Mark T. Conard's Blog, page 5

October 6, 2014

Narratives and Our Ways of Knowing Part I: Plato’s Dialogues

I posted this several months ago. It’s the first in a series that I still mean to complete. So stay tuned.

Originally posted on Mark T. Conard:

Originally posted on Mark T. Conard:

Narratives and Our Ways of Knowing Part I: Plato’s Dialogues

The question of knowledge is a very old problem, going back to the ancients. What we can know about the world, and how we know it, is a huge puzzle. Now, we all love to tell stories, to tell people about things that have happened to us—or even stuff that happened to others, if it makes for a good tale. More than that, story-telling seems to be hardwired in us. We have a deep need to construct narratives to make sense out of the world and our lives. So not only do we try to convey what we think we know through our stories, but those stories also reflect the issues and problems regarding our ways of knowing.

I’m going to write a series of posts concerning the history of story-telling and our problems concerning the ways of knowing. I’ll…

View original 801 more words

September 28, 2014

Nietzsche and the Meaning and Definition of Noir

This essay originally appeared in my The Philosophy of Film Noir volume.

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) was adapted from a novel by the hard-boiled writer, James M. Cain. The movie is interspersed with voice-over narration by the protagonist, Frank Chambers (John Garfield), indicating that he is recalling events in the past. Frank is a drifter who takes a job at a remote diner, owned by an older man, Nick (Cecil Kellaway), after getting a look at Nick’s stunning young wife, Cora (Lana Turner). There is a strong sexual attraction between Frank and Cora, and, after one aborted attempt, they succeed in killing Nick and making it look like a car accident, in order to be together. A suspicious D.A., however, hounds them and finally tricks Frank into signing a statement claiming that Cora murdered Nick. Cora beats the rap, and the lovers are bitterly estranged for a short period. In the end (after some other twists and turns), they come back together, knowing that they’re too much in love to be apart, knowing that they’re fated to be together. Ironically, they have a car accident in which Cora is killed. The D.A. prosecutes Frank for Cora’s murder, and Frank is convicted and sentenced to death. We learn at the end that he has been telling the story to a priest in his prison cell, awaiting execution.

Postman displays all the distinctive conventions of film noir: the noir look and feel, as well as a typical noir narrative, with the femme fatale, the alienated and doomed antihero, and their scheme to do away with her husband. It has the feeling of disorientation, pessimism, and the rejection of traditional ideas about morality, what’s right and what’s wrong. Further, a great many noir films were either adapted from hard-boiled novels or heavily influenced by them. Last, it’s told in flash-back form through Frank’s voice-over, another noir convention. Indeed, Postman is considered to be a quintessential film noir.

Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice.

But what does that mean? What exactly is film noir? Is it a genre (like a western or a romantic comedy)? Is it a film style constituted by the deep shadows and odd scene compositions? Is it perhaps a cycle of films lasting through a certain period (typically identified as 1941 to 1958)? Is noir a certain mood and tone, that of alienation and pessimism? Each of these answers, amongst others, has been given by one theorist or another as an explanation of just what film noir is. And, given that there is widespread disagreement about what film noir is, there is likewise disagreement about which films count as film noir. Clearly, Postman is a film noir, but is Citizen Kane (1941), for example? Or, perhaps more pointedly, are Beat the Devil (1953) or The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) noir films? Like The Maltese Falcon (1941), both films star noir legend Humphrey Bogart, and both were directed by John Huston, but, whereas The Maltese Falcon is considered to be a noir film, indeed a classic noir, the other two movies are often not so regarded.

In this essay, I’ll give a brief history of the various attempts at defining film noir. I’ll then discuss Nietzsche and the problem of definition, and I’ll conclude by making a modest proposal for a new way of looking at film noir and the problem of its definition.

Socratic Definition

Before examining the various, proposed definitions of film noir, I want to look at one approach to the question of definition generally, namely Socrates’. As a philosopher, Socrates’ central concern was ethics: he wanted to know how to live his life, and he believed that the key to living well was knowledge, specifically knowledge of the virtues. If he’s going to be pious or just, Socrates believes, he has to know what piety and justice are. So, in Plato’s dialogues, in order to achieve the knowledge he wants, Socrates searches for the form of these virtues.

Plato’s theory of forms is a theory of universals and essences. A universal is the category into which things fall. So, for example, individual, physical chairs or desks are what philosophers call “particulars,” whereas the category, “chair,” or “desk,” is the universal or the species, under which those physical items are organized. Particulars are concrete, individual things; whereas universals are abstract categories. So, if the form is film noir, then the particulars would be the individual films which fall into that category: Out of the Past (1947), The Maltese Falcon, and so on.

But, more than this, the notion of the forms is the cornerstone of Plato’s metaphysics, his theory about the nature of reality. For Plato, the continuously changing everyday world of physical objects and events, the particulars, which we see and hear around us is not ultimate reality; it is a pale imitation, like a shadow on a cave wall (to use Plato’s famous analogy). Ultimate reality is not what we perceive with our five senses. Rather, it’s what we grasp with our minds, the universals. The forms are intelligible rather than sensible, they lie outside space, time, and causality, and they’re eternal and unchanging. Further, the forms are the essences of the particulars: they’re what make the individual, physical objects and events what they are. If someone wants to know what this individual thing made up of plastic, metal, and fabric is, you mention the form: chair (or “chairness,” the essence of any physical object of that type). The individual object comes into existence, changes and decays, and ultimately is destroyed. The form, on the other hand, remains the same throughout. So, even if every chair in the world were destroyed, what it means to be a chair—that essence and form—would still be the same, Socrates believes.

So when Socrates asks for a definition, he is not asking for a dictionary definition, which tells us the way we use a word. Rather, he wants a description of the form. He wants to know what real, essential properties these virtues (in his case) have. And if we can do that, articulate the form, then we’ll know exactly what we’re talking about, and we’ll be able to identify anything of that type.

So is there a way of identifying the “form” of film noir? Can we pick out its essential properties and articulate that in a definition?

Defining Film Noir 1: It’s a Genre

There is now a relatively long history of discussion about film noir and, as I mentioned above, a continuing debate about what noir really is. One of the central issues in defining film noir is whether or not it constitutes a genre. So, what’s a genre? Foster Hirsch says: “A genre…is determined by conventions of narrative structure, characterization, theme, and visual design…” And, as one of those who argues that film noir is indeed a genre, he says that film noir has these elements “in abundance”:

Noir deals with criminal activity, from a variety of perspectives, in a general mood of dislocation and bleakness which earned the style its name. Unified by a dominant tone and sensibility, the noir canon constitutes a distinct style of film-making; but it also conforms to genre requirements since it operates within a set of narrative and visual conventions…Noir tells its stories in a particular way, and in a particular visual style. The repeated use of narrative and visual structures…certainly qualifies noir as a genre, one that is in fact as heavily coded as the western.

So, film noir is a genre, Hirsch says, because of the consistent tone, and story-telling and visual conventions amongst the movies. We see all of these, for example, in The Postman Always Rings Twice, as I mentioned above: the tone of dark cynicism and alienation; the narrative conventions like the femme fatale and the flash-back voice-overs; and the shadowy black and white look of the movie. These are the conventions running through the classic noir period, Hirsch says, which define film noir as a genre.

James Damico likewise believes that noir is a film genre, and precisely because of a certain narrative pattern. He describes this pattern as the typical noir plot in which the main character is lured into violence, and usually to his own destruction, by the femme fatale. Again, this is exactly the pattern of Postman: Frank is coaxed into killing Cora’s husband and is ultimately destroyed by his choices and actions. Damico, unlike Hirsch, however, denies that there is a consistent visual style to the films: “I can see no conclusive evidence that anything as cohesive and determined as a visual style exists in [film noir].”

Defining Film Noir 2: It’s Not a Genre

Those who deny that film noir is a genre define it in a number of different ways. In the earliest work on film noir (1955), for example, Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton define noir as a series or cycle of films, whose aim is to create alienation in the viewer: “All the films of this cycle create a similar emotional effect: that state of tension instilled in the spectator when the psychological reference points are removed. The aim of film noir was to create a specific alienation.”

Andrew Spicer also identifies noir as a cycle of films, which “share a similar iconography, visual style, narrative strategies, subject matter and characterisation.” This sounds a good deal like Hirsch’s characterization of noir, but Spicer denies that noir can be defined as a genre (or in most other ways, for that matter), since the expression, “film noir” is “a discursive critical construction that has evolved over time.” In other words, far from being a fixed and unchanging universal category, like one of Plato’s forms, “film noir” is a concept which evolved as critics and theorists wrote and talked about these movies, and is an expression which they applied largely retroactively, to movies in a period of cinema that had already passed.

The Maltese Falcon

Further, in arguing against Damico’s version of noir’s essential narrative, Spicer points out that “there are many other, quite dissimilar, noir plots” than the one Damico describes. Classic examples might include High Sierra (1941) and Pickup on South Street (1953), neither of which includes a femme fatale who coaxes the protagonist to do violence against a third man. In Pickup, for example, pickpocket Skip McCoy (Richard Widmark) steals classified microfilm from a woman, Candy (Jean Peters), on the subway. She’s carrying it for her boyfriend, who is—unbeknownst to her—passing government secrets along to the Communists. The story, then, concerns the efforts of the police to get McCoy to turn the film over to them—which would mean admitting that he’s still picking pockets, thereby putting him in the danger of becoming a three-time loser; and it concerns the efforts of the conspirators to retrieve the film from McCoy by any means necessary, including killing his friend and information dealer, Moe (Thelma Ritter). This is a classic example of a film noir, but doesn’t follow Damico’s narrative pattern.

Spicer goes on to say:

“Any attempt at defining film noir solely through its ‘essential’ formal components proves to be reductive and unsatisfactory because film noir, as the French critics asserted from the beginning, also involves a sensibility, a particular way of looking at the world.”

So, noir is not simply a certain plot line or a visual style achieved by camera angles and unusual lighting, Spicer says. It also involves a “way of looking at the world,” an outlook on life and human existence.

In addition to a series or cycle of movies, film noir is often identified by, or defined as, the particular visual style, mood, tone, or set of motifs characteristic to the form. Raymond Durgnat, for example, says that: “The film noir is not a genre, as the western and gangster film, and takes us into the realm of classification by motif and tone.” The tone is one of bleak cynicism, says Durgnat, and the dominant motifs include: crime as social criticism; gangsters; private eyes and adventurers; middle class murder; portraits and doubles; sexual pathology; psychopaths, etc.

Paul Schrader likewise denies that noir is a genre. He says: “[Film noir] is not defined, as are the western and gangster genres, by conventions of setting and conflict, but rather by the more subtle qualities of tone and mood.” He thus rejects Durgnat’s classification by motif, and focuses his definition on the important element of mood, specifically that of “cynicism, pessimism and darkness.” He goes on to say that “film noir’s techniques emphasize loss, nostalgia, lack of clear priorities, insecurity; then submerge these self-doubts in mannerism and style. In such a world style becomes paramount; it is all that separates one from meaninglessness.”

In a classic essay, Robert Porfirio says that “Schrader was right in insisting upon both visual style and mood as criteria.” The mood at the heart of noir, says Porfirio, is pessimism, “which makes the black film black for us.” The “black vision” of film noir is one of “despair, loneliness and dread,” he claims, and “is nothing less than an existential attitude towards life…” This existentialist outlook on life which infuses noir didn’t come from the European existentialists (like Sartre and Camus), who were roughly contemporaneous with the classic American noir period, says Porfirio. Rather, “It is more likely that this existential bias was drawn from a source much nearer at hand—the hard-boiled school of fiction without which quite possibly there would have been no film noir.” The mood of pessimism, loneliness, dread and despair are to be found in the works of, e.g., Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, and David Goodis, whose writings were a resource for and had a direct influence upon those who created noir films in the classic period, as I mentioned above. I’ll have more to say about Porfirio and the existentialist outlook of noir films below.

Last, R. Barton Palmer likewise rejects the definition of noir as a genre, calling it instead a “transgeneric phenomenon,” since it existed “through a number of related genres whose most important common threads were a concern with criminality…and with social breakdown.” The genres associated with noir include: “The crime melodrama, the detective film, the thriller, and the woman’s picture.” In other words, whatever the noir element in a film noir is, it can be expressed through a number of genres, melodrama, thriller, etc., and so film noir is not itself a genre. It’s “transgeneric.”

Defining Film Noir 3: It Can’t be Defined

Another writer, J. P. Telotte, focuses his discussion of film noir’s definition on the issue of genre, and he, perhaps prudently, somewhat sidesteps the issue of whether or not any of these characterizations of film noir do in fact establish it as a genre. The element of noir films that Telotte claims unites them—without necessarily providing a basis for a calling it a genre—is their rejection of traditional narrative (story-telling) patterns. More than any other type of popular film, Telotte says, “film noir pushes at the boundaries of classical narrative…” This classical narrative would be a straightforward story told from a third-person omniscient point of view, which assumes the objective truth about a situation, involves characters who are goal-oriented and whose motivations make sense, and which has a neat closure at the end (boy gets girl, etc.). Telotte goes on to say that “[noir] films are fundamentally about the problems of seeing and speaking truth, about perceiving and conveying a sense of our culture’s and our own reality…” So what’s common to noir films, Telotte says, is unconventional or non-classical narrative patterns, and these patterns point to problems of truth and objectivity and of our ability to know and understand reality. Some of the techniques which underpin or establish these non-traditional patterns are: 1) Non-chronological ordering of events, often achieved through flashback. As we saw, this is the technique used in Postman, but the best example of this is perhaps The Killers (1946), which brilliantly weaves together Jim Reardon’s (Edmond O’Brien) investigation of Ole Andersen’s (Burt Lancaster) death with flashbacks which tell the story leading up to the murder. 2) Complicated, sometimes incoherent, plot lines, as in The Big Sleep (1946), for example; and 3) Characters whose actions aren’t motivated or understandable in any rational way. For example, why does Frank agree to go ahead with the second (and successful) attempt on Nick’s life in Postman, when it’s such a poor plan and sure to get them caught?

Whereas Telotte sidesteps the issue of definition, James Naremore puts his foot down and concludes that film noir can’t be defined. “I contend that film noir has no essential characteristics,” he says. “The fact is, every movie is transgeneric…Thus, no matter what modifier we attach to a category, we can never establish clear boundaries and uniform traits. Nor can we have a ‘right’ definition—only a series of more or less interesting uses.” Part of the reason film noir can’t be defined, Naremore says, is that—as mentioned above—the term is a kind of “discursive construction,” employed by critics (each of whom has his own agenda), and is used retroactively. The other reason has to do with the nature of concepts and definitions generally. Most contemporary philosophers believe that we don’t form concepts by grouping similar things together according to their essential properties—the technique employed by Socrates and seemingly by most film theorists in talking about noir. Rather, says Naremore, we “create networks of relationship, using metaphor, metonymy, and forms of imaginative association that develop over time.” In other words, our concepts are not discrete categories, but are rather networks of ideas in complex relationships and associations, which we form with experience. Consequently, “categories form complex radial structures with vague boundaries and a core of influential members at the center.” This certainly seems to describe film noir: we all agree that there is a core set of films in the noir canon, such as Double Indemnity (1944) and The Maltese Falcon; but there is a fuzzy boundary, such that we disagree about a great many films and whether or not they fall into the canon, e.g., Casablanca (1942), Citizen Kane, or King Kong (1933).

Robert Mitchum and Jane Greer in Out of the Past

So Naremore argues that film noir can’t be defined, that it has no essential characteristics. On the other hand, there are those, like Nietzsche, who would argue that this doesn’t just apply to these movies, but rather that there’s something problematic about truth and definition generally, even beyond the issues Naremore points out about Socratic definition. Before I can go on to say something about what noir is, I want to examine briefly Nietzsche’s position on these issues.

Nietzsche and the Problem of Truth and Definition

Nietzsche holds a version of what we might call a “flux metaphysics,” the idea that the world, everything, is continually changing, and nothing is stable and enduring. Consequently, he argues, any concept of “being”—something which remains the same throughout change, like Plato’s forms, God, or even the self or ego—is a fiction. Interestingly, he argues that language is one of the primary sources of this fiction. That is, it’s impossible to grasp and articulate a world that’s continually in motion, in which nothing ever stays the same. Thus, “understanding” the world and articulating that understanding becomes a matter of “seeing” parts of the flux as somehow enduring and stable, i.e., it means falsifying what our senses tell us.

One of these falsifications is the subject/predicate distinction that’s built into language. For example, we say “lightning flashes,” as if there were some thing or subject “lightning,” which somehow performs the action of flashing. Similarly, we say “I walk,” “I talk,” “I read,” as if there were some stable ego, self, or subject which was somehow separate from those actions. Nietzsche says: “But there is no such substratum; there is no ‘being’ behind doing, effecting, becoming; ‘the doer’ is merely a fiction added to the deed—the deed is everything.” In other words, in a world in flux, you are what you do. Further, the “doer” or subject created by language, Nietzsche argues, is the source of the concept of being—a stable, unchanging, permanent reality, behind the ever-flowing flux of the world:

“We enter a realm of crude fetishism when we summon before consciousness the basic presuppositions of the metaphysics of language, in plain talk, the presuppositions of reason. Everywhere it sees a doer and doing; it believes in will as the cause; it believes the ego, in the ego as being, in the ego as substance, and it projects this faith in the ego-substance upon all things—only thereby does it first create the concept of ‘thing.’ Everywhere ‘being’ is projected by thought, pushed underneath, as the cause; the concept of being follows and is a derivative of, the concept of ego.”

The fiction begins as merely a stable self, the idea that the ego is something enduring and unchanging and separate from its actions (as opposed to being constituted by those actions), but soon is translated into being; that is, for example, into Plato’s forms and a divinity. Nietzsche says: “I am afraid we are not rid of God because we still have faith in grammar.”

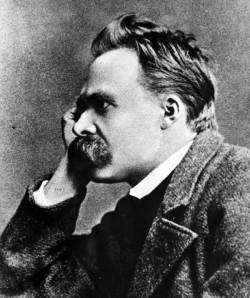

Nietzsche

This falsification introduced by reason and language certainly makes truth, objectivity, and indeed definition problematic, to say the least. In an early and influential essay, Nietzsche says: “Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions…” Elsewhere, he says: “[A]ll concepts in which an entire process is semiotically concentrated elude definition; only that which has no history is definable.” Nietzsche here seems to be agreeing with Socrates: a definition must capture the essence of the thing, that which doesn’t change and thus has no history. The catch here is that, as we’ve seen, Nietzsche denies that there is any such thing, and so he’s denying that anything at all can really be defined. This is a radical position and seems not to bode well for the project of defining film noir. However, and perhaps ironically, I think it’s Nietzsche who will help us better understand what noir is.

What is Noir?

To discover what makes a film a film noir, i.e., what the noir element in the film is, it might be instructive to look briefly at noir literature, and especially so if it’s through the hard-boiled literature that noir films get their existential, pessimistic outlook, as Porfirio says. I’ll take as an example of this literature a work by David Goodis, who was the author of Dark Passage, which was later made into a film starring Bogart and Bacall. The first paragraph of Goodis’ Night Squad reads:

“At 11:20 a fairly well-dressed boozehound came staggering out of a bootleg-whiskey joint on Fourth Street. It was a Friday night in mid-July and the humid heat was like a wave of steaming black syrup confronting the boozehound. He walked into it and bounced off and braced himself to make another try. A moment later something hit him on the head and he sagged slowly and arrived on the pavement flat on his face.”

We instantly recognize here the clipped, gritty phrasing of the hard-boiled school; the dirty gutter setting; and the down-on-his-luck character. The boozehound is being mugged by three men, while a fourth man, Corey Bradford—who turns out to be the protagonist—watches from the other side of the street. Bradford is a former dirty cop and forces the muggers to give him the boozehound’s money. He keeps most of it for himself, but returns a dollar to the boozehound for cab fare home. Instead of going home, however, the boozehound takes the dollar—his only money—and goes back into the bootleg-whiskey joint for another drink. Before he does, he mutters, “The trouble is, we just can’t get together, that’s all.” Bradford interprets this to mean, “we just can’t get together on what’s right and what’s wrong.”

The story largely takes place in a Philadelphia neighborhood called “The Swamp,” where Bradford grew up. The area is just as run-down, dirty, and crime-infested as its name implies. In an interior monologue about the neighborhood, Bradford reflects on how tough the place is, and he has nothing but good things to say about the prostitutes. They’re “performing a necessary function,” like the sewer workers and the trash collectors. He says:

“If it wasn’t for the professionals, there’d be more suicides, more homicides. And more of them certain cases you read about, like some four-year-old girl getting dragged into an alley, some sixty-year-old landlady getting hacked to pieces with an axe.”

If the denizens of the swamp couldn’t vent their violent and sexual impulses with the prostitutes, they’d take them out on little girls and old ladies. So it’s a good thing we have the pros.

Last, I’ll mention in passing that the femme fatale of this story, Lita, is married to the gangster who runs The Swamp. When Bradford first meets her, Goodis describes her thus: “She was of medium height, very slender. Her hair was platinum blonde. Contrasting with her deep, dark green eyes.” And she’s holding a book: “Corey could see the title on the cover. He didn’t know much about philosophy but he sensed that the book was strictly for deep thinkers. It was Nietzsche, it was Thus Spake Zarathustra.”

What we see here, and what makes this story noir, is the tone and mood, and the sensibility, the outlook on life, that the critics and writers mentioned above discuss. We see bleak cynicism (Durgnat), for example, in the protagonist saving the boozehound from getting mugged, only to keep the latter’s money for himself. We witness the loss and lack of clear priorities (Schrader) in the same scene, and in the Bradford’s appraisal of the prostitutes. Alienation is clearly present (Borde and Chaumeton); the whole story is one of a man adrift, a man who has lost balance and the meaning and value of his life. And we see existential pessimism (Porfirio). This is clearly evident in the image of the boozhound going back into the bar to spend his last dollar on another drink; and in the dark picture of human nature that Goodis paints when he discusses the need for prostitutes to vent our violent urges.

One other thing, which is related to all these other elements, and which some writers discuss, but which I want to emphasize, is what we might call the inversion of traditional values, and the loss of the meaning of things. That is, at the heart of the noir mood or tone of alienation, pessimism, and cynicism is, on the one hand, the rejection or loss of clearly defined ethical values (we can’t “get together on what’s right and what’s wrong”); and, on the other hand, the rejection or loss of the meaning or sense of human existence. In essence, I think Porfirio is on the right track in talking about the noir sensibility as a kind of “existential outlook” on life.

Further, I’m agreeing with those who say that what makes a film a film noir is a particular mood, tone, and sensibility, an outlook on life. This is clear because it’s that tone and sensibility which, as I said, links the literature and the films. Thus, I think that the narrative elements (story-telling conventions), and the filmmaking techniques (oblique camera angles, deep focus, low-key lighting, etc.), are secondary to the mood and sensibility. They are used to communicate that mood and sensibility, but it’s the latter which makes the film a noir.

The Death of God and the Meaning of Noir

As I mentioned, Nietzsche can help throw light on what film noir is, despite his skepticism about truth, essences, and definition. One of Nietzsche’s most infamous and provocative statements is that “God is dead.” What he means by this is that not only Western religions, but metaphysical systems such as Plato’s, have become untenable. Both Platonism and Christianity, for example, claim that there is some permanent and unchanging other-worldly realm or substance, Plato’s forms or God and heaven, respectively. This unchanging other-worldly something is set in opposition to the here and now, the changing world around us (forms vs. particulars; heaven vs. earth, etc.); and it’s the source of, or foundation for, our understanding of human existence, our morality, our hope for the future, amongst other things.

Again, Nietzsche says that the fiction of being is generated originally through the falsifications involved in reason and language. This concept of being is exposed as a fiction beginning in the modern period, Nietzsche argues, when natural empirical science begins to replace traditional metaphysical explanations of the world. We cease to believe in the myth of creation, for example, and modern philosophers tend to reject Plato’s idea of other-worldly forms. Thus, throughout the modern and into the contemporary period, religion and philosophy—as metaphysical explanations of the world—are supplanted by natural science. At the same time, we try to hold onto our old understanding of human existence, our ethics, an ever-more-feeble belief in an afterlife, etc. What finally, and gradually, dawns on us, says Nietzsche, is that there’s no longer any foundation or justification for these adjuncts of metaphysics, once the latter is lost. We realize more and more the hollowness and untenability of our old outlook, our old values.

The result of this is devastating. We no longer have any sense of who and what we are as human beings; there’s seemingly no foundation any longer for the meaning and value of things, including ethical values, good and evil; there’s no longer any hope for an afterlife—this life has to be taken and endured on its own terms. Before the death of God, as good Platonists or Christians (or Jews or Moslems), we knew who and what we were, the value and meaning our lives had, what we had to do to live a righteous life; and now we’re set adrift. We’re alienated, disoriented, off-balance; the world is senseless and chaotic; and there’s no transcendent meaning or value to human existence.

This death of God, then—the loss of permanence, a transcendent source of value and meaning, and the resulting disorientation and nihilism—leads to existentialism and its worldview. Porfirio characterizes existentialism as:

“an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that he cannot accept. It places its emphasis on man’s contingency in a world where there are no transcendental values or moral absolutes, a world devoid of any meaning but the one man himself creates.”

As a literary/philosophical phenomenon, set in its particular place in history, existentialism is continental Europe’s reaction to the death of God.

My proposal, then, is that noir can also be seen as a sensibility or worldview which results from the death of God, and thus that film noir is a type of American artistic response to, or recognition of, this seismic shift in our understanding of the world. This is why Porfirio is right in pointing out the similarities between the noir sensibility and the existentialist view of life and human existence. Though they are not exactly the same thing, they are both reactions, however explicit and conscious, to the same realization of the loss of value and meaning in our lives.

A (Slightly) Different Approach

Seeing noir as a response or reaction to the death of God helps explain the commonality of the elements that thinkers have noted in noir films. For example, it explains the inherent pessimism, alienation and disorientation in noir. It affirms that noir is a sensibility or an outlook, as some say. It explains the moral ambiguity in film noir, as well as the threat of nihilism and meaninglessness that some note.

As I said, the death of God doesn’t just (or even necessarily) mean the rejection of religion. For Americans, our belief in what Nietzsche is calling “God,” the sense, order and meaning of our lives and the world, is encapsulated in American idealism: the faith in God, progress, and the indomitable American spirit. Consequently, as Palmer notes, “Film noir…offers the obverse of the American dream.” Most argue that the sources of this obversion or reversal are (or include): anxiety over the war and the postwar period; the Communist scare; the atomic age; the influx of German immigrants to Hollywood; and the hard-boiled school of pulp fiction. Indeed, it’s via these influences that an awareness or a feeling came upon us, seeped into the American consciousness, that our old ways of understanding ourselves and the world, and the values that went along with these, were gone or untenable. We lost our orientation in the world, the meaning and sense that our lives had, and clear-cut moral values and boundaries.

The similarities between European existentialism and film noir are apparent, as Porfirio points out in his essay. In the classic existentialist work, The Stranger, for example, Camus depicts the alienation and disorientation of a post-Nietzschean world, one without transcendent meaning or value. In the book, the main character reacts little to his mother’s death; shoots and kills a man for no good reason; and seems indifferent to his own trial and impending execution.

Similarly, when Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) shrugs off his partner’s murder, or turns his lover, Bridgid (Mary Astor), over to the police in The Maltese Falcon; or in The Killers when Ole Andersen passively awaits his assassins, even after being warned that they’re coming, we get a sense of the same alienation, and lack of sense and meaning. And, since film noir is a visual medium, these noirish elements are also conveyed through the lighting and camera techniques. So, for example, extreme close-ups of Hank Quinlan’s (Orson Welles) bloated face in Touch of Evil (1958), or the tilted camera shot of Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) in a hospital bed in Kiss Me Deadly (1955), further serve to express alienation and disorientation.

Finally, considering noir to be a response to the death of God also verifies J. P. Telotte’s claim that noir films are “fundamentally about the problems of seeing and speaking truth,” since it’s in a post-Nietzschean world, in the wake of the death of God, that seeing and speaking the truth become problematic. Consequently, and ironically, what makes truth problematic, and what makes definition impossible, according to Nietzsche—the abandonment of essences, the resulting flux metaphysics, rejection of anything permanent and unchanging in the universe, i.e., the death of God—is the same thing that makes noir what it is. That is, the death of God is both the meaning of noir, and—if we’re to believe Nietzsche—also what makes noir impossible to define.

The relationship between Plato and Socrates is somewhat complex. Socrates never wrote anything. He much preferred to engage people in conversation. Plato was one of Socrates’ friends and pupils. Most of Plato’s writings are in the form of dialogues, they’re narratives, and Socrates is very often the main character. Consequently, when we talk about Socrates saying something, we’re most of the time referring to one of Plato’s dialogues.

See Plato’s cave allegory in Republic, Book VII (514a – 517d).

For a discussion of Plato’s theory of forms see his Phaedo, 65d, or Republic, 475e – 476a.

There are many other ways of thinking about definition, both ancient and contemporary. I mention Socrates because his is a classic approach to the issue, and because he makes a nice foil for Nietzsche.

I’m not pretending that the history I’m giving is complete or that it mentions every important work or statement on the topic. I merely want to provide the reader with a flavor of the discussion and point out some of the definitions provided in some of the canonical works on noir.

Wes D. Gehring, in the Introduction to Handbook of American Film Genres, says a genre in film studies “represents the division of movies into groups which have similar subjects and/or themes.” Wes D. Gehring, “Introduction,” Handbook of American Film Genres,” ed. by Wes D. Gehring, Greenwood Press, 1988, p. 1.

Foster Hirsch, The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir, Da Capo Press, 1981, p. 72.

See James Damico, “Film Noir: A Modest Proposal,” in Film Noir Reader, ed. by Alain Sliver and James Ursini, Limelight Editions, 1996, p. 103.

Ibid., p. 105. This is in contrast to those like Janey Place and Lowell Peterson, who explicitly identify noir as a visual style (see their essay, “Some Visual Motifs of Film Noir,” in the same volume). In Somewhere in the Night (Henry Holt and Company, 1997), Nicholas Christopher also argues (though less explicitly than Damico) that film noir is a genre because of a certain narrative pattern. See p. 7 – 8.

Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton, “Towards a Definition of Film Noir,” trans. by Alain Silver, in Film Noir Reader, p. 25.

Andrew Spicer, Film Noir, Pearson Education Limited, 2002, p. 4.

Ibid., p. 24.

The term “film noir” was coined by French film critics, unbeknownst to American filmmakers during the period of classic film noir (i.e., while they were making these movies), and wasn’t part of the American film vocabulary until after that classic period had ended.

To be fair, Damico calls his plot description simply the “truest” or “purest” example of film noir, and admits that there are other noir plots. However, the sheer number and variety of the other plots would seem to undermine his argument.

Ibid., p. 25.

Raymond Durgnat, “Paint it Black: the Family Tree of the Film Noir,” in Film Noir Reader, p. 38.

Paul Schrader, “Notes on Film Noir,” in Film Noir Reader, p. 53.

Ibid., p. 58.

Robert Porfirio, “No Way Out: Existential Motifs in the Film Noir,” in Film Noir Reader, p. 78.

Ibid., p. 80

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 82 – 83.

R. Barton Palmer, Hollywood’s Dark Cinema: The American Film Noir, Twayne Publishers, 1994, p. 30.

Ibid., p. x.

“This overview of film noir’s main narrative techniques should come with a warning: like the films themselves, this taxonomy provides but a partial, although valuable, view of their workings, while it points toward, if it never quite satisfactorily resolves, the question of noir’s generic status.” J. P. Telotte, Voices in the Dark: The Narrative Patterns of Film Noir, University of Illinois Press, 1989, p. 31.

Ibid., p. 12.

Ibid., p. 31.

James Naremore, More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts, University of California Press, 1998, p. 5.

Ibid., p. 6.

Ibid., p. 5.

Ibid., p. 6. Amongst others, Naremore has Ludwig Wittgenstein in mind here. In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein argues that there isn’t a set of essential properties or necessary and sufficient conditions that link games together (how are football and tic tac toe related?); rather there is only a loose network in which each game is connected to at least one other by a “family resemblance.” This would seem to be the case, too, with noir.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. by Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale, Vintage Press, 1989, p. 45.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, “Reason in Philosophy,” from The Portable Nietzsche, ed. by Walter Kaufmann, Penguin, 1976, p. 483.

Ibid.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense,” in Philosophy and Truth: Selections from Nietzsche’s Notebooks of the Early 1870’s, trans. Daniel Breazeale (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Paperback Library, 1979), 84.

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, p. 80.

I choose Goodis because not only is he one of my favorite hard-boiled authors, but also because he’s much less well-known than Chandler or Thompson, e.g., and undeservedly so, I think.

David Goodis, Night Squad, First Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1992, p. 3. Admittedly, Night Squad is a later work of Goodis (1961), and so comes after the classic film noir period. However, it is still representative of Goodis’ work and of hard-boiled pulp literature generally.

Ibid., p. 8.

Ibid., p. 11.

Ibid., p. 44 – 45.

In film noir “Good and evil go hand in hand to the point of being indistinguishable,” say Borde and Chaumeton, “Towards a Definition of Film Noir,” p. 25.

As Porfirio says: “This sense of meaninglessness is…not the result of any sort of discursive reasoning. Rather it is an attitude which is worked out through the mise en scène and plotting.” “No Way Out,” p. 89.

This is first expressed in a passage called “The Madman,” in Nietzsche’s The Gay Science. (See Walter Kaufmann’s translation: Vintage Books, 1974, p. 181.)

“No Way Out,” p. 81.

Hollywood’s Dark Cinema, p. 6.

Voices in the Dark, p. 31.

September 21, 2014

WHY I WRITE

“Write with blood, and you will experience that blood is spirit.” –Nietzsche.

This is my entry for a blog hop (sounds like a drunk frog) called “Why I Write.” It was Drew Chial who tagged me in his excellent entry, so you can blame him.

Origins

I do two kinds of writing: academic (philosophical essays, though this extends into my work in popular culture and philosophy, so it’s also popular) and fiction-writing, specifically suspense novels.

As so many of us, I started writing some very bad poetry and some prose pieces when I was a teen. Once I fell in love with philosophy and started into grad school, I began my career in academic writing. I have a great attention to detail, and I’m very analytical and can focus intently. Further, I make copious notes, and I outline thoroughly, and I never start an essay until I’m sure of exactly what I’m going to say and argue; so my academic writing is quite rigorous, and my skills at the craft of prose writing have developed over the years.

During my grad days I started doing a kind of journaling and writing stream-of conscious prose pieces, but I did so when I was drunk and depressed, so that stuff’s kind of interesting to read, but it didn’t amount to much.

I started writing crime/suspense by accident. I started working on a screenplay in grad school with a friend of mine over many, many beers. When we began, we didn’t have any particular genre in mind; we just wanted to come up with a story, and it turned out to be a suspense/mystery. We came up with the outline of the plot and some character sketches, and he left it to me to put it into screenplay format, which I didn’t know how to do. I left it sit in my desk drawer for a couple of years, then decided one summer to turn it into a novel. I wrote, rewrote, edited, read in the genre (I’d never read any suspense or crime literature until I started writing it), and finally came up with a complete draft. I enjoyed the process so much, that I started right away on a second one, and I never stopped.

In suspense, the influences I always name are: Elmore Leonard, Raymond Chandler, David Goodis, James Ellroy, and Jim Thompson. So at first I wrote a Jim Thompson novel, and then an Elmore Leonard novel, and then a James Ellroy novel. I started looking for a literary agent—though as I would later discover, it was too early to do so. When that went nowhere, I started sending out queries to small, independent presses, and it was thus that I found a publisher for my fourth novel written, Dark as Night.

Dark as Night

I recall that it was when I was working on novel #6 or #7 (and after as many years or more) that I found my voice. That’s what I mean when I say I went looking for an agent too soon. I’ve become a big believer in the rule of thumb that you should put in about ten years or so of writing before you even think about trying to get published (if ever). Most of us don’t know how bad we are at it at first, so I understand the temptation to want to get your stuff out there; but, trust me, you don’t want to rush it. I always compare the craft of writing to singing: those who sing off key don’t know they’re doing it. You have to learn to hear your writing, to hear your mistakes, and that takes a great deal of time and experience.

I eventually did find a respectable agent, and he shopped my manuscripts around for a few years, until in 2013 Adam Chromy offered me the opportunity of publishing two of my books as e-novels via The Rogue Reader. One was a reprint of Dark as Night, and the other was a complete rewrite of the first novel I wrote, now entitled Killer’s Coda. I only discovered then that my agent has died (which well explains why I hadn’t heard from him in a while).

Killer’s Coda

Why I write

None of the above exactly explains the topic at hand, why I write, but it provides the background for giving an answer.

I write philosophy essays because philosophy is the love and passion of my intellectual life. What I didn’t mention above was that it was as a depressed teen that I discovered philosophy (after having dropped out of one college and changed majors), and it spoke to me in a very deep and personal way. I’d always been looking for some kind of depth, some kind of intellectual guidance. I somehow intuitively knew there were big questions, big ideas out there that someone, somewhere was talking about, and I finally found the conversation and joined it immediately. So writing philosophy essays is indeed part of my job; it’s part of what I get paid to do for a living (which is remarkable in itself), but it’s also my way of making a small contribution to that ongoing conversation of great ideas. I can’t imagine doing anything else, can’t imagine a better job (well, okay, if they paid me a whole lot more, that’d be pretty cool).

The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers

With regard to fiction writing, the answer is perhaps less clear. I take a great deal of satisfaction from writing novels—it’s fun and rewarding. But I think in general there’s something deeply human and very important about story-telling, about constructing narratives. We all have a deep desire to make sense of our lives, to think that there’s some point, some overarching meaning to them, and in a way living is constructing the narrative of your own life. We tell stories to help ourselves make sense of the world and our lives. I think we capture a lot by referring to a human being as “the story-telling animal.” It pegs us as language-users, for whom our lives and events in our lives matter, and who have a deep need for communication—that is, a deep need for community, being with others. Further, it implies in at least an oblique way what I mentioned above: The question of our existence, and the meaning of our existence, is of profound importance to us: we need to make sense of it all.

Consequently, I write stories about guys trying to shoot each other…

Coda

For a very long time the two sorts of writing I did were completely separate; I had philosophy on the one hand, and fiction on the other. At one point or another, I attempted to integrate some philosophical content or ideas into my stories, but the attempt always failed. The ideas always felt tacked on (which they were, really). It’s only very recently that I’ve learned to bring these two passions of mine together in, for me, a very exciting way. In large part, I accomplished this by expanding upon the genre I was writing in. I had to move beyond straightforward suspense tales in order to do it (by incorporating some of what might be identified as sci fi or dystopic elements). But the whole thing has come together also because of some of my recent revelations about storytelling itself. That all began when I started reading books on screenwriting (I’m particularly indebted to Robert McKee’s invaluable book, Story). But I’ve had some further revelations that I’ll talk about in a future post.

For the purposes of this blog hop, then, I’m passing the baton to:

Cool guy Alex Nader, who’s novel Beasts of Burdin I’m currently reading. Follow Alex on Twitter: @AlexNaderWrites, and check out his blog, “Alexander Nader–Wordsmith.”

And

My Twitter soul mate, Jess West. Follow Jess on Twitter: @West1Jess, and have a look at her excellent blog, “Write this Way.”

[contact-form]

September 19, 2014

Symbolism, Meaning, and Nihilism in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction

I was just interviewed by Brian Turnof for his radio show The Mind’s Eye on www.ztalkradio.com. It’s the 20th anniversary of the release of Pulp Fiction (if you can believe it), and, given my work on Tarantino, Brian wanted to hear my thoughts on the film and its legacy. It was a fun interview, and I appreciate the opportunity to have done it. In light of the anniversary and the interview, I thought I’d post my original essay on Pulp Fiction. It appeared first in Philosophy Now, but you can also find it in my The Philosophy of Film Noir. Enjoy!

The Philosophy of Film Noir

“Symbolism, Meaning, and Nihilism in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction“

Nihilism is a term which describes the loss of value and meaning in people’s lives. When Nietzsche proclaimed that “God is dead,” he meant that Judeo-Christianity has been lost as a guiding force in our lives, and there is nothing to replace it. Once we ceased really to believe in the myth at the heart of Judeo-Christian religion, which happened after the scientific revolution, Judeo-Christian morality lost its character as a binding code by which to live one’s life. Given the centrality of religion in our lives for thousands of years, once this moral code is lost and not replaced, we are faced with the abyss of nihilism: darkness closes in on us, and nothing is of any real value any more; there is no real meaning in our lives, and to conduct oneself and one’s life in one way is just as good as another, for there is no overarching criterion by which to make such judgments.

Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction is an odd film. It’s a seemingly complete narrative which has been chopped into vignettes and rearranged like a puzzle. It’s a gangster film in which not a single policeman is to be found. It’s a montage of bizarre characters, from a black mobster with a mysterious bandage on the back of his bald head to hillbilly sexual perverts; from henchmen dressed in black suits whose conversations concern what fast food items are called in Europe to a mob problem-solver who attends dinner parties early in the morning dressed in a full tuxedo. So, what is the film about? In general, we can say that the film is about American nihilism.

The Vignettes

First, a quick run-down of the film:

Part I: Ringo and Honeybunny decide to rob a coffee shop. Jules and Vincent discuss what a Quarter Pounder with Cheese is called in France. They collect a briefcase which belongs to Marsellus Wallace from Brett, Marvin, et. al. Before Jules kills Brett, he quotes a passage from the Old Testament. Marsellus has asked Vincent to take out Mia (Mrs. Marsellus Wallace), and Vincent is nervous because he heard that Marsellus maimed Tony Rocky Horror in a fit of jealousy. Vincent buys heroin and gets high, then takes Mia out to Jack Rabbit Slim’s, a restaurant which is full of old American pop icons: Buddy Holly, Marilyn Monroe, Ed Sullivan, Elvis; they win a dance contest. Mia mistakes heroin for cocaine and overdoses, and Vincent has to give her a cardiac needle full of adrenaline to save her.

PART II: Butch agrees to throw a fight for Marsellus Wallace. Butch as a child receives a watch from his father’s friend, an army comrade who saved the watch by hiding it in his rectum while he was in a Vietnamese prisoner of war camp. Butch double crosses Marsellus and doesn’t throw the fight; his boxing opponent is killed. Butch must return to his apartment, despite the fact that Marsellus’ men are looking for him, to get his watch; he kills Vincent. Butch tries to run over and kill Marsellus; they fight and end up in a store with Zed, Maynard and the Gimp, hillbilly sexual perverts. The perverts have subdued and bound Butch and Marsellus, and the perverts begin to rape Marsellus. Butch gets free and saves Marsellus by killing a hillbilly and wounding another with a Samurai sword.

PART III: Returning to the opening sequence, one of the kids Jules and Vincent are collecting from tries to shoot them with a large handgun; he fails, and Jules takes this as divine intervention. Jules and Vincent take Marvin and the briefcase; Marvin is shot accidentally, and the car becomes unusable. Jules and Vincent stop at Jimmy’s, and Marsellus sends Winston Wolf to mop up. Jules and Vincent end up in the coffee shop which Ringo and Honeybunny are robbing. Ringo wants to take the briefcase, but Jules won’t let him. Jules quotes the Biblical passage again to Ringo and tells him that he would quote this to someone before he killed that person. This time, however, Jules is not going to kill Ringo. Ringo and Honeybunny take the money from the coffee shop; Jules and Vincent retain the briefcase.

Pulp Fiction DVD

Transient Symbols

As I said, in general, the film is about American nihilism. More specifically, it is about the transformation of two characters: Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) and Butch (Bruce Willis). In the beginning of the film, Vincent (John Travolta) has returned from a stay in Amsterdam, and the content of the conversation between Jules and Vincent concerns what Big Macs and Quarter Pounders are called in Europe, the Fonz on Happy Days, Arnold the Pig on Green Acres, the pop band Flock of Seagulls, Caine from Kung Fu, tv pilots, etc. These kinds of silly references seem upon first glance like a kind of comic relief, set against the violence that we’re witnessing on the screen. But this is no mere comic relief. The point is that this is the way these characters make sense out of their lives: transient, pop cultural symbols and icons. In another time and/or another place people would be connected by something they saw as larger than themselves, most particularly religion, which would provide the sense and meaning that their lives had and which would determine the value of things. This is missing in late 20th (and now early 21st) Century America, and is thus completely absent from Jules’ and Vincent’s lives. This is why the pop icons abound in the film: these are the reference points by which we understand ourselves and each other, empty and ephemeral as they are. This pop iconography comes to a real head when Vincent and Mia (Uma Thurmon) visit Jack Rabbit Slim’s, where the host is Ed Sullivan, the singer is Ricky Nelson, Buddy Holly is the waiter, and amongst the waitresses are Marilyn Monroe and Jane Mansfield.

The pop cultural symbols are set into stark relief against a certain passage from the Old Testament, Ezekiel 25:17:

“The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he, who in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness, for he is truly his brother’s keeper and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know my name is The Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.”

Jules quotes this just before he kills someone. The point is that the passage refers to a system of values and meaning by which one could lead one’s life and make moral decisions. However, that system is missing from Jules’ life and so the passage becomes meaningless to him. Late in the film he tells us: “I’ve been saying that shit for years, and if you heard it—that meant your ass. I never gave much thought to what it meant, I just thought it was some cold blooded shit to say to a motherfucker before I popped a cap in his ass.”

The Hierarchy of Power

The absence of any kind of foundation for making value judgments, the lack of a larger meaning to their lives, creates a kind of vacuum in their existence which is filled with power. With no other criteria available to them by which to order their lives, they fall into a hierarchy of power, with Marsellus Wallace (Ving Rhames) at the top and themselves as henchmen below. Things come to have value in their lives if Marsellus Wallace declares it to be so. What he wants done, they will do. What he wishes becomes valuable for them and thus becomes the guide for their actions at the moment, until the task is completed by whatever means necessary. This is perfectly epitomized by the mysterious briefcase which Jules and Vincent are charged to return to Marsellus. It is mysterious because we never actually see what’s in it, but we do see people’s reactions to its obviously valuable contents. The question invariably arises: what’s in the briefcase? However, this is a trick question. The answer is really: it doesn’t matter. It makes no difference what’s in the briefcase. All that matters is that Marsellus wants it back, and thus the thing is endowed with worth. If Jules and Vincent did have an objective framework of value and meaning in their lives, they would be able to determine whether what was in the briefcase was ultimately of value, and they would be able to determine what actions were justified in retrieving it. In the absence of any such framework, the briefcase becomes of ultimate value in and of itself, precisely because Marsellus says so, and any and all actions required to procure it become justified (including, obviously, murder).

In addition to the pop iconography in the film, the discourse on language here concerns naming things. What is a Big Mac called? What is a Quarter Pounder called? What is a Whopper called? (Vincent doesn’t know; he didn’t go to Burger King.) When Ringo (Tim Roth) calls the waitress “garçon,” she informs him: “‘garçon’ means ‘boy.’” Also, when Butch’s girlfriend refers to his means of transportation as a “motorcycle,” he insists on correcting her: “It’s not a motorcycle, it’s a chopper.” And yet—and here’s the crux—when a lovely Hispanic cab driver asks Butch what his name means, he replies: “This is America, honey; our names don’t mean shit.” The point is clear: in the absence of any lasting, transcendent objective framework of value and meaning, our language no longer points to anything beyond itself. To call something good or evil renders it so, given that there is no higher authority or criteria by which one might judge actions. Jules quotes the Bible before his executions, but he may as well be quoting the Fonz or Buddy Holly.

Objective Values

I’ve been contrasting nihilism with religion as an objective framework or foundation of values and meaning, because that’s the comparison that Tarantino himself makes in the film. There are other objective systems of ethics, however. We might compare nihilism to Aristotelian ethics, for example. Aristotle says that things have natures or essences and that what is best for a thing is to “achieve” or realize its essence. And in fact whatever helps a thing fulfill its nature in this way is by definition good. Ducks are aquatic birds. Having webbed feet helps the duck to achieve its essence as a swimmer. Therefore, it’s good for the duck to have webbed feet. Human beings likewise have a nature which consists in a set of capacities, our abilities to do things. There are many things that we can do: play the piano, build things, walk and talk, etc. But the essentially human ability is our capacity for reason, since it is reason which separates us from all other living things. The highest good, or best life, for a human being, then, consists in realizing one’s capacities, most particularly the capacity for reason. This notion of the highest good, along with Aristotle’s conception of the virtues, which are states of character which enable a person to achieve his essence, add up to an objective ethical framework according to which one can weigh and assess the value and meaning of things, as well as weigh and assess the means one might use to procure those things. To repeat, this sort of a framework, whether based on religion or reason, is completely absent from Jules’ and Vincent’s lives. In its absence, pop culture is the source of the symbols and reference points by which the two communicate and understand one another; and without reason or a religious moral code to determine the value and meaning that things have in their lives, Marsellus Wallace dictates the value of things. This lack of any kind of higher authority is depicted in the film by the conspicuous absence of any police presence whatever. This is a gangster film, in which people are shot dead, others deal and take drugs, drive recklessly, etc., there are car accidents, and yet there is not a single policeman to be found. Again, this symbolizes Marsellus’ absolute power and control in the absence of any higher, objective authority.

Jules

Pulp Fiction is in part about Jules’ transformation. When one of his targets shoots at him and Vincent from a short distance, empties the revolver, and misses completely, Jules interprets this as divine intervention. The importance of this is not that it really was divine intervention, but rather that the incident spurs Jules on to reflect on what is missing. It compels him to consider the Biblical passage that he’s been quoting for years without giving much thought to it. Jules begins to understand—however confusedly at first—that the passage he quotes refers to an objective framework of value and meaning that is absent from his life. We see the dawning of this kind of understanding when he reports to Vincent that he’s quitting the mob, and then (most significantly) when he repeats the passage to Ringo in the coffee shop and then interprets it. He says:

“I’ve been saying that shit for years, and if you heard it—that meant your ass. I never gave much thought to what it meant, I just thought it was some cold blooded shit to say to a motherfucker before I popped a cap in his ass. But I saw some shit this morning that made me think twice. See, now I’m thinking, maybe it means: you’re the Evil Man, and I’m the Righteous Man, and Mr. 9mm here—he’s the Shepherd protecting my righteous ass in the valley of darkness. Or it could mean: you’re the Righteous Man, and I’m the Shepherd; and it’s the world that’s evil and selfish. Now, I’d like that, but that shit ain’t the truth. The truth is: you’re the Weak and I’m the Tyranny of Evil Men. But I’m trying Ringo, I’m trying real hard to be the Shepherd.”

Jules offers three possible interpretations of the passage. The first interpretation accords with the way he has been living his life. Whatever he does (as commanded by Marsellus) is justified, and thus he is the Righteous Man, with his pistol protecting him, and whatever stands in his way is bad or evil by definition. The second interpretation is interesting and seems to go along with Jules’ pseudo-religious attitude following what he interprets as a divine-mystical experience (he tells Vincent, recall, that he wants to wander the earth like Caine on Kung Fu). In this interpretation, the world is evil and selfish, and apparently has made Jules do all the terrible things he’s done up to that point. He’s now become the Shepherd, and he’s going to protect Ringo (who after all is small potatoes in mob terms, robbing coffee shops, etc.) from this evil. But that’s not the truth, he realizes. The truth is that he himself is the evil that he’s been preaching about (unwittingly) for years. Ringo is weak, neither good enough to be righteous, nor strong enough to be as evil as Jules and Vincent. And Jules is trying to transform himself into the shepherd, to lead Ringo through the valley of darkness. Of course, interestingly, the darkness is of Jules’ own making, such that the struggle to be the shepherd is Jules’ struggle with himself not to revert to evil. In this struggle, he buys Ringo’s life. Ringo has collected the wallets of the customers in the coffee shop, including Jules’, and Jules allows him to take fifteen hundred dollars out of it. Jules is paying Ringo the fifteen hundred dollars to take the money from the coffee shop and simply leave, so that he (Jules) won’t have to kill him. Note that no such transformation has taken place for Vincent, who exclaims: “Jules, you give that fucking nimrod fifteen hundred dollars, and I’ll shoot him on general principle.” The principle is of course whatever means are necessary to achieve my end are justified, the end (again) most often determined by Marsellus Wallace. This attitude of Vincent’s is clearly depicted in his reaction to Mia’s overdose. He desperately tries to save her, not because she is a fellow human being of intrinsic worth, but because she is Marsellus’ wife, and he (Vincent) will be in real trouble if she dies. Mia has value because Marsellus has made it so, not because of any intrinsic or objective features or characteristics she may possess.

Butch

The other transformation in the film is that of Butch. There is a conspicuous progression in the meaning and relevance of the violence in the story. In the beginning, we see killings that are completely gratuitous: Brett and his cohorts, and particularly Marvin, who is shot in the face simply because the car went over a bump and the gun went off. There is also the maiming of Tony Rocky Horror, the reason for which is hidden from all, save Marsellus. Again, this is evidence that it is Marsellus himself who provides the meaning and justification for things, and his reasons—like God’s—are hidden from us. (This may in fact be what the bandage on his head represents: the fact that Marsellus’ motives and reasons are hidden to us. Bandages not only help to heal, they also hide or disguise what we don’t want others to see.) The meaninglessness of the violence is also epitomized in the boxing match. Butch kills his opponent. When the cab driver, Esmarelda Villalobos (Angela Jones), informs him of this, his reaction is one of complete indifference. He shrugs it off. Further, when Butch gets into his jam for having double-crossed Marsellus, he initially decides that the way that he is going to get out of it is to become like his enemy, that is, to become ruthless. Consequently, he shoots and kills Vincent, and then he tries to kill Marsellus by running him over with a car.

The situation becomes interesting when Butch and Marsellus, initially willing to kill one another without a second’s thought, find themselves in the same unpleasant situation: held hostage by a couple of hillbillies who are about to beat and rape them. I noted earlier the conspicuous absence of policemen in the film. The interesting quasi-exception to this is the pervert, Zed. Marsellus is taken captive, bound and gagged. When Zed shows up he is dressed in a security guard’s uniform, giving him the appearance of an authority figure. He is only a security guard, and not a real policeman, however, and this is our clue to the arbitrariness of authority. In the nihilistic context in which these characters exist, in the absence of an objective framework of value to determine right, justice and goodness, Marsellus Wallace is the legislator of values, the ultimate authority. In this situation, however, his authority has been usurped. Zed holds the shotgun now, and he takes his usurpation to the extreme by raping Marsellus.

Butch’s Transformation

Just as Jules’ transformation had a defining moment, namely, when he is fired upon and missed, so too Butch’s transformation has a defining moment. This is when he is about to escape, having overpowered the Gimp, but returns to save Marsellus. As I said, initially the violence is gratuitous and without meaning. However, when Butch returns to the cellar to aid Marsellus, the violence for the first time has a justification: as an act of honor and friendship, he is saving Marsellus, once his enemy, from men who are worse than they are. Note that Butch gets out of his jam not by becoming like his enemy, i.e., ruthless, but in fact by saving his enemy.

Butch’s transformation is represented by his choice of weapons in the store: a hammer, a baseball bat, a chainsaw, and a Samurai sword. He overlooks the first three items and chooses the fourth. Why? The sword clearly stands out in the list. First, it’s meant to be a weapon, while the others are not, and I’ll discuss that in a moment. But it also stands out because the first three items (two of them particularly) are symbols of Americana. They represent the nihilism that Butch is leaving behind, whereas the Samurai sword represents a particular culture in which there is (or was) in place a very rigid moral framework, the kind of objective foundation that I’ve been saying is missing from these characters’ lives. The sword represents for Butch what the Biblical passage does for Jules: a glimpse beyond transient pop culture, a glimpse beyond the yawning abyss of nihilism to a way of life, a manner of thinking, in which there are objective moral criteria, there is meaning and value, and in which language does transcend itself.

Butch’s Paternal Line

In contrast to the (foreign) Samurai sword, the gold watch is a kind of heirloom that’s passed down in (American) families. It represents a kind of tradition of honor and manhood. But let’s think about how the watch gets passed down in this case. Butch’s great-grandfather buys it in Knoxville before he goes off to fight in World War I. Having survived the war, he passes it on to his son. Butch’s grandfather then leaves it to his own son before he goes into battle during World War II and is killed. Butch’s father, interned in a Vietnamese prisoner of war camp, hides the watch in his rectum, and before he dies—significantly—from dysentery, he gives it to his army comrade (Christopher Walken) who then hides it in his own rectum. After returning from the war, the comrade finds Butch as a boy and presents him with the watch. The way in which Butch receives the watch is of course highly significant. His father hides it in his rectum. The watch is a piece of shit; or, in other words, it is an empty symbol. Why empty? For the same reason that the Biblical passage was meaningless: it is a symbol with no referent. That to which it would refer is missing.

The sword is also significant because it, unlike the gold watch (an heirloom sent to Butch by a long-absent father, whom he little remembers), connects Butch to the masculine line in his family. The men in his family were warriors, soldiers in the various wars. Choosing the sword transforms Butch from a pugilist, someone disconnected who steps into the ring alone, into a soldier, a warrior, one who is connected to a history and a tradition, and whose actions are guided by a strict code of conduct in which honor and courage are the most important of values.

Note also how Butch is always returning. He seems doomed to return, perhaps to repeat things, until he gets it right. He must return to his apartment to get his watch. This return is associated with his decision to become his enemy. There’s his return to the cellar to save Marsellus, when he transcends his situation and begins to grasp something beyond the abyss. There’s also his return to Knoxville. Recall that the watch was originally purchased by his great-grandfather in Knoxville, and it is to Knoxville that Butch has planned to escape after he doesn’t throw the fight. After he chooses the sword and saves Marsellus, Butch can rightfully return to Knoxville, now connected to his paternal line, now rightfully a member of the warrior class.

Note finally that Butch’s transformation is signified by the motorcycle—excuse me, chopper—which he steals from Zed, and on which he and Fabienne (Maria de Medeiros) make their escape to Knoxville. The chopper is named “Grace,” indicating that Butch has at last found his redemption.

See Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Madman,” section 125 in The Gay Science, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1974) p. 181.

Actually, Nietzsche means something broader than this: by saying that God is dead, he means that any notion of objective, absolute values or truth is lost, not just those inherent to Judeo-Christianity, but it is the latter which concerns Tarantino, so I’m restricting my discussion to it.

With one very important exception, to be noted below.

The quote is a paraphrase of the Biblical passage and comes from the Sonny Chiba movie, The Bodyguard (1973). Chiba’s version ends: “And you will know my name is Chiba the Bodyguard when I lay my vengeance upon thee.”

All the passages I cite here are directly from Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994).

Cinematically, the briefcase is a reference to Robert Aldrich’s classic noir, Kiss Me Deadly (1955), in which the characters (notably the protagonist, Mike Hammer) chase after a box which contains some mysterious, glowing contents, believing it to be wildly valuable. Ironically, it turns out to be radioactive material, and once released it unleashes an apparent nuclear holocaust.

I wish to thank Lou Ascione and Aeon Skoble, who helped me clarify and refine my ideas about the film in discussions we’ve had.

Earlier versions of this essay appeared in Philosophy Now (No. 19, Winter 1997/98), and on metaphilm.com: http://metaphilm.com/philm.php?id=178_0_2_0.

[contact-form]

September 15, 2014

Shakespeare, Bitches!

By popular demand on Twitter I started posting again Shakespeare quotations with a small addition: the word “bitches” at the end. (At least somebody besides me finds this funny…)

Below are some of the recent offerings. Enjoy!

Bitches!

“Screw your courage to the sticking place, bitches.”

“Our little life is rounded with a sleep, bitches.”

“Love comforteth like sunshine after rain, bitches.”

“The croaking raven doth bellow for revenge, bitches.”

“Love is a devil, bitches.”

“Life’s but a walking shadow, bitches.”

“Lovers and madmen have such seething brains, bitches.”

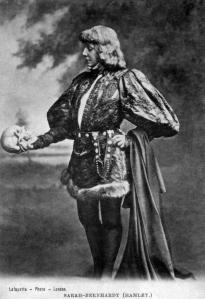

The Bard himself

“What’s past is prologue, bitches.”

“Cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war, bitches.”

“Ignorance is the curse of God, bitches.”

“I have Immortal longings in me, bitches.”

“Now the hungry lion roars, bitches.”

“Where’s my serpent of old Nile, bitches?”

“I could have better spared a better man, bitches.”

“What light through yonder window breaks, bitches?”

“Come not between the dragon and his wrath, bitches.”

“The prince of darkness is a gentleman, bitches.”

“I am not in the roll of common men, bitches.”

Guy talking to a skull

“While you live, tell truth, and shame the devil, bitches.”

“Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows, bitches.”

“There are few die well that die in a battle, bitches.”

“We cannot hold mortality’s strong hand, bitches.”

“It is war’s prize to take all vantage, bitches.”

“Beauty provoketh thieves sooner than gold, bitches.”

“Nature teaches beasts to know their friends, bitches.”

“Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall, bitches.”

Liz Taylor as Cleopatra

“We have some salt of our youth in us, bitches.”

“Tis pity Love should be so tyrannous, bitches.”

“A man I am, cross’d with adversity, bitches.”

“Come not within the measure of my wrath, bitches.”

“Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage, bitches.”

“As flies to wanton boys, are we to the gods, bitches.”

“Sail like my pinnace to these golden shores, bitches.”

“Thou art the Mars of malcontents, bitches.”

“So quick bright things come to confusion, bitches.”

“I’ll speak in a monstrous little voice, bitches.”

“A lion among ladies is a most dreadful thing, bitches.”

[contact-form]

September 7, 2014

Inspirational Quotes and Shit Volume III

I went on a mission a while back to try to expose just how banal inspirational quotes are. My most successful effort was to add “and shit” to the end of traditional quotations. E.g., “Religion is the opiate of the masses, and shit.” (Marx)

In no way did this motivate people to stop and think about the banality of what they were doing in posting quotes, but it was a lot of fun.

So I’ve put together a third partial list of the “and shit” quotes that I’ve posted on Twitter. (Click here for the first list, and here for the second.)

I always add a comma before the “and shit” to mark the end of the actual quote, whether that comma is actually needed or not.

Enjoy!

AND SHIT!

“If a story is in you, it has to come out, and shit.” (William Faulkner) #AndShit.

“Creativity takes courage, and shit.” (Matisse) #AndShit.

“Art does not reproduce what we see. It makes us see, and shit.” (Paul Klee) #AndShit.

“All truth is a species of revelation, and shit.” (Coleridge) #AndShit.

“Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth, and shit.” (Thoreau) #AndShit.

“Go to heaven for the climate and hell for the company, and shit.” (Twain) #AndShit.

“There is nothing on this earth more to be prized than true friendship, and shit.” (Aquinas) #AndShit.

“Music, to create harmony, must investigate discord, and shit.” (Plutarch) #AndShit.

“God is dead, and shit.”

Nietzsche

“War is the father of all, and shit.” (Heraclitus) #AndShit.

“I quickly laugh at everything for fear of having to cry, and shit.” (Beaumarchais) #AndShit.

“Art is the imposing of a pattern on experience, and shit.” (Whitehead) #AndShit.

“Become the one you are, and shit.” (Pindar) #AndShit.

“It is the destiny of the weak to be devoured by the strong, and shit.” (Bismarck) #AndShit.

“For me, my thoughts are my prostitutes, and shit.” (Diderot) #AndShit