Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 168

September 7, 2020

Alexandra of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha – Queen Victoria’s granddaughter (Part one)

Alexandra of Edinburgh was born on 1 September 1878 at Schloss Rosenau as the fourth child and third daughter of Alfred, the future Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (then known as The Duke of Edinburgh) and Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia. Her siblings were Alfred (born 15 October 1874), Marie (born 29 October 1875), Victoria Melita (born 25 November 1876) and Beatrice (born 20 April 1884). Her mother also had a stillborn son.

Alexandra and her sisters had a Scottish nurse named Nana Pitcathly. She spent her early childhood in England before moving to Malta in 1886 when her father was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean squadron. They moved to Coburg in 1889 as her father was the heir apparent to the duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Her great-uncle died on 22 August 1893, and her father succeeded as the reigning Duke. Alexandra remained a British Princess, as a male-line descendant of Queen Victoria, but she now became known as Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Embed from Getty Images

In April 1894, her father organised a shooting party at Obersdorf where Alexandra met Prince Ernst of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the future Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. He was a grandson of Queen Victoria’s half-sister Feodora. He fell head over heels with her, and her mother wrote to her eldest sister Marie (who had married the future King Ferdinand I of Romania in 1893), “But what I feared has happened: would be you believe that Ernie Hohenlohe had fallen madly in love… with… Sandrinchen! What do you think of it! I, who only dreaded a flirtation more on her part, was soon obliged to see very plainly, that he was getting more and more devoted to her, he would hardly ever leave her, and when she was not near him, his eyes were following him everywhere. He was so miserable to leave, that I thought every moment he would ask to talk to me. But it seems, he was far too bien élevé1 to put in a word himself and never made any allusion of his attachment to Sandra. She knows nothing about it, and I want her to ignore it for some time to come. She was always very gay with him and seemed to like him, but not exactly flirty. I think he was so devoted to her that she needed no flirting to keep him always at her side. He opened his heart to his father, who discouraged him greatly and told him to keep away as much as possible and I saw how hard he tried to do it, but he simply could not!”2

She continued saying that she had received a letter from Ernst, “telling me about his great love for Sandra and imploring me, to allow him to see her again after some time, as he could not bear to think, that she might forget him!”3 Her mother simply thought she was too young, and Ernst was also 15 years older than her.

Alexandra went to visit the pregnant Marie after this and Marie had a long talk with her about Ernst. Alexandra stated that she was very fond of Ernst while Marie told her to wait before making up her mind. Marie wrote to their mother, “I will tell you quite honestly as much as I know Sandra I do not think that it would be good for her, especially as we two have married very well.”4 Early the following year, as Alexandra returned to her mother, Ernst came to visit with them. When he left again, he wrote several anxious letters to Alexandra’s mother – he really had it bad.

Alexandra and Ernst were engaged in the spring of 1895, despite the fact that her mother had wanted to postpone any thought of an engagement until her 17th birthday. The wedding was set for 20 April 1896 at Coburg. Many family members gathered to attend the celebrations, such as the future King George V and Queen Mary, who represented Queen Victoria, and Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany and his wife, Auguste Viktoria. Alexandra’s sister Marie and her husband were also there. Mary wrote to her mother describing their arrival, “Sandra is delighted with your & Papa’s present which is very pretty & will be most useful to them, they have very few presents, such a contrast to our mass.5 The newlyweds moved to Langenburg.

The post Alexandra of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha – Queen Victoria’s granddaughter (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 6, 2020

Queen Elizabeth I – A Tudor Princess (Part one)

On 7 September 1533 at 3 in the afternoon, Anne Boleyn gave birth to a daughter at Greenwich who would be named Elizabeth. Elizabeth’s father, King Henry VIII of England, had broken with Rome in order to annul his first marriage to Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne. He and Catherine had just one surviving child together – the future Queen Mary I. Anne’s triumph would have been complete if Elizabeth had been a boy, but it was not to be. However, Anne had lived through the birth, and there was hope for the future. A celebratory Te Deum was sung in St Paul’s for the happy delivery of a princess.

Just three days after her birth, Elizabeth was christened with neither parent attending the ceremony, as was customary. Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was her godfather. For the first three months of her life, little Elizabeth stayed with her mother at Greenwich but by December 1533, Elizabeth was taken to her own household at Hatfield in Hertfordshire. Anne’s aunt Lady Anne Shelton and her husband Sir John were in charge of Elizabeth’s household, along with Margaret, Lady Bryan – a half-sister to Anne’s mother. Elizabeth’s half-sister, the now illegitimate Lady Mary, was also called to join the new Princess’ household. Lady Bryan regularly wrote to the court to inform her parents of her progress, and her parents also paid her visits whenever they could. In addition to Hatfield, Elizabeth was moved to other residences to allow for thorough cleaning of the residences.

Elizabeth was not yet three years old when her mother was executed on 19 May 1536. Her parents’ marriage was annulled, and so Elizabeth too was made illegitimate. In July 1536, Parliament repealed the Act which made Elizabeth her father’s heir. Though the sisters would never be particularly close, Mary did bring Elizabeth to the Christmas court of 1536, and they were also at court for the christening of their new little brother – the future King Edward VI – who was born to Henry and his third wife Jane Seymour in October 1537. Jane tragically died two weeks after the birth. Lady Bryan went on to serve in his household while Elizabeth received Lady Troy as governess and Katherine Champernowne (later Ashley) as a gentlewoman in waiting. Katherine Ashley would remain close to Elizabeth all her life, and she was responsible for her initial education. Both Mary and Elizabeth now settled at Hunsdon.

One of Elizabeth’s first tutors was William Grindal, and he built on the education already provided by Katherine Ashley. Elizabeth’s first surviving letter was written in 1544 in Italian and was addressed to Catherine Parr – Henry’s sixth and final wife. Before this, Elizabeth was occasionally at court – like for the arrival of Henry’s fourth wife Anne of Cleves. Elizabeth’s daily life was barely recorded during these years, but she was an excellent scholar. The Third Succession Act of 1543 confirmed Edward as Henry’s successor, and it also returned both Mary and Elizabeth to the line of succession, though both sisters remained illegitimate.

On 28 January 1547, King Henry VIII died, and he was succeeded by Elizabeth’s younger brother who now became King Edward VI at the age of 9. Her brother wrote to her, “There is very little need of my consoling you, most dear sister, because from your learning you know what you ought to do, and from your prudence and piety you perform what your learning causes you to know… I perceive you think of our father’s death with a calm mind.”1

Elizabeth was left £3000 a year with a further £10000 upon marriage. For now, nothing much changed for Elizabeth, and her main focus continued to be her education. Elizabeth was taken into the household of Catherine Parr, the widowed Queen, who soon remarried to Thomas Seymour, King Edward VI’s maternal uncle and the brother of the Lord Protector, Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset. She may have shared her lessons with Lady Jane Grey, who also briefly resided there. Elizabeth left the household in June or July 1548, following an unsettling situation with Thomas, and Catherine died following childbirth in September of that same year.

Elizabeth was apprehensive about sending him condolences following Catherine’s death, so whatever happened must have troubled her. He apparently wanted to marry her but he was arrested the following year, and Elizabeth was interrogated. He was executed on 20 March 1549 on several charges of treason. Elizabeth eventually settled at Hatfield with a household of some 140 people. Katherine Ashley, who had encouraged the talk of Thomas Seymour, had been arrested and also interrogated and, although she was released, she was removed from Elizabeth’s household. Katherine was restored to her former position in Elizabeth’s household in late 1549.

It would not be Elizabeth’s last brush with authority, and it would take a lot for this Tudor Princess to survive to become Queen.2

Part two coming soon.

The post Queen Elizabeth I – A Tudor Princess (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Grave of Queen Frederica and King Paul of Greece vandalised

A police patrol discovered the damage to the grave in the Royal Cemetery of Tatoi Palace. The large cross that stands over the grave had been broken into three parts. The Ministery of Culture announced that plans to repair the grave had been set in motion immediately but no arrests have been made.

(public domain)

(public domain)Tatoi Palace was once the summer residence of the Greek Royal Family and it is located 27km (17 mi) from the city centre of Athens. When the Greek monarchy was abolished, it became the private property of the family until 1994, when it was confiscated by the government. Former King Constantine II took the matter to the European Court of Human Court, which ruled in his favour in 2003 and he received €12m in compensation.

The post Grave of Queen Frederica and King Paul of Greece vandalised appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 5, 2020

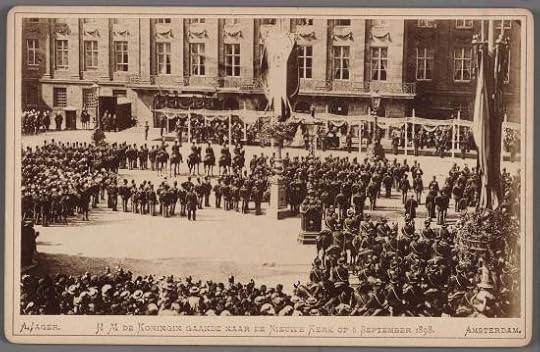

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The Inauguration of Wilhelmina

Just six days after her 18th birthday, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands walked from the Royal Palace in Amsterdam to the adjacent New Church to have her inauguration as Queen of the Netherlands. She had succeeded her father as a girl of 10, and for eight years, her mother had served as regent – now her personal reign would begin. She wore the same mantle her grandfather King William II had worn in 1840.

Queen Wilhelmina walks to the church (public domain)

Queen Wilhelmina walks to the church (public domain)Before swearing an oath to the Dutch Constitution, she held a short speech in which she said, “I believe it to be a great privilege that it is my task and duty in life to devote all my strength to the wellbeing and growth of the Fatherland so precious to me. I make the words of my beloved father my own, “Orange can never, yes never, do enough for the Netherlands.”1 Her mother sat slightly behind her on the podium.

CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

CC0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe oath goes as follows:

“I swear to the people of the Kingdom that I will maintain and uphold the Statute of the Kingdom and the Constitution. I swear that I will defend and maintain the independence and the lands of the Kingdom with all my might, that I will protect the freedoms and the rights of the Dutch citizens and inhabitants, and to use all means available to me by law for the maintenance and improvement of the welfare, like a good and loyal King is obligated to do. So help me, God Almighty!”2 Following her own oath, all of the present members of the States-General swore their allegiance to her.

(public domain)

(public domain)She later wrote in her memoirs of the moment she walked into the church all alone, “A feeling of emptiness and complete loneliness came over me.”3 Prime Minister Pierson was deeply touched by the inauguration and wrote, “The inauguration was so very impressive that it touched all of our souls.”4

Exactly 50 years later, Queen Wilhelmina’s only surviving child Juliana was inaugurated as Queen of the Netherlands.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The Inauguration of Wilhelmina appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 3, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The abdication

When I studied history, I was particularly struck by the abdication of Emperor Charles V in 1555. I recognized the wisdom in it.1

Queen Wilhelmina’s decision to abdicate certainly caused some raised eyebrows with her British cousins, who had been left reeling by the abdication of King Edward VIII in 1936. When the future Queen Elizabeth II dedicated her entire life to her people at the age of 21, Queen Wilhelmina commented, “She has definitely settled better to the inevitable than me and has raised herself higher above it.”2

Wilhelmina would not be the first Dutch monarch to abdicate – King William I abdicated in 1840 after wishing to marry Henriette d’Oultremont, his late wife’s lady-in-waiting. Not only that, the Dutch Constitution expressly took abdication into account. Wilhelmina had begun toying with the idea of abdication in 1938, after a personal reign of 40 years. She had brought up the topic at a family dinner, but her daughter had not been up to it yet. Though the Second World War temporarily put all plans of abdication on hold, she continued to mention it occasionally in her letters to her daughter. By 1947, she was physically worn out and suffering from a heart condition which made it necessary for Princess Juliana to act as regent twice. Though her daughter tried to convince her to hold off her abdication until her golden jubilee, Wilhelmina dreaded celebrating another jubilee.

In her memoirs, Wilhelmina wrote, “It was only after the period of transition following the liberation that I felt justified in seriously considering the question of abdication. An incentive was provided by my daily duties, which were more numerous than before the war and left my spirit little or no time for relaxation, which did not help my fitness at moments when special demands were made of me.”3

On 12 May 1948, Wilhelmina announced her intention to abdicate in a speech on the radio. The date had some significance as the date of her father’s inauguration 99 years earlier. On 31 August 1948, a grand celebration took place in the Olympic Stadium of Amsterdam where she spoke the words, “I have fought the good fight.”4

She would officially abdicate on 4 September 1948, 50 years and four days since the start of her personal reign. She signed her abdication in the Royal Palace of Amsterdam which was co-signed by her daughter and son-in-law. She later wrote, “When we entered we found a somewhat subdued atmosphere, which was however soon improved by my happy and cheerful manner. How numerous were and are my reasons for gratitude, in the first place, my confidence in Juliana’s warm feelings for the people we both love so much and in her devotion to the task that was awaiting her and her ability which she had proved on various occasions. Then also the fact that my office was transferred to her during my lifetime and that I might have the opportunity to see something of her reign. Really, there was no room for sadness in my heart.”5

Then Wilhelmina – who had now reverted back to the title and style of Her Royal Highness Princess Wilhelmina – took her daughter to the balcony of the palace to introduce her as the new Queen. She said, “I am honoured to inform you myself that I just signed my abdication in favour of my daughter Queen Juliana. I thank you all for the trust you have placed in me for the last fifty years. I thank you for the affection with which you have surrounded me every time. I look to the future with confidence with my darling only child in charge. God be with you and the Queen. And I am happy to say with all of you, long live our Queen! Huzzah!”

Princess Wilhelmina left the palace through the back door later that day.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The abdication appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 1, 2020

The Prinzenpalais in Oldenburg

The Prinzenpalais in Oldenburg began its life in 1826 as a residence for the orphaned grandchildren of Peter I, Grand Duke of Oldenburg, the sons of Duke George of Oldenburg (died 1812) and Catherine Pavlovna of Russia (died 1819) but they only lived in the palace for three years.

In 1852, the future Peter II, Grand Duke of Oldenburg took up residence in the Prinzenpalais, and he married Elisabeth of Saxe-Altenburg the following year and he became Grand Duke that same year. However, after Peter, the building was used in many different ways. It was a military hospital, a school and a land registry office. It was then extensively renovated and restored to its former glory. It opened as a part of the Landesmuseum in 2003.

Click to view slideshow.

Many original features still survive but many appear to be in bad shape. It certainly needs some new loving. You can visit it together with Schloss Oldenburg and the Augusteum with a day ticket. Also, there is very little attention to the palace’s former life, not even a little leaflet is to be found. Such a shame!

The post The Prinzenpalais in Oldenburg appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 31, 2020

Edward II’s Nieces: The Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown by Kathryn Warner Book Review

The Clare sisters were the daughters of King Edward II’s sister Joan of Acre and her first husband Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester. They were named Eleanor, Margaret and Elizabeth. With the death of their only brother Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Hertford, the three sisters became heiresses. Their proximity to the King brought them favour but could also be troubling.

With their lives literally in the hands of their uncle, the sisters were married off if it suited him and they rose and fell in favour throughout their lives. If anything, the book proves that medieval had little say in their own lives, no matter how rich you were. Edward II’s Nieces: The Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown is an interesting look at the lives of these medieval women. It is well-written, and you can tell it has been well-researched. The only trouble I had is that the women were often referred to by whatever married name they had at the time, making it a little confusing. Perhaps with so many marriages, it would have been easier to stick with their maiden name.

Nevertheless, I’d still highly recommended this book for those interesting in the complex court of King Edward II and Queen Isabella.

Edward II’s Nieces: The Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown by Kathryn Warner is available now in the UK and the US.

The post Edward II’s Nieces: The Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown by Kathryn Warner Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 30, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The birth of Wilhelmina

In early 1880 the new Queen Emma of the Netherlands realised she was expecting. By March, rumours were circulating around the country. In the evening of 30 August 1880, Emma went into labour at Noordeinde Palace and her husband was by her side throughout. A Princess was born the following day at six o’clock in the evening, much to (almost) everyone’s joy. A 51-gun salute welcomed the Princess. King William showed no disappointment in the gender of his fourth child. She received the names Wilhelmina (a traditional Orange-Nassau name) Helena Pauline Maria (after three of Emma’s sisters). The following day, William registered the birth himself and insisted on showing off the newborn Princess to the gentlemen in attendance, calling her “a beautiful child.”1

At the time of her birth, the future Queen was third in the line of succession. At the time, the Netherlands operated on a semi-salic line of succession, and so, she was behind her elder half-brother Alexander (the only one of her three half-brothers still living) but also behind her great-uncle Prince Frederick. Prince Frederick died in 1881 without any surviving sons, followed by the unmarried Alexander in 1884, leaving Wilhelmina as her father’s heir at the age of four.

Emma would not nurse the newborn Wilhelmina herself – she had two wetnurses, one at Noordeinde Palace and one the Loo Palace. And while her parents were overjoyed, several newspapers expressed their disappointment with headlines like, “It’s only a girl!”2 Only a son could have saved the royal house, with a girl the crown would inevitably pass to another house. Nevertheless, congratulations began pouring in soon after the birth. Emma’s sister Pauline wrote to William that little Wilhelmina would be the joy of the rest of his life.3

The first years of her life appear to have been happy. She was appointed a governess named Cornelia Martina, Baroness van Heemstra, in 1882. She also had a carer named Marie Louise de Kock and a nanny named Julie Liotard, who also taught her French and so Wilhelmina was raised bilingual. Wilhelmina would remain the only child of her parents though she did not mind this, and she later wrote about the joy of having her parents all to herself.4 When it became clear that she would become Queen sooner rather later, her education began in its earnest.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The birth of Wilhelmina appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Happy Princess’s day!

These days the Netherlands celebrates King’s Day but the traditional birthday celebrations for the monarch actually began (again) with Queen Wilhelmina, when she was just a Princess.

Princess Wilhelmina’s father King William III was not quite the popular monarch he perhaps hoped to be, but his adorable four-year-old daughter and future Queen was very popular. A certain newspaper offered the suggestion that perhaps the birthday celebrations the country had once done for its first King, should now be done for the Princess. It also helped that her birthday was in August, while her father’s birthday was in dreary February. They said it should be “a day where we put aside all grievances and feuds and to remember that we are countrymen and that a bond unites us all.”1

People liked the idea and so the first Princess’s day was celebrated on 31 August 1885 for Wilhelmina’s fifth birthday. Princess Wilhelmina was paraded through the city of Utrecht, and in the following years, other cities followed. When Princess Wilhelmina’s inherited the throne in 1890 at the age of 10, the day was renamed Queen’s Day.

The festivities continued to grow, but Queen Wilhelmina rarely attended after she became an adult. During the Second World War, celebrations of Queen’s Day were banned by the Germans. When Queen Wilhelmina abdicated in favour of her daughter Juliana, the Queen’s Day celebrations were moved to Juliana’s birthday on 30 April. The first celebration in April included a circus at the Amsterdam Olympic Stadium, but the family did not attend – preferring to stay at Soestdijk Palace where they received a floral tribute. When this tribute came to be televised in the 1950s, Queen’s Day increasingly became the national holiday we know today.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Happy Princess’s day! appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 29, 2020

Queen Jiangshi – The Kingmaker

Queen Jiangshi was one of the most virtuous women in ancient China. She has been lauded as a successful kingmaker and for taking decisive actions.[1] When her husband Chong’er, an exiled prince, was reluctant to reclaim his rightful throne, Queen Jiangshi took decisive action in his stead. She even attempted to kidnap him where he would be taken to Jin and proclaimed king. The kidnap attempt spurred her husband to action where he became one of Jin’s greatest rulers.[2] Thus, many poets and historians have praised her for her actions because if it were not for her, King Chong’er would never have known of his potential to rule and Jin would have lost out on a great ruler that made them a powerful state in China during the Spring and Autumn Period.[3]

Queen Jiangshi lived during the Spring and Autumn Period. This period lasted from 771 to 476 B.C.E.[4] During this era, the states of China were breaking away from the crippling Zhou dynasty and forming their own dynasties.[5] In this period, Qin, Qi, and Chu were the powerhouses of China.[6] Jin would be one of the top powers of China, but it needed the guiding hand of Queen Jiangshi to get there.[7] This is the story of how Queen Jiangshi helped make Jin into a power state.

Queen Jiangshi was the daughter of the king of Qi.[8] She was born around 658 B.C.E. in the Qi capital (somewhere northeast of the modern city of Zibo in Shandong Province).[9] She was known to be very clever and had been educated in the classics.[10] Her father married her to Chong’er, a prince from Jin who came to Qi to seek refuge. His step-mother, Princess Liji of Li Rong (see the article “Princess Liji – A Vicious Beauty” for more information on Prince Chong ’er’s background and situation) had framed Prince Chong’er and one of his brothers for planning a rebellion against his father, the Duke of Jin.[11] Convinced of his sons’ treason, the Duke of Jin ordered their deaths.[12] However, Prince Chong’er and his brother escaped from Jin. Prince Chong’er eventually arrived in Qi, where he lived in exile for nineteen years.[13]

Prince Chong’er had no ambition for power. He wanted to have a peaceful, easy life in Qi.[14] However, his wife, Princess Jiangshi, was not content with her husband’s current position. She was ambitious and wanted her husband to take his rightful place as the ruler of Jin. Her opportunity came when a maidservant told her that Prince Chong ’er’s followers were planning to leave Qi and take him back to Jin.[15] Princess Jiangshi could not afford to pass up her husband’s chance of becoming king and began to urge Prince Chong’er into taking action.

Princess Jiangshi tried to persuade her husband to leave Qi as soon as he could so he could take the Jin throne.[16] She told him it was the right time to make his move because Jin was in a state of political turmoil ever since the death of his father.[17] However, Prince Chong’er was in his sixties, and the last thing he wanted was to rule an unstable kingdom.[18] He was content with spending the rest of his days in Qi because his life was stable and tranquil.[19]

Princess Jiangshi was frustrated with her husband’s reluctance.[20] She planned to get him drunk and kidnap him.[21] He would then be taken to Jin and be made king.[22] Princess Jiangshi conspired with Prince Chong ‘er’s friend, Jiufan. They got him drunk.[23] Then, Jiufan put him in a wagon and began to head for Jin.[24] When Prince Chong’er regained consciousness, he became angry and chased away Jiufan.[25] However, Prince Chong’er realized that his reluctance was futile.[26] He decided to continue to Jin to reclaim his rightful inheritance.[27] With the help of Duke Mu of Qin, who provided him with military assistance, Prince Chong’er took the throne of Jin and became king.[28]

King Chong’er sent for Jiangshi to come to Jin.[29] However, she was not proclaimed his principal wife. King Chong’er instead made her his fifth queen out of all his nine queens.[30] However, Queen Jiangshi did not resent her status. Chinese literature has praised her modesty in accepting her position as the fifth queen in King Chong ’er’s harem.[31] Throughout his reign, King Chong’er made alliances with other regional kings in Jin and promised them his protection.[32] In the end, King Chong’er made Jin one of the top powers during the Spring and Autumn Period.[33]

Queen Jiangshi is praised throughout Chinese literature. She is included in the “Biographies of the Virtuous and Wise” section in Biographies of Eminent Women, where she is portrayed as “just and honest” [34] and “having urged her husband to action” [35]. Other poems have also praised her:

“Selfish Qi Jian was not,

Justice she always upheld,

And the king became king of kings

As the queen had laid the foundation.”[36]

Sources:

Eno, R. (2010). 1.7. Spring and Autumn China (771-453). Indiana University, PDF.

L. Yunhuan. (2015). Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century (B. B. Peterson, Ed.; F. Hong, Trans.). London: Routledge.

Cook, C. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge.

[1] Yunhuan, p. 22

[2] Cook, p. 34

[3] Yunhuan, p. 22

[4] Eno, p. 2

[5] Eno, pp. 6-7

[6] Eno, p. 3

[7] Cook, p. 34

[8] Yunhuan, p. 21

[9] Yunhuan, p. 21

[10]Yunhuan, p. 21

[11] Cook, p. 41

[12] Cook, p. 33

[13] Cook, p. 33

[14] Cook, p. 33

[15] Cook, p. 33; Yunhuan, p. 22

[16] Cook, p. 33; Yunhuan, p. 22

[17] Yunhuan, p. 22

[18] Yunhuan, p. 22

[19] Yunhuan, p. 22

[20] Yunhuan, p. 22; Cook, p. 33

[21] Yunhuan, p. 22; Cook, p. 33

[22] Yunhuan, p. 22; Cook, p. 33

[23] Yunhuan, p. 22

[24] Yunhuan, p. 22

[25] Yunhuan, p. 22

[26]Yunhuan, p. 22

[27]Yunhuan, p. 22

[28] Yunhuan, p. 22

[29] Yunhuan, p. 22

[30]Yunhuan, p. 22

[31] Yunhuan, p. 22

[32] Yunhuan, p. 22

[33] Cook, p. 34

[34] Cook, p. 34

[35] Cook, p. 34

[36] Yunhuan, pp. 22-23

The post Queen Jiangshi – The Kingmaker appeared first on History of Royal Women.