Mark T. Conard's Blog, page 7

June 25, 2014

Logic Part II: Answer Key

In my last post, I discussed how to evaluate arguments. At the end of that piece I provided some examples of formal and informal arguments. Below is the answer key for those examples.

FORMAL AND INFORMAL ARGUMENT EXAMPLES

Identify which of the following is a formal and which is an informal argument. Can you tell which of the formal arguments are valid and which are invalid?

1. Mary is sulking, and she skipped dinner. I bet she’s depressed again. [Informal]

2. Frogs are amphibians, and amphibians are vertebrates, so frogs are vertebrates. [Formal, valid]

3. All Marxists are socialists, so all socialists are Marxists. [Formal, invalid]

4. The trashcan is turned over, the garbage is everywhere, and I see paw prints. The dog must’ve gotten into the trash. [Informal]

5. If it rains, Ronny takes the bus, and I know he took the bus, so it must be raining. [Formal, invalid]

6. Rex is a dog, and no dogs can solve logic problems, so Rex can’t solve logic problems. [Formal, valid]

7. If it rains, Ronny takes the bus, and it’s not raining, so he must not be taking the bus. [Formal, invalid]

8. ‘Neo’ is the hacker alias of Thomas Anderson, and ‘Neo’ is an anagram of ‘One.’ An anagram is a word that’s produced by rearranging the letters of a different word. [Not an argument!]

9. George can’t be that serious about Sally. If he were, he’d quit messing around with Angela, and I saw the two of them heading into the Motel 6 last night. [Formal, valid]

10. Ethel is a monstrously big woman, and she does have a beard, so she really ought to join the circus. [Informal]

[contact-form]

June 22, 2014

Logic Part II: Evaluating Arguments

After a Twitter exchange with a someone who was particularly challenged with regard to logic, I promised to post some basic lessons in logic (I’ve been teaching the subject for many years).

Part I began with a basic discussion of the nature of argumentation, which is one of the primary ways in which reasoning operates: it makes connections between statements. In this post, I talk about the criteria for evaluating arguments.

(And apologies for getting into teacher mode here…)

Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes. “Elementary…”

EVALUATING ARGUMENTS

There are two criteria for evaluating arguments:

A) Whether the premises support the conclusion;

B) Whether the premises are true.

A) WHETHER THE PREMISES SUPPORT THE CONCLUSION

Because there are two different types of arguments (see Part I), there are two different ways of talking about the first criterion.

I. With FORMAL ARGUMENTS, we talk about VALIDITY: In a valid (formal) argument, the premises really do establish the conclusion. If the premises are true, the conclusion has to be true.

EXAMPLES

These are VALID formal arguments:

1) “Socrates is a man, and all men are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.”

2) “If it’s raining, then my car is wet. My car’s not wet, so it’s not raining.”

In both cases, if the premises are true, the conclusion is guaranteed to be true.

This is an INVALID formal argument:

“If this is Tuesday, then we have logic class; it’s not Tuesday, so we don’t have logic class.”

The conclusion doesn’t follow from these premises. (Think for a minute about how this differs from the similar argument above about my car being wet.)

II. With INFORMAL ARGUMENTS, we talk about LOGICAL STRENGTH: A logically strong (informal) argument is one in which the premises tend to support the conclusion; they tend to establish the conclusion with a high degree of probability.

EXAMPLE

“Jones has been polling well, he has a clear message, he knows how to connect to his constituents, and his opponent has made some serious gaffs, so Jones will likely win the election in November.”

These premises provide support for the conclusion that Jones will win the election, but they certainly don’t guarantee that conclusion. The premises could all turn out to be true, and Jones could still lose.

Please note that the two criteria above (whether the premises support the conclusion, and whether the premises are true) are two very different things: Untrue or even absurd premises can provide very good support for a conclusion; and clearly true premises can fail to establish the conclusion.

Examples:

“If this is Tuesday, then the moon is made of green cheese. This is Tuesday, so the moon is made of green cheese.”

Note that this argument is valid: if the premises are true, then the conclusion has to be true. But the first premise is absurd.

“New York is comprised of five boroughs, it has a rich and varied history, and the mayor’s name is Bill, so it’s an ideal place to start a business.”

In this case, the premises are true, but they have no bearing on the conclusion. This is an example of a non sequitur fallacy (which I’ll discuss in the next post).

B) WHETHER THE PREMISES ARE TRUE

I’ll break this down into three parts:

I. From the logician’s point of view.

Logicians are concerned with the formal structure of arguments; that is, they want to know what kinds of statements follow from what other kinds of statements. So they’re not concerned about whether the statements themselves are true. That’s why in considering arguments, logicians symbolize the arguments. They take out the natural language.

Take the above example:

“If this is Tuesday, then the moon is made of green cheese. This is Tuesday, so the moon is made of green cheese.”

Let P = “This is Tuesday” and Q = “The moon is made of green cheese.”

Then the argument form would be (the line separates premises from conclusion):

If P, then Q

P_______

Therefore Q

We can then devise a test to determine whether this argument is valid (and it clearly is). So, interestingly, whatever propositions we plug in for P and Q, the conclusion will always follow.

Also take the invalid example above:

“If this is Tuesday, then we have logic class; it’s not Tuesday, so we don’t have logic class.”

This time let P = “This is Tuesday,” and Q = “We have logic class.”

Then the form of the argument would be:

If P, then Q

Not P

Therefore Not Q

This is an example of a formal fallacy, so no matter what we fill in for P and Q, the conclusion just doesn’t follow. (If we ONLY had logic class on Tuesday, then the argument would work; but of course we can have logic class on other days as well, so just because it’s not Tuesday, it doesn’t follow that we don’t have logic class.)

Only half Vulcan, but oh so logical.

II. From an everyday point of view.

Premises come in varying degrees of concreteness or abstraction. Something like “New York is comprised of five boroughs” is a very concrete statement of fact and is easily verified (we could just look at a map or call City Hall).

Other premises are more abstract, those dealing with political, religious, or philosophical matters, for instance. These are likely to be more controversial, and some of them may need to be established via argumentation.

Claims like “democracy is the best form of government,” “God is the cause of everything,” or “human actions are determined” are more abstract and more difficult to establish. (That doesn’t mean that they’re merely matters of opinion; claims, even very abstract ones, can be better and worse supported by argument and evidence.)

So, in general, we all know how to verify concrete statements; and the more abstract a statement, the more likely it will be that it will need to be supported with further argumentation if we wish to use it in an argument.

III. From a philosophical point of view.

I only mention this in passing, but the branch of philosophy that’s concerned with knowledge, belief, truth, etc., is epistemology. And from a philosophical point of view, the question of how we know certain propositions to be true—how it is that we’re acquainted with facts about the world—is of great importance and of equally great difficulty.

This gets us into very involved and interesting questions about how our minds work, how perception works, and how we understand and perceive the world and facts about the world.

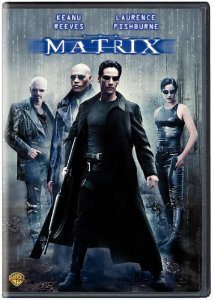

After all, we could be trapped in The Matrix…

FORMAL AND INFORMAL ARGUMENT EXAMPLES

Identify which of the following is a formal and which is an informal argument. Can you tell which of the formal arguments are valid and which are invalid?

1. Mary is sulking, and she skipped dinner. I bet she’s depressed again.

2. Frogs are amphibians, and amphibians are vertebrates, so frogs are vertebrates.

3. All Marxists are socialists, so all socialists are Marxists.

4. The trashcan is turned over, the garbage is everywhere, and I see paw prints. The dog must’ve gotten into the trash.

5. If it rains, Ronny takes the bus, and I know he took the bus, so it must be raining.

6. Rex is a dog, and no dogs can solve logic problems, so Rex can’t solve logic problems.

7. If it rains, Ronny takes the bus, and it’s not raining, so he must not be taking the bus.

8. ‘Neo’ is the hacker alias of Thomas Anderson, and ‘Neo’ is an anagram of ‘One.’ An anagram is a word that’s produced by rearranging the letters of a different word.

9. George can’t be that serious about Sally. If he were, he’d quit messing around with Angela, and I saw the two of them heading into the Motel 6 last night.

10. Ethel is a monstrously big woman, and she does have a beard, so she really ought to join the circus.

(Answers to follow)

[contact-form]

June 18, 2014

Logic Part I: Answer Key

In my previous post, I discussed some of the basics of argumentation, the study of which is known as Logic. I’m posting here the answer key to the examples at the end of that last discussion. The conclusions are underlined, and the indicator words are in bold. I label the types of indicator words in brackets at the end of the example.

1. California is more populous than New York; New York is more populous than Ohio; therefore, California is more populous than Ohio. [Conclusion indicator]

2. He won’t be driving recklessly, for he only does that when he’s upset, and he’s not upset. [Premise indicator]

3. Bill’s in trouble. He shot a deer, and they’re not in season. [No indicator words]

4. Toward evening, clouds formed and the sky grew darker; then the storm broke. [Not an argument.]

5. Since all seniors are immodest, and all arrogant people are immodest, all seniors are arrogant. [Premise indicator]

6. Lincoln could not have met Washington. Washington was dead before Lincoln was born. [No indicator words]

7. Terry, Sherry and Barry were all carded at JJ’s, and they all look as though they’re about thirty. Chances are I’ll be carded too. [No indicator words]

8. Jones won’t plead guilty to a misdemeanor, and if he won’t plead guilty, then he’ll be tried on a felony charge. Therefore, he’ll be tried on a felony charge. [Conclusion indicator]

9. I guess he doesn’t have a thing to do. Why else would he waste his time watching daytime TV? [No indicator words]

10. Some pesticides must be unsafe for humans to consume, since some pesticides are toxic, and whatever is toxic is unsafe for most humans to consume. [Premise indicator]

[contact-form]

June 15, 2014

Logic Part I: The Nature of Argumentation

After a Twitter exchange with a someone who was particularly challenged with regard to logic, I promised to post some basic lessons in logic (I’ve been teaching the subject for many years).

I begin with a basic discussion of the nature of argumentation, which is one of the primary ways in which reasoning operates: it makes connections between statements.

(And apologies for getting into teacher mode here…)

Aristotle founded the discipline of Logic

ARGUMENTATION

Argumentation is the method of Philosophy, and Logic is the science of argumentation. To make an argument is to provide reasons (the premises) in support of a claim (the conclusion).

Examples:

1) Berger is innocent, because the killer would have had blood all over him, and there wasn’t a drop of blood on Berger that night.

2) Mr. Conners, the gentleman who lives on the corner, comes down this street on his morning walk every day, rain or shine. Consequently, something must have happened to him, since he has not shown up today.

In example 1, the conclusion is “Berger is innocent.” The proof for this, the reasons provided, are the other two propositions: “The killer would have had blood all over him,” and “there wasn’t a drop of blood on Berger that night.”

In example 2, the conclusion is “something must have happened to [Mr. Connors].” How do we know this? What’s the proof? Well, the other two statements: “Mr. Connors comes down this street on his morning walk every day…” and “he has not shown up today.”

NOTE: Arguments are provided for claims/statements that need to be proved or demonstrated. Plain matters of fact, statements that are obviously true, those that can be verified through sense experience—these do not need to be argued for. “I am wearing shoes,” for example, doesn’t need to be argued for, since it can easily be verified simply by looking at my feet.

TWO KINDS OF ARGUMENTS

There are two kinds of arguments, formal and informal arguments (and thus two branches or subcategories of Logic). In a formal argument, we are trying to establish that the conclusion is necessarily true, that it can’t possibly be false. In an informal argument, we’re trying to establish that the conclusion is probably true.

Examples of Formal Arguments:

1) Every student who made 90 percent or better on the midterms has already been assigned a grade of A. Margaret already has her A, for she made 94 percent on her midterms.

2) If Congressman Smith were honest, he wouldn’t have taken bribes and lied about it; but he did take bribes and lie about it, so he’s definitely not honest.

In these examples I’m not trying to argue that Margaret probably got an A in the class or that Congressman Smith is likely dishonest. I’m arguing that these are necessarily the case. In each argument, if the premises are true, then the conclusion has to be true: If it’s true that “every student who made 90 percent or better on the midterms has already been assigned a grade of A,” and it’s true that Margaret “made 94 percent on her midterms,” then it has to be true that she’s getting an A.

Examples of Informal Arguments:

1) Sarah studies hard, and she’s bright, so she’s bound to do well in the class.

2) It’s likely going to rain: the barometer is falling and storm clouds are moving in from the west.

In example 1, the conclusion, “Sarah is bound to do well in the class” is supported by the two premises, but the premises don’t guarantee the truth of the conclusion. For example, other factors might come into play that prevent her from doing well. Likewise, in example 2, the premises provide support for the conclusion, they make it probable that the conclusion is true; but the conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow from the premises.

IDENTIFYING ARGUMENTS

It’s important for us to be able to identify arguments, to know when evidence is being given in support of a claim. This, for example, is not an argument:

‘Neo’ is the hacker alias of Thomas Anderson, and ‘Neo’ is an anagram of ‘One.’ An anagram is a word that’s produced by rearranging the letters of a different word.

No claim is being put forward; nothing is being proved here. This is simply a description, and not an argument.

Fortunately, we often have indicator words to tell us that we’re in the presence of an argument. There are both premise and conclusion indicators:

Premise Indicators

Since

Because

For

Given that

Assuming that

Conclusion Indicators

Therefore

Thus

So

Consequently

Hence

Berger is innocent, because the killer would have had blood all over him, and there wasn’t a drop of blood on Berger that night. (Premise indicator)

Sarah studies hard, and she’s bright, so she’s bound to do well in the class. (Conclusion Indicator)

Every student who made 90 percent or better on the midterms has already been assigned a grade of A. Margaret already has her A, for she made 94 percent on her midterms. (Premise Indicator)

Mr. Conners, the gentleman who lives on the corner, comes down this street on his morning walk every day, rain or shine. Consequently, something must have happened to him, since he has not shown up today. (Conclusion Indicator, Premise Indicator)

NOTE: Just because you find an indicator word doesn’t mean that you are looking at an argument; and just because you don’t find an indicator word doesn’t mean you’re not looking at an argument.

Examples:

Ever since he was little, Billy wanted to be a notary public, even though he doesn’t know what it is.

Not an argument: “since” here is not an indicator.

Martha must be depressed again. She only eats a lot when she’s depressed, and I just saw her wolf down three cheeseburgers.

This is an argument, even though there are no indicator words. “Martha must be depressed again” is the conclusion. The other two statements are the premises.

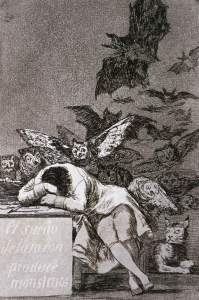

Francisco de Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

IDENTIFYING ARGUMENTS EXAMPLES

See if you can identify the premise and conclusion indicators in the following, then determine whether or not the example expresses an argument. Find the final conclusion, if it is an argument.

1. California is more populous than New York; New York is more populous than Ohio; therefore, California is more populous than Ohio.

2. He won’t be driving recklessly, for he only does that when he’s upset, and he’s not upset.

3. Bill’s in trouble. He shot a deer, and they’re not in season.

4. Toward evening, clouds formed and the sky grew darker; then the storm broke.

5. Since all seniors are immodest, and all arrogant people are immodest, all seniors are arrogant.

6. Lincoln could not have met Washington. Washington was dead before Lincoln was born.

7. Terry, Sherry and Barry were all carded at JJ’s, and they all look as though they’re about thirty. Chances are I’ll be carded too.

8. Jones won’t plead guilty to a misdemeanor, and if he won’t plead guilty, then he’ll be tried on a felony charge. Therefore, he’ll be tried on a felony charge.

9. I guess he doesn’t have a thing to do. Why else would he waste his time watching daytime TV?

10. Some pesticides must be unsafe for humans to consume, since some pesticides are toxic, and whatever is toxic is unsafe for most humans to consume.

Answers will appear in a subsequent post.

[contact-form]

June 8, 2014

Narratives and Our Ways of Knowing Part III: Descartes and the Scientific Revolution

The question of knowledge is a very old problem, going back to the ancients. What we can know about the world, and how we know it, is a huge puzzle. Now, we all love to tell stories, to tell people about things that have happened to us—or even stuff that happened to others, if it makes for a good tale. More than that, story-telling seems to be hardwired in us. We have a deep need to construct narratives to make sense out of the world and our lives. So not only do we try to convey what we think we know through our stories, but those stories also reflect the issues and problems regarding our ways of knowing.

I’m going to write a series of posts concerning the history of story-telling and our problems concerning the ways of knowing. I’ll move from Plato to Medieval Christianity, then to Descartes and the Enlightenment, Nietzsche, then modernism and classic film noir, and finally postmodernism. I only intend to provide a sketch of these issues, so what I’ll say is greatly simplified.

Part III: Descartes and the Scientific Revolution

The contemporary philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre wrote an influential book a few decades ago that argued for a revived Aristotelian view of humanity and human virtues. In that book, After Virtue, MacIntyre referred to a human being (not inaccurately) as “a story-telling animal.” I think that description captures a lot about the kinds of creatures we are.

In any event, in MacIntyre’s characterization of human history, he argues (as I have in previous posts) that for a very long time our mythologies provided the overarching narratives by which we understood ourselves and the world. For a long time, the Homeric epics provided the mythology, and then came Christianity, which told a different but very compelling story. As I discussed in the last post in this series, the Christian mythology left us with a world shrouded in mystery, one we couldn’t really know, but it still provided us with a Big Story, that governing narrative to help us make sense of things.

The scientific revolution and modernity

But something quite dramatic happened in the Western world during the scientific revolution and the several centuries that followed. Science came onto the scene in a profound way and replaced mythology. This was rebirth from the mysteries of the Medieval period, an enlightenment following the Dark Ages. We could now, using reason and the senses and scientific method, understand the natural world—a world of which we became increasingly a part.

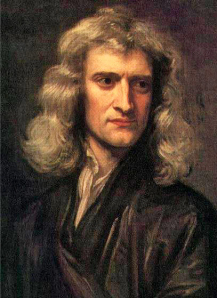

Sir Isaac Newton

Or, to put it another way, science was the story that rejected story-telling, at least for the purposes of understanding ourselves and the world.

The new story that science told was that nature is a completely rule-governed system operating according to necessary mechanical laws. When you put a ball on an inclined plank, it has to roll down, not because of magic or because some mysterious demon moved it; but because of the universal law of gravitation.

Further, nature is mathematically describable. That’s key, because it’s the coupling of science with mathematics that gives science its great descriptive and predictive capabilities. Math is the new engine driving science like a freight train.

Descartes

Descartes was a great mathematician and philosopher, and he was committed to the new science, to the picture of nature as a mathematically-describable and law-governed system. But he was also firmly committed to the view that human beings weren’t just a part of nature; we weren’t just animals. He believed we have minds that separated us from nature.

Rene Descartes

Descartes happened upon a groundbreaking discovery. When all else could be called into doubt, one thing was certain. Suppose, he says, there were an evil demon, a being like God, who’s all-powerful and all-knowing, but who’s malicious and who wants to deceive you at every instant of your life. Everything you think you believe, perceive, remember, all that you know about yourself and the world, could be a fiction.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, the eponymous matrix functions as a Cartesian evil demon. The computer system that keeps humanity in bondage has everyone plugged into a sophisticated computer program, fooling them into believing they know and understand the world and are living perfectly normal lives, when they’re only generating power for that system. (See my “The Matrix, The Cave, and the Cogito” in Steven M. Sanders’ The Philosophy of Science Fiction Film.)

The Matrix

So, given that we might be trapped in the matrix or fooled by some malicious god, is there anything left you can trust, anything you can know to be absolutely certain. Yes, there is. The evil demon could make you wonder whether you even exist, but in doubting your own existence, you thereby demonstrate that you do exist: “I think, therefore I am,” says Descartes.

I must exist in order to doubt that I exist, but what am I? What is this thing that doubts, wonders, thinks, believes, knows? I am a mind! In other words, says Descartes, I can doubt the existence of my physical body, but I can’t doubt the existence of my mind. Consequently, I am essentially a mind.

Further, says Descartes, I can now use this one absolutely certain bit of knowledge as a first principle, a rock-solid foundation upon which to build all my other knowledge. I can construct a complete metaphysics—a comprehensive knowledge of everything, including God—based on this one axiom.

Monads and Stories

So modernity rejects mythology and with it some grand overarching narrative with which to make sense of our lives. This goes hand-in-hand with Descartes’ metaphysics, since in his way of thinking, we become isolated minds (monads—simple, indivisible units) cut off from the rest of nature and the world, and indeed from any kind of Big Story about how things work.

Later on, empiricist philosophers like the great David Hume challenged Descartes’ claims to having necessary knowledge about the world. And a century or so after Hume, Nietzsche arrived on the scene, and things got really interesting.

(I’m indebted to my friend, Jerold J. Abrams’ essay, “A Homespun Murder Story”: Film Noir and the Problem of Modernity in Fargo,” which appears in my own The Philosophy of the Coen Brothers, for inspiration for this post.)

[contact-form]

Me and The Blues

As I said in my inaugural post, I’ll occasionally post here something about the blues (or music generally). I grew up first on the usual pop music, and then graduated to classic rock as a teenager. My introduction to straight blues was a real revelation, one of those life-transforming events. On a bit of a whim I picked a cassette of Muddy Waters out of one of those $1.99 bins at a record store (yes, a cassette; I’m that old). It was one of his late recordings, Hard Again, produced by the great Johnny Winter. The first track on it is Mannish Boy, and when I first popped it into the stereo and played it, I knew I’d found something very special. The music spoke to me in a way that few things previously had.

Anyway, fast forward a few decades. Now I play in a blues band in New York City. It’s for fun, and it’s the kind of situation where we play small clubs and often times to just a handful of people (or once in a while to an empty room). But the band is really good, and we have a great time playing.

We had a gig the other night at a place called Desmond’s Tavern. Below are some photos and some YouTube links to clips of some of the songs. The clips are brief, a minute and a half or so each, just the highlights.

Enjoy!

The 30th Street Blues Band Live at Desmond’s Tavern

The 30th Street Blues Band

Walking the Dog

By Rufus Thomas. It’s based on nursery rhymes: .

Bright Lights Big City

By the great Jimmy Reed, one of the most important blues song writers:

The great B.B. King.

Rock Me Baby

First recorded under this title by B.B. King, but based on earlier tunes, as so many classic blues songs were: .

Some guy playing guitar

Stormy Monday

The classic by T-Bone Walker. Our take on it is inspired largely by the Allman Brothers’ version: .

The one and only Muddy Waters

Got My Mojo Working

By Preston Foster, popularized by Muddy Waters: .

[contact-form]

June 4, 2014

#MakeKensDay: The Ken Mooney Book Bomb

Helping out a friend of a friend here. Let’s make Ken’s day.

Originally posted on Prose Before Ho Hos:

Originally posted on Prose Before Ho Hos:

Nicest Guy in the World

Hey folks, I want you to meet Ken Mooney. He’s the nicest guy in the world. Don’t believe me? Just check the dictionary. His picture is right there in black and white. Can’t miss it.

Ken is the author of the cracking-good Fantasy novel, Godhead, and is a lover of tattoos, comics, beards, and great music. I’m listening to one of his writing playlists right now on Spotify. It. Is. Epic.

By day, Ken masquerades as a TV ad-man, which is a fitting cover for the Nicest Guy on the Planet. By night, on weekends, and during official government holidays, he rips off his pinstripe suit and bowler hat and writes fiction that makes the gods weep. Literally.

I want you to meet Ken, because he’s my friend, and because for the last two weeks he’s had a bit of a rough spell. A fortnight ago he had a…

View original 490 more words

June 1, 2014

Narratives and Our Ways of Knowing Part II: The Middle Ages

The question of knowledge is a very old problem, going back to the ancients. What we can know about the world, and how we know it, is a huge puzzle. Now, we all love to tell stories, to tell people about things that have happened to us—or even stuff that happened to others, if it makes for a good tale. More than that, story-telling seems to be hardwired in us. We have a deep need to construct narratives to make sense out of the world and our lives. So not only do we try to convey what we think we know through our stories, but those stories also reflect the issues and problems regarding our ways of knowing.

I’m going to write a series of posts concerning the history of story-telling and our problems concerning the ways of knowing. I’ll move from Plato to Medieval Christianity, then to Descartes and the Enlightenment, Nietzsche, then modernism and classic film noir, and finally postmodernism. I only intend to provide a sketch of these issues, so what I’ll say is greatly simplified.

PART II: THE MIDDLE AGES

How the ‘Real World’ at last Became a Myth

HISTORY OF AN ERROR

1. The real world, attainable to the wise, the pious, the virtuous man—he dwells in it, he is it.

(Oldest form of the idea, relatively sensible, simple, convincing. Transcription of the proposition ‘I, Plato, am the truth’.)

2. The real world, unattainable for the moment, but promised to the wise, the pious, the virtuous man (‘to the sinner who repents’).

(Progress of the idea: it grows more refined, more enticing, more incomprehensible—it becomes a woman, it becomes Christian…)

–Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols (Hollingdale Translation).

THE FORM OF THE GOOD

In the first post in this series I talked about Plato’s Theory of Forms: the idea that there are real, abstract, non-physical entities that are the objects of necessary knowledge, and which we can know through intellectual intuition.

In Book V of his Republic, Plato discusses the “highest” Form, the Form of the Good. This Form acts as a first principle, says Plato, a rock-solid foundation for all our other knowledge. He describes the ascent of the philosopher to grasping the Good, as if he were scaling a mountain on the backs of his hypotheses and seeing the sun for the first time. Once having grasped that Form of the Good, the philosopher can make the return journey, demonstrating the truth of his original hypotheses, and thus completing a system of philosophical science, a complete knowledge of everything. (The cave allegory depicts this same journey, only using a different metaphor.)

Plato

At times, as in Republic V, Plato sounds oddly like a monotheist (which is peculiar for someone of his time), since one could interpret this discussion of the Form of the Good as a description of a mystical union with the divine. That’s not what Plato means, but his work was influential on early Christian thinkers; indeed, there’s a continuity between Platonism and Christianity. As Nietzsche quips, “Christianity is Platonism for ‘the people’” (Beyond Good and Evil).

For Plato, the Forms are intellectually accessible (at least to the philosopher). We can know the truth. And this is born out in the stories Plato tells. Socrates is on his search for the meaning of piety, justice, and so forth. One can live the good life, and the key to doing that is knowledge, knowledge that’s obtainable through a pure effort of reason.

CHRISTIANITY (OR WESTERN MONOTHEISM GENERALLY)

The big leap from Platonism to Christianity is the move from a realm of non-physical, abstract entities that are rationally intuitable to a transcendent, creator God who is not. There is still a big story, an over-arching narrative that governs the way we think about ourselves and the world. For Christianity, there is still a Truth (capital ‘t’), but it becomes shrouded in mystery, an object of faith. It’s a promise that’s left outstanding.

So Christianity (and monotheistic religions in general) poses a very great problem with regard to our ways of knowing. If God is the Truth, and God is transcendent (absent), then there is no real way to know. The nature of God himself, how God created everything, the nature of goodness, sin, redemption, virtue—all these things, unlike Plato’s Forms and Socrates’ virtues, are rationally unknowable and become objects of faith. (Why is there so much inter- and intra-religious squabbling over the exact meaning of these things if anyone can truly know them?)

The Crucifixion

Further, it’s a common understanding of things going back at least to Aristotle that to understand something, you have to know and understand the cause of that thing. So, to paraphrase Spinoza, if God is an absolutely infinite being separate from the universe and creator of that universe, then the universe itself is completely incomprehensible. That is, there’s no way to understand how God might have created the universe from a pure act of will and out of nothingness, so if he did, we have no hope of understanding reality.

(The nature of faith and it’s relation to knowledge is a huge topic, far too vast to deal with in any meaningful way here; I’m just giving a gloss on it to make my overall point. From Tertullian’s famous quote, “I believe it because it’s impossible,” to Aquinas’ theoretical arguments for God’s existence, it’s clear that knowledge is a big problem for theists.)

THE MIDDLE AGES

I’m not so much concerned with Christianity as I am with the Middle Ages, though the lives of people in Europe were dominated by religious thinking at that time. Further, I’m not qualified to talk about stories from the Middle Ages. I’m more interested in the stories we tell about that period.

Think, for example, of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). During an outbreak of plague, a knight is approached by death (black robe, scythe, all that) and told it’s his time. The knight challenges death to a game of chess for his life. It’s a stunning image, if you haven’t seen it: Max Von Sydow’s knight on a beach, sitting across the chess board from the black-hooded death. In any event, the overarching meta-narrative is in place: There is a Truth about the world and human existence, though it’s shrouded in mystery, and that mystery leaves our anxieties about our lives and our terrors about death intact.

Aquinas

The film version of Umberto Eco’s remarkable (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1986) isn’t necessarily an exception. William of Baskerville (an obvious reference to Sherlock Holmes) is superbly rational, a medieval sleuth who follows the evidence and uses his reasoning to solve the mystery of a series of murders. But the setting in which he finds himself, a 14th Century Benedictine Abbey, is filled with darkness and superstition. Yes, William solves the mystery, but he’s unable to save Aristotle’s lost treatise on comedy from the flames; and that work was the reason for the murders in the first place.

EPIC FANTASY

I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to say that many epic fantasy tales—I’m thinking of works like Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones—while set in alternate realities, are really based in the European Middle Ages. That is, the Middle Ages provide the backdrop or at least the starting point for these alternate worlds. This is clear from the state of technology: everyone rides horses; there is no electricity; everything is lit by torches; people wear armor and live in castles. (Plus, in the film/TV versions, all the characters have British accents.)

Knight and Dragon

This is the way we romanticize the Middle Ages: brave knights pursuing quests, and lovely Ladies in gowns chastely waiting for them, or else plotting intrigue back at the castle. But the fantasy element is in part provided by the addition of elements like dragons and magic (wizards in the case of LOTR; wogs and Melisandre the fire priestess in GoT). That is, it seems to feel quite natural to us to turn medieval life into fantasy, and precisely because of the darkness and mystery that envelopes that period.

So, again, we see that our ways of knowing (or of not knowing, in this case) filter into and are reflected by our narratives, the stories we tell.

[contact-form]

May 31, 2014

“Deconstruction” and its misuses (and, yes, Nietzsche)

I’ve recently seen on Twitter and in blogs several misuses of the word “deconstruction.” I knew my students didn’t really understand that term; but now I realize the misconception is more wide-spread than that. In the instances where I’ve seen it misused, people are treated it as a synonym for “analysis,” which means to break down, take apart, and examine. That’s not what “deconstruction” means.

The term was coined by the French theorist Jacques Derrida, and it’s come to mean various things to all the little Derridians following in his wake. To give two examples (and this is not meant to be exhaustive or definitive), it can mean to take a theory or a concept and expose the political or philosophical baggage at its heart; it can also mean to (attempt to) show that language is only ever self-referential, that it has no reference to anything beyond itself.

Nietzsche

Myself, I never had much use for deconstruction, but that way of theorizing has its roots in Nietzsche, and as you can probably tell if you’ve read my other posts, Nietzsche is a go-to guy for me. Now, Nietzsche believed that some of our traditional ways of understanding ourselves and guiding our lives—those perpetuated as religion, metaphysics, ethics, for example—were dangerous. So he wanted to undermine them.

But how do you do that? How do you take that which people hold dearest to themselves, that which they believe to be god-given, or ennobling, and convince them that it’s unnatural and life-denying? He seemed to think that straight-forward claims and arguments wouldn’t be effective; they’d fall on deaf ears.

So he ingeniously devised a way to show (or at least argue) that certain ideas or concepts in religion or metaphysics or ethics were inseparable from cruelty, savagery, violence—the things those very same traditional people would find abhorrent.

Just one example. In his brilliant On the Genealogy of Morals, he argues that the notion of guilt, which is central to our sense of ourselves as ethical beings, arose out of our history of taking pleasure in making suffer those who have reneged on their debts. (He employs here his training in philology, the study of language and the roots of words.) Earlier in our history, when someone owed us something and failed to pay, we were allowed by law to inflict pain upon that person, and precisely for the pleasure we would take from doing so. That idea and practice, Nietzsche claims, emerges eventually as our notion of guilt (which is synonymous with debt).

So, you see, this is an early example (or a proto-example) of what you might call “deconstruction”: Nietzsche details the history of a concept in order to expose what’s hidden and implied in its roots.

So please stop using “deconstruction” as a synonym for “analysis,” unless you really do mean to deconstruct Twitter trends or how to write a compelling email to a prospective agent.

[contact-form]

May 25, 2014

A Frank Koenig Story: “The Stolen Car”

Frank’s partner, Carl Gibson, had a large waistband and chubby cheeks, with his hair cut into a dirty blond flattop. He wore a cheap Sears and Roebuck suit with a white shirt and a chocolate striped tie. He always smelled of Aqua Velva.

Carl sat behind the wheel of his new De Soto, a pale green De Luxe Business Coupe, and Frank occupied the passenger’s seat, staring out the window.

He and Frank hadn’t been partners long. They worked out of the Major Case Squad and had caught a call that morning.

“Did you check out the name of the lady filing the complaint?” said Carl as he drove.

Frank shook his head.

“Didn’t you wonder why we’re handling a stolen car? Does that sound like a major case to you? Sure doesn’t to me. Should be uniforms handling it, but they’re not. They kicked it up to us.”

Frank continued to peer out the window at the concrete and steel buildings and the men in suits on their way to work. Here and there a mother pushed a stroller, or a couple of school kids hurried to get to their lessons.

“Just guess who it is,” said Carl with a sniff. “Who’s got that kind of juice to get us assigned to a stolen car? You going to guess?”

“No,” said Frank.

“Dorothy Winthrop,” said Carl, looking over at him. “You know who she is, right?”

“I heard the name.”

“Yeah, how could you not, society dame like that, friend of O’Dwyer. Rich as Rockefeller, like the song says. You imagine? Some poor dumb mope steals a car, belongs to one of the richest dames in the city. Wow, is he up shit’s creek without a paddle. Sure wouldn’t want to be in his shoes.”

Frank rubbed his eyes and ran a hand over his crew cut. The night before he’d hung out at Minton’s Playhouse, listening to Kenny Clark’s band. Frank loved be-bop and frequented clubs in Harlem and on 52nd Street. He always stayed late at Minton’s to listen to the afterhours set and try to pick up one of the colored girls. He hadn’t gone home with anybody, but he still got to bed late and this morning he had a headache and his eyes burned.

Frank dug his pack of Lucky’s out of his pocket, shook one out, and lit it with his silver Zippo. He rolled the window down and blew out smoke.

“Use the ashtray, will you, Frank,” said Carl, pointing.

Frank tapped ash into it.

Carl took a deep breath and let it out with a slow hiss.

“So,” he said. “The wife’s been asking about you again. She’s curious, you know. You’re my partner, and she understands that’s a special relationship. We got each other’s back. So she wants to know about you. And, listen, Frank, she thinks it’s a little queer that you ain’t married. We don’t know nobody else around our age who ain’t never been married. I told her straight out, you’re a regular guy, a normal guy, don’t go in for any of that, you know, funny stuff. Hell, they wouldn’t have let you in the Army if you did. Anyway, she’s got this friend—”

“No,” said Frank.

“No, what?”

He took another long drag on the cigarette.

“No, I ain’t going on any blind date. I don’t want a fix up, so forget it.”

Carl shook his head.

“Okay, but she ain’t going to be happy about it.”

“She’ll get over it.”

“Let me ask you, Frank, you got yourself a regular girl, somebody you go steady with?”

“No.”

“Well, then, why don’t you meet the wife’s friend. Her name’s Jean, she’s a widow, husband killed in the war. She’s real pretty—”

“Just drop it, will you?”

He crushed out the cigarette.

“You know Frank, you’re kind of secretive. You don’t talk a whole lot, so it’s kind of hard to get to know you. Guys at the station wonder about you. I tell them you’re okay, but, brother, I don’t really know you that well myself.”

Carl pulled the car to the curb on East 71st Street and turned off the engine.

“You know that, right? You don’t talk a whole lot?”

Frank opened the door of the De Soto.

“Hadn’t noticed,” he said and climbed out.

A man in a khaki chauffeur’s uniform met them on the sidewalk in front of a four-story brownstone.

“Officers, I’m Mrs. Winthrop’s driver,” he said without offering to shake their hands. “I’m the one responsible for the car being stolen.”

“Detectives,” said Frank. “And how are you responsible?”

“I foolishly left the car parked on the street last night. Normally we leave it in a garage on Third Avenue, but yesterday I parked it here in front of the house, meaning to move it later in the day, but I got busy with other things and completely forgot about it.”

Frank looked up and down the block. Tall trees lined the street, expensive cars sat parked along the curb, and rich people lived in the homes. Guys like Frank wouldn’t ever be invited inside one of these brownstones except on business.

“Did anybody see anything?” said Frank.

“Oh, we know who did it, who stole the car.”

“Yeah, who?” said Carl.

The driver shoved a piece of paper at him.

“A colored boy. Here’s his name and address. It’s way up town, but he works at that garage on Third Avenue I was just talking about.”

“How do you know he did it?” said Frank.

“Mrs. Winthrop had a—let’s say—a run-in with him the other day, and then the housekeeper saw him loitering on the block last night.”

“That’s it?” said Frank.

“Isn’t that enough to go on?”

“It’s a start,” said Carl. “But it doesn’t prove that he stole the car.”

“We’d like to speak with Mrs. Winthrop,” said Frank.

The chauffeur grimaced. “Are you sure that’s necessary? She’s in a really bad mood.”

“It’s necessary,” said Frank, pointing towards the house.

The three of them walked up onto the stoop and entered the foyer.

“Please wait here,” said the driver, and he walked off.

Old framed photos hung on the wall, an Asian carpet ran up the hallway, and a small marble-topped table by the front door held a basket of fruit.

“I’m afraid to touch anything,” said Carl, looking around.

Frank stood at the door, looking out into the street.

“Old broad’s got to pick her underwear out of her ass, just like anybody else,” he said.

He heard someone clear her throat, and turned to see a woman he assumed was Mrs. Winthrop, though she wasn’t old. She couldn’t have been more than forty-five, with blond coiffed hair, a tan skirt and stiff white blouse, and a giant diamond on her ring finger.

“I’m busy,” she said. “What do you want?”

“The driver says you had a run-in with someone at the garage,” said Frank.

“That’s correct, the boy who stole the car.”

“What sort of a run-in?”

She folded her arms. “He’s one of the car-washers there. He put a scratch in the paint of the Cadillac. I had Wilson drive me there, so I could chastise him for it.”

“What happened?”

“He denied that he did it, of course, and he became belligerent.”

“How do you know he did do it?”

“The scratch wasn’t there before Wilson took the car to be washed, and it was there after the boy washed it. What else am I to conclude?”

“Someone else in the garage scratched it, someone on the street scratched it, Wilson scraped against something while he drove it back here, Wilson’s lying. Should I go on?”

Carl gave him a nervous look and jumped in.

“Wilson said your housekeeper spotted the boy loitering in the neighborhood?”

“That’s right.”

“What was he doing?” said Frank.

“Loitering,” she said, giving him a severe look.

“Where exactly did she spot him?”

“On the sidewalk.”

“He was standing out on the sidewalk, doing what?”

“He wasn’t just standing out on the sidewalk,” she said. “He was walking by, looking at the house.”

“He was walking up the sidewalk?”

“That’s what I just said.”

“So he wasn’t loitering,” said Frank. “He walked up your block.”

“Loitering, walking, what difference does it make what you call it? He was monitoring the place. Why else would he be on my street?”

Frank looked at Carl, giving him a frown, and then turned back to Mrs. Winthrop.

“It’s a free country. He can walk up any sidewalk he wants to.”

“Be that as it may, there’s only one reason a miscreant like that would be in front of my house, and that’s to figure out how to take his revenge against me for our altercation.”

Frank pulled out his pack of cigarettes.

“You can’t smoke in here,” she said.

He put the pack away.

“We’ll look into what happened to your car,” he said, turning to leave.

“I demand that you arrest that boy,” she said, her voice strained.

“We’ll look into it,” said Frank, and he walked out.

When they climbed back in the car, Frank nodded at the slip of paper in Carl’s hand and said, “Let me see that.”

Carl handed it over, and Frank read. The name of the ‘boy’ was ‘Walter O’Neill’. Frank scratched his chin, staring at the piece of paper. One of the colored girls Frank saw on occasion, Carolina, had a younger half-brother by that name.

“Garage first?” said Carl.

“Yeah, pull around there. Let’s see if anybody’s available to answer questions.”

Carl made the turn onto 3rd Avenue, drove a block, and pulled into the garage entrance. They got out of the car.

“You go ahead and ask questions,” said Frank. He nodded at a pay phone. “I need to make a call.”

He stepped into the booth, closed the door, and pulled out his address book. He found Carolina’s number and dialed it. After the third ring, a woman answered.

“Hello Mrs. O’Neill, this is Detective Frank Koenig.”

Carolina’s mother knew about her relationship with Frank. Iris O’Neill didn’t approve of interracial mixing, but she didn’t seem to bear any ill-will towards Frank.

“Hello Detective.”

“May I speak to Carolina?”

“Little early for you to be calling.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

He heard her set down the phone, and in a moment Carolina came on the line.

“What you want, Frank? I got to get to work.”

“Your brother’s name is Walter, isn’t it?”

“Half-brother.”

“He washes cars at a garage on Third Avenue?”

He heard her breath catch. “Did something happen?”

“He’s okay, but he’s accused of stealing a car.”

“Shit, Frank.”

“Do you think he could’ve done it?”

She hesitated. “I’d like to say no. He’s foolish sometimes, but he ain’t outright stupid.”

“Okay. I’ll do my best to look out for him.”

“Thank you, Frank. I owe you one.”

He felt his pulse jump a beat. “I know a way you can repay me.”

“I bet you do,” she said, and he could hear the heat in her voice. It made him hard.

After they hung up Frank adjusted his erection through his trousers, and met Carl coming out of the garage.

“Come up with anything?” said Frank.

“The boy should be here any minute.”

“He’s almost thirty.”

Carl frowned. “So?”

“So don’t call him a boy.”

Carl shook his head.

“Anyway, the manager knew all about that squabble between O’Neill and Mrs. Winthrop. He said there wasn’t much to it. She came in, accused him of scratching the car, he denied it, she insisted, and he told her to go fuck herself under his breath.”

“That’s him getting belligerent?”

Carl nodded. “That was the extent of it, according to the manager.”

Frank looked up to see a young black man approaching. He wore dungarees and a red t-shirt, and had his hair cropped close. He looked more like Carolina’s brother Bobby than he did Carolina, but Frank could see the family resemblance.

A wary look came over his face as he approached the two of them.

“Cops, right?”

Frank flashed his badge.

“Detectives Koenig and Gibson,” he said.

“What do you want?”

“Tells us your where-abouts last night.”

O’Neill folded his arms.

“I worked until around eight, had a beer with a buddy, went uptown and shot some pool, then went home.”

“You got witnesses?” said Carl. “People can verify that?”

“My buddy and the cats I played pool with, for sure.”

“What were you doing on East Seventy-First Street last night?”

He shrugged. “I walked across Seventy-First to get the subway.”

“What time was that?” said Carl.

“Around nine, a little after.”

“You didn’t come back to this neighborhood after you went uptown?” said Frank.

He shook his head. “Nope. Ain’t been back until now.”

“Somebody stole the Winthrop’s Cadillac, the one that got scratched. You know anything about it?”

O’Neill folded his arms. “Not a thing. I didn’t have nothing to do with that.”

Frank looked at Carl.

“Let me talk to him a minute.”

Carl frowned. “We got to take him in. You heard what Mrs. Winthrop said.”

“Take a walk,” said Frank.

Carl hitched up his pants and shuffled over to the De Soto. Frank took a step closer to O’Neill, and motioned for him to turn away from Carl. They spoke in low voices.

“I know your half-sister,” said Frank.

O’Neill looked at him with raised eyebrows. “Shit, you’re the cop, the one she’s bedding?”

Frank nodded. “I told her I’d look out for you best I could. So if you know anything about this car getting stolen, you’d better tell me right now.”

O’Neill flared his nostrils, and his face became hard.

“I don’t know nothing,” he said.

Frank pulled out his pack of Lucky’s and offered one to O’Neill. O’Neill thought about it, and took the cigarette. Frank took one of his own and lit both of them with his silver lighter. He snapped it closed.

“Don’t be fucking stupid,” he said. “If you don’t cooperate, we’re going to have to bust you, and that’ll be the end of it. This lady’s got connections, knows people, including the Mayor. Don’t matter what evidence there is, you’ll get convicted and do hard time.”

“Shit, that ain’t fair.”

Frank laughed.

“Don’t be a goddamned child. ‘Course it ain’t fair, but that’s the way it is. The juice this Winthrop dame has, a white man would do time. What chance you think you got?”

“Lefty Grimes,” said O’Neill.

“What about him?”

“I don’t know for sure, but I heard he’s been boosting fancy cars in rich neighborhoods.”

Frank nodded. “Good. We’ll look into it. In the meantime, keep your nose clean, and don’t go mouthing off to any more rich white people.”

Carl didn’t kick up any more fuss over letting O’Neill go, since they had another lead to pursue.

“Who is he?” said Carl as he steered the car through traffic. “This Lefty Grimes.”

“Small-time hood,” said Frank. “Deals in marijuana, cocaine, and stolen goods.”

“Colored?”

“Yeah.”

“What’s he doing on the Lower East Side with all the immigrants and Jews?”

“Beats me.”

Grimes lived in a detached house with a garage just off Delancey Parkway, near the Williamsburg Bridge. Carl parked the car in front of a hydrant on the street, and he and Frank climbed up onto the stoop.

Carl raised his meaty fist to knock on the door, when Frank stopped him.

“You smell something?” he said.

Carl sniffed the air. “Like what?”

“Try again.”

Carl turned his head, sniffing. “Reefer.”

Frank nodded. “I’d call that ‘exigent circumstances’, wouldn’t you?”

“Hell, yeah.”

They drew their guns. Frank tried the doorknob and found it locked. He took half a step back, raised his foot, and kicked the door hard enough that the bolt tore through the wooden frame, and the door flew open with a bang.

They hustled into the living room to find two black men sitting on a sofa, one of them holding a makeshift pipe. The two men started to get up. An ashtray and a pistol sat on the table in front of them.

Frank and Carl pointed their guns.

“Hands up,” said Carl. “Now!”

They handcuffed Grimes and the other man, then searched the house to find stashes of money and reefer.

Carl stood guard over the suspects, while Frank exited the house to look through the garage. He rolled up the door with a clang. Two cars sat inside, one of them a burgundy Cadillac. He checked the right rear fender to find the scratch Dorothy Winthrop had described.

Frank returned to the living room. The two black men sat handcuffed on the sofa. Carl stood over them.

“The Winthrop’s Cadillac is in the garage.”

Carl let out a whistle. “This should win us a few points with that dame. And I guess this means O’Neill’s off the hook.”

Lucky Grimes let out an unpleasant chuckle. Frank looked over at him.

“You know something?”

“That O’Neill punk is the one who stole the fucking car.”

“You paid him to steal it?”

“Hundred dollars.”

Frank turned to Carl. “Take him outside,” he said, indicating Grimes’ partner.

Carl grabbed the guy by the arm, got him off the sofa, and led him out the door.

Frank drew his gun, stepped over, and pointed it at Grimes’ forehead.

“O’Neill didn’t have anything to do with this.”

“Say what?”

“You fucking heard me. You can take the whole rap, or you can pin it on some other punk. I don’t give a shit, only O’Neill wasn’t involved.”

“Whatever you say, detective.”

Frank pushed the gun barrel against his head, digging it into the skin, and pushing Grimes back against the cushion.

“Don’t fuck with me, shit bird. I find out you pinned this thing on O’Neill, and I’ll hurt you bad.”

“All right, all right. I got it,” said Grimes through clenched teeth. “He didn’t have nothing to do with it.”

Frank and his partner took the two men to the station and did the paperwork to put them in the system. Their Captain made a special trip to the squad room to congratulate them on wrapping up the case so fast.

That evening Frank sat in his Buick on 3rd Avenue just past 72nd Street, looking at the parking garage and smoking a cigarette. The sun had fallen behind the buildings and treetops. Shadows crept over the neighborhood.

An older man, dressed prissy in a trim jacket and slacks, passed on the sidewalk, and gave Frank the once-over.

Frank watched him to the corner, then looked back at the garage to see Walter O’Neill leaving the place. Frank tossed the butt. He climbed out of the car, drew his gun, and came up on O’Neill fast.

O’Neill’s eyes went wide, seeing Frank. He tried to backtrack, but Frank smashed him on the side of the head with the gun, and O’Neill fell backwards, stumbling onto the sidewalk. Frank bent down and grabbed him by the collar, threatening him with the pistol.

“Don’t ever make a jerk out of me again. Got it?”

O’Neill nodded, and blood ran from his scalp. Frank pushed the gun barrel into his neck.

“Tell me you understand.”

“I understand!”

Frank dropped him on the sidewalk. He holstered his gun and walked back to the car.

[contact-form]