a letter apologising for his behaviour and offered to share the throne with her. Catherine decided that she would not reply to Peter’s letter. He wrote again, offering to abdicate if he could take his mistress with him to Holstein. Catherine accepted this offer if the abdication came in writing. He did so, and the King of Prussia later commented, “He allowed himself to be dethroned like a child being sent to bed.”3 But she wasn’t about to let Peter slip away to Holstein, and both he and his mistress were captured at Oranienbaum and taken back to Peterhof. Here they were separated, and they never saw each other again. Peter was led upstairs to a room where he surrendered his sword and the blue ribbon of the Order of St. Andrew. He was also stripped of his uniform. He was informed that he was now a state prisoner and would be taken to “decent and convenient rooms” at the Schlüsselburg Fortress. Catherine did not want to see him. On 11 July, Catherine rode back into St. Petersburg in triumph. As his rooms were being prepared at Schlüsselburg Fortress, Peter was sent to Ropsha, and he would not make it to Schlüsselburg. He died there on 17 July 1762 in unclear circumstances.

Catherine had to be seen as blameless, and she treated it as a medical situation. She ordered a postmortem examination, and the doctors declared that they found no evidence of poisoning – thus it must be natural causes. She issued a proclamation that declared his death to be of “hemorrhoidal colic.” His body also lay in state to stay ahead of rumours that he was still hidden away somewhere. Catherine later wrote, “So at last God has brought everything to pass according to His designs. The whole thing is rather a miracle than a pre-arranged plan, for so many lucky circumstances could not have coincided unless God’s hand had been over it all. Hatred of foreigners was the chief factor in the whole affair, and Peter III passed for a foreigner.”4

On 3 October 1762, Catherine was crowned on the diamond throne of Tsar Alexis with the Imperial Crown of Russia.

Part four coming soon.

The post Catherine the Great – The coup that made her Empress in her own right (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 17, 2020

Book News August 2020

Marie Antoinette’s Confidante: The Rise and Fall of the Princesse de Lamballe

Paperback – 30 April 2020 (UK) & 19 August 2020 (US)

Marie Antoinette has always fascinated readers worldwide. Yet perhaps no one knew her better than one of her closest confidantes, Marie Thrse, the Princess de Lamballe. The Princess became superintendent of the Queens household in 1774, and through her relationship with Marie Antoinette, a unique perspective of the lavishness and daily intrigue at Versailles is exposed. Born into the famous House of Savoy in Turin, Italy, Marie Thrse was married at the age of seventeen to the Prince de Lamballe; heir to one of the richest fortunes in France. He transported her to the gold-leafed and glittering chandeliered halls of the Chteau de Versailles, where she soon found herself immersed in the political and sexual scandals that surrounded the royal court. As the plotters and planners of Versailles sought, at all costs, to gain the favour of Louis XVI and his Queen, the Princess de Lamballe was there to witness it all. This book reveals the Princess de Lamballes version of these events and is based on a wide variety of historical sources, helping to capture the waning days and grisly demise of the French monarchy. The story immerses you in a world of titillating sexual rumours, blood-thirsty revolutionaries, and hair-raising escape attempts and is a must read for anyone interested in Marie Antoinette, the origins of the French Revolution, or life in the late 18th Century.

To Free the Romanovs: Royal Kinship and Betrayal in Europe 1917-1919

Paperback – 15 April 2020 (UK) & 1 August 2020 (US)

King George V s role in the withdrawal of an asylum offer was covered up. Britain refused to allow any Grand Dukes to come to England, a fact that is rarely explored.

When Russia erupted into revolution, almost overnight the pampered lifestyle of the Imperial family vanished. Within months many of them were under arrest and they became enemies of the Revolution and the Russian people . All showed great fortitude and courage during adversity. None of them wanted to leave Russia; they expected to be back on their estates soon and to live as before. When it became obvious that this was not going to happen a few managed to flee but others became dependent on their foreign relatives for help.

For those who failed to escape, the questions remain. Why did they fail? What did their relatives do to help them? Were lives sacrificed to save other European thrones? After thirty-five years researching and writing about the Romanovs, Coryne Hall considers the end of the 300-year-old dynasty and the guilt of the royal families in Europe over the Romanovs bloody end. Did the Kaiser do enough? Did George V? When the Tsar s cousins King Haakon of Norway and King Christian of Denmark heard of Nicholas s abdication, what did they do? Unpublished diaries of the Tsar s cousin Grand Duke Dmitri give a new insight to the Romanovs feelings about George V s involvement.

Marie Antoinette’s World: Intrigue, Infidelity, and Adultery in Versailles

Hardcover – 15 June 2020 (US) & 1 August 2020 (UK)

This riveting book explores the little-known intimate life of Marie Antoinette and her milieu in a world filled with intrigue, infidelity, adultery, and sexually transmitted diseases. Will Bashor reveals the intrigue and debauchery of the Bourbon kings from Louis XIII to Louis XV, which were closely intertwined with the expansion of Versailles from a simple hunting lodge to a luxurious and intricately ordered palace. It soon became a retreat for scandalous conspiracies and rendezvous—all hidden from the public eye. When Marie Antoinette arrived, she was quickly drawn into a true viper’s nest, encouraged by her imprudent entourage. Bashor shows that her often thoughtless, fantasy-driven, and notorious antics were inevitable given her family history and the alluring influences that surrounded her. Marie Antoinette’s frivolous and flamboyant lifestyle prompted a torrent of scathing pamphlets, and Bashor scrutinizes the queen’s world to discover what was false, what was possible, and what, although shocking, was most probably true.

Readers will be fascinated by this glimpse behind the decorative screens to learn the secret language of the queen’s fan and explore the dark passageways and staircases of endless intrigue at Versailles.

The Duchess of Windsor: The Uncommon Life of Wallis Simpson

Paperback – 25 August 2020 (US & UK)

It was the love story of the century–the king and the commoner. In December 1936, King Edward VII abdicated the throne to marry “the woman I love,” Wallis Warfield Simpson, a twice-divorced American who quickly became one of the twentieth century’s most famous personalities, a figure of intrigue and mystery, both admired and reviled.

Grace: A Biography

Paperback – 18 August 2020 (US & UK)

This comprehensive biography draws from previously unreleased documents from the Grimaldi family archive and, for the first time, access to the letters between Kelly and Hitchcock. It is also based on interviews with Kelly’s companions and relatives, including an exclusive interview with Prince Albert II of Monaco.

Finding Freedom: Harry and Meghan and the Making of a Modern Royal Family

Paperback – 11 August 2020 (US & UK)

When news of the budding romance between a beloved English prince and an American actress broke, it captured the world’s attention and sparked an international media frenzy. But while the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have continued to make headlines—from their engagement, wedding, and birth of their son Archie to their unprecedented decision to step back from their royal lives—few know the true story of Harry and Meghan.

For the very first time, Finding Freedom goes beyond the headlines to reveal unknown details of Harry and Meghan’s life together, dispelling the many rumors and misconceptions that plague the couple on both sides of the pond. As members of the select group of reporters that cover the British Royal Family and their engagements, Omid Scobie and Carolyn Durand have witnessed the young couple’s lives as few outsiders can.

With unique access and written with the participation of those closest to the couple, Finding Freedom is an honest, up-close, and disarming portrait of a confident, influential, and forward-thinking couple who are unafraid to break with tradition, determined to create a new path away from the spotlight, and dedicated to building a humanitarian legacy that will make a profound difference in the world.

She is But a Woman: Queenship in Scotland 1424–1463

Paperback – 6 October 2020 (US) & 6 August 2020 (UK)

She is But a Woman, the first in-depth study of medieval Scottish queens, investigates the relationship between gender and power in the medieval Scottish court by exploring the art of queenship as practised by Joan Beaufort and Mary of Guelders, queens of James I and James II. These women were excluded from authority but clearly possessed power as wives and mothers of kings. They established and cultivated relationships with members of the court, learned about Scottish political life and supported their husbands in the business of government. The book examines for the first time the arrivals of Joan and Mary in Scotland, their social and political status, their relationships with their husbands and families, and their roles in international diplomacy.

This modern re-evaluation of the role and power of the medieval queen is a thematic exploration rather than a biographical study. It situates the experiences of Joan and Mary within a broader European context and provides a new perspective on Scotland’s political, social and cultural links with Europe in the fifteenth century.

Ladies of Magna Carta: Women of Influence in Thirteenth Century England

Hardcover – 19 August 2020 (US) & 30 May 2020 (UK)

Including the royal families of England and Scotland, the Marshals, the Warennes, the Braoses and more, Ladies of Magna Carta focuses on the roles played by the women of the great families whose influences and experiences have reached far beyond the thirteenth century.

Women and Parliament in Later Medieval England (The New Middle Ages)

Hardcover – 4 August 2020 (US & UK)

This Palgrave Pivot provides the first ever comprehensive consideration of the part played by women in the workings and business of the English Parliament in the later Middle Ages. Breaking new ground, this book considers all aspects of women’s access to the highest court of medieval England. Women were active supplicants to the Crown in Parliament, and sometimes appeared there in person to prosecute cases or make political demands. It explores the positions of women of varying rank, from queens to peasants, vis-à-vis this male institution, where they very occasionally appeared in person but were more usually represented by written petitions. A full analysis of these petitions and of the official records of parliament reveals that there were a number of issues on which women consistently pressed for changes in the law and its administration, and where the Commons and the Crown either championed or refused to support reform. Such is the concentration of petitions on the subjects of dower and rape that these may justifiably be termed ‘women’s issues’ in the medieval Parliament.

Women and Economic Power in Premodern Royal Courts (Gender and Power in the Premodern World)

Hardcover – 31 August 2020 (US) & 30 June 2020 (UK)

From medieval England to early modern Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire, premodern kings and queens had splendid courts to show their God-given power. But where did the money for these come from? Following the money trail back often leads to financially savvy women―not only empresses and queens, but also mistresses and favourites―who skillfully managed huge estates, treasuries, or accounts. This volume focuses on how women used money as an instrument of power in early modern royal courts.

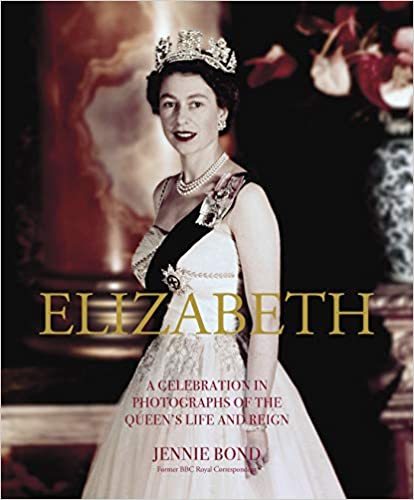

Elizabeth: A Celebration in Photos: A Celebration in Photographs of the Queen’s Life and Reign

Hardcover – 4 August 2020 (US) & 9 July 2020 (UK)

Queen Elizabeth II is the longest-serving monarch in British history. She has been a towering presence in British national life and throughout the world for almost 70 years and it is this extraodinary life that former BBC correspondent Jennie Bond explores and celebrates.

On February 6, 1952, Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, became Queen on the death of her father, King George VI. The reign that was to see major changes both in the country and Commonwealth and in the role of the monarchy began far away from Britain in a game reserve in Kenya. Elizabeth: A Celebration in Photographs, looks at this remarkable period in the history of Britain’s monarchy in lavish and fascinating detail, featuring over 240 photographs.

Anna of Denmark: The material and visual culture of the Stuart courts, 1589–1619 (Studies in Design and Material Culture)

Hardcover – 18 August 2020 (US) & 11 June 2020 (UK)

Approaching the Stuart courts through the lens of the queen consort, Anna of Denmark, this study is underpinned by three key themes: translating cultures, female agency and the role of kinship networks and genealogical identity for early modern royal women. Illustrated with a fascinating array of objects and artworks, the book follows a trajectory that begins with Anna’s exterior spaces before moving to the interior furnishings of her palaces, the material adornment of the royal body, an examination of Anna’s visual persona and a discussion of Anna’s performance of extraordinary rituals that follow her life cycle. Underpinned by a wealth of new archival research, the book provides a richer understanding of the breadth of Anna’s interests and the meanings generated by her actions, associations and possessions.

The Habsburgs: To Rule the World

Hardcover – 25 August 2020 (US) & 12 May 2020 (UK)

In The Habsburgs, historian Martyn Rady tells the epic story of the Habsburg dynasty and the world it built — and then lost — over nearly a millennium, placing it in its European and global contexts. Beginning in the Middle Ages, the Habsburgs expanded from Swabia across southern Germany to Austria through forgery and good fortune. By the time a Habsburg duke was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III in 1452, he and his clan already held fast to the imperial vision distilled in its AEIOU motto: Austriae est imperare orbi universe, “Austria is destined to rule the world.” Maintaining their grip on the imperial succession of the Holy Roman Empire for centuries, the Habsburgs extended their power into Italy, Spain, the New World, and the Pacific, a dominion that Charles V called “the empire on which the sun never sets.” They then weathered centuries of religious warfare, revolution, and transformation, including the loss of their Spanish empire in 1700 and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. In 1867, the Habsburgs fatefully consolidated their remaining lands the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, setting in motion a chain of events that would end with the 1914 assassination of the Habsburg heir presumptive Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, World War I, and the end of the Habsburg era.

Albania and King Zog: Independence, Republic and Monarchy, 1908-1939 (Albania in the Twentieth Century)

Paperback – 20 August 2020 (US & UK)

Albania in the Twentieth Century: A History represents an unparalleled achievement in scholarship on Albania. Owen Pearson presents a complete account of the twentieth century in Albania, from its breakaway from the Ottoman Empire in 1908 to the Kosova War in 1999. In fascinating detail, Pearson chronicles the monarchy of King Zog and the wartime period where Albania became a battleground for the Greek, Italian and German armies. He describes Enver Hoxha’s seizure of power, the country’s fraught relationship with the post-Stalin Soviet Union and Maoist China’s fraternal embrace of Albania, all leading to near-total isolationism and inevitable economic collapse. Pearson concludes with the genocide of Kosovar Albanians at the hands of the Serbian regime of Milosevic that characterised the last decade of twentieth century Albania. Comprising original research, and excerpts from rare Albanian sources, this is a compendium of primary source material that provides a year-by-year and sometimes day-by-day account of Albania’s modern history. It is an essential reference for all those interested in Albanian Balkan and Eastern European history.

Blood Royal: Dynastic Politics in Medieval Europe (The James Lydon Lectures in Medieval History and Culture)

Hardcover – 6 August 2020 (US) & 9 July 2020 (UK)

Throughout medieval Europe, for hundreds of years, monarchy was the way that politics worked in most countries. This meant power was in the hands of a family – a dynasty; that politics was family politics; and political life was shaped by the births, marriages and deaths of the ruling family. How did the dynastic system cope with female rule, or pretenders to the throne? How did dynasties use names, the numbering of rulers and the visual display of heraldry to express their identity? And why did some royal families survive and thrive, while others did not? Drawing on a rich and memorable body of sources, this engaging and original history of dynastic power in Latin Christendom and Byzantium explores the role played by family dynamics and family consciousness in the politics of the royal and imperial dynasties of Europe. From royal marriages and the birth of sons, to female sovereigns, mistresses and wicked uncles, Robert Bartlett makes enthralling sense of the complex web of internal rivalries and loyalties of the ruling dynasties and casts fresh light on an essential feature of the medieval world.

The Daughters of George III: Sisters and Princesses

Hardcover – 30 August 2020 (UK) & 19 November 2020 (US)

In the dying years of the 18th century, the corridors of Windsor echoed to the footsteps of six princesses. They were Charlotte, Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary, Sophia, and Amelia, the daughters of King George III and Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Though more than fifteen years divided the births of the eldest sister from the youngest, these princesses all shared a longing for escape. Faced with their father’s illness and their mother’s dominance, for all but one a life away from the seclusion of the royal household seemed like an unobtainable dream. The six daughters of George III were raised to be young ladies and each in her time was one of the most eligible women in the world. Tutored in the arts of royal womanhood, they were trained from infancy in the skills vial to a regal wife but as the king’s illness ravaged him, husbands and opportunities slipped away. Yet even in isolation, the lives of the princesses were filled with incident. From secret romances to dashing equerries, rumours of pregnancy, clandestine marriage and even a run-in with Napoleon, each princess was the leading lady in her own story, whether tragic or inspirational. In The Royal Nunnery: Daughters of George III, take a wander through the hallways of the royal palaces, where the king’s endless ravings echo deep into the night and his daughters strive to be recognised not just as princesses, but as women too.

Catherine the Great: A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works (Significant Figures in World History)

Hardcover – 15 July 2020 (UK) & 15 August 2020 (US)

Catherine the Great: A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works covers all aspects of her life and work. Empress Catherine the Great was one of the most famous and amazing women in world history. -Includes a detailed chronology of Catherine’s life, family, and work. -The A to Z section includes the major events, places, and people in Catherine’s life. -The bibliography includes a list of publications concerning her life and work. -The index thoroughly cross-references the chronological and encyclopedic entries.

The Grand Ducal House of Hesse

Hardcover – 15 August 2020 (US)

This is the third German dynasty that Eurohistory publishes a book about, the first two being the Ducal House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the Royal House of Bavaria (Volume I). This project is the culmination of more than two decades of research conducted by the authors. Beéche having already cooperated on several books and articles with Ms. Miller, a regular contributor to Eurohistory, pairing for another collaborative project was seamless. The Hesse and by Rhine Dynasty is one which Ms. Miller, better-known for her extensive work on the four daughters of Grand Duchess Alice of Hesse and by Rhine, with particular interest on Victoria Milford Haven, also feels passionately about. The result of years of research in Europe allowed Ms. Miller a unique insight into the lives of these four tragic sisters. The storyline begins in 1567. This was the year when the sons of Landgrave Philip “the Magnanimous” divided his vast lands among them. All branches of the Hessian dynasty stem from this territorial division. The Grand Ducal House of Hesse and by Rhine is among the most important German dynasties. Its members form a kaleidoscope of unique human beings: military and religious leaders, peculiar and heroic figures, talented artists and scientists, patrons of the arts and music, visionary and romantic architects, lucky and tragic people, dilettantes more interested in passing by than making a mark. They simply had it all. Their mark, not only in Darmstadt, but also throughout the Rhineland, is palpable in nearly every aspect of the region’s history, arts, letters, music, and architecture.

Sophia – Mother of Kings: The Finest Queen Britain Never Had

Paperback – 30 May 2020 (UK) & 19 August 2020 (US)

When Sophia Dorothea of Celle married her first cousin, the future King George I, she was an unhappy bride. Filled with dreams of romance and privilege, she hated the groom she called pig snout and wept at news of her engagement. In the austere court of Hanover, the vibrant young princess found herself ignored and unwanted. Bewildered by dusty protocol and regarded as a necessary evil by her husband, Sophia Dorothea grew lonely as he gallivanted with his mistress under her nose. When Sophia Dorothea plunged headlong into a passionate and dangerous affair with Count Phillip Christoph von Konigsmarck, the stage was set for disaster. This dashing soldier was as celebrated for his looks as his bravery, and when he and Sophia Dorothea fell in love, they were dicing with death. Watched by a scheming and manipulative countess who had ambitions of her own, it was only a matter of time before scandal gripped the House of Hanover and tore the marriage of the heir to the British throne and his unhappy wife apart. Divorced and disgraced, Sophia Dorothea was locked away in a gilded cage for 30 years, whilst her lover faced an even darker fate. The story of Sophia:Mother of Kings haunted George I to his dying day.

The post Book News August 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 16, 2020

Catherine the Great – An Empress-in-waiting (Part two)

Sophie had arrived at the Russian court as a 14-year-old German Princess to marry the 15-year-old Grand Duke Peter – heir and nephew of Empress Elizabeth of Russia – accompanied by her mother, Johanna. They were received like Queens, much to Johanna’s delight who considered the match her personal triumph. Sophie wrote of those first days, “He seemed glad to see my mother and me… In that short space of time, I became aware that he cared little for the nation over which he was destined to rule, that he remained Lutheran, did not like his entourage, and was very childish. I kept silent and listened, which helped gain his confidence.”1

Sophie soon realised that she must learn Russian and become orthodox to win the love of the people and their Empress. Her lessons began a week after her arrival, and she threw herself into it to such an extent that she developed a cold which turned in pneumonia. Johanna opposed Elizabeth’s doctors who wanted to bleed Sophie much to Elizabeth’s annoyance. Elizabeth then had Johanna removed from the room. She was bled 16 times over the following 27 days. As Sophie was in and out of consciousness, her reputation was already growing when stories were spread as to how she became ill. She did not appear in court again until her birthday in early May.

Meanwhile, Sophie’s mother Johanna had not made herself popular at court, and after a terrible scene, Sophie feared both of them were being sent home. It was decided that Johanna would go home as soon as the wedding had taken place. On 9 July 1744, Sophie was admitted into to the Russian Orthodox Church. She became Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseyevna or Catherine in English. Elizabeth had chosen the name for her; it had been the name of her own mother. The following day, her official betrothal to Peter was celebrated. Catherine gained precedence over her mother, and her mother wrote, “My daughter conducts herself very intelligently in her new situation. She blushes each time she is forced to walk in front of me.”2 The wedding itself was postponed as Peter had not hit puberty yet and during this time, Peter was very ill twice and even came down with smallpox.

Catherine had never had smallpox and was kept away from him, and when she saw him again, she was horrified. His face had been rendered barely recognisable by the smallpox scars. Empress Elizabeth decided that the wedding should now go ahead, she could wait no longer. It finally took place on 1 September 1745 with Catherine dressed in a silver brocade wedding dress, which was “horribly heavy.”3 Elizabeth escorted Peter and Catherine to the nuptial bed herself. They were then separated, and Catherine dressed in a pink nightgown before she was put to bed and there she waited….and waited. Eventually, Peter arrived drunk and reeking of tobacco and promptly fell asleep beside her. Their union would remain unconsummated for nine years. Not long after, Johanna was finally sent home, and she left huge debts behind.

Catherine was now alone with a husband who cared little for her, and she lived under the eye of the overbearing Empress Elizabeth. As time passed, Elizabeth became more anxious for an heir to appear. On 16 March 1747, Catherine’s father died after suffering a stroke, and Catherine was devastated. Elizabeth refused to allow her to mourn for more than a week and forced her to appear in public – as a concession she was allowed to wear black silk for six weeks. Elizabeth also tried to force Peter and Catherine in closer confinement, hoping that they would produce an heir. It was no use as Peter would use the nighttime in Catherine’s bed to play with his toys. It is unclear why the marriage remained unconsummated for so long. Catherine herself suggested that a doctor recommended that they wait until Peter was 21. Did he perhaps suffer from phimosis, or was the problem psychological? In any case, Catherine, who knew little about sex, could not have known.

As Peter’s behaviour became increasingly unpredictable, Catherine was stuck with him. She found refuge in books and devoured everything she could find. In the summer of 1752, Catherine met Sergei Saltykov, who was married to one of Elizabeth’s ladies-in-waiting. He was soon whispering in her ear, and she initially fended him off. Their affair began sometime in August or September 1752. Around the same time, Peter was introduced to sex by a certain Madame Groot, and supposedly he reluctantly underwent an operation for his phimosis. At the end of 1752, Catherine became pregnant for the first time, but she suffered a miscarriage not much later. In May 1753, she was pregnant again, but she suffered another miscarriage at the end of June. She later wrote, “I must have been pregnant two or three months. For 13 days, my life was in danger, and it was suspected that part of the after-birth had not been expelled. Finally, on the 13th day, it came out without pain or effort.”4

By February 1754, Catherine was pregnant again. This time, everything went according to plan. In August, she returned to the Summer Palace where two rooms were prepared for her in the Empress’ own suite. Here, Sergei would be unable to visit her. As her labour pains began, she was placed on a traditional labour bed – a mattress on the floor. On 1 October 1754, Catherine gave birth to a son and heir after a long and difficult labour. Elizabeth named him Paul. For the following three hours, Catherine was neglected as she lay in the labour bed. Only then was she placed back in her own bed. She would not see her own son for a week. Sergei was assigned to a special diplomatic mission. Catherine herself would always insist in her private writings that Paul was her lover’s son. In any case, Paul did not grow up to look like Sergei – but he did look and act just like Peter. We’ll never know for sure.

For many months, Catherine was depressed, and she refused to leave her room. Once again, she turned to her beloved books. She resolved that she would defend her position from now on. She was, after all, the mother of the heir. She even confronted Peter, who was left thoroughly confused by her behaviour. She was becoming her own woman and embarked on several love affairs. In 1757, she fell pregnant again, probably by Stanisław Poniatowski. Peter sighed out loud, “God knows where my wife gets her pregnancies. I have no idea whether this child is mine and whether I ought to take responsibility for it.”5 On 9 December 1757, Catherine gave birth to a daughter named Anna who would die in infancy. Once more, the baby was snatched away. Catherine never mentioned her death in her memoirs.

Soon, she met Gregory Orlov, though it is unclear when exactly they met for the first time. They became lovers in the summer of 1761. Meanwhile, Empress Elizabeth’s health was steadily deteriorating. Peter became more vocal in his sympathies for Prussia and how he wished to divorce Catherine. He intended to immediately end the war with Prussia as soon as he became Emperor. Unlike him, Catherine’s absolute devotion was to Russia. The idea of a coup was born.

Part three coming soon.

The post Catherine the Great – An Empress-in-waiting (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 15, 2020

Sophia: Mother of Kings: The Finest Queen Britain Never Had by Catherine Curzon Book Review

Sophia of Hanover would have been Queen of Great Britain if she had lived just a few months longer. In the end, she died only two months before Queen Anne, and it was Sophia’s eldest son who became King George I of Great Britain. The youngest daughter of the famous Winter Queen, Elizabeth Stuart, and thus a granddaughter of King James VI and I, it hardly seemed likely that Sophia would one day rule in her own right. Yet, as the Stuart line died out or was exiled for being Catholic and Sophia’s elder siblings were excluded for being Catholics, the succession was vested in Sophia’s Hanoverian line.

Sophia married the future Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover at the age of 28 – rather late for the time. They went on to have seven children who lived to adulthood. Her daughter Sophia Charlotte became Queen of Prussia.

Catherine Curzon traces the life of the would-be Queen from her childhood days in exile to her married life. Sophia: Mother of King’s is well-researched and easy to read, even if you are not well-read on the subject. It’s a must-read if you’re interested in the Hanoverian dynasty – Sophia certainly would have made a formidable Queen. The only negative point for me – which is a matter of taste – is the cover. It just doesn’t do her justice at all.

Sophia: Mother of Kings: The Finest Queen Britain Never Had by Catherine Curzon is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Sophia: Mother of Kings: The Finest Queen Britain Never Had by Catherine Curzon Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 14, 2020

Catherine the Great – The little-known German Princess (Part one)

In the early hours of 2 May 1729, 16-year-old Princess Johanna Elisabeth of Holstein Gottorp, wife of the 39-year-old Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, gave birth to her first child in a merchant’s house in Szczecin (in present-day Poland). The house served as temporary quarters for her husband, who was stationed there as a general in the service of King Frederick William I of Prussia. It had been a long, painful, and life-threatening delivery, and the parents were disappointed with the birth of a girl. Her name was Sophie Augusta Fredericka. She would be known in history as Catherine the Great.

Sophie’s childhood was mostly spent at her birthplace because her father did not become the ruling Prince of Zerbst until 1743. Her relationship with her mother was somewhat distant – as was usual for the time. Johanna handed her child over to the servants and wetnurses. Johanna would give birth to four more children after Sophie but only one other child – a son named Frederick August – lived to adulthood. Sophie later wrote, “It was told me that I was not very joyfully welcomed… My father thought I was an angel; my mother did not pay much attention to me. A year and a half later, she (her mother) gave birth to a son whom she idolised. I was merely tolerated, and often I was scolded with a violence and anger I did not deserve. I felt this without being perfectly clear why in my mind.”1

Sophie’s governess Elizabeth Cardel was entrusted with overseeing her education. With her, Sophie finally found some warmth. She later wrote, “She had a noble soul, a cultured mind, a heart of gold; she was patient, gentle, cheerful, just, consistent – in short the kind of governess one would wish every child to have.”2 Johanna decided that Sophie was becoming too arrogant and proud and began to tell her daughter that she was ugly and that she was not allowed to speak unless someone spoke to her. Sophie bowed to her mother’s will. From around the age of eight, Johanna took Sophie with her on her travels if only to introduce her to society. Sophie soon realised that marriage would be the only way away from her mother, and these travels introduced her to foreign courts. She did not want to end up like her aunt who lived with her 16 pug dogs and several parrots which did their business in the same room as where she lived. Sophie later wrote, “One can imagine the fragrance which reigned there.”3

In 1739, Johanna’s brother Adolf Frederick became the guardian of the orphaned Charles Peter Ulrich of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp, son of Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp and Anna Petrovna of Russia. He was the only living grandson of Peter the Great, Emperor of Russia and he was just one year older than Sophie. Johanna gathered up her daughter and took her for a visit with her uncle. Sophie met her future husband for the first time around this time. Sophie was now growing into a beautiful young woman and was noticed by a Swedish diplomat who told her mother, “Madame, you do not know the child. I assure you she has more mind and character than you give her credit for.”4

At the age of 14, Sophie had a short flirtation with her young uncle, Georg Ludwig. He suddenly proposed to her, leaving her dumbfounded. She hesitantly accepted his proposal, but only if her parents wished it. A letter from Russia would throw all her uncle’s plans in the wind.

Empress Elizabeth of Russia, a younger daughter of Peter the Great, had seized the throne in a coup and Johanna immediately wrote her to congratulate her. She asked her “dear niece” to return a painting of her beloved sister Anne which Johanna had in her possession. Johanna had no problem with this favour and also dragged Sophie to Berlin to have her painted by Antoine Pesne. This painting would be sent to Elizabeth as a gift as well. Elizabeth had been engaged to Johanna’s elder brother Charles August who had died of smallpox a few weeks before the wedding. Elizabeth was devastated and began to consider the Holstein’s as part of her family. When Johanna gave birth to her fifth and final child in 1742, she was promptly named Elizabeth in honour of the Empress. Tragically, the girl died in infancy. That same year, Elizabeth adopted the aforementioned Peter – the son of her elder sister Anne – as her heir. As a condition of becoming heir to the Russian, he had to renounce his claim to the Swedish throne and Elizabeth choose a new successor to the Swedish throne – Johanna’s brother Adolf Frederick. The family’s fortunes were looking up.

The following year also saw the family move to Zerbst, where Sophie’s father was now the reigning Prince. Shortly after the New Year’s Day service of 1744, another letter arrived from Russia – summoning Johanna and Sophie to Russia. A second letter stated, “I will no longer conceal the fact that in addition to the respect I have always cherished for you and for the princess your daughter, I have always had the wish to bestow some unusual good fortune upon the latter; and the thought came to me that it might be possible to arrange a match for her with her cousin, the Grand Duke Peter of Russia.”5 Notably, Sophie’s father was excluded from the invitation as Elizabeth probably realised he would resent his daughter having to change religion. Nevertheless, he felt like he had no choice and reluctantly gave his approval. Elizabeth sent money for the journey which Johanna used to improve her wardrobe – nothing was left for Sophie.

On 10 January 1744, Sophie and her parents entered a carriage which headed to Berlin where they were to meet King Frederick of Prussia. Sophie would never return to Zerbst. Once at the Berlin Court, Johanna claimed Sophie could not be presented to the King because she had no court dresses. Frederick immediately sent over a gown belonging to one of his sisters. Sophie was presented to him in a gown that did not fit, without any jewellery and not having had her hair powdered.

Nevertheless, it was she who sat at the King’s table and not her parents. She managed to please him with her intelligent answers to his questions. Frederick wrote to Elizabeth in praise of Sophie.

On 16 January, Sophie and her parents left Berlin, and she said goodbye to her father at Schwest. Both wept as they said their goodbyes and they never saw each other again. The journey to St Petersburg was difficult, and they only reached the Winter Palace on 14 February. They were given an Imperial welcome, but Empress Elizabeth was not there – she had already travelled to Moscow. While Johanna enjoyed being treated like a Queen, Sophie was more interested in the 14 elephants that performed tricks in the courtyard – they had been a gift to the Empress from the Shah of Persia. Johanna and Sophie were being fitted with Russian wardrobes before proceeding to Moscow. They left on 16 February to make it to Moscow in time for Grand Duke Peter’s 16th birthday on 21 February. This time, the roads were snowed over, making the journey much smoother.

In the evening of 20 February 1744, 14-year-old Sophie met Empress Elizabeth and her future husband Grand Duke Peter for the first time. Sophie later wrote, “It was quite impossible on seeing her for the first time not to be astonished by her beauty and the majesty of her bearing.”6 Soon, Sophie and Peter would be married, and the little known German Princess was no more.

Part two coming soon.

The post Catherine the Great – The little-known German Princess (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.