Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 174

July 13, 2020

Marie of Württemberg – Prince Albert’s stepmother (Part two)

In the early years of the marriage, Marie suffered at least two miscarriages that reportedly almost cost her her life, after which she travelled to the waters at Travemünde. She wrote to her husband, “The two miscarriages so quickly following each other have deeply affected my health and body and requires the use of the waters. First to help strengthen the nerves and secondly to achieve hope for the future, to become the mother of a healthy child, if God wills it!”1 Unfortunately, Marie’s wish would never come true. As Duchess, Marie had supported the founding of two schools for girls. She was also a patron of the arts and was an acquaintance of Franz Liszt.

On 10 February 1840, Prince Albert married Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and so Marie became the stepmother-in-law of the British Queen. Marie and Ernst had both been invited to Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838 but Marie did not go. Albert wrote to his stepmother after becoming engaged to Victoria and also during the days leading up to the wedding. He wrote, “The farewell in Gotha was quite sad for me and I haven’t been very cheerful since then because the last events in England don’t agree with me. People behave quite miserably on all sides towards me…”2 After the wedding, he wrote asking for her blessing but it is unclear why she wasn’t at the wedding itself. When the future King Edward VII was born in 1841, he asked Marie to become a godmother. She agreed but did not attend the christening and Victoria’s mother acted as her proxy. Albert had even specifically written to her that, “You should not be afraid of appearing in person as a proxy can be quite useful.”3

In 1842, the younger Ernst married Alexandrine of Baden, giving Marie another step-daughter-in-law. But while Victoria and Albert would go on to have nine children, the union between Ernst and Alexandrine would remain childless, probably due to Ernst’s venereal disease.

On 29 February 1844, Marie was widowed when Ernst died at the age of 60. She wrote to Albert, “The poor, good Duke, dear unhappy child, is no longer. […] Suddenly when he got up out of bed, he felt so tired and completely lacking in strength and at half-past six he passed away after asking for help with great haste and saying, ‘Oh I can’t take it’, and it was over without great agony and great pain.”4 Marie was no longer the wife of the reigning Duke and as the Dowager Duchess she chose to live at several residences in the duchy, Schloss Reinhardsbrunn, Schloss Friedrichsthal, and Schloss Friedenstein. It took quite a while to establish her rights, and she even had to ask Alexandrine to intercede with Ernst on her behalf.

As Albert’s family grew, Marie kept in touch with them too. She wrote to the Prince of Wales on the occasion of his confirmation and he wrote back, calling her “Grandmama.” She met her step-granddaughter Victoria shortly after her marriage in 1858 and Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter asking her if she found “Grandmama looking so old.”5 She also corresponded with Princess Alice quite regularly.

By July 1860, Marie was clearly ill as Albert wrote how “unhappy it makes me to hear that you have suffering so!”6 Albert’s last letter to his stepmother is dated 13 September 1860 and comes with his congratulations for her birthday three days later. He adds, “I was pleased to hear that you have been doing much better in the past few days.”78

One of Marie’s last letters was to her stepdaughter-in-law Alexandrine and was dictated to Julie von Wangenheim. “Albert gave me a wonderful wheelchair, which unfortunately I can no longer do without in the parlour, so much for walking; it is an English masterpiece!”9 Unfortunately, Marie would die just three days later on 24 September 1860. She had been suffering from erysipelas with high fevers and “the most terrible pain.” She had passed away after a night of struggling to breathe with “the expression of peace.”10

Her last wishes were written down, “Dear loved ones, the devoted will accompany me to my final resting place, even my good servants will not me go but I forbid anyone to accompany me who is suffering or unwell. There should be as little effort as possible for my funeral. My coffin should be simple, my clothes white muslin, simple morning hats that I always wear so that no hair can be seen. A head pillow with white oats with lace I have made. I wish to rest under God’s open sky, but I want to submit to the wishes of my relatives.”11

She was buried in the Ducal mausoleum at the cemetery on the Glockenberg in Coburg.

The post Marie of Württemberg – Prince Albert’s stepmother (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 12, 2020

Marie of Württemberg – Prince Albert’s stepmother (Part one)

Marie of Württemberg was born on 17 September 1799 in Coburg as the daughter of Duke Alexander of Württemberg and Antoinette of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. She was the eldest of five children, though two of her brothers would die in infancy. Two brothers named Alexander and Ernest would live to adulthood. Her mother was the sister of the Duchess of Kent, King Leopold I of the Belgians and Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Her father’s sister was Sophie Dorothea, wife of Tsar Paul I of Russia.

Marie spent most of her childhood at Schloss Fantaisie in Bayreuth, which her father had inherited from his mother in 1798. She also spent some time in Russia as her father was a Lieutenant General in the Imperial Russian Army. Not much is known of her early youth. In 1819, Marie joined her parents and brothers for a long trip. They went mostly around Germany, Austria and Russia to visit relatives. In early April 1820, they also attended the wedding of King William I of Württemberg and his first cousin Pauline of Württemberg. Marie especially enjoyed her visit to Vienna, describing it as “unabashed happiness.”1 She also loved music, feeling right at home with the Wiener Walz. Francis I, Emperor of Austria, had been married to Marie’s aunt Elisabeth but she had tragically died in childbirth in 1790, but the Württembergs were still considered family in Austria. Marie wrote of all her experiences to her best friend Charlotte of Prussia, wife of the future Nicholas I of Russia. She also remained in touch with her cousin Pauline after her wedding.

In Coburg in July 1819, Marie even met the woman she would one day replace as Duchess, Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg. Louise was by then heavily pregnant with . Marie noted Louise’s charm and naturalness. In August 1819, Charlotte gave birth to a daughter named Maria. Marie wrote to her, “I cannot tell you how happy I was when I found out that heaven had given you a little princess. […] May God give health to the beautiful mother and her dear newborn child; this wish is sincere, believe it, dear Charlotte.”2

Marie lost her mother on 14 March 1824 and she had been just 44 years old. She was ill for only a short period of time, and Marie described the painful illness to her uncle Ferdinand in Vienna. She wrote, “At around 5 o’clock I went into her room for the last time, kissed her cold hand. […] Around 10 o’clock, dear uncle, the angelic mother was no more. She died like an angel; her death was so gentle and edifying. I cannot write any more today.”3 Her mother had died in St Petersburg, and for now Marie remained there. Meanwhile, in Coburg, her uncle Ernst’s marriage to Louise had fallen apart, and they were divorced in 1826. Louise would die of uterine cancer on 30 August 1831.

Her uncle Ernst had already officially asked Marie’s father for his permission to marry her on 2 May 1830. He happily wrote to her that he hoped his boys would find a “real, true mother”4 in her. Unfortunately, Marie also fell ill during this time, and she was not able to write to her betrothed again until October. “You must be mad at me again, but this time I am completely innocent. My weakness hardly allows me to write these lines. You are the first one to whom I write after my long-drawn-out illness. Very seriously ill from a violent biliary fever, I was sick for over a month.”5

The 33-year-old Marie married her 48-year-old uncle on 23 December 1832 in Coburg and Marie became the stepmother of his young sons, the future Ernst II and Prince Albert. The boys longed for a mother, and the younger Ernst wrote to her in April 1833, “Dear Mama, I was very happy when I heard you had arrived in Gotha quite happy and well.[…] We live in the constant sweet hope of having you close to us again.”6

Just seven months after the wedding, Marie suddenly lost her father. Marie had been summoned to Gotha, and young Ernst wrote to her there, “Hope alone remains with us; it doesn’t leave us, and we are in pain over your father’s illness.[..] Hurry back to us soon.”7 Three days after young Ernst’s letter, Marie’s father died at the age of 62. The court went into mourning for three months. As the boys grew up, they regularly wrote to Marie.

Part two coming soon.

The post Marie of Württemberg – Prince Albert’s stepmother (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 9, 2020

Maria Isabel of Braganza – An obstetric tragedy

Maria Isabel of Braganza was born on 19 May 1797 as the daughter of John VI of Portugal and his wife Carlota Joaquina of Spain. She was their third child, but her elder brother would die at the age of six. Six more siblings would follow, including Peter IV of Portugal and I of Brazil. Her parents’ marriage was notoriously bad, and her mother even attempted to have her father declared insane, as her grandmother Queen Maria I had been. Nevertheless, it is said that the couple remained cordial towards their children.

In 1807, the family was forced to flee to Brazil as Napoleon invaded Portugal. Carlota sent her eldest surviving son to join his father and grandmother on board the Principe Real while she and the other children boarded the Affonso d’Albuquerque. The arrival at Rio de Janeiro was pitiful. Carlota and her children had been compelled to shave their heads and wore white muslin caps as they entered the harbour. At least they were free from the clutches of Napoleon. The family continued to live apart while in exile. Carlota adored her second surviving son Miguel, who lived with her. She and her husband communicated through letters and hardly saw each other for the next four years.

During this time in Brazil, Maria Isabel was carefully educated under the supervision of her mother in a liberal atmosphere. She was known to be balanced, kind and introverted and resembled her father personality-wise.

On 20 March 1816, Queen Maria I died, and Maria Isabel’s father became King of Portugal and Brazil. On 29 September 1816, Maria Isabel married her widowed maternal uncle King Ferdinand VII of Spain. He was 13 years her senior and his first wife Maria Antonia of Naples and Sicily had died in 1806 without having had any children, but she had suffered at least two miscarriages.

(public domain)

(public domain)Maria Isabel fell pregnant quite quickly and gave birth to a daughter on 21 August 1817. Little María Luisa Isabel died at the age of four months on 9 January 1818. Maria Isabel became pregnant again not much later and went into labour on 26 December 1818. The baby was in a breech position, and the doctors soon realised that the child had died. Maria Isabel was thought to be dead as well. The doctors then began to perform a caesarian section to remove the dead fetus. She was revived by the pain and would die a few hours later in great pain.1 “When they extracted the girl that she carried in her womb, she was born lifeless, the mother gave such a cry that she was not dead yet, as the doctors believed, which made it a dreadful butchery.”2

As she did not leave an heir for the throne, she was buried in the Pantheon of the Princes, rather than the Pantheon of the Kings, in the El Escorial monastery.

During her short tenure as Queen, Maria Isabel did manage to leave a legacy behind. She promoted the creation of the Royal Museum of Paintings, now known as the Prado museum. Her most famous painting shows her pointing towards the museum. The painting was made on her widower’s orders around ten years after her death. Her husband would go on to marry two more times. His fourth and final wife Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies gave him two daughters, and the eldest succeeded him as Queen Isabella II of Spain.

The post Maria Isabel of Braganza – An obstetric tragedy appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 8, 2020

Anne Boleyn: 500 Years of Lies by Hayley Nolan Book Review

Anne Boleyn, the second wife of King Henry VIII, remains one of the most controversial and interesting women in history. She was one of the reasons I began my website, and I remember reading everything I could.

Anne Boleyn: 500 Years of Lies begins with the tale that she must be most maligned women in history, and Hayley Nolan is here to tell you the truth. I must have been reading the wrong books because I’ve read plenty that were not biased against Anne. This book is clearly aimed at a younger audience with its clickbaity title and hashtags. The angry tone of the author is a huge turn-off, and I often found myself rolling my eyes. For me, it was a complete distraction of what could have been a good book about Anne.

Honestly, there are better books out there about Anne. I can recommend The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England’s Most Notorious Queen by Susan Bordo (US & UK), for example.

Anne Boleyn: 500 Years of Lies by Hayley Nolan is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Anne Boleyn: 500 Years of Lies by Hayley Nolan Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 7, 2020

Ingeborg Magnusdotter of Sweden – A tragic motherhood

Ingeborg Magnusdotter of Sweden was born circa 1277 as the eldest child of King Magnus III of Sweden and Helwig of Holstein. She would be one of at least five siblings. Her younger brother Birger succeeded their father as King of Sweden.

Not much is known about her youth, but by 1288, she was betrothed to King Eric VI of Denmark. The wedding took place in Helsingborg in 1296, making Ingeborg Queen of Denmark. In a double alliance, her brother Birger married Eric’s sister Martha.

She probably played no role in the politics of her time and could only helplessly watch as the situation in the country of her birth spiralled out of control. Her other two younger brothers were imprisoned by King Birger, and both starved to death during their imprisonment. They had been arrested during King Birger’s Christmas celebration, known as the Nyköping Banquet. A subsequent rebellion forced Birger, Martha and their son into exile in Denmark, where they were received by Ingeborg.

Ingeborg and Eric had many children together, estimated to up to 14, though none would survive to adulthood. One tragic story tells us that after Ingeborg had given birth to a healthy son, she proudly showed him off to the people from her carriage. However, he fell from her grip when the carriage suddenly moved, and he broke his neck and died.

Shortly after this, Ingeborg entered the St. Catherine’s Priory in Roskilde. Some say she went voluntarily out of grief for the death of her son and the deaths of her brothers. Others say she was forced into retirement by her husband. In any case, Ingeborg had been a benefactor of the priory before she came there.

She died not long after entering the priory – on 15 August 1319. She was buried in St. Bendt’s Church at Ringsted, and her grave has the inscription, “I, Ingeborg of Sweden, once queen of Denmark, ask for forgiveness from anyone to whom I may have caused sorrow, to be please to forgive me and to remember my soul. I died in the year of Our Lord 1319.”1 Her husband would die a few months after her.

The post Ingeborg Magnusdotter of Sweden – A tragic motherhood appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 6, 2020

Princess gowns – Jørgen Bender’s creations for Princess Benedikte of Denmark

This summer, the Gala Hall at the Christian VIII’s Palace in Copenhagen will play host to an exhibition of royal gala gowns created by Jørgen Bender for Her Royal Highness Princess Benedikte of Denmark. Princess Benedikte lives in the east wing of the Palace.

Jørgen Bender was an influential dressmaker for the Danish Royal House for four decades. He not only designed dresses for Princess Benedikte but also for her mother Queen Ingrid and her sisters Queen Margrethe II of Denmark and Queen Anne-Marie of Greece. The exhibition focusses on the bond between Princess Benedikte and Jørgen Bender.

Click to view slideshow.

Museum Director Thomas Thulstrup said, “The exhibition is a marking of the Princess’ sharp eye for quality and craftsmanship. She has always supported Danish and sustainable design, which is right in line with Bender’s design aesthetics. It is, therefore, a great honour for The Royal Danish Collection to exhibit a collection of exclusive creations from Jørgen Bender.”

“Like Blom, Bender was incredibly conscious of quality when it came to textile and models, a master at draping and a true artist”, Princess Benedikte said. He also often remade gowns for a certain occasion. “Jørgen Bender has changed countless of my gowns, a form of recycling, one might say. Often he would also create two versions of a gown, one for summer and one for winter.”

The exhibition will run from 4 July until 30 August 2020. Read more here.

The post Princess gowns – Jørgen Bender’s creations for Princess Benedikte of Denmark appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 5, 2020

Marie of the Netherlands – A Dutch heart (Part two)

The newlyweds moved to Neuwied, but they also often returned to Wassenaar. Just 11 months after the wedding, Marie gave birth to her first child – a son named William Frederick. Her father visited Neuwied shortly after and held his grandson. He even renovated his own estate to include a new wing with study for his son-in-law and a playroom for his grandchildren. Marie and William went on to have five more children together: Alexander (1874 – 1877), William (1876 – 1945), Victor (1877 – 1946), Louise (1880 – 1965) and Elisabeth (1883 – 1938). Marie remained popular in the Netherlands, and the family spent a lot of time there. William and the children learned to speak Dutch and were considered members of the extended Dutch Royal Family.

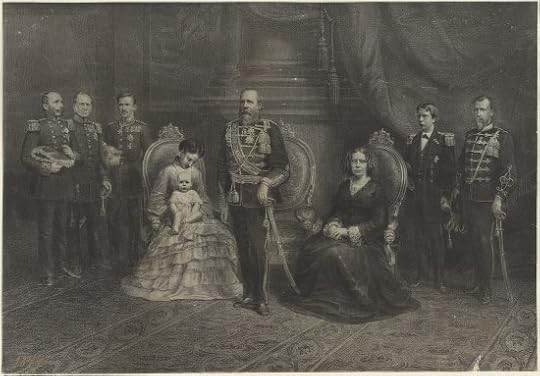

(public domain – RP-P-OB-105.647 Rijkmuseum) From L-R: Prince Henry, Prince Frederick, William, Prince of Wied, Marie with her son William Frederick, King William III, Queen Sophie, Prince Alexander and Prince William

(public domain – RP-P-OB-105.647 Rijkmuseum) From L-R: Prince Henry, Prince Frederick, William, Prince of Wied, Marie with her son William Frederick, King William III, Queen Sophie, Prince Alexander and Prince WilliamIn 1877, Marie was in The Hague when Queen Sophie passed away. Marie and her father were in the room next to Sophie’s when King William III came to see her. A report stated, “He found the Queen deadly weak and almost dying, the sufferer spoke with a bland voice a few words of no meaning. The King stayed no more than a few minutes in the sickroom and then went to the next room where Prince Frederick and the Princess zu Wied were. Here he began speaking of the Queen in such an inappropriate manner that the Princess zu Wied got up and left the room in tears.”1 Her thoughts on William’s subsequent marriage to Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont and the birth of their daughter Wilhelmina are not known, but she continued to visit the Netherlands.

(public domain)

(public domain)In early September 1881, Marie’s father was preparing to travel to Neuwied when he came down with a cold. On 5 September, he returned to De Paauw with a fever and took to his bed. Marie received a telegram and hurried home to be with her father. She and Marie of Prussia (wife of Prince Henry – King William II’s third son) stayed up all night by his bedside. On the morning of 8 September, Frederick sat down in his armchair to say goodbye to everyone. He died that night at half-past 10. As a woman, Marie could not attend his funeral, but her husband was there on her behalf. He had reached the grand age of 84. His last public appearance had been at the baptism of the future Queen Wilhelmina.

Wilhelmina first mentioned Marie to her governess Miss Winter in 1891 in a telegram when Marie, William and their daughters Louise and Elisabeth were staying at the Loo Palace. Wilhelmina referred to them collectively as the “Wieds.’2 Miss Winter later came to work for Marie to teach her daughters English.

Queen Emma wrote to Miss Winter, “They would wish you to teach the girls English (I suppose including literature) & to be a pleasant companion not only for the girls but for the whole home party. I asked what would be your duties & got this answer: to feel happy & at home with us and teach the girls English. You would not have any grave responsibilities because Miss v. Harbon (the daughters’ governess) is still with the girls & in charge of their education. You know enough about the life of the Wieds to realise that you would form one of the home circle and enjoy family life. You also know that they spend the summer and autumn at Monrepos in Neuwied & the winter in Italy at St Margarita. The Wieds offer you 100 marks (hundred!) a month & of course would pay your travelling expenses coming & leaving.”3

After the death of Sophie, Grand Duchess of Saxe-Weimar – a daughter of King William II – Marie was one of the last remaining family members of Queen Wilhelmina. She and her husband were present at Wilhelmina inauguration in 1898. She was also present for Wilhelmina’s marriage to Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1901, and she was one of Princess Juliana‘s godparents in 1909. When Marie’s eldest son William Frederick married Princess Pauline of Württemberg – a first cousin of Wilhelmina through her mother Emma – both Queen Emma and Queen Wilhelmina were present. When Marie and William celebrated their silver wedding anniversary, the two Queens gave them two paintings by Mesdag.

In 1899, Marie became a grandmother for the first time with the birth of Hermann, Hereditary Prince of Wied. A second grandson named Dietrich was born in 1901. Her second surviving son William married Princess Sophie of Schönburg-Waldenburg in 1906, but she would not live to see him elected Prince of Albania. Marie was widowed when her husband died on 22 October 1907 after a brief illness. He was 62 years old.

Marie and her daughters Louise and Elisabeth withdrew to villa Waldheim at Monrepos. She lived to see the birth of her granddaughter, Marie Eleonore of Wied, by her son Willliam in early 1909. Marie herself died quite suddenly on 22 June 1910, several weeks before her 71st birthday. She had developed a fever only a day before. Dutch newspapers reported that Marie “despite living for 40 years abroad had not lost her Dutch heart, but has maintained her love and sympathy for the Dutch people to the fullest as she had also shown. That love and sympathy have always been reciprocated by the Dutch people with warmth.”4 The Dutch court went into mourning as well, and flags were flown at half-mast.

Queen Wilhelmina was represented by her husband, Prince Henry, at the funeral in Neuwied. She was buried at the family cemetery near the castle. The castle was demolished in the ’60s. While her two daughters never married, her third surviving son married Countess Gisela of Solms-Widenfels in 1912. The current Prince of Wied is her great-great-great-grandson.

The post Marie of the Netherlands – A Dutch heart (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 4, 2020

Marie of the Netherlands – A Dutch heart (Part one)

Princess Marie of the Netherlands was born on 5 July 1841 as the daughter of Prince Frederick of the Netherlands, second son of King William I of the Netherlands, and his wife and first cousin Princess Louise of Prussia. She was born on her parents’ estate of Huize (House) De Paauw in Wassenaar near The Hague. She would be the youngest of their four children. Her elder siblings were Louise (born 1828), William (born 1833 – died in infancy) and Frederick (born 1836 – died in childhood).

Marie was known as Mené in the family. The two sisters were taught French, German and a little bit of English and Russian. They also practised their painting, needlework and maths. They were given instruction in music by the director of the The Hague music school.1 Frederick had been unhappy with the way his nephews were being raised and was looking for a more conservative tutor for his own son. He found one in Major Ernest van Löben Sels.2 Marie’s first governess was her sister’s former English teacher Maayke Petronella à Lavoine, followed by Jacoba Cecilia van Door, the daughter of the court marshall. Tragedy struck in 1846 when the 10-year-old Frederick fell during a gymnastic exercise. He died ten days later.

Sophie of Württemberg, wife of the future King William III, wrote, “I am deeply saddened. The poor Prince Frederick has lost his only son. He died this morning after being ill for over a week, ten years old. With him, the future of the Prince is destroyed – everything he has gained, built, the ties with this country – everything is gone. He is desperate. She is very controlled, I would say – cold. But I think she is hiding her grief. During the illness of his son, Prince Frederick aged a lot, that’s how much it affected him. The child was the apple of his eye, not very sweet but still intelligent and promising. Saturday. After writing the above, yesterday, I went to see Prince Frederick and his wife. They took me to the little body. I had never seen a dead child before, it is awful. […] Frederick sobbed like a little child and said, ‘There is all my love, it is over now.'”3 The devastated parents kept the boy’s room as it was.

In 1850, Louise married the future King Charles XV of Sweden, leaving Marie as the only child at home. She had been just four years old when Frederick died and only 9 when her sister married. She essentially grew up as an only child. Marie was diagnosed with profound hearing loss from an early age, but she was known to be especially cheery and happy. Shortly after her confirmation in 1858, her parents began looking for a husband for her. Several candidates were considered, such as Frederick Francis II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, who was widowed in 1862 and Prince Albert of Prussia – her first cousin through Princess Marianne of the Netherlands. She was even briefly considered for the future King Edward VII before being vetoed as “too plain” by Queen Victoria.4 In any case, none of those matches went anywhere. Despite her enormous wealth, Marie was not known to be beautiful, and Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter described her as an “ugly monkey”5, though she liked her.6 Marie spent the following years travelling around with her mother to various spas.

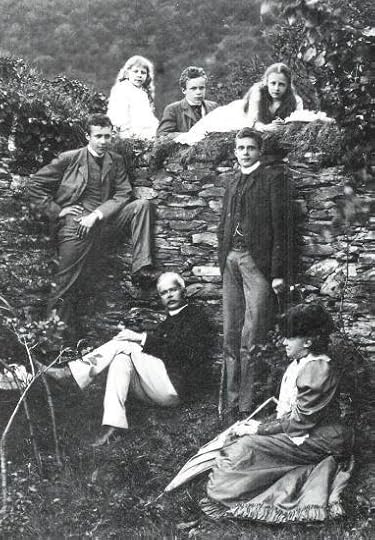

In the summer of 1869, Marie received an offer of marriage from William, Prince of Wied. She was by then 28 years old, and he was four years younger. William no longer had any actual land to rule, as his principality of Wied had been annexed by Prussia. There were soon rumours that Marie’s father thought very little of his future son-in-law as he hoped for a Crown Prince for Marie as well. William was distantly related to the Dutch royal family (as a descendant of Carolina of Orange-Nassau), and his uncle would eventually succeed King William III of the Netherlands as Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

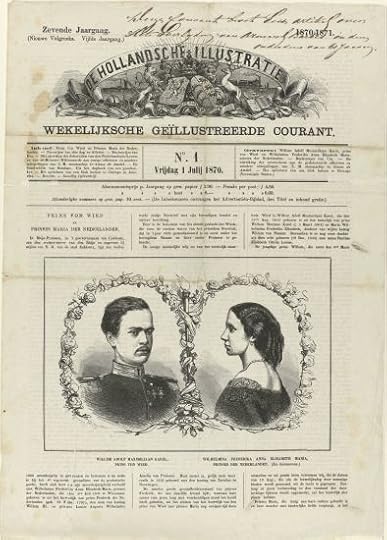

Article about the engagement (RP-P-OB-105.363 Rijksmuseum)

Article about the engagement (RP-P-OB-105.363 Rijksmuseum)The engagement was celebrated on 8 December 1869, followed by the approval of parliament on 20 December. The actual wedding was postponed twice – once by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War as William was a serving officer in the Prussian army – and the second time by the deaths of Marie’s mother and sister. They were finally married on 18 July 1871 in Wassenaar in the village church. Reports of the wedding tell us that the preacher – invited for a brief wedding speech – launched into an endless sermon with Marie becoming paler and paler as it went on. The wedding breakfast took place on her father’s estate, followed by a reception. Marie proudly showed off her dress, and the many jewels she was wearing. By eight in the evening, the situation became a bit awkward as – per protocol – the King should be the first to leave. However, Queen Sophie had left first, and William had to wait for the carriage to return to pick him up. Nevertheless, it had been a grand wedding.

The post Marie of the Netherlands – A Dutch heart (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 2, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of Prince Henry

Born Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin on 19 April 1876 as the youngest son of Frederick Francis II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and his third wife, Princess Marie of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, he became Prince Consort of the Netherlands as the husband of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands.

Although their marriage was happy at first, over time, the couple drifted apart. Their only surviving child, the future Queen Juliana, was the apple of her father’s eye.

Henry’s death came rather sudden though his health had been declining for some years. He had suffered his first heart attack in 1929. On 28 June 1934, he arrived at the office of the Red Cross in Amsterdam in the early morning. Just before ten, he suffered another heart attack. He was brought to Noordeinde Palace in The Hague by ambulance as Queen Wilhelmina was informed of his condition. Their daughter Juliana was away in England at the time. He seemed to recover but suffered another heart attack on 3 July. Wilhelmina had been away to a lunch and arrived back when he had already passed away. Wilhelmina herself informed her daughter in England and later told a courtier that her daughter had been calm. “We are brave people, who don’t wail.”1 Later that day, Queen Wilhelmina made the official announcement: “It has pleased God to call my beloved husband to him. This afternoon, he passed away calmly but suddenly. I announce this with the greatest sadness. I am convinced you will share in mine and my daughter’s sorrow.”2

Juliana had the firm belief that death was simply the start of something else, and she wrote, “Mother carefully told me today that Father had died – I long to go to her. Although, after Grandmother’s death, death means nothing more to me than lovely things and I know Mother feels that as well. Father was very cheery this morning, and it happened in a second, not in her presence. Isn’t it lovely, so sudden. I am so glad to know that ever since Grandmother died, every life ends happily by ‘death.’ I am becoming a philosopher – don’t mind me.”3

Juliana took the night boat to Hook of Holland, and Wilhelmina was there to pick her up when she arrived in the morning. Juliana made sure the rings he had worn were put back on his fingers and had his favourite Huguenot cross put around his neck. She also put a bouquet of red roses in his coffin. She also requested her father’s favourite clock with little horseheads from the Loo Palace and had it put into her own room.

In her memoirs, Wilhelmina wrote, “Long before he died my husband and I had discussed the meaning of death and the eternal Life that follows it. We both had the certainty of faith that death is the beginning of Life, and therefore had promised each other that we would have white funerals. This agreement was now observed. Hendrik’s white funeral, as his last gesture to the nation, made a profound impression and set many people thinking.[…]The story of my life would become much too long if I tried to express what these two lives4 which were cut off so shortly after one another have meant to Juliana and me. After the funeral, we went to Norway to rest and to recover, and stayed there for six weeks.”5

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of Prince Henry appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 1, 2020

Uncrowned Queen: The Fateful Life of Margaret Beaufort by Nicola Tallis Book Review

Lady Margaret Beaufort was born on 31 May 1443 at Bletso as the daughter of Margaret Beauchamp and John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. Her father was the second son of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, the eldest son of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster by his mistress and later his wife, Katherine Swynford. Margaret would never know her father. He died on 27 May 1444, leaving Margaret a wealthy heiress.

A first marriage at a very early age was dissolved, and Margaret never considered it a real marriage. At the age of 12, she was married again to Edmund Tudor, the half-brother of King Henry VI. He was 24 years old, and Margaret became pregnant almost immediately. Edmund never lived to see the birth of his child. He died on 1 November 1456 of the plague. On 28 January 1457, still only 13 years old, Margaret gave birth to her only child, a son – the future Henry VII.

Much has been written in fiction about Margaret’s supposed scheming to get her son on the throne, leaving her with a brutal reputation that has even included the murder of the Princes in the Tower.

Nicola Tallis attempts to piece back Margaret’s reputation to something resembling the truth, which is not an easy thing to do. Nevertheless, Nicola Tallis succeeds and brings back Margaret to her rightful place in history. As a fan of Nicola’s previous book about Lady Jane Grey (Crown of Blood), I had honestly expected nothing less. A highly recommended read for all Tudor lovers.

Uncrowned Queen: The Fateful Life of Margaret Beaufort by Nicola Tallis is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Uncrowned Queen: The Fateful Life of Margaret Beaufort by Nicola Tallis Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.