Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 164

October 27, 2020

Arabella Churchill – “Nothing but skin and bones”

Arabella Churchill is a little-known figure in English history; despite her decade-long relationship with James, Duke of York who later became King James II of England. Perhaps attentions were focused on the King at the time, King Charles II, who was James’ brother and a notorious womaniser. With King Charles flaunting his mistresses and showering them with gifts and titles, his brother James’ mistresses were not as well-known at the time and are less written about today.

Arabella Churchill was born in February 1648 to Sir Winston Churchill (from the same family line as the later Prime minister with the same name) and his wife, Elizabeth Drake. Arabella’s family, the Churchills, were devoted royalists who were rewarded for their services once King Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660. Arabella’s father, Winston, was an MP and a court historian, which brought her and her siblings into the inner circle of the royal family. Arabella, the oldest of her four surviving siblings, became a maid of honour to the Duchess of York during the restoration period when she was around seventeen years old.

Living within the household of Anne Hyde, Duchess of York, it was not long before Arabella met Anne’s husband James. James was rather upset at the time as his mistress Margaret Brooke had died suddenly. James had flaunted Margaret as his mistress and taken her to many public events – to the dismay of his wife and Margaret’s husband. John Denham, Margaret’s husband, is said to have been driven insane with anger at his wife’s affair with the Duke, and when Margaret died, rumours circulated that he had murdered her with poisoned hot chocolate! John was never charged for this due to lack of evidence, but the scandal meant that James approached relationships with future mistresses rather differently and was much more discreet.

James, Duke of York (public domain)

James, Duke of York (public domain)It is said that the Duke of York fell in love with Arabella Churchill in 1665 when one day she was out hunting and fell from her horse. Arabella fell to the ground and became concussed, leaving her underwear and legs exposed, her thighs were apparently her best feature and James was immediately smitten. Unlike Margaret Brooke who was known to be one of the great beauties of the age, Arabella was described as “a tall creature, pale-faced and nothing but skin and bone” but she was said to be smart and quick-witted which James preferred to a mistress with nothing but looks. The relationship did seem to bewilder Arabella’s family, however, and they said it was a “joyful surprise that so plain a girl had attained such high preferment”.

Arabella’s hold on the Duke of York must have been based on something more than her legs and her wit as unlike James’ affairs of the past, this relationship lasted for over a decade! The pair were together for seven years of James’ marriage to Anne Hyde and were also still together when James married again after Anne’s death. Both Anne and James’ second wife Mary of Modena hated him having affairs, but somehow his relationship with Arabella persisted, maybe due to her staying out of the limelight. James did provide a home for Arabella, and her brothers did benefit from elevated stations at court, but Arabella lived mostly a quiet, domestic life and did not cause scandal.

Throughout their relationship, Arabella and James had four children together who all survived to adulthood. Their first child was Henrietta FitzJames who went on to marry Henry Waldegrave 1st Baron Waldegrave. Their second child James FitzJames, 1st Duke of Berwick went on to have a very successful military career under the leadership of his father and later King Louis XIV of France. Following James were two more children: Henry FitzJames, 1st Duke of Albemarle and another daughter named Arabella who became a nun. These four children thrived and were well-educated between England and France; this must have been very painful for both of James’ wives; Anne and Mary, who both lost many children and suffered numerous miscarriages.

Catherine Sedley (public domain)

Catherine Sedley (public domain)After Anne Hyde had died in 1671, James married again to the Catholic Mary of Modena. This stunning young wife hated James keeping a mistress so much that she would refuse to eat and tell the priest not to hear James’ confession unless he gave up his mistresses. It was not the power of Mary of Modena; however, which destroyed the relationship between James and Arabella, it was another mistress called Catherine Sedley who had de-throned Arabella by 1678.

After the end of her relationship with James, Arabella was able to provide for herself and her children by selling the home that James had given her for a substantial sum. Arabella then married a man called Charles Godfrey in 1680; he was an army officer and politician. The pair were married for over 40 years and had three children together.

Arabella would have watched her former partner James ascend the throne as King James II and then lose his throne during the Glorious Revolution. She died aged 82 under the reign of King George II after living through the restoration of the monarchy, the Glorious Revolution, and the rise of the Hanoverians to the throne! Through her children James and Henrietta, Arabella Churchill is the ancestor of many notable family lines including the Earls Spencer, making her the eight times great-grandmother of Diana, Princess of Wales. The Dukes of Berwick and the Dukes of Alba are also descended from the children of James II and Arabella Churchill.1

The post Arabella Churchill – “Nothing but skin and bones” appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 25, 2020

Indira Devi – A groundbreaking Maharani

This article was written by Shivangi Kaushik.

Indira Devi was born as Indira Raje on 19 February 1892 to Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad and Maharani Chimna Raje Gaikwad. Her father was the Maharaja (ruler) of Baroda State (present-day Gujarat in India) from 1875 to 1939.

She was the only daughter of her parents, and because of their advanced views on education, she was the first Indian princess to go to school and college. In 1910, when she was 18 years old, her marriage with the Maharaja Scindia of Gwalior was arranged. Gwalior, like Baroda, was one of the most important Maratha states in princely India. The Maharaja of Gwalior was at least twenty years older than the princess and was already married, but he was childless and badly needed an heir. He had met the princess in England, who was by that time, slowly getting to be known for her beauty. He returned to India and sent a proposal of marriage to the Maharaja of Baroda. After due considerations, the proposal was accepted. Thus, Princess Indira Raje was betrothed to the Maharaja of Gwalior… but fate had other plans.

In the year 1911, Indira accompanied her parents to the great Delhi Durbar where the princes and rulers from all over India came to offer their allegiance to the British crown. The Delhi Durbar lasted many days, and it was here that Indira met the younger brother of the Maharaja of Cooch Behar, Prince Jitendra Narayan, and it was love at first sight.

After the Delhi Durbar came to an end, all the princely families returned to their states. By that time, Indira had made up her mind. She did something that was unheard of until that time. Without her parents’ knowledge, she wrote a letter to the Maharaja of Gwalior, saying that she did not want to marry him. In Baroda, the preparations for the wedding were already in full swing. Amidst all this, Indira’s father received a telegram from the Maharaja of Gwalior asking, “What does the princess mean by her letter?”

Indira was immediately summoned and asked to explain. She admitted to writing the letter, and her parents were shocked. In India, an engagement is as binding as a marriage. A broken engagement would lead to scandal and gossip. She was given a thorough lecture on family honour and the disgrace her actions would bring upon her family. However, the letter had already done the damage – there was no question of a marriage.

Indira’s parents were strongly opposed to her marrying the younger brother of the Maharaja of Cooch Behar. Cooch Behar was a smaller, less important state and its royal family was of a different caste and were not Maratha. The Prince was a younger brother of the Maharaja, and he was not expected to inherit the throne.

Apart from this, the Cooch Behar family was highly westernised compared to the Baroda family. All sorts of pressures were put on Indira to forget any plans to marry the young prince. Nevertheless, Indira continued to meet Jitendra in secret. This continued for almost two years. The young prince was even summoned by the Maharaja of Baroda and told in no uncertain terms to not have any delusions about marrying Indira. Indira’s father suspected her of planning to elope, which would result in an even bigger scandal.

Indira’s parents finally agreed to the match but not wholeheartedly. They arranged for the wedding to take place in London at the home of a friend. Finally, in July 1930 Princess Indira married Prince Jitendra Narayan of Cooch Behar. Just three weeks after the wedding Jitendra’s brother died of an illness, and as a result, Prince Jitendra succeeded him as the Maharaja of Cooch Behar and Indira became the Maharani Indira Raje of Cooch Behar.

She and Jitendra would go on to have five children together. Prince Jagaddipendra Narayan – who would succeed his father, Princess Menaka, Prince Indrajitendra, Princess Ila and Princess Gayatri Devi – who would go on to marry the Maharaja of Jaipur. Indira and Jitendra’s married life did not last long as Jitendra died of an illness after just 9 years of marriage. Indira was still only 30 years old when their eldest son was crowned the new Maharaja. He was only seven years old at the time, so Indira became regent. She managed the governing of the princely state with the help of many ministers and councillors until her eldest son was grown enough to take over the responsibilities of the state.

Besides acting as regent for her son, she excelled at decorating and arranging a house; she had an impeccable eye for furniture, fabrics and objects of arts. She could also converse fluently in English, French, Marathi and Bengali. She was considered to be one of the best-dressed women in India. She used to order her chiffons for sarees from a Paris fashion house, which had specially woven fabrics in 45-inch width suitable for sarees. In Delhi and Calcutta, the shops from which she ordered her specific designs were allowed to copy them after one year for other customers. She had a passion for shoes, which were mostly custom made by Ferragamo in Florence. She was known in India and abroad for the excellence of her parties. In a time when being a widow in India meant following an austere life confined to the house and time spent in prayers, she broke the norm. She proved that widowed women could entertain without the company of a husband or a father.

Indira spent a significant part of a year in Europe, mostly in England and France where she would charm the crowds with her beauty and elegance. In the words of her daughter Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur, “Mother was quite simply the most beautiful and exciting woman any of us had known. She remains in my memory as an unparalleled combination of wit, warmth and exquisite looks.”

Nevertheless, Indira faced many tragedies. She lost two of her children; Princess Ila died at a very young age, and Prince Indrajitendra died in an accidental fire. Maharani Indira herself died in Bombay (Mumbai) on 6 September 1968.

The post Indira Devi – A groundbreaking Maharani appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 24, 2020

Louise Henriette of Nassau – A sold Princess

Louise Henriette of Nassau was born in The Hague on 7 December 1627 as the eldest daughter of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, and Amalia of Solms-Braunfels. She spent her youth at the court in The Hague, where she grew up with her siblings. She also spent a lot of time with the daughters of Elizabeth Stuart, the Winter Queen of Bohemia, who were in exile at the court of The Hague. She developed a life-long friendship with their eldest daughter, Elisabeth of the Palatinate. Louise Henriette’s elder brother, William II, Prince of Orange, would become the father of King William III of England, Ireland and Scotland.

When her brother William married Mary, Princess Royal, the daughter of King Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria of France, prospects were raised for Louise Henriette as well. A match with Henry Casimir I of Nassau-Dietz was vetoed by her mother who had set her sights higher. A match was found in the form of the Great Elector – Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg. However, Louise Henriette was in love with someone else – her cousin Henri Charles de La Trémoille, Prince of Talmant. They wrote letters to each other which were found by her mother, who had broken into Louise Henriette’s desk. She read the letters to her husband to convince him of the unsuitability of the match with Henri Charles. Louise Henriette could protest all she liked, but her wedding to Frederick William was being planned with or without her. She wrote, “It is to my regret that I, for money’s sake and so little land, am to be so unhappy and to be sold. Oh, I wish I was dead, or I wish I were a peasant so that I could take someone to my liking.”1

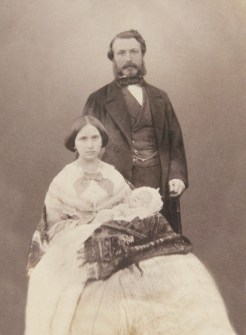

Louise Henriette and her husband (public domain)

Louise Henriette and her husband (public domain)On 7 December 1646, Louise Henriette married Frederick William in Noordeinde Palace – it was also her 19th birthday. By then, her father was seriously ill, and he would die just four months later. According to the Henri Charles’ memoirs, her father told her on his deathbed that he regretted forcing her to marry the Elector.2 The newlyweds spent their first years as husband and wife in Cleves, which was part of the Electorate of Brandenburg. During those two years in Cleves, Louise Henriette got to know her husband and a mutual appreciation began to grow between them. Her first child, a son named William Henry, was born to them in Cleves but he died during their move to Berlin in 1648. In her grief, Louise Henriette could travel no further, and she stayed behind in Tanggermünde until her husband came to fetch her personally. The arrival in war-torn Berlin gave Louise Henriette the inspiration she needed, and she threw herself into improvements for the city. She even hired a Dutch builder to renovate the Electoral Palace. She also received a hunting lodge from her husband which she turned into Oranienburg Palace. She introduced the first potatoes as cheap food for the people and founded schools for farming and schools for women and girls.

It began to look like Louise Henriette would have no more children, and she vowed to found an orphanage if she would only have a child. In her despair, she even offered her husband a divorce so he could marry again and father an heir. He adamantly refused and told her, “As for me, I shall maintain the oath of faithfulness, that I have sworn before God and if pleases the Lord to punish me and the country, then we must submit to it.”3 Seven years after the birth of her first son, Louise Henriette gave birth to a second son named Charles Emil. True to her word, Louise Henriette laid the foundations for the very first orphanage in Germany. Four more children would follow over the years, of which two survived to adulthood. Twins Amalia and Henry died in infancy.

Amalia and Henry’s tombs in the Berliner Dom – Photo by Moniek Bloks

Amalia and Henry’s tombs in the Berliner Dom – Photo by Moniek BloksLouise Henriette and her husband spent a lot of time away from Berlin – and their children – as the war continued to rage around them. She often accompanied him on his campaigns as he valued her advice, but it was difficult for her to leave her young children behind.

She was still only 39 years old when she fell ill shortly after attending the wedding of her youngest sister Maria to Louis Henry, Count Palatine of Simmern-Kaiserslautern in Cleves. She did not feel well enough to travel back to Berlin, and her doctors advised her to spend the season with her mother in The Hague. She remained there for six months before deciding that she needed to return to Berlin. She was accompanied by her sister Henriette Catherine, Princess of Anhalt-Dessau, who would care for her until the end. However, it soon became apparent that she would not make it back to Berlin and her husband hurriedly travelled to see her in Halberstadt. He arranged for another carriage to gently carry her back to Berlin, where she was able to see her children for the last time. She reportedly said on her deathbed, “The Lord treated me like Elijah, to whom he passed a storm, an earthquake and a fire. I hope and trust that it will now come to the soft breeze to announce his proximity.”4 She also wrote, “I have no reason to desire death. I love the Elector, my lord, with all my heart, and so also my dear children, but I would like to be obedient to God.”5

On 18 June 1667, Louise Henriette died in the arms of her husband. She was buried in the Berliner Dom, where her sarcophagus can still be seen.

Louise Henriette’s tomb – Photo by Moniek Bloks

Louise Henriette’s tomb – Photo by Moniek BloksThe post Louise Henriette of Nassau – A sold Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 23, 2020

Book News November 2020

The Lives of Saint Constantina: Introduction, Translations, and Commentaries (Oxford Early Christian Texts)

Hardcover – 4 November 2020 (UK) & 4 January 2021 (US)

Constantina, daughter of the fourth-century emperor Constantine who so famously converted to Christianity, deserves a place of her own in the history of Christianity. As both poet and church-builder, she was an early patron of the Roman cult of the virgin martyr Agnes and was buried ad sanctam in a sumptuously mosaicked mausoleum that still stands. What has been very nearly forgotten is that the twice-married Constantina also came to be viewed as a virgin saint in her own right, said to have been converted and healed of leprosy by Saint Agnes. This volume publishes for the first time critical editions and English translations of three Latin hagiographies dedicated to the empress, offering an introduction and commentaries to contextualize these virtually unknown works.

The Trouble with Women in Power: Leaders Who Dared to Change the World

Hardcover – 26 November 2020 (UK) & 16 February 2021 (US)

From Cleopatra to Margaret Thatcher, and from Christine Lagarde to Joan of Arc, this book focuses on powerful women across the centuries and geographical zones.

At the head of military operations, at the origin of revolutionary laws, dictatorial rulers or emblems of an entire people, these strong-willed women continue to fascinate and inspire. The text―richly illustrated by portraits, photographs, and mythical scenes―also addresses the question of their representations and their attributes of power.

In the history of world rulers, only a relatively small number of women have gained and retained places of power. In order to overcome misogyny, archaic laws governing inheritance, and the constraints of religious fervor, the women featured here incarnate exceptional determination and strength of character. Their stories―often riveting tales of courage in the face of injustice―offer fascinating and rich inspiration.

Catherine the Great: A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works (Significant Figures in World History)

Hardcover – 15 November 2020 (UK) & 15 September 2020 (US)

Catherine the Great: A Reference Guide to Her Life and Works covers all aspects of her life and work. Empress Catherine the Great was one of the most famous and amazing women in world history. ·Includes a detailed chronology of Catherine’s life, family, and work. ·The A to Z section includes the major events, places, and people in Catherine’s life. ·The bibliography includes a list of publications concerning her life and work. ·The index thoroughly cross-references the chronological and encyclopedic entries.

Queens of the Crusades: Eleanor of Aquitaine and her Successors (England’s Medieval Queens)

Hardcover – 5 November 2020 (US & UK)

Alison Weir’s ground-breaking history of the queens of medieval England now moves into a period of even higher drama, from 1154 to 1291: years of chivalry, dynastic ambition, conflict with the church, baronial wars, and the all-pervading bonds of feudalism. We see events such as the murder of Becket, Magna Carta and the birth of parliaments from a new perspective. Her narrative begins with the formidable Eleanor of Aquitaine, whose marriage to Henry II establishes a dynasty which rules for over three hundred years and creates the most powerful empire in western Christendom – but also sows the seeds for some of the most destructive family conflicts in history and for the collapse, under her son King John, of England’s power in Europe. The lives of Eleanor’s successors were just as remarkable: Berengaria of Navarre, queen of Richard the Lionheart, Isabella of Angoulême, queen of John, and Alienor of Provence, queen of Henry III, and finally Eleanor of Castile, the grasping but beloved wife of Edward I.

Marie Antoinette’s Darkest Days: Prisoner No. 280 in the Conciergerie

Paperback – 21 November 2020 (UK) & 21 September 2020 (US)

This compelling book begins on the 2nd of August 1793, the day Marie Antoinette was torn from her family’s arms and escorted from the Temple to the Conciergerie, a thick-walled fortress turned prison. It was also known as the “waiting room for the guillotine” because prisoners only spent a day or two here before their conviction and subsequent execution. The ex-queen surely knew her days were numbered, but she could never have known that two and a half months would pass before she would finally stand trial and be convicted of the most ungodly charges. Will Bashor traces the final days of the prisoner registered only as Widow Capet, No. 280, a time that was a cruel mixture of grandeur, humiliation, and terror. Marie Antoinette’s reign amidst the splendors of the court of Versailles is a familiar story, but her final imprisonment in a fetid, dank dungeon is a little-known coda to a once-charmed life. Her seventy-six days in this terrifying prison can only be described as the darkest and most horrific of the fallen queen’s life, vividly recaptured in this richly researched history.

Queens: 3,000 Years of the Most Powerful Women in History

Paperback – 5 November 2020 (UK & US)

Queens – over 3,000 years of incredible women who ruled the world!

Celebrating strong, brave women across the centuries and around the world, Queens tells their stories of strength and resilience.

Spanning 3,000 years from Cleopatra to the Viking queens, Queen Nanny of Jamaica to HRH Elizabeth II, discover new stories about fierce female monarchs.

Full to the brim with striking, vibrant illustrations and bursting with facts about the queens’ pets, costume, homes, make-up, jewellery, and much much more.

The Afterlife of Anne Boleyn: Representations of Anne Boleyn in Fiction and on the Screen (Queenship and Power)

Hardcover – 19 November 2020 (US & UK)

This book explores 500 years of poetry, drama, novels, television and films about Anne Boleyn. Hundreds of writers across the centuries have been drawn to reimagine the story of her rise and fall. The Afterlife of Anne Boleyn tells the story of centuries of these shifting and often contradictory ways of understanding the narrative of Henry VIII’s most infamous queen. Since her execution on 19 May 1536, Anne’s life and body has been a site upon which competing religious, political and sexual ideologies have been inscribed; a practice that continues to this day. From the poetry of Thomas Wyatt to the songs of the hit pop musical Six, The Afterlife of Anne Boleyn takes as its central contention the belief that the mythology that surrounds Anne Boleyn is as interesting, revealing, and surprising as the woman herself.

The Daughters of George III: Sisters and Princesses

Hardcover – 30 August 2020 (UK) & 23 November 2020 (US)

In the dying years of the 18th century, the corridors of Windsor echoed to the footsteps of six princesses. They were Charlotte, Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary, Sophia, and Amelia, the daughters of King George III and Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Though more than fifteen years divided the births of the eldest sister from the youngest, these princesses all shared a longing for escape. Faced with their father’s illness and their mother’s dominance, for all but one a life away from the seclusion of the royal household seemed like an unobtainable dream. The six daughters of George III were raised to be young ladies and each in her time was one of the most eligible women in the world. Tutored in the arts of royal womanhood, they were trained from infancy in the skills vial to a regal wife but as the king’s illness ravaged him, husbands and opportunities slipped away. Yet even in isolation, the lives of the princesses were filled with incident. From secret romances to dashing equerries, rumours of pregnancy, clandestine marriage and even a run-in with Napoleon, each princess was the leading lady in her own story, whether tragic or inspirational. In The Royal Nunnery: Daughters of George III, take a wander through the hallways of the royal palaces, where the king’s endless ravings echo deep into the night and his daughters strive to be recognised not just as princesses, but as women too.

Espionage in the Divided Stuart Dynasty: 1685-1715

Hardcover – 23 November 2020 (US) & 14 September 2020 (UK)

King James II was the Catholic king of a Protestant nation, but he had inherited a secure crown and was able to put down the rebellion by his nephew the Duke of Monmouth. In just over three years James had been deserted by those he loved and trusted and had to flee to France in exile. His throne was seized by his son-in-law and daughter, and when they died, his younger daughter succeeded. For James it was a personal tragedy of King Lear proportions; for most of his subjects it was a Glorious Revolution that saved his kingdoms from Popery.Over the next hundred years James or his descendants would attempt to win back the crown with French support and conspiring with British Jacobites and Tories. In Espionage in the Divided Stuart Dynasty, Julian Whitehead charts the inner workings of government intelligence during this unstable period, where it was by no means a forgone conclusion that James or his heirs would never regain the throne. It throws light on the murky world of spies and double agents at a time of intensive intrigue and betrayal, with many politicians and peers trying to keep a foot in both camps. It was especially important in such circumstances for a monarch to receive good intelligence about the many intrigues, but could those providing the intelligence be trusted?

Empress Alexandra: The Special Relationship Between Russia’s Last Tsarina and Queen Victoria

Hardcover – 23 November 2020 (US) & 14 September 2020 (UK)

When Queen Victoria’s second daughter Princess Alice married the Prince Louis of Hesse and Rhine in 1862 even her own mother described the ceremony as ‘more of a funeral than a wedding’ thanks to the fact that it took place shortly after the death of Alice’s beloved father Prince Albert. Sadly, the young princess’ misfortunes didn’t end there and when she also died prematurely, her four motherless daughters were taken under the wing of their formidable grandmother, Victoria. Alix, the youngest of Alice’s daughters and allegedly one of the most beautiful princesses in Europe, was a special favorite of the elderly queen, who hoped that she would marry her cousin Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and one day reign beside him as Queen. However, the spirited and stubborn Alix had other ideas…

Joan, Lady of Wales: Power and Politics of King John’s Daughter

Hardcover – 23 November 2020 (US) & 14 September 2020 (UK)

From the time her hand was promised in marriage as the result of the first Welsh-English alliance in 1201 to the end of her life, Joan’s place in the political wranglings between England and the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd was a fundamental one. As the first woman to be designated Lady of Wales, her role as one a political diplomat in early thirteenth-century Anglo-Welsh relations was instrumental. This first-ever account of Siwan, as she was known to the Welsh, interweaves the details of her life and relationships with a gendered re-assessment of Anglo-Welsh politics by highlighting her involvement in affairs, discussing events in which she may well have been involved but have gone unrecorded and her overall deployment of royal female agency.

Sabina Augusta: An Imperial Journey

Paperback – 1 November 2020 (US) & 3 December 2020 (UK)

Sabina Augusta (ca. 85-ca. 137), wife of the emperor Hadrian (reigned 117-38), accumulated more public honors in Rome and the provinces than any imperial woman had enjoyed since the first empress, Augustus’ wife Livia. Indeed, Sabina is the first woman whose image features on a regular and continuous series of coins minted at Rome. She was the most travelled and visible empress to date. Hadrian also deified his wife upon her death.

Children Of The Empire: The Extraordinary Lives of Queen Victoria’s Children and Grandchildren

Paperback – 28 November 2020 (UK) & Unknown (US)

Some lost their thrones. Others supported the Nazis. Several suffered from haemophilia. One had to get a job, and another was executed! Written entirely in the first person and fully based on accurate historical accounts, Michael Farah imagines how this royal family would have described the events of their extraordinary existence, scandals, loves, triumphs and tragedies. In Children of The Empire, forty-seven children and grandchildren of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert individually tell the stories of their lives, from their early childhood to the very end. Complete with individual portraits and family trees, this is an accessible and unique look at the extended royal family that has stretched across Europe, some of them becoming Kings and Queens.

Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’

Paperback – 15 November 2020 (UK) & 15 February 2021 (US)

Anna was the ‘last woman standing’ of Henry VIII’s wives ‒ and the only one buried in Westminster Abbey. How did she manage it? Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’ looks at Anna from a new perspective, as a woman from the Holy Roman Empire and not as a woman living almost by accident in England. Starting with what Anna’s life as a child and young woman was like, the author describes the climate of the Cleves court, and the achievements of Anna’s siblings. It looks at the political issues on the Continent that transformed Anna’s native land of Cleves ‒ notably the court of Anna’s brother-in-law, and its influence on Lutheranism ‒ and Anna’s blighted marriage. Finally, Heather Darsie explores ways in which Anna influenced her step-daughters Elizabeth and Mary, and the evidence of their good relationships with her. Was the Duchess Anna in fact a political refugee, supported by Henry VIII? Was she a role model for Elizabeth I? Why was the marriage doomed from the outset? By returning to the primary sources and visiting archives and museums all over Europe (the author is fluent in German, and proficient in French and Spanish) a very different figure emerges to the ‘Flanders Mare’.

Young Elizabeth: One Extraordinary African Summer in the Life of the Princess

Paperback – 5 November 2020 (UK) & 4 May 2021 (US)

The year of the royal tour of southern Africa, 1947, marked both the high-water mark of the British Empire and the very moment at which it began to unravel. Graham Viney has written an intimate, revealing portrait of the young princess on tour with her parents and sister, Princess Margaret, hard at work in the national interest, and succeeding triumphantly against all odds. In the words of Rian Malan, South African author of My Traitor’s Heart, it is ‘a story about a country teetering on the brink of convulsive change and yet almost united, at least for a moment, by love for a king and queen who weren’t really ours.’

The post Book News November 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 21, 2020

Louise of Prussia – A Prussian through and through (Part two)

In 1879, Louise’s 17-year-old daughter Victoria was introduced to Gustav, the future King of Sweden, and their betrothal was announced later that year. On 20 September 1881, which was also Louise and Frederick’s 25th wedding anniversary, their daughter married Crown Prince Gustav. Although Victoria was well-received in Sweden as a descendant of the former Swedish Vasa monarchy, it was not to be a happy marriage. Thoughts soon turned to the marriage of her eldest son, but a possible match with Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine fell through, and she went on to marry Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia. On 20 September 1885, he married Princess Hilda of Nassau, the daughter of the future Grand Duke of Luxembourg.

In 1887, Louise travelled to Berlin to help organise the festivities for her father’s 90th birthday, and she stayed around after his birthday as her brother was beginning to become quite ill himself. She began to act as a sort of press secretary – sometimes without consulting her father or brother – to the anger of her sister-in-law Victoria who angrily wrote to her mother, “Dear Louise of Baden questions & talks me to death till I nearly turn rude!”1 The year 1888 would not only become the year of the three Emperors, but it would also see Louise suffer the loss of her youngest son Louis at the age of 23. The official cause of death was an inflammation of the lungs, though it was rumoured that he had been killed in a duel.

(public domain)

(public domain)Already in mourning for her son, she sat by her dying father’s bedside and on the evening of 8 March she told him, “You have told us so much that was interesting, perhaps you would like to rest a little now.”2 He died the following day, just two weeks after his young grandson. Louise’s brother now became Emperor Frederick III, but he too was dying – of cancer of the larynx. He could not speak anymore, and his reign would last just 99 days. He died on 15 June 1888. Louise attended the funeral with her mother, who was by now confined to a wheelchair. Her nephew had now become Emperor Wilhelm II. Louise and her ageing mother became closer in her final years, and Louise was by her bedside when her mother died on 7 January 1890. Her sister-in-law wrote to Queen Victoria that Louise was “sorely stricken & feels her mother’s death very much.”3

Louise and her husband remained healthy in their old age for quite a while, and her husband celebrated his Golden Jubilee in 1906 with a grand celebration. King Edward VII sent his brother the Duke of Connaught to invest him with the Order of the Garter. The following year, just days before his 81st birthday, Frederick became ill. Louise and her daughter Victoria travelled to Mainau to nurse him back to health but to no avail. He died on 28 September 1907. His funeral took place on 6 October in Karlsruhe. Their son was now Frederick II, Grand Duke of Baden but his marriage to Princess Hilda had remained childless. His heir was his first cousin, Prince Maximilian of Baden.

Just two months later, Louise saw her daughter become Queen consort of Sweden with the death of King Oscar II of Sweden and her son-in-law’s accession as King of Sweden. Victoria had given her husband three sons, but she spent most of the year away from the Swedish court.

Louise would live to see the world plunge itself into the Great War, but although she was too old to take up nursing duties, she sent financial support. She and her daughter were once almost the victims of a bombing raid, but although the castle was damaged, they were not harmed. At the end of the war, Louise bitterly witnessed the fall of several German monarchies and the return of the German soldiers. Her nephew Emperor Wilhelm II abdicated in November 1918 and went into exile in the Netherlands. Louise’s son abdicated on 22 November 1918, but Louise was allowed to spent her last years in Baden and Mainau.

During her final years, Louise saw the wedding of Hermine Reuss of Greiz to her nephew, the former Emperor Wilhelm II. Louise had taken Hermine under her wing when she had been orphaned at the age of 14 and had always treated her like one of her own children. Even though most of Wilhelm’s family resented the match, Louise showed her support and the two were married in November 1922. Louise became ill in the spring of 1923. She died on 24 April 1923 – having seen the world change shape in the most astonishing ways. She was buried with her husband at Karlsruhe.

The post Louise of Prussia – A Prussian through and through (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 20, 2020

Louise of Prussia – A Prussian through and through (Part one)

Princess Louise of Prussia was born on 3 December 1838 as the second child of the future Wilhelm I, German Emperor and Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. She would be the only sibling of the future Emperor Frederick III, and he was seven years her senior. Her first name was chosen in honour of her grandmother Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Her parents had a marriage of convenience, and her mother promptly declared that there would be no more children.

On 7 June 1840, Louise’s grandfather died, and her childless uncle succeeded as King Frederick William IV of Prussia. Louise’s father now became the heir to the throne. Her father was relatively cold towards his son and heir, while Louise appeared to have stolen his heart. He could often be found sitting on the floor, playing with her. Louise herself was also not particularly close to her elder brother in their youth, probably due to the large age difference but they would become closer as they grew older. Her mother made sure that Louise received an excellent education, though she was known to censor the more inconvenient truths from Louise.

At the age of 12, Louise accompanied her parents and brother on a trip to London where they visited the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace and were shown around by Victoria, Princess Royal, who was two years younger than Louise and who would in due time become her sister-in-law. Queen Victoria later wrote, “Vicky has formed an amazing friendship for that charming Child Vivi (Louise) & also for the young Prince; might this, one day, lead to a union!”1 Louise also became fond of the eight-year-old Princess Alice.

At the age of 15, Louise was betrothed to Frederick, then Regent of Baden. He was regent for his brother, Louis II, Grand Duke of Baden, who was mentally ill, and he was 12 years older than his young bride. They were married on 20 September 1856 at the chapel of the New Palace in Potsdam with Louise’s aunt Elisabeth placing the wedding crown on the bride’s head. He had officially taken over his brother’s title of Grand Duke earlier in the year, despite him still being alive, and so upon marriage, Louise immediately became the new Grand Duchess of Baden. The newlyweds divided their time between a home in Karlsruhe and Mainau Castle on Lake Constance – which Louise much preferred.

Just a few weeks after their wedding, Louise realised she was pregnant. On 9 July 1857, not even a year after the wedding, Louise gave birth to a son – the future Frederick II, Grand Duke of Baden. The following year, Louise’s brother married Queen Victoria’s daughter the Princess Royal, but Louise and her husband were not present as the former Grand Duke Louis was seriously ill. He died just three days before the wedding at the age of 33. They were instead represented by Frederick’s younger brother William.

(public domain)

(public domain)Louise and Victoria developed a bit of rivalry, especially after Victoria’s eldest son was born with a damaged left arm. According to Victoria, Louise apparently boasted that “hers was bigger the day he was born than mine is now after eight weeks wh. I take very ill & wh. surely is hardly possible.”2 However, the sisters-in-law had a common enemy, Louise and Frederick’s mother Augusta, who was equally cold to them and their husbands.

On 2 January 1861, King Frederick William IV – Louise’s uncle – died, making her father and mother the new King and Queen and her brother Frederick with Victoria the new Crown Prince and Crown Princess. The following year, Louise gave birth to a daughter named Victoria – the future Queen of Sweden. The infant Victoria had suffered a broken right arm during the delivery, but it healed just fine. On 12 June 1865, Louise gave birth to her third and final child – a son named Louis.

With a new Imperial Constitution in 1871, Baden became an integral part of the new German Empire, under the leadership of Louise’s father, who became Wilhelm I, German Emperor. Otto von Bismarck, the chancellor of the German Empire, distrusted Louise because of the Catholic influence coming from Baden. This only deepened when she interceded with her father on behalf of the oppressed Catholics of Alsace. Louise spent plenty of time at the court in Berlin and, although she had once mocked her young nephew, she knew he was the future Emperor and became an indulgent aunt to him. He would later recall her fondly. He also got along with her cousin Frederick, Louise’s eldest son, who was two years older than him.

Part two coming soon.

The post Louise of Prussia – A Prussian through and through (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 19, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – A fifth miscarriage

With Wilhelmina’s marriage to Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin on 7 February 1901, she and her mother both fervently prayed for healthy children to continue their line. Tragically, Wilhelmina would go on to suffer five miscarriages and only one healthy child was born to Wilhelmina and Henry.

Though the relief at the birth of Princess Juliana in 1909 was great, she would remain an only child to her regret but also to the regret of Wilhelmina and Henry. The fifth and final miscarriage happened at Noordeinde Palace on 20 October 1912. Kouwer, the gynaecologist who had stood by Wilhelmina through the many miscarriages, was summoned but there was nothing more he could do. Newspapers reported a “minor indisposition of the Queen” that “foiled the hope that had been held briefly.”1

Wilhelmina herself found solace in her faith as she always did. Without specifically referencing her miscarriages, she wrote in her memoirs, “My faith and love for Christ were subjected to many tests in the course of my life. The first test was the decisive one. In difficult circumstances, I was confronted with an inescapable choice: to remain true to Him at a time when it demanded a sacrifice, or to give in to temptation, even for only a moment. I recognised clearly that it would be shameful to follow Him in prosperity and to deny Him in adversity; to forget one’s vow when it demanded self-abnegation, to argue; that is is not how I meant my promise to follow Him. To forsake this loyalty, the highest and best thing in us – I could not even bear to think of what one would be after such an irreparable rupture. After a struggle, I made the sacrifice and chose to do Christ’s will.”2

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – A fifth miscarriage appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 18, 2020

Amrapali – A royal courtesan

This article was written by Shivangi Kaushik.

The infant Amrapali was reportedly found at the trunk of a mango tree in the city of Vaishali in around 600-500BCE in ancient India. Her name is made up of two Sanskrit words ‘Amra’ which means mango and ‘pallav’ meaning young leaves. She was raised by a couple from the city.

Amrapali grew up to be an extraordinarily beautiful and charming woman. She was trained in many classical dance forms and, she once participated in a dance competition. She won the competition and caught the eye of the nobles and princes. As was the custom, the winner of the competition was declared ‘Nagar Vadhu’ which means city courtesan. They all vied for her love and attention. To avoid conflict among them, she was declared a Nagar Vadhu. It was customary for a ‘Nagar Vadhu’ to dedicate herself to the pleasure of nobles and princes rather than be devoted to only one, but Amrapali had a right to choose her lover. She was also declared a court dancer.

Her beauty and talent attracted people from far and wide. Over time, she became richer than many nobles and princes of Vaishali. By then, Bimbisar, the King of Magadh, had heard about her. Magadh was an enemy state of Vaishali. He entered Vaishali in the disguise of an ordinary soldier, to spy on the democratic practices of Vaishali. He wanted to see how the government of Vaishali elected one Prince from among the many princes of various states. A chance meeting with Amrapali, during which Bimbisar saved her life, brought him in close proximity to her.

Bimbisar was a gifted musician himself. He spent many days with her in her palace. Amrapali found herself falling in love with him, and he reciprocated her feelings before revealing his true identity to her. She was shocked and anguished to find that she had fallen in love with the enemy, and she asked him to leave. However, Bimbisar managed to convince her to marry him. After a few days of their secret marriage, they were found out, and his true identity was revealed to the entire city. People thronged to Amrapali’s palace and blamed her for hiding an enemy.

Amrapali was then taken a prisoner on charges of treason. Bimbisar managed to escape from the palace with the help of his soldiers. Amrapali was sentenced to life in prison. At that point in time, she was also pregnant with King Bimbisar’s child. Bimbisar learnt about the sentence given to his wife. He ordered an immediate attack on Vaishali in order to save his wife and his unborn child. Thousands of soldiers were killed during this attack, and there was vast destruction in Vaishali. Amrapali was heartbroken that her love led to the destruction of her beloved city and its people.

Bimbisar defeated Vaishali and managed to free Amrapali. When she was released from prison, she saw the thousands of bodies of the dead soldiers and women crying over dead bodies of their husbands, fathers and brother. She became dejected and restless, and she refused to go with Bimbisar.

A few days later, she learnt of Gautam Buddha (also known as The Buddha – founder of the world religion of Buddhism) visiting Vaishali. She invited him to her home and expressed her desire to take refuge with him. She donated her palace and the mango grove around it to ‘sangha’. She eventually became a ‘bhikshuni’ (female monk). Her son reportedly also became a monk.

The post Amrapali – A royal courtesan appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 17, 2020

Blog Tour: Medical Downfall of the Tudors

Join us today for the blog tour of Sylvia Barbara Soberton’s new book Medical Downfall of the Tudors with an article called: When did Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon stop sleeping together?

When did Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon stop sleeping together?

Open any nonfiction book about the Tudors, and you will learn that that by 1524 Henry VIII had stopped sleeping with Katharine of Aragon.1 This, however, is one of the most enduring myths about Henry’s marriage to his first wife. In 1527, Henry VIII initiated a divorce case known in its early stages as the Great Matter. The King’s infatuation with Katharine’s maid of honour, Anne Boleyn, was cited among many courtiers as the real reason behind the royal divorce. However, Henry maintained that the fact that Katharine was previously married to his elder brother was the reason for his decision.

Katharine and menopause

Popular, as well as academic narratives, will tell you that Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon stopped having sexual relations in 1524 and that by 1527 Katharine was already menopausal. The available evidence does not suggest that this is the case, however. While it is true that Katharine was forty-two when Henry decided to terminate their marriage, there is no evidence that she was going through menopause at the time or even before the year 1527. However, the Venetian ambassador probably wasn’t alone in thinking that Henry sought a divorce because Katharine was his late brother’s widow and because she was “of such an age” that he could no longer hope for offspring from her.2 Henry never referred to Katharine’s inability to bear children in general. Still, he always maintained that she was unable to bear him sons because she was his brother’s widow, and therefore God punished them with the lack of male heirs. His main reason to repudiate Katharine and marry Anne Boleyn was his desire to produce male children. Katharine was unable to produce sons, not because she was already menopausal, but because their union was cursed and offensive to God, in Henry’s view at least. This was Henry’s line of defence, and this he would strenuously maintain until the end of the proceedings.

Fertility was certainly not Katharine of Aragon’s problem. She conceived on a regular basis, although her pregnancies resulted either in stillbirths or the early death of infants (another persisting myth is that she endured numerous miscarriages). Only Princess Mary survived the perils of early childhood and lived to reach adulthood. Katharine’s last recorded pregnancy occurred in 1518, when she was thirty-three, about the same age Anne Boleyn was when she gave birth to her first child in 1533. If Henry feared Katharine was unable to bear him any more children, then why didn’t he say anything? The answer seems clear: Katharine was still deemed able to conceive.

Sleeping with the King

During the Blackfriars trial of the royal marriage in 1529, Thomas Boleyn said that it was common knowledge that “the King and Queen cohabited till about two years ago when he heard that the King was advised by his confessor to abstain from intercourse with the Queen, so as not to offend his conscience”.3 As the father of Henry VIII’s wife-to-be, Thomas Boleyn was certainly well informed about the goings-on in the royal bedchamber, and he said that Henry and Katharine stopped sleeping together in 1527. A letter from Cardinal Wolsey to the King’s representative in Rome said that Henry shunned Katharine’s bed because of “certain diseases in the Queen defying all remedy”.4 The implication was clear: Katharine’s unspeakable “diseases” were of an intimate nature. But if Katharine was indeed diseased, why didn’t Henry react earlier? Perhaps because, as Katharine of Aragon’s modern biographer asserts, “the Queen was not diseased”, and Wolsey was desperate to obtain the annulment.5

A year later Henry resumed visits to Katharine’s bedchamber, and according to the Imperial ambassador, “they dine and sleep together”. This, the ambassador thought, was because Henry wanted to avoid accusations of “acting in defiance of the Queen’s conjugal rights”, as the lack of conjugal relations in a marriage was strongly condemned by religious authorities.6 There is no certainty that they had resumed a sexual relationship, but it is contradictory to earlier reports about Katharine’s mysterious diseases, which allegedly led Henry to shun her bed. Katharine’s staunch supporter, Eustace Chapuys, believed in 1535 that she was still fertile, and he based that observation on interviews with her physicians.7 If Katharine was menopausal at the beginning of the divorce case in 1527, Henry VIII could well have used that as proof that she was physically unable to bear him more children, as the stoppage of menstrual courses was understood as the end of a woman’s childbearing years. Yet he never did that.

Medical Downfall of the Tudors by Sylvia Barbara Soberton is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Blog Tour: Medical Downfall of the Tudors appeared first on History of Royal Women.

October 15, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The announcement of the engagement between Wilhelmina and Henry

With their engagement having just taken place four days previously, Queen Wilhelmina and Henry announced their engagement on 16 October 1900 with a proclamation.

“To my people!

It is a need to me, to the Dutch people, of whose lively interest in the happiness of me and my House I am so deeply convinced, to inform you personally of my engagement with His Highness, Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

May this event, with God’s blessing, benefit the wellbeing of our country and its possessions and colonies in East and West. [..]

Done at The Loo Palace, on this day 16 October 1900 – Wilhelmina.”1

A delighted Wilhelmina wrote to her former governess Miss Winter, “Oh darling, you cannot even faintly imagine how frantically happy I am and how much joy, and sunshine has come upon my path.”2

After heavy negotiations concerning his income, his status and titles, the two were married on 7 February 1901. Henry became known as Prince Hendrik in the Netherlands, and he became Prince Consort.

He was also awarded the style of “Royal Highness.” Henry’s initial reception in the Netherlands had been somewhat lukewarm, but his popularity grew over time. One of the defining moments for this came in 1907 when the Berlin ferry – which served the Harwich/Hook of Holland route – broke in two and sank. Henry arrived the following day to help with the recovery of the bodies, but they also found a handful of survivors on the floating stern. There had been around 144 passengers on board. Once the survivors had been brought to safety, Henry helped to care for the victims and even poured them coffee or cognac. His easy-going nature also made him popular amongst the palace servants.

Though initially a happy match, Wilhelmina and Henry would grow apart over the years. She would suffer several miscarriages and a stillbirth before finally giving birth to a healthy baby girl named Juliana in 1909. She was his pride and joy until the day he died, and they always remained on good terms, despite the wavering relationship between Henry and Wilhelmina.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The announcement of the engagement between Wilhelmina and Henry appeared first on History of Royal Women.