Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 167

September 19, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Her first speech from the throne

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands’ first official act after all the inauguration celebrations was her speech from the throne on Prinsjesdag (Literal translation: Little Prince’s Day) on 20 September 1898. During Queen Wilhelmina’s minority, her mother had handled the speech from the throne. Queen Wilhelmina had attended the 1897 speech from the throne with her mother, and after the end of her regency, Queen Emma still often joined her daughter for the speech.

Prinsjesdag is the day on which the reigning monarch addresses a joint session of the Dutch Senate and House of Representatives to set out the main government policies for the coming parliamentary session. The assembly of the States-General usually takes places in the Ridderzaal (Knight’s Hall) though during Queen Wilhelmina’s early reign it was held in the assembly room of the House of Representatives as the Ridderzaal was being renovated.

Embed from Getty Images

The glass coach

Embed from Getty Images

The golden coach

Queen Wilhelmina had received a Golden Coach for her inauguration, and although this became the traditional coach to use during Prinsjesdag later (not currently, as it’s being renovated), it was first used for Prinsjesdag in 1903. Before this, Queen Wilhelmina used the Glass Coach. Queen Wilhelmina missed just four years in total. In 1908 and 1909, she was pregnant and subsequently gave birth to Princess Juliana and was thus absent. In 1911, she was annoyed with the Speaker of the House of Representatives as he did not withdraw from his post as she wished him to do and subsequently refused to hold the speech. She was ill in 1947. If the monarch is not available, the speech is held by a member of a commission on behalf of the monarch.

Queen Wilhelmina and Queen Emma travelled together in the Glass Coach through The Hague for her first Prinsjesdag. To give as many people as possible the chance to see them, the way back was a bit longer. While Queen Emma was dressed in black velvet, Queen Wilhelmina wore a white satin dress with silver embroidery. She also wore the ribbon of the Order of the Netherlands Lion. She also wore a small hat with three curled feathers. When her six-minute speech was over, the attendees cheered, “Long live the Queen!” and “Long live the Queen Mother!” Once the two Queens were back at Noordeinde Palace, they showed themselves in the window to the public.1

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Her first speech from the throne appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 18, 2020

Book News October 2020

Queen of Versailles: Madame de Maintenon, First Lady of Louis XIV’s France

Hardcover – 22 October 2020 (US & UK)

The rise to power of Françoise d’Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon (1635-1719), a queen in all but name, was nothing short of extraordinary. Born into poverty and ignominy, she used her intellect, charisma, and connections to join the ranks of fashionable society, eventually establishing herself at the French Court as governess to the legitimized children of Louis XIV. Her relationship with the Sun King gradually flourished, and after the death of the queen in 1683, the couple secretly married. Although their marriage was never made public, Maintenon came to wield unparalleled influence as Louis XIV’s closest confidante and most trusted political adviser. The ageing king required her daily presence in governmental meetings and relied on her for advice on crown appointments, state business, and policymaking. Her modest suite of apartments at Versailles became the heart of the Court, and she was pursued by officials and dignitaries, popes and princes from across Europe, all anxious to appropriate her influence. She used her expansive social network to intervene in a range of political, religious, and royal family affairs, but not always with the king’s knowledge, and her successes were often outweighed by controversy and failure. In Queen of Versailles, Mark Bryant explores the remarkable life and court career of Madame de Maintenon. A study in queenship, it reveals how the dynamics of power and gender operated within the realms of early modern high politics, church-state affairs, and international relations while providing unique insights into the Sun King and his Court.

Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World

Paperback – 13 October 2020 (US & UK)

Sister of Caligula. Wife of Claudius. Mother of Nero. The story of Agrippina, at the centre of imperial power for three generations, is the story of the Julio-Claudia dynasty—and of Rome itself, at its bloody, extravagant, chaotic, ruthless, and political zenith.

In her own time, she was recognized as a woman of unparalleled power. Beautiful and intelligent, she was portrayed as alternately a ruthless murderer and helpless victim, the most loving mother and the most powerful woman of the Roman empire, using sex, motherhood, manipulation, and violence to get her way, and single-minded in her pursuit of power for herself and her son, Nero.

This book follows Agrippina as a daughter, born in Cologne, to the expected heir to Augustus’s throne; as a sister to Caligula who raped his sisters and showered them with honours until they attempted rebellion against him and were exiled; as a seductive niece and then wife to Claudius who gave her access to near unlimited power; and then as a mother to Nero—who adored her until he had her assassinated.

Through senatorial political intrigue, assassination attempts, and exile to a small island, to the heights of imperial power, thrones, and golden cloaks and games and adoration, Agrippina scaled the absolute limits of female power in Rome. Her biography is also the story of the first Roman imperial family—the Julio-Claudians—and of the glory and corruption of the empire itself.

She is But a Woman: Queenship in Scotland 1424–1463

Paperback – 6 October 2020 (US) & 6 August 2020 (UK)

She is But a Woman, the first in-depth study of medieval Scottish queens, investigates the relationship between gender and power in the medieval Scottish Court by exploring the art of queenship as practised by Joan Beaufort and Mary of Guelders, queens of James I and James II. These women were excluded from authority but clearly possessed power as wives and mothers of kings. They established and cultivated relationships with members of the Court, learned about Scottish political life and supported their husbands in the business of government. The book examines for the first time the arrivals of Joan and Mary in Scotland, their social and political status, their relationships with their husbands and families, and their roles in international diplomacy.

This modern re-evaluation of the role and power of the medieval queen is a thematic exploration rather than a biographical study. It situates the experiences of Joan and Mary within a broader European context and provides a new perspective on Scotland’s political, social and cultural links with Europe in the fifteenth century.

The Tsarina’s Lost Treasure: Catherine the Great, a Golden Age Masterpiece, and a Legendary Shipwreck

Hardcover – 1 September 2020 (US) & 15 October 2020 (UK)

On October 1771, a merchant ship out of Amsterdam, Vrouw Maria, crashed off the stormy Finnish coast, taking her historic cargo to the depths of the Baltic Sea. The vessel was delivering a dozen Dutch masterpiece paintings to Europe’s most voracious collector: Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia. Among the lost treasures was The Nursery, an oak-panelled triptych by Leiden fine painter Gerrit Dou, Rembrandt’s most brilliant student and Holland’s first international superstar artist. Dou’s triptych was long the most beloved and most coveted painting of the Dutch Golden Age, and its loss in the shipwreck was mourned throughout the art world.

Princess Mary, Princess Royal, Countess of Harewood

Hardcover – 7 October 2020 (Worldwide)

Born in 1897, Princess Mary was the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary. Despite her Victorian beginnings, she strove to make a princess’ life meaningful, using her elevated position to help those less fortunate and defying gender-based conventions about a woman of her standing should be able to do. From her heavy involvement in the war effort, visiting wounded soldiers and training as a nurse, to her role in many of the 20th century’s key events in royal history, Mary was one princess who paved the way for the modern age.

Nefertiti, Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt: Her Life and Afterlife

Hardcover – 6 October 2020 (US) & 10 October 2020 (UK)

During the last half of the fourteenth century BC, Egypt was perhaps at the height of its prosperity. It was against this background that the “Amarna Revolution” occurred. Throughout, its instigator, King Akhenaten, had at his side his Great Wife, Nefertiti. When a painted bust of the queen found at Amarna in 1912 was first revealed to the public in the 1920s, it soon became one of the great artistic icons of the world. Nefertiti’s name and face are perhaps the best known of any royal woman of ancient Egypt and one of the best-recognized figures of antiquity, but her image has come in many ways to overshadow the woman herself.

Nefertiti’s current world dominion as a cultural and artistic icon presents an interesting contrast with the way in which she was actively written out of history soon after her own death. This book explores what we can reconstruct of the life of the queen, tracing the way in which she and her image emerged in the wake of the first tentative decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs during the 1820s–1840s, and then took on the world over the next century and beyond.

All indications are that her final fate was a tragic one, but although every effort was made to wipe out Nefertiti’s memory after her death, modern archaeology has rescued the queen-pharaoh from obscurity and set her on the road to today’s international status.

The Windsor Diaries: A Childhood with the Princesses

Kindle Edition – 8 October 2020 (US)

Hardcover – 8 October 2020 (UK)

Alathea’s home life was an unhappy one. Her parents had separated, and so during the war, she was sent to live with her grandfather, Viscount Fitzalan of Derwent, at Cumberland Lodge in Windsor Great Park. There Alathea found the affection and harmony she craved as she became a close friend of the two princesses, visiting them often at Windsor Castle, enjoying parties, balls, cinema evenings, picnics and celebrations with the Royal Family and other members of the Court.

Alathea’s diary became her constant companion during these years as day by day she recorded every intimate detail of life with the young Princesses, often with their governess Crawfie, or with the King and Queen.

Written from the ages of sixteen to twenty-two, she captures the tight-knit, happy bonds between the Royal Family, as well as the aspirations and anxieties, sometimes extreme, of her own teenage mind.

These unique diaries give us a bird’s eye view of Royal wartime life with all of Alathea’s honest, yet affectionate judgments and observations – as well as a candid and vivid portrait of the young Princess Elizabeth, known to Alathea as ‘Lilibet’, a warm, self-contained girl, already falling for her handsome prince Philip, and facing her ultimate destiny: the Crown.

The Little Princesses: The Story of the Queen’s Childhood by Her Nanny, Marion Crawford

Paperback – 27 October 2020 (US & UK)

Originally published in 1950, The Little Princesses was the first account of British Royal life inside Buckingham Palace as revealed by Marion Crawford, who served as governess to princesses Elizabeth and Margaret.

A twenty-two-year-old teacher recruited to look after the Duke and Duchess of York’s young daughters in 1931, Marion Crawford―affectionately known as “Crawfie” by her charges―spent sixteen years with the Royal family as the children’s governess. From King Edward VIII’s abdication of the throne in order to marry American divorcée Wallis Simpson and King George VI’s subsequent crowning, through World War II, and all the way to Elizabeth’s courtship and marriage to Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Crawfie’s memoir offers an intimate and revelatory perspective of Elizabeth and Margaret’s childhood during one of the most momentous eras in British history.

Diaries of an Egyptian Princess

Hardcover – 15 October 2020 (UK) & 14 April 2020 (US)

Princess Nevine Halim is a direct descendant of the royal family that ruled Egypt from 1805 until the abdication of King Farouk in the wake of the Free Officers coup in 1952. The eldest of three children, she was born in Alexandria on 30 June 1930, the great-great-granddaughter of Muhammad Ali Pasha on her father’s side and the great-granddaughter of Khedive Ismail on her mother’s side.

Drawing on her own diary, as well as those of her mother and grandmother, she takes us on a journey from the First to the Second World War, from Egypt to Europe and the United States, from a world of glamour, wealth, and privilege to the fugitive existence of the exile and social outcast after 1952. We also meet her father, Abbas Halim, the charming rebel prince who clashed with King Fuad for championing the rights of workers, as well as many other members of the Egyptian royal family and a glittering host of international royals, politicians, and film stars.

Packed with royal gossip and political intrigue, with tales of young love and fashionable society, and of princes and princesses dancing perilously close to the edge of a way of life that would one day fall apart and then vanish, Diaries of an Egyptian Princess is an event-filled account of an endlessly fascinating epoch in modern Egyptian history.

Domina: The Women Who Made Imperial Rome

Paperback – 20 October 2020 (US) & 22 September 2020 (UK)

Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—these are the names history associates with the early Roman Empire. Yet, not a single one of these emperors was the blood son of his predecessor. In this captivating history, a prominent scholar of the era documents the Julio-Claudian women whose bloodline, ambition and ruthlessness made it possible for the emperors’ line to continue.

Eminent scholar Guy de la Bédoyère, author of Praetorian, asserts that the women behind the scenes—including Livia, Octavia, and the elder and younger Agrippina—were the true backbone of the dynasty. De la Bédoyère draws on the accounts of ancient Roman historians to revisit a familiar time from a completely fresh vantage point. Anyone who enjoys I, Claudius will be fascinated by this study of dynastic power and gender interplay in ancient Rome.

The post Book News October 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 17, 2020

Isabel Neville – The forgotten Duchess

Isabel Neville was born on 5 September 1451 at Warwick Castle as the elder daughter of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (the Kingmaker), and Anne de Beauchamp, 16th Countess of Warwick in her own right. She was joined in the nursery by a younger sister named Anne (later Queen as the wife of King Richard III) on 11 June 1456. The girls had a mini-establishment, away from their parents, headed by a governess.

The family relocated to Calais in 1457 as Isabel’s father had been appointed as Captain of Calais. Her father was deeply involved in the Wars of the Roses, and it would change the sisters’ life forever. Around 1464, the Neville family packed up their bags and planned to return to England permanently with the Yorkist King Edward IV in power. For the next few years, Isabel’s base was Middleham Castle, and she and her sister may have attended key events at court. Anne and Isabel received a traditional upbringing for girls of that time. Isabel and her family were certainly present for the christening of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville’s first child, Elizabeth of York, in 1466.

On 12 July 1469, Isabel married the younger brother of King Edward IV – George, Duke of Clarence – at Calais. The wedding was undoubtedly also attended by the bride’s parents, and possibly even the groom’s mother, Cecily. This meant that Isabel was now a royal Duchess, but her father and her new husband planned to remove King Edward IV from the throne, but it all went belly up. Isabel had fallen pregnant shortly after the wedding, and she went into labour as they fled to Calais, but their ship was denied entry to the harbour. Tragically, the child was stillborn on 17 April 1470 as Isabel was denied the help of a midwife and had only her mother to help her. Sources differ on the sex of the child and it was either taken ashore at Calais or was buried at sea. They were finally able to disembark at Normandy on 1 May. The Duke of Clarence managed to reconcile with the King and Isabel took up her place at court as the second lady of the land.

However, her father was still not ready to concede and sided with Queen Margaret, the wife of King Henry VI who had been deposed by King Edward IV. She and her son Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, were in France, waiting for their chance. Isabel’s sister Anne was duly betrothed to Edward on 25 July 1470 before finally being married sometime in December. The invading forces returned to England the following April, having been held back by storms. Isabel’s father was killed in battle that same April and her mother fled into sanctuary. Edward of Westminster was killed in battle as well, making Anne a widow at the age of 14. Anne was eventually released into the custody of her sister and the Duke of Clarence.

It soon became apparent that Richard, the Duke of Gloucester, Edward and George’s younger brother, was interested in marrying Anne but the Duke of Clarence would have none of it. Their courtship may have been romantic, or it was all calculated, we simply don’t know. On 16 February 1472, Anne fled from her sister’s household and into sanctuary at the London collegiate church of St Martin-le-Grand. She remained there until July waiting for the dispensation to arrive. Their wedding was probably celebrated that summer, but we don’t have an exact date.

The Duke of Clarence was granted Isabel’s part of the Warwick inheritance in return for his defection back to King Edward. They would have preferred not to see Anne marry again, in order to keep the entire inheritance. Conveniently, their mother – still in sanctuary – was declared legally dead in order to divide the inheritance. On 14 August 1473, Isabel gave birth to her second child, a daughter named Margaret. On 25 February 1475, she gave birth to her third child, a son named Edward. It wasn’t long before she was pregnant with her fourth child, and on 6 October 1476, she gave birth to a second son, named Richard. Tragically, little Richard would die just three months later.

Isabel herself would not see the new year. Though it is unclear what she died of exactly, Isabel died on 22 December 1476. Her husband accused one of her ladies-in-waiting of her murder the following April. Ankarette Twynho was suspected of poisening Isabel by giving her “a venomous drink of ale mixed with poison.”1 In a single day, Ankarette was tried, indicted and hanged. She was pardoned by King Edward IV, though poor Ankarette was no less dead by it.

Isabel, Duchess of Clarence, was buried behind the high altar of Tewkesbury Abbey, where she would be joined not much later by her husband, after his execution for treason. Their children were taken into the household of Isabel’s sister Anne. Tragically, their father’s fate would be their own. Both eventually ended up on the scaffold.2

The post Isabel Neville – The forgotten Duchess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 15, 2020

Lambertikirche in Oldenburg – A mix of old and new

The Lambertikirche in Oldenburg has a long history. A settlement was first recorded there in 1108, though no mention was made of a church at that time. A church was first mentioned in 1237, and this church was dedicated to St Lambertus between 1155 and 1234. During medieval times, the church was surrounded by a cemetery. In the 18th century, the church was rebuilt in the neo-classical style with the inside being made into a rotunda and the cemetery was closed.

Countess Margrethe Hedevig and Count Christian Friedrich von Haxthausen have two magnificent marble sarcophagi in the vestibule of the Lambertikirche. Christian Friedrich was a descendant of Anthony Günther, Count of Oldenburg, through an illegitimate line. He served as chamberlain of the Danish Queen Charlotte Amalie (born of Hesse-Kassel) for several years. His wife too was at the Danish court as she was a governess of the future King Frederick V’s children.

The other two coffins belong to Sophie Katharina of Schleswig-Holstein-Sønderborg and her husband Anthony Günther, Count of Oldenburg, his cenotaph close by is thus empty. The two cenotaphs and the two coffins of Sophie Katharina Anthony Günther were moved to the vestibulum in 2009. The two coffins are original.

The church supposedly also has a crypt, though I was unable to find an entrance to it. This may have been lost during the extensive renovations.

Click to view slideshow.

The church is open for visitors every day except Sunday.

The post Lambertikirche in Oldenburg – A mix of old and new appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 14, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The short life of Prince Maurice

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands would never know any of elder half-brothers. The first of them to die was Prince Maurice, whose life was cut short by disease.

Prince Maurice was born on 15 September 1843 in The Hague as the second son of the future King William III of the Netherlands and his first wife, Sophie of Württemberg. William delivered the news to his father King William II in person and called himself, “the happiest man in the world.”1 He looked to be stronger and bigger than his elder brother – another William – but he soon turned out to be rather sickly. Maurice was a calm and friendly child, and his mother lived in constant worry over his delicate health. This was in no way helped by the death of young Prince Frederick, the ten-year-old son of her husband’s uncle – also named Frederick- and Louise of Prussia. Sophie wrote, “I am so sad, so sad; if something like that happened to me, by God, I hope I will also die. Of course, I am receiving no one. Our mourning will last for weeks. The funeral is next Wednesday or Thursday. I keep walking to my children, to see, to hear, to feel that they are alive.”2

The governor of Maurice’s elder brother wrote of the two brothers in 1849, “While W. is always sullen, rude and unkind, M., on the other hand, is politeness and kindness itself. His health is very delicate, as a consequence of bad living. The conclusion must be that both their educations have been miserable, though W.’s character has been damaged the most.”3

In May 1850, Maurice became ill yet again. Sophie had lost all faith in the court doctor Everard and called for another doctor, named Ter Winkel. He diagnosed an “unclean stomach” and administered several medications, including musk. Maurice’s father had no faith in the medicines or the doctor. Doctor Everard was eventually called, and he diagnosed a “nervous illness with the beginnings of meningitis.” Ter Winkel laughed the diagnosis away and told Sophie that there was no danger whatsoever. Sophie’s husband angrily told Ter Winkel to leave at once. As Maurice’s condition deteriorated, William called for two more doctors, Van Bylandt and Vinkhuyzen.

It was too late for young Maurice. Sophie often dragged young William to his brother’s bed, against the will of the doctors and her husband. On 4 June, around 5 in the afternoon, she had taken him to see his brother once more, but he was taken away by his governor. Despite his illness, Maurice recognised the governor and said, “Hello, sir” in a hoarse voice. Just 15 minutes later, they learned that Maurice had passed away. Sophie would never forgive herself for bringing in Ter Winkel, and her friend Lady Malet admitted that Sophie was never happy again. She wrote, “Always running from herself. A never-ending torture.”4

Maurice was just six years old when he died. On 10 June 1850, he was interred in the royal crypt in Delft.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The short life of Prince Maurice appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 13, 2020

Queen Elizabeth I – The years of waiting (Part two)

Roger Ascham replaced William Grindal as Elizabeth’s tutor when William died in 1548, and he remained as her full-time tutor for about two years. After this period, he continued to teach her, but it was not on a daily basis. After she became Queen, he wrote of her, “From the age of 16, she was unsurpassed in gravity for her age, and in a cheerful alacrity of mind that was wonderful to behold.”1 Her brother sometimes invited her and Mary to court, though Mary was regarded with suspicion by Edward. Elizabeth and Edward wrote to each other rather infrequently, but their relationship was considered to be good. From time to time, suitors for her hand in marriage were considered, but none ever came to fruition.

When Elizabeth’s brother King Edward VI fell ill in early 1553, speculation about the succession began, but Edward had already made up his mind, and he settled the succession on his first cousin once removed, the 16-year-old Lady Jane Grey, daughter of Frances Brandon, who in turn was the daughter of Mary Tudor, the sister of King Henry VIII. He, therefore, excluded both his half-sisters but also the entire line of Henry’s elder sister Margaret, who had married the King of Scots. Edward died on 6 July 1553, and during the following turbulent days, Elizabeth kept her head down. Once Lady Jane Grey was deposed, and Mary had succeeded as Queen Mary I, Elizabeth wrote at once to congratulate her half-sister and to ask about court mourning for their brother. On 31 July 1553, she met Mary in London, and they had an outwardly cordial meeting. Mary began to use the catholic religion as a test of loyalty, and Elizabeth did not go to mass. For now, Mary declared that she had no intention to coerce anyone’s conscience but that she wished people would “charitably embrace the same”2, but it was always her intention to restore the catholic faith. Elizabeth’s diplomatic side came out, and she realised that if she wanted to survive, she would have to do something. So, she asked for instruction in the catholic faith. Nobody appeared to be entirely convinced by Elizabeth’s actions, but for now, Mary had no reason to act against her sister.

At the end of the year, Elizabeth asked to leave the court, and surprisingly, Mary agreed to let her leave. In January 1554, Elizabeth wrote to Mary to congratulate her on her upcoming marriage to Philip of Spain, but she also complained of a heavy cold. Nevertheless, Mary summoned Elizabeth back to court, and she nearly had to be dragged there. During this time Wyatt’s Rebellion took place, intending to place Elizabeth on the throne instead of Mary. One of those involved was Lady Jane Grey’s father, and although Mary had initially intended to spare Jane’s life, she now had no other choice. Jane’s father and 90 other rebels were executed, as were Jane and her husband. For a while, everything around Elizabeth remained silent, but she was finally arrested on 17 March 1554. She begged permission to write to Mary, and this letter became known as the Tide letter as it caused the group to miss the tide that night to transfer Elizabeth to the Tower. Elizabeth wrote, “I am by your council from you commanded to go unto the Tower, a place more wonted for a false traitor than a true subject… And to this present hour, I protest afore God (who shall judge my truth whatsoever malice may devise) that I never practised, counselled, nor consented to anything which might be prejudicial to your person any way or dangerous to the state by any mean.”3 The following morning, Elizabeth arrived in the Tower. She initially did not want to leave the boat but when she was finally persuaded, she proclaimed, “Here landeth as a true a subject, being prisoner, as ever landed at these stairs.”4 She then sat on the stairs by the river in defiance until one of the servants broke down. She told him, “She knew her truth to be such that no man would have cause to weep for her.”5 She was questioned inside the Tower but she admitted to nothing.

By May, it was decided to send Elizabeth to the country under house arrest. On 19 May – the anniversary of her mother’s execution – Elizabeth left the Tower for Woodstock in Oxfordshire. While there, Elizabeth became bored and frustrated and took out her anger on Sir Henry Bedingfield, who was to watch her. She was sometimes allowed to write to Mary and she used these letters to convince her of her innocence. However, Mary either ignored her letters or replied via Sir Henry. On 7 April 1555, Elizabeth was brought to the court where Mary believed she was pregnant and was soon to have a child. A child was not born, and it appeared that Mary had suffered a false pregnancy. The question of what to do with Elizabeth remained, and on 4 August, Elizabeth was allowed to retire to Ashridge where she remained quiet. The following year, Mary had another false pregnancy. At the end of 1556, the relationship between Mary and Elizabeth seemed to improve somewhat, but at the end of the year, Elizabeth was sent back to Hatfield. In February 1558, Elizabeth spent some time with Mary at Somerset House.

Mary became ill in September though nobody thought it was serious at first. By the end of October, it was clear that it was quite serious. Elizabeth’s response was not recorded but considered the speed with which she set up her government; she was probably planning for it already. Mary remained silent on the subject of the succession throughout these months. A codicil added to her will left the throne “to the next heir by law.” On 7 November, she named Elizabeth as her heir, and she died on 17 November at the age of 42. Elizabeth was proclaimed Queen that same morning. While kneeling, Elizabeth quoted, “This is the doing of the Lord; and it is marvellous in our eyes.”6 She had survived to become Queen; now, she needed to stay Queen.

Part three coming soon.

The post Queen Elizabeth I – The years of waiting (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 11, 2020

Constance of Castile – Claimant to the Castilian throne

Constance was born in 1354 as the daughter of Peter, King of Castile and León and María de Padilla. The Infanta was born into a strange family dynamic- her parents had been married but in secret. The young king was under the control of his mother during this period, and he was coerced into denying he ever married María in order to marry Blanche of Bourbon instead. The relationship between Peter and Blanche was unsuccessful, however, and he kept María as his mistress for many years, having four children with her in total. The eldest child was Beatrice who became a nun, followed by Constance, then a sister Isabella who became Duchess of York and finally a son Alfonso who died as an infant. While Constance was technically illegitimate, she was not treated as such and was named as her father’s heir after the death of her brother.

As with many medieval princesses, we have little detail of Contance’s childhood, and we next hear of her at the time of her marriage when she was around sixteen years old. Constance’s marriage came about after a drawn-out period of war; her father had been involved in wars with Aragon from 1356, and then the Castilian Civil War also began in 1366. During this period, King Peter was known as a cruel ruler and was eventually overthrown by his half-brother Henry of Trastámara. In order to see himself restored to the throne, Peter and his daughters fled and Peter sought aid from Edward, the Black Prince who was the son of King Edward III of England. Luckily for Peter, Edward, the Black Prince agreed to help and decided to take his brother John of Gaunt into battle with him. It is said that Constance and her sister Isabella were given over to the English as collateral for huge loans that King Peter had taken out and would not be able to pay back.

The Black Prince and John of Gaunt helped Peter to defeat his usurping brother Henry. Peter was briefly restored to his throne, but the English princes then backed out of the war due to lack of payment. Ultimately after a long, complicated war, King Peter was killed by his half-brother Henry who claimed the throne of Castile for himself, ignoring Constance’s claim. Constance and her sister Isabella were still in English hands and were placed into dynastic marriages- Constance would marry John of Gaunt and Isabella would marry Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York. Both of these marriages were to sons of King Edward III and were suitable matches considering the girls were daughters of a deceased former king, but the teens must have been afraid of what lay ahead; being sent to England into marriages in order to pay off old debts.

Constance, the ‘de jure’ Queen of Castile, married the recently widowed John of Gaunt on 21 September 1371; the wedding took place in Roquefort, France. It was not until the following year that Constance travelled to England where she was given a ceremonial entry befitting the rank of a Queen – despite her not really being a Queen. Constance was escorted by her brother-in-law Edward, the Black Prince, and her ambitious new husband John started to go by the title of King of Castile and León.

Constance of Castile (public domain)

Constance of Castile (public domain)Shortly after his marriage to Constance, John began an affair with a woman called Katherine Swynford. This affair lasted for decades, and it seems that Constance was forced to accept her husband’s relationship with Katherine. In the following years, Constance gave birth to a son named John and a daughter named Catalina or Catherine. Baby John only lived for a year, but Catalina survived the perils of medieval childhood.

Ever since his marriage to Constance, John of Gaunt had aimed to truly claim his wife’s lands in Castile and the Castilian crown, but due to lack of funds, he could do little but sit and wait. His opportunity finally came in 1386 when England and Portugal became allies. The treaty was formalised when John of Gaunt’s eldest daughter Philippa married John, the King of Portugal. The new allies soon requested aid in a succession crisis and John headed out to assist King John of Portugal. The son of Henry of Trastámara, also named John was trying to take the Portuguese throne too, and the Portuguese king needed assistance.

John of Gaunt travelled into Galicia, Castile with over 5000 men and his whole family. It seemed he might actually take the throne of Castile after all. However, the Castilians mostly refused to engage in battle, and John was lacking in finances for prolonged warfare. His troops were left starving and scavaging for food. Due to the terrible conditions, many soldiers and friends of John died or fled, and he was forced to sign a treaty with John of Trastámara. The Castilian king agreed to pay a large sum each year to John of Gaunt as long as John renounced his claims to the throne of Castile for good, this was agreed, and Catalina, the daughter of Constance and John, was given in marriage to John of Trastámara’s son Henry, meaning that at least Constance’s daughter would one day be the Queen of Castile.

On 24 March 1394, Constance passed away at Leicester Castle. She was buried in Newark Abbey. Following her death, John of Gaunt married his mistress Katherine Swynford, and their children were legitimised- this line led to the birth of King Henry VII of England whereas Catalina of Castile’s line would lead to the birth of Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England, both hugely important figures in European history, without the marriage of John of Gaunt and Constance of Castile, British history could be very different!

The post Constance of Castile – Claimant to the Castilian throne appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 10, 2020

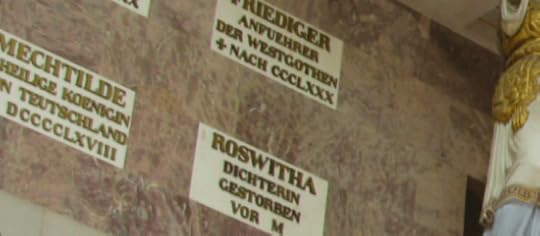

The six royal women of the German Walhalla Memorial

The Walhalla Memorial is a hall of fame that honours distinguished people in German(-speaking) history. It is named for the Valhalla of the Norse Paganism and was begun in 1807 by the future King Ludwig I of Bavaria. The grand hall sits above the Danube River in Donaustauf. With over 2,000 years of history and over 200 busts and plaques, new additions are still being made.

There are six royal women pictured inside the Walhalla Memorial. If there was no known image of the subject at the time, they only received a plaque. If there was a known image, a bust was made.

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

(public domain)

(public domain)Born on 7 July 1207 as the daughter of King Andrew II of Hungary and Gertrude of Merania, she married Louis IV, Landgrave of Thuringia at the age of 14. They had three children together before Louis’ untimely death in 1227. Her brother-in-law became the regent of her minor son and Elizabeth left the court and moved to Marburg. She had a hospital built there for the poor and sick with the money from her dowry and she helped care for the patients herself. After her death in 1231 at the age of 24, miracles were reported at her grave. She was canonized by Pope Gregory IX on 24 May 1235.

Elisabeth’s plaque – By DALIBRI – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Elisabeth’s plaque – By DALIBRI – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsMatilda of Ringelheim

(public domain)

(public domain)Born circa 892, Matilda of Ringelheim married Henry the Fowler, future Duke of Saxony and King of East Francia, in 909. They went on to have five children together before his death in 936. He was buried in Quedlinburg where Matilda founded a convent later that same year. Quedlinburg Abbey became an important religious settlement and its abbesses, including her own granddaughter also named Matilda, enjoyed great prestige. The elder Matilda led the convent for 30 years before she passed it on to her granddaughter. She died after a long illness on 14 March 968 and she was also buried in Quedlinburg. She was known to have been extremely pious and charitable and she was canonised on an unknown date, possibly by acclamation.

By Michael J. Zirbes (Mijozi) – Own work, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Michael J. Zirbes (Mijozi) – Own work, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsTheudelinde/Theodelinda

(public domain)

(public domain)Theudelinde was born circa 570 as the daughter of Garibald I, Duke of Bavaria and Walderada. She was Queen of the Lombards twice as the wife of consecutive rulers Autari and Agilulf. She also acted as regent during the minority of her son Adaloald. She managed to convince her first husband to convert to Christianity and her son with Agilulf was allowed to be baptised a Catholic.

She died in 628.

By Bärwinkel,Klaus – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Bärwinkel,Klaus – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsCountess Amalie Elisabeth of Hanau-Münzenberg

(public domain)

(public domain)Born on 29 January 1602 as the daughter of Philip Louis II, Count of Hanau-Münzenberg and Countess Catharina Belgica of Nassau, Amalie Elisabeth married the future William V, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel in 1619. He was often away on campaign and Amalie Elisabeth acted as regent of Hesse-Kassel. After her husband’s death in 1637, she also acted as regent for their son during a particularly volatile situation. She had significant influence over the eventual Peace of Westphalia.

She died on 8 August 1651.

By Reinhard Dietrich – Own work, CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Reinhard Dietrich – Own work, CC0 via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

(public domain)Born Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst on 2 May 1729, she married the future Emperor Peter III of Russia in 1745. Shortly after his accession, she seized power from him and ruled in her own right for 34 years.

By Marie Čcheidzeová – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Marie Čcheidzeová – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsMaria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress

(public domain)

(public domain)Born on 13 May 1717 as the eldest surviving child of Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor and Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, she ruled the Habsburg lands in her own right and became Holy Roman Empress by right of her husband Francis of Lorraine, who was elected in 1745.

By Marie Čcheidzeová – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

By Marie Čcheidzeová – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe post The six royal women of the German Walhalla Memorial appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Spanish Princess Season 2 trailer released

The Spanish Princess will return for its second season on 11 October 2020. Watch the trailer below.

The post The Spanish Princess Season 2 trailer released appeared first on History of Royal Women.

September 8, 2020

Alexandra of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha – Queen Victoria’s granddaughter (Part two)

Alexandra quickly fell pregnant, and her sister Marie was writing about it as early as August 1896. “She is very quiet about it and seems pleased. Elli and I have concluded that Sandra will have a boy, I wonder if we will be right.”1 Alexandra’s mother travelled to Langenburg in March to be with her and found her daughter already in early labour. Her water broke the following morning, and her first son – named Gottfried – was born later that evening. Her mother wrote to Marie, “The little creature was beginning to open his eyes the moment his head was born, and he was hardly out, then he yelled quite tremendously, and Sandra said that she felt him even kicking at her. She looked most surprised, and when I exclaimed “a son” poor Erni quite broke down and sobbed violently.”2 Alexandra nursed him herself for a time, despite having hired a wetnurse.

In July, Marie wrote of Alexandra and her grandson, “I found her looking blooming and very gay in fact she really looks like 15, has a very good figure, wears her trousseau dresses (which is always a triumph) and is quite mad about her baby. It is a very sweet little thing, a pretty baby, not big, but most appetising and extremely good and amiable. One can quite enjoy it, as the little creature is always smiling and looks most placid.”3 Alexandra had been glad to get away from Langenburg for a little bit as she thought Langenburg dull with her parents-in-law. A daughter named Marie Melita was born on 18 January 1899. Three more children were born over the years; Alexandra (born 2 April 1901), Irma (born 4 July 1902) and the shortlived Alfred (born and died 1911).

Little Alfred was no doubt named for his grandfather and uncle, who died in 1900 and 1899 respectively. Alexandra’s brother Alfred died in unclear circumstances, with rumours ranging from suicide to illness on 6 February 1899. Her mother wrote to Marie in April of that year, “Our poor, poor Alfred! He gave us only pain and trouble and yet one was always hoping for his better future, one was working for him and had an object in life.”4 It also left the succession in doubt and this was eventually settled in favour of the young Charles Edward, Duke of Albany, the only son of Queen Victoria’s youngest son Prince Leopold.

Alexandra’s father was suffering from cancer, and by early 1900 he was undergoing treatments. He died on 30 July 1900 and was succeeded by the underage Charles Edward. The regency was taken up by Alexandra’s husband until 1905. In 1913, Ernst’s father passed away, making Ernst and Alexandra the new Prince and Princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. During the First World War, Alexandra worked as a nurse. Her eldest daughter Marie Melita was the first of her children to marry – to Wilhelm Friedrich, Hereditary Prince of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. She had only just turned 17 years old and gave birth to Alexandra’s first grandchild, Prince Hans, the following year.

Gottfried would marry Princess Margarita of Greece and Denmark, the sister of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, in 1931 but her two other children would remain unmarried. On 1 May 1937, Alexandra joined the Nazi party with her membership number being 4969451.5 Her husband had joined a year earlier and her son Gottfried, and daughters Irma, Maria Melita and Alexandra also joined.

Alexandra had been suffering from ill-health for some years before dying on 16 April 1942 at Schwäbisch Hall at the age of 63. Her husband would outlive her for eight years. She was buried at the Langenburg Familienfriedhof

The post Alexandra of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha – Queen Victoria’s granddaughter (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.