Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 172

August 2, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Neutrality and the First World War

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie were assassinated in Sarajevo. The event has gone down in history as the kickstarter of the Great War. However, at the time, not all of Europe’s royals were that concerned. Emperor Wilhelm II continued to sail around Norway, and Queen Wilhelmina continued to pose for a portrait with Henry and Juliana for Thérèse Schwartze in the scorching heat.

On 28 July 1914, Austria declared war on Serbia and Russia began a general mobilisation two days later. The Netherlands began mobilisation on 31 July. On 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia, followed by France and Belgium a few days later. Belgium had declared their neutrality, which was violated, bringing England in the mix – which then declared war on Germany on 4 August. However, the Dutch government was informed by Germany on 3 August that it would respect the neutrality of the Netherlands. Yet, the fighting in Belgium brought the war awfully close and both German and Belgian wounded soldiers were being treated in the Netherlands. The war violence also brought around 340,000 Belgian refugees to the Netherlands.

Of the neutrality, Wilhelmina wrote in her memoirs, “Neutrality in the sense in which it is used in international law does not simply mean that one stands aloof. It is a defined legal status which the neutral country has adopted, and the parties at war are obliged to respect its rights. The duties of neutrality are absolute and leave no room for human feelings. The situation can easily lead to tensions and struggles in the individual. At heart, man is never neutral, he always has a preference, sometimes without knowing it; and in a world-wide conflict, more than ever, his feelings are constantly involved, and his preference is reinforced.”1

With the continued threat of the neutrality being violated, life for Wilhelmina changed dramatically. Festivities and ceremonies were cancelled, and shortages of things like coal became the norm. If Wilhelmina travelled at all, it was to places where disasters had taken place. In 1916, she visited areas that had been flooded. In May 1917, she visited the province of Drenthe after a peat fire which killed 16 people. She also made military inspections and was heavily involved in a committee that was meant to help with economic needs. She made several personal donations to the committee as well.

Wilhelmina later wrote in her memoirs, “The war suddenly imposed upon me the obligation to try and provide such leadership, or rather to let it proceed from me. I was fully aware that this could only be done once a new confidence in me had been created. A war makes special demands in this respect; the confidence that was sufficient in peacetime is no longer enough. Confidence was the word that echoed in me constantly; my thinking and acting were long dominated by the thought that I had to earn it. From morning till night, this idea never left me. At such moments one becomes conscious of the smallness of one’s powers, and one realises acutely one’s dependence on God’s help.”2

Wilhelmina also wrote, “My first duty was to be ready at all times. Everything was governed by it. This thought occupied me constantly and often worried me unnecessarily. I had to keep up this state of readiness till the end of the war, for on no account could I afford to be surprised by a major crisis at a moment when I was not in a state to take (make?) important decisions.[…] My love for the fatherland was like a consuming fire, and not only in me; it expressed itself in fierceness around me. It was only restricted by reflection and reason when the highest interests of people and the country demanded it. Anyone who threatened to damage these interests was my personal enemy. My thinking and my whole life was dominated by vigilance on their behalf.”3

The personal German connections during the war were a bit more difficult. Both Queen Emma and Prince Henry were German and had extended family living in Germany. Queen Emma’s half-brother Prince Wolrad was killed during the war in October 1914. On the other hand, Emma’s sister Helena had married into the British Royal Family. Wilhelmina wrote in her memoirs, “Mother, who had taken up her residence at the Voorhout, spent the whole of the war in town so as to be immediately informed of the news and have daily contacts with us. She shared fully in my anxiety for the nation. She also had private worries concerning her relatives. One of her sisters lived in England, the widow of the Duke of Albany. Mother’s thoughts often went out to her. Her other relatives lived in Germany. From a distance, she continued to give them her warm and loving sympathy.”4

At the end of the war, the German monarchies came to an end. Queen Wilhelmina was most surprised to find the German Emperor looking for her help. On 10 November 1918, Wilhelm and his entourage appeared at a border post at Eijsden where he was denied entry. As Wilhelm paced around the train station of Eijsden, Wilhelmina was informed of the situation. She later wrote, “I shall never forget the November morning at the Ruygenshoek when I was called very early with the news that the Kaiser had crossed our frontier in the province of Limburg. This communication from the government was soon followed by a telegram from the Kaiser himself, who tried to explain his action to me. I was utterly astonished; it was the very last thing I should have thought possible.[…] The Netherlands government assigned him a place of residence and demanded a promise that he would not leave it and would abstain from political activity. His abdication followed soon after.5

She added, “The flight and abdication of the Kaiser were followed by the abdication of the other German princes. Everything happened with incredible rapidity. Revolutionary elements and excited crowds demanded the abdication of their princes. The weaker ones gave in at once and left their lands precipitately; some other complied with greater dignity. Of course, they carried all the members of their families with them in their fall; none of them would be allowed to hold any public office. Even those who devoted the whole of their lives to the service of their peoples and who were held in the highest esteem were committed to the bitter fate of the outcast. In the meantime, the Allied victory had been gained and a cease-fire agreed upon. The armistice was then signed, and subsequently, the peace was dictated to Germany.6

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Neutrality and the First World War appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 1, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The life of Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont (Part one)

Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont was born on 2 August 1858 as the daughter of Georg Viktor, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, and Princess Helena of Nassau. She was their fourth daughter, and she would also have two younger sisters and a brother. After her mother’s death in 1888, her father remarried to Princess Louise of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, and from that marriage, Emma also had a half-brother.

Emma and her sisters were raised by an English governess who taught her drawing and embroidery and French literature. She also had history lessons and learned to speak French, which would come in handy later on as her future husband did not speak German. The family also spent a lot of time travelling around Italy, England, Scandinavia and France.1 Despite being from a small principality, the family was well-connected. Emma’s aunt Sofia was Queen of Sweden and Norway. Another aunt was Duchess of Oldenberg and her uncle Adolphe would eventually become Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

Emma’s daughter later wrote in her memoirs about her mother’s youth, “As a young girl Mother enjoyed painting and drawing and had art lessons. I still possess a few of her old sketch-books. She always showed a lively interest in the arts and continued working with the etching-needle to an advanced age. She had a good feeling for line; her favourite subjects were flowers. Her maturity at an early age is indicated by a letter I possess, written when she was about ten years old; it is a letter about practical matters, which my grandmother had told her to write. While she was living with her parents, she acquired an understanding of ordinary life which was very useful to her later on. She had an advantage over me in that respect; compelled to live in a cage by a convention which was inexorable in those days, I never had the opportunity to see ‘normal life’ as a child.”2

About her education, she wrote, “She [Emma’s mother] took a strong interest in the education of her children, who had their lessons at home. Owing to circumstances, my grandparents travelled frequently. They were always accompanied by a tutor and a governess. Quite often, the journeys lasted for several months and led through different countries. With all their travels, and with parents who regularly met and received interesting people, the children’s human and intellectual development was really exceptionally favoured. Apart from their schooling by different tutors and governesses, the children also attended courses and did a great deal of independent reading. All were marked by this education and benefited from it later on. Meeting any one of them, one was invariably struck by their culture and general knowledge.”3

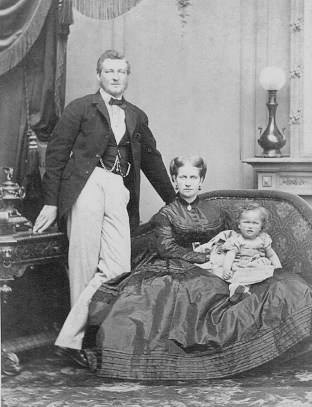

Emma and William – RP-F-F00650-E/Rijksmuseum

Emma and William – RP-F-F00650-E/RijksmuseumOn 7 January 1879, she married King William III of the Netherlands, who was 41 years older than she was. He had previously been married to Sophie of Württemberg, who had died in 1877. With Sophie, he had had three sons, of which one died young. At the time of his marriage to Emma, the younger William and Alexander were still alive. However, the younger William would die later that same year, deeply unhappy after being unable to marry the woman he loved. Both were vehemently against the marriage, and neither attended the wedding in Arolsen.

Emma gave birth to her only child, the future Queen Wilhelmina, on 31 August 1880. William had been present at the birth, encouraging Emma throughout the labour. William went to report his daughter’s birth in person, giving her the names Wilhelmina Helena Paulina Maria, for several of her ancestors and three of Emma’s sisters. Emma did not nurse Wilhelmina herself, as was tradition. Wilhelmina was just three years old when her only surviving sibling, Alexander, also died. She was now the heiress presumptive to the throne.

Emma and Wilhelmina – RP-F-F00650-E/Rijksmuseum

Emma and Wilhelmina – RP-F-F00650-E/RijksmuseumEmma received praise from Queen Victoria during the wedding of her sister Helena to Queen Victoria’s son Prince Leopold. Queen Victoria wrote to her eldest daughter, “The King of the Netherlands is as quiet and unobtrusive as possible; a totally altered man and totally owing to her. She is charming, so amiable, kind, friendly and cheerful. She would be very pretty were it not for her complexion which has suffered very much from the damp climate and is very red.”4 They visited the United Kingdom again the following year and they even brought along young Wilhelmina. As William’s health deteriorated over the next years, Emma and Wilhelmina followed him around Europe to several spas. During these years, Emma taught her daughter to embroider. Wilhelmina also learned to ride horses from an early age.

(public domain)

(public domain)In 1884, a law was approved that would make Emma regent if William died before Wilhelmina reached the age of 18 – which seemed very likely. When it became clear that Wilhelmina’s father would likely not live to see her 18th birthday, her education was sped up. Her education focussed on three languages, French, German and English but also included subjects just for her, like constitutional law and the organisation of the army. Emma was very involved in her daughter’s education. William died on 23 November 1890 and Wilhelmina officially became Queen of the Netherlands with her mother as regent.

Emma was inexperienced, but she learned quickly, and she also began sharing her experiences with Wilhelmina early on. During her regency, support for the monarchy grew. Emma realised all too well that the monarchy needed the support of the people, and she actively sought contact with them. Emma chose to continue to follow precedent where she could and was always well-informed on matters. While William found it difficult to work with ministers, Emma was more compliant.

Part two coming soon.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The life of Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 31, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Queen Emma’s regency law

After the death of Alexander, Prince of Orange, it became clear that it would be Wilhelmina who would succeed her father, and she would probably be a minor too. A regent would be required, and the Dutch Constitution demanded that a situation like that should be dealt with in a new law.

The last time this had been done was in 1850 when King William III’s sons were still minors. Back then, his brother Prince Henry was designated as regent, but he had now died as well. A conclusion was soon reached, Emma should be appointed regent – she really was the only viable option. However, even King William had his doubts, though he eventually agreed. The law designating Emma as regent was approved with a large majority of 97 to 3 on 1 August 1884. Emma would rule as Queen Regent from the death of her husband until Wilhelmina’s 18th birthday (at the time all other Dutch people did not reach their majority until their 23rd year).

The three people who voted against the law would have preferred to see a man act as regent, though they failed to say who that man should be. And Emma was not only a woman, but she was also a foreigner and quite young. They were not convinced that Emma knew the Netherlands enough to be able to rule it.1

On 20 November 1890, as William lay dying, Emma was called for the regency in her husband’s name. It was clear that he would not recover this time. He died in the early hours of 23 November with only Emma and Count Dumonceau by his bedside. The ten-year-old Wilhelmina officially succeeded him as Queen of the Netherlands but on 8 December 1890, Emma swore an oath in front of the States-General as regent and as her custodian.

The text of the oath as per the current law of 1994 goes as follows,

“I swear allegiance to the King2; I swear that I will maintain and uphold the Statute of the Kingdom and the Constitution in the exercise of the royal authority, as long as the King has not reached the age of 18 years. I swear that I will defend and save the independence and the territory of the Kingdom with all my might; that I will protect the freedom and the rights of all Dutch people and residents; that I will use all means available to me by law to maintain and improve the welfare, as a good and loyal regent must do. So help me, God almighty!”3

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Queen Emma’s regency law appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 30, 2020

Leopoldina of Brazil – The good sister

Leopoldina of Brazil was born on 13 July 1847 at the Imperial Palace of São Cristóvão in Rio de Janeiro as the third child and second daughter of Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, the younger brother of Queen Maria II of Portugal, and Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies. Her elder brother Afonso had died just one month before her birth, and the disappointment in her gender was twice as great.

On 11 July 1847, her father wrote to his stepmother, “With the most piercing grief I tell you that my dear little Afonso, your godson, unfortunately, died of convulsions that greatly frightened me.”1 Teresa Cristina’s grief was so intense that it was feared that she would miscarry, but she was safely delivered of a baby girl on 13 July. A year later, Teresa Cristina gave birth to her fourth and last child – a son named Pedro Afonso – who would live for just a year and a half. Leopoldina’s elder sister Isabel was confirmed as heir to the throne in 1852.

Leopoldina (left) with her parents and sister (public domain)

Leopoldina (left) with her parents and sister (public domain)They often spent the winter and spring at São Cristóvão and the summer and autumn at Petrópolis. The Empress and Emperor were affectionate parents, but the sisters’ upbringing was rather sheltered, and they lived their lives outside of the public eye. The sisters learned to read and write with the help of a teacher named Valdetaro, who called them “Little Ladies.” At the age of seven, Isabel was placed in the care of an aio (supervisor) who traditionally oversaw the education of the heir. He realised that Isabel and Leopoldina would need more than the traditional education for girls and wrote, “As to their education I will only say that the character of both the princesses ought to be shaped as suits Ladies who, it may be, will have to direct the constitutional government of an Empire such as that of Brazil. The education should not differ from that given to men, combined with that suited to the other sex, but in a manner that does not detract from the first.2 Tradition also required that the girls be educated by a woman and Pedro did not believe that there was a suitable woman for this task in Brazil. He turned to his stepmother Empress Amélie (born of Leuchtenberg), but she refused to take up the post. He eventually found a suitable woman with the help of sister Francisca; her name was Luísa Margarida Portugal de Barros, the Countess of Barral.

The Countess of Barral took up her post in 1856 and attracted the immediate dislike of the girls’ mother, who was the exact opposite of the enigmatic Countess. Yet, she hid her dislike as best she could, not wanting to antagonise her husband. The Countess was also well-liked by the two Princesses. By the end of 1850s, both girls were following a strict educational program that lasted 9,5 hours a day, six days a week. The Countess of Barral did not personally teach them all their subjects, but she did supervise. Even their father took it upon himself to teach his daughters. The Countess wrote of Leopoldina in 1859 that she was, “getting plumper, with a pretty complexion, and since she can’t read this letter, I can say, without making her conceited, that she is becoming very pretty.”3

Despite their excellent education, they were still kept in social seclusion and surprisingly, Pedro also excluded Isabel from the affairs of state. Yet, in 1863 – shortly before Isabel’s 18th birthday – Pedro launched the search for a husband for Isabel and Leopoldina.

Two Princes were chosen and shipped to Brazil so that the Princesses could meet them. Although Pedro would have the final say in the matter, he did not wish to force them. The Princesses did not learn of all of this until just three weeks before Prince Gaston, Count of Eu and his cousin Prince Ludwig August of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha were due to arrive. They first met on 2 September 1864 before returning the following day for a longer meeting. Prince Gaston wrote home, “The princesses are ugly, but the second decidedly less attractive than the other, smaller, more stocky, and in sum less sympathetic.”4 Though Isabel was love-struck, Gaston was less so. He wrote that the Emperor’s proposal, “at first greatly upset me, but I believe less and less that it is my duty to reject this important position that God has placed in my path.”5 Ludwig August had been instructed by his parents to only settle for Isabel, but he found that he preferred Leopoldina. The engagement between Isabel and Gaston was settled on 18 September 1864, and they were to marry just one month later.

On 15 December 1864, Leopoldina married Ludwig August, and they moved into a mansion near the palace called the “Palace Leopoldina”. Leopoldina fell pregnant soon after the wedding day, but she suffered a miscarriage in May 1865. She conceived again in July and gave birth to a healthy son named Pedro Augusto on 19 March 1866. While Isabel would have quite a bit of trouble conceiving, Leopoldina gave birth to three more sons in quick succession: Augusto was born on 6 December 1867, Joseph Ferdinand was born on 21 May 1869, and Ludwig Gaston was born on 15 September 1870.

Leopoldina with her husband and her eldest son (public domain)

Leopoldina with her husband and her eldest son (public domain)Leopoldina and Ludwig August began to divide their time between Brazil and Europe. Their three eldest sons were born in Brazil while the youngest was born in Austria. At the end of January 1871, Isabel was on her way to see her sister in Vienna when she received the news that Leopoldina had contracted typhoid fever. Isabel was only allowed to see her sister after all hope of recovery was lost. Leopoldina died on 7 February 1871 – just 23 years old. Isabel accompanied her sister’s body to Coburg for burial. She wrote, “My good Leopoldina whom I loved so much and who loved me so much, my only sister, the trusty companion of all my childhood and my youth! Faith is indeed the only consolation for such a loss! Leopoldina was so good that she is in heaven.”6

Leopoldina’s mother-in-law wrote, “May God’s will be done, my good Chica, but the blow is hard, and we are very unhappy. The state of my poor Gusty breaks my heart, he sobs at every moment, does not eat nor sleep, and it is a terrible change! She loved him so much. And they were so perfectly happy together! To see such happiness destroyed at age 24 is horrible!! And these poor children! I wrote you Saturday, and Sunday and Monday were calm and quiet. She did not open her eyes, but she heard what was being shouted in her ear, and she certainly recognised her sister’s voice, for she spoke a few words in Portuguese. Monday night the doctors found a sensible improvement, and we regained hope. The night was calm, but by Tuesday morning the chest was taken, and at 10 o’clock the doctors declared that there was no hope, and yet I still cared for her on this long day spent by her bed, seeing her so calm and so little changed; but by 4 p.m. the breathing became shorter. The abbot Blumel recited the prayer of the dying, we were all kneeling around her bed, and at 6 p.m., her breathing ceased, without the slightest contraction of her physiognomy. She was really beautiful then, and she had an angelic expression. Now she is lying in a coffin dressed in white silk clothes, a white crown, and her wedding veil over her head. She has not changed, it is good to look at her. She is all surrounded by fresh flowers, of crowns sent by all the princesses. Tomorrow there will be a religious ceremony at home, and she will leave for Coburg, where we will all attend, including Gaston and Isabel who are very good. The latter is desperate. I embrace you, pray for us, we much need it. All yours, Clémentine”7

One of Leopoldina’s granddaughters was Maria Karoline who was gassed by the Nazis in 1941.

The post Leopoldina of Brazil – The good sister appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 29, 2020

Irene of Hesse and by Rhine – The tragedy of the blood (Part two)

Irene fell pregnant quickly and gave birth to her first son Prince Waldemar on 20 March 1889. He was born in Kiel where Irene and Henry were at the time with her mother-in-law, who was now known as the Empress Frederick. After the birth, Queen Victoria wrote, “Thank God that all is so well over and darling Irene is well and had a quick, easy time and got as the Highlanders say, ‘a young son.’ Would you not all of you rather have had a girl? And how strange that he should be born on poor Fritz Carl’s birthday.1 However, we must all be thankful that the dear child is doing well.”2 Empress Frederick was shocked to find that neither Henry nor Irene read newspapers and she wrote that being with them in Kiel was like being ‘in Russia’ as the Romanovs also lived in total seclusion.3

Despite this, Empress Frederick became quite fond of Irene, not in the least because she managed to improve the relationship between the Empress and Henry. From the Köningliches Schloss in Kiel, Henry continued to perform naval duties, and he could indulge in his passion for cars. It soon became apparent that young Waldemar was a haemophiliac and it would take another seven years before Irene gave birth to a second son, named Prince Sigismund. A third son, named Prince Henry, was born in 1900. He too was a haemophiliac. Irene had been hoping for a girl while her sister Alix, now Empress of Russia, was fervently praying for a son.

Empress Frederick was by then seriously ill with cancer. Irene was among those who hurried to be by her side at Friedrichshof. She died, after a long and excruciating deathbed, on 5 August 1901. In 1904, in an eerily similar situation of the death of her brother Friedrich, Irene’s three-year-old son Henry fell from a chair and hit his head. He died of a brain haemorrhage shortly afterwards. Just a few months later, Irene’s sister Alix gave birth to the long-awaited Tsarevich Alexei – he too would be a haemophiliac. The truth was kept carefully hidden, but Alix confided in her sister Irene, who knew the anxieties better than anyone else. Although Irene’s eldest son was also a haemophiliac, he would live to the age of 56.

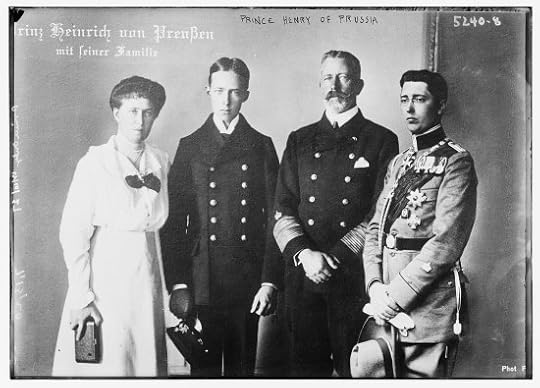

Irene and her family (public domain)

Irene and her family (public domain)The outbreak of the First World War set the family relations on edge. Irene travelled back to Kiel, where her husband was in command of the German Baltic Fleet. She even let her English maid go and hired a German one. Her elder sister Victoria returned to England and Alix tried to assure everyone that the war was the fault of the Prussians and not the Hessians. Elisabeth, who had married Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia but was by then widowed, remained in Russia. Both Elisabeth and Alix would be murdered. Irene, Victoria and Ernest Louis remained hopeful that the rumours were not true, but intelligence later reported that the entire family had been murdered.

Embed from Getty Images

At the end of the war, Irene and Henry were in fear of their lives. Revolutionaries swept through Kiel, and they tied red flags to their car to make their way out of the city. During the flight, Irene was shot in the arm.4 They eventually reached Hemmelmark in Germany, where they lived in obscurity. During the 1920s, Irene visited Anna Anderson, who claimed to be one of her nieces, Grand Duchess Anastasia. She later wrote, “I saw immediately that she could not be one of my nieces. Even though I had not seen them for nine years, the fundamental facial characteristics could not have altered to that degree, in particular the position of the eyes, the ears, etc… At first sight, one could perhaps detect a resemblance to Grand Duchess Tatiana.”5 She added, “We had lived earlier in such intimacy that it would have sufficed had she given me the least sign, or had made an unconscious movement to awaken in me a feeling of kinship and to convince me. I could not have made a mistake.”6 She had been so upset by the entire affair that her husband forbade Anastasia as a topic of discussion.7

Irene would outlive all her sisters, her husband and two of her sons. She died on 11 November 1953 at Hemmelmark. The New York Times reported, “She was a chairman of honour of the Schleswig-Holstein branch of the German Red Cross for many years and in spite of her age worked for several welfare organisations until her illness forced her to retire. She founded the Heinrich Children Hospital in Kiel. A granddaughter, Barbara, nursed Princess Irene during her illness and she was with her when she died. The funeral will be held on Saturday at Hemmelmark Castle. She will be buried at the side of her husband.8

She had two grandchildren by her second son, of whom the eldest still has descendants.

The post Irene of Hesse and by Rhine – The tragedy of the blood (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 28, 2020

Irene of Hesse and by Rhine – The tragedy of the blood (Part one)

Princess Irene of Hesse and by Rhine was born on 11 July 1866 as the daughter of Princess Alice of the United Kingdom and the future Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse. She was their third daughter, following Victoria and Elisabeth. Brothers Ernest Louis and Friedrich would follow, as would two more sisters; Alix and Marie. Irene was named for the goddess of peace as she was born during the Austro-Prussian War.

Alice, a daughter of Queen Victoria, would raise her daughters as was expected of 19th-century Princesses. They would learn to ride, paint and play music. They also followed a strict education with lessons throughout the day. They learned to speak English, French and German. They cleaned their own rooms and made their own beds and regularly accompanied their mother as she visited charitable institutions. An English nanny named Mary Anne Orchard took care of the Irene and her two younger sisters.

Embed from Getty Images

The happy family life experienced its first tragedy in January 1873 when three-year-old Friedrich did not stop bleeding for several days after cutting his ear. It soon became apparent that he suffered from haemophilia, the same disease that Irene’s uncle Leopold had. Just a few months later, Friedrich climbed onto a chair to wave from a window, but he slipped as he leaned forward and he fell through the open window. He appeared uninjured, but he died that night of a brain haemorrhage. Alice was devastated and wrote to her mother, “To my grave, I shall carry this sorrow with me.”1

A second tragedy followed in 1878 when Irene’s elder sister was the first to fall ill with diphtheria. Each of the children fell ill, except for Elisabeth, and she was sent to her paternal grandmother for her safety. Throughout this time, Alice nursed her children, but despite her loving care, four-year-old Marie died on 16 November. Irene’s father also became ill, but he recovered, as did her elder sister Victoria. The younger children, including Irene, remained dangerously ill and Ernest Louis continued to ask about little Marie, but Alice could not bring herself to tell him she had died. Eventually, she broke down and told him and gave him a kiss to console him – within days, Alice was dead of diphtheria. Slowly, the other children began to recover, but the disease had left a gaping hole in the family.

Queen Victoria felt for her Hessian grandchildren and invited them to Osborne for an extended holiday. They returned home to face a life without Alice but were regularly invited back to England. By 1880, Queen Victoria was pleased to learn that Prince Henry of Prussia – the son of Victoria, Princess Royal – showed an interest in his cousin Irene but Queen Victoria warned her granddaughters not to rush into marriage. On 23 July 1885, Irene acted as a bridesmaid in the wedding of her aunt Beatrice to Prince Henry of Battenberg and Prince Henry of Prussia also attended, and he quietly courted Irene. On 5 October 1886, Henry’s mother wrote to her mother Queen Victora, “He is very much attached to Irene. The Empress says she knows he is not. He wrote so nicely about her – and said if he was only worthy of her.”2

The engagement between Irene and Henry was announced during Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee year on 22 March. His father – who was already seriously ill with throat cancer – could barely be heard as he made the announcement. Henry’s grandfather, William I, German Emperor, died on 9 March 1888 but his father, now Frederick III, was already terminally ill. He had undergone a tracheotomy in February to allow him to breathe more easily.

Henry and Irene were married on 24 May 1888 at the chapel of the Charlottenburg Palace. Henry’s father was present, but he struggled through the ceremony and was exhausted afterwards. The New York Times later reported, “Before the ceremony the royal family assembled in the Blue Drawing Room, where the Empress affixed the Princess’s crown upon the bride’s head, using a gold toilet service presented by Czar Alexander I to Queen Louisa.[…] Prince Henry’s ‘yes’ resounded through the chapel. Princess Irene’s response was given timidly and in a low tone. At the close of the ceremony, the bridal couple approached the Emperor who, deeply moved, held his son in his arms and repeatedly kissed him on the cheek and brow. His Majesty congratulated Princess Irene in the heartiest manner.[…] The bride, Princess Irene of Hesse, wore a low-necked dress, trimmed with large diamonds and a large necklace set with diamonds. Her breast ornaments, which were diamonds, and her bracelets were all ancient royal jewels.”3 Later that day, Irene and Henry travelled by a special train to Erdmannsdorf, where they would spend their honeymoon. Irene’s father-in-law died just one month later.

Part two coming soon.

The post Irene of Hesse and by Rhine – The tragedy of the blood (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 27, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The first broadcast of Radio Orange

On 13 May 1940, Queen Wilhelmina escaped from the invading German troops and travelled on the HMS Hereward to England. Later that day, Queen Wilhelmina arrived at Harwich, where the British authorities had already arranged for a train to London. Wilhelmina wrote, “At the station, I was met by King George and by my children, who were very upset and did not understand that I should have had to follow them so soon. The King asked me to be the guest of himself and the Queen, and escorted me to Buckingham Palace.”1

The following day, she issued another proclamation telling the people that the government had to be moved abroad. “Do not despair. Do everything that is possible for you to do in the country’s best interest. We shall do our best. Long live the Fatherland!”2

On 24 May, Wilhelmina spoke on the radio for the first time during the war. From 28 July, the BBC broadcasted Radio Oranje (Orange) where Wilhelmina spoke 48 times over the course of the war to encourage the Dutch people. Radio Orange was broadcast for 15 minutes and began with the words, “Radio Orange Here, the voice of a combatant Netherlands.”3

During her first broadcast, she spoke the following words;

“I am delighted that thanks to the benevolent cooperation of the English authorities, this Dutch quarter-hour has been incorporated into the broadcasts of British radio, and I express the hope that many fellow countrymen, wherever they may be, will now be faithful listeners of the patriotic thoughts that reach them along this way. And now I am delighted to be the first to speak to you in these fifteen minutes.

“First of all, I would like to commemorate with you all the Fatherland, so deeply affected by the calamity of war. We commemorate the untold suffering that has come upon our people and that it is now constantly experiencing. We want to pay tribute to the heroes, who fell victim to their duty in the defence of our Netherlands, tribute to the courage of our resistance, which on land, at sea and in the air, with the effort of her utmost strength, have been able to withstand a much stronger assailant much longer than he expected.

“After all that has already been said and written about the war in which we are wrapped up, you will certainly not expect that I will deal briefly with the war itself and the many issues related to it. But we must realise that the war increasingly reveals its true character, as being in its deepest essence a battle between good and evil, a battle between God and our conscience on the one hand and the dark powers that reign supreme in this world. It is a struggle – which I need to tell you – belongs in the spiritual world and is fought deeply hidden in the heart of man, but which has now emerged in the most appalling way in the form of this great worldly struggle, of which we are the unfortunate victims and which causes suffering to all nations. This war is all about giving the world a guarantee that those who want good will not be prevented from accomplishing it. Those who believe that the spiritual values acquired by mankind can be destroyed by the edge of the sword must learn to realise its vanity. Crude violence cannot deprive people of their convictions.

“As in the past neither gun violence, nor the flames of the pyre, nor the impoverishment and suffering of our sense of freedom, our freedom of conscience and our freedom of faith have ever been able to wipe us out, so I am convinced that even in the present age we and all who think as we do – whatever people they may belong to – are strengthened from this trial and through all that is sacred to them and we will rise.

“That it is for this lofty purpose that thousands of our brave have already made the sacrifice of their lives and that this sacrifice has not been in vain, for the comfort of their relatives and for all of us. Although the enemy has also occupied the national soil, the Netherlands will continue the battle as long as a free happy future appears before us. Our beloved tricolour flies proudly on the seas, in the larger Netherlands in East and West; and side by side with our allies, our men continue the battle. The parts of the Overseas Empire, which so aptly expressed their compassion for the disaster that struck the Motherland, are more closely than ever associated with us in their thinking and feeling. In unbreakable unity, we want to maintain our freedom, our independence and the territory of the entire Empire. I implore my countrymen in the Fatherland and wherever they are to continue to trust, no matter how dark and difficult the times are, in the final victory of our cause, which is strong not only by the strength of arms but no less by the realisation that it concerns our most sacred goods. I have said.”4

For the first few years, her speeches were recorded on a gramophone record which was then played by the BBC. From March 1942, she began to speak live from the studio. She wrote her own speeches and often worked for hours on them.

It was illegal for the Dutch people to listen to English radio and the Nazis eventually demanded everyone to turn in their radio. Many kept their radios to be able to listen to the broadcasts as they also often included coded messages for the resistance. After the war, Wilhelmina was criticised for not putting enough emphasis on the plight of the Jewish people.

Wilhelmina later wrote of her broadcasts, “My broadcast speeches were not only concerned with the new times. They also aimed at inspiring and stiffening resistance against the oppressor and at informing the nation of the government’s policy. At the same time, I did what I could to assist my countrymen in their spiritual struggle and paid homage to those who have given their lives in the great cause.”5

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The first broadcast of Radio Orange appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The meeting between William and Emma

The Baroque Schloss Pyrmont was the scene of one of the most famous lines in Dutch royal history.

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksKing William III of the Netherlands arrived here on 28 July 1878 to court Pauline of Waldeck and Pyrmont. Pauline rejected the elderly King but her sister Emma supposed exclaimed, “We cannot just let the poor man go home alone!”1 Emma and William were 41 years apart in age and he was almost 14 years older than her own father. Nevertheless, she must have seen something in him that others did not see. Even Queen Victoria wrote of him that he was “not an enviable relation to have.”2 Just three years later, she wrote of Emma and William, “The King of the Netherlands is as quiet and unobtrusive as possible; a totally altered man and all owing to her. She is charming, so amiable, kind, friendly and cheerful.”3

One of the men accompanying the King later wrote of the four days they spent in Pyrmont, “One of the days we spent in Pyrmont, I had the honour of accompanying the Princesses (Emma and Pauline) and the King on a wonderful carriage ride, and we also went up on a marvellously high watchtower. One can say that the love had not given the King wings but it certainly gave him legs for he was normally slow and made himself comfortable and he now climbed the dozens of steps leading to the top of the tower.”4

In any case, after the second visit in September, the engagement between Emma and William was announced and they were married early the following year. The birth of their daughter Wilhelmina completed the new family.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The meeting between William and Emma appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 26, 2020

Marie Antoinette and The “Let them eat cake” myth

Marie Antoinette has gone down in history as one of the most despised Queens, not in the least because of her perceived indifference to the plight of the poor and for saying something she never did… “Let them eat cake.”

Born an Austrian Archduchess on 2 November 1755 as the daughter of Empress Maria Theresa and Francis of Lorraine, Holy Roman Emperor, Marie Antoinette married the Dauphin of France, later King Louis XVI, in 1770. He became King just four years later with Marie Antoinette as his Queen.

The Let them eat cake incident was first told about Maria Theresa of Spain, the Queen of Louis XIV of France, a century before Marie Antoinette even arrived in France in the form of Let them eat crust (croute) of the pate. It continued to be repeated about a series of Princesses, like Madame Sophie and Madame Victoire, throughout the 18th century before being wrongly ascribed to Marie Antoinette. If anything, Marie Antoinette would have been the one to give her own cake to the starving people.1 In the memoirs of the Count of Provence, published in 1823, he commented that eating pate en croute always reminded him of a saying of his ancestress, Maria Theresa of Spain.2

Marie Antoinette was known for her charity, even though her good works were later buried under accusations of indulgence. When breaking the news of her first pregnancy to the people of France, Marie Antoinette asked her husband for 12,000 francs to send to the relief of those in the debtors’ jail in Paris – particularly for those in jail for failing to pay their children’s wet-nurses and the poor of Versailles. She wrote, “Thus I gave to charity and at the same time notified the people of my condition.”3 As a young Queen, Marie Antoinette cared for a peasant injured in the royal stag-hunt, and it was for acts like these that she wanted to be remembered – she wanted the love of the people and was easily touched by the less fortunate. She had compassion and even instructed her young son on the need to care for unfortunate children.4

During the time of the Flour War in 1775, Marie Antoinette’s reputation was damaged due to a series of riots with many blaming her for the economic situation and the high prices of flour and bread. The Let them eat cake rumours attributed to Marie Antoinette came from around this time. Instead of uttering the ignorant words, Marie Antoinette was writing to her mother on the duties of royalty. “It is quite certain that in seeing the people who treat us so well despite their own misfortune, we are more obliged than ever to work hard for their happiness. The King seems to understand this truth; as for myself, I know that in my whole life (even if I live for a hundred years) I shall never forget the day of the coronation.”5

As her unpopularity deepened, Marie Antoinette took desperate measures to win back the love of the people. She mingled with the crowds and opened up the Trianon for the public on Sundays. People were disappointed not to see rooms paved with diamonds and believed them to be off-limits rather than non-existent. Her extravagance is not in doubt, nor is the rest of the French Royal Family’s. They lived in a world of unimaginable luxury, and the extravagance only fueled the fire of the revolution. Marie Antoinette’s sister Maria Caroline wrote, “My poor sister. Her only fault was that she loved entertainments and parties, and this led to her misery.”6 There was more to it than that, of course, especially if you factor in the utter humiliation she lived for the first eight years of her marriage. But to accuse Marie Antoinette of ignorance of the situation in France, it simply doesn’t add up.

The post Marie Antoinette and The “Let them eat cake” myth appeared first on History of Royal Women.

July 25, 2020

Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy by Matthew Lewis Book Review

When King Henry I of England died, he had just one living legitimate child – a daughter named Matilda. Although many had sworn an oath to accept her as his successor, it was instead her cousin Stephen who became King of England, leading to many warring years known as the Anarchy. It was a complex and difficult situation.

Matilda succeeded briefly in taking Stephen hostage but she never quite managed to claim the throne and become a Queen in her own right. This right would be reserved for a woman four centuries later. It was Matilda’s son who succeeded Stephen as King.

Matthew Lewis manages to write a balanced and well-researched book about a confusing time in England. As Matilda battles for her rights and eventually her son’s rights, we also see Stephen’s side of the story. I also enjoyed the alternating chapters and the many images included.

Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy by Matthew Lewis is one book you should not miss. It is out now in both the US and the UK.

The post Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy by Matthew Lewis Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.