Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 38

November 25, 2017

Kolossi - Settings for the "Last Crusader Kingdom"

Richard the Lionheart's first rout of Isaac Comnenus allegedly took place at Kolossi. Later it was the site of a Hospitaller Commandery and a magnificent example of crusader architecture of the 15th century has survived to this day. Although this castle did not yet exist at the time in which The Last Crusader Kingdom is set, we know that the current structure was built on foundations of earlier buildings and this inspired an important episode in the novel. Below is a brief history of Kolossi.

Kolossi is located just 10 kilometers (6 miles) west of Limassol on a fertile coastal plain. In 1191, according to the chronicles, Isaac Comnenus collected his army here, and Richard the Lionheart surprised the camp at dawn, over-running the tents and capturing a huge treasure in equipment and furnishing, while Isaac Comnenus just barely managed to escape on a swift steed. All sources agree that at this time there was no fortress on the site.

Kolossi is located just 10 kilometers (6 miles) west of Limassol on a fertile coastal plain. In 1191, according to the chronicles, Isaac Comnenus collected his army here, and Richard the Lionheart surprised the camp at dawn, over-running the tents and capturing a huge treasure in equipment and furnishing, while Isaac Comnenus just barely managed to escape on a swift steed. All sources agree that at this time there was no fortress on the site.

In 1210, however, the estate of Kolossi which included some 60 villages, was turned over to the Knights Hospitaller by King Hugh I. The original castle is believed to date from this period. Ruins of this castle have been found and exposed by archaeologists:

The land was fertile and the Hospitaller set about cultivating products for export: wheat, cotton, sugar, oil and wine. Indeed, the wine produced here became famous as "Commandaria" -- a sweet, red wine allegedly preferred by the Plantagenet kings of England.

Sugar production and export, however, was also a highly lucrative business, and the remains of a 13th century sugar factory are located directly beside the castle. These are erected on the remains of a 12th century factory.

Sugar production and export, however, was also a highly lucrative business, and the remains of a 13th century sugar factory are located directly beside the castle. These are erected on the remains of a 12th century factory.

Sugar production and refining requires large quantities of water and the remains of the sophisticated aqueducts and drains have also been found at Kolossi.

It was this factory that inspired me to use Kolossi as the venue of an important incident in The Last Crusader Kingdom -- an attack by the rebels against the economic infrastructure of the island.

Historically, the Hospitallers moved their headquarters to Cyprus (possibly Kolossi) after the fall of Acre in 1291, but mindful of the greed and jealousy of princes, the Hospitallers wisely acquired the island of Rhodes and moved the bulk of their resources there early in the 14th century. Nevertheless, Kolossi remained an important source of income, and the castle was last refurbished in the 15th century. This last building is what we can see today. Below are a number of pictures which I took during my most recent visit in 2012.

Left the "Donjon" from the innerward.

Right one of the ground floor chambers presumably used for storage.

The interior stairs from the cellars to the first floor.

The interior stairs from the cellars to the first floor.

One of the spacious upper chambers.

A fireplace:

Kolossi is located just 10 kilometers (6 miles) west of Limassol on a fertile coastal plain. In 1191, according to the chronicles, Isaac Comnenus collected his army here, and Richard the Lionheart surprised the camp at dawn, over-running the tents and capturing a huge treasure in equipment and furnishing, while Isaac Comnenus just barely managed to escape on a swift steed. All sources agree that at this time there was no fortress on the site.

Kolossi is located just 10 kilometers (6 miles) west of Limassol on a fertile coastal plain. In 1191, according to the chronicles, Isaac Comnenus collected his army here, and Richard the Lionheart surprised the camp at dawn, over-running the tents and capturing a huge treasure in equipment and furnishing, while Isaac Comnenus just barely managed to escape on a swift steed. All sources agree that at this time there was no fortress on the site.In 1210, however, the estate of Kolossi which included some 60 villages, was turned over to the Knights Hospitaller by King Hugh I. The original castle is believed to date from this period. Ruins of this castle have been found and exposed by archaeologists:

The land was fertile and the Hospitaller set about cultivating products for export: wheat, cotton, sugar, oil and wine. Indeed, the wine produced here became famous as "Commandaria" -- a sweet, red wine allegedly preferred by the Plantagenet kings of England.

Sugar production and export, however, was also a highly lucrative business, and the remains of a 13th century sugar factory are located directly beside the castle. These are erected on the remains of a 12th century factory.

Sugar production and export, however, was also a highly lucrative business, and the remains of a 13th century sugar factory are located directly beside the castle. These are erected on the remains of a 12th century factory. Sugar production and refining requires large quantities of water and the remains of the sophisticated aqueducts and drains have also been found at Kolossi.

It was this factory that inspired me to use Kolossi as the venue of an important incident in The Last Crusader Kingdom -- an attack by the rebels against the economic infrastructure of the island.

Historically, the Hospitallers moved their headquarters to Cyprus (possibly Kolossi) after the fall of Acre in 1291, but mindful of the greed and jealousy of princes, the Hospitallers wisely acquired the island of Rhodes and moved the bulk of their resources there early in the 14th century. Nevertheless, Kolossi remained an important source of income, and the castle was last refurbished in the 15th century. This last building is what we can see today. Below are a number of pictures which I took during my most recent visit in 2012.

Left the "Donjon" from the innerward.

Right one of the ground floor chambers presumably used for storage.

The interior stairs from the cellars to the first floor.

The interior stairs from the cellars to the first floor.

One of the spacious upper chambers.

A fireplace:

Published on November 25, 2017 01:27

November 17, 2017

CHANTICLEER REVIEW of "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

WINNER OF A B.R.A.G. MEDALLION!

The Last Crusader Kingdom: Dawn of a Dynasty in Twelfth-Century Cyprus

Chanticleer Review

In the Introduction and Acknowledgements section of her fascinating novel, The Last Crusader Kingdom: Dawn of a Dynasty in Twelfth-Century Cyprus, Helena P. Schrader notes that ". . . the historical basis for this novel is very thin," and that the book serves as "a fictional depiction of events as I believe they could have happened." Upon finishing the book, one concludes that only the rare reader would disagree with Schrader's version of the historical events that comprise her narrative. Her comprehensive research and impressive scholarship are evident on every single page. This is a work of historical fiction, admittedly, but Schrader clearly was tireless in exhuming every possible detail to piece together as authentic a history of medieval Cyprus, 1193-1198, as possible.

The establishment of a Latin Kingdom on the formerly Byzantine island of Cyprus in the late twelfth-century is as engrossing and intricate a chapter in history as possible, one that involved a plethora of cultures, religions, family dynasties, battles, treaties, and, inevitably, human greed and vanity. Schrader addresses both public and private lives and demonstrates how their intertwining shaped history. She considers all classes of society, from barons to beggars. It would be easy to get lost amongst the riveting and numerous details, but the author takes the reader by the hand and offers a guided tour to people, places, and events. The novel includes a Cast of Characters, Genealogical Charts for the Houses of Jerusalem, Lusignan, and Ibelin, as well as historical maps of Cyprus and the Outremer. Her Historical Notes underscore the depth of her research, and she also provides a glossary to orient the reader with historical and regional terms.

Schrader matches her exhaustive research with a thoroughly captivating narrative. Her prose shimmers with elegant confidence and wit. The story traces how this strategically positioned island, formerly fraught with the greatest animosity between the inept and despised Frankish ruler, Guy de Lusignan, and the Greek Orthodox natives is pacified even after the influx of Latin immigrants. How all this came about is as exciting and adventurous tale as anyone could imagine. Schrader pays keen attention to how power is grasped, nourished, and maintained, and her tale demonstrates the essential and timeless balance of politics, religion, economy, and public relations. Although the novel takes place in medieval times, much of it could serve as a primer for twenty-first-century global politics and diplomacy.

One might expect the medieval world to be dominated by men, yet the author fully addresses the lives of women. Obviously siring male heirs was of importance in the twelfth century, but Schrader does not limit episodes involving female characters to pregnancy and birth. She emphasizes their role as astute advisers to their husbands and other male relations. The women understood that marriages were opportunities for strategic alliances and personal power. Queens and wives of public figures were keenly aware of the critical public relations roles they played in binding their subjects to the ruling families.

The reader also learns a wealth of information on shipbuilding, irrigation, aqueducts, woodcarving, piracy, on and on. The Last Crusader Kingdom is not just the story of key families ascending to power; it's also an enlightening overview on the state of technology, the arts, and crime at the close of the twelfth century. The reader trusts Schrader's depiction of events as accurate in large part because her meticulous research makes every scene vivid and memorable. Schrader matches her exhaustive historical research with a thoroughly captivating narrative.

Helena P. Schrader is an author who doesn't just bring history to life but one who reminds us that each passing moment is also history. To understand the events reported on the front pages of today's newspapers, there's no greater teacher than the past. The Last Crusader Kingdomis filled with lessons we'd be foolish to neglect. -- CHANTICLEER REVIEWS

Buy Now

Buy Now

Published on November 17, 2017 21:03

November 12, 2017

"Negotiations with the Devil" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

The German philosopher Carl von Clausewitz rightly noted that war is the continuation of politics by "other" means. Likewise, when the political objectives of a conflict remain illusive -- or the price of conflict becomes too high -- most parties seek to resolve differences by non-violent means. At that point negotiations with "the enemy" -- whoever that may be -- become necessary, and compromise essential.

From the top of the escarpment, Sir Galvin and Ibelin’s other men watched anxiously. They shared Ibelin’s assessment of the sailors, and while they could not see Brother Zotikos’ eyes, they hardly needed to. His every gesture exuded hostility and aggression, so much so that [the dog] Barry lowered his head and curled his lips in a threatening stance. Sir Galvin glanced over his shoulder to Sir Sergios. The Maronite Syrian had served the Count of Tripoli at Hattin, but had been fighting under Ibelin’s banner ever since the great armed pilgrimage from the West that had wrested control of the coast back from Saladin. He was a superb archer, and he already had his bow out of its case. His quiver hung from the pommel of his saddle.

Sir Galvin nodded to him, and he fitted an arrow onto the string, lifted the bow, pulled the string back to his ear, and looked down the arrow with narrowed eyes at his target: the Greek monk’s broad chest. He nodded, then gently eased the string back to the uncocked position, yet kept the arrow notched. At this range, he was confident he could kill the Greek monk before he could do any harm to their lord.

None of Ibelin’s men could hear what was being said, but they could see the monk gesturing wildly with his arms. He threw them out wide, then rotated his right arm like a windmill. Then his hands formed fists that he held under Ibelin’s nose. A moment later he thrust out an index finger and jabbed the air in front of Ibelin’s face―eliciting an angry warning bark from Barry, whom John was visibly restraining from attacking.

Throughout it all, Ibelin appeared impassive. His stance was relaxed, his arms akimbo, his weight on his right leg with his left bent and slightly forward. His men recognized he was actually poised to swing his weight forward with his right fist if he needed to. Compared to the apparent flood of words that accompanied the dramatic gestures of the monk, Ibelin appeared to say very little. Once or twice he lifted his head as if to make a short remark. Each time his words provoked a new round of angry gestures from the monk, followed by increasingly violent gestures from Barry.

Once Father Andronikos tried to intervene, only to harvest a series of stabs with an index finger in his direction from the younger monk. John, meanwhile, was having trouble holding his dog, and was clearly distressed, confused, and a little frightened. He looked at his father for guidance, but the elder Ibelin remained calm, signaling for him to restrain the dog.

“I don’t think things are going well,” Sir Galvin observed generally, and Georgios shook his head sadly.

Abruptly, Ibelin turned his back on the monk and started back up the escarpment. The monk shouted furiously after him, making Georgios wince at the crude threat. Sir Galvin looked over, on the brink of asking for a translation, but then thought better of it. On the beach Father Andronikos was evidently trying to reason with the angry young monk, his hand on the latter’s arm. The younger man shook him off, and with a violent, dismissive gesture started striding toward his boat. The sailors were already shoving it back into the water; the stern floated while the bow remained on the sand, ready for Zotikos to re-board.

Ibelin reached the top of the escarpment slightly breathless from the climb, and held out his hand for his sword belt. “Hopeless!” he announced to his men, snatching the belt and wrapping it around his waist to buckle it snugly. “He insists that they will keep fighting until we are either driven from the island like the Templars, or all dead.” He grabbed the reins of his stallion, threw them back over the horse’s head, and gathered them up as he pointed his toe in the stirrup to haul himself into the saddle.

He was so agitated that he swung his horse around and started to ride off before John had had a chance to mount. Then he caught himself and waited, his expression grim.

“So they wouldn’t consider exchanging the abbot for Toron?” Sir Galvin asked, puzzled and disbelieving.

“No. That monk is a fanatic. He is incapable of compromise or negotiation. Saladin was pure reason compared to him!”

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

From the top of the escarpment, Sir Galvin and Ibelin’s other men watched anxiously. They shared Ibelin’s assessment of the sailors, and while they could not see Brother Zotikos’ eyes, they hardly needed to. His every gesture exuded hostility and aggression, so much so that [the dog] Barry lowered his head and curled his lips in a threatening stance. Sir Galvin glanced over his shoulder to Sir Sergios. The Maronite Syrian had served the Count of Tripoli at Hattin, but had been fighting under Ibelin’s banner ever since the great armed pilgrimage from the West that had wrested control of the coast back from Saladin. He was a superb archer, and he already had his bow out of its case. His quiver hung from the pommel of his saddle.

Sir Galvin nodded to him, and he fitted an arrow onto the string, lifted the bow, pulled the string back to his ear, and looked down the arrow with narrowed eyes at his target: the Greek monk’s broad chest. He nodded, then gently eased the string back to the uncocked position, yet kept the arrow notched. At this range, he was confident he could kill the Greek monk before he could do any harm to their lord.

None of Ibelin’s men could hear what was being said, but they could see the monk gesturing wildly with his arms. He threw them out wide, then rotated his right arm like a windmill. Then his hands formed fists that he held under Ibelin’s nose. A moment later he thrust out an index finger and jabbed the air in front of Ibelin’s face―eliciting an angry warning bark from Barry, whom John was visibly restraining from attacking.

Throughout it all, Ibelin appeared impassive. His stance was relaxed, his arms akimbo, his weight on his right leg with his left bent and slightly forward. His men recognized he was actually poised to swing his weight forward with his right fist if he needed to. Compared to the apparent flood of words that accompanied the dramatic gestures of the monk, Ibelin appeared to say very little. Once or twice he lifted his head as if to make a short remark. Each time his words provoked a new round of angry gestures from the monk, followed by increasingly violent gestures from Barry.

Once Father Andronikos tried to intervene, only to harvest a series of stabs with an index finger in his direction from the younger monk. John, meanwhile, was having trouble holding his dog, and was clearly distressed, confused, and a little frightened. He looked at his father for guidance, but the elder Ibelin remained calm, signaling for him to restrain the dog.

“I don’t think things are going well,” Sir Galvin observed generally, and Georgios shook his head sadly.

Abruptly, Ibelin turned his back on the monk and started back up the escarpment. The monk shouted furiously after him, making Georgios wince at the crude threat. Sir Galvin looked over, on the brink of asking for a translation, but then thought better of it. On the beach Father Andronikos was evidently trying to reason with the angry young monk, his hand on the latter’s arm. The younger man shook him off, and with a violent, dismissive gesture started striding toward his boat. The sailors were already shoving it back into the water; the stern floated while the bow remained on the sand, ready for Zotikos to re-board.

Ibelin reached the top of the escarpment slightly breathless from the climb, and held out his hand for his sword belt. “Hopeless!” he announced to his men, snatching the belt and wrapping it around his waist to buckle it snugly. “He insists that they will keep fighting until we are either driven from the island like the Templars, or all dead.” He grabbed the reins of his stallion, threw them back over the horse’s head, and gathered them up as he pointed his toe in the stirrup to haul himself into the saddle.

He was so agitated that he swung his horse around and started to ride off before John had had a chance to mount. Then he caught himself and waited, his expression grim.

“So they wouldn’t consider exchanging the abbot for Toron?” Sir Galvin asked, puzzled and disbelieving.

“No. That monk is a fanatic. He is incapable of compromise or negotiation. Saladin was pure reason compared to him!”

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on November 12, 2017 01:00

November 4, 2017

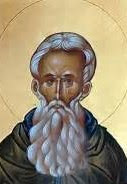

Characters in The Last Crusader Kingdom: Brother Zotikos & Father Andronikos

Continuing with my series on the fictional characters in the Last Crusader Kingdom, I want to turn to the two Greek clerics, who play a significant role in this novel:

Brother Zotikos and Father Andronikos.

Brother Zotikos is the very first character the reader encounters. He is a peaceful monk in an impoverished mountain monastery worried about a pregnant cow when the brutality of foreign occupation breaks in upon his peaceful world. The “Franks” are burning the village at the foot of the mountain and refugees flood into the monastery. It is a life-changing moment for Brother Zotikos; he cannot come to terms with the unjustified violence and he turns to rebellion.

I created this rebellious monk because we know that the greatest (not to say only) opposition to Frankish rule on Cyprus came from the Orthodox church. The Byzantine nobility, like the Frankish nobility in the centuries to come, had estates on the mainland. Many had already abandoned Cyprus during the reign of the despot Isaac Comnenus because of his rapacious policies. Others cut their losses when confronted with the Templar’s equally oppressive rule. The church was not so quick to abandon the island or its flock.

Of the nobles that did remain on the island, we are told that many did homage to Richard the Lionheart, and that others were rewarded with fiefs by the Lusignans for their loyalty. There is no recorded instance of a Greek knight or noble taking up arms against Frankish rule.

But there was resistance, armed resistance, resistance strong enough to drive the Templars from the island. The only specific rebel the chronicles tell us about is a monk, a relative of the despot Isaac Comnenus. It therefore seemed most appropriate to make the representative of Cypriot opposition to Frankish rule a monk.

Having made that decision, Zotikos took over. He was young, vigorous and he has been turned into a fanatic by an encounter with violent injustice. I thought it believable that he would be like any young fanatic fighting for a cause he believes is completely sacred ―whether it is Communism, liberation theology, or ISIS. This means that while at first he is justified, his own fanaticism eventually becomes his enemy and drags him down a course that no longer serves his own goals.

Father Andronikos is, if you like, the natural antidote to Brother Zotikos. He represents the church at its most positive: a source of inner strength and an advocate of peace. Father Andronikos as a mature man with a family cares more about resolution than revenge.

Father Andronikos also serves the important role of spokesman for the native population of Cyprus. Since all my principal characters are new-comers to the island, even Maria Comnena, it was important to have someone who could speak for the Cypriots. It would have been difficult to work in more about the history of Cyprus, what had happened before the arrival of Aimery and John, without a character of this nature.

Because Orthodox priests can and do marry and have families, Father Andronikos was also a means of introducing John to a decent Greek girl. As a young Frankish noble it would otherwise have been very difficult to develop a circumstance in which he might meet and interact with a Greek maiden.

Last but not least, he is a tribute to the Greek Orthodox priests I have encountered in my life.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Brother Zotikos and Father Andronikos.

Brother Zotikos is the very first character the reader encounters. He is a peaceful monk in an impoverished mountain monastery worried about a pregnant cow when the brutality of foreign occupation breaks in upon his peaceful world. The “Franks” are burning the village at the foot of the mountain and refugees flood into the monastery. It is a life-changing moment for Brother Zotikos; he cannot come to terms with the unjustified violence and he turns to rebellion.

I created this rebellious monk because we know that the greatest (not to say only) opposition to Frankish rule on Cyprus came from the Orthodox church. The Byzantine nobility, like the Frankish nobility in the centuries to come, had estates on the mainland. Many had already abandoned Cyprus during the reign of the despot Isaac Comnenus because of his rapacious policies. Others cut their losses when confronted with the Templar’s equally oppressive rule. The church was not so quick to abandon the island or its flock.

Of the nobles that did remain on the island, we are told that many did homage to Richard the Lionheart, and that others were rewarded with fiefs by the Lusignans for their loyalty. There is no recorded instance of a Greek knight or noble taking up arms against Frankish rule.

But there was resistance, armed resistance, resistance strong enough to drive the Templars from the island. The only specific rebel the chronicles tell us about is a monk, a relative of the despot Isaac Comnenus. It therefore seemed most appropriate to make the representative of Cypriot opposition to Frankish rule a monk.

Having made that decision, Zotikos took over. He was young, vigorous and he has been turned into a fanatic by an encounter with violent injustice. I thought it believable that he would be like any young fanatic fighting for a cause he believes is completely sacred ―whether it is Communism, liberation theology, or ISIS. This means that while at first he is justified, his own fanaticism eventually becomes his enemy and drags him down a course that no longer serves his own goals.

Father Andronikos is, if you like, the natural antidote to Brother Zotikos. He represents the church at its most positive: a source of inner strength and an advocate of peace. Father Andronikos as a mature man with a family cares more about resolution than revenge.

Father Andronikos also serves the important role of spokesman for the native population of Cyprus. Since all my principal characters are new-comers to the island, even Maria Comnena, it was important to have someone who could speak for the Cypriots. It would have been difficult to work in more about the history of Cyprus, what had happened before the arrival of Aimery and John, without a character of this nature.

Because Orthodox priests can and do marry and have families, Father Andronikos was also a means of introducing John to a decent Greek girl. As a young Frankish noble it would otherwise have been very difficult to develop a circumstance in which he might meet and interact with a Greek maiden.

Last but not least, he is a tribute to the Greek Orthodox priests I have encountered in my life.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on November 04, 2017 02:00

October 28, 2017

"I'll Make You a Queen" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

In this episode, Aimery's bid to become Lord of Cyprus is not going well. The insurgency appears to be gaining strength and his wife of roughly 20 years, Eschiva, has just miscarried his child.

Aimery sat crumpled in a chair with his face in his hands. Balian stood opposite him, and he interrupted himself at the sight of [his wife] Maria Zoe. As Balian's voice fell silent, Aimery sat bolt upright and twisted around to look at Maria Zoe, an anguished look on his ravaged face.

"She's fine, Aimery," Maria Zoe assured him, coming closer and laying her hand on his shoulder. "She's miscarried a child, but she's fine. The bleeding has stopped; the afterbirth has discharged cleanly; she has no fever.... Eschiva's problem is not physical, Aimery. It's emotional. She seems to think you will not forgive her for losing this child."

Aimery scowled. "Where does she come up with nonsense like--"

"That doesn't matter. The point is, she thinks you will blame her for this dead child, so much so that you will set her aside--"

"That's ridiculous! I--"

Maria Zoe held up her hands. "I'm only telling you so you know what to say to her when you go to her.... Come. Eschiva needs some rest, but she won't be able to sleep until she's been reassured you still love her and do not blame her."

Aimery nodded and then remembered to ask, "How do I look?"

"Terrible," Balian answered, "which is just the way you should look. She should see how distressed you have been."

Aimery nodded absently; in his mind he was already preparing his words. Maria Zoe led him through the corridors, and as he approached the chamber containing his wife, he was pleased by the way the women all went down on their knees and bowed their heads nearly to the floor -- until he realized it was for Maria Comnena, not himself. Damn it, he thought, but then he was inside a room gleaming with wet marble and smelling of roses. The sheets were so white they seemed to glow. There were even fresh hibiscus in a glass vase beside the bed. Eschiva was all but lost in the puffy pillows, and her huge eyes followed him as he approached the side of the bed. She reached out a hand to him tentatively; it appeared to plead more than welcome.

Aimery fell on his knees beside the bed, took her hand and kissed it, and then held it to his cheek. "Forgive me, Eschiva," he croaked out. "I should never have allowed you to risk your own life and that of our child by coming with me."

"Aimery, my love," Eschiva assured him, struggling to sit up more, and Beatrice at once came to help her. "Aimery, it's all right as long as you aren't angry," she told him.

"Why, my love, should I be angry with you? You have done nothing wrong. You risked your life and that of our child to support me, and any setbacks we have are my fault -- but believe me, Eschiva." Aimery's voice was getting stronger as he spoke, reassured by how serene, self-possessed, and loving Eschiva looked. "I swear to you, Eschiva," Aimery declared, "I will make you a queen. They will recognized you as their queen. And, so help me God, our children and our children's children will rule this island kingdom for the next three hundred years!"

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Aimery sat crumpled in a chair with his face in his hands. Balian stood opposite him, and he interrupted himself at the sight of [his wife] Maria Zoe. As Balian's voice fell silent, Aimery sat bolt upright and twisted around to look at Maria Zoe, an anguished look on his ravaged face.

"She's fine, Aimery," Maria Zoe assured him, coming closer and laying her hand on his shoulder. "She's miscarried a child, but she's fine. The bleeding has stopped; the afterbirth has discharged cleanly; she has no fever.... Eschiva's problem is not physical, Aimery. It's emotional. She seems to think you will not forgive her for losing this child."

Aimery scowled. "Where does she come up with nonsense like--"

"That doesn't matter. The point is, she thinks you will blame her for this dead child, so much so that you will set her aside--"

"That's ridiculous! I--"

Maria Zoe held up her hands. "I'm only telling you so you know what to say to her when you go to her.... Come. Eschiva needs some rest, but she won't be able to sleep until she's been reassured you still love her and do not blame her."

Aimery nodded and then remembered to ask, "How do I look?"

"Terrible," Balian answered, "which is just the way you should look. She should see how distressed you have been."

Aimery nodded absently; in his mind he was already preparing his words. Maria Zoe led him through the corridors, and as he approached the chamber containing his wife, he was pleased by the way the women all went down on their knees and bowed their heads nearly to the floor -- until he realized it was for Maria Comnena, not himself. Damn it, he thought, but then he was inside a room gleaming with wet marble and smelling of roses. The sheets were so white they seemed to glow. There were even fresh hibiscus in a glass vase beside the bed. Eschiva was all but lost in the puffy pillows, and her huge eyes followed him as he approached the side of the bed. She reached out a hand to him tentatively; it appeared to plead more than welcome.

Aimery fell on his knees beside the bed, took her hand and kissed it, and then held it to his cheek. "Forgive me, Eschiva," he croaked out. "I should never have allowed you to risk your own life and that of our child by coming with me."

"Aimery, my love," Eschiva assured him, struggling to sit up more, and Beatrice at once came to help her. "Aimery, it's all right as long as you aren't angry," she told him.

"Why, my love, should I be angry with you? You have done nothing wrong. You risked your life and that of our child to support me, and any setbacks we have are my fault -- but believe me, Eschiva." Aimery's voice was getting stronger as he spoke, reassured by how serene, self-possessed, and loving Eschiva looked. "I swear to you, Eschiva," Aimery declared, "I will make you a queen. They will recognized you as their queen. And, so help me God, our children and our children's children will rule this island kingdom for the next three hundred years!"

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on October 28, 2017 01:25

October 21, 2017

St. Hilarion - Settings for "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

In writing about Medieval Cyprus it is impossible to overlook the most powerful and dramatic of all the medieval fortresses: St. Hilarion. It is the setting of several key historical episodes that inherently fall within the framework of my novels -- and I couldn't resist using it for fictional episodes as well. Below is a brief history.

The castle stands 700 meters (2275 feet) above see level on the narrow ridge of the Kyrenia range just slightly southwest of the port of Kyrenia. It was built by the Byzantine governor of the island after the Comnenus emperors re-established full control over Cyprus in the late 10th. Constructed between 1102 and 1110, it was called Didymos by the Byzantines for the twin mountain peaks between which the upper castle sits. The crusaders, however, preferred to call it the castle of "Dieu d'Amour" (the God of Love) and the locals continued to refer to it as St. Hilarion because the saint of that name had built a monastery, been buried and venerated here long before the castle was built.

Remnants of the Castle Church

Remnants of the Castle Church

The castle boasts three lines of defense, and was never taken by assault. It was, however, frequently besieged.

View from the upper to the lower ward.

View from the upper to the lower ward.

In July/August 1228, after Emperor Friedrich II accused John d'Ibelin of malfeasance and attempted to seize his fief without trial, Ibelin secured control of St. Hilarion, had it well provisioned and moved his and his supporters' dependents there in preparation for a confrontation. Ibelin was persuaded to turn the castle over to the King of Cyprus in exchange for the release of his two hostage sons -- or vice versa, depending on how one interprets the negotiations.

When Friedrich II left the Holy Land for the West, he turned St. Hilarion over to his appointed baillies with orders for them to prevent the Ibelins from setting foot on the island. Within two months, however, the Ibelins had pulled together a sufficient army to challenge this (illegal) order head on. They landed on the south coast and routed the imperial forces at the Battle of Nicosia on July 14, 1229. The surviving leaders of the imperial supporters fled to the three mountain castles, Kantara, Buffavento and St. Hilarion. A siege began almost at once that lasted nearly a year. Shortly after Easter in 1230 the Imperial forces surrendered to the Ibelins.

Just two years later, in May 1232, fortunes were reversed. The Imperial forces were on the offensive. With the Lord of Beirut, all his sons and the bulk of his knights struggling to relieve a besieged Beirut, the Imperial forces seized control of Cyprus. The supporters of the Ibelins were forced to seek refuge in St. Hilarion and Buffavento, where they were soon subjected to siege. Six weeks later, after defeating the Imperial forces at the Battle of Argidi on June 15, 1232, the Ibelins were able to lift the siege of St. Hilarion and rescue their women and children.

A long period of peace followed this episode, and St. Hilarion was strengthened and embellished by the Lusignan kings to turn it into an idyllic summer residence high above the heat of the coast. In 1348, King Hugh IV retreated to the castle to escape not an enemy but the plague. During the later Genoese invasion, St. Hilarion was an important royal base of operations, key to disrupting Genoese internal lines of communication.

After that, like Kantara, it lost relevance and fell into disrepair and finally ruin from the 16th century onwards.

St. Hilarion is the setting of important historical events that will be described in future novels, and a setting of minor importance in "The Last Crusader Kingdom."

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

The castle stands 700 meters (2275 feet) above see level on the narrow ridge of the Kyrenia range just slightly southwest of the port of Kyrenia. It was built by the Byzantine governor of the island after the Comnenus emperors re-established full control over Cyprus in the late 10th. Constructed between 1102 and 1110, it was called Didymos by the Byzantines for the twin mountain peaks between which the upper castle sits. The crusaders, however, preferred to call it the castle of "Dieu d'Amour" (the God of Love) and the locals continued to refer to it as St. Hilarion because the saint of that name had built a monastery, been buried and venerated here long before the castle was built.

Remnants of the Castle Church

Remnants of the Castle ChurchThe castle boasts three lines of defense, and was never taken by assault. It was, however, frequently besieged.

View from the upper to the lower ward.

View from the upper to the lower ward.In July/August 1228, after Emperor Friedrich II accused John d'Ibelin of malfeasance and attempted to seize his fief without trial, Ibelin secured control of St. Hilarion, had it well provisioned and moved his and his supporters' dependents there in preparation for a confrontation. Ibelin was persuaded to turn the castle over to the King of Cyprus in exchange for the release of his two hostage sons -- or vice versa, depending on how one interprets the negotiations.

When Friedrich II left the Holy Land for the West, he turned St. Hilarion over to his appointed baillies with orders for them to prevent the Ibelins from setting foot on the island. Within two months, however, the Ibelins had pulled together a sufficient army to challenge this (illegal) order head on. They landed on the south coast and routed the imperial forces at the Battle of Nicosia on July 14, 1229. The surviving leaders of the imperial supporters fled to the three mountain castles, Kantara, Buffavento and St. Hilarion. A siege began almost at once that lasted nearly a year. Shortly after Easter in 1230 the Imperial forces surrendered to the Ibelins.

Just two years later, in May 1232, fortunes were reversed. The Imperial forces were on the offensive. With the Lord of Beirut, all his sons and the bulk of his knights struggling to relieve a besieged Beirut, the Imperial forces seized control of Cyprus. The supporters of the Ibelins were forced to seek refuge in St. Hilarion and Buffavento, where they were soon subjected to siege. Six weeks later, after defeating the Imperial forces at the Battle of Argidi on June 15, 1232, the Ibelins were able to lift the siege of St. Hilarion and rescue their women and children.

A long period of peace followed this episode, and St. Hilarion was strengthened and embellished by the Lusignan kings to turn it into an idyllic summer residence high above the heat of the coast. In 1348, King Hugh IV retreated to the castle to escape not an enemy but the plague. During the later Genoese invasion, St. Hilarion was an important royal base of operations, key to disrupting Genoese internal lines of communication.

After that, like Kantara, it lost relevance and fell into disrepair and finally ruin from the 16th century onwards.

St. Hilarion is the setting of important historical events that will be described in future novels, and a setting of minor importance in "The Last Crusader Kingdom."

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on October 21, 2017 01:00

October 14, 2017

REVIEW of Award-Winning "Envoy of Jerusalem"

Envoy of Jerusalem: Balian d'Ibelin and the Third Crusade

is the winner of seven literary accolades, starting with a B.R.A.G. Medallion. In addition, it took Gold for Biographical Fiction from Pinnacle Awards 2016, Gold for Spiritual/Religious Fiction from Feathered Quill 2017, First in Category for Medieval Fiction from Chaucer Awards 2016, Honorable Mention for Wartime/Military Fiction from Foreword INDIES Awards 2017, Gold for Christian Historical Fiction from Readers' Favorites 2017, and Gold for Biography from Book Excellence Awards 2017.

The following review by Reuben Steenson for the Online Book Club is a good summary of why it found favor with so many literary juries.

Envoy of Jerusalem (subtitled Balian d'Ibelin and the Third Crusade) is the second novel by Helena P. Schrader that I have read, and it is a wonderful book. This novel follows Balian d'Ibelin and a host of other characters in the Holy Lands as they try to recapture cities and strongholds that have been taken by Salah ad-Din, Sultan of Egypt and Damascus. Richard I (known as the Lionheart) is an important presence in the novel, as well as a great number of diverse historical figures. Schrader sticks closely to historical fact - something which her PhD in history qualifies her to do - while weaving in fiction when necessary. For this masterful blend of fact and fiction, the thrilling plot, and Schrader's creation of brilliantly believable characters, I rate Envoy of Jerusalem a flawless 4 out of 4 stars.

The main plot follows Balian d'Ibelin, who features in all three of Schrader's novels in "The Jerusalem Trilogy". Though Envoy of Jerusalemis the third in the trilogy, it reads perfectly well as a standalone novel. I have not yet read the first two books, but had no difficulty understanding the plot. Schrader cunningly weaves in any essential background detail during the action of the novel. Balian is a brave and generous knight who is often faced with difficult choices and challenges. He is an attractive and balanced character, who always chooses the best thing for the people of the land rather than his own selfish gain. He is complemented by his powerful wife and erstwhile Queen of Jerusalem, Maria, who is a focal point for many of the different subplots. Her daughter, Isabella, also features strongly: she is a young princess who learns how to negotiate the world of intrigue and betrayal in upper-class medieval society to become Queen of Jerusalem herself.

I was extremely impressed by Schrader's unparalleled skill in capturing a very complex period in history in a manner that is utterly accessible and even addictive. Little-known characters are brought to the reader's attention, and well-known characters are presented in a new light (for instance Richard I is not portrayed as an unflawed hero, but as a brave, brash king who clashes at times with Balian). All facets of life in the Holy Lands are explored: we are given the stories of highborn nobles, lowly slaves, shop owners, priests, nuns, soldiers, troubadours, adults, children, Christians, Arabs, kings, knights and squires. There is really no corner of the kingdom untouched, or any social strata Schrader does not mention. The result is a satisfying sense of a complete society, and a narrative that lives and breathes with authenticity.

Schrader's style is also delightful - she writes with a simple authority that is perfectly suited to the events that unfold. Her engaging prose shies away from flashy effect, but for me this calm narration actually heightened the emotional impact of the distressing scenes of slavery and warfare, as well as making me trust everything that she said. I found the book extremely difficult to put down, and was glad that it stretched to 500 pages. To write a book of that length without ever losing the reader's interest is no mean feat.

The editing of this book was stellar - I spotted three minor typos in total, and none were particularly jarring. The novel is very well put together, with an abundance of supplementary materials, including a glossary, an introduction, maps, and genealogies, which all further bolstered the reliability of Schrader's narrative. I even enjoyed the attractive font, as well as the little motifs of a horsed knight and a shield that headed new chapters or sections. Schrader is an author who is quickly becoming one of my favourites. Her ability in the field of historical fiction is undeniable, and I look forward to reading several of her other novels in the future. I simply cannot find fault with Envoy of Jerusalem and I warmly recommend it to any fans of historical fiction. It is an exemplary book of its kind.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

The following review by Reuben Steenson for the Online Book Club is a good summary of why it found favor with so many literary juries.

Envoy of Jerusalem (subtitled Balian d'Ibelin and the Third Crusade) is the second novel by Helena P. Schrader that I have read, and it is a wonderful book. This novel follows Balian d'Ibelin and a host of other characters in the Holy Lands as they try to recapture cities and strongholds that have been taken by Salah ad-Din, Sultan of Egypt and Damascus. Richard I (known as the Lionheart) is an important presence in the novel, as well as a great number of diverse historical figures. Schrader sticks closely to historical fact - something which her PhD in history qualifies her to do - while weaving in fiction when necessary. For this masterful blend of fact and fiction, the thrilling plot, and Schrader's creation of brilliantly believable characters, I rate Envoy of Jerusalem a flawless 4 out of 4 stars.

The main plot follows Balian d'Ibelin, who features in all three of Schrader's novels in "The Jerusalem Trilogy". Though Envoy of Jerusalemis the third in the trilogy, it reads perfectly well as a standalone novel. I have not yet read the first two books, but had no difficulty understanding the plot. Schrader cunningly weaves in any essential background detail during the action of the novel. Balian is a brave and generous knight who is often faced with difficult choices and challenges. He is an attractive and balanced character, who always chooses the best thing for the people of the land rather than his own selfish gain. He is complemented by his powerful wife and erstwhile Queen of Jerusalem, Maria, who is a focal point for many of the different subplots. Her daughter, Isabella, also features strongly: she is a young princess who learns how to negotiate the world of intrigue and betrayal in upper-class medieval society to become Queen of Jerusalem herself.

I was extremely impressed by Schrader's unparalleled skill in capturing a very complex period in history in a manner that is utterly accessible and even addictive. Little-known characters are brought to the reader's attention, and well-known characters are presented in a new light (for instance Richard I is not portrayed as an unflawed hero, but as a brave, brash king who clashes at times with Balian). All facets of life in the Holy Lands are explored: we are given the stories of highborn nobles, lowly slaves, shop owners, priests, nuns, soldiers, troubadours, adults, children, Christians, Arabs, kings, knights and squires. There is really no corner of the kingdom untouched, or any social strata Schrader does not mention. The result is a satisfying sense of a complete society, and a narrative that lives and breathes with authenticity.

Schrader's style is also delightful - she writes with a simple authority that is perfectly suited to the events that unfold. Her engaging prose shies away from flashy effect, but for me this calm narration actually heightened the emotional impact of the distressing scenes of slavery and warfare, as well as making me trust everything that she said. I found the book extremely difficult to put down, and was glad that it stretched to 500 pages. To write a book of that length without ever losing the reader's interest is no mean feat.

The editing of this book was stellar - I spotted three minor typos in total, and none were particularly jarring. The novel is very well put together, with an abundance of supplementary materials, including a glossary, an introduction, maps, and genealogies, which all further bolstered the reliability of Schrader's narrative. I even enjoyed the attractive font, as well as the little motifs of a horsed knight and a shield that headed new chapters or sections. Schrader is an author who is quickly becoming one of my favourites. Her ability in the field of historical fiction is undeniable, and I look forward to reading several of her other novels in the future. I simply cannot find fault with Envoy of Jerusalem and I warmly recommend it to any fans of historical fiction. It is an exemplary book of its kind.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on October 14, 2017 01:26

October 7, 2017

"Adventures in Disguise" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

John d'Ibelin is a healthy 14-year-old in a new place. He is curious about his environment and anxious to exploit his growing independence. He also has a secret weapon: Greek.

"Adventures in Disguise"An Excerpt

"Adventures in Disguise"An Excerpt

When John realized that just by changing into a different set of clothes he could also blend in with the native population, he started exploring Nicosia from the ground up―enjoying the utter freedom of anonymity. When John slipped out of the khan in his Greek clothes, he left John d’Ibelin behind, and with him the burden of being the son of the savior of Jerusalem and a paragon of chivalry.

Not that John transformed himself into something despicable or dishonorable. John had not grown into a taste for loose women and had no natural proclivity to alcoholism. Because he was alone on his adventures, he was also not in a position to be led astray. His only companion was [his dog] Barry, who clung to him as loyally as a shadow, ever ready to share a meal―or an adventure.

Today John was looking for firewood. The nights were chilly, and as the frequency of the rain showers increased, the air turned damp as well. The khan provided each resident with an allotment of wood, but it was far too little (in Lord Aimery’s opinion). John wanted to surprise him with a big stack of wood to get them through the next few days. Having no illusions about how much wood he could personally carry, he borrowed a donkey and panniers from the khan and headed toward the outskirts of town where the potters had their kilns. Kilns consume an enormous amount of firewood, and John reckoned he would either encounter one of the suppliers or be able to purchase directly from the kiln enough wood for their modest needs.

Unfortunately, the potters occupied land northeast of Nicosia, so it was a bit of a hike, and John opted to cut through the cattle market and past the slaughterhouse beyond. It was a good place to find a bone or two for Barry, although he disliked the number of beggars that prowled around on the lookout for edible refuse. As always, the beggars clustered near the stinking bins behind the abattoir, and stray dogs licked the blood seeping out of them. Barry lifted his ears and wagged his tail in anticipation, but John braced himself for the smell and tried to hold his breath as he scanned the fresh heaps of bones for the best pieces. He rapidly chose one, handed it off to Barry, and then took a second for later, stashing it into a sack he had over his shoulder. Then he turned away and put a dozen steps’ distance between himself and the bins before letting out his breath.

He found his path was blocked by a young beggar with a bad bruise on the side of his face. John had seen him here several times over the last couple of months, but without the bruise. Evidently he’d run into some kind of trouble. Although he was smaller than John, John guessed they were about the same age. Unlike the younger children, who worked as a pack and had to surrender all their earnings to the adults, this youth usually worked alone.

“I’ve made a collar for the dog,” the beggar announced, holding out a collar made of woven straw with a crude buckle carved from bone. “You can have it for just five obols,” he told John.

John looked down at Barry. The faithful dog did not need a collar; he followed John everywhere without it. On the other hand, John’s mother had taught him that it was better to reward industry than sloth. She always made a point of offering alms to the working poor, or institutions that cared for those not yet or no longer able to work, rather than beggars. She had warned him never to give to children who begged because, she claimed, they only grew up thinking everyone else owed them their livelihood and became thieves and pickpockets. This boy, however, was clearly trying to earn his keep.

Seeing his hesitation, the boy pulled another object out of his pocket. “Or what about a comb?” he asked, offering a comb likewise carved from cattle bone. “It will cost you ten obols.”

“That’s too much,” John protested. The money his father had given him was long since used up (except for the cost of the passage home, still sewn in his boot), and he had to make do with the allowance that Lord Aimery gave him. “Besides,” he added, “I have to get firewood, and I don’t know how much it will cost. Maybe another day.”

“I’ll help you with the firewood,” the boy offered. “I know a place you can get it cheap.”

“I was going to the potters,” John explained.

“They’ll charge you double,” the beggar dismissed the idea. “I know a man who resells wood from damaged structures. There is always some waste he doesn’t care about.”

John weighed whether or not to trust the youth, and decided to go ahead. After all, he had Barry with him and his dagger. “OK.”

The beggar smiled, stuffed the collar and comb back in his pockets, and indicated the way. John fell in beside him with the donkey and Barry trailing. “What’s your name?” he asked the beggar.

“Lakis. And yours?”

“Janis. How did you get that bruise?”

“That bastard Niki tried to take my earnings from me,” Lakis told him bitterly.

“Did he succeed?”

“Sort of. I had some coins hidden.”

“Why do you hang around the slaughterhouse? I’ll bet you could get work somewhere in the city,” John suggested, trying to implement his mother’s policy of encouraging work.

“Where?” Lakis asked back hopefully.

John was embarrassed to have to shrug and admit he didn’t know. “Didn’t you learn a trade?” he asked instead.

“My Dad was a miller,” Lakis declared, his lip a grim line, and he refused to meet John’s eye.

John understood the use of the past tense, and concluded that something terrible had happened to Lakis’ father. After a few minutes of trudging along in silence, John decided to reopen the conversation by asking, “May I see the collar again?”

Lakis brightened up at once, and pulled it out of his pocket. John examined it carefully. The straw collar was only crudely woven, uneven, and not very strong, but the buckle was cleverly made. “You’re good with carving,” John told Lakis. “Where did you learn?”

“After I went to live with my uncle (he’s a butcher in Karpasia), I met this man, a refugee from Jerusalem, who used to collect the bones from behind the butchery so he could carve them into things for sale. He taught me how to make things, but my aunt hated him. She always chased him away whenever she saw him and forbade me from visiting him. She said he was evil, a Musselman.”

“Had he been a slave?” John asked, suspecting this was one of the released captives trying to start his life over again but tainted by six years in Saracen slavery.

“Yes,” Lakis admitted. “He’d learned to carve from the Saracens, only they had ivory rather than bone, he said. He spoke Arabic, but he assured me he was a good Christian.” Lakis sounded uncertain.

“Of course he was,” John defended the unknown man. “Many of our―” John had just been about to say “vassals,” only to realize that would betray that he wasn’t the Greek servant boy he pretended to be.

“What?” Lakis asked.

“Nothing. What happened? I mean, did you disobey your aunt and see the man anyway?”

“Yes, until she caught me and had my uncle beat me. It was terrible, and I hated it there, anyway. I don’t want to be a butcher, and my cousins will inherit anyway, so what’s the point?”

“You should apprentice to a carver―someone who makes book covers or the like,” John decided enthusiastically, thinking of the magnificent carved ivory cover of one of his mother’s books.

“Book covers?” Lakis asked in a skeptical tone.

John suspected he’d given himself away again. “Or combs or whatever,” he added with a dismissive gesture.

“What’s your trade?” Lakis countered.

“Me?” John shrugged. “I’m just a servant. How far is it to this place with the firewood?”

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

"Adventures in Disguise"An Excerpt

"Adventures in Disguise"An Excerpt When John realized that just by changing into a different set of clothes he could also blend in with the native population, he started exploring Nicosia from the ground up―enjoying the utter freedom of anonymity. When John slipped out of the khan in his Greek clothes, he left John d’Ibelin behind, and with him the burden of being the son of the savior of Jerusalem and a paragon of chivalry.

Not that John transformed himself into something despicable or dishonorable. John had not grown into a taste for loose women and had no natural proclivity to alcoholism. Because he was alone on his adventures, he was also not in a position to be led astray. His only companion was [his dog] Barry, who clung to him as loyally as a shadow, ever ready to share a meal―or an adventure.

Today John was looking for firewood. The nights were chilly, and as the frequency of the rain showers increased, the air turned damp as well. The khan provided each resident with an allotment of wood, but it was far too little (in Lord Aimery’s opinion). John wanted to surprise him with a big stack of wood to get them through the next few days. Having no illusions about how much wood he could personally carry, he borrowed a donkey and panniers from the khan and headed toward the outskirts of town where the potters had their kilns. Kilns consume an enormous amount of firewood, and John reckoned he would either encounter one of the suppliers or be able to purchase directly from the kiln enough wood for their modest needs.

Unfortunately, the potters occupied land northeast of Nicosia, so it was a bit of a hike, and John opted to cut through the cattle market and past the slaughterhouse beyond. It was a good place to find a bone or two for Barry, although he disliked the number of beggars that prowled around on the lookout for edible refuse. As always, the beggars clustered near the stinking bins behind the abattoir, and stray dogs licked the blood seeping out of them. Barry lifted his ears and wagged his tail in anticipation, but John braced himself for the smell and tried to hold his breath as he scanned the fresh heaps of bones for the best pieces. He rapidly chose one, handed it off to Barry, and then took a second for later, stashing it into a sack he had over his shoulder. Then he turned away and put a dozen steps’ distance between himself and the bins before letting out his breath.

He found his path was blocked by a young beggar with a bad bruise on the side of his face. John had seen him here several times over the last couple of months, but without the bruise. Evidently he’d run into some kind of trouble. Although he was smaller than John, John guessed they were about the same age. Unlike the younger children, who worked as a pack and had to surrender all their earnings to the adults, this youth usually worked alone.

“I’ve made a collar for the dog,” the beggar announced, holding out a collar made of woven straw with a crude buckle carved from bone. “You can have it for just five obols,” he told John.

John looked down at Barry. The faithful dog did not need a collar; he followed John everywhere without it. On the other hand, John’s mother had taught him that it was better to reward industry than sloth. She always made a point of offering alms to the working poor, or institutions that cared for those not yet or no longer able to work, rather than beggars. She had warned him never to give to children who begged because, she claimed, they only grew up thinking everyone else owed them their livelihood and became thieves and pickpockets. This boy, however, was clearly trying to earn his keep.

Seeing his hesitation, the boy pulled another object out of his pocket. “Or what about a comb?” he asked, offering a comb likewise carved from cattle bone. “It will cost you ten obols.”

“That’s too much,” John protested. The money his father had given him was long since used up (except for the cost of the passage home, still sewn in his boot), and he had to make do with the allowance that Lord Aimery gave him. “Besides,” he added, “I have to get firewood, and I don’t know how much it will cost. Maybe another day.”

“I’ll help you with the firewood,” the boy offered. “I know a place you can get it cheap.”

“I was going to the potters,” John explained.

“They’ll charge you double,” the beggar dismissed the idea. “I know a man who resells wood from damaged structures. There is always some waste he doesn’t care about.”

John weighed whether or not to trust the youth, and decided to go ahead. After all, he had Barry with him and his dagger. “OK.”

The beggar smiled, stuffed the collar and comb back in his pockets, and indicated the way. John fell in beside him with the donkey and Barry trailing. “What’s your name?” he asked the beggar.

“Lakis. And yours?”

“Janis. How did you get that bruise?”

“That bastard Niki tried to take my earnings from me,” Lakis told him bitterly.

“Did he succeed?”

“Sort of. I had some coins hidden.”

“Why do you hang around the slaughterhouse? I’ll bet you could get work somewhere in the city,” John suggested, trying to implement his mother’s policy of encouraging work.

“Where?” Lakis asked back hopefully.

John was embarrassed to have to shrug and admit he didn’t know. “Didn’t you learn a trade?” he asked instead.

“My Dad was a miller,” Lakis declared, his lip a grim line, and he refused to meet John’s eye.

John understood the use of the past tense, and concluded that something terrible had happened to Lakis’ father. After a few minutes of trudging along in silence, John decided to reopen the conversation by asking, “May I see the collar again?”

Lakis brightened up at once, and pulled it out of his pocket. John examined it carefully. The straw collar was only crudely woven, uneven, and not very strong, but the buckle was cleverly made. “You’re good with carving,” John told Lakis. “Where did you learn?”

“After I went to live with my uncle (he’s a butcher in Karpasia), I met this man, a refugee from Jerusalem, who used to collect the bones from behind the butchery so he could carve them into things for sale. He taught me how to make things, but my aunt hated him. She always chased him away whenever she saw him and forbade me from visiting him. She said he was evil, a Musselman.”

“Had he been a slave?” John asked, suspecting this was one of the released captives trying to start his life over again but tainted by six years in Saracen slavery.

“Yes,” Lakis admitted. “He’d learned to carve from the Saracens, only they had ivory rather than bone, he said. He spoke Arabic, but he assured me he was a good Christian.” Lakis sounded uncertain.

“Of course he was,” John defended the unknown man. “Many of our―” John had just been about to say “vassals,” only to realize that would betray that he wasn’t the Greek servant boy he pretended to be.

“What?” Lakis asked.

“Nothing. What happened? I mean, did you disobey your aunt and see the man anyway?”

“Yes, until she caught me and had my uncle beat me. It was terrible, and I hated it there, anyway. I don’t want to be a butcher, and my cousins will inherit anyway, so what’s the point?”

“You should apprentice to a carver―someone who makes book covers or the like,” John decided enthusiastically, thinking of the magnificent carved ivory cover of one of his mother’s books.

“Book covers?” Lakis asked in a skeptical tone.

John suspected he’d given himself away again. “Or combs or whatever,” he added with a dismissive gesture.

“What’s your trade?” Lakis countered.

“Me?” John shrugged. “I’m just a servant. How far is it to this place with the firewood?”

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on October 07, 2017 02:53

September 30, 2017

Characters in "The Last Crusader Kingdom:" Lakis

Turning from the historical to the fictional characters in the Last Crusader Kingdom, I want to start with Lakis the Orphan. Lakis is the second character introduced in the novel, making his first appearance in the Prologue.

Lakis' function in the novel is two-fold. He represents on one hand a youth of the working class and on the other the Greek victims of the insurgency.

When John first encounters Lakis, John has disguised himself as a servant. This enables him to mingle with people he would not otherwise meet. Because a servant is less intimidating to the beggared Lakis, John is able to win a decree of trust. Through Lakis, John has a glimpse of the lives of working people.

More important, however, Lakis is a victim of the ongoing civil war on Cyprus. His parents, home and future-livelihood have been destroyed in a reprisal raid by Guy de Lusignan's men. Significantly, the raid was led by John's cousin Henri de Brie, which gives John a sense of guilt for what happened. This, in turn, makes him ask more questions and look for solutions as he might otherwise not have done. In short, Lakis gives the Greek Orthodox population a face. The abstract wrongs Aimery and others bemoan are suddenly more real for John -- and the reader.

Lakis also serves as the bridge between the two worlds as well. Through him, Balian is able to make contact with the leader of the rebels. Yet, Lakis continues to inhabit a different world from John. Once John's true identity is revealed, there can be no more friendship, only patronage. Thus John's relationship with Lakis is a measure of his level of responsibility and so his progress on the road to his destiny as a leading baron in two kingdoms.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Lakis' function in the novel is two-fold. He represents on one hand a youth of the working class and on the other the Greek victims of the insurgency.

When John first encounters Lakis, John has disguised himself as a servant. This enables him to mingle with people he would not otherwise meet. Because a servant is less intimidating to the beggared Lakis, John is able to win a decree of trust. Through Lakis, John has a glimpse of the lives of working people.

More important, however, Lakis is a victim of the ongoing civil war on Cyprus. His parents, home and future-livelihood have been destroyed in a reprisal raid by Guy de Lusignan's men. Significantly, the raid was led by John's cousin Henri de Brie, which gives John a sense of guilt for what happened. This, in turn, makes him ask more questions and look for solutions as he might otherwise not have done. In short, Lakis gives the Greek Orthodox population a face. The abstract wrongs Aimery and others bemoan are suddenly more real for John -- and the reader.

Lakis also serves as the bridge between the two worlds as well. Through him, Balian is able to make contact with the leader of the rebels. Yet, Lakis continues to inhabit a different world from John. Once John's true identity is revealed, there can be no more friendship, only patronage. Thus John's relationship with Lakis is a measure of his level of responsibility and so his progress on the road to his destiny as a leading baron in two kingdoms.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on September 30, 2017 01:43

September 23, 2017

"The Limits of Loyalty" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

Richard the Lionheart sold Cyprus to Guy de Lusignan, and at the latter's death less than two years later, Guy named his brother Geoffrey his heir. Aimery -- who had brought Guy out to the Holy Land to make his fortune, who had supported his usurpation of the crown of Jerusalem, fought with him at Hattin and suffered captivity with him -- was left out in the cold.In this excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom" Aimery has returned to Acre, broken by his brother's ingratitude.

Balian came to a stop in front of Aimery and Eschiva, and the older man looked up at him grimly, unsure what he should say. Part of him wanted to blame Ibelin for sending him to Cyprus in the first place. He should have stayed and defended his innocence before the High Court. He should never have resigned as Constable. He should--

"Look, Aimery, your idiot brother may have named Geoffrey his heir, but I wouldn't bet on his chances of ever claiming that inheritance."

"Why not?" Aimery snapped back, frowning. "What do you mean?"

"Do you honestly think that the men who have spent the better part of two years fighting to gain control of Cyprus are about to relinquish their gains -- or claims -- to someone who hasn't been risking his hide with them? My nephew Henri, you can be damned sure, wouldn't dream of such a thing, not even in a nightmare."

Aimery's eyes narrowed, and he slowly withdrew his arm from Eschiva to sit tensely focused on Ibelin. "What are you saying?"

"How many times in the history of this Kingdom have men from the West been the 'rightful' heir, only to lose out to men already here? The precedent was set from the very start with the election of Baldwin I. Now is no different. My nephew, Toron, Cheneche, Bethsan, even Barlais -- they know you, they trust you, and they respect you. If you want them to recognize you as Guy's heir, do what Guy, in his stubborn idiocy, wouldn't do: give them each enough land so they can feel richly rewarded, and keep enough for yourself to win new vassals. This city and Tyre are flooded with men who have lost everything. If you promise them something, anything, just a foothold, they will flood to your banner. They will practically swim to Cyprus for the chance of a new beginning." Maria Zoe found herself wondering if her husband was speaking for himself.

Balian continued, "You've been a loyal brother, Aimery. Again and again, you backed Guy against your better judgement. You stayed by him on the Horns of Hattin, when you could have broken out with Tripoli or me. You were in captivity with him. You joined him at the siege of Acre. You supported him against Montferrat. And what did he ever give you in return? Nothing. Note one miserable thing. Why, in the name of our ever-loving Christ, should you respect his last wishes?"

"You sincerely think your nephew you back me?"

"For a barony? Henri would back John's dog!"

Suddenly they were all laughing, and although Aimery growled, "I'm not sure that's much of a compliment," his shoulders had squared, and Eschiva could feel the energy surging through his muscles again.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Balian came to a stop in front of Aimery and Eschiva, and the older man looked up at him grimly, unsure what he should say. Part of him wanted to blame Ibelin for sending him to Cyprus in the first place. He should have stayed and defended his innocence before the High Court. He should never have resigned as Constable. He should--

"Look, Aimery, your idiot brother may have named Geoffrey his heir, but I wouldn't bet on his chances of ever claiming that inheritance."

"Why not?" Aimery snapped back, frowning. "What do you mean?"

"Do you honestly think that the men who have spent the better part of two years fighting to gain control of Cyprus are about to relinquish their gains -- or claims -- to someone who hasn't been risking his hide with them? My nephew Henri, you can be damned sure, wouldn't dream of such a thing, not even in a nightmare."

Aimery's eyes narrowed, and he slowly withdrew his arm from Eschiva to sit tensely focused on Ibelin. "What are you saying?"

"How many times in the history of this Kingdom have men from the West been the 'rightful' heir, only to lose out to men already here? The precedent was set from the very start with the election of Baldwin I. Now is no different. My nephew, Toron, Cheneche, Bethsan, even Barlais -- they know you, they trust you, and they respect you. If you want them to recognize you as Guy's heir, do what Guy, in his stubborn idiocy, wouldn't do: give them each enough land so they can feel richly rewarded, and keep enough for yourself to win new vassals. This city and Tyre are flooded with men who have lost everything. If you promise them something, anything, just a foothold, they will flood to your banner. They will practically swim to Cyprus for the chance of a new beginning." Maria Zoe found herself wondering if her husband was speaking for himself.

Balian continued, "You've been a loyal brother, Aimery. Again and again, you backed Guy against your better judgement. You stayed by him on the Horns of Hattin, when you could have broken out with Tripoli or me. You were in captivity with him. You joined him at the siege of Acre. You supported him against Montferrat. And what did he ever give you in return? Nothing. Note one miserable thing. Why, in the name of our ever-loving Christ, should you respect his last wishes?"

"You sincerely think your nephew you back me?"

"For a barony? Henri would back John's dog!"

Suddenly they were all laughing, and although Aimery growled, "I'm not sure that's much of a compliment," his shoulders had squared, and Eschiva could feel the energy surging through his muscles again.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on September 23, 2017 01:24