Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 162

November 21, 2020

Queen Mary II – This dear country (Part four)

Mary passed the hours in prayer, both in public and in private. She only relaxed a little when she heard of William’s landing at Torbay, but the days passed slowly for her. Then the news came of William’s success and how James had sent his wife and child to safety before William had allowed him to escape as well. Mary learned of this at the end of December, and William asked her to prepare for her journey to England. Once Mary had tearfully said goodbye to England, now she would tearfully say goodbye to the Netherlands. She wrote, “I could not think without chagrin of leaving this dear country, where I had had such happiness, both spiritual and temporal.”1

In the end, it was agreed that Mary and William would reign jointly, but William (who was technically behind both his wife and his sister-in-law Anne in the line of succession) would also reign for life – meaning he would remain King if Mary predeceased him. He did concede to having any of Anne’s children take precedence over any heirs he might produce with a second wife. Mary was troubled to find herself taking her father’s place, but there was no going back. As she returned to England, she wrote, “It would be hard for me to express the different motions I felt in my heart at the sight of my own native country. I looked behind and saw vast seas between me and Holland that had been my country for more than eleven years. I saw with regret that I had left it and I believed it was for ever; that was a hard thought, and I had need of much more constancy than I can brag of, to bear it with patience.”2

(public domain)

(public domain)William and Anne were waiting for her at Greenwich, and together they travelled to Whitehall. In the Banqueting Hall, the two Houses of Parliament arrived to offer William and Mary the Crown. Mary found no pleasure in being Queen. She wrote, “My heart is not made for a Kingdom, and my inclination leads me to a retired life, so that I have need of the resignation and self denial in the world, to bear with such condition as I am now in. Indeed the Prince’s being made King has lessened the pain, but none of the trouble of what I am like to endure.”3 William was unhappy as well, as his health suffered from life in London. At the end of February 1689, they moved to Hampton Court to prepare for their coronation.

On 11 April 1689, they were crowned together, though by then William had developed such a bad cough that it was feared he would die before then. It was an overall unpleasant day, and Mary later wrote, “The Coronation came on; that was to be all vanity.”4 Mary joined her pregnant sister Anne at Hampton Court and was present at the birth of her son – named William for the King – finally gave the pair some hope that God had approved of their mission. Mary prayed for the sickly boy all the time. Looking back on her first year as Queen, she would write, “It has pleased God to make this a year of trial in every way.”5

The following year, William left for Ireland to fight against Jacobites (those who supported King James II) and left Mary in charge. She was only to deal with matters that needed immediate attention and Mary was all too happy to submit herself. She did not enjoy being the centre of attention, and when William left, she wrote to him nearly every day. Her council of nine men were soon bickering amongst each other, forcing Mary to rely more on her own judgement. She found it difficult and wrote to William, “I ever fear not doing well and trust to what nobody says but you.”6 Over the next few years, William was away for several months of the year, facing Jacobite opposition, leaving Mary in charge but she was most happy living a domestic life. She liked to rise early, went to prayers, walked in the gardens and if she had the time, she would embroider.

In the autumn of 1694, Mary had a cold twice, and after she lost a ruby from a ring William had given her, she saw it as a bad omen. By December, she was rather unwell, but she told no one and went to Kensington Palace where she probably burned letters and her diary from that year. She even wrote out instructions for her funeral. Only after she did this, did Mary tell William of her illness. She assumed that had smallpox and doctors agreed with her diagnosis. William’s mother had died of the same disease in 1660, and he immediately feared the worst. Everyone who had not already had smallpox was sent away, and Mary treated herself with the remedies she usually used for a cold. On 23 December, she developed a rash.

William tried to go on with government, but he was in such a state that he burst out in tears, saying that “from being the happiest, he was now going to be the miserablest creature upon earth.”7 Two days later, the rash subsided, and Mary seemed a little better. Doctors still bled and purged her, and also applied leeches to her neck. William had a bed moved into Mary’s room so he could be closer to her. Then hope began to fade as Mary gradually became more breathless. She was by now spitting blood, and there was also blood in her urine. On 27 December, she received the sacrament as William wept openly. He was led away to the ante-room where he fainted from exhaustion. Her sister Anne – pregnant once more – offered to come at once but she was politely told to stay where she was. Later that day, Mary became unconscious, and she died at a quarter to one in the morning of 28 December. She was still only 32 years old.

Embed from Getty Images

William was devastated by her death and never married again. On 5 March, Mary’s funeral took place at Westminster Abbey, and it was a grand affair, despite her own wishes. She, and William too eventually, was buried in a vault beneath the South Aisle.

The post Queen Mary II – This dear country (Part four) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 20, 2020

Book News December 2020

Hermine: an Empress in Exile: The untold story of the Kaiser’s second wife

Paperback – 1 January 2021 (US) & 11 December 2020 (UK)

Hermine Reuss of Greiz is perhaps better known as the second wife of the Kaiser (Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany) whom she married shortly after the death of his first wife Auguste Viktoria and while he was in exile in the Netherlands. She was by then a widow herself with young children. She was known to be ambitious about wanting to return to power, and her husband insisted on her being called ‘Empress’. To achieve her goal, she turned to the most powerful man in Germany at the time, Adolf Hitler. Unfortunately, her dream was not realised as Hitler refused to restore the monarchy and with the death of Wilhelm in 1941, Hermine was forced to return to her first husband’s lands. She was arrested shortly after the end of the Second World War and would die under mysterious circumstances while under house arrest by the Red Army.

Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia: Brother and Sister of History’s Most Vilified Family

Hardcover – 30 September 2020 (UK) & 31 December 2020 (US)

Myths and rumour have shrouded the Borgia family for centuries – tales of incest, intrigue and murder have been told of them since they themselves walked the hallways of the Apostolic Palace. In particular, vicious rumour and slanderous tales have stuck to the names of two members of the infamous Borgia family – Cesare and Lucrezia, brother and sister of history’s most notorious family. But how much of it is true, and how much of it is simply rumour aimed to blacken the name of the Borgia family? In the first ever biography solely on the Borgia siblings, Samantha Morris tells the true story of these two fascinating individuals from their early lives, through their years living amongst the halls of the Vatican in Rome until their ultimate untimely deaths. Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia begins in the bustling metropolis of Rome with the siblings ultimately being used in the dynastic plans of their father, a man who would become Pope, and takes the reader through the separate, yet fascinatingly intertwined, lives of the notorious siblings. One tale, that of Cesare, ends on the battlefield of Navarre, whilst the other ends in the ducal court of Ferrara. Both Cesare and Lucrezia led lives full of intrigue and danger, lives which would attract the worst sort of rumour begun by their enemies. Drawing on both primary and secondary sources Morris brings the true story of the Borgia siblings, so often made out to be evil incarnate in other forms of media, to audiences both new to the history of the Italian Renaissance and old.

Katherine Parr: Opportunist, Queen, Reformer: A Theological Perspective

Hardcover –15 March 2021 (US) & 15 December 2020 (UK)

Unlike other biographies, which have focused on the court politics of the Tudor era, the romantic desires of Henry VIII that drove his serial marriages, and the military and economic challenges to England at the time, this biography remembers the central influence of religious belief on the king and queen, and explains how Katherine’s devotion to the self-questioning protestant ethos had a directing influence on her actions. In particular, the author identifies her seminal work, “The Lamentation of a Sinner,” as the key to unlocking Katherine’s personality. These were more religious times than secular readers today might at first appreciate, but this book shows it is crucial to our understanding of why the last years of Henry VIII’s reign played out as they did, and how his last queen survived when her predecessors suffered divorce and execution.

The Palace Letters: The Queen, the governor-general, and the plot to dismiss Gough Whitlam

Paperback – 10 December 2020 (UK) & 4 May 2021 (US)

What role did the queen play in the governor-general Sir John Kerr’s plans to dismiss prime minister Gough Whitlam in 1975, which unleashed one of the most divisive episodes in Australia’s political history? And why weren’t we told?

The Borgias: Power and Fortune

Paperback – 8 December 2020 (US & UK)

The glorious and infamous history of the Borgia family—a world of saints, corrupt popes, and depraved princes and poisoners—set against the golden age of the Italian Renaissance.

The Borgia family have become a byword for evil. Corruption, incest, ruthless megalomania, avarice and vicious cruelty—all have been associated with their name. And yet, paradoxically, this family lived when the Renaissance was coming into its full flowering in Italy. Examples of infamy flourished alongside some of the finest art produced in western history.

Sabina Augusta: An Imperial Journey

Paperback – 1 November 2020 (US) & 3 December 2020 (UK)

Sabina Augusta (ca. 85-ca. 137), wife of the emperor Hadrian (reigned 117-38), accumulated more public honors in Rome and the provinces than any imperial woman had enjoyed since the first empress, Augustus’ wife Livia. Indeed, Sabina is the first woman whose image features on a regular and continuous series of coins minted at Rome. She was the most travelled and visible empress to date. Hadrian also deified his wife upon her death.

Royal Seals: Images of Power and Majesty (Images of The National Archives)

Hardcover – 30 December 2020 (US) & 2 November 2020 (UK)

Royal Seals is an introduction to the seals of the kings and queens of England, Scotland and latterly the United Kingdom, as well as the Church and nobility.

Ranging from Medieval times to modern day, it uses images of impressive wax seals held at The National Archives to show the historical importance of these beautiful works of art.

Included are features on the great seals of famous monarchs like Richard III, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and twentieth-century monarchs, as well as insights on the role of seals in treaties and foreign policy.

With ecclesiastical seals and those of the nobility and lower orders included, this is a comprehensive and lavishly illustrated guide.

The post Book News December 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 19, 2020

Queen Mary II – A good wife (Part three)

In August 1682, Mary received the news of the birth of another half-sister, but the little girl lived for just two months. The rest of the year of 1682 was spent rather domestically for Mary; she bought a new cockatoo and items for her household. For William, it was a politically frustrating year. In May 1683, her old friend Frances gave birth to twin boys – just as Mary had wished her in her letters. Tragically, one of them did not survive, and Mary wrote to her, “When I wish you joy of your son you may believe I do it from the bottom of my heart, and that you may have as many more as you can wish, to repair the loss of the dead one.”1 Just a little while later, Frances lost the second twin as well. When Frances suffered a miscarriage a little later on, Mary – knowing the pain all too well – wrote, “One can hardly go about to comfort you, and indeed upon such occasion ’tis only from God it can come whom I beseech to grant you may bear it like a Christian.”2

When her sister Anne married Prince George of Denmark in 1683, Mary was glad to learn that Anne found him congenial. She wrote to Frances, “You may believe it was no small joy to me to hear she liked him and I hope she will do so every day more and more for else I am sure she can’t love him and without that ’tis impossible to be happy which I wish her with all my heart as you may easily imagine knowing how much I love her.”3 Though perhaps happy in her relationship, Anne’s marriage meant the beginning of many years of miscarriages, stillbirths and short-lived children.

In February 1685, Mary’s uncle King Charles II died at the age of 54 without legitimate issue. This meant that her father now became King James II of England, Scotland and Ireland and he would be the last Catholic monarch. Then her protestant – but illegitimate – cousin The Duke of Monmouth launched a rebellion and William duly sent a few regiments to help defend England and his father-in-law. In the end, the rebellion failed, and the Duke of Monmouth was executed in July. With her father now King and still no surviving half-siblings, Mary was now the heir to the throne.

During this time, Mary laid the foundation for the Loo Palace in Apeldoorn. Planning the new palace took Mary’s mind off the family troubles as every letter her father sent her upset her very much. Mary appeared to be unaware of her husband’s attachment to Elizabeth Villiers until her father told her about it. Rumour had it that Mary caught him as he was leaving Elizabeth’s rooms, but this could very well be untrue. In any case, Mary eventually told her husband that “she had kept her sorrow locked in her heart.”4 If he continued to see Elizabeth, he was more discrete about it, and Mary learned to live with it.

During the year 1686, Mary was again in quite ill-health. She had trouble with her eyes and had put on weight – though not because of a pregnancy as many had hoped. She wrote to Lady Mary Forester – who had just had a child – that she was happy for her and “I am not changed in my humour though I am in my shape, but that not by so good a reason as you had when I saw you last, but mere fat. I like this subject so little I shall say no more upon it.”5 Just a short while later, Mary fell from her horse and had to be treated by her doctor.

Meanwhile, in England, things were slowly getting worse. In 1688, Mary’s stepmother, at last, gave birth to a son who lived – James Francis Edward Stuart. With a male and moreover Catholic heir to displace Mary as heiress to the throne, protestant politicians had had enough. At the end of June, one Admiral Herbert came to the Netherlands carrying an important document. The document was signed by the so-called immortal seven and thanked William for being ready to give his assistance and “we have great reason to believe we shall be every day in a worse condition than we are, and less able to defend ourselves, and therefore we do earnestly wish we might be so happy as to find a remedy before it be too late for us to contribute to our own deliverance.”6 William was being invited to invade.

Mary received a letter from her stepmother who wrote, “The first time I have taken a pen in my hand since I was brought to bed, is this, to write to my dear Lemon.”7 She wrote about miscalculating her dates, and that she almost believed she had come before her time if the child had not been so big and strong. Mary was in a dilemma but in the end, agreed that prayers for the boy should be discontinued, if only for the strange rumours surrounding his birth. William convinced Mary that there was no other way of saving Church and State but to dethrone her father. And while William prepared ships and troops, all Mary could do was pray and brood.

Her stepmother learned of the rumours of an invasion and wrote to Mary, “I don’t believe you could have such a thought against the worst of fathers, much less against the best, that has always been kind to you and loved you better than all the rest of his children.”8 Mary arrived in The Hague in October to find a letter from her father. He wrote, “I easily believe you may be embarrassed how to write to me now that the unjust design of the Prince of Orange’s invading me is so public. And though I know you are a good wife and ought to be so, yet for the same reason, I must believe you will be still as good a daughter to a father that has always loved you so tenderly, and that has never done the least thing to make you doubt it. I shall say no more, and believe you very uneasy all this time, for the concern you must have for a husband and a father. You shall still find me kind to you if you desire it.”9

As William’s forces began to build up, James started to panic. On 26 October, William told the Assembly, “What God intends for me I do not know, but if I should fail, take care of my adored wife who has always loved this country as if it were her own,” leaving many of the deputies in tears.10 He told Mary that if the worst were to happen, she should marry again. She assured him that she never loved anyone but him and would never love anyone else.

As Mary waited for news of William, she became ill with kidney pains and found it hard to sleep at night. She was depressed and had to be bled. William had been forced to wait out the weather, and he invited Mary – if only for one last glimpse of her. The second goodbye was even more heartbreaking than the first, and the following day Mary watched as the fleet set sail.

Part four coming soon.

The post Queen Mary II – A good wife (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 17, 2020

Queen Mary II – Princess Lemon (Part two)

Mary spent her first days in her new country recovering from the journey. She also finally got to know the man she had so tearfully married. When he began to trust her, Mary could finally see the man he really was – funny, emotional and concerned. William soon took her to The Hague to show her the stately building where he had been born and had spent much of his childhood.

In early January, Mary performed her first solo duty – receiving the important ladies of The Hague in audience – but a question of etiquette left some ladies in tears. It was not a good start. William’s tightknit group of friends resented Mary’s presence at first, but they soon grow to like her as they got to know her better. Mary began to feel more at home, and she easily fell into a new routine. Her newfound happiness was complete when she learned that she was pregnant in early 1678. However, she would soon need to say goodbye to her new husband as he headed off to war with France. Mary wrote, “I suppose you know the prince is gone to the army, but I am sure you can guess at the trouble I am in, I am sure I could never have thought it half so much. I thought coming out of my own country, parting with my friends and relations the greatest that ever could, as long as they lived, happen to me, but I am mistaken that now till this time I never knew sorrow, for what can be more cruel in the world than parting with what one loves?”1

Mary was continually worried for William’s safety, writing, “I reckon him now never in safety, ever in danger, oh miserable life that I lead now.”2 At the end of March, she was finally able to see him in Antwerp and spent two weeks there. She returned to The Hague only to be summoned south to Breda again a few weeks later. She was by then around three months pregnant, and she had only just arrived there when she suffered a miscarriage. Her being in Breda was particularly unfortunate as the regular court physicians could not attend on her. Both William and Mary were very disappointed, and Mary’s father wrote to her, asking her to be more careful. William soon sent her back home, further from the front, and it appeared that she was recovering well from her miscarriage.

Mary’s first summer in the Netherlands was spent with her ladies travelling around the country. She loved to travel on the canals in beautiful boats with canopies. She spent her time watching the landscape slide by, playing cards, doing embroidery or talking with her ladies. She learned to speak and understand Dutch reasonably well. The happy days of summer were interrupted by yet more trouble with France and Mary was left alone again. She was by then no more than six or seven weeks into what she believed to be her second pregnancy. By the end of August, most of the court seemed to believe that Mary was pregnant again. In early September, Mary was unwell with a fever, and she initially did not join William in The Hague. She was treated with “asses’ milk and physic.”3 She felt very low and her stepmother Mary of Modena and her sister Anne came over to see her. They stayed at Noordeinde Palace, and Mary was carried in her chair to them. During this time, Mary received a new nickname from her young stepmother and sister, namely “Lemon” as her husband was the Prince of “Orange.” They returned home on 18 November.

Mary of Modena returned to the Netherlands in early March 1679 with her husband – to everyone’s great surprise. They stayed in The Hague for a few days before travelling to Brussels. By then, Mary had gone well over the nine-month mark for a pregnancy, and there was still no sign of a child. Did she suffer a phantom pregnancy? Was she perhaps left permanently infertile by the awful miscarriage at Breda? Mary herself was devastated, and by April she was struck down by a high fever and an agonising pain in her hip. She was bled several times and reportedly felt better. By the summer, she was well enough to travel to Dieren, where William loved to hunt and had a house built. At the end of the summer, she went to take the waters at Spa. In October, Mary saw her father, stepmother and little half-sister Isabella for the last time. Young Isabella would die in 1681, but her father and stepmother would become her enemies in just a few years.

In March 1680, Mary was again seriously ill with William writing to his father-in-law that she was in great pain. Rumours of a miscarriage circulated around the court, but we cannot be sure if that was the case. It wasn’t until April that Mary was well enough to go outside for some air. As Mary slowly recovered, William became ill, but he too eventually recovered – just in time to meddle with the negotiations for the marriage of Mary’s sister Anne. William preferred Prince George of Hanover – who would eventually become King George I of Great Britain – but Anne married Prince George of Denmark in 1683.

Mary remained popular with the Dutch people and was considered to be one of her husband’s most valuable assets. People reportedly kissed the wheels of her coach and tried to tear off pieces of clothing as she passed, as a souvenir. Over the coming years, William and his father-in-law would become political enemies, and Mary would have to choose between being loyal to her father or being loyal to her husband. Mary’s love for both her husband and her religion made her choose her husband, but it would be a difficult road ahead.

Part three coming soon.

The post Queen Mary II – Princess Lemon (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 15, 2020

Queen Mary II – A royal daughter (Part one)

On 30 April 1661 at one in the morning, the Duchess of York gave birth to a daughter, the future Queen Mary II. Samuel Pepys noted the birth of a royal daughter “at which I find nobody pleased.”1 Mary’s elder brother Charles had died the year before at the age of seven months. At the time of Mary’s birth, her uncle King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland was newly restored to the throne and her father James, Duke of York, was the King’s younger brother and heir. Several more siblings would follow, but only Mary and her younger sister Anne survived to adulthood.

Young Mary spent her early years at St James’s Palace and a house at Twickenham that had been a wedding present to her parents from her maternal grandfather Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon. Her parents’ marriage was anything but happy and her more delicate sister Anne spent time in France in order to find a cure for the trouble with her eyes. The fact that her parents turned to Catholicism alienated them, but Mary and Anne were raised as Anglicans. In 1671, Mary’s mother died of breast cancer in excruciating pain. Neither Mary nor her father attended the funeral – Mary had seen little of her mother.

Although Mary’s uncle had married Catherine of Braganza in 1662, they had remained childless, and so Mary and Anne grew in importance as possible successors to the throne although many feared their father’s Catholic influence on them. The two girls were declared children of the State and an establishment was made for them at Richmond House under the leadership of a governess, Lady Frances Villiers and two Anglican chaplains. In 1673, Mary’s father remarried to the 15-year-old Catholic Mary of Modena, telling his daughters, “I have provided you with a playfellow.”2 Mary of Modena proved to be as unlucky as her predecessor, and she suffered several stillbirths, miscarriages and had short-lived children. Mary became the godmother of her eldest short-lived sister, Catherine Laura, but the girl lived for just ten months. The two Marys became surprisingly close, despite the difference in religion.

Mary grew up somewhat isolated and starved of affection. Nevertheless, she fell in love with Frances Apsley – the daughter of Sir Allen Apsley, to whom she wrote many passionate letters. She wrote, “All the paper books in the world would not hold half the love I have for you, my dearest, dearest, dear Aurelia.”3 They wrote letters back and forth, which were delivered by the dwarf drawing-master Mr Gibstone. Frances was initially flattered by Mary’s attention but later became embarrassed and began to discourage her. Mary was still brooding over Frances when her future husband and first cousin William III, Prince of Orange, arrived at court in the autumn of 1677.

Mary was introduced to her elder cousin and was informed that he would become her husband. Mary broke down immediately and cried for a day and a half. Mary’s father was less pleased with the match but her uncle the King was ready to consent to the match. Despite Mary’s tearful reaction, plans for the wedding went full steam ahead. Mary did not want to leave her stepmother and friend – who was also in the final days of yet another pregnancy – and she was utterly miserable. On 4 November 1677, Mary married William in her bedchamber at 8 in the evening. At 11, the newlyweds withdrew to bed as their uncle quipped, “Now nephew to your work! Hey! St George for England.”4 The following morning, William presented Mary with a small diamond and ruby ring, which she would always treasure.

On 7 November, Mary’s stepmother gave birth to a son named Charles and William was made godfather. Young Charles lived for just two months, but for a moment, he superseded Mary in the line of succession. Cold and blustery weather forced the newlyweds to stay in England longer than William had planned. An outbreak of smallpox did not make this easier either. They finally left England on 19 November as they boarded a barge at Whitehall. Mary continued her weeping, and her sister Anne was unable to say goodbye as she was ill with smallpox – perhaps they would never see each other again. Mary was comforted by Queen Catherine, who had also been sent to a foreign country, but Mary told her, “Madam, you come into England; but I am going out of England.”5

Mary’s uncle and father accompanied her until Erith when the party boarded the yacht Mary. Unfortunately, they were forced to land at Sheerness when they encountered bad weather. A separate ship was sent so they could travel separately and eventually, both arrived at the small village of Ter Heyde, where they were rowed ashore. Later that evening, a coach brought the new Princess of Orange to Honselaarsdijk, which had been made ready for her arrival. Mary’s new life as Princess of Orange was about to begin.

Part two coming soon.

The post Queen Mary II – A royal daughter (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 14, 2020

Lillie Langtry – “The Jersey Lily” (Part two)

Within a month of meeting each other; the Prince of Wales and Lillie were an item, and Lillie was regarded as the Prince’s first official mistress. They were soon seen everywhere together, which their respective spouses hated but could do little about. The pair were physically attracted to each other and had a passionate relationship, but the Prince and Lillie also found kindred spirits in each other as both had come from cold families lacking in love and suffered from low self-esteem.

The Prince of Wales and Lillie liked to spend time together in private away from prying eyes, and so he gave Lillie the gift of a house in Bournemouth, which she decorated to suit their tastes and kept the best room for the Prince. Here the couple could relax and enjoy each other’s company – Lillie often amused the Prince by doing things like wearing lingerie trimmed with royal ermine. Lillie’s husband, left at their London home, was not amused by this sort of behaviour and soon turned to alcohol and became bankrupt. It appears he even tried to divorce Lillie at this time, but the proceedings were eventually stopped – maybe the Prince of Wales intervened to preserve Lillie’s public reputation.

Of course, the Prince of Wales was never a one mistress kind of man, and he soon found new women to entertain him and as he entered into a heavily-publicised relationship with actress Sarah Bernhardt; he paid less and less attention to Lillie Langtry. Lillie was now in a difficult situation; her husband was bankrupt, and the patronage of her lover was waning by the day. The Prince of Wales and Oscar Wilde both suggested that Lillie should become an actress in order to help with her financial difficulties. Though Lillie had never acted before, Oscar Wilde set her up for some training from the actress Henrietta Labouchére, the training and Lillie’s fame were a winning success because her career took off straight away.

(public domain)

(public domain)Lillie went from local amateur dramatics to the West End in a matter of years. She was a sensation, and each performance led to offers of future roles, her greatest success was playing Rosalind in ‘As you like it’. Most of the opening nights were attended by the Prince of Wales, and though their relationship was more or less over, the pair remained close and always wrote to each other and visited each other when they could.

At the end of her relationship with the Prince of Wales, Lillie ended up having a fling with his cousin Prince Louis of Battenberg. She also fell pregnant around this time, and Prince Louis was immediately packed off back to the navy after this and Lillie had to flee back to Jersey with her daughter whom she left on the island with her mother.

In 1882, Lillie parted ways with the Haymarket acting company and formed a company of her own which toured around the UK as well as the US for many years, Lillie gained fame in her own right in the United States as an actress. Lillie took her career as an actress and a businesswoman very seriously and continued to undertake training to improve her acting over the years. She also became the manager of the Imperial Theatre in London, truly breaking the mould for how a society woman should conduct herself in this era. During these years, Lillie was involved in a relationship with a man called Frederick Gebhard with whom she became interested in thoroughbred horse racing. This relationship led to Lillie and Frederick purchasing neighbouring ranches in California, where Lillie gained American citizenship. While in the United States, Lillie was finally divorced from her estranged husband Edward Langtry who died just months later in an asylum.

It was not long before Lillie was married again; she was much like the Prince of Wales in the way she moved swiftly between relationships. Her second marriage was to Hugo Gerald de Bathe; the pair were wed in 1899. Eight years later, Hugo’s father died, and he inherited his baronetcy, making Lillie ‘Lady de Bathe’, and the couple inherited a number of properties and vast amounts of land. Throughout her marriage to Hugo, Lillie continued to act and even appeared in a film in 1913. Little is known of Lillie and Hugo’s marriage, but in later years they lived rather separate lives; Hugo mostly in Venice and Lillie in Monaco, though the pair sometimes attended events together.

Lillie continued to be a fashionable socialite and always drew a crowd wherever she went, even in her later years. As well as performing on stage, working as an artists’ muse, managing stables and running a theatre, Lillie’s fame made her an early form of social influencer and her face was used for the first kind of celebrity endorsements of products such as Pears soap and Browns Iron Bitters.

Lillie’s final stage performance took place in 1917 after almost four decades on the stage. Lillie died in Monte Carlo on 12 February 1925 at the age of 75, leaving much of her remaining wealth to her best friend, Matilda Marie Peat. Lillie’s husband Hugo outlived her and remarried. Lillie left behind a huge legacy in the world of theatre and continues to be remembered in print and film to this day. Lillie also wrote her own memoirs which we can use to look deeper into this fascinating lady who was so much more than a mistress of the Prince of Wales.1

The post Lillie Langtry – “The Jersey Lily” (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Which royal women will we see in The Crown season 4?

With season 4 of the Crown nearly upon us, let’s have a look at the royal women we’ll see in season 4. The fourth season will cover the years 1977 until 1990.

(Screenshot/Fair use)

(Screenshot/Fair use)The Queen – The most obvious royal woman we’ll see will be The Queen as she is the headline act, so to speak. She’ll be portrayed by Olivia Colman and in a flashback by Claire Foy.

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother – The widowed Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother remained an active member of the royal family during these years, and she’ll be portrayed by Marion Bailey.

(Screenshot/Fair use)

(Screenshot/Fair use)Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon – The Queen’s sister divorced in 1978, which I am sure will be covered in the season, and it was already alluded to in the previous season. She’ll be portrayed by the fabulous Helena Bonham Carter.

(Screenshot/Fair use)

(Screenshot/Fair use)Anne, Princess Royal – We’ve already met the sassy Princess in the previous season, and I am sure she’ll continue to wow us this season. She’ll be portrayed by Erin Doherty.

The Duchess of Cornwall – Still known as Camilla Parker Bowles during these years, we’ll see The Duchess of Cornwall portrayed by Emerald Fennell.

Screenshot Trailer/Fair use

Screenshot Trailer/Fair useDiana, Princess of Wales – This season will see the introduction of Lady Diana Spencer, later known as The Princess of Wales as Prince Charles’s wife and Diana, Princess of Wales after their divorce. I expect that her storyline will take over much of the season. She’ll be portrayed by Emma Corrin.

Sarah, Duchess of York – We’ll also see the introduction of Prince Andrew’s wife and later ex-wife Sarah Ferguson. She was known as The Duchess of York during her marriage and as Sarah, Duchess of York after the divorce. She’ll be portrayed by Jessica Aquilina.

The Duchess of Windsor – The fourth season is said to also cover the death of The Duchess of Windsor in 1986. It is unclear who will portray her, but perhaps it will also be Geraldine Chaplin who portrayed her in the third season.

I’m hoping we’ll see some members of the extended family as well like the Duchess of Kent, Princess Michael of Kent and the Duchess of Gloucester.

The post Which royal women will we see in The Crown season 4? appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 12, 2020

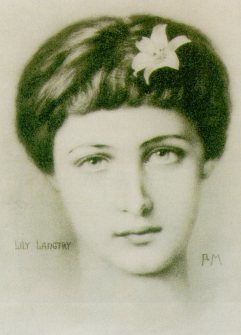

Lillie Langtry – “The Jersey Lily” (Part one)

Emilie Charlotte le Breton, known as Lillie, was born on 13 October 1853 on the channel island of Jersey. We know little of Lillie’s childhood but do know that her parents were Emilie Davis and her husband William Corbet le Breton, who was a reverend.

Lillie was one of seven children and was the only daughter in the bunch. After tormenting her governess, she ended up being educated alongside her brothers, so she received a broader education than most girls in the period. It is said that Lillie grew up running free around the island and playing tricks on people with her brothers, she was often out playing dares and seeking attention to stand out from her brothers; once even streaking in the street at the age of eleven!

As time went on, her father was involved in numerous affairs and her mother started acting quite strangely – she began to take a pet seagull out and about with her and then eventually stopped leaving the house altogether. When Lillie was sixteen, she entered into a romantic relationship with a boy from the island; her father disapproved and tried to break the pair up. When all else failed, William had to admit to Lillie that the boy was in fact her own half-brother who was the product of one of his affairs and the relationship had to be stopped before it led to incest! This child was just one of a string of children in the area that suspiciously had the reverend’s eyes and good looks. After having quite enough of her father’s behaviour and wishing to leave the island, Lillie aimed for a marriage match that would allow her to move away.

In 1874, Lillie had supposedly set her sights on a man named Edward Langtry when he sailed into St Peter Port on a yacht called the Red Gauntlet. Lillie later met the wealthy, recently widowed Edward at a ball and they were married with Lillie’s father acting as Reverend. Many people wondered what Lillie saw in the shy Edward who was called “dull” and a “pudgy chap” and later in life, Lillie exclaimed, “to become the mistress of the yacht I married the owner”. Clearly for her, marrying Edward was a means to an end and a way out of Jersey. Within a few years, Lillie had realised her husband was not as well-off as he first appeared, she was bored on the island, and the pair were frequently bickering. At this point, Lillie got her wish, and the couple moved to the mainland.

In 1876, after living in Southampton for a while, Lillie convinced her husband to move to Belgravia in London in order to aid in her recovery from typhoid fever, Edward hated the idea but agreed, and they quickly began to live separate lives. A year later, Lillie made her first public appearance in London at the home of Lady Sebright, people loved her, and from then on she was a highly sought after guest for dinner parties and balls. Lord Randolph Churchill said she was “a most beautiful creature, quite unknown, very poor and they say she has but one black dress”. It is doubtful that Lillie did own just one dress at this time, but as she was in mourning after the death of her brother Reginald she was often seen in plain black clothing with no jewellery, surrounded by finely dressed women covered in jewels and bows, her natural beauty was allowed to shine.

(public domain)

(public domain)Lillie soon found herself as an artist’s muse – she was sketched by Frank Miles and the prints of this were distributed far and wide. The young Jersey woman was then painted by John Everett Millais and was meeting with the likes of Oscar Wilde. Millais was blown away by Lillie and called her “the most beautiful woman in the world” while Oscar Wilde added that her charm, wit and her mind were her true weapons. Within a year of stepping out into London society, Lillie had somehow become a professional beauty and muse. One portrait of Lillie was displayed at the Royal Academy and had to be cordoned off due to keep the crowds back! Lillie spent her time posing for portraits and photographs which eventually ended up in the hands of the Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Queen Victoria.

While his wife Alexandra was away in Greece, the Prince of Wales asked his fashionable friends to arrange for him to meet with Lillie Langtry. At a dinner party held by Arctic explorer Sir Allen Young, the Prince’s wish was granted and he was introduced to Lillie and her husband, with Lillie being given the title of “the Jersey Lily” a nickname that stuck. The Prince was besotted and arranged to meet Lillie more discreetly the next day, which led to romance. Lillie was shocked by her sudden fame, later writing “surely I thought London had gone mad, for there can be nothing about me to warrant this extraordinary excitement”.1

Part two coming soon.

The post Lillie Langtry – “The Jersey Lily” (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 11, 2020

Viola of Teschen – An unlikely Queen

In 1305, the young king Wenceslaus III of Bohemia wed Viola of Teschen much to the surprise and disapproval of his subjects. For years he had been betrothed to the heiress of Hungary, Elizabeth. He was even still betrothed to her when he married Viola. What made him chose Viola, a daughter of one of his vassals – an insignificant prince with a small duchy over a royal heiress whom he long planned on marrying?

Obscure Background

Practically nothing is known about Viola of Teschen before her marriage. It is hard to determine a birth year for her, but it is usually thought to be in 1290 or 1291. She was probably a little younger than her future husband, Wenceslaus III, who was born in 1289. Even the identity of Viola’s mother is unknown. Viola’s name was quite unusual, and she was probably named after her Bulgarian great-grandmother. Her father was Mieszko I, Duke of Teschen. Viola was born into the Piast dynasty, the same family that ruled Poland. She was from a cadet branch of the family who had little power. Mieszko belonged to the Silesian branch of the Piasts. Over the past century, Silesia was divided between all of the surviving sons of this line, leaving the junior members, such as Mieszko with little land. Viola had two brothers, who in turn would have their father’s small duchy split between them.

The Unexpected Queen

Viola first entered the scene on 5 October 1305, when she married the sixteen-year-old King of Bohemia, Wenceslaus III in Brno, Bohemia. The wedding was performed relatively hastily, and it was not a grand affair like most royal weddings. It remains a mystery why Wenceslaus married Viola, especially since he was already betrothed to a royal heiress. Apparently, Viola was very beautiful, and some thought that was why Wenceslaus chose her. However, this seems to be a romantic exaggeration. There were probably some political motivations behind the marriage as well. Viola’s father’s duchy of Techen was strategically located between Bohemia and Poland – of which Wenceslaus claimed the crown. This marriage could have been an effort to strengthen Wenceslaus’ influence in Poland. Because Viola’s name was odd, she was renamed Elizabeth at the Bohemian court. This was the same thing that happened to her predecessor, Elizabeth-Richeza of Poland, on her marriage.

Four days after the wedding, Wenceslaus broke off his betrothal to Elizabeth of Hungary and renounced his claims to the Hungarian throne. Apparently, the marriage was not very happy. Wenceslaus’ sisters and many of his subjects were not happy that he chose Viola. They considered her too low-born to be a Queen. Wenceslaus was also not a faithful husband. The young king had a reputation for being reckless and a womaniser.

Just ten months later, on 4 August 1306, Wenceslaus was assassinated under mysterious circumstances. Viola was suddenly left a young widow. No children were born from this short-lived marriage, so Bohemia’s royal Premyslid dynasty became extinct. A succession crisis broke out, with Viola’s sisters-in-law, Anne and Elizabeth, as well as her husband’s stepmother, Elizabeth-Richeza of Poland, at the centre of it. However, Viola does not seem to have any involvement with it. Unlike the other women of the Premyslid dynasty, she appears to have been unambitious.

To this day, it remains a mystery as to why Wenceslaus was assassinated, and who ordered the assassination. Some later historians speculated that Viola might have been behind the murder herself, apparently because she felt neglected by the king and disapproved of his lifestyle. However, it is more likely that Wenceslaus’ murder was organised by his rivals for the Polish throne, or Bohemian nobles, who apparently had enough of his reckless rule.

The Forgotten Widowed Queen

Unlike her predecessor, Elizabeth-Richeza of Poland, Viola was not financially secured when she was widowed after a short marriage. Because the wedding was arranged so quickly, there was no contract for Viola to receive a dower or pension if she was widowed. For the next ten years, the whereabouts and activities of Viola are unknown. She most likely took shelter in a monastery, where she may or may not have taken vows. For the next four years, Viola would have seen the Bohemian throne change hands a few more times; first to her older sister-in-law, Anne, and her husband Henry of Carinthia, then to Elizabeth-Richeza, and her second husband, Rudolf of Habsburg, and then back to Anne and Henry, and then finally to her other sister-in-law, Elizabeth, and her husband, John of Luxembourg.

Viola resurfaces in 1316, ten years after her first husband’s death. At this time, Elizabeth of Bohemia and John of Luxembourg were on the Bohemian throne, but they were facing opposition from the other Bohemian Queen Dowager, Elizabeth-Richeza and her lover, Henry of Lipa. John and Elizabeth had Henry of Lipa imprisoned at this time, but they still wanted to win over the support of the most powerful Bohemian nobles. One of them, Peter of Rosenberg, was engaged to Henry’s daughter. It was then decided that he would break off this engagement, and marry the other widowed Queen, Viola, instead.

Viola and Peter of Rosenburg married in 1316. Like Viola’s first marriage, this was also a socially unequal marriage, but this time it was Viola who was the higher-ranking spouse. This marriage increased Peter’s status and won him over to the side of the current king, John. However, like Viola’s first marriage, this one was also short-lived and childless. Viola died just a year later on 21 September 1317, less than thirty years old. She was buried in the Rosenburg family’s vault at Vyssi Brod Monastery.

It is worth mentioning that there are some similarities between Viola and her predecessor, Elizabeth-Richeza of Poland. They both came from the Piast dynasty, but Elizabeth-Richeza was from a more higher-ranking branch. Because their first names were unusual in Bohemia, they were both renamed “Elizabeth” upon their marriages. Unlike Elizabeth-Richeza, Viola never seems to have used this name personally. Also, they were both widowed after short marriages to Bohemian kings. There are also some significant differences between these two Queens too. Elizabeth-Richeza was financially secured when she was widowed, while Viola was not. Elizabeth-Richeza also proved to be a capable and ambitious politician, while Viola faded into obscurity. As a result, Elizabeth-Richeza of Poland made more of a mark on history, while Viola is hidden in the footnotes.1

The post Viola of Teschen – An unlikely Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 10, 2020

The Imprisoned Princess by Catherine Curzon Book Review

Sophia Dorothea of Celle would have been Queen of Great Britain if she had not divorced the future King George I of Great Britain, but it was not to be.

Born from an initially morganatic marriage, she married her first cousin, then Electoral Prince of Hanover, the son of Sophia of Hanover, in order to unite their lines and more importantly their riches. It was an unhappy match from the start with her famously declaring, “I will not marry the pig snout!” But marry they did, and they also managed to produce two children – the future King George II and Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, later Queen in Prussia. Both then took lovers, which spiralled quickly out of control, leading to a divorce and Sophia Dorothea’s imprisonment at Ahlden for the rest of her life.

The Imprisoned Princess by Catherine Curzon delves into her life and even the drama leading up to her birth in a very engaging way. The book well-researched with a ton of references but it still reads like a dream, and you will not want to put it down. Even if you know how it ends, you keep hoping for a different outcome for Sophia Dorothea. I think she would have made a fabulous Queen and it’s quite tragic that she never got see her children again.

The Imprisoned Princess by Catherine Curzon is available now in the UK and the US.

The post The Imprisoned Princess by Catherine Curzon Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.