Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 177

June 10, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of William, Prince of Orange

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands would never know her elder half-brother as he died a year before she was born, but for a long time, it was he who was meant to be King.

William was born on 4 September 1840, shortly before the abdication of his great-grandfather, King William I of the Netherlands. He was thus born third in the line of succession, behind his grandfather and father. Being yet another William, he was nicknamed Wiwill in the family. His parents were the future King William III of the Netherlands and his first wife, Sophie of Württemberg. His parents were famously mismatched, and he would grow up in an evergrowing battle. Yet, they managed to have two more sons. Maurice was born in 1843, but he would die in infancy. Alexander was born in 1851.

William grew up to be quite the hothead, and his mother spoiled him much to his father’s dismay. Perhaps it is no surprise as he was often witnessing violent arguments. Once, Sophie had to wear long gloves for weeks after her husband scratched her arms. From the age 7, William’s day was planned out to the minute for his education. In 1849, his grandfather died quite suddenly, and his father reluctantly became King William III. Young William was now formally heir to the throne and the Prince of Orange. His more delicate younger brother Maurice fell ill with meningitis in early 1850, and he died at the age of six on 4 June 1850. His devastated mother left to take a cure, and William was left with his governor. His father found solace with a mistress.

Nevertheless, his warring parents managed to make up long enough for Sophie to fall pregnant for the third time. As the situation in the palace deteriorated, it was decided to send William to boarding school. his younger brother Alexander was born on 25 August 1851.

Despite Sophie’s despair of William’s leaving, the boarding school actually did him some good. Sophie’s visits to him were limited, and his behaviour seemed to improve. However, he wasn’t able to make many friends there. He left the school in 1854, and he then attended Leiden University for two years. By then, his parents were officially separated, but they would never divorce.

In 1861, William was introduced to Princess Anne Murat, a granddaughter of Caroline Bonaparte and Joachim Murat, but if a marriage was the intended goal, it never took place. Likewise, Princess Alice, daughter of Queen Victoria, was considered for him. Meanwhile, William joined the army, but it did little to repair the bad reputation he had already built up, and the relationship with his father was famously bad. The city of Paris had stolen William’s heart, and he would spend most his time there. Stories of his escapades there soon made the papers. He was mocked with cartoons and even received the nickname Prince Citron for his notoriously moody behaviour. His mother was soon writing to a friend that she did not expect her son ever to marry. His younger brother Alexander was known to be delicate and was also expected never to marry. Yet, King William did not want to think about the succession, according to Sophie. He was healthy enough and would probably live quite a long time. However, it was becoming a growing problem. King William’s only surviving brother Henry was childless and his elderly uncle Frederick had just two daughters. King William’s sister Sophie’s descendants would lead to a German prince becoming King of the Netherlands, something nobody wanted.

However, young William did have a bride in mind, but she wasn’t quite up to everyone’s standard. Her name was Anna Mathilda – Mattie – Countess of Limburg Stirum. His father would never allow a marriage to a Dutch noblewoman, only a woman of royal blood would do. And so William partied his worries away in Paris while going into huge debts. He would return to the Netherlands just once more, for the funeral of his mother. On 7 January 1879, King William remarried to Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont. Emma would never meet her stepson. In the late spring, the younger William became seriously ill with pneumonia. He died on 11 June 1879 in the arms of his chamberlain; he was still only 38 years old. His position as heir and the title of Prince of Orange passed to his younger brother Alexander. He would die almost five years later to the day, leaving the four-year-old Wilhelmina as the heir.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of William, Prince of Orange appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 9, 2020

Isabel Fernanda of Spain – From first lady of the land to penury

Isabel Fernanda of Spain was born on 18 May 1821 as the daughter of Luisa Carlotta of Naples and Sicily and Infante Francisco de Paula of Spain. Her parents were uncle and niece, and several of her ten siblings would die young. Isabel would be their eldest surviving child.

Isabel Fernanda’s aunt, her mother’s sister, became Queen of Spain as the wife of Ferdinand VII of Spain and would become the mother of Queen Isabella II of Spain. Ferdinand set aside salic law (which barred women from inheriting the throne) in favour of male-preference primogeniture to allow for the succession of his eldest daughter. Following his death in 1833, Isabel Fernanda’s mother supported her niece as Queen, but Luisa Carlotta was deeply disappointed in her sister’s secret remarriage to Agustín Fernando Muñoz. The Queen regent eventually ordered Luisa Carlotta and her family abroad.

They settled in France where they often attended the court of Louis Philippe, King of French, whose wife Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily was Luisa Carlotta’s aunt. At the French court, they were described by the Duchess of Dino. “The Infanta is very fair, with a face which, though washed out, is none the less stern, with a rough manner of speaking. I felt very ill at ease with her, although she was very courteous. Her husband is red-haired and ugly, and the whole tribe of little infantes, boys and girls, are utterly detestable.” When Luisa Carlotta’s sister was ousted from her regency and exiled to France, the family were able to return to Spain.

They were eventually allowed to return to Madrid, and they focussed their attention on marrying their sons Francisco de Asis and Enrique to the young Queen Isabella II and her sister Luisa Fernanda. Their insistence led to a second banishment in 1842. In 1843, Queen Isabella was declared to be of age, and Luisa Carlotta and Fransisco returned to Madrid once more. They moved into the Palace of San Juan.

By then, Isabel Fernanda had done the unthinkable. While being educated at the Sacre Coeur in Paris, she eloped with her riding instructor Count Ignatius Gurowski. The family was initially appaled by the secret marriage, but they were reconciled. They made their home in Brussels while receiving a pension from the Spanish government under Queen Isabella II. However, during Isabella’s exile, this pension was apparently stopped, and they were living in quite reduced circumstances for a while. Isabel Fernanda’s brother married Queen Isabella in 1846 and offered to make the Count a Duke to which he reportedly replied, “I would prefer being an old Count to a new Duke!”1

Though the marriage was initially kept hushed up, her brother’s high profile as the Queen’s consort brought her into the spotlight of the Belgian Court. The couple went on to have eight children together, though only four would survive to adulthood. She was also rumoured to have had an affair with King Leopold I of the Belgians and they reportedly had a daughter together. After the death of Queen Louise, Isabel Fernanda was essentially the first lady of Belgium.

Isabel Fernanda moved to Paris in 1886 where her husband Ignatius would die the following year at the age of 74. Isabel Fernanda survived him for ten years, dying on 8 May 1897 – just days before her 76th birthday. She was reportedly in financial ruin, acting as the hostess of a hotel. She was buried at the famous Pere Lachaise Cemetery where her husband was also buried.

The post Isabel Fernanda of Spain – From first lady of the land to penury appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 8, 2020

Sophie of Greece and Denmark – An exiled Princess (Part two)

As the Second World War began in its earnest, Christoph was often away. He volunteered for active service in September 1939. He was promoted to First Lieutenant on 1 May 1940, followed by a promotion to Captain on 1 September 1940. From January to May, he was stationed at Bad Homburg. He was then transferred to Luxembourg until the end of June where he did mostly staff work. He was awarded the Iron Cross second class as recognition for his work helping to plan the bombing of Rotterdam and Eindhoven. On 21 May, he wrote to Sophie, “We are in a little summer Schloss about 25 km north of Lotti’s (Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg) capital. And soon we will move on towards the West… What do you say to our success? Isn’t it marvellous! I wonder what will happen next?”1 He was then assigned to Belgium before being transferred to Calais. In June 1941, he was transferred to the Eastern front. He wrote to Sophie, “If you should not have any letters for some time, don’t be worried. You can guess the reason.”2 During his time there, he was transferred to a fighting squadron.

He underwent training for active combat and began to prepare for flying missions. By the end of November 1941, he had already done 18 missions over enemy lines. He was recalled from combat later that month as a result of orders prohibiting princes from engaging in combat. He was incensed and went crazy sitting inside all day. Christoph was eventually ordered to Sicily, and he was briefly able to see Sophie on the way there. In December 1942, he was transferred to Tunisia, and he witnessed the gradual defeat of General Rommel. Christoph moved around North Africa for a while before being told to evacuate in May 1943. He was allowed on leave for the month of June, and he took the opportunity to write a will at Kronberg. Little did he know, it would also be the last time he would see Sophie and his children. He left behind a pregnant Sophie at the end of June 1943 and headed back to the front in Sicily. Despite the ban on princes serving in combat, Christoph found his way to a plane.

Circumstances surrounding his death remain mysterious. On 7 October 1943, Christoph and another pilot named Wilhelm Gsteu embarked on a Siebel 204 and around 5.30 p.m. the plane crashed into a mountain near Monte Collino in the Apennine Mountains. Their bodies were not found until two days later. They were eventually buried in a cemetery near Forli. Their true destination and the cause of the crash remain unknown. Sophie and their children were living at Friedrichshof at the time of Christoph’s death. Her grandmother wrote, “Poor dear Tiny (Sophie), she loved her husband & had been so anxious about him ever since he was in Sicily… I am so sorry for Mossie (Princess Margaret of Prussia – his mother) too; this is the 3rd son she has lost in war, the eldest two in the last one & now her favourite in this one.”3

General Siegfried Taubert made an unannounced visit to Sophie in November 1943 to “sniff around” on the orders of Heinrich Himmler. He was “astonished by her terrible appearance; she has become thin and looks to be suffering a great deal, probably because she is expecting her fifth child.”4 On 6 February 1944, she gave birth to a daughter named Clarissa. When her mother visited a few months later, Alice wrote, “I went to Tiny, who is so brave when she with her children and us, being her usual self and making jokes but her hours in her room alone are hardly to be endured… I never suffered ‘the accident’ (Cecilie’s plane crash) as I did those three weeks with Tiny and I certainly will never forget them as long as I live. Her children are perfectly adorable, you would love them, and the new baby is too sweet for words.”5 On 3 December 1944, Sophie’s father Andrew died at Monte Carlo.

On 29 March 1945, the Americans arrived at Friedrichshof, and a few weeks later, the entire family was ordered to leave within four hours. Sophie’s mother-in-law was ill with pneumonia and refused to vacate until a soldier threatened to shoot her. They eventually ended up separated over several homes. In May 1945, Sophie moved to Wolfsgarten where Cecilie’s brother-in-law and his wife lived. They took in several refugees from their family.

In January 1946, Sophie became engaged to Prince George William of Hanover, who became the headmaster of Salem School. He had served in the army as well under the command of General Guderian, and he had fought at Smolensk and Kiev. When Sophie requested to wear some of the Hessian jewels for her wedding, it turned out that they were stolen. Her younger brother Philip attended their wedding on 23 April 1946. The groom’s father, the Duke of Brunswick – as a male-line descendant of George III – applied for formal consent for the marriage under the Royal Marriages Act 1772 to his cousin, King George VI, in 1945. However, Germany and the United Kingdom were still in a state of war, and King George VI was advised not to reply. He privately sent his best wishes, and his mother Queen Mary was happy that Sophie had found a new husband. Sophie and her two surviving sisters were not invited to Prince Philip’s wedding to Princess Elizabeth in 1947 due to the politically sensitive situation. They were able to make private visits to the United Kingdom, and Sophie was the first of Philip’s sisters to visit him in 1948.

Between 1950 and 1953, the estate of her late husband underwent a posthumous identification trial to determine if Sophie and her children were entitled to their shares of the inheritance. If Christoph was placed in Category I or II, his property was subject to seizure by the state. It wasn’t until March 1953 that he would not have been in Category I or II, or even III, and all restrictions on his estate were lifted. Sophie and George William went on to have three children together: Welf Ernst (born 25 January 1947), Georg (born 9 December 1949) and Friederike (born 15 October 1954).

Sophie and her sisters were able to attend the coronation of their sister-in-law, Queen Elizabeth II, at Westminster Abbey. They sat in the royal box behind the Queen Mother with their mother, Alice. In 1964, Sophie was asked to be the godmother of Queen Elizabeth’s youngest son Prince Edward. Prince Philip helped to send some of his nieces and nephews to boarding school. Sophie, in turn, was fond of Prince Charles and she sometimes stayed with him at Highgrove. On 16 October 1969, her sister Theodora died quite suddenly, followed by her mother on 5 December 1969 at Buckingham Palace. Sophie gave her three dressing gowns to the nurses who had cared for her. Sophie and Margarita attended the funeral at St George’s Chapel. Alice was eventually moved to Jerusalem per her own wishes in 1988. By then, Margarita had passed away as well – she had died on 24 April 1981.

She accompanied Prince Philip to Jerusalem in 1994 when their mother was being as recognised as Righteous Among the Nations for hiding a Jewish family. She spent her final years living quietly at Schliersee, near Munich. She was also in regular contact with Princess Margaret of Hesse, the wife of Cecilie’s brother-in-law. In the summer of 2001, she moved to a nursing home where she died on 24 November 2001 at the age of 87. She was survived by her second husband as well as seven of her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She was buried in the Schliersee Cemetery and was joined there by her second husband when he died in 2006.

The post Sophie of Greece and Denmark – An exiled Princess (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 7, 2020

Sophie of Greece and Denmark – An exiled Princess (Part one)

Princess Sophie of Greece and Denmark was born on 26 June 1914 as the fourth daughter of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg. Her grandmother Victoria arrived in early June to be with Alice as she gave birth, but Sophie arrived rather late. Victoria wrote on the day of her birth, “Well, the baby is here at last. She (alas!) made her appearance at 6 a.m. Of course, it is a disappointment her being another girl; she is a fine healthy, large child.”1 Her elder sisters were Margarita, Theodora and Cecilie. Her younger brother is Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

She spent her early years in Greece with her mother and sisters until they were forced to leave for Switzerland in 1917. The family’s main base became the Grand Hotel in Lucerne. In 1920, Sophie, Cecilie and their mother Alice became ill with influenza, but luckily they all recovered. They were briefly allowed back to Greece in 1920, and her younger brother Philip was born there on 10 June 1921. In 1922, Sophie and her sisters were invited to be bridesmaids at the wedding of Edwina Ashley to Alice’s brother Louis (later 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma). At the time, their grandmother described them as, “quite natural and unaffected girls, really children, that do Alice credit, but though nice looking, they have merely the good looks of youth.”2 She added, “Cécile will certainly be the prettiest of the lot, Tiny (Sophie) is great fun & the precious Philipp (sic) the image of Andrea (Andrew)”3

More trouble was to come as King Constantine abdicated for a second time in 1922, now in favour his eldest son George. It was arranged that the King and Queen would leave with Andrew, but he was not with them when they left. Alice and Andrew remained in Corfu with the children for now. Andrew was eventually arrested, leading to much worry. He was banished from Greece, and he gathered the family from Corfu where Alice had hurriedly packed a few belongings. Baby Philip was carried in a cot made from an orange box. Margarita and Theodora were left in the care of their grandmother in England, while Alice took the younger three siblings to Paris into the care of Andrew’s sister-in-law Princess Marie Bonaparte, the wife of Prince George of Greece and Denmark. She loaned the family a house in France where they would eventually live with the entire family. Sophie later wrote, “There were staff of different nationalities. One of the maids came in and said that a footman had attacked her with a knife. There were always problems paying the bills.”4

While at St Cloud, Andrew often took the younger children on trips to Paris or for walks in the Boulogne woods. They also had a tennis court, and there was a big family lunch every Sunday. In 1923, the four girls once again acted as bridesmaids, this time for the wedding of Lady Louise Mountbatten to the future King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden. In the summer of 1926, Cecilie and Sophie spent time at Kensington Palace. Even though Sophie was the youngest of the four sisters, she would be the first to marry; her future husband was Prince Christoph of Hesse.

Cecilie was busy preparing both her and Sophie’s trousseau in Paris. She wrote to their mother, “Tiny’s clothes are nearly ready. I saw her trying them on the other day. They are lovely, and her wedding dress is too beautiful for words. Satin and quite simple with a lace and tulle veil. They have not started mine yet.”5 On 15 December 1930, Sophie was helped into her dress by Theodora, Cecilie and Philip at Friedrichshof. She was loaned the Empress Frederick’s Diamond tiara by her father-in-law. A Greek Orthodox priest conducted the Orthodox wedding ceremony in the drawing-room at Friedrichshof, and Philip carried her train. A Protestant service was held in the church at Kronberg. Louise later wrote, “Tiny was like a child at a party in her own enjoyment & excitement over her wedding.”6 Cecilie married Georg Donatus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Hesse on 2 February 1931. Margarita was next to marry. On 20 April 1931, she married Gottfried, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. Theodora was now the last of the sisters left unmarried. In June, her engagement to Berthold, Margrave of Baden, was announced. They were married on 17 August 1931 at the Neues Schloß in Baden-Baden.

In October 1931, Christoph applied to join the Nazi Party but only a second application in the spring of 1933 made it official. He received the membership card number 1,498,608 on 3 July 1933, which was later backdated to 1 March. As it was more prestigious to have joined before 1933, his number was later revised to 363,176. Sophie would eventually join the Nazis’ women’s auxiliary (NS-Frauenschaft) in 1938. Christoph entered the SS in February 1932 with much enthusiasm. He wrote to his mother, “We are all terribly excited about the elections. I do hope they will bring the beginning of change which we are all longing for so much.”7 When Sophie celebrated her 18th birthday in 1932, she wrote, “I spent a very happy [birth] day on Sunday, although Chri was unexpectedly called away on duty this morning.”8 After the Nazis seized power in 1933, her husband’s career really took off. They had access to the highest ranks of the Nazi party, and they were both enthusiastic. On 10 April 1935, Sophie attended the wedding of Emmy Sonnemann and Hermann Göring, one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party.

On 10 January 1933, Sophie gave birth to her first child – a daughter named Christina Margarethe. Another daughter named Dorothea was born on 24 July 1934, followed by a son named Karl on 26 March 1937 and another son named Rainer on 18 November 1939. Shortly before the birth of Rainer, Christoph reported to the Luftwaffe, and he wrote to Sophie, “How I miss you here and long for you. It is simply terrible. I am so depressed and so miserable that I shall be pleased to get away from this house in which we have spent those lovely happy years together and enjoyed having our little Poonsies (their children). Oh, darling if only you were here! When I enter the house I think how often the door used to open like with magic and then you angel were there waiting for me smiling or laughing and giving me a thrill of happiness I feel a lump in my throat to think of it. I love you, love you, love you, my angel, and you mean everything to me… Lovingly as your old adoring Peech [Christoph]9

Tragedy struck in November 1937 when Sophie’s sister Cecilie was killed alongside her family in an aeroplane crash. The funeral took place on 23 November, and Sophie attended the funeral with her husband. He wore his SS-uniform as crowds saluted the procession with the Heil Hitler greeting.

Part two coming soon.

The post Sophie of Greece and Denmark – An exiled Princess (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 6, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Train accident at Houten

On 7 June 1917, Queen Wilhelmina was travelling from Den Bosch to The Hague, and her two royal coaches were attached to the back a regular train service. She was in her saloon car when eleven of the coaches derailed, and one even rolled off the embankment. The train had broken up in parts, with the front part remaining standing.

Fortunately, the royal coaches remained standing as well, though they did come off the rails. Queen Wilhelmina remained unharmed, but the damage was enormous. Queen Wilhelmina helped to care for the 26 wounded with the aid of a British man. No one was killed in the accident, which seems like a miracle if you look at the photos. The only related death appears to have been the stillbirth of a baby later that day of a heavily pregnant woman who had been on the train. The cause of the derailment was probably the expansion of the tracks due to the heat.

A railway worker reported, “I soon saw the entire train off the rails. Because we came from behind, we reached the royal carriages first. Just then, the Queen alighted. Exactly, sir, like nothing had happened. To a lady of her entourage, she yelled, “Fetch my first-aid kit and the bottle of Eau de Cologne next to it”. With a crowbar, I opened the door of the following carriages. My buddy and I were the first to get a splash of Eau de Cologne on our dirty handkerchiefs and then the Queen went to work.” Queen Wilhelmina used the Eau de Cologne on a woman who had lost consciousness.1

Queen Wilhelmina boarded the front part of the train with several other passengers, and they were brought to Utrecht. The Queen was praised for her calm appearance and bravery.

Congratulations on her survival soon began pouring in, and various royal palaces had registers where people could congratulate her.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Train accident at Houten appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 5, 2020

Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily – A Crown of Thorns (Part three)

The exiled King and his family slowly made their way to England as Maria Amalia, and her husband reluctantly stepped into their new role. Her husband continued to claim that he only accepted the crown to save the country from anarchy, but it took quite some time before affairs were actually settled. The city was restless, and the family eventually settled in the Tuileries where her husband had a moat dug under their windows, saying, “I do not intend my wife’s ears to be polluted with the horrors Marie Antoinette had to endure when the people had the entrance to the gardens and could come close to the windows.”1 Throughout, Maria Amalia was praised for her courage.

The greatest joy of her life was her family, and they soon settled into a routine. Her two eldest sons entered the army, while the third entered the navy. Her second son was also offered the Crown of Belgium, but he declined, and it eventually went to Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha who would marry her eldest daughter Louise in 1832. Maria Amalia’s routine consisted of her rising early, doing her toilette, and opening her correspondence. She would then hear mass and have breakfast with her family. She would then sit and work with her daughters, and eventually daughters-in-law, on embroidery until noon. She then held audiences before continuing to work with her secretaries on petitions and charitable works. At one point, she gave away 400,000 francs of her private income of 500,000 francs to charity.

The next few years saw her children get married and have children of their own. Her eldest son married Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1837, and they had two sons together. Louise married the King of the Belgians in 1832, and they had four children together. Marie married Duke Alexander of Württemberg in 1837, and they had one son together. Louis married Victoria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1840, and they had four children together. Clémentine married August of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1843, and they had five children together. François married Francisca of Brazil in 1843, and they had three children together. Charles died at the age of eight in 1828. Henri married Maria Carolina of the Two Sicilies in 1844, and they had seven children (though only two would live to adulthood). And lastly, Antoine married Luisa Fernanda of Spain in 1846, and they had ten children together (though not all lived to adulthood).

Maria Amalia loved visiting Louise in Brussels and was present for the birth of her first grandson in 1833, but tragically the Prince would die young. Another tragedy came in 1839 when Maria Amalia’s daughter Marie died suddenly. Her last words were reported back to her mother, “Tell Mamma how much I love her, and that I am glad she is not here to be grieved by my sufferings.”2 She was still only 25 years old. In 1842, Maria Amalia’s eldest son Ferdinand was killed in an accident. His horses were startled, and he jumped from his carriage but hit his head and never regained consciousness. The family hurried to be with him and sat around him in prayer when he died. He left two young sons behind. As Maria Amalia’s husband was by then 69 years old and his heir now just four years old, fears of a revolution began to loom. It was said that after her son’s death, Maria Amalia’s hair began to turn white.

During these years, she became more and more religious, spending long hours at prayer. In 1843, the family was visited by Queen Victoria, and while Maria Amalia’s husband made a return visit the following year, she did not join him. In January 1848, Maria Amalia’s beloved sister-in-law Adélaïde, who had lived with them for so long, died. She had been a valuable advisor to her brother. It was to be a bad year all around. Another wave of revolutions rocked Europe in February and on 24 February 1848, Maria Amalia’s husband abdicated in favour of his nine-year-old grandson. They were then escorted by the National Guard to waiting carriages which would bring them to St. Cloud. Her husband wanted to wait out the insurrection to see if his abdication put an end to it, but it soon became apparent that his young grandson was not accepted and that France had declared itself a republic. Maria Amalia resigned herself to the situation, and the family decided to split up to avoid attracting more attention. Maria Amalia and her husband went to Honfleur to await a chance to go to England. She dressed in the plainest clothes she could find. Several sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren would try to take a different route to England. After a harrowing journey, they arrived at Newhaven.

Queen Victoria decided to place Claremont at their disposal as a residence. Queen Victoria later wrote, “They both look very dejected, and the poor Queen cried much in thinking of what she had gone through, and what dangers the King had incurred; in short, humbled, poor people they looked.”3 Luckily, their family also eventually made their way to Claremont. Their property was ultimately restored to them, so they had an income. Maria Amalia’s husband only survived his abdication for two years, and he died at Claremont on 26 August 1850. She would survive him for 16 years but would not be lonely as she was surrounded by her children and grandchildren.

As she grew older, she was unable to leave the house during the winter. By January 1866, her health visibly began to fail her. She still went on a drive on 18 March but remained in her bedroom the following day. Over the next few days, she was hardly able to stay awake, and the family began to gather around her. She was able to press their hands but could not speak to them. A priest recited the prayers for the dying and administered extreme unction. She died on 24 March 1866 at the age of 83. Her son Louis wrote, “The Queen is no more. We have lost that dear mother, who was referenced as a kind of Divinity in our family. It is a great blow to all of us, but we have the consolation of knowing that the sorrows and trials of her life are at last over, and that she has entered into the enjoyment of the eternal happiness which her great virtues must have won for her, and that she passed away without pain.”4

Her coffin remained in the chapel of the cemetery at Weybridge beside that of her husband until they were moved to the family chapel at Dreux in 1878.

The post Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily – A Crown of Thorns (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 4, 2020

Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily – A Crown of Thorns (Part two)

King Louis XVIII was quite fond of Maria Amalia, and he wrote of her, “I had heard a great deal in favour of this Princess, but when I became personally acquainted with her, I found in her many more good qualities than I had been to led to expect. Such a wife in some degree quieted my apprehension as to the Duc d’Orléans.”1 The Orléans family paid their respects to the King the day after they arrived in Paris. Maria Amalia was also introduced to Madame Royale – the daughter of Marie-Antoinette – who was married to the King’s nephew, the Duke of Angoulême. They became fond of each other, and Madame Royale wrote of her cousin, “She is so good, so excellent, so closely related to us.”2

At the Palais Royal in Paris, Maria Amalia gave birth to her second son on 25 October 1814 – he was named Louis, Duke of Nemours. Napoleon’s brief return after his escape from Elba saw the family flee to England. They first lived at the Star and Garter Hotel in Richmond, before moving to a house later known as Orléans House at Twickenham. She became acquainted with Princess Charlotte of Wales who lived at Claremont and Frederica Charlotte of Prussia, Duchess of York, who lived at Oatlands. Maria Amalia gave birth to a daughter named Françoise at Orléans House on 26 March 1816, but she died on 20 May 1818. King Louis XVIII was returned to his throne after Napoleon’s final defeat, but they were not permitted to return until 1817. They returned to the Palais Royal on 15 April 1817, just a month after Maria Amalia had given birth to another daughter named Clémentine on 6 March.

While Madame Royale and the Duke of Angoulême would have no children, the Duke’s brother the Duke of Berry was expected to provide an heir to the throne. In 1816, he would marry Maria Amalia’s niece Maria Carolina. They went on to have one surviving daughter, and in 1820, the recently widowed Maria Carolina gave birth to the Duke of Berry’s posthumous son, securing the succession for another generation. Maria Amalia gave birth to a third son – named François, Prince of Joinville – in 1818 and a fourth son – named Charles, Duke of Penthièvre – in 1820. A fifth son – named Henri, Duke of Aumale – was born in 1822, followed by her sixth son and final child – named Antoine, Duke of Montpensier – in 1824. The family began to spend a lot of time at their country house at Neuilly.

On 16 September 1824, Maria Amalia and her husband were present at the deathbed of King Louis XVIII. He was succeeded by his brother the Count of Artois, now King Charles X. They attended the new King’s coronation, and Maria Amalia wrote to her son Louis, “We have just returned from the ceremony of consecration. It lasted three hours. There was some confusion, no one knew what to do. The entrance of the knights in procession was very grand. Papa was superb and looked like Louis XIV.”3 The new King raised the entire Orléans family to the style of “Royal Highness” which had previously only be accorded to Maria Amalia, as the daughter of a King. Her husband was currently third in the line of succession behind the Duke of Angoulême, now known as the Dauphin, and the young son of the Duke of Berry.

In 1825, Maria Amalia was finally able to see the one sister she had left again – all her other sisters had already passed away. She, her husband and their three eldest children went to see the King and Queen of Sardinia at Chambery. The years between 1825 and 1830 were ones of domestic bliss for Maria Amalia. However, by 1830 her husband was out of favour with the King. They were also standing on the edge of another revolution. Soon, the Liberal Constitutional Party, which had an immense majority, looked towards Maria Amalia’s husband as the solution. Maria Amalia spent a lot of time in prayer. The children were sent away to Villiers Coterets while Maria Amalia and her sister-in-law remained behind at Neuilly. While her sister-in-law was in favour of the Duke taking the crown, Maria Amalia was adamant that he was an honest man and would do nothing against the King. The King eventually abdicated in favour of the Duke of Berry’s 9-year-old son and appointed Maria Amalia’s husband as Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom and regent. His son the Dauphin also signed the document 20 minutes later.

However, Maria Amalia’s husband eventually accepted the crown for himself after he agreed to accept a constitution. Maria Amalia was horrified, and she sobbed, “What a catastrophe. They will call my husband a usurper!”4 She and her children eventually travelled to Paris, though people commented on her drawn face and her red eyes. In August 1830, her husband was declared, “King of the French by the Will of the People”, rather than “King of France by the Grace of God.” Maria Amalia did not have an official declaration as Queen of the French, but she was thereafter referred to as Queen. She later said, “Since by God’s will this Crown of Thorns has been placed on our heads, we must accept it and the duties it entails.”5

Part three coming soon.

The post Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily – A Crown of Thorns (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 3, 2020

Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily – A Crown of Thorns (Part one)

Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily was born on 26 April 1782 as the daughter of Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies and Maria Carolina of Austria. She was their tenth child out of a total of 18. Her mother was a sister of Queen Marie Antoinette of France, Maria Christina, Duchess of Teschen, Archduke Maximilian Francis, Maria Anna of Austria, the shortlived Maria Carolina of Austria, Maria Elisabeth of Austria, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, Maria Josepha of Austria, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, Maria Amalia, Duchess of Parma, Maria Elisabeth of Austria, Maria Johanna of Austria, Charles Joseph of Austria. She was thus a granddaughter of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria.

Maria Amalia was born at the Caserta Palace, just outside Naples, and it is here that she would pass her early years. She learned to read at an early age and was entrusted to the care of a governess named Donna Vicenza Rizzi. When she was old enough, she often went hunting with her father, and she would grow up to be an excellent horsewoman. At a young age, Maria Amalia was betrothed to her cousin Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France, but he would die in 1789. The following French Revolution and the execution of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette put an end to any French match. Around this time, Maria Amalia also made her first communion and solemn prayers were said for her murdered aunt and uncle; Maria Amalia was profoundly touched. She began to focus more on her studies and her religion.

In 1790, Maria Amalia joined her entire family for a trip to Vienna for the betrothal of her younger brother, the future Francis I of the Two Sicilies, to Maria Clementina of Austria and for the marriage of her two eldest sisters Maria Theresa and Luisa Maria to the future Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor and his brother the future Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany respectively. From 1800 until 1802, Maria Amalia, her mother and several siblings lived in Austria where her mother searched for suitable matches for her daughters. Her younger sister Maria Antonia married the future Ferdinand VII of Spain in 1802, but she would tragically die of tuberculosis in 1806. Maria Amalia had been considered for the future King as well, but her sister had been closer to him in age. Maria Amalia missed her sister terribly when she left to be married.

In 1802, the family returned to Naples, but in 1806, Napoleon decided to annex Naples. The family fled to Sicily, but some of their furniture was lost on the way, and they were perpetually short of money. Her elder sister Maria Cristina married the future King Charles Felix of Sardinia in 1807, leaving Maria Amalia as the only unmarried daughter. Napoleon proposed a match for her with his stepson Eugène de Beauharnais, but it was promptly rejected. As her mother’s eyesight began to fail her, Maria Amalia spent her days reading and writing for her. She would remember this time with her mother fondly.

In 1808, Maria Amalia’s future husband arrived in Sicily. He was Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, the son of Philippe Égalité, who had voted for the death of the King of France and Maria Amalia’s aunt Marie Antoinette. Her mother was scared to meet him, but upon their meeting, she said, “I ought to detest you, and yet I feel a liking for you.”1 Maria Amalia wrote of their first meeting, “He is of middle height, inclined to be stout; he is neither handsome nor ugly. He has the features of the House of Bourbon and is very polite and well educated.”2 The wedding contract was signed on 15 November 1809 but the wedding itself had to be postponed when her father broke his leg. The wedding eventually took place on 25 November in the room of her father so that he could attend. Her wedding dress was of cloth of silver, and she wore a diamond tiara and white feathers in her hair. She later wrote in her journal, “Knowing the sacredness of the tie I was about to form, I was filled with emotion, and my limbs tottered under me, but the Duke of Orléans pronounced his ‘Yes’ in such a resolute voice that it gave me courage.”3 They then went downstairs to the chapel for a Te Deum service and for the Service of Benediction. Afterwards, the newlyweds showed themselves to the people from the balcony.

Her father had given them a residence called the Palazzo d’Orléans but while it remained under repair, they stayed at the Royal Palace. Her husband’s sister Adélaïde came to live with them, and she and Maria Amalia became close friends. She wrote about her new sister-in-law in her journal, “She seems very amiable and witty, and pleases me greatly.”4 The Palazzo would eventually become a meeting place for intellectuals. The following year, Maria Amalia gave birth to her first child, a son named Ferdinand, the future Duke of Orléans. Two daughters, Louise and Marie, followed in 1812 and 1813.

The fall of Napoleon restored King Louis XVIII – brother to the ill-fated King Louis XVI – to the French throne, and Louis Philippe was received kindly and restored to his old rank in the French army. He was also given all the estates the Orléans family had previously possessed. In July 1813, he went to fetch Maria Amalia and his family.

Part two coming soon.

The post Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily – A Crown of Thorns (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 2, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of Sophie of Württemberg

Although Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands obviously never knew her father’s first wife, Sophie’s death opened up the possibility of his remarriage and the eventual birth of Wilhelmina.

Sophie of Württemberg was born in Stuttgart on 17 June 1818 as the daughter of King William I of Württemberg and his second wife Catherine Pavlovna of Russia. She married her first cousin William, future Prince of Orange and future King William III of the Netherlands in Stuttgart on 18 June 1839. She considered herself to be more intelligent than him and thought she could dominate him. She became Princess of Orange upon the abdication of King William I of the Netherlands in 1840. Sophie and her husband William never got along. The births of their sons changed nothing. They had three sons, William in 1840, Maurice in 1843 and Alexander in 1851.

Sophie became Queen consort in 1849 when King William II died suddenly. By then, William and Sophie were on the brink of a separation. Their second son Maurice suffered from meningitis, and they quarrelled by his sickbed. Sophie wanted to consult another doctor, but William refused. Maurice ultimately died of the illness. In 1855, they separated for good, but divorcing was not an option. William was given custody of their eldest son and Sophie was allowed to keep their youngest son Alexander until he was nine years old. Sophie would also have to continue to fulfil her duties as Queen.

From 1855, she lived mostly in Huis ten Bosch, and she went to visit her father almost every year. She was also a regular visitor to Emperor Napoleon III and his wife, Eugénie. She corresponded with intellectuals, who praised her. Historian John Lothrop Motley wrote, “The best compliment I can pay her is, that one quite forgets that she is a queen, and only feels the presence of an intelligent and very attractive woman.”

Sophie’s health deteriorated in early 1876. On 7 January 1876, she had arrived in Paris while already ill, and she had to be carried to her apartments. She continued her travels towards to Cannes, where she hoped to feel better. Her doctors reported that she suffered from ‘fièvre paludiène’ (malaria), tiredness, tightness in her chest, and coughing attacks. These reports were published in the newspapers. William thought the entire reporting on her health was ridiculous and believed she only wanted the attention. When she felt a little better, she wrote, “The King cannot forgive me that I didn’t die, as he had expected. He never comes to me, never asks how I am. When I was so very ill last time, he sang and had someone loudly play the piano under my bedroom.”1

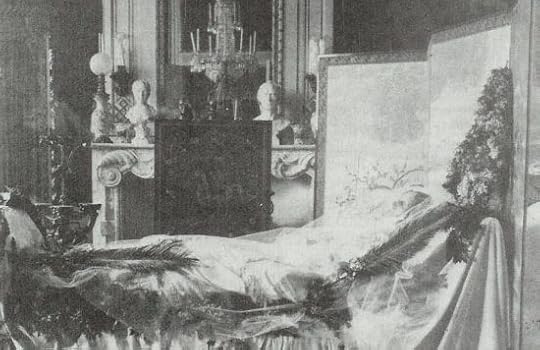

Sophie would not recover from her next illness. During the spring of 1877, it became clear that the end was near. On 2 June 1877, one newspaper reported, “From The Hague, we received, this morning at 11, the sad message that Her Majesty The Queen is dying.”2 This time, her husband did bother to go to her at Huis ten Bosch.

Sophie died on 3 June 1877 just before noon, and the following autopsy showed that her bowels, gallbladder, liver and lungs had all been infected. It had been a miracle that she lived as long as she did. Newspapers report, “The entire Netherlands mourns the death of their beloved Queen.” On her deathbed, she wore her wedding veil, believing that she had died the day of her wedding.

(public domain)

(public domain)Sophie, Queen of the Netherlands, was buried on 20 June in the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft. King William, their two sons and Prince Henry and Prince Frederick were all there. William stayed in the church while the others went down into the crypt.

The palace of Huis ten Bosch was immediately closed after Sophie’s death and it stood empty for a long time. Her husband remained in The Hague until 29 June when he left for Paris with a certain Mademoiselle Ambre.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The death of Sophie of Württemberg appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 1, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Juliana departs for Canada

The Netherlands had been neutral during the First World War, but the German invasion on 10 May 1940 changed everything. Juliana and her two daughters had been sleeping in a shelter by Huis ten Bosch, and Wilhelmina ordered her heir to leave the country. The initial plan was for her and her daughters to go to Paris, but that was soon no longer an option. England was plan B.

In the early morning of 10 May, Queen Wilhelmina issued a proclamation protesting the attack on the Netherlands and the violation of the neutrality. Huis ten Bosch, with its rural setting, was considered to be too vulnerable to an attack and so Wilhelmina moved to Noordeinde Palace, which is located in the centre of The Hague. They would spend the nights in a shelter in the gardens of Noordeinde Palace. On 12 May, Juliana and her family finally managed to board a British ship. The goodbye between mother and daughter was difficult. Bernhard accompanied his wife and daughters to England, but he was also an officer in the army and felt that he should be staying. Bernhard immediately returned to the Netherlands when Juliana was safely in London.

Queen Wilhelmina had been told by her cabinet that she should be leaving the country as well. In the early hours of 13 May, Wilhelmina received a visit from General Winkelman, who told her that the situation was dire. Wilhelmina spoke on the phone with King George VI of the United Kingdom before bursting into tears in the shelter. There was no other option left – she would need to go as soon as possible. Wilhelmina boarded the HMS Hereward at Hook of Holland and initially wanted to travel to the province of Zeeland. This turned out to be impossible, and the HMS Hereward set sail for England.

While Queen Wilhelmina set up a government in exile in London, it was decided that Juliana and her daughters should go to Canada for their safety. Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, Wilhelmina’s first cousin and her husband, who was the Governor-General of Canada, had offered to help. After all, England could be invaded as well. On 2 June 1940, Juliana, her daughters and several others boarded the HNLMS Sumatra, which was accompanied by the HNLMS Jacob van Heemskerck. Juliana’s husband Bernhard waved her off from Milford Haven while Queen Wilhelmina bade her daughter farewell from Lydney Park. Wilhelmina later wrote in her memoirs, “I gazed after the car as it drove off from Lydney Park – when and where would we meet again? Bernhard returned late in the evening, very unhappy at the prospect of their long separation. Several weeks passed before Juliana’s first letter brought a ray of light for him and myself.”1They arrived safely on 10 June 1940 and stayed at Government House at first. A month and a half later, they moved to a villa in Ottowa.

Juliana often wrote to her mother and her husband in England. It would be a long time before she would see them again. Wilhelmina wrote to her daughter, “Your letters are my lungs that will allow me to breathe to continue to live and work.”2 Juliana was kept informed of state business, she would need to be able to take over if it ever came to it after all. Their letters went by diplomatic post.

They would not meet again until June 1942. Wilhelmina wrote, “Our happiness at seeing each other again was indescribable. How I enjoyed Juliana’s charming house in Rockliffe Park, in the middle of the woods overlooking a little lake.”3 Bernhard also visited Canada several times. At the end of 1942, Juliana moved to Stornoway, which was a little bigger. By then, she was expecting her third child – Princess Margriet. Juliana also visited the United States several times and met with President Roosevelt, who was quite proud of his Dutch roots. During his inauguration in 1933, he swore the presidential oath on his Dutch family bible.

Juliana was concerned with the life her husband led in England and he hardly ever wrote to her about it. It will come as no surprise that he had an affair, and even though he never mentioned her by name, it is likely to be Ann, Lady Orr-Lewis, the wife of Sir Duncan Orr-Lewis. Bernhard later confirmed in an interview that Juliana knew about it and after the war, Ann sometimes went skiing with the entire family. After the war, he would father two daughters with two different women, and he later acknowledged them.

Juliana left Canada for England in September 1944, but there was little she could do there. In March 1945, Queen Wilhelmina made her first visit to the partially-liberated Netherlands. Juliana would have to wait a little bit longer. In June 1945, she travelled to the United States with 15,000 American troops, and she was deeply touched by their reception in New York.

On 2 August 1945, Juliana and her three daughters landed at Teuge Airport near Arnhem. The years of exile were over.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Juliana departs for Canada appeared first on History of Royal Women.