Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 182

April 23, 2020

Eileen – The Hereditary Princess of Albania

Eileen Johnston was born on 3 September 1922 as the daughter of George Johnston and his wife, Alice Percival in Chester, England.

Not much is known about her youth. On 6 November 1943, she first married André de Coppet, a director of the Continental Bank and Trust Company of New York. Her new husband had previously been married to Muriel Johnson Belasco but they were officially divorced in August 1943. They spent their honeymoon in Sea Island, Georgia.1 They went on to have two daughters together: Diane (born 19442) and Laura (born 19463) Her husband died in August 1953 after suffering a heart attack.4

On 8 September 1966, Eileen married Carol Victor, Hereditary Prince of Albania. He was the only son of William, Prince of Albania, who briefly ruled the Principality of Albania. The ceremony took place at the St. James Episcopal Church with her daughters from her first marriage attending on her. The wedding announcement stated that they would divide their time between Munich and New York.5 They would not have any children together, leading to the extinction of his line.

Eileen was widowed again when Carol Victor died on 8 December 1973. Eileen survived him for 12 years. She died on 1 September 1985 in New York and was buried with her first husband at Woodlawn Cemetery in New York.

The post Eileen – The Hereditary Princess of Albania appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 22, 2020

Elisabeth of Valois – “A right Spaniard!”

Elisabeth of Valois was born on 2 April 1545 as the daughter of King Henry II of France and Catherine de’ Medici. She was born in the Château de Fontainebleau. Elisabeth was their second child. Her elder brother was King Francis II of France, who was married to Mary, Queen of Scots. She would have a total of nine siblings, though four of those would die in infancy.

In 1548, Elisabeth was lodged with her future sister-in-law, Mary, Queen of Scots, in the nursery. Catherine wrote, “The said Lord wished Madame Ysabal (Elisabeth) and the Queen of Scotland should be lodged together, wherefore you will select the best chamber… for it is the said Lord’s wish that they get to know one another.”1 The two would grow quite close over the years. The royal nursery was under the supervision of Diane de Poitiers, King Henry II’s mistress. The Valois children, with the exception of Margaret, were all known to be rather sickly.

From an early age, Elisabeth was part of marriage negotiations; she was even considered for King Edward VI of England. After his death, she was considered for Don Carlos, King Philip II of Spain’s heir. However, when Philip himself was widowed for the second time with the death of his wife Queen Mary I of England, she was considered for the King himself. On 22 June 1559, the proxy wedding between the 13-year-old Elisabeth and the 32-year-old King Philip II took place at the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris with the Duke of Alba standing in for the King. Later that day, they ceremoniously got in a bed together and touched their bare legs together, and so the marriage was “consummated”. A few days later, the celebratory jousts began, but they would have a tragic ending. On 30 June 1559, Elisabeth’s father was injured in a jousting accident, and he died on 10 July. With his dying breath, he asked Catherine to make sure that his sister Margaret’s wedding to the Duke of Savoy would go ahead, which it did on 9 July.

It was, in fact, Elisabeth’s younger sister Claude who would leave France first. She had been married in January to Charles III, Duke of Lorraine. Then on 18 November, Margaret departed for Savoy. That very same day, Catherine joined Elisabeth for the first part of her journey to France. One week later, Elisabeth bade her mother farewell at Châtellerault. Her mother was in tears at her daughter’s departure, and this was the start of an extensive correspondence between the two Queens. On 30 January 1560, Elisabeth first met her new husband King Philip in Guadalajara, and she described herself as the luckiest girl in the world to have such a husband. Philip too declared his complete happiness. The wedding was formalised on 31 January in the palace of the Dukes of Infantado. She wore a silver dress with pearls and precious stones. She also wore a diamond necklace. Philip wore a white doublet with a crimson cloak. The wedding was followed by a banquet and a ball. The next day there were bullfights, jousting and a hunt.

Elisabeth did not have her first period until August 1561 and Philip continued to have mistresses. Despite her knowledge of this, their domestic life was rather harmonious. She even managed to befriend Philip’s unstable son and cried for days when Philip eventually had him locked up. The following year, Elisabeth briefly returned to France, but Catherine told her she had become “a right Spaniard!”2 After suffering several miscarriages, including twins, Elisabeth gave birth to two daughters, Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain on 12 August 1566, and Catherine Michelle of Spain on 10 October 1567.

When Elisabeth had become ill during her first pregnancy in 1564, the doctors bled her from her arm and temple. She had been so frightened at the prospect of being bled that she had called upon her husband to hold her hand. The procedure upset Elisabeth so much – having never been bled before – that she miscarried. She grew even weaker when blisters were applied to her feet and hands.3

Elisabeth never quite recovered from the birth of Catherine Michelle. She became pregnant again and was quite ill as a result. By the middle of September 1568, she was suffering from fevers, and she was feeling faint. On 3 October 1568, she died “after a stillbirth an hour and a half before of a girl of four or five months, who was baptised and went to heaven with her mother.”4 The little girl was named Joanna. Philip was devastated. Catherine too was devasted when she learned the news two weeks later, but the pragmatic Queen regent told her council, “King Philip will certainly remarry. I have, but one wish and that is for my daughter Margaret to take the place of her sister.”5

King Philip remarried a fourth and final time to his niece, Anne of Austria, who gave him five further children of whom only the future Philip III would survive infancy. Elisabeth was buried at El Escorial in the Pantheon of the Infantes (Princes), as opposed to the Pantheon de Reyes (Kings), because she was not the mother of a King.

The post Elisabeth of Valois – “A right Spaniard!” appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 21, 2020

Suriyothai – The Queen who died in battle

Queen Suriyothai of Ayutthaya (a Siamese Kingdom in present-day Thailand) was the wife of Maha Chakkraphat, King of Ayutthaya.

Tragically, very little is known about Suriyothai. We know that she and her husband had at least five children together: Phra Ramesuan, Phra Mahin (later King Mahinthrathirat), Phra Sawatdirat, Phra Boromdilok and Phra Thepkassatri. Suriyothai is most remembered for her death in battle.

Barely six months into her husband’s reign, King Tabinshwehti of Burma invaded Siam intending to sack the capital Ayutthaya. The invading forces initially had little resistance, but soon King Maha Chakkraphat mobilised his forces and gathered them just west of Ayutthaya. He was accompanied by Queen Suriyothai and one of their younger daughters Boromdilok. He rode his chief war elephant, while Queen Suriyothai and her daughter rode a smaller elephant together. They were also dressed in armour, and Queen Suriyothai wore the uniform of a viceroy. Their two eldest sons were also with them.

As the two armies engaged in battle, the King engaged with the Viceroy of Prome. The King’s elephant panicked and fled, with the Viceroy chasing them. Queen Suriyothai charged ahead to put her elephant between them. The Viceroy then turned on her, cleaving her from shoulder to heart with a spear, while also fatally wounding her daughter. As she died, her helmet came off, exposing her long hair. Her sons fought off the Viceroy before carrying the bodies of their mother and sister back to Ayutthaya.

Her husband built a memorial dedicated to her. In addition, there is a memorial park outside of Ayutthaya with a large statue of her riding a war elephant. A 2001 movie called The Legend of Suriyothai was financed by Queen Sirikit of Thailand.

The post Suriyothai – The Queen who died in battle appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Private footage of young Queen Elizabeth II released to mark birthday

The official Royal Family Twitter channel has released private footage of the Queen as a child. See the lovely footage below.

Thank you for your messages today, on The Queen’s 94th birthday.

April 20, 2020

Louise of Belgium – An incredible story of survival (Part two)

“But what terrible hours I have passed! What nights of agony! What horrible nightmares! What tears, what sobs! I tried in vain to control myself.”1 For four long years, Louise, declared insane and ostracised by the royal courts of Europe, languished in insane asylums. She was finally moved to Lindenhof, where she regained some freedoms, but she still described it as a “gilded cage” and a “tomb.”2 Her aunt the Countess of Flanders (born Marie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen) and her daughter eventually came to visit her. She never heard from her father. Her mother died in 1902, and they never saw each other again. They had written to each other while Louise was incarcerated, but as she wrote, “I felt that my mother had been convinced that I was really insane.”3

After four years, Count Geza Mattachich was pardoned for his so-called crimes, and he soon began to plan for Louise’s escape but it would three more years before he was able to free her. Louise was allowed to travel to Bad-Elster to take the waters, but she would still be well-guarded. The Count passed messages to Louise through a waiter in the hotel where she was staying, finally giving Louise some hope. Somehow, the night watchman was in on the escape, and Louise received a communication that read, “It will be tomorrow.”4 It was August 1904 and Louise would finally be free again. During the night, Louise anxiously awaited a signal with her dog Kiki by her side. The nightwatchman came to fetch her and the little belongings she had managed to pack without arousing suspicion. He led her to the ground floor, where she found the Count waiting for her. Through the darkness, they walked to a waiting carriage. Eventually, they made their way to Berlin where they caught the Orient Express to France via Belgium.

As she crossed into Belgium, one superintendent asked the Count, “It is our Princess, is it not? Do not be afraid. Nobody will betray her.”5 Incredibly, their plan had worked. They arrived in Paris, where they set out to prove that Louise was sane. French physicians interrogated and examined Louise, declaring her to be sane. However, she was still left without money, and the immense inheritance she expected to receive would not be forthcoming. Her father promptly removed her from his will when her divorce from Prince Philipp finally became final in 1906. Louise began legal proceedings, but her father died in 1909 without having resolved the issue. She would be given an allowance from the Belgian government, but she did not receive any money until the end of the First World War.

Louise was in Vienna when the First World War was declared, and the Austrian court immediately declared her an “enemy subject”, and she was asked to leave as soon as possible. She intended to go to Belgium but ended up stranded in Munich. For two years, she lived there with the indulgence of the Bavarian court. The German victories in Europe made the Bavarians less willing to host her, and she ended up at the mercy of her son-in-law, Ernst Günther, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, who wanted her to sign over her rights to any inheritance she might receive from her aunt Charlotte, the unfortunate Empress of Mexico. The Count was forced to leave Munich and was deported back to Croatia. She was now penniless and alone, again. Louise found her way Hungary and was there when the Austrian Empire collapsed. She was mocked with the words, “Here is a King’s daughter who is poorer than I am.”6

She began writing her memoirs, which were published in 1921. The final pages in the memoirs are dedicated to the Count, “This spirit of sacrifice is peculiarly your own. I never possessed it. But you have endowed me with it. No gift has ever been so precious to my soul, and I shall be beyond grateful to you on this side of the tomb and beyond it. I, who alone know you as you really are, and know the adoration that has given you a reason for living, I thank you, Count, in the twilight of my days for the nobility which you have always shown in this adoration? Shall I ever know, will you ever know, the meaning of rest otherwise than the last rest, which is the lot of mankind?7

Louise’s beloved Count died in 1923. Louise died on 1 March 1924 of pneumonia at the age of 66 in Wiesbaden. She was buried at Wiesbaden’s Südfriedhof.

The post Louise of Belgium – An incredible story of survival (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 19, 2020

Louise of Belgium – An incredible story of survival (Part one)

“I was born a King’s daughter. I shall die a King’s daughter.”1

Louise Marie Amélie of Belgium was born on 18 February 1858 as the eldest child of King Leopold II of Belgium and his wife, Marie Henriette of Austria. She was not the longed-for male heir, but a little brother named Leopold was born the following year, followed by a sister named Stéphanie in 1864 and another sister named Clémentine in 1872. As the eldest child, she was expected to set the example for her younger siblings. The children were raised in the English fashion with very sober bedrooms.

Life changed forever when young Leopold fell into a pond and developed pneumonia. He died on 22 January 1869 at the age of 9 – leaving behind a devastated family. Her mother never quite recovered, and it left her father without an heir as Belgium did not allow women to ascend the throne at that time. Louise later wrote of her little brother, “Leopold, handsome, sweet, sincere, tender and intelligent, embodied for me, after our mother, all that was most precious in the world – I could no more conceive existence without him than the day without light. But he could not stay… and I still weep for him, although it is more than fifty years since he left me.”2

Louise’s relationship with her father was distant, and she always some him more as her King than as her father. She was a bit close to her mother, and she enjoyed going out on drives with her. She loved living at the Castle of Laeken with its gardens and open space. During her education, she received the nickname “Madame Pourquoi (Miss why)” because she always asked a lot of questions.

Louise was still only 15 years old when she was officially betrothed to her second cousin, Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who was also 14 years older than her. He had already proposed twice before, but her father had advised him to travel first. He disliked the match but her mother like Philipp because it would allow Louise to live at the Austrian court. They were married on 4 February 1875 in Brussels by Mayor Jules Anspach. Louise had been left uninformed of what would happen during the wedding night. She later wrote in her memoirs, “I fell from my heaven of love to what was for me a bed of rock and a mattress of thorns.”3 After Philipp left in the early morning, Louise fled outside in her nightgown, cloak and slippers to hide in the Orangery amongst the camellias. As she wrote, “I whispered my grief, my despair, and my torture to their whiteness, their freshness, their perfume and their purity, to all that they represented of sweetness and affection, as they flowered in the greenhouse, and lit up the winter’s dawn with a warmth, silence and beauty which me back a little of my lost Paradise.”4 She was found by a sentry who brought her back to the apartments where her mother was waiting for her.

But as Louise calmed down from a nightmarish night, her departure from Belgium was being prepared. She was not allowed to bring any of her own maids with her and so left Belgium young, frightened and alone with a man she barely knew. During the early weeks of their marriage, Philipp forced her to drink more than she was used to and often made dirty jokes at her expense. On 19 July 1879, Louise gave birth to her first child – a son named Leopold. A daughter named Dorothea was born on 30 April 1881. Louise had not wanted Philipp to be present at the birth of Dorothea and hid her labour pains for as long as she could. When a midwife was finally fetched for Louise, she arrived too late, as did Philipp.

When Louise arrived at the Imperial Court of Emperor Franz Joseph and his dazzling wife Elisabeth (Sisi), she was most impressed by the Emperor. However, she would later write, “At his birth, nature deprived him of a heart. He was an emperor, but he was not a man. He is best described as an automaton dressed as a soldier.”5 Her own sister would also come to know the Austrian court quite well. In 1881, Stéphanie married the Emperor’s only son Crown Prince Rudolf. After one of the Emperor’s brothers accused her of keeping bad company – which she absolutely denied – and the Emperor sided with his brother, Louise lost the Imperial favour, much to Philipp’s anger. Louise demanded that he would defend her honour by duelling with the Emperor’s brother, which he refused to do. Louise then told him they should travel for a year, “and if at the end of that time we have not found a better way of living together we will part; you must go your way, and I will go mine.”6

A divorce seemed like it would be impossible. Louise and Philipp began to lead separate lives, and both had lovers. But while it was almost expected of Philipp to have affairs, Louise’s affairs were scandalized. One of her first lovers was Baron Nicolas Döry de Jobahàsa, but the affair was abruptly ended when the family learned of it. Louise began to live an extravagant lifestyle, racking up debt. She set her heart upon a divorce when she found love with Count Geza Mattachich. Louise took her daughter Dorothea and left for France to be with the Count. It even came to a duel between Philipp and the Count. Louise wanted to flee to England to seek the protection of Queen Victoria, but she ended up going to Croatia, to the home of the Count’s stepfather. She believed herself to be safe there and continued her quest for a divorce. The Count was eventually arrested for fraud, apparently for forged bills which Louise thought was an “invention.”7 Louise too was snatched from her bed and taken to the Doebling Lunatic Asylum where she was put in a cell. Her husband gave her an ultimatum, return to him or remain in the asylum. She chose the latter.

She later wrote in her memoirs of her time in several asylums, “At Doebling, and afterwards, at Purkesdorf, my tortures would have been beyond human endurance if I alone had been obliged to suffer. But with the hope of Divine justice, the knowledge that another was submitting to a worse punishment solely on my account gave me strength to endure. The loss of honour is as terrible as the loss of reason.”8

Part two coming soon.

The post Louise of Belgium – An incredible story of survival (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 18, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The life of Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Prince Consort

Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was born on 19 April 1876 as the youngest son of Frederick Francis II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and his third wife, Princess Marie of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. When he was seven years old, his father died and he was succeeded by Henry’s much older half-brother who became Frederick Francis III, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. The family often spent the winter months at Schwerin and the summer months at Heiligendamm or Rabensteinfelt. The latter was also intended as a dower residence for Henry’s widowed mother. Henry learned to hunt at Rabensteinfelt, and it would remain one of his favourite hobbies throughout his life.

From the age of 13, Henry attended the Vitzthum gymnasium in Dresden where he turned out to be an average student. He graduated from there in 1894 and went on an extended trip to India, Sri Lanka and Greece with a schoolfriend of his, Major Alt-Stutterheim. Upon his return, he went to the military academy and was stationed in Potsdam. He had his own villa there, and he filled it with his hunting trophies. He led quite the frivolous life in Potsdam, to such an extent that when his possible match with Queen Wilhelmina came to the attention, the Dutch court investigated his past. After three years, he had risen to the rank of captain, but he did not find fulfilment in the army and requested to leave. In 1899, he went to work for the Ministery of Finance in Schwerin.

Soon, there would be another direction in his life. His mother Marie was lifelong friends with Queen Emma of the Netherlands, regent for her daughter Queen Wilhelmina until 1898 and they believed that Henry would be perfect for Wilhelmina. In early May 1900, Emma and Wilhelmina travelled to Schwarzburg for a brief holiday where the two were formally introduced. As an “alternative” Prince Frederick William of Prussia was also invited, just in case Wilhelmina didn’t like Henry. Henry’s brother Adolf was also invited, but he did not show up. Henry and Wilhelmina had met for the first time when Wilhelmina was just 12 years old. But no matter how much Queen Emma wanted the match with Henry, Wilhelmina had already resolutely declared that she would marry “only the man that I love.”1

The following walk and picnic at the invitation of Henry’s aunt Thekla were so agreeable to Wilhelmina that she “began to wonder if a walk hand in hand through life would be recommended.”2 Upon Wilhelmina’s return to the Netherlands, she inquired into Henry’s life with her friends and family. Throughout the summer, Henry did not write to her until he asked to meet with her again in the autumn. That he did not write to her is perhaps not that strange. She might have wanted to know more about him; he would undoubtedly want to know more about what it would mean to become her consort. He would have to make sacrifices.

They met again in König in October where they were able to meet in relative privacy. However, the press soon caught on. On 12 October, Henry and Wilhelmina were briefly left alone after a lunch. After just ten minutes, they agreed on an engagement. Wilhelmina later wrote in her memoirs, “The die was cast. What a relief that always is on these occasions!”3 Wilhelmina returned home to the Netherlands, where the engagement was announced on 16 October 1900. A delighted Wilhelmina wrote to her former governess Miss Winter, “Oh darling, you cannot even faintly imagine how frantically happy I am and how much joy, and sunshine has come upon my path.”4

After heavy negotiations concerning his income, his status and titles, the two were married on 7 February 1901. Henry became known as Prince Hendrik in the Netherlands, and he became Prince Consort. He was also awarded the style of “Royal Highness.” Henry’s initial reception in the Netherlands had been somewhat lukewarm, but his popularity grew over time. One of the defining moments for this came in 1907 when the Berlin ferry – which served the Harwich/Hook of Holland route – broke in two and sank. Henry arrived the following day to help with the recovery of the bodies, but they also found a handful of survivors on the floating stern. There had been around 144 passengers on board. Once the survivors had been brought to safety, Henry helped to care for the victims and even poured them coffee or cognac. His easy-going nature also made him popular amongst the palace servants.

Though initially a happy match, Wilhelmina and Henry would grow apart over the years. She would suffer several miscarriages and a stillbirth before finally giving birth to a healthy baby girl named Juliana in 1909. She was his pride and joy until the day he died, and they always remained on good terms, despite the wavering relationship between Henry and Wilhelmina.

(public domain)

(public domain)Henry focussed his attentions on several causes, such as the merging of the Dutch Boy Scout organisations, and the Dutch Red Cross and he was the happiest outside of the court protocol. However, as he was completely dependent on his wife for money, he soon found himself in money trouble and was often loaning money from others.

Henry’s death came rather suddenly though his health had been declining for some years. He had suffered his first heart attack in 1929. On 28 June 1934, he arrived at the office of the Red Cross in Amsterdam in the early morning. Just before ten, he suffered another heart attack. He was brought to Noordeinde Palace in The Hague by ambulance as Wilhelmina was informed of his condition. Juliana was away in England at the time. He seemed to recover but suffered another heart attack on 3 July. Wilhelmina had been away to a lunch and arrived back when he had already passed away. He had requested a white funeral and no full mourning. His funeral took place on 11 July in Delft.

His inheritance was mostly debts, and he may have left several illegitimate children as Wilhelmina paid an allowance to at least three women from her own money.5

In her memoirs, Wilhelmina wrote, “Long before he died my husband and I had discussed the meaning of death and the eternal Life that follows it. We both had the certainty of faith that death is the beginning of Life, and therefore had promised each other that we would have white funerals. This agreement was now observed. Hendrik’s white funeral, as his last gesture to the nation, made a profound impression and set many people thinking.[…]The story of my life would become much too long if I tried to express what these two lives6 which were cut off so shortly after one another have meant to Juliana and me. After the funeral, we went to Norway to rest and to recover, and stayed there for six weeks.”7

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The life of Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Prince Consort appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 17, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Typhoid fever comes knocking

Queen Wilhelmina and Prince Henry had been married for just a few months when she found herself pregnant for the first time. Tragically, it would be the start of many disappointments. On 9 November 1901, she suffered a miscarriage, and the cause was not clear.

Queen Wilhelmina was ordered to bed rest for four weeks and was assured that she would completely recover. She fell pregnant again early the following year, much to her delight. She wrote to her former governess Miss Winter in late March, “We will have to go without our most enjoyable visit to Amsterdam this year as I am expecting a great event if everything goes as I have reason to hope! I am beginning the 4th month just now; I write this to show you that positive certainty is not yet possible to give, but that I have all reason to hope.”1

Wilhelmina travelled to The Loo Palace to wait out the next few months, and she arrived there on 3 April 1902. However, she soon became dizzy and took to her bed. Just one week later, doctors suspected that she was suffering from typhoid fever. Her mother Queen Emma travelled from The Hague to Apeldoorn to nurse her daughter through the illness. The diagnosis was confirmed on 18 April when the palace gates were plastered with pamphlets announcing the presence of a contagious disease.

For two weeks, the Netherlands held their breath as the young Queen fought for her life. The fear of a German Prince inheriting the throne suddenly seemed all too close. For several days, fever ravished the Queen’s body, and it wasn’t until 29 April that the newspapers reported that her condition was improving. To everyone’s great joy, she had survived, but her pregnancy had not remained unaffected. In early May, Wilhelmina gave birth to a stillborn son. Wilhelmina bravely told the doctor, “It is terribly sad, but I shall bear it.”2 Wilhelmina would remain afraid of infectious diseases.

In July when she was recovering in Schaumburg, she wrote to Miss Winter, “I knew all the time I was ill that my mother and others kept sending you news and I knew that your thoughts were with me.”3

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – Typhoid fever comes knocking appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Book News May 2020

The Habsburgs: To Rule the World

Hardcover – 12 May 2020 (US & UK)

In The Habsburgs, historian Martyn Rady tells the epic story of the Habsburg dynasty and the world it built — and then lost — over nearly a millennium, placing it in its European and global contexts. Beginning in the Middle Ages, the Habsburgs expanded from Swabia across southern Germany to Austria through forgery and good fortune. By the time a Habsburg duke was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III in 1452, he and his clan already held fast to the imperial vision distilled in its AEIOU motto: Austriae est imperare orbi universe, “Austria is destined to rule the world.” Maintaining their grip on the imperial succession of the Holy Roman Empire for centuries, the Habsburgs extended their power into Italy, Spain, the New World, and the Pacific, a dominion that Charles V called “the empire on which the sun never sets.” They then weathered centuries of religious warfare, revolution, and transformation, including the loss of their Spanish empire in 1700 and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. In 1867, the Habsburgs fatefully consolidated their remaining lands the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, setting in motion a chain of events that would end with the 1914 assassination of the Habsburg heir presumptive Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, World War I, and the end of the Habsburg era.

Cleopatra: Fact and Fiction

Paperback – 15 December 2019 (UK) & 1 May 2020 (US)

Cleopatra is one of the greatest romantic figures in history, the queen of Egypt whose beauty and allure is legendary. We think we know her story, but our image of her is largely gleaned from the film starring Elizabeth Taylor or from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. Shakespeare himself was inspired by Plutarch, who was only sixteen years old when Cleopatra died. So her story was never based purely on fact.

In the middle of the first century BC, Cleopatra caught the attention of Rome by captivating the two most powerful Romans of the day, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. She outlived both and attempted to suborn a third, her mortal enemy, Octavius Caesar, the first of the Roman Emperors. Having failed to do so she destroyed herself.

We can tell that Cleopatra was highly intelligent and politically astute and that she wielded great power. But Roman histories heaped opprobrium upon her. Cleopatra’s detractors claimed that she used her feminine wiles to entrap Caesar and Antony. She came to symbolise the danger of female influence to the safety of Rome – and indeed to the male-dominated world.

Plutarch observed that Cleopatra’s actual beauty was apparently not in itself so remarkable. It was the impact of her presence that was irresistible. Cleopatra: Fact and Fiction sheds fascinating light on the woman behind the image.

The fact that Cleopatra’s legend still burns bright today is proof of Shakespeare’s description of her as a lady of infinite variety whom custom cannot stale.

Edward II’s Nieces: The Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown

Hardcover – 3 May 2020 (US) & 22 January 2020 (UK)

The de Clare sisters Eleanor, Margaret and Elizabeth were born in the 1290s as the eldest granddaughters of King Edward I of England and his Spanish queen Eleanor of Castile, and were the daughters of the greatest nobleman in England, Gilbert ‘the Red’ de Clare, earl of Gloucester. They grew to adulthood during the turbulent reign of their uncle Edward II, and all three of them were married to men involved in intense, probably romantic or sexual, relationships with their uncle.

When their elder brother Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, was killed during their uncle’s catastrophic defeat at the battle of Bannockburn in June 1314, the three sisters inherited and shared his vast wealth and lands in three countries, but their inheritance proved a poisoned chalice. Eleanor and Elizabeth, and Margaret’s daughter and heir, were all abducted and forcibly married by men desperate for a share of their riches, and all three sisters were imprisoned at some point either by their uncle Edward II or his queen Isabella of France during the tumultuous decade of the 1320s. Elizabeth was widowed for the third time at twenty-six, lived as a widow for just under forty years, and founded Clare College at the University of Cambridge.

Queen Victoria and The Romanovs: Sixty Years of Mutual Distrust

Hardcover – 15 February 2020 (UK) & 1 May 2020 (US)

Despite their frequent visits to England, Queen Victoria never quite trusted the Romanovs. In her letters she referred to horrid Russia and was adamant that she did not wish her granddaughters to marry into that barbaric country. Russia I could not wish for any of you, she said. She distrusted Tsar Nicholas I but as a young woman she was bowled over by his son, the future Alexander II, although there could be no question of a marriage. Political questions loomed large and the Crimean War did nothing to improve relations.

This distrust started with the story of the Queen s Aunt Julie , Princess Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and her disastrous Russian marriage. Starting with this marital catastrophe, Romanov expert Coryne Hall traces sixty years of family feuding that include outright war, inter-marriages, assassination, and the Great Game in Afghanistan, when Alexander III called Victoria a pampered, sentimental, selfish old woman . In the fateful year of 1894, Victoria must come to terms with the fact that her granddaughter has become Nicholas II s wife, the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. Eventually, distrust of the German Kaiser brings Victoria and the Tsar closer together.

Permission has kindly been granted by the Royal Archives at Windsor to use extracts from Queen Victoria’s journals to tell this fascinating story of family relations played out on the world stage.

Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa (Ohio Short Histories of Africa)

Paperback – 15 May 2020 (US & UK)

In this unapologetically African-centered monograph, Nwando Achebe considers the diverse forms and systems of female leadership in both the physical and spiritual worlds, as well as the complexities of female power in a multiplicity of distinct African societies. From Amma to the goddess inkosazana, Sobekneferu to Nzingha, Nehanda to Ahebi Ugbabe, Omu Okwei, and the daughters or umuada of Igboland, Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa documents the worlds and life histories of elite African females, female principles, and (wo)men of privilege.

Chronologically and by theme, Achebe pieces together the worlds and experiences of African females from African-derived sources, especially language. Achebe explores the meaning and significance of names, metaphors, symbolism, cosmology, chronicles, songs, folktales, proverbs, oral traditions, traditions of creation, and more. From centralized to small-scale egalitarian societies, patrilineal to matrilineal systems, North Africa to sub-Saharan lands, Female Monarchs and Merchant Queens in Africa offers an unparalleled history of the remarkable African women who occupied positions of power, authority, and influence.

The Creation of the French Royal Mistress: From Agnès Sorel to Madame Du Barry

Hardcover – 1 May 2020 (US & UK)

Kings throughout medieval and early modern Europe had extraconjugal sexual partners. Only in France, however, did the royal mistress become a quasi-institutionalized political position. This study explores the emergence and development of the position of French royal mistress through detailed portraits of nine of its most significant incumbents: Agnès Sorel, Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, Diane de Poitiers, Gabrielle d’Estrées, Françoise Louise de La Baume Le Blanc, Françoise Athénaïs de Rochechouart de Mortemart, Françoise d’Aubigné, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, and Jeanne Bécu.

Beginning in the fifteenth century, key structures converged to create a space at court for the royal mistress. The first was an idea of gender already in place: that while women were legally inferior to men, they were men’s equals in competence. Because of their legal subordinacy, queens were considered to be the safest regents for their husbands, and, subsequently, the royal mistress was the surest counterpoint to the royal favorite. Second, the Renaissance was a period during which people began to experience space as theatrical. This shift to a theatrical world opened up new ways of imagining political guile, which came to be positively associated with the royal mistress. Still, the role had to be activated by an intelligent, charismatic woman associated with a king who sought women as advisors. The fascinating particulars of each case are covered in the chapters of this book.

Thoroughly researched and compellingly narrated, this important study explains why the tradition of a politically powerful royal mistress materialized at the French court, but nowhere else in Europe. It will appeal to anyone interested in the history of the French monarchy, women and royalty, and gender studies.

Lust, Lies and Monarchy: The Secrets Behind Britain’s Royal Portraits

Paperback – 1 May 2020 (US)

People have long been fascinated by the stories behind royal portraits. This volume takes readers inside royal families by way of great paintings, like Holbein’s Henry VIII, van Dyck’s Charles I, Millais’ The Princes in the Tower, Freud’s Elizabeth II, and more. Featuring incredible, little known stories of the royals and illustrates, this beautiful collection is illustrated with color paintings, photos, family trees and Royal London walking tours with maps.

Medieval Women on Film: Essays on Gender, Cinema and History

Paperback – 12 May 2020 (US) & 30 January 2020 (UK)

In this first ever book-length treatment, 11 scholars with a variety of backgrounds in medieval studies, film studies, and medievalism discuss how historical and fictional medieval women have been portrayed on film and their connections to the feminist movements of the 20th and 21st centuries. From detailed studies of the portrayal of female desire and sexuality, to explorations of how and when these women gain agency, these essays look at the different ways these women reinforce, defy, and complicate traditional gender roles.

Individual essays discuss the complex and sometimes conflicting cinematic treatments of Guinevere, Morgan Le Fay, Isolde, Maid Marian, Lady Godiva, Heloise, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and Joan of Arc. Additional essays discuss the women in Fritz Lang’s The Nibelungen, Liv Ullmann’s Kristin Lavransdatter, and Bertrand Tavernier’s La Passion Beatrice.

Sophia – Mother of Kings: The Finest Queen Britain Never Had

Paperback – 30 May 2020 (UK) & 2 September 2020 (US)

When Sophia Dorothea of Celle married her first cousin, the future King George I, she was an unhappy bride. Filled with dreams of romance and privilege, she hated the groom she called pig snout and wept at news of her engagement. In the austere court of Hanover, the vibrant young princess found herself ignored and unwanted. Bewildered by dusty protocol and regarded as a necessary evil by her husband, Sophia Dorothea grew lonely as he gallivanted with his mistress under her nose. When Sophia Dorothea plunged headlong into a passionate and dangerous affair with Count Phillip Christoph von K nigsmarck, the stage was set for disaster. This dashing soldier was as celebrated for his looks as his bravery, and when he and Sophia Dorothea fell in love, they were dicing with death. Watched by a scheming and manipulative countess who had ambitions of her own, it was only a matter of time before scandal gripped the House of Hanover and tore the marriage of the heir to the British throne and his unhappy wife apart. Divorced and disgraced, Sophia Dorothea was locked away in a gilded cage for 30 years, whilst her lover faced an even darker fate. The story of Sophia:Mother of Kings haunted George I to his dying day.

Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan

Paperback – 29 May 2020 (UK) & 28 April 2020 (US)

In 1611, thirty-four-year-old Nur Jahan, daughter of a Persian noble and widow of a subversive official, became the twentieth and favourite wife of the Emperor Jahangir who ruled the Mughal Empire. An astute politician as well as a devoted partner, she issued imperial orders; coins of the realm bore her name. When Jahangir was imprisoned by a rebellious nobleman, the Empress led troops into battle and rescued him. The only woman to acquire the stature of empress in her male-dominated world, Nur was also a talented dress designer and innovative architect whose work inspired her stepson’s Taj Mahal. Nur’s confident assertion of talent and power is revelatory; it far exceeded the authority of her female contemporaries, including Elizabeth I. Here, she finally receives her due in a deeply researched and evocative biography.

The Crown in Focus: Two Centuries of Royal Photography

Hardcover – 15 May 2020 (UK & US)

The Crown in Focus traces the remarkable relationship between the British Royal Family and photography over the course of nearly 200 years, from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s enthusiastic adoption of the emerging technology in the mid-19th century to the use of Instagram by the modern monarchy. Today, photographs of the British Royal Family remain some of the most widely distributed images across the world. Featuring iconic formal portraits alongside little-known pictures from private collections, this fascinating book explores how each new development of the medium has been embraced to record royal life. Since its invention almost two centuries ago, photography has created an unprecedented intimacy between monarch and subject. Where previously royal painted portraiture allowed a degree of control and an element of creative licence and negotiation between artist and sitter, the development of the photographic image provided the public with a more personal window on to the lives of the people behind the pageantry. Over the years, the medium has helped to shape the role and purpose of the Royal Family – to the point where, in a rapidly changing society, the close connection between Crown and camera has ensured the continued survival and popularity of the British monarchy.

The Crown Dissected: An Analysis of the Netflix Series the Crown Seasons 1, 2 and 3

Paperback – 1 May 2020 (UK) & 7 February 2020 (US)

The Crown is one of North America’s favorite series. Hugo Vickers, however, has something to say about the popular series’ accuracy. All three seasons of it.

Called “the most knowledgeable royal biographer on the planet,” particularly on the period the series covers, Vickers has commented on the British Royal Family on television and radio since 1973, authored numerous books about the Royals, and acted as historical adviser on a number of films.

In his previous books on seasons one and two of The Crown, Vickers separated fact from fiction to tell readers what really happened and what certainly did not happen. Now adding the most recent season, The Crown Dissected: Seasons 1, 2 and 3 features Vickers’ same episode-by-episode approach analyzing the plot, characterization and historical detail in each storyline. He describes how the series continues to distort the facts, and refers back to previous seasons whenever needed.

Vickers writes that he does not approve of The Crown because “it depicts real life people in situations which are partly true and partly false, and unfortunately most viewers take it all as gospel truth.” He accepts that fiction can be a device to illuminate true events, but artistic license can create false, dangerous and lasting impressions as well what he calls a “perversion of what is true.”

Undoubtedly there will continue to be debate on the accuracy of The Crown‘s storylines, but that is what makes historical dramas so compelling. The Crown Dissected: Seasons 1, 2 and 3 is a must-read for any fan of the show, as well as for all TV critics.

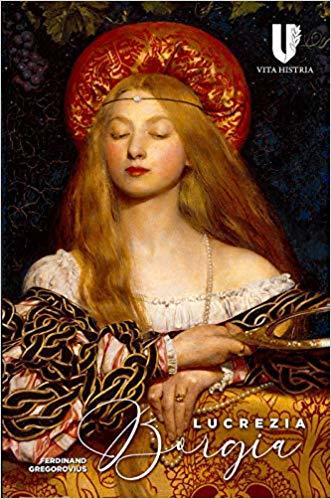

Lucrezia Borgia: Daughter of Pope Alexander VI (Vita Histria)

Hardcover – 1 May 2020 (UK) & 2 June 2020 (US)

Lucrezia Borgia is among the most fascinating and controversial personalities of the Renaissance. The daughter of Pope Alexander VI, she was intensely involved in the political life of Italy during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. While her marriage alliances helped advance the political objectives of the papacy, she also held the office of Governor of Spoleto, a role normally reserved for Cardinals, making her one of the most powerful and dynamic female figures of the Renaissance. Among the first books to employ historical method to move beyond myth and romance that had obscured the fascinating story of Lucrezia Borgia was the biography written by the noted German historian Ferdinand Gregorovius. Ferdinand Gregorovius (1821-1891) was one of the preeminent scholars of the Italian Renaissance. His biography of Lucrezia Borgia reveals the atmosphere of the Renaissance, painting a portrait of Lucrezia and her relationships with her father Rodrigo Borgia, Pope Alexander VI, her brother Cesare, her mother Vanozza, her father’s mistress, Giulia Farnese, her husband Duke Alfonso D’Este of Ferrara, and many others, including important artists and writers of the time. All are vividly portrayed against the colorful background of Renaissance Italy. Gregorovius separates myth from documented fact and his book remains a key reference work on the life and times of the Borgia princess.

The post Book News May 2020 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 16, 2020

Saleha – Queen of Brunei

The future Queen Saleha of Brunei was born as Hajah Saleha binti Haji Mohamed Alam as the daughter of Pengiran Anak Mohammad Alam and Pengiran Anak Hajah Besar – Pengiran being a hereditary title for those who are related by blood to the Royal family. Saleha’s grandfather was the younger brother of the 26th Sultan of Brunei. Saleha was born on 7 October 1946 in Brunei Town, now known as Bandar Seri Begawan – the capital city of the Sultanate of Brunei.

Embed from Getty Images

On 28 July 1965, Saleha married Pengiran Muda Mahkota (Crown Prince) Hassanal Bolkiah, who was also her paternal first cousin. Her father-in-law abdicated on 5 October 1967 and her husband became the 29th Sultan of Brunei and she the Raja Isteri (or queen consort) of Brunei. Saleha and her husband have two sons and four daughters: Princess Rashidah (born 26 July 1969), Princess Muta-Wakkilah (born 12 October 1971), Crown Prince Al-Muhtadee Billah (born 17 February 1974), Princess Majeedah (born 16 March 1976), Princess Hafizah (born 12 March 1980) and Prince Abdul Malik (born 30 June 1983). Saleha also has 17 grandchildren.

Embed from Getty Images

Her husband was also married to Azrinaz Mazhar from 2005 until their divorce in 2010. They have two children together. He was also married to Hajah Mariam between 1982 and their divorce in 2003. They had four children together. Her husband is currently the second-longest reigning current monarch after Queen Elizabeth II.

Embed from Getty Images

Saleha is the Patron to various organisations including the Women’s Institute, the Girl Guides Association of Brunei Darussalam, the Brunei Government Senior Officers Wives Welfare Association, the Women’s Council of Brunei Darussalam, The Women Graduates’ Association, and the Brunei Shell Women Association.

The post Saleha – Queen of Brunei appeared first on History of Royal Women.