Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 176

June 20, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of Alexander, Prince of Orange

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands had three elder half-brothers, but she would not know any of them. The three sons of the marriage of her father, King William III of the Netherlands and his first wife Sophie of Württemberg, were William (nicknamed Wiwill), Maurice and Alexander. Maurice fell ill with meningitis in early 1850, and he died at the age of six on 4 June 1850. Though William and Sophie’s marriage was famously unhappy, they managed to reconcile long enough for Sophie to fall pregnant again. Alexander was born on 25 August 1851. His elder brother William had become Prince of Orange, the title for the heir to the throne, in 1849 when their father became King.

(public domain)

(public domain)The birth was a little premature, and Sophie took a long time to recover. She was initially feverish and restless, as was her young son. It soon became apparent that young Alexander was the opposite of his lively elder brother William. Sophie worried about him and spoiled him. As he grew older, Sophie admitted that he was “a strange boy with a character filled with contrasts.”1 He wasn’t sent to school and was instead homeschooled by his overbearing mother. When travelling, the pair often visited areas known for their good air. Doctors did not give any conclusion as to what, if anything, was wrong with Alexander, but Sophie concluded that he was facing “a life of misery.”2 He had a growth spurt in 1867 that left him with a slightly curved spine.

After his 18th birthday, he also travelled to spas without his mother. At the end of 1869, he even went on a long trip onboard a naval ship to the Mediterranean. Sophie was devastated and wrote, “My boy is leaving in the first week of December, and since the date has been set, it feels like my death sentence has been signed.”3 He also took classes at University but never graduated.

In 1874, Alexander moved into his own palace in The Hague, but by the end of the year, he was off travelling again. His mother hoped that he would meet a nice and suitable Princess, and she focussed on Princess Thyra of Denmark. This match never took place. Sophie wrote, “My sons are well. If only they would get married, then I would have no reason to complain.”4 His elder brother William had fallen in love with a Dutch Countess and his father absolutely refused to give his permission for their marriage. William moved away to Paris, where he lived a debauched lifestyle.

On 3 June 1877, Alexander lost his mother. He was devastated and wrote, “I am now so lonely and abandoned in this big world that your affection is a support to me to keep walking the path of life. My life is broken, my happiness, my daily life, the conversations with my beloved and lamented mother – destroyed.”5 Sophie laid in state for three days and Alexander refused to leave her side. As her coffin was lowered into the crypt at Delft, Alexander threw himself onto the coffin as he wept. William, whose return to the Netherlands for the funeral of his mother would be the last visit, had to pull him off. From then on, Alexander began to save everything that had something to do with his mother.

In his loneliness, his thoughts returned to marriage, and this time the focus was on Frederica of Hanover, but she was in love with someone else. Alexander gave up all thoughts of marriage and wrote, “Give me the freedom to walk my lonely path of life alone. I know very well that with the passing of my dear mother, I am now completely alone in the world.”6 He began collecting butterflies and miniatures, slowly turning his palace into a museum. He wrote, “My sadness has had a strange development.”7

King William III was also thinking of marrying again, much to the dismay of his sons. Alexander saw the remarriage as an insult to his late mother, but he kept the high ground and remained polite. He was not present for the wedding of King William and Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont in Arolsen in January 1879. He left for France and told his staff to keep the palace windows shut as a sign of mourning. When he returned, he refused to meet Emma. On 11 June 1879, his elder brother William died in France at the age of 38. Alexander was summoned and placed a picture of their mother in his brother’s hands. Alexander now became the new Prince of Orange.

As the new Crown Prince, Alexander requested a meeting with his father, but he also unwillingly came face to face with his new stepmother. He decided against leaving and bowed for her. However, they don’t have a conversation as Alexander was rather angry with his father for putting him in this situation. To escape the situation, Alexander went to stay with his aunt Marie of Württemberg in Switzerland. He refused to appear at the opening of parliament, and a following newspaper article was personally rebuffed by Alexander. His speaking to the press led to quite a commotion, and newspapers quickly sold out. He withdrew into his own palace even more, and his parrot and dog were his only companions.

(public domain)

(public domain)On 31 August 1880, Emma gave birth to Alexander’s half-sister Wilhelmina. Alexander would never meet her. By May 1884, Alexander was seriously ill with typhoid fever. King William was in Karlsbad while Emma and Wilhelmina were spending time in Kissingen, and none of them seemed too concerned with Alexander’s health. On 3 June, the first newspaper reports appeared. Despite his illness, Alexander ordered wreaths to be placed on his mother’s coffin on the anniversary of her death. When William was finally informed that Alexander was probably dying, he was convinced by his doctors to stay in Karlsbad. Alexander ordered his brother William’s bed – to one in which he had died – to be brought to him so that he could die in it as well.

The end came on 21 June 1884. His last words were, “Help me, please help me. I can take no more.”8 He died at 2 in the afternoon. King William ordered the windows at Noordeinde Palace to be shut. However, he delayed his return to the Netherlands, and so Alexander remained unburied for nearly a month. He was finally interred in Delft on 17 July. King William was the first to leave the funeral.

With his death, King William now had just one living legitimate child… Wilhelmina.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of Alexander, Prince of Orange appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 19, 2020

Book News July 2020

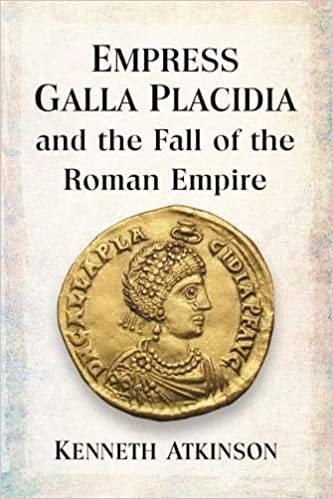

Empress Galla Placidia and the Fall of the Roman Empire

Paperback – 27 June 2020 (US) & 30 July 2020 (UK)

Despite being one of history’s most important women, the story of Galla Placidia’s life has been largely forgotten. Though the Roman empress witnessed the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century and lived a life of almost constant suffering, her actions helped postpone the fall of Rome and had massive, widespread impact on the empire that can still be felt today. She watched the barbarian king Alaric and his horde of Visigoth warriors sack Rome, slaughter many of the city’s inhabitants, and take her hostage. Surviving captivity, Galla Placidia became the queen of the barbarians who had imprisoned her. Eventually, she became the only woman to rule the Roman empire alone. Soldiers obeyed her commands while Popes and Christian saints alike sought her advice. Despite all obstacles and likely suffering from PTSD, she lived to old age. This book uses the letters and writings of Galla Placidia’s contemporaries to reconstruct, in more depth and detail than has yet been attempted, the remarkable story of her life and the decline and fall of the Roman Empire.

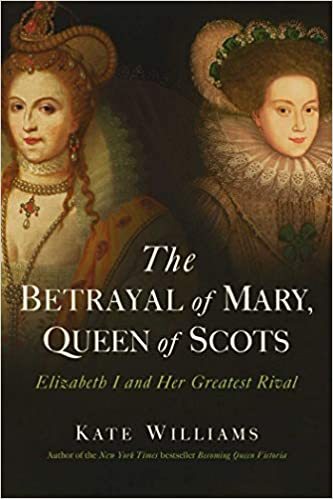

The Betrayal of Mary, Queen of Scots: Elizabeth I and Her Greatest Rival

Paperback – 14 July 2020 (UK & US)

Elizabeth and Mary were cousins and queens, but eventually it became impossible for them to live together in the same world.

This is the story of two women struggling for supremacy in a man’s world, when no one thought a woman could govern. They both had to negotiate with men–those who wanted their power and those who wanted their bodies–who were determined to best them. In their worlds, female friendship and alliances were unheard of, but for many years theirs was the only friendship that endured. They were as fascinated by each other as lovers; until they became enemies. Enemies so angry and broken that one of them had to die, and so Elizabeth ordered the execution of Mary.

But first they were each other’s lone female friends in a violent man’s world. Their relationship was one of love, affection, jealousy, antipathy–and finally death.

This book tells the story of Mary and Elizabeth as never before, focusing on their emotions and probing deeply into their intimate lives as women and queens. They loved each other, they hated each other–and in the end they could never escape each other.

The Crown in Crisis: Countdown to the Abdication

Hardcover – 9 July 2020 (UK)

Using previously unpublished and rare archival material, and new interviews with those who knew Edward and Wallis, The Crown in Crisis is the conclusive exploration of how an unthinkable and unprecedented event tore the country apart, as its monarch prized his personal happiness above all else. This seismic event has been written about before but never with the ticking-clock suspense and pace of the thriller that it undoubtedly was for all of its participants.

The Crown in Crisis is the definitive book about the events of 1936. Painstakingly researched, incisively written and entirely fresh in its approach, it will bring the events of that time to thrilling life, and in the process appeal to an entirely new audience.

Isle and Empires: Romanov Russia, Britain and the Isle of Wight

Hardcover – 7 July 2020 (UK)

The tumultuous story of the Romanovs and their enigmatic relationship with Britain is brought to life in Stephan Roman’s Isle and Empires, as he explores the misunderstandings, suspicions and alliances that created an uneasy partnership between two of the world’s most powerful Empires. The Isle of Wight was at the heart of this relationship, an island off the south coast of England that intimately linked the British royal family and the Romanovs. Peter the Great drew inspiration for the first Russian naval fleet from his sailing trips around the Island, and Alexander I was immortalised by a hilltop monument built for him on St Catherine’s Down. Alexander II’s beloved only daughter, Grand Duchess Marie, spent many years at Osborne House infuriating and irritating her mother-in-law, Queen Victoria. In contrast to the Isle of Wight’s imperial and royal connections, Russian revolutionaries also made it their home, establishing a summer colony of radical political thinkers and writers in Ventnor. In August 1909 the Island hosted the Russian Imperial family during their visit to Cowes Week, then the most glamorous yachting regatta in Europe’s social calendar. A new era of Anglo-Russian collaboration was dawning and seemed destined to become a dominant force in 20th century global politics. The Tsar’s visit to Cowes was deliberately intended to set the seal on this new alliance. Less than ten years later the Romanovs had been overthrown, with the British government and royal family accused of betrayal and complicity in their deaths. Isle and Empires is a journey into a world of Imperial glory and power, family rivalry, wars, intrigue and alliances. It is also a story of Russia’s revolutionaries, spies and terrorists, and the refugees fleeing Tsarist oppression who found shelter and safety both in mainland Britain and on the Isle of Wight. These events reverberate to the present day and much of what happened when the Romanovs ruled Russia continues to set the pattern for the current relationship between the two countries.

Uncrowned Queen: The Life of Margaret Beaufort, Mother of the Tudors

Hardcover – 28 July 2020 (US & UK)

In 1485, Henry VII became the first Tudor king of England. His victory owed much to his mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort. Over decades and across countries, Margaret had schemed to install her son on the throne and end the War of the Roses. Margaret’s extraordinarily close relationship with Henry, coupled with her role in political and ceremonial affairs, ensured that she was treated — and behaved — as a queen in all but name. Against a lavish backdrop of pageantry and ambition, court intrigue and war, historian Nicola Tallis illuminates how a dynamic, brilliant woman orchestrated the rise of the Tudors.

Elizabeth: A Celebration in Photographs of the Queen’s Life and Reign

Hardcover – 9 July 2020 (UK) & 4 August 2020 (US)

Queen Elizabeth II is the longest-serving monarch in British history. She has been a towering presence in British national life and throughout the world for almost 70 years and it is this extraordinary life that former BBC correspondent Jennie Bond explores and celebrates.

On February 6, 1952, Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, became Queen on the death of her father, King George VI. The reign that was to see major changes both in the country and Commonwealth and in the role of the monarchy began far away from Britain in a game reserve in Kenya. Elizabeth: A Celebration in Photographs, looks at this remarkable period in the history of Britain’s monarchy in lavish and fascinating detail, featuring over 240 photographs.

Constantly under scrutiny ever since she took the throne, this book presents a balanced and absorbing account of the Queen’s life and of her role as the head of state in a country and a world that have changed almost beyond recognition in the seventy years since she inherited the throne.

The post Book News July 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 18, 2020

Royal Confinements by Jack Dewhurst Book Review

Royal Confinements was first released in 1980 and has recently been re-released with an additional chapter focussing on a few cases post-Queen Victoria. It tracks the obstetric history of the British Royals from Catherine of Braganza to – originally – Queen Victoria. It is not limited to Queens.

Some had very tragic stories, such as Queen Anne and Princess Charlotte. Some are success stories. Royal Confinements is very interesting indeed and is one of the rare books that focusses on what was perhaps the most important part of royal life for women – the need to produce an heir.

Overall, the book is well-researched and quite easy to read. I did notice quite a few errors. Queen Victoria’s mother is referred to as Mary, and although one of her names is certainly Marie, I have never seen her referred to as anything other than Victoire/Victoria. Her elder daughter from her first marriage is called Theodora while she was actually Feodora. The child born to the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 1819 is referred to as the heir apparent to Great Britain and Hanover, even though he was still behind several uncles who could technically still produce children (sons in the case of Hanover, which had Salic law). Even if he was the only grandson in his generation, he would still be the heir presumptive until his father became King. It seems strange that while the publisher took the time to note that Queen Victoria was no longer the longest-reigning British, it did not notice some of these errors.

The additional chapter picks up with King Edward VII and briefly scoots through the main players of the 20th century into the early 21st century. Tragically, this book also falls foul with their use of “Princess Diana” and calling out the Duchess of Cambridge for “breaking the rule” for wanting to have her children in hospital. I thought we were past the time when women had no say in giving birth. The Duchess of Sussex is also referred to as “Meghan Markle” even after she is married and in the final paragraphs, their son’s name is discussed – not sure how that was relevant.

I am not sure how the original book was served with this reprint. The book left an overall bad taste in my mouth despite its original author’s (probable) best intentions.

Royal Confinements by Jack Dewhurst is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Royal Confinements by Jack Dewhurst Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 17, 2020

Marie of Saxe-Altenburg – An exiled Queen (Part two)

Then came the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, and George supported Austria. However, Austria lost the war, and as a result, Prussia annexed Hanover, causing George and Marie to be expelled from their Kingdom. George never abdicated the throne, and following the loss, he and his son went to Vienna while Marie and their daughters remained in Hanover at the Herrenhausen Palace. Marie sent an encouraging letter to him, “Oh my angel Männi, act accordingly if it is going to be difficult. You will never regret it. Giving in now, after you’ve done everything so bravely, is only honourable and will be generally recognised as the highest nobility. Your actions are always so noble and sublime.”1 She soon felt unsafe at Herrenhausen and left for the nearly finished Marienburg, which she called her “Eldorado.” Marie managed to have several jewels smuggled abroad before she also left for Austria.

Emperor Franz Joseph gave the exiled family the use of the Braunschweig Villa and the so-called Kaiserstockl. At Kaiserstockl, Marie and George celebrated their silver wedding anniversary. The family was eventually allowed to retain several properties such as Marienburg, and they were given an annual pension from the interest of a restitution payment of 16 million thalers. Eventually, the family settled in Gmunden at Villa Thun, later known as the Queen’s Villa. Marie later wrote, “You can all return home from exile whenever you want, but we cannot because we continue to live in exile. That is a feeling, that is heavy to bear. […] But I take comfort from God’s word every day. I feel far happier here in Gmunden than in Vienna, where the heat is often so oppressive and the dust so unbearable. But I can rejoice in the beautiful nature and stand up in rural loneliness.”2

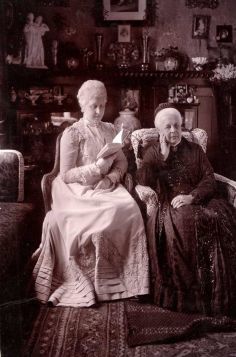

Princess Marie and Queen Marie (public domain)

Princess Marie and Queen Marie (public domain)From 1874, George was often ill, and he underwent an operation. He went to recuperate in Biarritz and from then on lived mainly in Paris due to its milder climate and proximity to the springs of Barèges. He was often accompanied by his elder daughter Frederica, while his younger daughter Marie and his son stayed with their mother. He returned to Gmunden just once – in 1877 – but he would die in Paris on 12 June 1878. George was taken to St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle for burial and Marie did not attend his funeral, preferring to mourn him in silence at Gmunden. While Ernest Augustus did not succeed his father as King, he did succeed in his English title of Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale.

At the end of 1878, Ernest Augustus married Princess Thyra of Denmark and Marie’s first grandchild – a daughter named Marie Louise – was born on 11 October 1879. Ernest Augustus and Thyra would go on to have six children together. Frederica married Baron Alfons von Pawel-Rammingen in 1880, but tragically, their only child would live for just three weeks. Her youngest daughter and namesake would remain unmarried, and she stayed with her mother. The two Maries visited the spas at Bad Kissingen at least once a year, and they often entertained at Gmunden.

As she grew older, she lost sight in one of her eyes. Marie always dressed in mourning clothes after her husband’s death and only took it off for the first time when her granddaughter Marie Louise married Prince Max of Baden in 1900. She was devastated by the sudden death of her 16-year-old grandson Prince Christian appendicitis in 1901. Still, an even bigger blow came on 4 June 1904 when her daughter and namesake also fell ill with appendicitis. Despite an emergency operation, Marie could not be saved. She was 54 years old.

Queen Marie of Hanover would live to be 88 years old. She died on 9 January 1907 of peritonitis. Emperor Franz Joseph personally attended her funeral with several Archdukes and Archduchesses. She was buried in the mausoleum her son had built at Schloss Cumberland, also in Gmunden. She was buried next to her daughter Marie.

The post Marie of Saxe-Altenburg – An exiled Queen (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 16, 2020

Marie of Saxe-Altenburg – An exiled Queen (Part one)

Marie of Saxe-Altenburg was born on 14 April 1818 as the daughter of Joseph, Duke of Saxe-Altenburg and Duchess Amelia of Württemberg. She would be the eldest of six sisters, though two of them would die in infancy. Marie was only seven years old when her younger sister Pauline died at the age of five. When Marie was 15 years old, Louise died at the age of only 14 months.

Marie spent the first seven years of her life in Hildburghausen before the entire family moved to Altenburg. Marie and her sisters received their religious education primarily from the Lutheran priest Carl Ludwig Nietschze (father of the famous philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche). Marie spent a lot of time with her family on the island of Norderney, and her future husband also visited it several times.

George was the eldest son of Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover (uncle of Queen Victoria and her heir presumptive until the birth of the Princess Royal) and Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. While the United Kingdom operated on the basis male-preference primogeniture, which allowed Queen Victoria ascend the throne, the Kingdom of Hanover allowed only males to succeed and so Ernest August became King of Hanover – dissolving the personal union between Hanover and the United Kingdom. George was a delicate child and benefitted greatly from the sea air. In 1828, he lost the sight in one eye due to a childhood illness and the sight in the other eye in 1833 after an accident.

Marie and George met for the first time on 14 July 1839 at Schloss Montbrillant just outside Hanover. It is said they fell in love, and Marie’s cheerful disposition managed to lift his spirits, even after the death of his mother in June 1841. In April 1842, George travelled to Altenburg to be a part of the silver wedding celebrations of Marie’s parents. He took the opportunity to propose marriage to Marie. Ernest Augustus officially asked Queen Victoria’s permission for the marriage under the Royal Marriages Act 1772, and she gave her permission on a magnificent piece of parchment which is still housed at Marienburg Castle. Their engagement was announced in July 1842.

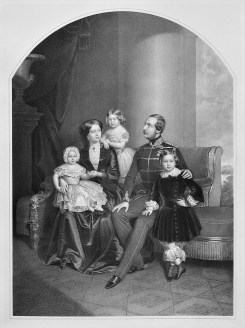

(public domain)

(public domain)The wedding took place on 18 February 1843 in Hanover. Marie had only arrived in Hanover two days before the wedding. The ceremony took place in the chapel of the Leineschloss, and cannon shots were fired as the rings were exchanged. Marie wore a white and silver silk and brocade dress with a long white train. On top of a green myrtle wreath, she wore the Hanoverian bridal crown. The newlyweds first lived at the Fürstenhof in the Calenberger Neustadt district of Hanover, but they also spent the summers at Schloss Montbrillant. These were the happiest days of their marriage. Soon after her arrival in Hanover, a politician wrote, “The Crown Princess is behaving well; she was well-received by the nobility, who know of nothing against her, she seems to be very well managed by the female need to please people. The Crown Prince is understandably entirely dependent on her. She will rule, for better or worse.”1

Their first child – a son named Ernest Augustus – was born at the Fürstenhof on 21 September 1845. He was presented to his proud grandfather on a velvet cushion trimmed with lace. George’s father had initially criticised George and Marie’s retiring lifestyle – blaming Marie for it – he now described his grandson’s day of birth as the happiest day of his life. He said to Marie, “Marie, how happy you make me.”2 However, he continued to find ways to criticise Marie. He abhorred the company she kept – non-noble people like artists and scholars – she nursed her own children and George, and she had nicknames for each other – “Männi” and “Engelmausi.” Her father-in-law banned her from attending his court while she was nursing her children. He also criticised the fact that the couple always arrived together in one carriage, rather than separately. Nevertheless, the couple was immensely popular with the people for their more bourgeois lifestyle. Two daughters were also born to the couple: Frederica (born 9 January 1848) and Marie (born 3 December 1849).

In the autumn of 1851, her father-in-law’s health began to deteriorate. In the early hours of 7 November, George and Marie rushed to be by his side as he suddenly became worse. However, he rallied enough to play with his grandchildren, even hugging his grandson and saying, “God bless you, my child!”3 He lost the ability to speak a few days later and fell into unconsciousness. He died on 18 November 1851 at 6.45 in the morning in the presence of George and Marie. George now became King George V of Hanover and Marie his Queen.

Marie turned her attention to her charitable work and founded the Henriettenstift in Hanover with money left to her by her grandmother Henriette. She was deeply pious and also championed the founding of several houses of worship. She also sponsored several musicians and was a talented singer herself. George loved hearing her sing, and he even composed songs for her to sing.

For her 39th birthday, George gave Marie a plot of land to build a new castle on. He stipulated that it should be called Marienburg and that she should use it as a summer residence. It was to be her personal property. Marie began planning for it with great enthusiasm and on 9 October 1858, the foundation was laid. Each of their three children took a turn with the hammer. They were finally able to stay for a few weeks in the summer of 1865.

Part two coming soon.

The post Marie of Saxe-Altenburg – An exiled Queen (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 15, 2020

Elena Vladimirovna of Russia – A Grande Dame (Part two)

After many years, they were able to return once more to Greece. Nicholas died in Athens on 8 February 1938 after suffering a heart attack. He said, “I am happy to die in my motherland, in my beloved country.”1 Elena moved into a villa in Athens from where she supported charities and the Russian community. Elena stayed in Greece during the Second World War, much to the worry of her family. She was near her sister-in-law Alice who had also remained behind. Alice wrote to her son Philip, “Even in these anxious times I am full of hope and when I go for walks I look at all the houses to see if there is not a suitable one for us later on, as I am tired of flat and prefer a whole house. Uncle Georgie’s house is very cold now as there is no means of working the central heating. Upstairs there is a room with a fireplace, so happily I have one warm in which to dress and sit and eat. Aunt Ellen (Elena) is well and lunches with me very often. We are the only one here and so we became very close friends…”2

When Elena’s son-in-law The Duke of Kent was killed in an air crash in 1942, Alice wrote, “It was an awful shock and she looks pale and tired. But she is very brave and will not show any weakness.”3 Both Alice and Elena were involved in charity and both were given petrol every month from the Swedish Relief Commission to be able to drive in and out of Athens. However, Elena lived in much more comfortable housing than Alice as reported by Harold Macmillan when he visited them in 1944. She was living in a large and comfortable villa and had been allowed to keep her radio. She also served him an excellent tea. She was also said to have pro-German sympathies. He wrote, “The Princess is a lady of fine presence. She must have been a beauty. The eyes, dark and lustrous, are remarkable. She reminded me of an Edwardian grande dame. Her conversation, though making the conventional references to the faults of the Germans, was more concerned with the dangers of revolution and Communism. EAM (a left-wing party) is, of course, anathema: ‘It must be stopped at once. It is the only chance. I know. It must be stopped.'”4 In contrast, he found Alice “in humble, not to say somewhat squalid conditions…”5

A French diplomat observed, “Princess Nicholas (Elena) was very religious and mystical. She would have gone to the stake for her religion. She had an energy and a will that Princess Andrew (Alice) didn’t have. She thought Princess Andrew did not understand religion. But Princess Andrew later founded the only order of nuns in Greece to do social work. She said, ‘It is all very well for Princess Nicholas forever attending the liturgy, but we must be practical.’ Psychologically Princess Andrew’s balance was frail, she had a German, dreamy philosophical approach to religion.”6

However, as some fighting continued in Athens it was considered safer for Elena to move in with Alice for the time being. Elena had initially resisted this until the driver of one British Major Green had been shot dead as they were heading towards her house. In December 1944, Alice wrote, “I am afraid you will be worrying about us but really we are all right & strongly guarded in our small free area of the town. We get British soldier’s rations which are excellent & Ellen & I especially enjoy the meat rations as we have not had any for many months. I really think we are much better off than we have been for a long time in the way of food. Although there is no electricity, we have a petroleum lamp to ourselves on the first floor, Ellen’s rooms being next to mine is a great convenience. The servants have the ground floor petroleum lamp. Friends come daily to see us & in the evening we play card games & make jokes & try to forget our tragic circumstances.”7 Elena was able to return home on 21 January 1945.

Elena enjoyed generally good health, though her house was “swarming with cats.”8She would eventually suffer a heart attack. Her two surviving daughters Olga and Marina – Elisabeth had died in 1955 of cancer – rushed to be by her side, arriving the night before her death. Crown Prince Constantine – later King Constantine II of Greece – was also there and she greeted him with a “Hello darling.”9 The news of her impending death was kept from Alice by Queen Frederica. Elena died on 13 March 1957. She was buried at the Royal Cemetery in Tatoi next to her husband.

The post Elena Vladimirovna of Russia – A Grande Dame (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 14, 2020

Elena Vladimirovna of Russia – A Grande Dame (Part one)

Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia was born on 17 January 1882 as the only daughter of Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia and Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. She would have three surviving older brothers; Kirill, Boris and Andrei.

She grew up surrounded by immense luxury and was therefore quite conscious of her exalted position as a Grand Duchess. She was born at Tsarskoe Selo, and she would spend most of her childhood and adolescence there. She was known to have quite a temper and once threatened a nurse with a paper-knife as she sat for a portrait. “The little lady then transferred her attentions to me, her black eyes ablaze with fury.”1

Her mother wanted Elena to make a brilliant match and considered several candidates for her. One of the first was Prince Albert of Belgium, who became King Albert I in 1909. However, he was already in love with Elisabeth in Bavaria. She then considered Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, who had been expected to one day succeed as King of Bavaria, but in this case, religion posed a problem. Rupprecht was a Catholic, and Elena would need to convert, something she would not do. He also married a Bavarian Princess.

While on holiday in Cannes with her mother, 16-year-old Elena met Prince Max of Baden and in 1898, they became engaged. However, the engagement was broken off just a few months later. Her eventual husband would be Prince Nicholas of Greece, the third son of King George I of Greece, and Queen Olga (born Olga Constantinovna of Russia). Elena had known him from childhood as the relatives from Greece often came over to Russia. He was not the heir to a throne Marie had hoped for, but over time, it would prove to be a loving match.

Elena and Nicholas were married on 29 August 1902 in the Grand Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. It was also her parents’ 28th wedding anniversary. Nicholas later wrote, “The wedding took place…in the chapel of the Grand Palace, its interior in dark blue and gold. It was decorated to the liking of Catherine the Great, with the splendour of that era. This time, instead of being an ordinary observer, I became not just one of the main characters but also a proud winner in the battle for the charming bride who conquered all the hearts with her beautiful soul and selflessness.”2 Afterwards, the newlyweds went on their honeymoon to Ropsha.

Elena did not find moving to her new home country of Greece easy. She wrote, “The thought of having to leave my home is terrifying, of course, but I am doing my best not to show it to spare Nicky from worrying.”3 The Greek Royal Court was a lot more modest and quiet. Within a year, Elena was pregnant, and her first child – a daughter named Olga – was born on 11 June 1903. Her mother came to Athens to see her first granddaughter. Two more daughters would follow; Elisabeth (born 24 May 1904) and Marina (born 13 December 1906). Elena had nearly died giving birth to Marina, and the couple would have no more children.

Elena and her family would often visit Russia, and rooms were always available for them in the Vladimir Palace. The political turmoil in Greece in 1917 meant that Elena and her family had to leave Greece. For a while, they wandered around Europe as Nicholas’ artistic talents helped them financially. His paintings always sold well. They were able to return to Greece in 1920, but not for long. By 1923, they were living in Paris. Her daughters all made good matches. Olga married Prince Paul of Yugoslavia in 1923, Elisabeth married Count Carl Theodor of Törring-Jettenbach in 1934 and Marina married Prince George, Duke of Kent in 1934.

Elena had not been not particularly close to her sister-in-law Alice (born of Battenberg) as reportedly Elena’s priorities were, “God first, then the Russian Grand Dukes, then the rest.”4 For Elena, an Imperial and Royal Highness, Alice was simply a Battenberg, born a mere Serene Highness and who married up to being a Royal Highness. Alice’s status improved a little in Elena’s eyes when her sister Louise became Crown Princess and later Queen of Sweden and when her son married the future Queen Elizabeth II. They also took Greek lessons together, and both learned to speak the language fluently.

Part two coming soon.

The post Elena Vladimirovna of Russia – A Grande Dame (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 13, 2020

Tsarina – Q&A with author Ellen Alpsten

Tsarina by Ellen Alpsten is a novel of the story of Catherine I of Russia, born a peasant named Marta Helena Skowrońska, who became the mistress and later wife of Peter the Great. After his death, she became the first Empress of Russia in her own right. History of Royal Women got to ask Ellen some questions about her book, and you can find those below!

Tsarina by Ellen Alpsten is available now in the UK and is available for pre-order in the US!

1. How was Catherine influenced by the loss of so many children?

For modern Western women, Catherine I’s plight is unimaginable – in her younger years, she was constantly pregnant and still lived on ferociously, never letting the Tsar out of sight. Also, it seems a paradox that Peter so longed for a son and heir and still extraordinarily little care was taken of her when pregnant – she rode like a soldier and drank like a sailor. Every birth was a gamble of life and death; loving and losing yet another child was always in the cards. I cannot imagine that she ever adopted Peter the Great’s own, stoic stance at this particular subject, who wrote to a friend who had lost a son: “I am so very sorry about your loss of a fine boy, but it is better to let go of the irretrievable rather than recall it; we have a path laid before us, which is known only to God. The child is now in heaven, the place we all want to be, disdaining this inconstant life.’

2. What was Catherine’s relationship like with her daughters?

I have just finished writing the sequel to ‘Tsarina’, a portrait of her daughter Elisabeth’s own journey to hell and back. Elizabeth and her sister Anna had a lonely childhood: they grew up running wild in a vast, dilapidated castle. Later, their aunts Natalya – Peter’s sister – or Praskovia – Tsar Ivan’s V. widow – took care of them. Catherine surely left them behind with a heavy heart, wishing to spend more time with them; yet she had made different choices. The surviving letters by Peter to his daughters are very loving and close, calling them by their nicknames’ Lizenka’ and ‘Anoushka’. Eventually, both girls were made Crown Princesses – Tsesarevny – for lack of a male heir, though they were never meant to rule. Peter saw them as political pawns and mere marriage material. Catherine’s trailblazing seizing of the crown changed the Russian political landscape forever. She also felt for her daughters’ happiness: Only months after Peter the Greats death, she married Anna off in a sumptuous happy feast, ignoring the court’s period of mourning.

3. How did Catherine deal with her husband’s first wife, Eudoxia?

Did she ever meet or see Eudoxia? Possibly during Alexey’s trial, when Peter unleashed a proper witch-hunt in Russia. The meeting taking place in the novel, in the early morning hours of a cold Kremlin corridor, stems from my imagination. Surely, she felt safer once the divorce was through and Eudoxia finally had been bullied into taking the veil, which she had long refused to do. Despite being a bigot, Eudoxia was no pushover, once having thrown a vase at a young Tsar Peter, when he returned from one of his mistresses. Her fate – locked up, her head shorn, in a monastery with a hunchbacked, babbling, tongue-less dwarf as her only companion – certainly served Catherine as a dire warning. She took care to support the Tsar in everything and tried to give him a son and heir.

4. How did Catherine manage to take power?

During her years at the Tsar’s side, she carefully fostered and nurtured relationships – both her female friendships as well as with Peters cronies and companions, be they in the military or court administrators. Peter was incalculable in his ambitions and his anger, and she often softened the blow of his knout – quite literally. When he died, everyone at court owed her. Was this behaviour cunning, or simply her character? Probably a blend of both. She called in favours when the moment of all moments came: Peter the Great died without designating an heir. That is the starting point of my novel.

5. How did Catherine’s upbringing influence her reign?

Growing up as a serf – an unfree peasant attached to the estate of the Russian church in Swedish Livonia (today Estonia and Latvia) – did not allow for airs and graces. Marta, as she was known as a girl, was destined for a life of hard labour from dawn till dusk. When she met Peter aged nineteen or twenty, her character was set, and her stratospheric rise did not change her. She had won Peter with her quick wit, her crude sense of humour – they both adored practical jokes – her level-headedness, her courage and also her soft heart: ‘Nobody can be so evil as for you not find some good in him’, he wrote to her. Peter’s world, too, was harsh, cruel, and lonely. She was his one true companion, an invaluable asset. As Tsarina, she preferred peace and prosperity, as well as a policy of contracts and alliances, to war-mongering.

6. Is there any proof that Catherine II (Catherine the Great) was influenced by the actions of Catherine I?

Catherine II came to Russia as a German Princess, Sophie von Anhalt-Zerbst. She was welcomed into the Orthodox faith and baptised Catherine Alexeyevna in honour of Catherine I., my ‘Tsarina’. She married the heir to the throne, Peter’s and Catherine I’s grandson, living under the watchful and suspicious eye of the Empress Elizabeth, who worshipped her mother. The clever and careful woman that Catherine II was must have taken note of her namesake’s ascent, as ‘Tsarina’ set the scene for all that followed in Russia politically – an unprecedented century of female reign.

The post Tsarina – Q&A with author Ellen Alpsten appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 12, 2020

The Braganzas: The Rise and Fall of the Ruling Dynasties of Portugal and Brazil, 1640–1910 by Malyn Newitt Book Review

The Braganzas ruled the Kingdom of Portugal from 1640 to 1910 and also the Empire of Brazil from 1822 to 1889. The family boasts plenty of interesting characters from child Emperors to mentally ill Queens. Yet, the information in English on them is quite limited, so this book certainly fills a void.

From the introduction to The Braganzas: The Rise and Fall of the Ruling Dynasties of Portugal and Brazil, 1640–1910, I was a little bit apprehensive. For several pages, the author referred to several women only as “the Emperor’s sister” and the like. Luckily, this appears to be just a fluke, and they regain their names in later chapters. The book is quite impressively researched, and I imagine its many pages could turn off some readers. However, I found it very easy to read and not difficult to follow at all. All the family members are treated equally, and the Princesses and Queens are also included, much to my delight.

The Braganzas: The Rise and Fall of the Ruling Dynasties of Portugal and Brazil, 1640–1910 should become a staple of your bookcase if it isn’t already. It is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post The Braganzas: The Rise and Fall of the Ruling Dynasties of Portugal and Brazil, 1640–1910 by Malyn Newitt Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 11, 2020

Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin – “A Grand Duchess to her fingertips”

Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was born on 14 May 1854 as the daughter of Grand Duke Frederick Francis II of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Princess Augusta Reuss of Köstritz. She was just seven years old when her mother died, and her father would go on to marry twice more. His second marriage to Princess Anna of Hesse and by Rhine lasted less than a year as Anna died of puerperal fever after giving birth to a daughter. His third wife was Princess Marie of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, and by her, she became the half-sister of Henry, Prince Consort of the Netherlands.

Marie was baptised on 24 June 1854 in the Golden Hall at Ludwigslust Castle, where she had been born. She spent her childhood at Schwerin Castle and was known as “Miechen” in the family. She was close to her brother Johann Albrecht. At the age of four, Marie was taken in the care of a governess named Clara von Schroeter. Her formal lessons started at the age of six, and she was taught to read, write and count. She learned to sing and play the piano in addition to learning English, French, geography and history. Marie was also close to her paternal grandmother Alexandrine (born of Prussia) whom she would visit three times a week.

Marie would meet her future husband, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia, at military manoeuvres in Berlin. By then, she had already broken her engagement to George, Prince of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. Vladimir wrote to her younger brother, “I liked Duchess Marie very much from the first sight.”1 They soon set their sights on marrying and everything seemed to go according to plan until the matter of religion came up. It wasn’t until 2 May 1874 that they unofficially became engaged as it was finally agreed that she would not have to convert to Russian Orthodoxy.

Marie arrived in St. Petersburg on 27 August 1874 with her father, stepmother and her two brothers. The wedding itself took place on 28 August in the court church of the Winter Palace. Her brothers held a crown over her head during the service. She wore a “white silvery dress, embroidered with flowers, and a diamond tiara on her head.”2 After the wedding, she became known as Maria Pavlovna. The newlyweds moved into the Vladimir Palace on the Neva River, and they also owned a villa in Tsarskoe Selo. Four of their five children would be born in Tsarskoe Selo: Alexander (1875-1877), Kirill (1876-1938), Andrei (1879-1956) and Elena (1882-1957). Only Boris (1877 – 1943) was born in the Vladimir Palace. The death of little Alexander hit Marie hard. The future Alexander III wrote, “In the last few days he contracted pneumonia, and he finally died of heart paralysis. We went to Vladimir and Miechen straight away and found them together with Maman, and the little darling was lying on his mother’s lap as if he was asleep. It is impossible to describe the pain at the sight of my poor brother and his wife.”3 After the birth of their youngest child Elena, Marie became quite ill and was apparently advised not to have any more children.

Marie soon established herself as a great hostess. She would often organise balls and masquerades in the Vladimir Palace. Their court was second only to that of the Emperor. “The Grand Duchess’s Court shone with ladies-in-waiting, who were all equally beautiful, intelligent and cheerful. Marie Pavlovna demanded that all the staff would also look elegant and smart. She would only become closer with those guests who knew how to keep up the conversation and not let it get dull.”4

Marie also became involved with charity such as the Imperial Women’s Patriotic Society (IWPS). She and her husband were also honorary members of several charities.

In 1894, Vladimir’s brother Alexander III died and was succeeded by their nephew, now Nicholas II. He married Alix of Hesse (Alexandra Feodorovna) shortly after his accession and she and Marie could not have been any more different. While Alexandra was never quite popular, and Marie was the centre of attention wherever she went. The relationship between Nicholas and the rest of the family visibly deteriorated over time. This came to a head when Marie’s eldest son Kirill married the divorcee Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who was also his first cousin. Nicholas was against the match and refused to sanction it. He resigned all his commissions, and he was banished from Russia. From then on, Vladimir and Marie also began to spend much of their time abroad.

On 17 February 1909, Marie’s husband died of cerebral oedema at the Vladimir Palace. It was only then that Kirill was pardoned and allowed to return to Russia. Marie gave the governor of St Petersburg 5,000 roubles to give out as alms in her husband’s memory. Their shared grief brought Marie and her sister-in-law Maria Feodorovna closer together.

During the First War World, Marie became involved in helping the army, and she went on to assist in military hospitals and infirmaries. She funded a hospital train which was designed to help evacuate the wounded. As time went on, the situation in Russia deteriorated, and Marie believed that the monarchy was at risk. The murder of Rasputin only deepened the rift that now existed in the Imperial Family. On 15 March 1917, Nicholas abdicated the throne. He nominated his brother Michael to succeed him, but he declined, and the Romanov dynasty came to an end. Next in line to the defunct throne was Marie’s son Kirill.

Marie was put under house arrest in December 1917 while she was in Kislovodsk. On 31 December 1919, Marie became one of the last Romanovs to escape from Russia. She was met by her niece Olga who wrote, “I was amazed that she arrived in the city on her own train, accompanied by the retinue and remained a Grand Duchess to her fingertips. There was never a particularly loving relationship between aunt Miechen and our family, but I felt proud for her. Despite the danger and hardships, she firmly adhered to the traditions of the past era of splendour and glory.”5

At Cannes, she was finally able to rest after a long journey. She then went to Switzerland, where her daughter Elena was, and they finally saw each other again for the first time in five years. By then, Marie was already suffering from kidney problems and various other ailments. She would spend the last months of her life in Contrexéville in France. She took the waters there but they could nothing for her anymore. She died on 6 September 1920 at the Hotel La Souveraine. She was buried in an Orthodox chapel she had built in Contrexéville – she had finally converted to Russian Orthodoxy later in life.

In 1924, her son assumed the empty title of Emperor, and his descendants still claim the Russian throne today.

The post Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin – “A Grand Duchess to her fingertips” appeared first on History of Royal Women.