Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 181

May 3, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – A second tragedy

When Queen Wilhelmina fell ill with typhoid fever in the middle of April 1902, she was about five months pregnant. It was her second pregnancy, but the first had ended in a miscarriage.

For several days, fever ravished the Queen’s body, and it wasn’t until 29 April that the newspapers reported that her condition was improving. To everyone’s great joy, she had survived, but her pregnancy had not remained unaffected. A gynaecologist had been called in, despite the original doctor having realised that the situation was hopeless. Queen Wilhelmina was in quite a bit of pain, and her husband Prince Henry left the room because he could not bear it anymore. He later wrote, “Poor Wimmy suffers a lot; the entire house suffers with her.”1 At 10.30 P.M. on 4 May 1902, Wilhelmina gave birth to a stillborn son. The doctors assured her that it was the typhoid fever that had caused the stillbirth and that she would still be able to have a healthy child. Wilhelmina bravely told the doctor, “It is terribly sad, but I shall bear it.”2 He later wrote, “At that moment I admired our Queen as a woman with an indescribable power of mind, as a heroine to be pitied. I had a new regard for her that will remain until the day I die.”

This time, her recovery was a lot slower. She was deeply saddened to have lost another pregnancy. Prince Henry wrote how it was a double tragedy since the child was a boy. Wilhelmina went on an extended trip to her uncle in Schaumburg, but it failed to cheer her. She later wrote, “I cannot tell you how much I have gone through; I had never known a great sadness, and this was very great.”3 From Schaumburg, she wrote to her former governess Miss Winter, “I knew all the time I was ill that my mother and others kept sending you news and I knew that your thoughts were with me. My sorrow and grief is greater than words can say, I trust to God that He may help me to be brave; you see I have a very dear husband to live for and the idea of being spared for him and thus still able to go through this world with him and be useful to him, will be the greatest help to face life with courage.”4

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – A second tragedy appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 2, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Juliana: Queen-in-waiting (Part three)

On 10 July 1936, the dashing Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld proposed to Princess Juliana and after some consideration, she accepted him. The engagement was meant to remain a secret for three months, but the news leaked, and so it was officially announced on 8 September. Bernhard endeared himself to the public by attempting to speak Dutch at the announcement, making the resistance against a German prince a little less. Their wedding took place on 7 January 1937 – also the wedding anniversary of King William III and Queen Emma. Their honeymoon took them all over Europe and ended in Paris, where Bernhard and his “aunt” Allene completely made over the previously rather dowdy Juliana. Allene had also brought Juliana a dietician who had helped her lose some weight and Juliana had gotten a new haircut. Wilhelmina almost didn’t recognise her.

Juliana in 1937 (public domain)

Juliana in 1937 (public domain)After their honeymoon, Bernhard and Juliana moved into Soestdijk Palace which they renovated to their taste. Juliana’s first pregnancy was announced on 15 June 1937. Juliana was still only two months pregnant when she made the announcement herself via radio. On 31 January 1938, the future Queen Beatrix was born. It had not been an easy labour, but Juliana recovered well, and the baby was healthy. Despite now having a new baby, Bernhard spent most of the time away from his family. On 5 August 1939, Juliana gave birth to a second daughter – named Irene.

In May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands. Juliana and her two daughters had been sleeping in a shelter by Huis ten Bosch and Wilhelmina ordered her heir to leave the country. The initial plan was for her and her daughters to go to Paris, but that was soon no longer an option. England was plan B. On 12 May, they finally managed to board a British ship. The goodbye between mother and daughter was difficult. Bernhard accompanied his wife and daughters to England but he was an officer in the army and felt that he should be staying. Bernhard immediately returned to the Netherlands when Juliana was safely in London. The Netherlands capitulated on 15 May, and he was forced to return to England. Meanwhile, Wilhelmina had been forced to leave as well. At London Liverpool station, Bernhard and King George VI awaited her.

Wilhelmina believed her daughter and granddaughters would be safer in Canada. On 2 June 1940, they boarded the Sumatra. On 17 June, she spoke on the radio, “Please do not regard me as too much of a stranger now that I have set foot on these shores which my own ancestors helped to discover, to explore and to settle. […] Whatever you do, do not give me your pity. No woman evert felt as proud as I do today of the marvellous heritage of my own people… Pity is for the weak, and our terrible fate has made us stronger than ever before. But if you want to show us in some way that we are welcome among you, let me ask you one favour. Give us that which we ourselves shall give unto you from our most grateful hearts – give us that which just now we need more than anything else. You people of Canada and the United States, please give us your strengthening love.”1

CCO via Wikimedia Commons

CCO via Wikimedia CommonsDespite the circumstances, Juliana felt at home in Canada, and she even had a relative there in the form of Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone. She had a freedom there she had not known before. She could go out and about without being recognised and was able to go to the movies and the public pool. Although Bernhard had remained in England, he visited her from time to time. She became pregnant again in 1941 but suffered a miscarriage in September. She was again pregnant the following year, which resulted in the birth of Princess Margriet on 19 January 1943.

On 2 August 1945, Juliana and her daughters returned to the Netherlands – a country ravished by war. Juliana resumed her position as President of the Red Cross, wanting to be useful. However, there would soon be a more important task waiting for her. Wilhelmina’s health had been declining, and she wanted to abdicate. Before that, Juliana would act as regent twice. From 14 October 1947 until 1 December and again from 12 May 1948 until 30 August 1948. Just before the regencies, Juliana gave birth to her fourth and final child, a daughter named Maria Christina (first known as Marijke, later as Christina). Tragically, she was born nearly blind after Juliana contracted rubella while pregnant. This would lead to the introduction of a faith healer at court, who would nearly bring down the monarchy.

Queen Wilhelmina abdicated in her daughter’s favour on 4 September 1948 at the Royal Palace in Amsterdam. At noon, the balcony doors of the palace swung open, and Wilhelmina presented Juliana to the public as the new Queen with visible emotion. She shouted, “Long live our Queen!” Wilhelmina reverted back to the style and title of Her Royal Highness Princess Wilhelmina.

Two days later, on 6 September, Queen Juliana was inaugurated at the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. Before taking the oath, Juliana spoke the now-famous words, “Who am I that I get to do this?”2

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Juliana: Queen-in-waiting (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 1, 2020

Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden visits great-grandmother’s grave

According to the official Instagram page of the Swedish Royal House, Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden and her family, and her aunt Princess Christina visited the grave of Princess Margaret of Connaught, Crown Princess of Sweden, yesterday on the 100th anniversary of her death.

Photo: Kungl. Hovstaterna

Photo: Kungl. HovstaternaThe posted photo shows they placed a pot of daisies by the grave as the Crown Princess was nicknamed Daisy in the family.

Princess Margaret of Connaught was the first wife of King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden, but she died 30 years before her husband became King. In the late 1919s, it was announced that Margaret, now 37, was expecting her sixth child, but few knew about the Crown Princess’s declining health. A couple of months earlier, she had been diagnosed with otitis and had to undergo surgery in December. In March the following year, she became ill with chickenpox and was fighting a severe cold. On 30 April, she complained about pain in her right ear and jaw, and the following morning, she suffered blood poisoning and heart failure.

She died on 1 May 1920 – still only 38 years old.

The post Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden visits great-grandmother’s grave appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Wilhelmina returns home from exile

Queen Wilhelmina had been forced to flee after the German invasion in 1940, and she spent most of her time in exile in England with her government. By March 1945 – the war was still going on in the northern parts of the country – Wilhelmina wanted nothing more than to return home. During a 10-day-visit royal visit organised like a military operation dubbed “Nightshade”, Queen Wilhelmina returned home for the first time.

On 13 March 1945, Queen Wilhelmina stepped over a border-crossing marker made of flour at Eede in the south of the Netherlands. She had been brought there by a United States army vehicle with a single piece of luggage and a man named Baud, Princess Juliana’s former secretary who had been held hostage during the war. She travelled to Breda where she moved into a house called Anneville.

By Willem van de Poll / Anefo – Nationaal Archief, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl via Wikimedia Commons

By Willem van de Poll / Anefo – Nationaal Archief, CC BY-SA 3.0 nl via Wikimedia CommonsOn 18 March, she attended a service in the Great Church of Breda. From Anneville, she visited Tilburg, Eindhoven, Den Bosch and Maastricht. On 22 March, she fled back from Venlo to England. She had spent ten days in her beloved country, but it had not been wholly liberated yet. She wrote to the British King George VI that it was, “a most moving and touching occasion which I shall never forget.”1

She could finally return home for good on 2 May 1945, three days before the peace was officially declared. She was joined by her daughter Juliana, and the two landed at Gilze-Rijen Airport.

Wilhelmina returned to the Annevillehouse, and in the evening of 5 May 1945, she spoke on the radio again. “Men and women of the Netherlands. Our language has no words for what is now in our hearts in these hours of the liberation of the entire Netherlands. At last, we are the masters of our own homes and castles. The enemy is defeated, from east to west and from north to south. Gone is the firing squad, the prison and the torture camp.”2

In England, Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, wrote to Queen Mary, “What a woman and yet so clever with her Government.”3

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Wilhelmina returns home from exile appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 30, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelma – The Youth of Princess Juliana (Part two)

After the birth of Princess Juliana, Queen Wilhelmina would suffer two further miscarriages. Juliana would remain their only child and thus heiress to the throne. Juliana spent her childhood between three royal palaces: The Loo Palace in Apeldoorn, Noordeinde Palace and Huis ten Bosch in The Hague. A small classroom with three carefully selected students was formed at Noordeinde Palace so that she would receive her primary education with children her own age.

Wilhelmina loved showing off the young Princess during meetings with her ministers at the palace. In 1911, she wrote, “Our daughter grows like cabbage (fast) and is a lively, mobile, talkative child that notices, copies and asks endless questions.”1 Wilhelmina wanted, above all, to prevent the isolated childhood that she had had. Although Juliana would have a relatively happy family life, her parents drifted apart during the First World War. Henry was a loving father; he enjoyed playing games with her.

The war years would be a difficult time for all of them. Henry, a German prince by birth, was torn in his loyalties and as President of the Red Cross, he was away a lot. The Netherlands was neutral during the First World War, but Wilhelmina still conferred with her ministers nearly every day. At the end of the war, Henry, Wilhelmina and little Juliana were driven around the Malieveld in The Hague in a carriage in celebration. Around them, several monarchies had fallen, but the Netherlands still stood firm. Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany had fled to the Netherlands in early November, something Wilhelmina could not understand. Nevertheless, he would live out his days in the Netherlands. Henry and Juliana visited him and his second wife Hermine sometimes, though her mother never did.

(public domain)

(public domain)During her youth, Juliana was raised by governesses and nurses. She loved animals and liked to play dress up like any other child. One particular dress-up party was immortalised in a painting with her father, mother and Juliana herself dressed in 17th-century dress. Juliana had to pose for nine hours, which she hated.

Juliana’s education as heir the throne would continue at a relentless pace. She would need to be ready to assume the throne at the age of 18 if it was necessary. At the age of 11, her primary education in the classroom ended. After this, she received a private education with several teachers. It was a lonely time for the young Princess, who desperately wanted siblings.

She was delighted to be allowed to attend university after her 18th birthday. Two days after her 18th birthday, her mother installed her in the Council of State and would from now on she attended the Speech from the Throne in the Hall of Knights. She also received an allowance of 200,000 guilders a year, her own household and her own palace at Kneuterdijk. She would hardly ever use it. Juliana loved her university years and wanted nothing more than to be treated like any other person. She wanted real friends and made them too. Nevertheless, she was driven to classes from her villa in Katwijk, and a servant would always be waiting for her after classes. She was not allowed to take her final exams but did take three orals exams to end her studies with an honorary doctorate in 1930.

It was soon time to search for a husband for Juliana. Her mother and grandmother had both been 20 years old when they married, and Juliana was soon to be 21. Juliana herself did not consider it a priority to find a husband. She would continue to miss her university days and spent the following years in a lull.

(public domain)

(public domain)She would suffer two losses in 1934 that would hit her hard. On 20 March, her grandmother Emma died. Just four months later, her father died. Juliana was in England with her relative Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone at the time of her father’s death. Juliana had the firm belief that death was simply the start of something else, and she wrote, “Mother carefully told me today that Father had died – I long to go to her. Although, after Grandmother’s death, death means nothing more to me than lovely things and I know Mother feels that as well. Father was very cheery this morning, and it happened in a second, not in her presence. Isn’t it lovely, so sudden. I am so glad to know that ever since Grandmother died, every life ends happily by ‘death.’ I am becoming a philosopher – don’t mind me.”2 He received a funeral in white to symbolise the transition to a new life.

Henry’s death also gave Juliana a new role – that of President of the Red Cross.

The search for a husband continued relentlessly. Queen Wilhelmina may have wanted a love match for her daughter, any future husband would still need to be a protestant, healthy, foreign – preferably of equal birth – royalty but he couldn’t be an heir to any throne. Wilhelmina used her Almanach de Gotha to seek out possible candidates. The rise of Hitler in Germany hindered the search as any German Prince following him was undoubtedly excluded.

By 1935, Wilhelmina was becoming desperate, but hope was nearby. Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld presented himself to Juliana in early 1936 during a ski-trip. He didn’t quite meet all the criteria – after the Second World War, it would become clear he had joined the Nazi-party – but he looked good on paper. For Juliana, it was love at first sight.

Part three coming soon.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelma – The Youth of Princess Juliana (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 29, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The birth of Princess Juliana (Part one)

At the end of 1908, it was announced that Queen Wilhelmina was again pregnant. By then, she had suffered two miscarriages and the stillbirth of a son. There were immediately several concerns. What would happen if Wilhelmina died in childbirth? Who would act as regent for the minor child? There were only two obvious candidates: her husband Henry and her mother Emma. Emma would undoubtedly be preferred, not only because she already had eight years experience as regent and she was quite popular. Wilhelmina also preferred her mother as regent and early the following year, Emma was officially appointed as regent if the worst should happen.

Meanwhile, Wilhelmina’s pregnancy was advancing well. Wilhelmina spent some time writing a manual as to how the child should be raised if she died. Wilhelmina passed her due date, but labour finally began on 28 April 1909, but it was a slow labour, and Wilhelmina gave birth to a daughter just before 7 A.M. on 30 April at Noordeinde Palace.

An heir to the throne, at last. It didn’t even matter to the celebrating crowds that the child was “only” a girl; anything was better than a German prince. Wilhelmina decided to feed the newborn Princess herself for nine months.

On 5 June 1909, the Princess was baptised with the names: Juliana Louise Emma Marie Wilhelmina. She received the name Juliana in honour of her ancestress Juliana of Stolberg, the mother of William the Silent.

Wilhelmina later wrote in her memoirs, “She was a strong and healthy child, always a little in advance of her age in intelligence and knowledge. I must leave it to the reader to imagine our parental happiness at her arrival after we had waited for eight years. Of course, she changed our lives in many ways. In summer and autumn, I considered myself exempt from many duties which had no direct bearing on my official task. As soon as I had a moment free, I lived only for my child.”1

Juliana was nicknamed “Jula” by her family, and she became the apple of her mother’s (and father’s) eye.

Part two coming soon.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The birth of Princess Juliana (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 28, 2020

Marie Eleonore of Albania – A story of courage and suffering

We are all familiar with the tragic story of Princess Mafalda of Savoy, the daughter of King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, who was arrested by the Gestapo in 1943, sent to Buchenwald concentration camp where she died a year later. But there is another royal story that is far less famous but equally tragic and sad; the one of the German Princess, Marie Eleonore of Albania.

Born on 19 February 1909 in the city of Postdam, she was the only daughter of William, Prince of Albania (born Prince William of Wied) and his wife Princess Sophie of Schönburg-Waldenburg. Her father was a nephew of Queen Elisabeth of Romania, and this is quite interesting for our story as Romania will have a tragic and important place in the life of the Princess.

In 1914, her father became a Prince of Albania, and the whole family moved to Albania, where they were met with genuine enthusiasm by the locals. However, this would be a short-lived adventure. After just six months, the new sovereign was overwhelmed by the serious internal problems of his host country on the verge of the First World War. He was exiled in September 1914 and Albania became a republic in 1925. Marie Eleonore developed a great love for nature and animals, and even a serious horse-riding accident in 1921 could not dissuade her. In 1925, the family came to live in Romania at the invitation of their royal relative, Queen Elisabeth. Prince William and Princess Sophie stayed in Romania for the rest of their lives.

Marie Eleonore attended a girls’ high school in Munich, and she spent a year at the agricultural college in Hohenheim. She also studied economics and political science at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. She even studied in the United States for two years on a scholarship. On 13 November 1937, she completed her doctorate in Berlin with the thesis, “The International Capital of South America.” She graduated magna cum laude. Just three days later, on 16 November 1937, she married Prince Alfred of Schönburg-Waldenburg, a relative. The young couple settled in München. History doesn’t tell us if it was a happy marriage, but it was a short one. Four years later, Prince Alfred died during the Second World War of an illness. Finding herself alone in Germany in the middle of the war, Princess Marie Eleonore decided to return to Romania where her parents were still living in Fontaneli Castle.

Marie Eleonore did her bit during the Second World War by joining the Romanian Red Cross. However, the heavy work eventually led to a complete mental and physical breakdown. She recovered and returned to work. At the end of the war in 1945, she was an established presence in the intellectual and cultural circles of the Romanian society. During a cultural gathering, she met a young lawyer named Ion Bunea, who would become her second husband in 1948. However, as the Russian army closed in, Marie Eleonore and her father – her mother had died in 1936 – escaped by car, fleeing to Sinaja, the summer residence of King Michael I of Romania, who gave them an apartment on his estate. Marie Eleonore nursed her father there until his death on 18 April 1945. She then moved to Bucharest and married Ion Bunea on 4 February 1948.

In the 1950s, Romania underwent a period of cultural and economic isolation triggered by the new Communist regime imposed by the Soviet Union. The Romanian authorities decided to close many of the leading cultural institutions in the country, like the French Institute, the British and American press offices. Princess Marie Eleonore (a Romanian citizen by marriage) was one of the employees of the British information office, and she was arrested by Securitate (the secret police agency in Romania) and accused of treason. Before being arrested, she gave a large part of the family jewellery to British diplomats for safeguarding in the UK.

Princess Marie Eleonore, as a relative of the Romanian royal family, was forced into exile by the Communist regime in 1948, another element that weighed heavily in the judicial trial that was opened in her name. She was condemned to 15 years of forced labour, and all her material possessions were confiscated by the state. Her husband was also convicted to five years of forced labour.

In 1956, after six years of incarceration, the Princess died at the Miercurea Ciuc Penitentiary, a political prison for women in Romania. Aged only 46, she couldn’t handle the inhumane conditions of detention. In early 1956, she had fallen ill with tuberculosis. She died following a bowel surgery on 29 September 1956.

Marie Eleonore, who was a daughter of a sovereign and a relative of the most important royal families in Europe, doesn’t even have a grave. She disappeared along with other tens of thousands of women deemed as dangerous by the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe. She is probably buried somewhere on the prison grounds. Their heroism and solid moral principles that transcend social classes and geography should be treasured as an example of courage and goodness in a world that proved to be cruel and inhumane so many times in history.

A nun who was incarcerated with her later said, “I can not forget her because in the midst of our dark presence her essence shone, just, sincere, mindful of the essential people, with great tenderness and kindness towards the suffering. She saw the human being in each of us without distinction.” 1

April 27, 2020

Theodora of Greece and Denmark – A Princess without fortune

Theodora of Greece and Denmark was born on 30 May 1906 at 11.45 P.M. at Tatoi Palace as the second daughter of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg. Andrew was away at the time to attend the wedding of Alfonso XIII of Spain and Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, Alice’s cousin. Theodora was nicknamed Dolla in the family. She would be one of five siblings: Margarita (born 1905), Cecilie (born 1911), Sophie (born 1914) and Philip (born 1921).

In her childhood, she was described as being, “full of quaint ideas such as that she had seen fairies flitting about in the grounds. She used to have the funniest fits of absent-mindedness too, for which she was much derided by her very sprightly sister.”1 Theodora and her siblings were in the care of a governess, who taught them English and Greek. They also did gymnastics in a long corridor of the palace.

In 1917, the family was forced into exile for the first time. Theodora’s uncle King Constantine I of Greece abdicated in favour of his second son Alexander and Andrew and Alice went to live in St Moritz in Switzerland. Their main base became the Grand Hotel in Lucerne. Life changed again when King Alexander died in 1920 and Constantine was restored as King. Theodora and the family settled at Mon Repos where Prince Philip was born. In 1922, Theodora and her sisters were invited to be bridesmaids at the wedding of Edwina Ashley to Alice’s brother Louis (later 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma). At the time their grandmother described them as, “quite natural and unaffected girls, really children, that do Alice credit, but though nice looking, they have merely the good looks of youth.”2

More trouble was to come as King Constantine abdicated for a second time in 1922, now in favour his eldest son George. It was arranged that the King and Queen would leave with Andrew, but he was not with them when they left. Alice and Andrew remained in Corfu with the children for now. Andrew was eventually arrested, leading to much worry. He was banished from Greece, and he gathered the family from Corfu where Alice had hurriedly packed a few belongings. Baby Philip was carried in a cot made from an orange box. Margarita and Theodora were left in the care of their grandmother in England, while Alice took the younger three siblings to Paris into the care of Andrew’s sister-in-law Princess Marie Bonaparte, the wife of Prince George of Greece and Denmark. She loaned the family a house in France where they would eventually live with the entire family.

Margarita and Theodora spent the autumn of 1923 at Kensington Palace, Christmas at Holkham and the new year at Sandringham. In January 1924, they attended the state opening of Parliament. In July, they were at the 30th birthday party of the Prince of Wales (future King Edward VIII) at Spencer House. However, as exiled Greek Princesses without money, they were hardly good catches, and it wasn’t until the end of the decade that either would find husbands.

Their younger sister Sophie was the first to marry. On 15 December 1930, she married Prince Christoph of Hesse. Theodora helped her sister into her dress at Friedrichshof. Cecilie married Georg Donatus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Hesse on 2 February 1931. Margarita was next to marry. On 20 April 1931, she married Gottfried, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg. Theodora was now the last of the sisters left unmarried. In June, her engagement to Berthold, Margrave of Baden, was announced. They were married on 17 August 1931 at the Neues Schloß in Baden-Baden. Alice wrote, “I do hope Dolla will have a very happy life with Berthold because I think in some ways, she expects more than her sisters.”3 Berthold was the titular Grand Duke of Baden as the Grand Duchy had been abolished in 1918, along with many other German monarchies.

On 24 July 1932, after a twelve-hour labour – Theodora gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Margarita. A son named Maximillian was born on 3 July 1933, followed by a second son named Ludwig on 16 March 1937. Tragedy struck in November when Theodora’s sister Cecilie was killed alongside her family in an aeroplane crash. The funeral took place on 23 November, and Theodora attended it with her husband.

Early into the Second World War, Berthold was injured in the leg in France and was recovering at Giessen. He was left with a limp for life and returned home permanently. This means he had very little involvement with the Nazis and he and Theodora spend the rest of the war at their home in Salem. Though quite far away from the troubles of war, by the end of it, even Theodora was “sad and depressed.”4

Theodora and her surviving sisters came into some prominence when their younger Philip married the future Queen Elizabeth II. They had wanted to attend the wedding in 1947, but due to the anti-German sentiments at the time, it was decided that none of them would be invited to the wedding. Margarita, Sophie and Theodora went with Princess Elisabeth of Greece and Denmark (Countess of Törring-Jettenbach) – their first cousin – and the late Cecilie’s brother-in-law Louis and his wife Margaret to Marienburg where they celebrated the wedding together. Their mother Alice did attend the wedding, sitting on the north side of Westminster Abbey. She sent her daughters a 22-page description of the wedding.

In December 1949, just as her mother came to visit, Theodora began to suffer heart problems, which turned out to be a lasting problem. Theodora’s sister-in-law Princess Elizabeth became Queen in 1952 and Theodora and her sisters found themselves being invited to the coronation. They joined their mother Alice in the royal box behind Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. Theodora’s health continued to deteriorate with her mother commenting that she looked “old & haggard” after the wedding of Princess Sophia of Greece and Denmark and the future King Juan Carlos I of Spain in 1962. Alice later wrote to Philip, “There are days, she speaks with great difficulty & can’t manage her legs & then after some hours that passes & she talks & walks normally. For that reason, she walked about with a stick here as she never knows when these periods come on. It is the arteries narrowing so much more & preventing blood going to her head. Also, her heart is much worse. I thought I would warn you, as no one warned me.”5

In July 1963, Theodora had all her teeth extracted and was now sporting, “a dazzling smile to which one has to get accustomed.”6 She was apparently feeling better, and at the end of September, she went on a tour of Italy. She wasn’t with her husband when he suddenly slumped over dead in a car on his way to Baden-Baden with their son Ludwig on 27 October 1963. In 1965, Queen Elizabeth II visited Theodora with Philip. Margarita and Sophie also came to dinner.

Theodora died suddenly on 16 October 1969 at the Sanatorium Buedingen in Constance. She had moved there following an earlier hospitalisation. Philip’s son Charles flew to Salem to attend the funeral. Alice outlived her daughter for just five weeks – dying on 5 December 1969.

April 26, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The young Queen meets the old Queen

In the early morning of 27 April 1895, the royal yacht De Valk brought two Countesses van Buren from Vlissingen to Queenborough. In reality, the Countesses were, in fact, Queen Emma and the 14-year-old Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands. From Queenborough, the Queens took the train to London where they were received by the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) and the Duchess of Albany, who was Emma’s sister.

The two Queens stayed at the Brown’s Hotel at Albemarle Street. That same day, they visited the National History Museum, followed by a carriage ride through Hyde Park. The following day, they attended a service at the Church of Austin Friars, known as the Dutch church. In the afternoon, they met with the Duchess of Albany again at Claremont House after taking the train from London Waterloo.

The next two days, the young Queen spent several hours at the British Museum to continue her education. Nevertheless, there was still plenty of shopping done, and she also watched the Changing of the Guard in front of St James’s Palace.

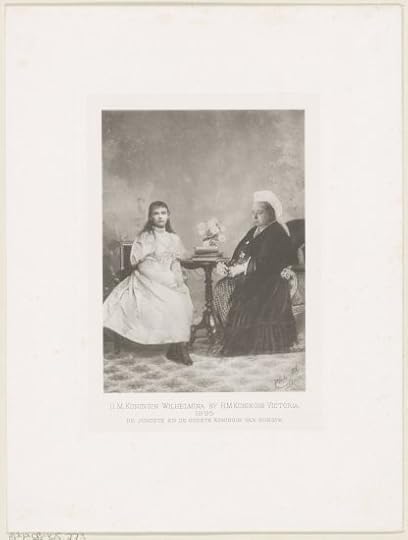

On 2 May, the Queens visited Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. On 3 May, the youngest Queen of Europe met the eldest – Queen Victoria. They had lunch together before taking a drive. Queen Victoria wrote in her journal, “Shortly before two, went downstairs to receive the Queen Regent of the Netherlands and her daughter… The young Queen, who will be fifteen in August, has her hair hanging down. She is very slight and graceful, has fine features, and seems to be very intelligent and a charming child. She speaks English extremely well, and has very pretty manners.”1 For the occasion, a now-famous photo was made, but it was, in fact, two photos photoshopped together.

(public domain)

(public domain)The following days were again spent shopping. On 7 May, they visited the Tower of London and had lunch with the Prince and Princess of Wales and their three daughters at Marlborough House. The Prince of Wales had met with Wilhelmina’s half-brother William, Prince of Orange in Paris before his death but it is unlikely they discussed the past. They also went to have tea with Mary of Teck, then Duchess of York.

The following day, they visited the House of Commons, where they listened to debates. That evening, Queen Emma had dinner with Queen Victoria without Wilhelmina. On 9 May – the final day – the two Queens had a last lunch with Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria presented Wilhelmina with a signed portrait of herself as a souvenir of their meeting. The Prince of Wales also visited them on that last day. Their cover as Countesses of Buren was definitely blown by now, so they received a full honour guard as they left.

On 10 May, they were back in the Netherlands. From Friedrichshof, Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter wrote to her mother, “I am very glad the visit of the Queen of the Netherlands went off so well; I should much like to see them. I have the greatest respect for Queen Emma… The young Queen must be a charming and interesting girl…2

In her memoirs, Wilhelmina wrote of the trip, “In 1895 Mother took me to England, for ten days or perhaps a little longer. It was not just a pleasure trip; Professor Krämer accompanied us in order to guide me round the British Museum, where I had to see the Assyrian, Egyptian and Greek antiquities. The museum aroused little interest in me, all the other things I found very exciting. What an experience: to see London in the spring, and to have so many unexpected things happening. I suppose Mother also wanted me to meet Queen Victoria’s large family, for I went on several visits with her and also accompanied her on several luncheons. The visit took on momentarily an official character when we went to pay our respects to the old Queen at Windsor, but otherwise, we were free in our movements. We saw my mother’s sister, Aunt Helena, at Claremont, where I played with my cousins. We had luncheon with the future King Edward VII at Marlborough House and paid a visit to his daughter-in-law, the future Queen Mary, at St James’s Palace. Her first child had not yet begun to walk at that time, and the King, who died a few years ago had not been born3. What a long time ago!”4

When Queen Wilhelmina met Queen Victoria again in 1898 in Nice, she was presented with the Order of Victoria and Albert.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The young Queen meets the old Queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 24, 2020

Bertrade de Montfort – ‘Whom no good man ever praised save for her beauty’

Late 11th century France was shocked when their king, Philip I, left his wife for the already-married Bertrade de Montfort. Bertrade’s husband, Fulk IV, Count of Anjou, also had a questionable marital history himself. As for Bertrade, she was seen as a temptress, a beautiful but immoral woman.

Countess of Anjou

Bertrade was born around 1070, as the daughter of Simon I of Montfort and Agnes of Evreux. Her family was based in the Duchy of Normandy. In 1087, after the death of her father, Bertrade was placed under the care of her maternal uncle, the Count of Evreux. Apparently, this was around the time when Fulk IV of Anjou first noticed her. At the time, Fulk was married to his fourth wife. His first wife had died during their marriage, and he divorced each of his following ones. Fulk divorced for the third time in the same year, and in 1089 he married Bertrade. According to the chronicler, John of Marmoutier: “The lecherous Fulk then fell passionately in love with the sister of Amaury de Montfort, whom no good man ever praised save for her beauty.”

By 1092, Bertrade had given her husband a son, also named Fulk. Her marriage would not last long. That same year, she caught the attention of King Philip I of France.

Bertrade runs off with the King

(public domain)

(public domain)In May 1092, Philip met with Fulk at Tours. There he also met Bertrade. Philip was trying to repudiate his current wife, Bertha of Holland. Bertha had given him three children, of which a son and a daughter survived. Tired of Bertha, Philip sent her away the year before and had her imprisoned. At the time he met Bertrade, he was planning on marrying Emma of Sicily. However, the meeting with Bertrade ended all of those plans. On 16 May 1092, Bertrade left her husband and Anjou with the King. There are various speculations about what led to this event. Did Bertrade and Philip fall in love? Was Bertrade hungry for power? Was Philip plotting against Fulk? Whatever the truth, this was to cause a huge scandal for them both.

Bertrade and Philip married that fall, but their marriage was not seen as valid by the church. Yves, Bishop of Chartres, was the first to oppose the marriage. He refused to attend the wedding, and then he wrote to the Pope about the adulterous union. When Philip found out about this, he had the Bishop jailed. The Pope was also opposed to this union and excommunicated Philip and Bertrade.

Philip’s first wife Bertha died in 1093, but her death did not settle things. Philip and Bertrade remained excommunicated, and France was placed under interdict. In 1096, Philip lied to the Pope, saying that he set Bertrade aside. The Pope believing this, lifted the interdict, but not the excommunication on Philip and Bertrade. Despite the opposition from the church, Bertrade was recognised as Queen.

Philip and Bertrade had three children together: two sons named Philip and Fleury, and a daughter named Cecile. By his first marriage, Philip had a daughter, Constance, and a son, Louis. Louis, being the oldest son was, of course, Philip’s heir instead of Bertrade’s sons.

Rumours about Bertrade trying to poison Louis, in order for her own son to become king, were started. It is hard to tell if there was any truth to these rumours. The excommunication of Philip and Bertrade was finally lifted in 1104. Bertrade’s first husband Fulk never married again. Oddly enough, in 1106, Philip and Bertrade returned to Anjou. There, Fulk warmly welcomed them and threw them a grand feast.

From Scandalous Queen to Nun

Philip died in 1108. At one point, Philip, Bertrade’s older son by the king revolted against his half-brother, Louis, trying to take the throne. It’s not certain if Bertrade was involved in this. Later, Bertrade ironically retired to the religious life. She became a nun in 1115 and founded the priory of Haute-Bruyere. She died at her priory in 1117 and was buried there.

Although Bertrade’s son never became king of France, Fulk, her son from the first marriage later became King of Jerusalem. Also through Fulk, she was an ancestor of the Plantagenet dynasty.1

The post Bertrade de Montfort – ‘Whom no good man ever praised save for her beauty’ appeared first on History of Royal Women.