Mark T. Conard's Blog, page 4

December 7, 2014

Committed: Writing as Life, Part I: History

I chose “writing as life” as the title for this series because if you’re truly a writer, the work becomes your life. It’s clichéd but true: You write because you have to. It’s a compulsion, a need deep down inside. If you do it—that is, put words together, tell stories, work with language, try to express and evoke thought and emotion with a narrative—if you do it, I say, for any other reason, you’re not a writer in the sense I’m talking about.

I’m by nature an introspective person—I dwell, ruminate, contemplate, obsess. This is part of the reason why I chose philosophy as my vocation; and the philosophical life is one that fosters and develops introspection. To put it plainly, I live a lot in my head, and thus it was natural that I became a writer—not merely of academic works, but also of fiction. But living so much in my own head means that it’s difficult to transition back to expressing ideas, thoughts, emotions externally, orally. Communicating with others verbally is difficult for me. The introspective life strains relationships, makes it difficult to live with others. That’s why the writing life is a commitment and a sacrifice.

Since 1998 or -99, when I began writing fiction, I’ve completed ten novels and done a major revision of four of them. I recently, within the last couple of years, went through two revolutions in my writing: the first epiphany was a new understanding of the nature and structure of story itself; in the second revolution I discovered how to integrate my philosophical interests with my fiction writing.

The writing life is full of rejection. I’ve had countless numbers of rejection letters and emails from agents and publishers. But the best response to rejection is to keep writing, keep getting better. Check that—it’s not the best response; it’s the only response.

History

Writing suspense fiction happened accidentally for me. I had a friend and drinking buddy when I was in grad school. He told me he was working on a screenplay, and I was intrigued by that idea, so we decided to work on one together and started kicking around some ideas. We didn’t have any particular genre in mind, but a story developed over many drinks, and finally we came up with a plot outline for a mystery/suspense story. He left it to me to turn into a screenplay, which I didn’t know how to do, so I set it aside.

One summer, several years later, I took out the notes and started writing the story as a novel (since I at least knew what a novel was supposed to look like). I hadn’t read any crime or suspense fiction before that, so I started reading in the genre. That was my introduction to authors who became my major influences: Elmore Leonard, Jim Thompson, Raymond Chandler, James Ellroy, and David Goodis. I developed the outline for the story, figured out the characters, wrote and rewrote, and finally I finished it. I enjoyed the process so much that I started a second one right away and have continued ever since.

After Dark, My Sweet by Jim Thompson, a big influence.

With the first novels I wrote, I was consciously mimicking those authors. I wrote an Elmore Leonard novel, a Jim Thompson novel, a James Ellroy novel, etc. It was when I was writing my 6th novel, originally entitled I Hate Sinatra, that I started to find my own voice. The writing began to sound like me. That was some eight years into the process, and it took a few more years to really hone in on that voice. It’s a never ending process, of course, and as I said above, I subsequently went through a couple of revolutions in my writing, and I’ll discuss those in future posts.

Killer’s Coda

My first novel, the one based on the screenplay ideas, I called The Big Picture, which is a terrible title, I know. It’s the story of a psychologist, Henry Blackwell, who does criminal profiling for the Philly PD. Blackwell’s wife was murdered prior to opening of the story, and the case was never solved. Blackwell has in the meantime become an alcoholic and suffers blackouts. At the opening of the story, a young woman is murdered and there are definite similarities between this crime and the murder of Blackwell’s wife. Further, Blackwell was acquainted with the victim. For Blackwell, this is the break he’s been waiting for, a fresh set of clues to help lead the police to his wife’s killer.

But it turns out that the killer was only just getting started. Other young women Blackwell knows also become victims. The detectives, Slomann and Busch, have a serial killer on their hands, and the evidence starts to point back to Blackwell himself. In a subplot, Blackwell becomes involved with a younger woman, an intrepid reporter, who’s hot to make a name for herself by telling Blackwell’s story. Blackwell begins to spiral out of control, and the women in his life—the reporter and Blackwell’s daughter—become potential targets for the murderer.

Killer’s Coda

The first draft of the novel was crap, of course. But the story was good, so I did a major revision of the novel in 2010, eleven or twelve years after I completed the first draft. That revision was re-titled, Blackwell’s Coda. I did a subsequent revision of it in 2013, when I had the opportunity to publish it as an e-novel. The published version, then, became Killer’s Coda.

An Active Protagonist

I intend to use the posts in this series to offer some things I’ve learned about writing along the way. Here’s the first one. In the first two drafts of what became Killer’s Coda, a lot of things happened to Henry Blackwell. There would be no story if nothing happened of course, but in those drafts, especially the first one, the climax and resolution of the plot occurred through the agency of other characters for the most part.

What I came to learn, and what now seems obvious, is that the protagonist of the story needs to be active. He or she must be the one who makes things happen in the end. Life, and thus story, is about struggle. A novel is about the struggle of the protagonist against forces that are either internal or external, or both. For good or ill, that is, whether you have an up or a down ending, the protagonist must be the agent of change, else the story is unsatisfying and the reader unhappy.

Excerpt

The first few lines of Killer’s Coda:

“I once took a shit at the Van Gogh museum,” said Henry Blackwell, as he toyed with a stack of crime scene photos laying on the bar.

“Yeah?” said the blond sitting next to him. “Where’s that?”

“Amsterdam,” he said.

“That’s in Europe, right?”

“Precisely,” he said. “It was a nice facility, very clean, no smell. It was obvious they maintained it with great diligence, which is characteristic of the Dutch, and they’d stocked it with soft, double-ply toilet roll. Very impressive. Much different than most public toilets you see around the world. You might not believe it, but some of the oldest, most respected restaurants in Paris offer you a simple hole in the floor for your convenience.”

“That doesn’t sound very nice.”

“It’s not, trust me.”

“I always wanted to go to Paris,” she said. “Is it as beautiful as it looks in the movies?”

Henry looked up and waved to the bartender. “What’s that guy’s name?”

“Charlie,” she said. “What’s in the pictures?” She came close to spilling her gin and tonic, leaning towards him to have a look. The photos contained unimaginative shots of the intimacies of brutal violation and death. Bruising covered the victim’s face and upper torso, blood speckled the flooring around her head, strangulation marks striped her neck.

“Hey, Charlie,” said Henry, waving his glass. “I need a refill.”

The bartender grabbed a bottle of Scotch from the shelf. “You should slow down on these,” he said, as he poured the whiskey.

“On the contrary,” said Henry. “I haven’t imbibed nearly enough. Can’t you leave the bottle?”

“You already asked me that, and the answer’s still no.”

“I thought you might’ve changed your mind.”

“What’s ‘imbibed’ mean?” said the blond.

“You should keep in mind,” said the bartender, “we’re not allowed to serve people who are visibly drunk.”

“Do I look drunk to you?”

Charlie raised his eyebrows. “No, I guess not,” he said. “But you’ve already had seven of those.”

“And I drank a pint before I got here.”

“Jesus, why aren’t you falling off the stool?”

“I have good balance,” said Henry.

The bartender walked away, shaking his head.

Henry wrote half a sentence in the notebook accompanying the photos and glanced around the somber West Philly tavern, a joint no one would call cool. A handful of kids from Penn occupied one of the tables. Henry pegged most of the other patrons as blue collar workers. They drank Budweiser or Yuengling, some of them wearing Eagles caps. Eric Clapton issued from the juke box, and rushes of cool air swept through the room whenever anyone entered or left.

“Haven’t I seen you in here before?” said the blond.

“Not for a while,” said Henry. He gulped the Scotch. “Normally I drink at home, but it’s a special occasion.”

“Oh, yeah? What’re you celebrating?”

“It’s eighteen months to the day since I lost everything,” he said.

She frowned. “You mean like on Wall Street?”

He stuffed the photos inside the notebook and wrapped a heavy rubber band around it. “Something like that.”

“You must be feeling real down,” she said. “I was wondering why you were drinking so much.”

“Yeah?” he said. He turned towards her, in a safe place now, gliding on top of the alcohol. “I was wondering why you don’t drink more.”

“What do you mean?” she said.

“Your makeup is meant to cover the bruising around your eye,” he said. “There’s a cigarette burn on your wrist, and your jaw is slightly misshapen on the right side—indicating that it’s been broken but not set properly, likely due to a lack of adequate medical treatment. Add that to the insecurities obvious in the way you speak and the questions you’ve been persistently asking since I sat down, and the fact that you’re seeking refuge in this place, looking for some stranger to give you comfort, tells me you’re in an abusive relationship. Your husband beats the shit out of you, doesn’t he?”

She stared at him and nodded her head.

“Don’t stay in that relationship,” he said. “Leave him before he kills you.”

“Okay,” she said, still staring at him.

“There are plenty of shelters in the city for victims of abuse. Find one in the phone book. They’ll have counselors who can help you.” Henry gathered his things and slipped on his jacket. The notebook fit into his pocket. “Nice talking to you,” he said.

“You too,” she managed to say.

[contact-form]

November 23, 2014

Shakespeare, Bitches! Volume II

On Twitter I post a daily quote from Shakespeare with a small addition: the word “bitches” at the end. This is my second installment of these. Click here to read the first one. Enjoy!

Shakespeare, Bitches!

“I’ll tickle your catastrophe, bitches.”

“I do desire we may be better strangers, bitches.”

“I am slain by a fair cruel maid, bitches.”

“Nothing emboldens sin so much as mercy, bitches.”

Poor Ophelia

“They are all but stomachs, and we all but food, bitches.”

“Let there be gall enough in thy ink, bitches.”

“My heart is true as steel, bitches.”

“In time the savage bull doth bear the yoke, bitches.”

“Put thyself into the trick of singularity, bitches.”

“Every Jack-slave hath his belly-full of fighting, bitches.”

“Golden lads and girls all must, As chimney-sweepers, come to dust, bitches.”

“I’ll make death love me, bitches.”

“The why is plain as way to parish church, bitches.”

Bill!

“I say there is no darkness but ignorance, bitches.”

“Men’s vows are women’s traitors, bitches!”

“Is it not strange that desire should so many years outlive performance, bitches?”

“He that is giddy thinks the world turns round, bitches.”

“There’s place and means for every man alive, bitches.”

“By that sin fell the angels, bitches.”

[contact-form]

“So foul and fair a day I have not seen, bitches.”

November 16, 2014

How We Got Duped into Believing Computers Can Think

I recently wrote a post, “Has A.I. Really Arrived?” in which I disputed claims that computers can or will think (click here to read the original post). In that essay I wasn’t articulating anything original. I was repeating the arguments of the philosopher John Searle.

Searle calls the idea that programs are to computers as minds are to brains “Strong A.I.,” and he argues—to my mind, successfully—that computers aren’t the sorts of things that can think. In brief, he argues that computers have syntax, i.e., they follow rules; but they don’t have semantics: In the information processing they do, there is no meaning or understanding, and these latter are essential to thought.

In this post, I want to address the issue of why we would ever believe that computers could think in the first place.

Thinking is a Natural Process

Let’s note that no one is hot to claim that machines generally, or computers specifically, can digest an apple, pass gas, have a bowel movement, or take a leak. But many people in various disciplines are falling over themselves to try to prove that computers can and do, or will, think. But why is that?

One reason is that computers do something that looks like thinking, namely information processing. That is, they take in data as an input, process it according to their programs, and then provide an output. There’s a strong temptation to look at the way our minds work in the same way: our senses provide the data that the mind processes, and then the mind spurs some sort of an action as a behavioral output. (E.g., I hear you ask me to pass the butter. My mind processes that information—I understand the sentence. And then I react: I pass the butter to you.)

But we shouldn’t make too much of this comparison. First, as I noted above, Searle well argues that the kind of information processing that computers do involves following rules (it’s syntactical) but involves no understanding of the content of what’s being processed (there’s no semantics or meaning). Whereas our thought—in using language, for example—essentially involves meaning.

Searle’s The Rediscovery of the Mind

Second, as Searle also notes in a particularly apt phrase, “Simulation by itself never constitutes duplication.” That is, computers can simulate certain mental activities, but that by itself never amounts to duplication, actually thinking. As he notes in one of his examples, my computer can also simulate a rainstorm, but I don’t get wet from it.

But the reasons why we have a strong urge to believe that computers can think are much deeper, older, and more complex than this.

Before I get to that, though, consider this: thinking is a biological activity—something that living creatures do—no different in that regard from eating, digesting, farting, peeing, or having bowel movements. No different. It’s a completely natural process. (And it’s not specifically human, of course. Cats, dogs, monkeys, chickens, dolphins, etc., all do it.)

Two Tendencies

There are two tendencies that human beings have been prone to since the time of the ancients, which indicates that those proclivities are quite deep-seated, if not hardwired.

The first is anthropomorphization: We have a strong tendency to treat non-human entities as if they had human characteristics. This is evident in the way that people tend to attribute thoughts and feelings to their pets that the pets aren’t capable of having. We also do it in offhand ways when we say things like, “the plant is thirsty,” when we just means it needs to be watered; or “my computer hates me,” when it’s not functioning well.

This tendency seems to be a particular version of our need to make the unfamiliar and frightening into something familiar, understandable and thus less scary. The ancients clearly did this in personifying natural phenomena, or seeing them as the work of the fickle gods.

Great Zeus

Our desire to endow our computers with the human capacity for thought (and to make Siri speak to us in a human voice, e.g.,) is another example of this tendency.

The second, and perhaps more important, tendency in our history is our strong propensity to think of ourselves as different from the rest of nature, somehow more noble, somehow elevated above nature.

Plato was one of the first to formalize this as philosophical doctrine. He has Socrates argue in the Phaedo that the body is a prison for the soul or mind, which will live on and perhaps be reincarnated after we die. Christianity, in part influenced by Plato, promulgated the idea of personal immortality. Again, the soul is something distinct from our material bodies, and after the body dies and decays, the soul will live on somehow.

One reason for all this is our fear of death, of course, but another important reason is that the part of us that distinguishes us from other kinds of animals—our gigantic brains and our ability for complex and abstract thought— is the part of us that we have the most difficult time understanding as natural. Consequently, we think of it as non-physical, non-material, something otherworldly that must be separate from our physical bodies. (Click here to read my post regarding the difficulty of the problem of consciousness.)

A great example of this is Descartes and his metaphysical dualism (and we shouldn’t forget that Descartes was a Christian). The body is an extended thing, says Descartes, something material existing in space; and the mind is a completely different substance. It’s non-physical, aspatial, etc., such that it’s not subject to the same alterations and corruption as the body.

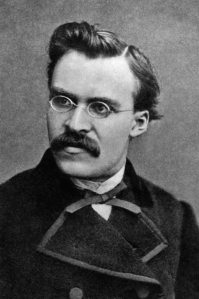

It took revolutionary philosophers like Hume, and then following him Nietzsche, to convince us of something we tried so desperately to deny: we’re animals, and as such we’re a part of nature. Both Hume and Nietzsche (as well as a number of other great thinkers) devoted themselves to the project of re-integrating humanity into nature, to shedding the antiquated idea of ourselves as somehow different, and to understanding ourselves in completely naturalistic terms.

David Hume

The project of Strong AI is one of the last vestiges of metaphysical dualism; it’s akin to the religious belief that thinking is somehow non-natural, somehow not connected to our animal natures, something distinct from the functioning of our bodies, such that something else that functioned completely differently—something inorganic [!], in fact—could think.

The next time someone says computers can think, ask him or her if they can also pee and poop and digest food. When he scoffs, tell him that thinking, like all those things, is a naturally functioning process of organic bodies.

[contact-form]

November 10, 2014

Inspirational Quotes and Shit Volume IV

I went on a mission a while back on Twitter to try to expose just how banal inspirational quotes are. My most successful effort was to add “and shit” to the end of traditional quotations.

E.g., “I hate quotations. Tell me what you know, and shit.” (Emerson)

In no way did this motivate people to stop and think about the banality of what they were doing in posting quotes, but it was a lot of fun.

So I’ve put together a fourth partial list of the “and shit” quotes that I’ve posted on Twitter. (Click here for the first list, here for the second, and here for the third.)

I always add a comma before the “and shit” to mark the end of the actual quote, whether that comma is actually needed or not.

Enjoy!

AND SHIT!

“In all chaos there is a cosmos, in all disorder a secret order, and shit.” (Jung)

“Great love affairs start with Champagne and end with tisane, and shit.” (Balzac)

“A chain is no stronger than its weakest link, and life is after all a chain, and shit.” (William James)

“There is no sincerer love than the love of food, and shit.” (G.B. Shaw)

“Where there is injury let me sow pardon, and shit.”

Francis of Assisi

“A woman’s whole life is a history of the affections, and shit.” (Washington Irving)

“Well married a person has wings, poorly married shackles, and shit.” (Henry Ward Beecher)

“He was a bold man that first ate an oyster, and shit.” (Jonathan Swift)

“Love is often the fruit of marriage, and shit.” (Moliere)

“One is best punished for one’s virtues, and shit.” (Nietzsche)

“Good things happen to those who hustle, and shit.”

Anais Nin

“It is by acts and not by ideas that people live, and shit.” (Anatole France)

“Faith is a passionate intuition, and shit.” (William Wordsworth)

“What is to give light must endure burning, and shit.” (Viktor E. Frankl)

“I like honesty and fair play, and shit.” (Marcus Garvey)

“When in doubt tell the truth, and shit.” (Twain).

“Easy reading is damn hard writing, and shit.”

Hawthorne

“Suffrage is the pivotal right, and shit.” (Susan B. Anthony)

“Evil is whatever distracts, and shit.” (Kafka)

“Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom, and shit.” (Kierkegaard)

“Who questions much, shall learn much, and retain much, and shit.” (Francis Bacon)

“All wealth is the product of labor, and shit.” (John Locke)

“A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence, and shit.”

David Hume

“Words are the money of fools, and shit.” (Thomas Hobbes)

“There is no doubt the eye was intended for us to see with, and shit.” (Joseph Butler)

“Nothing can make you more humble than pain, and shit.” (Larry Flynt)

“Children are our most valuable natural resource, and shit.” (Herbert Hoover)

“By doubting we are led to question, by questioning we arrive at the truth, and shit.” (Peter Abelard)

“Growth is the only evidence of life, and shit.” (John Henry Newman)

“Life seems but a quick succession of busy nothings, and shit.”

Jane Austen

“Life grants nothing to us mortals without hard work, and shit.” (Horace)

“The purpose of life is to be defeated by greater and greater things, and shit.” (Rainer Maria Rilke)

“The best part of beauty is that which no picture can express, and shit.” (Francis Bacon)

“Poetry is the synthesis of hyacinths and biscuits, and shit.” (Carl Sandburg)

“For the signifier is a unit in its very uniqueness, being by nature symbol only of an absence, and shit.” (Lacan)

“Heaven help the American-born boy with a talent for ballet, and shit.” (Camille Paglia)

“I put myself in the hands of Christ, who is the true leader of the church, and shit.” (Pope Theodoros II)

[contact-form]

November 2, 2014

Has A.I. Really Arrived?

In a recent article in Wired magazine, “The Three Breakthroughs That Have Finally Unleashed AI on the World,” the author, Kevin Kelly, claims that artificial intelligence (AI) is here and here to stay. He understands AI, apparently, as machine (specifically, computer) intelligence that will become more and more a part of our lives. He claims this final step in computer evolution has been made possible by three developments: Cheap parallel computation, big data, and better algorithms. I won’t go into the details of Kelly’s article, but let me just note that Kelly believes that computers are or will be intelligent and conscious:

“As AIs develop, we might have to engineer ways to prevent consciousness in them—and our most premium AI services will likely be advertised as consciousness-free.”

He goes on to claim, rather dramatically:

“But we haven’t just been redefining what we mean by AI—we’ve been redefining what it means to be human. Over the past 60 years, as mechanical processes have replicated behaviors and talents we thought were unique to humans, we’ve had to change our minds about what sets us apart. As we invent more species of AI, we will be forced to surrender more of what is supposedly unique about humans. We’ll spend the next decade—indeed, perhaps the next century—in a permanent identity crisis, constantly asking ourselves what humans are for…The greatest benefit of the arrival of artificial intelligence is that AIs will help define humanity. We need AIs to tell us who we are.”

Hello, Dave…

Computers are information processing systems: they take in information, process it, and provide an output; and as technology has developed, they’ve been able to do this faster and faster, accessing larger and larger data bases, while taking up less and less space. What’s more, one way of looking at and understanding the human mind is to see it similarly as an information processing system: we take in information in the form of, say, sense perception, process it, and provide an output. (I see a piece of pie, realize that I’m hungry and that I love pie, and consequently I grab a fork.)

So the big question, since the dawn of the computer age, has been: do computers and minds work the same way? Can computers think in the way that we do? Thinking is a conscious mental process, a matter of having subjective mental states. Consciousness is awareness of the environment and of one’s own thoughts, feelings, etc. (See my earlier post, “When Science Gets Stupid” for more discussion of consciousness itself.)

Can computers have these kinds of mental states?

Can Computers Think?

The answer to the question is no. Computers can’t think, they don’t have mental states, and they will never become conscious. I will draw upon (report, really) the work of the philosopher John Searle to provide the justification for this answer.

In his essay, “Can Computers Think?” in Minds, Brains, and Science, Searle identifies Kelly’s position as “Strong AI,” which is the idea that the mind is to the brain as the computer program is to the computer. Searle says:

“This view has the consequence that there is nothing essentially biological about the human mind. The brain just happens to be one of an indefinitely large number of different kinds of hardware computers that could sustain the programs which make up human intelligence. On this view, any physical system whatever that had the right program with the right inputs and outputs would have a mind in exactly the same sense that you and I have minds. So, for example, if you made a computer out of old beer cans and powered by windmills; if it had the right program, it would have to have a mind.”

This is a mistake, argues Searle. Thinking is a biological process, something that living creatures like ourselves do, no different in that regard from digestion. That is, thinking arises out of the natural, organic process of brain functioning, so the biology and composition of the thing that thinks is of great importance: it’s what makes thinking possible at all.

Minds, Brains, and Science

As Searle puts it so aptly, “simulation by itself never constitutes duplication.” In other words, computers—given what they are—can simulate certain features of human cognition; but that doesn’t mean that the computers are duplicating human thought. Or, to put it another way, that Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov in chess doesn’t prove that Deep Blue has a mind; it only proves that you don’t need a mind to win at chess.

To demonstrate his point, Searle came up with his Chinese Room thought experiment. Imagine, he says, he’s in a room, and someone puts cards with Chinese characters on them through a slot. Searle doesn’t understand any Chinese at all (which is why he chose that particular language). His task then is to take that character and look up in a book of rules the proper character that corresponds to it. When he has that second character, he then feeds it back through the slot. So, in other words, the Chinese room works just like a computer: there is data input, a set of rules governing the processing of the data, and an informational output.

But here’s the kicker: Searle still has no understanding of the language or the characters whatsoever. Or, as he puts it, computers have syntax (they follow rules), but they have no semantics, which is meaning. But semantics, meaning, is essential to thought; that’s what thought essentially is. He says:

“The whole point of the parable of the Chinese room is to remind us of a fact that we knew all along. Understanding a language, or indeed, having mental states at all, involves more than just having a bunch of formal symbols. It involves having an interpretation, or a meaning attached to those symbols. And a digital computer, as defined, cannot have more than just formal symbols because the operation of the computer…is defined in terms of its ability to implement programs. And these programs are purely formally specifiable—that is, they have no semantic content.”

The Rediscovery of the Mind

(I’ll note in passing that in a later work, The Rediscovery of the Mind, Searle goes on to argue that computers don’t even have syntax: “The ascription of syntactical properties is always relative to an agent or observer who treats certain physical phenomena as syntactical.” Or, in other words, because syntax isn’t a natural feature of things like mass is (for example), anything can be described as if it were following rules: water running downhill, or the pen simply laying on the table. Consequently, that something is following rules (having a syntax) can only be specified from a third-person point of view, from the position of an observer. Thus, syntax isn’t even inherent to computer operations.)

Thinking is a Biological Process

None of this is to say that computers aren’t powerful and life-transforming for humans; it’s not to say that they haven’t and won’t continue to dominate more and more of our lives. All that is true. No, Searle’s point is that it’s a mistake to call what computers do thinking, and to say that computers don’t and can‘t, and never will, have mental states. Again, having mental states is a perfectly natural, biological function of certain kinds of creatures like ourselves.

Curiously, in “Can Computers Think?” Searle argues that it might in principle be possible to create something artificial that could in fact think; but whatever that would be, it wouldn’t be a computer, since it would have to have the causal powers of the brain. I say this is curious, because it conflicts with his, to my mind, crucial point that thinking is a biological function like digestion. In the essay, though, he doesn’t address this conflict.

In conclusion, I agree that we’re constantly trying to figure out what it means to be human, but this is part of the human condition, and not, as Kelly would have it, because computers can think. We don’t in fact need A.I. to tell us who we are; and it couldn’t even if we wanted it to.

http://www.wired.com/2014/10/future-of-artificial-intelligence/.

Searle, Minds, Brains, and Science, 28.

Searle, Minds, Brains, and Science, 37.

Searle, Minds, Brains, and Science, 33.

Searle, The Rediscovery of the Mind, 208.

[contact-form]

October 26, 2014

The Good, The Bad, and Schopenhauer

Last week I gave a paper at the Society for Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy meeting in New Orleans. It was on Nietzsche’ view of pessimism, so I thought I’d take the opportunity to talk a bit about the philosophical conceptions of optimism and pessimism.

Both optimism and pessimism are generally understood as involving an evaluation of life, whether it’s worth living or not; and that evaluation is typically tied to the experience of pleasure and suffering. That is, optimists weigh the pleasure that we can and often do experience in life against the pain and suffering that we endure and judge that, on the whole, pleasure generally predominates, such that the whole business is typically worth it. Pessimists, in contrast, judge that there’s more suffering than pleasure, and so life isn’t worthwhile.

Is life really worth it?!

Arthur Schopenhauer, a 19th Century philosopher, was a thoroughgoing pessimist. For him, life is essentially the struggle and striving of the drives and instincts within us, which he collectively calls “the will.” The will meets resistance in its efforts to find satisfaction, and that resistance causes pain and suffering (you want something, try to get it, something stands in your way, and that causes you to be unhappy). That state of dissatisfaction and its attendant pain is our common lot in life. We desire, and so we suffer. Any satisfaction of our desire is nothing positive; it’s merely a release from our temporary suffering. Further, any long term satisfaction soon turns to boredom. As Schopenhauer says in “On the Vanity and Suffering of Life”:

“…we have not to be pleased but rather sorry about the existence of the world; its non-existence would be preferable to its existence…”

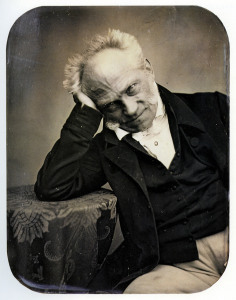

Schopenhauer

A more extreme form of optimism was articulated by the early modern philosopher, Leibniz, who claimed that this is the “best of all possible worlds.” That’s a stark claim and for most of us, I assume, it seems like a real stretch of the imagination. Couldn’t the world be better than it is, if we, say, removed certain sources of unnecessary pain and added more sources of pleasure and happiness? According to Leibniz, no. He was compelled to adopt this idea because he was a theist, and he thought it impossible that God could’ve created a world that was less than absolutely perfect.

Voltaire makes merciless fun of this idea in Candide. The title character is persuaded to the Leibnizian view of things, but then witnesses a series of horrendous misfortunes, after each one of which he declares everything must be for the good, since this is the best of all possible worlds. The innocent Candide learns this theory from his teacher, Dr. Pangloss. Sometime after the latter’s apparent demise, Candide tells someone:

“A wise man, who later had the misfortune to be hanged, taught me that such things are exactly as they should be.”

Voltaire

Then, later, when he’s improbably reunited with Pangloss, Candide asks him whether he still maintains his optimism:

“Tell me, my dear Pangloss,” said Candide, “when you were hanged, dissected, cruelly beaten and forced to row in a galley, did you still think that everything was for the best in this world?”

“I still hold my original opinions,” replied Pangloss, “because, after all, I’m a philosopher, and it wouldn’t be proper for me to recant, since Leibniz cannot be wrong, and since pre-established harmony is the most beautiful thing in the world.”

It’s a wonderful satire.

Further, in an essay called “On the Suffering of the World,” Schopenhauer argues that this doesn’t get God off the hook:

“Even if Leibniz’s contention, that this is the best of all possible worlds, were correct, that would not justify God in having created it. For he is the Creator not of the world only, but of possibility itself; and, therefore, he ought to have so ordered possibility as that it would admit of something better.”

Since God created not only the world, but possibility itself, he ought to have created a better possibility than this one. Schopenhauer in fact goes on to argue that, far from being perfect, this is the worst of all possible worlds. He “argues” in “On the Vanity and Suffering of Life,” that if the world were just a little worse, it wouldn’t be able to exist. It’s not a very good argument, but Schopenhauer’s thinking is so dark and pessimistic that it’s fun to read.

Leibniz

Leibniz’s theory falls under the category of “theodicy,” which literally means the justification of God, or the ways of God. The problem is that there are contradictions and incoherencies in the way that we like to think of the Western God. For example, there’s a conflict between God’s being omniscient (all-knowing) and our supposedly having free will, the liberty to make decisions and choose the actions we’ll take; since, if God knows everything, then presumably knows what you’re going to choose, in which case, how can you be free to choose it?

But theodicy typically refers to what’s known as the problem of evil. That is, there’s a conflict between God as omnipotent (all-powerful), omnibenevolent (all-good), and the creator of the world. If God is the creator and all-powerful, then why is there evil in the world? If he’s omnipotent, then surely he could have created the world such that there would be no evil. You might want to say that evil is a result of the actions of human beings. That’s all well and good, but nonetheless innocents suffer whether at the hands of other human beings or from natural causes. And surely the avoidable suffering of innocents is itself an evil (avoidable because God could’ve prevented it, but he didn’t).

So theists like Leibniz, who strain for consistency in their thinking, are put in the position that the terrible things that happen, even to innocents, must somehow be for the good. They must be, since God couldn’t and wouldn’t have created a world that was less than perfect.

The Man Himself.

FYI, Nietzsche thought that theories that measured the value of existence in terms of pleasure and pain, like optimism and pessimism, were misguided:

“Whether it is hedonism or pessimism, utilitarianism or eudaemonism—all these ways of thinking that measure the value of things in accordance with pleasure and pain, which are mere epiphenomena and wholly secondary, are ways of thinking that stay in the foreground and naïvetés on which everyone conscious of creative powers and an artistic conscience will look down not without derision, not without pity.”

Pleasure and pain are ultimately unimportant; they’re superficial, and thus philosophies such as optimism and pessimism, which measure the value of the world in accordance with pleasure and pain, are themselves superficial.

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, Vol. II, “On the Vanity and Suffering of Life,” trans. E.F.J. Payne (New York: Dover, 1969), p. 576.

Voltaire, Candide, trans. Lowell Bair (New York: Bantam Books, 1959), p. 87.

Ibid., p. 114.

Accessed via the web at: http://www.graycadence.com/OntheSufferingoftheWorld.pdf.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1966), p. 225 .

[contact-form]

October 19, 2014

Making Sense of Our Lives

In an essay in the Sunday New York Times entitled, “Does Everything Happen For a Reason?” Konika Banerjeee and Paul Bloom (a Yale graduate student and professor, both in Psychology) discuss studies showing that most people tend to find meaning and purpose in the events in their lives. One might think that this is tied to one’s religious beliefs, such that theists naturally believe in such meaning and purpose, whereas atheists don’t. But that’s not the case. Atheists as well as theists similarly seek and claim to find meaning and purpose in events. This implies that the tendencies is a deep-seated, natural inclination of human beings (hardwired, if you want to put it that way).

On the one hand, this makes good sense, given how radically incomplete our lives are because of our mortality. One of the most unsettling experiences one can have is to walk around the house of someone who has just died. What do you find? Shopping lists, bills on the table, food in the refrigerator, a half-read book on the sofa. Our lives simply end in death. They just stop. There’s no arc, no climax, no denouement. This is part of the reason we tell stories: we want the narratives of our lives to have a beginning, middle and end; and making up stories allows us to give a sense to things, and an ersatz arc to our lives. Thus we are by nature story-telling animals.

Further, as the authors of the essay note, we’re purposeful beings; we do things for a reason. We’re goal-directed throughout our lives. You study in school to get a degree, you get a degree to get a job and have a career, you have a career to…In other words, we perform actions that have ends or goals; and those ends or goals become the means to some further end. As the authors of the essay note, we then have the habit of projecting purposiveness onto nature. (And this may well be part of our deep-seated tendency to anthropomorphize, to treat nonhuman things as if they had human characteristics; and that is a way to render the strange and foreign familiar, to make it less scary.)

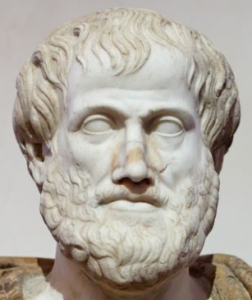

Aristotle

The idea that things have goals or purposes that they tend towards is known as “teleology,” and it was an important part of Aristotle’s thinking. In his ethics, Aristotle argues that, in addition to our everyday and long range goals, there is some final end that human beings aim at: happiness or flourishing. It’s what guides and makes sense of all our actions and decisions.

What’s more, Aristotle also believed that there was teleology in nature, that natural organisms and the parts of those organisms have ends that they serve: the eye is for seeing, the heart is for pumping blood, etc. For a long time, throughout the Middle Ages, this way of thinking dominated in the Western world. And it’s the source of one of the traditional arguments for God’s existence: the teleological argument.

The argument has its roots in Plato, and Thomas Aquinas offers a version of it. It’s often presented as an argument by analogy: Take an artifact, something someone has made, like a watch. We examine it and see the intelligent design. The watch didn’t happen to fall together accidentally. Someone created it in order to serve the purpose that it fulfills. You see the intelligent design, and so you must conclude that it had an intelligent designer. Similarly, examine elements in nature: Again, your eye, your heart, the roots of a plant. You see that they show intelligent design: they’re well-suited to doing what they do. Consequently, we must conclude that they had an intelligent designer, God.

(FYI, this wasn’t Aristotle’s argument; he thought things in nature just served their ends without having been designed.)

The argument doesn’t work. First, as evolutionary theory well shows, things can show design without having been designed: they can have evolved through natural selection over millions of years. [And the whole idea of teleology was abandoned with the early modern scientific revolution, btw; Aristotelian science gave way to the Newtonian.] Second, given all the inefficiencies and wastefulness of nature, it’s not even clear that the world actually shows design; or, to put it in a more snarky way, if the world was designed, the designer really botched the job. Third, as the great David Hume remarked, any universe would have to look as if it had been designed to some degree, whether it had been designed or not. If it’s parts didn’t fit together to some minimal degree, it couldn’t hold together as a universe.

Last, let me note that, while the research shows that our tendency to find meaning in events doesn’t follow from our religious beliefs, the opposite might in fact be the case: our religious beliefs might follow from our need to make sense of the events in our lives.

You knew I was going to reference Nietzsche here, didn’t you? Well, you were right.

On the Genealogy of Morals

Not only are our lives radically incomplete, as I noted above, they’re also full of pain and suffering. As Nietzsche notes, we’re very resilient creatures: we can put up with a great deal of struggle, suffering, and unhappiness in our lives—as long as that suffering has a meaning. That is, it’s not suffering per se that we find objectionable, but rather the meaninglessness of suffering:

“What really arouses indignation against suffering is not suffering as such but the senselessness of suffering: but neither for the Christian, who has interpreted a whole mysterious machinery of salvation into suffering, nor for the naïve man of more ancient times, who understood all suffering in relation to the spectator of it or the causer of it, was there any such thing as senseless suffering. So as to abolish hidden, undetected, unwitnessed suffering from the world and honestly to deny it, one was in the past virtually compelled to invent gods and genii of all the heights and depths, in short something that roams even in secret, hidden places, sees even in the dark, and will not easily let an interesting painful spectacle pass unnoticed.” (On the Genealogy of Morals, II, 7)

Nietzsche suggests that the origin of gods springs from our need for someone to bear witness to our suffering, in order precisely to give it meaning.

October 18, 2014

Discussion of “When Science Gets Stupid”

A blogger by the name of Janet Kwasniak took issue with my piece on consciousness, “When Science Gets Stupid,” which was a reaction to an essay in the New York Times, “Are We Really Conscious?” by Michael Graziano.

Kwasniak claims that I apparently didn’t understand Graziano’s piece, since I defined consciousness as awareness. Though she didn’t call the fallacy by name, presumably she’s saying I’m begging the question, because awareness is exactly what Graziano (and Dennett and Churchland) say consciousness can’t be.

If you’re interested, below is the comment I posted at Ms. Kwasniak’s blog, where I explain that I didn’t misunderstand Graziano’s piece nor beg the question.

As I suggest to Ms. Kwasniak, anyone who’s interested in an alternate and sensible account of the nature of consciousness and of the relationship between consciousness and the brain would do well to read John Searle. Searle doesn’t have the answer—there isn’t one yet—but he points us in a reasonable direction.

Ms. Kwasniak,

I didn’t misunderstand Graziano’s essay. I simply disagree with the way that he and Dennett and Churchland frame the issue. You seem to agree with them that neuro-physiology *must* be the solution to the problem of consciousness; that consciousness must be explained purely in physicalist terms.

My claim (and it’s not original to me; I’m simply reiterating the points that others have made) is that natural scientific methodology is by its very nature simply unsuitable to answer certain questions. Because that methodology is incapable of dealing properly with the issue of consciousness, researchers like Graziano and Dennett and Churchland tell us that consciousness can’t be what we think it is; it has to be something else that *is* explainable in physicalist terms. My conclusion is that any theories that contradict so thoroughly our own experience (of course we’re conscious!) reveal the inadequacy of natural scientific methodology in this case. Until the physical sciences are better equipped to handle the problem, it’s best approached philosophically.

To address a couple of your points:

In defining consciousness as “awareness,” I wasn’t misunderstanding the problem. I was providing a working definition, a sense of what I was talking about, to my non-specialist readers. My piece wasn’t an academic essay, and it wasn’t meant for specialists; it was directed at lay-people who might be interested in the subject. You may charge me with question-begging; but to my mind, any theory that tells us that we’re not aware (of things in the world, our own thoughts, feelings, memories, etc.) is crazy.

Second, I didn’t mean to insult Professor Graziano by saying “a guy named…” I was using a colloquial expression again for my non-specialist readers, who wouldn’t have heard of him.

Third, saying the problem should be handled philosophically isn’t a matter of pulling rank; it’s again to recognize the limits of natural scientific methodology in handling this particular problem.

I see that your sympathies lie with neuroscience and theorists like Graziano, Churchland, and Dennett. I was simply offering an alternate account of the issue (leaning on the work of John Searle—whom I would recommend to you), one that I think better accords with our experience.

Mark Conard

October 15, 2014

Narratives and Our Ways of Knowing Part II: The Middle Ages

I posted this several months ago. It’s the second in a series that I still mean to complete. So stay tuned.

Originally posted on Mark T. Conard:

Originally posted on Mark T. Conard:

The question of knowledge is a very old problem, going back to the ancients. What we can know about the world, and how we know it, is a huge puzzle. Now, we all love to tell stories, to tell people about things that have happened to us—or even stuff that happened to others, if it makes for a good tale. More than that, story-telling seems to be hardwired in us. We have a deep need to construct narratives to make sense out of the world and our lives. So not only do we try to convey what we think we know through our stories, but those stories also reflect the issues and problems regarding our ways of knowing.

I’m going to write a series of posts concerning the history of story-telling and our problems concerning the ways of knowing. I’ll move from Plato to Medieval Christianity, then to Descartes and…

View original 1,241 more words

October 13, 2014

When Science Gets Stupid

In the Weekend Review section of yesterday’s New York Times there appeared an essay called, “Are We Really Conscious?” with the tag line: “It sure seems like it. But brain science suggests we’re not.”

First, what do we mean by consciousness or being conscious? A good synonym is “awareness”: to be conscious is to be aware. It’s to have subjective mental states about one’s environment, and in that respect a great many creatures besides ourselves are conscious (the dog chases the cat and barks at the mailman, right?); further, it’s to be aware that one is aware–to be tuned into one’s own subjective mental states (to be aware of them as mental states). It was thought for a long time that humans are the only creatures with that sort of self-awareness, though there’s evidence that other higher-order animals have some form of it as well.

Consequently, the question, “Are we really conscious?” is a monumentally stupid thing to ask. Why? Because consciousness, awareness, is a precondition of asking, understanding, and attempting to answer the question. As language-users, as creative thinkers, as creatures capable of art, music, doing mathematics, dancing–hell, of telling and laughing at fart jokes–we have a very sophisticated and sensitive relationship to our environment. Our minds are extraordinary information-processing centers (and so much more!), taking in sensory data, processing it, and somehow spurring reactions in the form of behavior. All that essentially involves awareness–consciousness!

Check out the big brain on Brad!

Now, the problem of consciousness, how these magnificent brains of ours produce our conscious mental states, is so far a mystery, in fact one of the greatest mysteries and as-yet unsolved problems of science and philosophy. The human brain is a tremendously complex organ–one of, if not the, most complex things in the universe, with tens of billions of neurons firing to make up our experience of ourselves and the world.

There are many ways to try and approach the problem of consciousness, to answer the big problem. (One of the more sensible approaches to the problem–though there isn’t yet a solution!–is John Searle’s; check out his book, The Rediscovery of the Mind.)But who would suggest that we’re not conscious at all? The author of the Times essay is a guy named Michael Graziano, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Princeton, and in his essay he’s citing the work of Daniel Dennett and Patricia Churchland, two philosophers who work in this area. Their position is called “eliminativism,” because they propose to solve the big problem by simply eliminating consciousness altogether. This speaks to the magnitude of the mystery: People are so confounded by it, that they’re willing to come up with very complex theories saying frightfully stupid things to try to deal with it. Think about it. They’re literally saying you’re not aware, you’re not conscious. You don’t feel, believe, remember, daydream, fantasize, perceive, any of those things–those are all internal, subjective, conscious mental states, and according to Dennett and Churchland, they’re fictions. We don’t really have them in the way we think we do.

The Rediscovery of the Mind

Besides the great difficulty of the question of mind and consciousness, there are a couple of other problems with scientific methodology that are in play here.

First, science approaches problems from a third-person, objective viewpoint, and it considers any investigation that doesn’t take that approach as failing to live up to the standards and practices of science. The problem is that, as Searle puts it, consciousness has a first person ontology: it’s only accessible by the person who’s consciousness it is. It’s not accessible from a third person point of view. In other words, I can only think my own thoughts. You don’t have access to them. So consciousness falls outside the range of phenomena that can be investigated, as science has traditionally been understood. If we can’t examine it, study it, poke at it in a lab, it must not really exist.

Second, science has a very practical, and historically a very successful standard approach in describing and understanding phenomena at the everyday level, by looking at the components of those things at the micro-level. That is, we can predict a lot about everyday medium-sized objects by looking at their minute parts, their atoms and molecules (and even minuter parts than those). The problem is that this approach has been so successful that it’s become a kind of dogma that everything at the macro level is explained by the micro level; that everything just is atoms and molecules, and the even smaller bits. In other words, scientists (and philosophers of an ilk) confuse description with explanation. That is, when scientists are describing things at the micro level, they mistakenly believe they’re explaining those macro things as protons, neutrons, quarks, etc.

A third problem is the mathematization of nature by science. That is, in order to achieve it’s great predictive success, science wants to describe everything in mathematical terms. All objects of investigation have to be mathematically describable, and anything that can’t so be reduced is dismissed as unreal. Brains can be weighed and measured, but mind’s can’t, ergo…

Now, this is fine and causes no harm if you’re trying to understand why a table is solid, why water is wet, why people get sick from germs, why balls roll down inclined planks, and so forth. But when you’re trying to explain human experience, trying to capture, describe, explain the meaning of Shakespeare, or Beethoven, why you love chocolate ice cream, or any other complex human achievement, to say it’s really just molecules made up of atoms, which are really just empty space, which is all reducible to a few fundamental forces at the quantum level that can be measured and calculated mathematically…well, you’re getting silly again.

The Gay Science

As Nietzsche put it way back in the 1880s:

“A ‘scientific’ interpretation of the world, as you understand it, might therefore still be one of the most stupid of all possible interpretations of the world, meaning that it would be one of the poorest in meaning. This thought is intended for the ears and consciences of our mechanists who nowadays like to pass as philosophers and insist that mechanics is the doctrine of the first and last laws on which all existence must be based as on a ground floor. But an essentially mechanical world would be an essentially meaningless world. Assuming that one estimated the value of a piece of music according to how much of it could be counted, calculated, and expressed in formulas: how absurd would such a ‘scientific’ estimation of music be! What would one have comprehended, understood, grasped of it? Nothing, really nothing of what is ‘music’ in it!” (The Gay Science, 373)

Nietzsche is talking in the pre-20th Century language of mechanics, but we can easily update his sentiments with the contemporary talk of quantum physics, as I hinted above. With it’s methods, science is wonderful, helpful, generates real knowledge about the world; but it’s incapable of investigating lived human experience in all its richness and meaningfulness. That isn’t to say, mind you, that there is no reasoned approach to human experience, no arguments to be made, no evidence to examine. It’s only to say that we need a different methodology–that of Philosophy!