Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 35

June 22, 2018

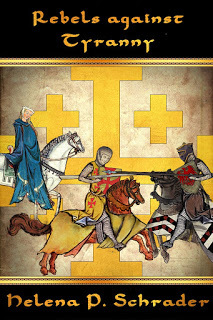

Cover Reveal: Rebels against Tyrrany

This week, the first book in my new series went to the publisher.

It seemed like a good opportunity to “reveal” the cover to future readers and discuss the process of cover design.

Covers can kill – novels, I mean. Nothing, studies have shown, is more influential in enticing a potential reader to pick up a book while browsing in a bookstore than an “attractive” cover – and nothing is more likely to put a potential reader off than a “bad” cover. A good cover will attract readers that would never buy the book based on subject, title or author, and a bad cover will make the very people who would love a particular book scorn it. Covers matter!

But -- aside from "attractive" being highly subjective -- being “attractive” isn’t enough.

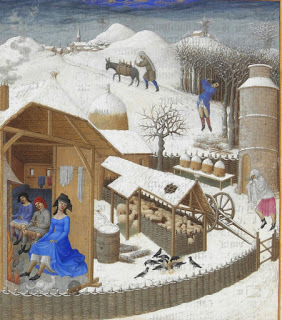

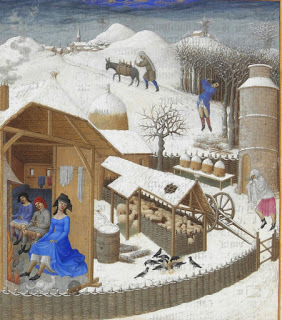

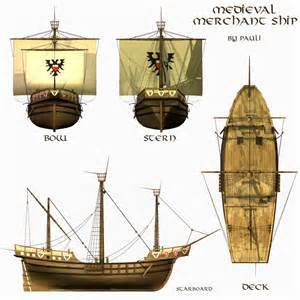

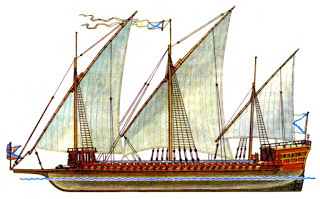

Beautiful -- but would it sell books?

Beautiful -- but would it sell books?

A cover that is “attractive” (even in the advertising sense of the word) may get a browsing reader to read the cover blurb, but if the picture has nothing to do with the content, they are likely to put the book down again. There is no point having a vampire or a half-naked woman on the cover of your book if the book isn’t about vampires or beautiful women in sexual situations.

When I first started publishing novels, I let the publisher design the cover, thinking they were the professionals and they would understand the market much better than I.

Big mistake.

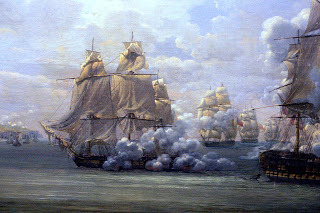

When it comes to historical fiction, it is vitally important to immediately evoke the time period of a novel because you discredit yourself instantly if you get it wrong. Publishers, however, are not historians. They don’t know the difference between 11th and 16th-century armor, or between a Spitfire and a Piper Cub. Crusaders in plate armor? I don't think so!

Crusaders in plate armor? I don't think so!

So I now “design” my own covers, by which I mean I select the overall thematic components, and then hire a professional graphic designer to do the fine work essential to make the image look as good as anything a major publishing house can produce.

Most "advice" I have read about selecting cover says: "look what everyone else in your genre is doing and copy them." Well, if I write what everyone else is writing and don't have anything new to add, then that the way my covers should indeed be designed. As a reader, if I see another cover with actors in period costumes with their heads cut off, I will feel nauseous and certainly NOT buy the book precisely because the cover looks like the last 13 million books that have been published.

As someone who values creativity in writing, I also value creative covers. I do not want my covers to look like every other historical fiction book that has been dumped on the market over the last 10 years. So, no headless actors in period costumes. No empty helmets. No cartoon characters leaning on their swords. (Why any self-respecting knight would blunt his sword tip by driving it into the ground and then leaning on it is beyond my low brain capacity.)

I wanted images that would look realistic yet could be composed to reflect the content. For the Jerusalem Trilogy, I also wanted the reader to get progressively closer to the main character. On the cover of the first book, Knight of Jerusalem, Balian is shown from the back quart and his face is mostly hidden by his helmet, while Jerusalem dominates the picture. In the second book, Defender of Jerusalem, he is charging at the reader, but still obscured by his helmet while Jerusalem is more distant, receding. In the third book, Envoy of Jerusalem, the reader finally sees Balian head on and Jerusalem is lost. Instead, Balian separates the antagonists Saladin and Richard the Lionheart, while the Christian captives being driven into slavery form the background.

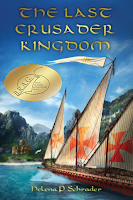

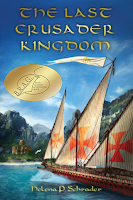

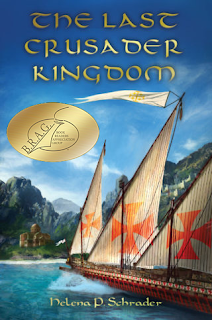

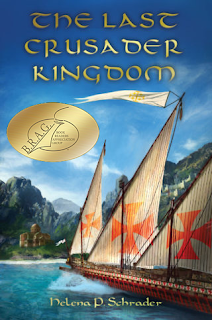

With the Last Crusader Kingdom, I sought to juxtapose Frankish secular power (represented by a castle) with Greek ecclesiastical power (represented by a Greek Orthodox church), and between them the symbol of change ― a fresh wind blowing ― in the form of a sailing ship bearing the crosses of Ibelin.

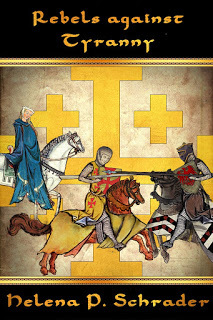

Now, however, I wanted a sharp change in style to signal that this is a new series, not just a continuation of the previous books (even if there is some overlap in characters!).

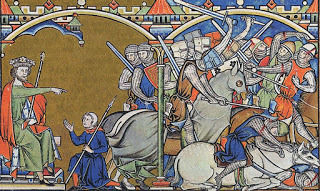

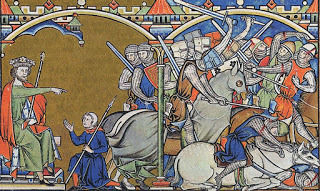

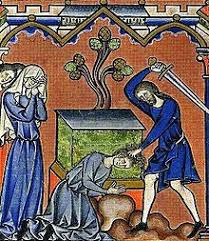

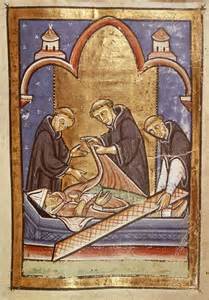

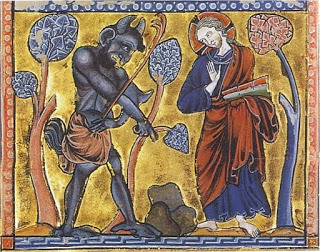

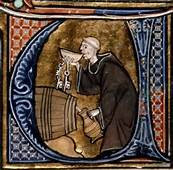

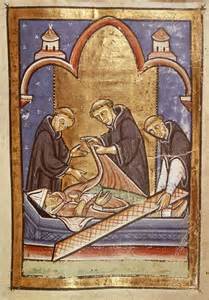

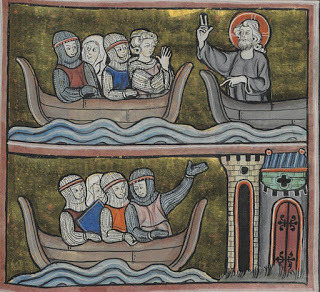

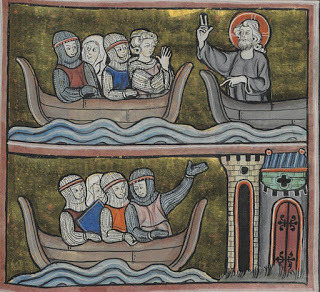

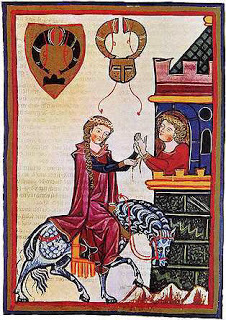

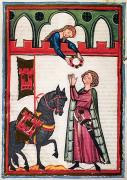

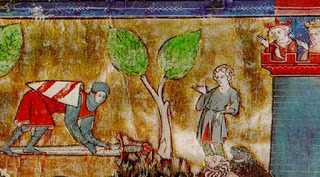

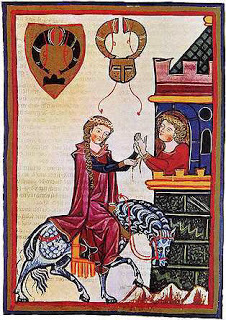

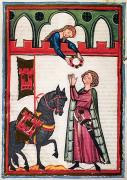

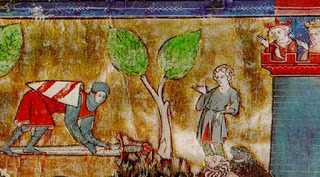

I wanted to connect with the period in which the book is set, the 13th century, by using images that remind the reader of the wonderfully evocative, colorful and often whimsical manuscript illustrations of the Middle Ages.

Indeed, I initially looked for real manuscript illustrations that might reflect the contents of the book. I experimented with using one of these, but the effect was something entirely too violent. (I also subsequently changed the title.)

So I ended up asking my amazing graphic designer to develop an “illumination” that was completely original. This had to show knights jousting (an important element of the plot) and it had to show an Ibelin taking on an Imperial knight (symbolical of their overall stance rather than an event), but it also had to hint at the love-story that is also an important aspect of this book. All without being too cluttered! The result:

The back cover, on the other hand, is devoted entirely to the relationship between the two main characters. Here's the back cover image without the text.

Next week I will open the cover to tell you more about the content of the novel. You can help me chose the back cover blurb, however, by taking part in a survey at: https://www.facebook.com/HelenaPSchrader/

Meanwhile, enjoy my published novels:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

It seemed like a good opportunity to “reveal” the cover to future readers and discuss the process of cover design.

Covers can kill – novels, I mean. Nothing, studies have shown, is more influential in enticing a potential reader to pick up a book while browsing in a bookstore than an “attractive” cover – and nothing is more likely to put a potential reader off than a “bad” cover. A good cover will attract readers that would never buy the book based on subject, title or author, and a bad cover will make the very people who would love a particular book scorn it. Covers matter!

But -- aside from "attractive" being highly subjective -- being “attractive” isn’t enough.

Beautiful -- but would it sell books?

Beautiful -- but would it sell books?A cover that is “attractive” (even in the advertising sense of the word) may get a browsing reader to read the cover blurb, but if the picture has nothing to do with the content, they are likely to put the book down again. There is no point having a vampire or a half-naked woman on the cover of your book if the book isn’t about vampires or beautiful women in sexual situations.

When I first started publishing novels, I let the publisher design the cover, thinking they were the professionals and they would understand the market much better than I.

Big mistake.

When it comes to historical fiction, it is vitally important to immediately evoke the time period of a novel because you discredit yourself instantly if you get it wrong. Publishers, however, are not historians. They don’t know the difference between 11th and 16th-century armor, or between a Spitfire and a Piper Cub.

Crusaders in plate armor? I don't think so!

Crusaders in plate armor? I don't think so! So I now “design” my own covers, by which I mean I select the overall thematic components, and then hire a professional graphic designer to do the fine work essential to make the image look as good as anything a major publishing house can produce.

Most "advice" I have read about selecting cover says: "look what everyone else in your genre is doing and copy them." Well, if I write what everyone else is writing and don't have anything new to add, then that the way my covers should indeed be designed. As a reader, if I see another cover with actors in period costumes with their heads cut off, I will feel nauseous and certainly NOT buy the book precisely because the cover looks like the last 13 million books that have been published.

As someone who values creativity in writing, I also value creative covers. I do not want my covers to look like every other historical fiction book that has been dumped on the market over the last 10 years. So, no headless actors in period costumes. No empty helmets. No cartoon characters leaning on their swords. (Why any self-respecting knight would blunt his sword tip by driving it into the ground and then leaning on it is beyond my low brain capacity.)

I wanted images that would look realistic yet could be composed to reflect the content. For the Jerusalem Trilogy, I also wanted the reader to get progressively closer to the main character. On the cover of the first book, Knight of Jerusalem, Balian is shown from the back quart and his face is mostly hidden by his helmet, while Jerusalem dominates the picture. In the second book, Defender of Jerusalem, he is charging at the reader, but still obscured by his helmet while Jerusalem is more distant, receding. In the third book, Envoy of Jerusalem, the reader finally sees Balian head on and Jerusalem is lost. Instead, Balian separates the antagonists Saladin and Richard the Lionheart, while the Christian captives being driven into slavery form the background.

With the Last Crusader Kingdom, I sought to juxtapose Frankish secular power (represented by a castle) with Greek ecclesiastical power (represented by a Greek Orthodox church), and between them the symbol of change ― a fresh wind blowing ― in the form of a sailing ship bearing the crosses of Ibelin.

Now, however, I wanted a sharp change in style to signal that this is a new series, not just a continuation of the previous books (even if there is some overlap in characters!).

I wanted to connect with the period in which the book is set, the 13th century, by using images that remind the reader of the wonderfully evocative, colorful and often whimsical manuscript illustrations of the Middle Ages.

Indeed, I initially looked for real manuscript illustrations that might reflect the contents of the book. I experimented with using one of these, but the effect was something entirely too violent. (I also subsequently changed the title.)

So I ended up asking my amazing graphic designer to develop an “illumination” that was completely original. This had to show knights jousting (an important element of the plot) and it had to show an Ibelin taking on an Imperial knight (symbolical of their overall stance rather than an event), but it also had to hint at the love-story that is also an important aspect of this book. All without being too cluttered! The result:

The back cover, on the other hand, is devoted entirely to the relationship between the two main characters. Here's the back cover image without the text.

Next week I will open the cover to tell you more about the content of the novel. You can help me chose the back cover blurb, however, by taking part in a survey at: https://www.facebook.com/HelenaPSchrader/

Meanwhile, enjoy my published novels:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on June 22, 2018 03:00

June 15, 2018

Defining Chivalry

Modern discussions about whether “chivalry is dead” often revolve around whether men should open doors for women. Yet such discussion demonstrate just how little is known and understood about the concept of chivalry today.

To be sure, chivalry defied definition even in the centuries where it was the dominant ethos of educated classes in Western Europe. The biographer of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights of the late 12th and early 13thcentury, a man who was often held up as a perfect chivalrous knight, himself asked “what is chivalry?”

His answer:

So strong a thing, and of such hardihood, and so costly in learning, that a wicked man or low dare not undertake it.

In this entry, I’d like to review what we do know about chivalry and the extent to which it influenced medieval society.

Chivalry evolved out of the military and literary traditions of antiquity, and emerged at the beginning of the High Middle Ages as a concept that rapidly came to dominate the ethos and identity of the nobility. Chivalry is inextricably tied to knighthood, a phenomenon distinct to Europe in the Middle Ages. There have been cavalrymen in many different ages and societies, but the cult of knighthood, including a special dubbing ceremony and a code of ethics, exists only in the Age of Chivalry -- roughly 1000 - 1450.

Chivalry was always an ideal. It defined the way a knight was supposed to behave. No one in the Middle Ages seriously expected every knight to live up that ideal, much less all of the time. Even the heroes of chivalric romances usually fell short of the ideal at least some of the time – and many only achieved their goal and glory when they overcame their baser instincts or their natural shortcomings to live, however briefly, like “perfect, gentle knights.”

In other words, chivalry was a code of behavior that young men were supposed to aspire to – not already have. The code was articulated and passed on to youths in the form of romances and poems lionizing the chivalrous deeds of fictional heroes. It was also recorded in the biographies of historical personages viewed as examples of chivalry, from William Marshal to Geoffrey de Charney and Edward, the Black Prince. Finally, there were a number of textbooks or handbooks that attempted to codify the essence of chivalry.

So what defined chivalry? First and foremost, a knight was supposed to uphold justice by protecting the weak, particularly widows, orphans, and the Church. He was also supposed to be upon a permanent quest for honor and glory, sometimes translated as “nobility.” The troubadours, meanwhile, had introduced for the first time the notion that “a man could become more noble through love.” Thus love for a lady became a central – if not the central – concept of chivalry, particularly in literature.

The chivalric notion of love was that it must be mutual, voluntary, and exclusive – on both sides. It could occur between husband and wife – and many of the romances such as Erec et Enide and Yvain, The Knight with the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes or Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzivalrevolve in part or in whole around the love of a married couple. But the tradition of the troubadours did put love for another man’s wife on an equal footing with love for one’s own – provided the lady returned the sentiment. The most famous of all adulterous lovers in the age of chivalry were, of course, Lancelot and Guinevere, closely followed by Tristan and Iseult.

The chivalric notion of love was that it must be mutual, voluntary, and exclusive – on both sides. It could occur between husband and wife – and many of the romances such as Erec et Enide and Yvain, The Knight with the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes or Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzivalrevolve in part or in whole around the love of a married couple. But the tradition of the troubadours did put love for another man’s wife on an equal footing with love for one’s own – provided the lady returned the sentiment. The most famous of all adulterous lovers in the age of chivalry were, of course, Lancelot and Guinevere, closely followed by Tristan and Iseult.

In more practical terms, one of the handbooks on chivalry written by the Spanish nobleman Ramon Lull lists the virtues of a knight as nobility, loyalty, honor, righteousness, prowess (courage), love, courtesy, diligence, cleanliness, generosity, sobriety, and perseverance. Wolfram von Eschenbach in Parzifal, on the other hand, stresses a strong sense of right and wrong, compassion for the unfortunate, generosity, kindness, humility, mercy, courtesy (particularly to ladies), and cleanliness.

Geoffrey de Charney, the French hero from the Hundred Years’ War, also wrote a handbook on chivalry that is particularly valuable because he was a man with a powerful reputation as a chivalrous knight. (He was killed at the Battle of Poitiers defending the French battle standard, the oriflamme.) Charney puts the emphasis on love as a spur to great deeds and stresses that a knight must love “loyally” (with exclusive devotion to his one true love), but includes good manners, generosity, humility, fortitude, and courage among the qualities of chivalry as well. As a reflection of his career, Charney places greater value on fighting – stressing its hardships, deprivations, and risks – over frivolous tournaments.

William Marshal’s biographer, on the other hand, writing in the early 13th century, sees in tournaments a means of giving men a chance to demonstrate their “worth” – i.e., their courage, audacity, and skill at arms. These are the skills, combined with unwavering loyalty to his liege, that enable Marshal to rise from landless knight to regent of England. While Marshal (or at least his biographer) put the emphasis on courage, the themes of courtesy and discretion with respect to ladies, and generosity, are also present.

Readers interested in learning more about this fascinating concept can turn to:

Bibliography

Barber, Richard W. The Knight and Chivalry. The Boydell Press, 1970, 1974, 1995.

Duby, George. 1985. William Marshal: The Flower of Chivalry. Random House, 1985.

Hopkins, Andrea. Knights: The Complete Story of the Age of Chivalry, from Historical Fact to Tales of Romance and Poetry. Quarto Publishing, 1990.

and many other sources!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

To be sure, chivalry defied definition even in the centuries where it was the dominant ethos of educated classes in Western Europe. The biographer of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights of the late 12th and early 13thcentury, a man who was often held up as a perfect chivalrous knight, himself asked “what is chivalry?”

His answer:

So strong a thing, and of such hardihood, and so costly in learning, that a wicked man or low dare not undertake it.

In this entry, I’d like to review what we do know about chivalry and the extent to which it influenced medieval society.

Chivalry evolved out of the military and literary traditions of antiquity, and emerged at the beginning of the High Middle Ages as a concept that rapidly came to dominate the ethos and identity of the nobility. Chivalry is inextricably tied to knighthood, a phenomenon distinct to Europe in the Middle Ages. There have been cavalrymen in many different ages and societies, but the cult of knighthood, including a special dubbing ceremony and a code of ethics, exists only in the Age of Chivalry -- roughly 1000 - 1450.

Chivalry was always an ideal. It defined the way a knight was supposed to behave. No one in the Middle Ages seriously expected every knight to live up that ideal, much less all of the time. Even the heroes of chivalric romances usually fell short of the ideal at least some of the time – and many only achieved their goal and glory when they overcame their baser instincts or their natural shortcomings to live, however briefly, like “perfect, gentle knights.”

In other words, chivalry was a code of behavior that young men were supposed to aspire to – not already have. The code was articulated and passed on to youths in the form of romances and poems lionizing the chivalrous deeds of fictional heroes. It was also recorded in the biographies of historical personages viewed as examples of chivalry, from William Marshal to Geoffrey de Charney and Edward, the Black Prince. Finally, there were a number of textbooks or handbooks that attempted to codify the essence of chivalry.

So what defined chivalry? First and foremost, a knight was supposed to uphold justice by protecting the weak, particularly widows, orphans, and the Church. He was also supposed to be upon a permanent quest for honor and glory, sometimes translated as “nobility.” The troubadours, meanwhile, had introduced for the first time the notion that “a man could become more noble through love.” Thus love for a lady became a central – if not the central – concept of chivalry, particularly in literature.

The chivalric notion of love was that it must be mutual, voluntary, and exclusive – on both sides. It could occur between husband and wife – and many of the romances such as Erec et Enide and Yvain, The Knight with the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes or Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzivalrevolve in part or in whole around the love of a married couple. But the tradition of the troubadours did put love for another man’s wife on an equal footing with love for one’s own – provided the lady returned the sentiment. The most famous of all adulterous lovers in the age of chivalry were, of course, Lancelot and Guinevere, closely followed by Tristan and Iseult.

The chivalric notion of love was that it must be mutual, voluntary, and exclusive – on both sides. It could occur between husband and wife – and many of the romances such as Erec et Enide and Yvain, The Knight with the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes or Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzivalrevolve in part or in whole around the love of a married couple. But the tradition of the troubadours did put love for another man’s wife on an equal footing with love for one’s own – provided the lady returned the sentiment. The most famous of all adulterous lovers in the age of chivalry were, of course, Lancelot and Guinevere, closely followed by Tristan and Iseult.

In more practical terms, one of the handbooks on chivalry written by the Spanish nobleman Ramon Lull lists the virtues of a knight as nobility, loyalty, honor, righteousness, prowess (courage), love, courtesy, diligence, cleanliness, generosity, sobriety, and perseverance. Wolfram von Eschenbach in Parzifal, on the other hand, stresses a strong sense of right and wrong, compassion for the unfortunate, generosity, kindness, humility, mercy, courtesy (particularly to ladies), and cleanliness.

Geoffrey de Charney, the French hero from the Hundred Years’ War, also wrote a handbook on chivalry that is particularly valuable because he was a man with a powerful reputation as a chivalrous knight. (He was killed at the Battle of Poitiers defending the French battle standard, the oriflamme.) Charney puts the emphasis on love as a spur to great deeds and stresses that a knight must love “loyally” (with exclusive devotion to his one true love), but includes good manners, generosity, humility, fortitude, and courage among the qualities of chivalry as well. As a reflection of his career, Charney places greater value on fighting – stressing its hardships, deprivations, and risks – over frivolous tournaments.

William Marshal’s biographer, on the other hand, writing in the early 13th century, sees in tournaments a means of giving men a chance to demonstrate their “worth” – i.e., their courage, audacity, and skill at arms. These are the skills, combined with unwavering loyalty to his liege, that enable Marshal to rise from landless knight to regent of England. While Marshal (or at least his biographer) put the emphasis on courage, the themes of courtesy and discretion with respect to ladies, and generosity, are also present.

Readers interested in learning more about this fascinating concept can turn to:

Bibliography

Barber, Richard W. The Knight and Chivalry. The Boydell Press, 1970, 1974, 1995.

Duby, George. 1985. William Marshal: The Flower of Chivalry. Random House, 1985.

Hopkins, Andrea. Knights: The Complete Story of the Age of Chivalry, from Historical Fact to Tales of Romance and Poetry. Quarto Publishing, 1990.

and many other sources!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on June 15, 2018 03:00

June 7, 2018

Of Dowries, Dowers and Dowagers

Nothing is more indicative or determinative of women’s status in a society than their ability to hold and control property. Today, I look more closely at the sources of women's landed property in the Middle Ages: inheritance, dowries and dowers.

The first important fact is that in France, England, and the crusader states there were heiress (feminine), i.e. it was possible for women to inherit property and titles. This is not the case everywhere in the world even today. Second, heiresses were not dispossessed at marriage. Their husbands were expected to share in the control of their estates and the heiresses no longer controlled them exclusively, but they did not legally lose control or ownership.

Women might, of course, “bow to their husbands' wishes” for the sake of domestic harmony or be otherwise coerced or cajoled into granting their husbands more control than was legally required, but stronger women knew how to keep their husbands in their place. Geoffrey d’Anjou never titled himself “King of England.” Eleanor of Aquitaine took the Aquitaine back when she divorced Louis VII. Queen Melisende checked-mated Fulk d'Anjou when he tried to sideline her. Joan, Countess of Kent, did not bestow the honor of Kent on any of her three husbands; she retained it and passed it to her sons. Kings of Jerusalem lost their title, at the death of their wife, if there was no adult heir (e.g. Guy de Lusignan). Heiresses, furthermore, were not found only in the aristocracy; peasant and merchant daughters also had the right to inherit their estates, provided they had no brothers. Indignation over the fact that boys inherited first should not blind us to the more important fact that because girls could inherit, some girls held very powerful positions indeed.

A dowry was not an inheritance. It was, however, property that a maiden took with her into her marriage. Anyone who has read Jane Austin’s books knows that young ladies generally had a greater or lesser “dowry” settled upon them and the size of that dowry greatly affected their value on the marriage market. A dowry, however, was never a girl’s property. It was property that her father/brother/guardian owned but agreed to transfer to a girl’s husband at her marriage. In the Middle Ages, dowries were usually land. Royal brides brought entire lordships into their marriage (e.g. the Vexin), but the lesser lords might bestow a manor or two on their daughters and the daughters of gentry might bring a mill or the like to their husbands. Even peasant girls might call a pasture or orchard their dowry. With time dowries were increasingly monetary, either a lump sum paid at the time of the marriage to the bridegroom or a fixed annual income paid by the bride’s guardian (or his estate) to the husband. The key thing to remember about dowries, however, is that they were not the property of the bride. They passed from a girl's guardian to her husband.

Dowers on the other hand were women’s property. In the early Middle Ages, dowers were inalienable land bestowed on a wife at the time of her marriage. A woman owned and controlled her dower property, and she retained complete control of this property not only after her husband’s death, but even if her husband were to fall foul of the king, be attained for treason, and forfeit his own land and titles.

In the early Middle Ages, dowers were usually negotiated in advance of a marriage. Generally the father of the bride and the father of the groom would negotiate both the size and nature of the dowry and the dower at the same time. In short, the father of the bride would agree to transfer certain properties or a combination of properties and money to the groom at the marriage, and in exchange the father of the groom would designate properties as the new bride’s dower. These could, obviously, be identical. I.e. the father of the bride might agree to transfer certain properties to the bridegroom on the condition that they were designated his daughter’s dower, i.e. they were effectively transferred not to the control of the groom but to the bride after her marriage. Formally, however, the groom bestowed the “dower” on his wife at the church door immediately after marriage, and its size was variable.

In the absence of a formal agreement, however, English law came to recognize the right of every widow to one third of her late husband’s property. In this case, it fell to the husband’s lord (for barons, the crown) to determine exactly which pieces of property made up the dower portion after her husband’s death. Theoretically, the husband’s overlord was supposed to make this determination within forty days, but reality sometimes looked different. English judicial history is full of cases where tenacious widows litigated for decades to get their rights, an indication that justice was not always served rapidly, but also that women felt sufficiently protected by the law to take their case to court. The exception here was in the case of the widows of executed traitors. Whereas the older custom of designating the dower at the church door protected the widows of traitors, the idea that the dower was simply one third of a man’s estate at death meant that it was de-facto forfeited to the crown with the rest of a traitor’s lands, and his widow was left empty-handed.

This change in the nature of dowers may explain the increasing popularity of “jointures.” Jointures were not strictly women’s property as they were (as the name suggests) bestowed jointly on a couple at marriage. Nevertheless, the effect of jointures was to protect women financially. Property that was part of a jointure was controlled jointly so long as both partners lived, but became the sole property of the surviving partner at the death of the other. For men, that was nothing new, but for women it meant that in addition to the third of her husband’s estate that made up her dower portion, she had control of all her “jointure” lands. Furthermore, land held via “jointures” could not seized by the crown if either partner were convicted of treason; it remained the property of the survivor (usually the widow).

It was not uncommon in the High Middle Ages for women to successively marry two, three or even four husbands. After each marriage, the widow retained her dower and any jointures settled on her at the time of the marriage. Women who were politically well-connected, already wealthy and/or knew how to negotiate could therefore accumulate vast estates. “Dowagers” controlling these estates were not only wealthy and independent, they were influential and powerful -- at least within their family circles. They often controlled the income, marriages and dowries of their off-spring. One can imagine, they were not always popular but undoubtedly formidable!

It was not uncommon in the High Middle Ages for women to successively marry two, three or even four husbands. After each marriage, the widow retained her dower and any jointures settled on her at the time of the marriage. Women who were politically well-connected, already wealthy and/or knew how to negotiate could therefore accumulate vast estates. “Dowagers” controlling these estates were not only wealthy and independent, they were influential and powerful -- at least within their family circles. They often controlled the income, marriages and dowries of their off-spring. One can imagine, they were not always popular but undoubtedly formidable!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

The first important fact is that in France, England, and the crusader states there were heiress (feminine), i.e. it was possible for women to inherit property and titles. This is not the case everywhere in the world even today. Second, heiresses were not dispossessed at marriage. Their husbands were expected to share in the control of their estates and the heiresses no longer controlled them exclusively, but they did not legally lose control or ownership.

Women might, of course, “bow to their husbands' wishes” for the sake of domestic harmony or be otherwise coerced or cajoled into granting their husbands more control than was legally required, but stronger women knew how to keep their husbands in their place. Geoffrey d’Anjou never titled himself “King of England.” Eleanor of Aquitaine took the Aquitaine back when she divorced Louis VII. Queen Melisende checked-mated Fulk d'Anjou when he tried to sideline her. Joan, Countess of Kent, did not bestow the honor of Kent on any of her three husbands; she retained it and passed it to her sons. Kings of Jerusalem lost their title, at the death of their wife, if there was no adult heir (e.g. Guy de Lusignan). Heiresses, furthermore, were not found only in the aristocracy; peasant and merchant daughters also had the right to inherit their estates, provided they had no brothers. Indignation over the fact that boys inherited first should not blind us to the more important fact that because girls could inherit, some girls held very powerful positions indeed.

A dowry was not an inheritance. It was, however, property that a maiden took with her into her marriage. Anyone who has read Jane Austin’s books knows that young ladies generally had a greater or lesser “dowry” settled upon them and the size of that dowry greatly affected their value on the marriage market. A dowry, however, was never a girl’s property. It was property that her father/brother/guardian owned but agreed to transfer to a girl’s husband at her marriage. In the Middle Ages, dowries were usually land. Royal brides brought entire lordships into their marriage (e.g. the Vexin), but the lesser lords might bestow a manor or two on their daughters and the daughters of gentry might bring a mill or the like to their husbands. Even peasant girls might call a pasture or orchard their dowry. With time dowries were increasingly monetary, either a lump sum paid at the time of the marriage to the bridegroom or a fixed annual income paid by the bride’s guardian (or his estate) to the husband. The key thing to remember about dowries, however, is that they were not the property of the bride. They passed from a girl's guardian to her husband.

Dowers on the other hand were women’s property. In the early Middle Ages, dowers were inalienable land bestowed on a wife at the time of her marriage. A woman owned and controlled her dower property, and she retained complete control of this property not only after her husband’s death, but even if her husband were to fall foul of the king, be attained for treason, and forfeit his own land and titles.

In the early Middle Ages, dowers were usually negotiated in advance of a marriage. Generally the father of the bride and the father of the groom would negotiate both the size and nature of the dowry and the dower at the same time. In short, the father of the bride would agree to transfer certain properties or a combination of properties and money to the groom at the marriage, and in exchange the father of the groom would designate properties as the new bride’s dower. These could, obviously, be identical. I.e. the father of the bride might agree to transfer certain properties to the bridegroom on the condition that they were designated his daughter’s dower, i.e. they were effectively transferred not to the control of the groom but to the bride after her marriage. Formally, however, the groom bestowed the “dower” on his wife at the church door immediately after marriage, and its size was variable.

In the absence of a formal agreement, however, English law came to recognize the right of every widow to one third of her late husband’s property. In this case, it fell to the husband’s lord (for barons, the crown) to determine exactly which pieces of property made up the dower portion after her husband’s death. Theoretically, the husband’s overlord was supposed to make this determination within forty days, but reality sometimes looked different. English judicial history is full of cases where tenacious widows litigated for decades to get their rights, an indication that justice was not always served rapidly, but also that women felt sufficiently protected by the law to take their case to court. The exception here was in the case of the widows of executed traitors. Whereas the older custom of designating the dower at the church door protected the widows of traitors, the idea that the dower was simply one third of a man’s estate at death meant that it was de-facto forfeited to the crown with the rest of a traitor’s lands, and his widow was left empty-handed.

This change in the nature of dowers may explain the increasing popularity of “jointures.” Jointures were not strictly women’s property as they were (as the name suggests) bestowed jointly on a couple at marriage. Nevertheless, the effect of jointures was to protect women financially. Property that was part of a jointure was controlled jointly so long as both partners lived, but became the sole property of the surviving partner at the death of the other. For men, that was nothing new, but for women it meant that in addition to the third of her husband’s estate that made up her dower portion, she had control of all her “jointure” lands. Furthermore, land held via “jointures” could not seized by the crown if either partner were convicted of treason; it remained the property of the survivor (usually the widow).

It was not uncommon in the High Middle Ages for women to successively marry two, three or even four husbands. After each marriage, the widow retained her dower and any jointures settled on her at the time of the marriage. Women who were politically well-connected, already wealthy and/or knew how to negotiate could therefore accumulate vast estates. “Dowagers” controlling these estates were not only wealthy and independent, they were influential and powerful -- at least within their family circles. They often controlled the income, marriages and dowries of their off-spring. One can imagine, they were not always popular but undoubtedly formidable!

It was not uncommon in the High Middle Ages for women to successively marry two, three or even four husbands. After each marriage, the widow retained her dower and any jointures settled on her at the time of the marriage. Women who were politically well-connected, already wealthy and/or knew how to negotiate could therefore accumulate vast estates. “Dowagers” controlling these estates were not only wealthy and independent, they were influential and powerful -- at least within their family circles. They often controlled the income, marriages and dowries of their off-spring. One can imagine, they were not always popular but undoubtedly formidable!For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on June 07, 2018 21:58

May 30, 2018

The Seven Deadly Sins – And What They Say About Medieval Society

Dominated by the unified and omnipresent Catholic church, every man and woman in Medieval Europe knew about deadly (also cardinal) sins. These sins, according to Catholic theology, are behavior or feelings that are dangerous because they often lead humans to commit a mortal sin, the latter being an act that, unless repented and absolved, can lead to "spiritual death." A look at the seven sins recognized in the middle ages as "deadly" tells us a great deal about the emotions and behavior that medieval man considered morally reprehensible.

The seven deadly sins were: envy, gluttony, greed, lust, pride, sloth and wrath. Obviously some of these sins still strike us as anti-social behavior. Wrath, for example, is something no one would recommend and most people would agree brings harm – usually not only to the intended target. Likewise, no matter how tolerant modern society may be of sexual freedom for consenting adults, lust remains a dangerous emotional force behind many modern crimes from child abuse and rape to trafficking in persons. Finally, envy is still seen as undesirable.

Yet greed has more recently been praised as “good” – some people in modern society equating it with ambition and the driving force behind capitalism and free private enterprise. Even more striking, “pride” is something we hold up as a virtue, not a sin. We are proud of our country, proud of our armed forces, proud to be who we are – or at least we strive to be. And who nowadays would put “gluttony” or “sloth” right up there beside lust, wrath and envy?

Yet it is precisely these deadly sins that tell us the most about what the types of behavior Medieval Society particularly feared.

Yet it is precisely these deadly sins that tell us the most about what the types of behavior Medieval Society particularly feared.

In a society where hunger was never far from the poor and famines occurred regularly enough to scar the psyche of contemporaries, excessive consumption of food was not about getting fat it was about denying others. Because there were always poor who did not have enough to eat just around the corner, someone who indulged in gluttony rather than sharing excess food was violating the most fundamental of Christian principles. Nothing could be more essential to the concept of Christian charity than giving food to the hungry. Therefore person who not only kept what he/she needed for himself but engaged in excess eating was especially sinful. Greed was seen in the same light -- as taking more than one's "fair share" of finite resources.

Sloth is the other side of the same coin. In a society without machines, automation or robots, the production of all food, shelter and clothing depended on manual labor. Labor was the basis of survival, and survival was often endangered. Medieval society could not afford for any member to be idle. Even the rich were not idle. Medieval queens, countesses and ladies no less than their maids spun, wove and did other needlework – when they weren’t running their estates and kingdoms. The great magnates of the realm were the equivalent of modern corporate executives, managing vast estates and ensuring both production and distribution of food-stuffs. The gentry provided not just farm management but the services now provided by police, lawyers and court officials. In medieval society every man and woman had their place – and their job. Whether the job was to work the land or to pray for the dead, it was a job that the individual was expected to fulfill diligently and energetically. Sloth was a dangerous threat to a well-functioning society.

As for pride, the issue here was the fundamental medieval belief in God's Will. The prevalent belief of the Middle Ages was that each man was born into a specific place in society by the Will of God. It followed that just as no man had the right to be ashamed of his station in life, since that amounted to doubting God's wisdom in putting him there, he should not be proud of his wealth or status either because God had put him there and he should be thankful not proud. In other words, the greater one's status, wealth and success, the more humble one ought to be for God's Grace. Thus while other sins violated the Christian ideal of relations between men, pride violated the proper relationship between man and God. As such, it was the most egregious of all the deadly sins, and often leads the list in medieval texts.

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

The seven deadly sins were: envy, gluttony, greed, lust, pride, sloth and wrath. Obviously some of these sins still strike us as anti-social behavior. Wrath, for example, is something no one would recommend and most people would agree brings harm – usually not only to the intended target. Likewise, no matter how tolerant modern society may be of sexual freedom for consenting adults, lust remains a dangerous emotional force behind many modern crimes from child abuse and rape to trafficking in persons. Finally, envy is still seen as undesirable.

Yet greed has more recently been praised as “good” – some people in modern society equating it with ambition and the driving force behind capitalism and free private enterprise. Even more striking, “pride” is something we hold up as a virtue, not a sin. We are proud of our country, proud of our armed forces, proud to be who we are – or at least we strive to be. And who nowadays would put “gluttony” or “sloth” right up there beside lust, wrath and envy?

Yet it is precisely these deadly sins that tell us the most about what the types of behavior Medieval Society particularly feared.

Yet it is precisely these deadly sins that tell us the most about what the types of behavior Medieval Society particularly feared. In a society where hunger was never far from the poor and famines occurred regularly enough to scar the psyche of contemporaries, excessive consumption of food was not about getting fat it was about denying others. Because there were always poor who did not have enough to eat just around the corner, someone who indulged in gluttony rather than sharing excess food was violating the most fundamental of Christian principles. Nothing could be more essential to the concept of Christian charity than giving food to the hungry. Therefore person who not only kept what he/she needed for himself but engaged in excess eating was especially sinful. Greed was seen in the same light -- as taking more than one's "fair share" of finite resources.

Sloth is the other side of the same coin. In a society without machines, automation or robots, the production of all food, shelter and clothing depended on manual labor. Labor was the basis of survival, and survival was often endangered. Medieval society could not afford for any member to be idle. Even the rich were not idle. Medieval queens, countesses and ladies no less than their maids spun, wove and did other needlework – when they weren’t running their estates and kingdoms. The great magnates of the realm were the equivalent of modern corporate executives, managing vast estates and ensuring both production and distribution of food-stuffs. The gentry provided not just farm management but the services now provided by police, lawyers and court officials. In medieval society every man and woman had their place – and their job. Whether the job was to work the land or to pray for the dead, it was a job that the individual was expected to fulfill diligently and energetically. Sloth was a dangerous threat to a well-functioning society.

As for pride, the issue here was the fundamental medieval belief in God's Will. The prevalent belief of the Middle Ages was that each man was born into a specific place in society by the Will of God. It followed that just as no man had the right to be ashamed of his station in life, since that amounted to doubting God's wisdom in putting him there, he should not be proud of his wealth or status either because God had put him there and he should be thankful not proud. In other words, the greater one's status, wealth and success, the more humble one ought to be for God's Grace. Thus while other sins violated the Christian ideal of relations between men, pride violated the proper relationship between man and God. As such, it was the most egregious of all the deadly sins, and often leads the list in medieval texts.

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on May 30, 2018 22:32

May 25, 2018

Physical Factors: Heat

For the final entry in my five-part series looking at how objective factors can cause havoc for an unwary writer of historical fiction, I look at heat. The problem, as I noted at the beginning, is that even these measurable and seemingly immutable physical factors impacted people differently in the past.

Americans are notorious for their dependence on air conditioning. Many Europeans laugh at the way Americans cool their shops, offices and houses to temperatures below what they heat these places to in winter. Americans cannot even drive a short distance in the heat without turning on the air conditioning in their cars. We have, as a result, largely lost an understanding of how people cope with heat in the absence of artificial cooling systems run by electric motors.

Yet air conditioning was not widespread until the middle of the last century. For writers of historical fiction it is mostly irrelevant. People of the past who resided in regions where high temperatures could be expected for extended periods of time coped with heat primarily by designing homes for ventilation and/or shade. The architecture of the Middle East, for example, distinguished itself from "Western" (meaning northwestern European) architecture primarily by being inward facing. Exterior walls lacked windows, so that the oppressive heat of the sun did not find its way into the interior of homes or workplaces. Light came from central courtyards, which could mitigate the effect of the sun with shady trees and fountains or running water. Even markets were shaded. Whereas markets in the West were usually held in the open air -- in a 'market place,' a piazza, Platz or plateia, in places where the climate was more oven-like, markets were not only covered but windowless. The souks of the Middle East are long, interconnected, artificial tunnels, with only rare openings to the heavens.

Even markets were shaded. Whereas markets in the West were usually held in the open air -- in a 'market place,' a piazza, Platz or plateia, in places where the climate was more oven-like, markets were not only covered but windowless. The souks of the Middle East are long, interconnected, artificial tunnels, with only rare openings to the heavens.

Yet there were other architectural devices for coping with heat too. Southern France, Spain, and immigrants from the West to the Middle East adapted to the climate not by imitating the architecture of the Arabs (which had cultural as well as climatic roots), but by seeking to increase cross-ventilation. Instead of keeping windows to a minimum, they multiplied the number and size of them. Galleries, loges, and balconies enabled breezes to enter the shaded interior rooms. Rooms with windows or doorways facing different directions had air circulation, the same effect that fans had in later centuries. Additional cooling was effected with running water, i.e. public and private fountains, and with shade-giving trees, and hand fans.

Clothing too was affected by climate. As any history of costume will point out, people living in cold climates tended to wear fitted clothing, while people in warm climates prefer loose, draped clothing. In cold climates, people wore multiple layers of clothes from long fitted underwear, to looser hose and undershirts, various forms of over-garments such as aketons and gambesons, tunics and surcoats, on to vests, frocks, jackets, coats, cloaks, and capes. Women wore not just stockings and layers of petticoats, but corsets and slips and chemises under dresses, and shawls and capes and cloaks over them. With comparatively wind- and water-proof leather, wool and fur the effectiveness of these various garments in protecting against cold could improve.

But dressing for high temperatures was more difficult because there were often moral objections to absolute nakedness -- at least for women -- and the practical problem that too much exposure to the sun is harmful. The solution from Ancient Greece to the modern Bedouins was to develop clothing that created its own shade, while allowing the air to move around the body, thereby cooling and drying sweat.

The greatest difficulties in coping with heat in the past were encountered when people used to cool climates were confronted either with abnormal heat-waves in their own place of residence or traveled to a hot climate. One needs only think of difficulties English colonial officials and (even more so their wives!) encountered when trying to set up an English lifestyle in the hot and humid climate of Bombay or on the Potomac! But when settling or traveling for extended periods it was possible to adapt lighter fabrics and various tricks known to the natives.

Greater discomfort was created when unusually warm weather descended upon people in regions where it was uncommon. A heat wave in regions where homes and clothes were designed primarily for warding off the cold would have been intensely unpleasant. It was not possible for an Elizabethan or a Victorian lady to simply strip down to a tank top and shorts and walk around half-naked as women do today. Thus, dressed for the cold, they had to endure the heat without the benefit of easy bathing or deodorants. Yet, as I noted before, they may have had other ways of coping which we have long since forgotten.

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Americans are notorious for their dependence on air conditioning. Many Europeans laugh at the way Americans cool their shops, offices and houses to temperatures below what they heat these places to in winter. Americans cannot even drive a short distance in the heat without turning on the air conditioning in their cars. We have, as a result, largely lost an understanding of how people cope with heat in the absence of artificial cooling systems run by electric motors.

Yet air conditioning was not widespread until the middle of the last century. For writers of historical fiction it is mostly irrelevant. People of the past who resided in regions where high temperatures could be expected for extended periods of time coped with heat primarily by designing homes for ventilation and/or shade. The architecture of the Middle East, for example, distinguished itself from "Western" (meaning northwestern European) architecture primarily by being inward facing. Exterior walls lacked windows, so that the oppressive heat of the sun did not find its way into the interior of homes or workplaces. Light came from central courtyards, which could mitigate the effect of the sun with shady trees and fountains or running water.

Even markets were shaded. Whereas markets in the West were usually held in the open air -- in a 'market place,' a piazza, Platz or plateia, in places where the climate was more oven-like, markets were not only covered but windowless. The souks of the Middle East are long, interconnected, artificial tunnels, with only rare openings to the heavens.

Even markets were shaded. Whereas markets in the West were usually held in the open air -- in a 'market place,' a piazza, Platz or plateia, in places where the climate was more oven-like, markets were not only covered but windowless. The souks of the Middle East are long, interconnected, artificial tunnels, with only rare openings to the heavens.Yet there were other architectural devices for coping with heat too. Southern France, Spain, and immigrants from the West to the Middle East adapted to the climate not by imitating the architecture of the Arabs (which had cultural as well as climatic roots), but by seeking to increase cross-ventilation. Instead of keeping windows to a minimum, they multiplied the number and size of them. Galleries, loges, and balconies enabled breezes to enter the shaded interior rooms. Rooms with windows or doorways facing different directions had air circulation, the same effect that fans had in later centuries. Additional cooling was effected with running water, i.e. public and private fountains, and with shade-giving trees, and hand fans.

Clothing too was affected by climate. As any history of costume will point out, people living in cold climates tended to wear fitted clothing, while people in warm climates prefer loose, draped clothing. In cold climates, people wore multiple layers of clothes from long fitted underwear, to looser hose and undershirts, various forms of over-garments such as aketons and gambesons, tunics and surcoats, on to vests, frocks, jackets, coats, cloaks, and capes. Women wore not just stockings and layers of petticoats, but corsets and slips and chemises under dresses, and shawls and capes and cloaks over them. With comparatively wind- and water-proof leather, wool and fur the effectiveness of these various garments in protecting against cold could improve.

But dressing for high temperatures was more difficult because there were often moral objections to absolute nakedness -- at least for women -- and the practical problem that too much exposure to the sun is harmful. The solution from Ancient Greece to the modern Bedouins was to develop clothing that created its own shade, while allowing the air to move around the body, thereby cooling and drying sweat.

The greatest difficulties in coping with heat in the past were encountered when people used to cool climates were confronted either with abnormal heat-waves in their own place of residence or traveled to a hot climate. One needs only think of difficulties English colonial officials and (even more so their wives!) encountered when trying to set up an English lifestyle in the hot and humid climate of Bombay or on the Potomac! But when settling or traveling for extended periods it was possible to adapt lighter fabrics and various tricks known to the natives.

Greater discomfort was created when unusually warm weather descended upon people in regions where it was uncommon. A heat wave in regions where homes and clothes were designed primarily for warding off the cold would have been intensely unpleasant. It was not possible for an Elizabethan or a Victorian lady to simply strip down to a tank top and shorts and walk around half-naked as women do today. Thus, dressed for the cold, they had to endure the heat without the benefit of easy bathing or deodorants. Yet, as I noted before, they may have had other ways of coping which we have long since forgotten.

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on May 25, 2018 00:14

May 18, 2018

Physical Factors: Cold

Continuing with my five-part series looking at how objective factors can cause havoc for an unwary writer of historical fiction I look at cold. The problem, as I noted at the beginning, is that even these measurable and seemingly immutable physical factors impacted people differently in the past.

There is an old adage that there's no such thing as bad weather -- just the wrong clothes. The same could be said about housing. Eskimos have developed ways to deal with intense cold, enabling them to live in conditions the rest of us try to avoid. Furthermore, the exact same temperature can seem "chilly" to one person and "toasty" to another. Raised in Michigan and Maine but living many years in Africa, I always found it amusing when Africans would started wearing fur-trimmed parkas and gloves in weather I still found pleasant in a light jacket. When considering the impact of cold in the past, therefore, we need to consider not only the means of heating and dressing for cold, but also the fact that people may simply have been more "hardened" to cold than those of us pampered by central heating all our lives.

Another factor for novelists to consider when writing about cold in past centuries is that we have lost a great deal of knowledge. With the advent of central heating, we discarded bed-warmers and braziers, nightcaps and long-underwear. While we can rediscover some of these by reading accounts written in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, it is harder for novelists writing about more distant periods to fully understand just what devices people used to keep themselves warm.

It is, for example, still assumed and alleged that women wore no underpants in the Middle Ages simply because we have no images of women wearing this garment. But then again, why would we? Saints, queens and ladies, obviously, were not going to be shown in their underwear, while pornographic images tended to prefer women completely undressed. The fact that we know about men's underwear is because laborers often stripped down to their braies while working in the summer heat; women didn't do that. That doesn't mean they didn't wear underwear, and recent discoveries in Germany of braies with very pretty embroidery suggest that, indeed, many braies we assumed to be men's wear might have been worn by women instead or as well. In short, there is inevitably much we don't know about what people wore to keep warm.

Note the layers of clothing and hats worn even during a banquet.Similarly, because most of us encounter medieval life by visiting the ruins of castles, it is easy to forget that castles were not naked walls with the wind blowing through them. There were tapestries and wall hangings, carpets and rugs, and there were, if not glass windows, horn and parchment window coverings and shutters, sometimes inside and out. The equivalent of modern heating? Hardly, anything other than glass over the windows reduced the light, while anything short of double and triple glazing let in more cold than we are used to. Nevertheless, the temperatures in most castles were probably not as icy as you would think from reading many novels. If nothing else, most castles housed large numbers of people and they create their own heat!

Note the layers of clothing and hats worn even during a banquet.Similarly, because most of us encounter medieval life by visiting the ruins of castles, it is easy to forget that castles were not naked walls with the wind blowing through them. There were tapestries and wall hangings, carpets and rugs, and there were, if not glass windows, horn and parchment window coverings and shutters, sometimes inside and out. The equivalent of modern heating? Hardly, anything other than glass over the windows reduced the light, while anything short of double and triple glazing let in more cold than we are used to. Nevertheless, the temperatures in most castles were probably not as icy as you would think from reading many novels. If nothing else, most castles housed large numbers of people and they create their own heat!

Note the wall hangings and carpets.For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Note the wall hangings and carpets.For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

There is an old adage that there's no such thing as bad weather -- just the wrong clothes. The same could be said about housing. Eskimos have developed ways to deal with intense cold, enabling them to live in conditions the rest of us try to avoid. Furthermore, the exact same temperature can seem "chilly" to one person and "toasty" to another. Raised in Michigan and Maine but living many years in Africa, I always found it amusing when Africans would started wearing fur-trimmed parkas and gloves in weather I still found pleasant in a light jacket. When considering the impact of cold in the past, therefore, we need to consider not only the means of heating and dressing for cold, but also the fact that people may simply have been more "hardened" to cold than those of us pampered by central heating all our lives.

Another factor for novelists to consider when writing about cold in past centuries is that we have lost a great deal of knowledge. With the advent of central heating, we discarded bed-warmers and braziers, nightcaps and long-underwear. While we can rediscover some of these by reading accounts written in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, it is harder for novelists writing about more distant periods to fully understand just what devices people used to keep themselves warm.

It is, for example, still assumed and alleged that women wore no underpants in the Middle Ages simply because we have no images of women wearing this garment. But then again, why would we? Saints, queens and ladies, obviously, were not going to be shown in their underwear, while pornographic images tended to prefer women completely undressed. The fact that we know about men's underwear is because laborers often stripped down to their braies while working in the summer heat; women didn't do that. That doesn't mean they didn't wear underwear, and recent discoveries in Germany of braies with very pretty embroidery suggest that, indeed, many braies we assumed to be men's wear might have been worn by women instead or as well. In short, there is inevitably much we don't know about what people wore to keep warm.

Note the layers of clothing and hats worn even during a banquet.Similarly, because most of us encounter medieval life by visiting the ruins of castles, it is easy to forget that castles were not naked walls with the wind blowing through them. There were tapestries and wall hangings, carpets and rugs, and there were, if not glass windows, horn and parchment window coverings and shutters, sometimes inside and out. The equivalent of modern heating? Hardly, anything other than glass over the windows reduced the light, while anything short of double and triple glazing let in more cold than we are used to. Nevertheless, the temperatures in most castles were probably not as icy as you would think from reading many novels. If nothing else, most castles housed large numbers of people and they create their own heat!

Note the layers of clothing and hats worn even during a banquet.Similarly, because most of us encounter medieval life by visiting the ruins of castles, it is easy to forget that castles were not naked walls with the wind blowing through them. There were tapestries and wall hangings, carpets and rugs, and there were, if not glass windows, horn and parchment window coverings and shutters, sometimes inside and out. The equivalent of modern heating? Hardly, anything other than glass over the windows reduced the light, while anything short of double and triple glazing let in more cold than we are used to. Nevertheless, the temperatures in most castles were probably not as icy as you would think from reading many novels. If nothing else, most castles housed large numbers of people and they create their own heat! Note the wall hangings and carpets.For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Note the wall hangings and carpets.For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on May 18, 2018 21:56

May 10, 2018

Physical Factors: Darkness

Continuing with my five-part series looking at how objective factors can cause havoc for an unwary writer of historical fiction, I look at darkness. The problem, as I noted at the beginning of this series, is that even these measurable and seemingly immutable physical factors impacted people differently in the past.

Modern man is so surrounded by light that even when we seek the darkness it can be hard to find it. Cities have so many lights that they blot out the stars at night -- while revealing human concentration from outer space. Light is also available (most of the time) at the flip of a switch or the push of a button. It is readily available without noise, smell, sound or danger. This was not always the case.

What this means is that before the advent of electricity, light was much scarcer than it is today. For much of the past -- as is still the case in much of Africa today -- there was very little light after sunset at all. For the poor, activities requiring light -- repairing tools, needlework, reading -- could not be done after dark. Enter the story-teller and singers!

While there were some forms of lighting (to be discussed below) for lighting the interior of houses, workshops and taverns etc., there was no effective way to light up exterior spaces, except in densely populated cities. These, in periods of intensive urban life, possessed "street lighting" based on gas or oil lamps. What this meant is that travel beyond urban limits by night was greatly inhibited. Horses do not have headlights to help them find their way along the (often poorly maintained) roads. A lamp or torch had to be carried by a rider, which meant it did not light the surface of the (probably uneven, rocky or muddy) road on which the horse had to travel -- or by someone walking along beside or in front of the horse, which meant, of course, that the pace of travel was slowed to the pace of that man walking. Galloping across country in the dark of night is for Hollywood (which artificially darkens scenes filmed in broad daylight) not for the real world of the past. (I've tried to ride after dark by the way; it was a terrifying experience.)

Even inside, before the age of electricity, light was either natural light (from the sun) or it was produced by some sort of flame. Flame/fire, by its nature, brings a variety of risks with it. Fire/flames are hot and they can burn -- or set fire to other materials. Just as a reminder. A candle that simply falls -- or is knocked over -- can set an entire barn on fire, the straw easily igniting if dry. Hot wax burns. It can be a weapon. Things for a novelist to think about....

There were a variety of materials used to produce flame over time -- e.g. wood, reeds, wax, tallow, and different kinds of oil from blubber (whale fat) to olive oil. They have various properties, were more or less readily available depending on location, and more or less expensive. Tallow, for example, smokes and smells; bees wax, olive oil and blubber are comparatively clean flames -- and correspondingly more expensive. In short, a novelist needs to keep in mind a character's means and his/her ability to buy candles before describing their profuse use. Likewise, the number and kind of lighting can be used to hint at the economic status of a character.

Because candles are still in use today, we are generally familiar with the kinds of candle-holders that can be used. We are less familiar with candles marked with lines at intervals so that time could be measured by how far down they burned. Candelabra and chandeliers were also available to the wealthy in most past centuries, but the larger they were the more candles the consumed and so the more expensive they were to light. In most societies it was a sign of wealth to be able to burn chandeliers and candelabra. They were more likely to be used only on special occasions even by the rich.

Less common today, but very popular in ages past, particularly the ancient world, were oil lamps. These could be very cheap and simple pottery lamps, or more expensive and elegant lamps of bronze or glass. Below some examples from Roman times.

Note that two of these have handles so they could be carried around. As with torches and candles, the mobility of light was important because it was expensive and dangerous to leave flames, whatever their source, burning unattended. So rather than leaving lamps, lanterns, candles or torches burning everywhere, they were lit where people were collected and taken with people when they moved.

While candle and oil light, not to mention flames from a fireplace are less intense than modern electric lighting, it also has it's appeal. It is less harsh, less revealing, and less steady. It flickers and wavers. There are reasons why the classic "romantic dinner" is by candle-light. And anyone who has experienced the splendor of a candlelight mass will understand the spiritual strength of a candlelit cathedral or crypt.

(I know, not candle light, but lighting designed to imitate it.)For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

(I know, not candle light, but lighting designed to imitate it.)For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Modern man is so surrounded by light that even when we seek the darkness it can be hard to find it. Cities have so many lights that they blot out the stars at night -- while revealing human concentration from outer space. Light is also available (most of the time) at the flip of a switch or the push of a button. It is readily available without noise, smell, sound or danger. This was not always the case.

What this means is that before the advent of electricity, light was much scarcer than it is today. For much of the past -- as is still the case in much of Africa today -- there was very little light after sunset at all. For the poor, activities requiring light -- repairing tools, needlework, reading -- could not be done after dark. Enter the story-teller and singers!

While there were some forms of lighting (to be discussed below) for lighting the interior of houses, workshops and taverns etc., there was no effective way to light up exterior spaces, except in densely populated cities. These, in periods of intensive urban life, possessed "street lighting" based on gas or oil lamps. What this meant is that travel beyond urban limits by night was greatly inhibited. Horses do not have headlights to help them find their way along the (often poorly maintained) roads. A lamp or torch had to be carried by a rider, which meant it did not light the surface of the (probably uneven, rocky or muddy) road on which the horse had to travel -- or by someone walking along beside or in front of the horse, which meant, of course, that the pace of travel was slowed to the pace of that man walking. Galloping across country in the dark of night is for Hollywood (which artificially darkens scenes filmed in broad daylight) not for the real world of the past. (I've tried to ride after dark by the way; it was a terrifying experience.)

Even inside, before the age of electricity, light was either natural light (from the sun) or it was produced by some sort of flame. Flame/fire, by its nature, brings a variety of risks with it. Fire/flames are hot and they can burn -- or set fire to other materials. Just as a reminder. A candle that simply falls -- or is knocked over -- can set an entire barn on fire, the straw easily igniting if dry. Hot wax burns. It can be a weapon. Things for a novelist to think about....

There were a variety of materials used to produce flame over time -- e.g. wood, reeds, wax, tallow, and different kinds of oil from blubber (whale fat) to olive oil. They have various properties, were more or less readily available depending on location, and more or less expensive. Tallow, for example, smokes and smells; bees wax, olive oil and blubber are comparatively clean flames -- and correspondingly more expensive. In short, a novelist needs to keep in mind a character's means and his/her ability to buy candles before describing their profuse use. Likewise, the number and kind of lighting can be used to hint at the economic status of a character.

Because candles are still in use today, we are generally familiar with the kinds of candle-holders that can be used. We are less familiar with candles marked with lines at intervals so that time could be measured by how far down they burned. Candelabra and chandeliers were also available to the wealthy in most past centuries, but the larger they were the more candles the consumed and so the more expensive they were to light. In most societies it was a sign of wealth to be able to burn chandeliers and candelabra. They were more likely to be used only on special occasions even by the rich.