Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 169

August 28, 2020

Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918 by Helen Azar Book Review

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna of Russia was born on 26 June 1899 (O.S 14 June) as the third daughter of Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna. Tragically, she and her entire family were killed in the early morning of 17 July 1918. Her remains were not identified until 2007 and are still not interred with the rest of the family.

Described as “kindness itself”, Maria’s hopes and dreams for the future have been preserved in her diaries, though not all of them have survived. Helen Azar has translated the surviving letters and diaries painstakingly, and we can now dive into the mind of the young woman who was taken from this earth so brutally. The introduction of the book gives biographical information about Maria before diving into the letters and diaries. Maria herself destroyed many of her diaries and only the years 1912, 1913 and 1916 survive.

Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918 is a lovely look at a forgotten woman, whose remains now lie unceremoniously in a box in an archive. It’s a must-have for any Romanov enthusiast. Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918 by Helen Azar is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post Maria Romanov: Third Daughter of the Last Tsar, Diaries and Letters, 1908–1918 by Helen Azar Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Statue of Diana, Princess of Wales to be installed on her 60th birthday

The statue of Diana, Princess of Wales commissioned by her sons The Duke of Cambridge and The Duke of Sussex, will be installed on 1 July 2021, which would have been her 60th birthday.

The statue was commissioned in 2017 to mark the 20th anniversary of her death and to recognise her positive impact in the United Kingdom and around the world. It will be installed in the Sunken Garden at Kensington Palace. The announcement stated that the “Princes hope that the statue will help all those who visit Kensington Palace to reflect on their mother’s life and her legacy.”

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

The statue has now passed the design stage, but the installation has been delayed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The funds for the statue were raised through public donations with a small committee of close friends and family – including her sister Lady Sarah McCorquodale, working on the project. In December 2017, it was announced that Ian Rank-Broadley had been commissioned to design the statue. It had initially been expected to be completed in 2019.

Diana, Princess of Wales, was married to The Prince of Wales from 1982 until their official divorce in 1996. She was killed in a car accident in Paris the following year.

The post Statue of Diana, Princess of Wales to be installed on her 60th birthday appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 27, 2020

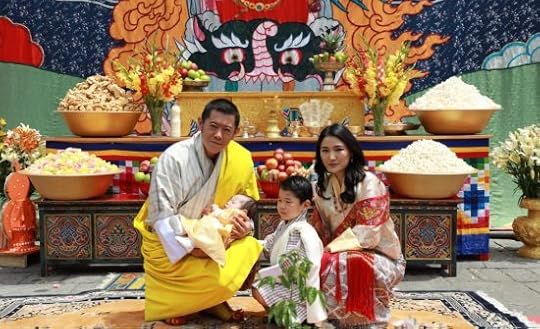

Jetsun Pema of Bhutan – The Dragon Queen

The youngest current Queen consort is the Queen of Bhutan, born Jetsun Pema. She was born on 4 June 1990 as the daughter of Dhondup Gyaltshen and Sonam Choki at the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital in Thimphu. She is their second eldest child of five and thus has four siblings: Thinley Norbu, Jigme Namgyal, Serchen Doma and Yeatso Lhamo.

Jetsun received her primary education at the Little Dragon Montessori School before completing her elementary education at the Sunshine School. She also attended the Lungtenzampa Higher Secondary School, the Changangkha Secondary School and St. Josephs Convent. She completed her high school years at Lawrence Schooll is Sanawar before going to the United Kingdom to attend Regent’s University London where she majored in International Relations with minors in Psychology and Art History. She captained the basketball team at Lungtenzampa and regularly visited art museums while living in London.1

Embed from Getty Images

It is unclear where she met her future husband, but they are distantly related. Their engagement was announced by her future husband, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, the fifth Dragon King of Bhutan, on 20 May 2011 during the opening of Parliament. He said, “As King, it is time for me to marry. After much thought, I have decided that the wedding shall be later this year. As my Queen, I have found such a person and her name is Jetsun Pema. While she is young, she is warm and kind in heart and character. These qualities, together with the wisdom that will come with age and experience, will make her a great servant to the nation.”2

Embed from Getty Images

They were married on 13 October 2011, and during the ceremony the King bestowed the Crown of the Druk Gyaltsuen on her, formally proclaiming her the Queen of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Although Bhutan allows for polygamy, her husband has said he would never marry another woman.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Since becoming Queen, Jetsun has joined her husband on several visits abroad and inside Bhutan. She also is active on social media. She is the Patron of the Royal Society for Protection of Nature, the Ability Bhutan Society, the Bhutan Kidney Association, the Bhutan Kidney Foundation as well as the UNEP Ozone Ambassador and President of the Bhutan Red Cross Society.

Royal Office for Media

Royal Office for MediaOn 11 November 2015, it was announced that Jetsun was expecting their first child and a son was born to them on 5 February 2016. His name, Jigme Namgyel Wangchuck, was announced on 16 April 2016. On 17 December 2019, it was announced that she was expecting their second child. A second son named Jigme Ugyen Wangchuck was born on 19 March 2020.

The post Jetsun Pema of Bhutan – The Dragon Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 26, 2020

Schloss Oldenburg – Memories of resplendence

Schloss Oldenburg stands in the centre of the city of Oldenburg in Germany and served as the residence of the Counts, Dukes and finally, the Grand Dukes of Oldenburg. The oldest part dates from 1607 and it was Anthony Günther, Count of Oldenburg who wanted to develop the medieval buildings into a palace with four wings. The last parts of the medieval castle were demolished in the 18th century.

The Grand Duchy of Oldenburg came to an end in 1918 with the abdication of Frederick Augustus II, Grand Duke of Oldenburg and in 1923 the building was converted into the State Museum of Art and Cultural History in Oldenburg (Landesmuseum) which still uses the Palace today.

Click to view slideshow.

Schloss Oldenburg still displays some of its royal history, though it is not the main focus. When I visited, they had an exhibition on Franz Radziwill, which wasn’t really my taste. Some of the information is also offered in English but not all of it. I loved learning that the Marble Room was where Amalia married King Otto of Greece, that is what brings the rooms alive and I am sure this palace has plenty more stories like that. Perhaps they could expand on this some more. You can buy a day ticket for all three buildings of the Landesmuseum, which includes the Prinzenpalais (also a former royal residence) and the Augusteum (the royal art gallery).

The post Schloss Oldenburg – Memories of resplendence appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 25, 2020

Maria of Orange-Nassau – A forgotten Princess

Maria of Orange-Nassau was born in The Hague on 5 September 1642 as the daughter of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and Amalia of Solms-Braunfels. She would be the youngest of five surviving siblings – several others died in childhood. Unfortunately, we know very little about her youth. She was present at the wedding of her sister Luise Henriette to Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, at the age of four, and she was depicted in the painting that was made of the wedding. She would barely know her father – he died when she was four years old.

(public domain)

(public domain)Two years later, she was also the subject of a painting by Willem van Honthorst, and she is pictured holding a miniature of Luise. It is not clear if she was present for the wedding of her sister Albertine Agnes and William Frederick, Count of Nassau-Dietz, in 1652, but she was definitely present at the wedding of her sister Henriette Catherine to John George II, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau in 1659. She was probably in regular contact with her nephew, the future King-Stadtholder William III, who was born in 1650. Her brother William II, Prince of Orange, died a week before his son was born when Maria was only eight years old. She and William III, Prince of Orange, were also painted together by Gerard van Honthorst in 1653. Maria would grow up with her mother but also often went to visit her sister Albertine Agnes in Leeuwarden.

Her mother had tried to make advantageous matches for all her children and had managed rather well so far. She had even secured a King’s daughter for her eldest son William II. She had tried to secure the future King Charles II of England for Luise Henriette, but that match never took place, and once he was in exile, he was no longer considered a good match. Once back on the throne, Amalia tried to secure him for Maria, but she was beaten by the Portuguese Catherine of Braganza and her immense dowry. A certain Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp was reportedly also considered, but he was vetoed as a drunk.

Maria and William III (public domain)

Maria and William III (public domain)Maria ended up marrying her second cousin Louis Henry, Count Palatine of Simmern-Kaiserslautern, who was a grandson of Louise Juliana of Nassau. The wedding contract was signed in March 1666, but they did not marry until 23 September 1666 in Cleves. At the time, the Orange family was not very popular in the republic, and Cleves was just across the border and the Duchy of Cleves belonged to Brandenburg at the time which meant that Luise Henriette and her husband were there often, as was his governor John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen – also a relative. Therefore, three of the sisters were married in Cleves, rather than in the republic. Their close connection to Cleves is also depicted in a painting of all four sisters with Cleves’ Swan Castle in the background. This was possibly painted in 1666 when they were all there for Maria’s wedding.

The newlyweds moved to Kreuznach (now known as Bad Kreuznach), where they used the Pfalz-Simmerner Hof as a residence. The marriage would last just seven years as Louis Henry died in early 1674 of some sort of infectious disease, and he and Maria had had no children together. Louis Henry’s lands fell to Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine (father of the formidable Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine). Maria was allowed a dower property in Kreuznach and had the Oranienhof built from the ruins of a convent. Unfortunately, Oranienhof was demolished at the beginning of the 19th century.

(public domain)

(public domain)After her husband’s death, Maria often went home to the Netherlands, such as when her nephew William fell ill with the chickenpox in 1675. The thoughtful visit led to Maria becoming infected as well, and she was reportedly very ill for a while. She was probably still in the Netherlands when her mother Amalia died just a few months after William’s illness. William inherited the Lordship and the castle of Turnhout from Amalia, which he gave in usufruct to his aunt Maria. Maria would visit the castle often and continued the restorations begun by Amalia.

Maria died at Kreuznach on 20 March 1688 after suffering from pneumonia for six days. Although she had asked to be buried at Turnhout on her deathbed, she was buried in the newly created crypt in the Stephanskirche in Simmern, where her husband had also been buried. Their sarcophagi have been damaged over time, but they are still there.1

The post Maria of Orange-Nassau – A forgotten Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 24, 2020

Archduchess Assunta of Austria – The beautiful princess who wanted to be a nun

Assunta Alice Ferdinandine Blanca Leopoldina Margarethe Beatrix Raphaela Michaela Philomena was born on 10 August 1902 to Archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria and Infanta Blanca of Spain as their eighth child out of ten.

Public domain via Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

Public domain via Österreichische NationalbibliothekThe household full of children – the ten brothers and sisters were very close in age, and every year their parents seemed to be welcoming a new addition to their family – was by all accounts a happy one. Their main residence was the Palais Toskana in the district of Wiede in Vienna, and the family was spending vacations in Italy where their mother, Infanta Blanca, owned property. It was a multicultural family with ties that stretched across the main royal families in Europe. Assunta was particularly close to her sister, Maria Antonia, but she also enjoyed the company of her other brothers and sisters and lived an idyllic childhood until the age of 16.

Following the First World War, the Habsburg dynasty was removed from the throne of the Austrian Empire, and this marked the moment when the life of the family changed forever. The members of the royal family were not treated kindly by the new republican Austrian government, which confiscated all their property, leaving them without a source of income. Assunta was only sixteen years old, and she saw her family ripped apart. Her older brothers, Archdukes Ranier and Leopold, chose to remain in Austria and they recognised the new republic while the rest of the family moved to Spain, settling in Barcelona and living with very limited means.

Assunta and her sister Maria Antonia found refuge in religion. Their parents were observant Catholics, but they felt the newly found religious drive of their two daughters might be a bit worrisome. Maria Antonia had a change of heart and married a Spanish aristocrat, while Assunta was determined to become a nun. Her parents were opposed to this decision, but after she ran away to South Africa aboard a ship, they accepted her desire to join a religious order. She entered the convent of St. Teresa de Tortosa near Barcelona, but it was not meant to be. The Spanish Civil war started, and the convent was attacked. The nuns were forced to flee, and those who hadn’t taken their vows yet were advised to go back to their families – Assunta was one of them.

Back at her family’s home, she had time to think and re-assess her life, and in the 1930s, one of her brothers introduced her to a Polish Jewish doctor, Joseph Hopfinger. He fell in love with the beautiful girl who wanted to become a nun and convinced her to marry him despite the opposition of Infanta Blanca who would have liked to see her daughter making an aristocratic marriage.

The young couple didn’t have much time to enjoy their life together as Joseph was called into the service of the army until the fall of France. The First World War stole Assunta’s happy childhood life and her royal status in Austria; now another war was threatening to destroy her marriage. When they heard that the Russians had killed his parents in Ukraine, Assunta and Joseph decided to leave Europe. Assunta’s brother Leopold and Franz Joseph were already in the United States and managed to help the young couple emigrate to New York. Joseph quickly found work as a doctor, and their second daughter was born there. Maria Teresa and Juliet Elisabeth Maria Assunta brought happiness to their family, but couldn’t prevent their parents’ divorce in 1950. Assunta’s family believed that Joseph was after her fortune and when he realised that his wife didn’t possess any, he became disenchanted with the marriage.

Assunta never remarried. She lived all her life in the United States and was an active member of the Catholic Church working tirelessly for its charities. She died at the age of 90 on 24 January 1993.

The post Archduchess Assunta of Austria – The beautiful princess who wanted to be a nun appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 23, 2020

Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein – The last Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein was born at Grünholz Castle on 31 December 1885 as the daughter of Frederick Ferdinand, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg and his wife Princess Karoline Mathilde of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg. She would be the eldest of six children and was followed by Alexandra Victoria (born 21 April 1887), Helena Adelaide (born 1 June 1888), Adelaide (born 19 October 1889), Wilhelm Friedrich (born 23 August 1891) and Karoline Mathilde (born 11 May 1894). Her mother was a younger sister of Augusta Victoria, the last German Empress.

Unfortunately, not much is known about her youth. At the age of 19, she was introduced to her future husband, Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, by her uncle Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany at a winter ball in Berlin. They apparently enjoyed spending time together and soon agreed to marry. In May 1905, the engaged couple travelled to England to visit Charles Edward’s uncle King Edward VII, and Charles Edward was appointed to be Colonel in Chief of the Seaforth Highlander Regiment. Charles Edward was the posthumous son of Prince Leopold, the youngest son of Queen Victoria, and was not initially meant to be the heir to the duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. When fate changed, his mother commented bleakly, “I have always tried to bring Charlie up as a good Englishman, and now I have to turn him into a good German.”1 And a good German needs a good German wife.

They were married at Victoria Adelaide’s ancestral home of Schloss Glücksburg with the Emperor in attendance on 11 October 1905. Prince Arthur of Connaught represented the British royal family. The newlyweds would make a routine of spending December to April living in Gotha and May to November living in Coburg. They also had a hunting lodge in Reinhardsbrunn and mountain retreats Schloss Greinburg and Schloss Hinbterriss. They also made many trips to royal relatives in Germany and had yacht cruises from the harbour at Kiel. It was said to have been a happy marriage.2 Victoria Adelaide’s nickname in the family was “Dick.”3

Their first child, a son named Johann Leopold, was born on 2 August 1906, followed by Sibylla (born 18 January 1908), Hubertus (born 24 August 1909), Caroline Mathilde (born 22 June 1912) and Friedrich Josias (born 29 November 1918). As was usual, Victoria Adelaide left the raising of her children to nannies and governesses.

Embed from Getty Images

Victoria Adelaide, as opposed to her husband who preferred to socialise in his own circles, often walked through the towns and listened to the concerns of the people of the duchy. She soon appeared to know everyone personally.

By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R14326 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikimedia Commons

By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R14326 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikimedia CommonsThe family often spoke English at home, and they spent several weeks a year in England. They were at Windsor and Edinburgh in 1907. In December 1908, they spent the holidays at Claremont House and then travelled to Sandringham to visit King Edward VII and to hunt pheasants. In 1910, they once again travelled to England to attend the funeral of King Edward VII and Victoria Adelaide’s husband marched behind the King’s coffin in the funeral procession. They returned in 1911 to visit Charles Edward’s mother and to participate in the coronation parade for the new King George V. In 1913, they visited Charles Edward’s mother again with their two eldest children.

By 1914, life as they knew it was coming to an end and they would soon find themselves on opposing sides of a world war. The family was in England because Charles Edward had been awarded an honorary degree by Oxford University when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo. Charles Edward, who was also a German Army officer, returned to Germany with his family on 9 July. The next four years would prove devastating for not only the family relations, but it would also prove to be the end of the duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was forced to abdicate as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in November 1918, but he delayed it as Victoria Adelaide was pregnant and he feared his family would suffer the same fate as the Romanovs. He was eventually convinced when it was reported that the citizens had no ill will against the family. They were ultimately allowed to keep many properties and were able to preserve much of their wealth. Charles Edward was also deprived of his English titles in 1919.4

Despite no longer reigning, the family remained a political influence, and nationalistic views became very prominent in the following years. In October 1922, Victoria Adelaide and Charles Edward were the honoured guests at a gala dinner of the Deutscher Tag where Charles Edward also met Adolf Hitler. The couple became enthusiastic supporters of the Nazis in the following years. They were known to have anti-Semitic opinions and actively supported organisations whose aim it was to remove Jews from German society. By 1933, the swastika flag was flying over Veste Coburg. But while Charles Edward rose in the Nazi ranks, Victoria Adelaide became disillusioned with the Nazis and began to defy her husband. The Confessing Church, which she supported, was adamantly opposed to the killing of the handicapped in the euthanasia program. It is unclear if she knew of her relative being gassed at Schloss Hartheim in 1941.

After the Second World War, the Allies began a process called “denazification”, and many expected that Charles Edward, who had held high positions during the war, would be classed as a category 1 offender, which was considered the “most guilty.” Other categories were 2: heavily involved, 3: members, less involved, 4: fellow travellers, 5: non-members. Victoria Adelaide was called to testify against her husband, and she said that he had agreed with Hitler’s efforts to lead the German people out of their misery. He stayed loyal because he believed peace would eventually be achieved. He did not abandon Hitler even after the original goals had been compromised. The trial was eventually suspended because Charles Edward was diagnosed with a malignant tumour near his left eye, which required radiation therapy. This left his skin severely burned, and he often wore an eye patch after this. In 1948, he was finally classified as a category 3, and he was fined 2000 Reich marks. He was classified as a category 4 offender after his appeal. Victoria Adelaide later said in an interview that her husband had “stumbled over his own idealism.”

Disillusioned and ill, Charles Edward lived in seclusion at Coburg until his death on 6 March 1954. Victoria Adelaide and four of their children survived him. Prince Hubertus had been killed in 1943. Not much is known of Victoria Adelaide following the Second World War. She moved to Austria where she still owned Schloss Greinburg, and she died there on 3 October 1970.5

The post Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein – The last Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 22, 2020

A look at Queen Silvia of Sweden

Sweden’s consort was born as Silvia Renate Sommerlath on 23 December 1943 in Heidelberg, Germany, to Walther and Alice Sommerlath.

The half-German and half-Brazilian grew up with three older brothers – Ralph, Walther, and Jörg – in their mother’s native Brazil and their father’s native Germany.

The family spent time in São Paulo, Brazil, from 1947 to 1957. During their ten years in Alice Sommerlath’s hometown, Walther worked the President of the Brazilian subsidiary of Swedish company Uddeholm, as well as other positions at the business.

Silvia was educated at the German private and bilingual Colégio Visconde de Porto Seguro before returning to West Germany. She completed her education in Düsseldorf in 1963 and went on to study at the Munich School of Interpreting from 1965 to 1969. There, she focused on the Spanish language, which would lead her to a job at the Argentinean Consulate in Munich as an interpreter.

The 1972 Summer Olympic Games in Munich would change her life. Silvia, a polyglot, was working as an interpreter at the Games where she encountered the Crown Prince of Sweden, Carl Gustaf. He asked her out on a date, and that same evening they had dinner. The pair said that they “just clicked” upon meeting.

Embed from Getty Images

Carl Gustaf became the King of Sweden the next year, and his relationship with Silvia was still going strong. They were photographed by the Swedish media together in the country in 1973, but the media believed she was Margareta of Romania, as the King had been linked to her in the past.

The pair continued to meet up around Europe in places like Switzerland and France. By 1974, Silvia relocated to Stockholm and moved into an apartment owned by Car Gustaf’s older sister, Princess Christina.

Carl Gustaf and Silvia dated for four years before becoming engaged. He had proposed with Princess Sibylla’s – his late mother – engagement ring, and their betrothal was announced on 12 March 1976. During their engagement interview, Silvia showed that she was already in the process of learning Swedish – her sixth language. She also speaks German, Portuguese, English, Swedish, Spanish and French.

Their engagement announcement was postponed to allow Silvia, who was working as the Deputy Head of Protocol of the Organizing Committee in 1976 for the Winter Olympic Games in Innsbruck, Austria, to finish her Olympic role.

Embed from Getty Images

The couple wed on 19 June 1976 at Stockholm Cathedral, just two days after she had become a Swedish citizen. It was the first of a reigning Swedish monarch since 1797.

The couple lived in an apartment in the Royal Palace of Stockholm during their first years of married life, and the King’s older sisters helped Silvia learn the ropes of royal life. Queen Silvia has said that all of his sisters were helpful but has specifically pointed out Princess Christina for always being someone to lean on.

Embed from Getty Images

Carl Gustaf and Silvia welcomed their first child, Princess Victoria, on 14 July 1977 at Karolinska University Hospital. Their second child, Crown Prince Carl Philip, was born on 13 May 1979; however, Carl Philip was only the heir to the throne for a few months because the Swedish constitution was due to be changed.

In January 1980, the laws of succession were changed to absolute primogeniture and were retroactive, meaning that Carl Philip lost his status as heir to the throne. The King and Queen’s firstborn child, Victoria then became the Crown Princess of Sweden.

A third child for the couple, Princess Madeleine, was born on 10 June 1982, and the family relocated to Drottningholm Palace ahead of her birth.

The Swedish Royal Family at Drottningholm Palace in 1984. Photo: Håkan Lind, The Royal Court, Sweden

The Swedish Royal Family at Drottningholm Palace in 1984. Photo: Håkan Lind, The Royal Court, SwedenQueen Silvia has been passionate about charity work, especially regarding children and the elderly with dementia. In 1999, she founded the World Childhood Foundation, which aims to support children who have been victims of abuse and sexual exploitation, street children, children in alternative care and families at risk. Princess Madeleine works alongside her with the charity.

Silvia’s full list of patronages can be viewed here. A list of honorary doctorates and awards she’s won can be found here.

The Queen’s father died in 1990, and her mother passed away from dementia in 1997. She lost her brother, Jörg in 2006.

Queen Silvia is a proud and devoted grandmother to seven grandchildren: Princess Estelle and Prince Oscar (through Crown Princess Victoria and her husband, Prince Daniel), Princes Alexander and Gabriel (through Prince Carl Philip and his wife, Princess Sofia), and Princesses Leonore and Adrienne and Prince Nicolas (through Princess Madeleine and her husband, Chris O’Neill).

The post A look at Queen Silvia of Sweden appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 21, 2020

Book News September 2020

Forbidden Wife: The Life and Trials of Lady Augusta Murray

Hardcover – 1 September 2020 (US) & 3 February 2020 (UK)

On the night of 4 April 1793, two lovers were preparing to compel a cleric to perform a secret ceremony. The wedding of the sixth son of King George III to the daughter of the Earl of Dunmore would not only be concealed—it would also be illegal. Lady Augusta Murray had known Prince Augustus Frederick for only three months, but they had fallen deeply in love and were desperate to be married. However, the Royal Marriages Act forbade such a union without the King’s permission, and going ahead with the ceremony would change Augusta’s life forever. From a beautiful socialite, she became a social pariah; her children were declared illegitimate, and her family was scorned. Forbidden Wife uses material from the Royal Archives and the Dunmore family papers to create a dramatic biography set in the reigns of Kings George III and IV against the background of the American and French Revolutions.

Royal Witches: Witchcraft and the Nobility in Fifteenth-Century England

Hardcover – 1 September 2020 (US) & 4 May 2020 (UK)

Until the mass hysteria of the seventeenth century, accusations of witchcraft in England were rare. However, four royal women, related in family and in court ties―Joan of Navarre, Eleanor Cobham, Jacquetta of Luxembourg and Elizabeth Woodville―were accused of practising witchcraft in order to kill or influence the King.

Some of these women may have turned to the “dark arts” in order to divine the future or obtain healing potions, but the purpose of the accusations was purely political. Despite their status, these women were vulnerable because of their gender, as the men around them moved them like pawns for political gains.

In Royal Witches, Gemma Hollman explores the lives and the cases of these so-called witches, placing them in the historical context of fifteenth-century England, a setting rife with political upheaval and war. In a time when the line between science and magic was blurred, these trials offer a tantalizing insight into how malicious magic would be used and would later cause such mass hysteria in centuries to come.

The Family Medici: The Hidden History of the Medici Dynasty

Paperback – 8 September 2020 (US & UK)

Having founded the bank that became the most powerful in Europe in the fifteenth century, the Medici gained massive political power in Florence, raising the city to a peak of cultural achievement and becoming its hereditary dukes. Among their number were no fewer than three popes and a powerful and influential queen of France. Their influence brought about an explosion of Florentine art and architecture. Michelangelo, Donatello, Fra Angelico, and Leonardo were among the artists with whom they were socialized and patronized.

Thus runs the “accepted view” of the Medici. However, Mary Hollingsworth argues that the idea that the Medici were enlightened rulers of the Renaissance is a fiction that has now acquired the status of historical fact. In truth, the Medici were as devious and immoral as the Borgias―tyrants loathed in the city they illegally made their own. In this dynamic new history, Hollingsworth argues that past narratives have focused on a sanitized and fictitious view of the Medici―wise rulers, enlightened patrons of the arts, and fathers of the Renaissance―but that in fact their past was reinvented in the sixteenth century, mythologized by later generations of Medici who used this as a central prop for their legacy.

Hollingsworth’s revelatory re-telling of the story of the family Medici brings a fresh and exhilarating new perspective to the story behind the most powerful family of the Italian Renaissance.

Queen of the World: Elizabeth II: Sovereign and Stateswoman

Paperback – 8 September 2020 (US)

On today’s world stage, there is one leader who stands apart from the rest. Queen Elizabeth II has seen more of the planet and its people than any other head of state and has engaged with the world like no other monarch in modern history.

The iconic monarch never ventured further than the Isle of Wight until the age of 20 but since then has now visited over 130 countries across the globe in the line of duty, acting as diplomat, hostess and dignitary as the world stage as changed beyond recognition. It is a story full of drama, intrigue, exotic and sometimes dangerous destinations, heroes, rogues, pomp and glamour, but at the heart of it all a woman who’s won the hearts of the world.

The Tsarina’s Lost Treasure: Catherine the Great, a Golden Age Masterpiece, and a Legendary Shipwreck

Hardcover – 1 September 2020 (US) & 15 October 2020 (UK)

On October 1771, a merchant ship out of Amsterdam, Vrouw Maria, crashed off the stormy Finnish coast, taking her historic cargo to the depths of the Baltic Sea. The vessel was delivering a dozen Dutch masterpiece paintings to Europe’s most voracious collector: Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia. Among the lost treasures was The Nursery, an oak-panelled triptych by Leiden fine painter Gerrit Dou, Rembrandt’s most brilliant student and Holland’s first international superstar artist. Dou’s triptych was long the most beloved and most coveted painting of the Dutch Golden Age, and its loss in the shipwreck was mourned throughout the art world.

The Crown in Focus: Two Centuries of Royal Photography

Hardcover – 1 September 2020 (US & UK)

Crown on Camera traces the remarkable relationship between the British Royal Family and photography over the course of nearly 200 years. From Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s enthusiastic adoption of the emerging technology in the mid-19th century to the use of Instagram by the modern monarchy. Today, photographs of the British Royal Family remain some of the most widely distributed images across the world. Featuring iconic formal portraits alongside little-known pictures from private collections, this fascinating book explores how each new development of the medium has been embraced to record royal life.

Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England

Hardcover – 19 September 2020 (US) & 10 June 2020 (UK)

From seventh-century Northumbria to eleventh-century Wessex and making extensive use of primary sources, Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England examines the lives of individual women in a way that has often been done for the Anglo-Saxon men but not for their wives, sisters, mothers and daughters. It tells their stories: those who ruled and schemed, the peace-weavers and the warrior women, the saints and the sinners. It explores and restores their reputations.

Sex and the City of Ladies: Rewriting history with Cleopatra, Lucrezia Borgia and Catherine the Great

Kindle Edition – 3 September 2020 (US)

Hardcover – 3 September 2020 (UK)

In 1450 Christine de Pisan took up the pen to defend her maligned sex. Her book, The City of Ladies, was built around preserving women’s reputations from the slights and misunderstandings of history. In it, the author is visited by three spirits – Justice, Rectitude and Reason – who guide her in sifting through countless lives, in search of worthy citizens.

Nearly 600 years later, the historian and novelist Lisa Hilton picks up the book and promptly falls asleep, only to be visited by three great women from history: Cleopatra, Lucrezia Borgia and Catherine the Great. And they aren’t happy. Having found themselves barred from the original ‘City of Ladies’, they want to know why. And isn’t it time, they ask, for a new author to take up the pen?

What follows is a reassessment of the past, in which deeds and reputations, rumours and reality are held up to the light, and history is wrested back from the distortions of misogyny.

Uncrowned Queen: The Fateful Life of Margaret Beaufort, Tudor Matriarch

Paperback – 17 September 2020 (UK)

As the battle for royal supremacy raged between the houses of Lancaster and York, Margaret Beaufort, who was descended from Edward III and proved to be a critical threat to the Yorkist cause, was forced to give up her son – she would be separated from him for fourteen years. Surrounded by conspiracies in the enemy Yorkist court, Margaret remained steadfast, only just escaping the headman’s axe as she plotted to overthrow Richard III and secure her son the throne. Against all odds, in 1485 Henry Tudor was victorious on the battlefield at Bosworth. Margaret’s unceasing efforts and royal blood saw her son crowned King Henry VII, and Margaret became the most powerful woman in England.

Nicola Tallis unmasks the many myths that have attached themselves to Margaret and reveals the real woman: an independent and vibrant character, who would risk everything to become Queen in all but name.

Fabulously Feisty Queens: 15 of the brightest and boldest women who have ruled the world

Hardcover – 3 September 2020 (UK)

From ancient empresses and warrior queens to fearsome pirates and modern-day monarchs, Fabulously Feisty Queens explores the lives and legacies of history’s most powerful women.

Made of stronger stuff than beauty and grace, discover just how bright, brave, brilliant and clever the world’s female rulers have been throughout the centuries.

With a foreword by historian and Chief Curator at Historic Royal Palaces, Lucy Worsley and illustrations by Pauline Reeves.

Plantagenet Queens & Consorts: Family, Duty and Power

Paperback – 1 August 2020 (US) & 15 September 2020 (UK)

Plantagenet Queens and Consorts examines the lives and influence of 10 figures, comparing their different approaches to the maintenance of political power in what is always described as a man’s world. On the contrary, there is strong evidence to suggest that these women had more political impact than those who came later—with the exception of Elizabeth I—right up to the present day. Beginning with Eleanor of Provence, loyal spouse of Henry III, the author follows the thread of queenship: Philippa of Hainault, Joan of Navarre, Katherine Valois, Elizabeth Woodville, and others, to Henry VII’s Elizabeth of York. These are not marginal figures. Arguably, the “She-Wolf'”, Isabella of France, had more impact on the history of England than her husband Edward II. Elizabeth of York was the daughter, sister, niece, wife, and mother of successive kings of England. As can be seen from the names, several are ostensibly “outsiders” twice over, as female and foreign. With specially commissioned photographs of locations and close examination of primary sources, Steven Corvi provides a new and invigorating perspective on medieval English (and European) history.

Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia: Brother and Sister of History’s Most Vilified Family

Hardcover – 30 September 2020 (UK) & 19 December 2020 (US)

Myths and rumour have shrouded the Borgia family for centuries – tales of incest, intrigue and murder have been told of them since they themselves walked the hallways of the Apostolic Palace. In particular, vicious rumour and slanderous tales have stuck to the names of two members of the infamous Borgia family – Cesare and Lucrezia, brother and sister of history’s most notorious family. But how much of it is true, and how much of it is simply rumour aimed to blacken the name of the Borgia family? In the first-ever biography solely on the Borgia siblings, Samantha Morris tells the true story of these two fascinating individuals from their early lives, through their years living amongst the halls of the Vatican in Rome until their ultimate untimely deaths. Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia begins in the bustling metropolis of Rome with the siblings ultimately being used in the dynastic plans of their father, a man who would become Pope, and takes the reader through the separate, yet fascinatingly intertwined, lives of the notorious siblings. One tale, that of Cesare, ends on the battlefield of Navarre, whilst the other ends in the ducal court of Ferrara. Both Cesare and Lucrezia led lives full of intrigue and danger, lives which would attract the worst sort of rumour begun by their enemies. Drawing on both primary and secondary sources Morris brings the true story of the Borgia siblings, so often made out to be evil incarnate in other forms of media, to audiences both new to the history of the Italian Renaissance and old.

Joan, Lady of Wales: Power and Politics of King John’s Daughter

Hardcover – 30 September 2020 (UK) & 19 December 2020 (US)

The history of women in medieval Wales before the English conquest of 1282 is one largely shrouded in mystery. For the Age of Princes, an era defined by ever-increased threats of foreign hegemony, internal dynastic strife and constant warfare, the comings and goings of women are little noted in sources. This misfortune touches even the most well-known royal woman of the time, Joan of England (d. 1237), the wife of Llywelyn the Great of Gwynedd, illegitimate daughter of King John and half-sister to Henry III. With evidence of her hand in thwarting a full-scale English invasion of Wales to a notorious scandal that ended with the public execution of her supposed lover by her husband and her own imprisonment, Joan’s is a known, but little-told or understood story defined by family turmoil, divided loyalties and political intrigue. From the time her hand was promised in marriage as the result of the first Welsh-English alliance in 1201 to the end of her life, Joan’s place in the political wranglings between England and the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd was a fundamental one. As the first woman to be designated Lady of Wales, her role as one a political diplomat in early thirteenth-century Anglo-Welsh relations was instrumental. This first-ever account of Siwan, as she was known to the Welsh, interweaves the details of her life and relationships with a gendered reassessment of Anglo-Welsh politics by highlighting her involvement in affairs, discussing events in which she may well have been involved but have gone unrecorded and her overall deployment of royal female agency.

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia: The Philosopher Princess

Paperback –15 September 2020 (US & UK)

Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618-1680) was the daughter of the Elector Palatine, Frederick V, King of Bohemia, and Elizabeth Stuart, the daughter of King James VI and I of Scotland and England. A princess born into one of the most prominent Protestant dynasties of the age, Elisabeth was one of the great female intellectuals of seventeenth-century Europe. This book examines her life and thought. It is the story of an exiled princess, a grief-stricken woman whose family was beset by tragedy and whose life was marked by poverty, depression, and chronic illness. It is also the story of how that same woman’s strength of character, unswerving faith, and extraordinary mind saw her emerge as one of the most renowned scholars of the age. It is the story of how one woman navigated the tumultuous waters of seventeenth-century politics, religion, and scholarship, fought for her family’s ancestral rights, and helped establish one of the first networks of female scholars in Western Europe. Drawing on her correspondence with René Descartes, as well as the letters, diaries, and writings of her family, friends, and intellectual associates, this book contributes to the recovery of Elisabeth’s place in the history of philosophy. It demonstrates that although she is routinely marginalized in contemporary accounts of seventeenth-century thought, overshadowed by the more famous male philosophers she corresponded with or dismissed as little more than a “learned maiden,” Elisabeth was a philosopher in her own right who made a significant contribution to modern understandings of the relationship between the body and the mind, challenged dominant accounts of the nature of the emotions, and provided insightful commentaries on subjects as varied as the nature and causes of illness to the essence of virtue and Machiavelli’s The Prince.

Domina: The Women Who Made Imperial Rome

Paperback – 20 October 2020 (US) & 22 September 2020 (UK)

Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—these are the names history associates with the early Roman Empire. Yet, not a single one of these emperors was the blood son of his predecessor. In this captivating history, a prominent scholar of the era documents the Julio-Claudian women whose bloodline, ambition and ruthlessness made it possible for the emperors’ line to continue.

Eminent scholar Guy de la Bédoyère, author of Praetorian, asserts that the women behind the scenes—including Livia, Octavia, and the elder and younger Agrippina—were the true backbone of the dynasty. De la Bédoyère draws on the accounts of ancient Roman historians to revisit a familiar time from a completely fresh vantage point. Anyone who enjoys I, Claudius will be fascinated by this study of dynastic power and gender interplay in ancient Rome.

The post Book News September 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 20, 2020

Margaret Plantagenet – A traitor’s daughter (Part two)

Margaret threw herself into renovating and commissioning new residences, like Warblington Castle. From a later inventory, we know that over 73 servants worked at Warblington Castle alone. She proudly displayed her arms on the windows of her properties.

Her influence at court grew even more significant when she was chosen to be one of the godmothers of Princess Mary. She was later also appointed governess to Mary which would lead to an affectionate friendship with the future Queen. Margaret held the post from 1520-1521 and again from 1525 until 1533.

Slowly Margaret’s children began to get married and have children of their own. Her eldest son married Jane Neville – a distant kinswoman, Arthur married a young widow named Jane Pickering, Geoffrey married Constance Pakenham, and Ursula married Henry Stafford, 1st Baron Stafford – heir to the Duke of Buckingham. Reginald would eventually become the last Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury. Margaret was on top, her children had made advantageous marriages, and she was in high favour with the King and Queen. Margaret made sure her family found places at court, such as her granddaughter Catherine who was in Princess Mary’s household and was of a similar age.

Meanwhile, her son Reginald watched from Padua as King Henry VIII broke from Rome to marry Anne Boleyn. He avoided the situation until he was directly asked about it in 1535. Margaret had tried to protect Mary from the situation as much as she could as her governess and tried to keep everything as normal as possible for her. By 1528, Mary’s household was recalled from Wales, and it was reduced, but Margaret remained in her post. When Henry finally left Catherine for good in 1531, there was no more point in hiding it from Mary. In private, Mary was often emotional, and this situation also coincided with the onset of puberty. When Princess Mary was declared illegitimate in 1533, her household was disbanded. Margaret asked to serve Mary at her own cost, but this was not allowed. Perhaps Henry believed that Margaret had influenced Mary’s behaviour in refusing to recognise her reduced status. When the Imperial Ambassador requested that Mary should once again be placed with Margaret, Henry told him that “the Countess was a fool, of no experience, and that if his daughter had been under her care during this illness, she would have died, for she would not have known what to do.”1

Margaret and Mary had spent eight years together, and being forcibly separated must have been painful for them. According to the Imperial Ambassador, Mary considered Margaret to be “her second mother.”2 Margaret was by now 60 years old, and she had some sort of collapse after being separated from Mary. Margaret decided to maintain a low-profile for the next three years, and she was not with Catherine when she died on 7 January 1536 in exile at Kimbolton Castle. Her response to her close friend’s death has not been recorded. The downfall of Anne Boleyn happened just four months later, and Henry duly married his third wife Jane Seymour 11 days after Anne Boleyn’s execution. Mary was eventually allowed back to court after completely submitting to her father’s will, and Margaret also returning to court.

Meanwhile, Reginald’s opinion on the Boleyn marriage arrived rather a bit late and with awkward timing just as Margaret returned to court. Her other son Henry advised Margaret to condemn Reginald as a traitor. That summer, Margaret withdrew from court again. She kept in touch with Mary, and she spent most of her time at Warblington Castle. Her sons’ favour with the King fluctuated quite a bit during this time. Henry hated Reginald and was sorely tested by Geoffrey’s foolish behaviour. By 1538, only Henry remained at court, but his loyalty too was a facade.

On 29 August 1538, Geoffrey was arrested and taken to the Tower of London. On 4 November, Henry joined his brother in the Tower. On 12 November, the Earl of Southampton and the Bishop of Ely arrived to interrogate Margaret, and she was escorted to the Earl of Southampton’s residence three days later. Reginald was out of the King’s reach, and her other son Arthur had already passed away. On 9 December 1538, Henry was executed for treason as he “wished and desired the King’s death.” Geoffrey avoided execution and was pardoned the following year.

Margaret was examined for several days and defended herself and her sons. Reginald cast his family in the role of martyrs for the Church, and there were even several international responses to the arrests. To keep her lands under his own control, Henry kept Margaret imprisoned, but he did not execute her. Even her young grandson Henry (son of the elder Henry) was kept imprisoned. Margaret continued to maintain her innocence, but she was taken to the Tower by November 1539, where she was held for several years. She was allowed some freedom to walk about, but she suffered from the cold.

The end came quite suddenly on 27 May 1541, and Margaret was “beheaded in a corner of the Tower, in presence of so few people that until evening the truth was doubted.”3 It appeared to have been a spur of the moment decision on Henry’s part and Margaret was not informed until that very morning. She was shocked and “found the thing very strange, not knowing of what crime she was accused, nor how she had been sentenced.”4 On the scaffold, she sent Princess Mary her blessing and begged for hers in return. The inexperienced executioner “hacked her head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner.”5 She was buried in the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower.

In 1886, Margaret was beatified by Pope Leo XIII and she is now known as Blessed Margaret Pole.6

The post Margaret Plantagenet – A traitor’s daughter (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.