Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 39

September 16, 2017

Inspirational Settings - Kantara

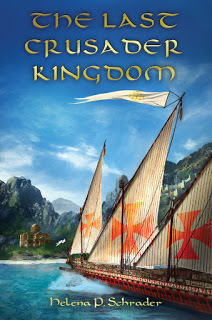

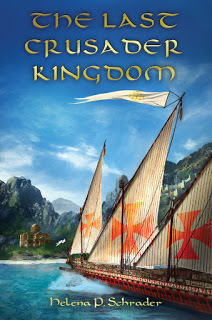

As I've noted elsewhere, I have often found historical places inspiring. Kantara is one of those places. I fell so in love with this castle on Cyprus that it is almost possible to say that is responsible for my entire series of novels set on Cyprus -- but not quite. Other places on the island (that I will introduce you to later) also played their part. Nevertheless, many of the characters and events my readers will discover both in "The Last Crusader Kingdom" and "The Lion of Karpas" sprang from the mists that swirl around Kantara.

Here is a brief history.

The view up to the castle.

Kantara is located on the tip of a long, narrow ridge as the Kyrenia mountain range comes to an abrupt end overlooking the plain of Karpas. It sits 630 meters (2,067 feet) above the Mediterranean.

And the View Down to the Sea

Although the fundamental structure was constructed under the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus after the Greek Empire re-established firm control over the island of Cyprus, the name is thought to derive from Arab the words "kandara" (high building) or "kandak" (castle). This suggests there may have been an earlier structure, an outpost or watch tower, that occupied this strategic location before the Comnenus Emperor constructed a full-fledged castle.

During Richard the Lionheart's invasion of Cyprus in 1191, Kantara served as a temporary refuge for the Greek tyrant Isaac Comnenus and not even the great Lionheart made any attempt to take it. Then again, he didn't need too. He captured the seaside fortress of Kyrenia instead and with it Isaac's beloved daughter. The tyrant submitted without any further resistance after his daughter's capture.

During the bitter wars between Emperor Friedrich II and the barons, on the other hand, the castle of Kantara was subjected to a long and brutal siege. Defended by men loyal to the German emperor, the barons of Cyprus placed the siege under the command of Anseau de Brie. Brie built a trebuchet that, according to the contemporary chronicler and witness Philip de Novare (a fighting man in the service of the Ibelins), "battered down nearly all the walls." While this was doubtless an exaggeration, Ibelin also reports that the bedrock on and into which the castle was built defied destruction. Multiple attempts at assaulting the castle were successfully repulsed.

During the bitter wars between Emperor Friedrich II and the barons, on the other hand, the castle of Kantara was subjected to a long and brutal siege. Defended by men loyal to the German emperor, the barons of Cyprus placed the siege under the command of Anseau de Brie. Brie built a trebuchet that, according to the contemporary chronicler and witness Philip de Novare (a fighting man in the service of the Ibelins), "battered down nearly all the walls." While this was doubtless an exaggeration, Ibelin also reports that the bedrock on and into which the castle was built defied destruction. Multiple attempts at assaulting the castle were successfully repulsed.

The castle only surrendered after ten months of siege due primarily to dwindling supplies and the demoralization of the garrison after the death of their commander, Gauvain de Cheveche.

During the Genoese occupation of Cyprus in late 15th century, the castle was held for the crown and was twice attacked by Genoese forces. It resisted both assaults successfully, and became the base for counter-attacks, preventing Genoese control of the Karpas peninsula.

After the collapse of Lusignan rule on Cyprus and the establishment of Venetian control in the 16th Century, the castle was abandoned and began to decay.

Left behind were the impressive structures that gradually became ruins and the legends. It was referred to by locals as "the castle of a hundred chambers" -- although according to legend the 101st chamber contained a treasure that no one had ever found. Or, alternatively, the 101st chamber was enchanted and if one fell asleep in it, one woke up years later in a lovely garden. Another local name for the castle was "the house/residence of the queen" -- although no specific queen appears to be associated with the castle historically.

The 19th century traveler D. Hogarth combines these themes suggesting: "...the traveler might imagine it the stronghold of a Sleeping Beauty, untouched by change or time for a thousand years."

Kantara certainly captured my imagination and my heart. It is the setting of many episodes of the (unpublished) "Lion of Karpas" and has a modest role in "The Last Crusader Kingdom."

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Here is a brief history.

The view up to the castle.

Kantara is located on the tip of a long, narrow ridge as the Kyrenia mountain range comes to an abrupt end overlooking the plain of Karpas. It sits 630 meters (2,067 feet) above the Mediterranean.

And the View Down to the Sea

Although the fundamental structure was constructed under the Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus after the Greek Empire re-established firm control over the island of Cyprus, the name is thought to derive from Arab the words "kandara" (high building) or "kandak" (castle). This suggests there may have been an earlier structure, an outpost or watch tower, that occupied this strategic location before the Comnenus Emperor constructed a full-fledged castle.

During Richard the Lionheart's invasion of Cyprus in 1191, Kantara served as a temporary refuge for the Greek tyrant Isaac Comnenus and not even the great Lionheart made any attempt to take it. Then again, he didn't need too. He captured the seaside fortress of Kyrenia instead and with it Isaac's beloved daughter. The tyrant submitted without any further resistance after his daughter's capture.

During the bitter wars between Emperor Friedrich II and the barons, on the other hand, the castle of Kantara was subjected to a long and brutal siege. Defended by men loyal to the German emperor, the barons of Cyprus placed the siege under the command of Anseau de Brie. Brie built a trebuchet that, according to the contemporary chronicler and witness Philip de Novare (a fighting man in the service of the Ibelins), "battered down nearly all the walls." While this was doubtless an exaggeration, Ibelin also reports that the bedrock on and into which the castle was built defied destruction. Multiple attempts at assaulting the castle were successfully repulsed.

During the bitter wars between Emperor Friedrich II and the barons, on the other hand, the castle of Kantara was subjected to a long and brutal siege. Defended by men loyal to the German emperor, the barons of Cyprus placed the siege under the command of Anseau de Brie. Brie built a trebuchet that, according to the contemporary chronicler and witness Philip de Novare (a fighting man in the service of the Ibelins), "battered down nearly all the walls." While this was doubtless an exaggeration, Ibelin also reports that the bedrock on and into which the castle was built defied destruction. Multiple attempts at assaulting the castle were successfully repulsed.

The castle only surrendered after ten months of siege due primarily to dwindling supplies and the demoralization of the garrison after the death of their commander, Gauvain de Cheveche.

During the Genoese occupation of Cyprus in late 15th century, the castle was held for the crown and was twice attacked by Genoese forces. It resisted both assaults successfully, and became the base for counter-attacks, preventing Genoese control of the Karpas peninsula.

After the collapse of Lusignan rule on Cyprus and the establishment of Venetian control in the 16th Century, the castle was abandoned and began to decay.

Left behind were the impressive structures that gradually became ruins and the legends. It was referred to by locals as "the castle of a hundred chambers" -- although according to legend the 101st chamber contained a treasure that no one had ever found. Or, alternatively, the 101st chamber was enchanted and if one fell asleep in it, one woke up years later in a lovely garden. Another local name for the castle was "the house/residence of the queen" -- although no specific queen appears to be associated with the castle historically.

The 19th century traveler D. Hogarth combines these themes suggesting: "...the traveler might imagine it the stronghold of a Sleeping Beauty, untouched by change or time for a thousand years."

Kantara certainly captured my imagination and my heart. It is the setting of many episodes of the (unpublished) "Lion of Karpas" and has a modest role in "The Last Crusader Kingdom."

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on September 16, 2017 01:44

September 8, 2017

"Fathers and Sons" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

It is never easy being 14, but in the Middle Ages boys of 14 were expected to start learning their trade in earnest. For youth from the feudal elite, that meant learning the trade of knighthood by serving as a squire to another knight. Most commonly, boys served a relative in this capacity, if possible a relative of higher status. The decision, however, was made by parents not the youth involved.

In this excerpt, John d'Ibelin has broken the rules and now must face his father.

"Fathers and Sons"An Excerpt

“Please, my lord,” John pleaded earnestly with his father. He was dressed in his chain-mail hauberk and straining to look as mature as possible. “I want to go with Lord Aimery. It’s my place. As his squire.”

Balian frowned. Watching his eldest son grow into a resourceful, responsible, and yet optimistic young man was one of his greatest joys. He did not like being separated from John at all, but up to now he’d been in Acre, only a few hours away. Balian had been able to visit him, or call him home, on short notice. Cyprus was different. Cyprus was across the water, a strange and unfamiliar place. He knew Aimery would do his best to look out for John, but ultimately they were both at the mercy of Guy de Lusignan—the last man on earth Balian trusted.

“Has Lord Aimery asked you to go with him?” Balian growled, preparing to give the former Constable a piece of his mind.

“No, he didn’t. He told me I was released from his service, but I―I told him I wanted to go with him.” John stumbled a little over his words.

Balian knew his son well, and by his reaction quickly guessed he had already pledged himself to Aimery. “Did you give him your word?”

John swallowed guiltily, but stood his ground. “Yes, my lord.”

“You had no right to do that without my permission,” Balian reminded his son sharply.

“My lord—Papa—Lord Aimery’s completely alone! You know how much Guy hates him. He’s as likely to throw Lord Aimery out of his court as Champagne did―”

“Yes, exactly, so what good will you being there do?” Balian retorted dismissively.

To his father’s astonishment, John had a ready answer. Meeting his father’s eye, John declared firmly, “I can make sure his armor glistens and his spurs gleam and ensure that no one can sneer at him for a beggar. I can show him the respect he deserves, and in so doing shame them. Most of all, I can remind them of where you stand, my lord. I can remind them that the Lord of Ibelin holds Aimery de Lusignan in greater honor than either claimant to the crown of Jerusalem.”

Balian caught his breath and held it. When he let it out it was with a sense of rueful respect. “If you don’t master the sword and lance, John, you can make your living in the courts.”

“Does that mean I can go with Lord Aimery?” John jumped at the unspoken shift in his father’s stance.

“Yes, damn it. It means you may go with him, but don’t think I can’t come after you! If I have any reason to think you’re not safe, not keeping good company, or not remembering your duty to God, I will haul you back to Caymont and make you dig irrigation ditches with me!”

John broke into a smile of relief and excitement. He flung his arms around his father with a heartfelt, “Thank you, Papa! You won’t regret this! Wait and see―Lord Aimery plans to demand land from his brother, and when he does, he’ll reward me, too. We’ll have something for Philip and a dowry for Margaret. I promise you, Papa, I’ll make our family richer and stronger!”

Balian shook his head at so much youthful optimism and enthusiasm, but held his son tight for a moment before stepping back with sigh of resignation and capitulation to warn, “You’re very young, John. You have a lot to learn, and not all of what you need to learn will be pleasant. Whatever happens, remember who you are: that the blood of the Eastern Roman Emperors runs in your veins.”

John sobered immediately and looked at his father squarely and earnestly. “I won’t forget that; but even more, I won’t forget that I am the son of Balian d’Ibelin, the man who saved the peopleof Jerusalem.”

The unexpected blow almost felled his father. He could only defend himself by embracing his son a second time in gratitude and pride.

Buy Now!

In this excerpt, John d'Ibelin has broken the rules and now must face his father.

"Fathers and Sons"An Excerpt

“Please, my lord,” John pleaded earnestly with his father. He was dressed in his chain-mail hauberk and straining to look as mature as possible. “I want to go with Lord Aimery. It’s my place. As his squire.”

Balian frowned. Watching his eldest son grow into a resourceful, responsible, and yet optimistic young man was one of his greatest joys. He did not like being separated from John at all, but up to now he’d been in Acre, only a few hours away. Balian had been able to visit him, or call him home, on short notice. Cyprus was different. Cyprus was across the water, a strange and unfamiliar place. He knew Aimery would do his best to look out for John, but ultimately they were both at the mercy of Guy de Lusignan—the last man on earth Balian trusted.

“Has Lord Aimery asked you to go with him?” Balian growled, preparing to give the former Constable a piece of his mind.

“No, he didn’t. He told me I was released from his service, but I―I told him I wanted to go with him.” John stumbled a little over his words.

Balian knew his son well, and by his reaction quickly guessed he had already pledged himself to Aimery. “Did you give him your word?”

John swallowed guiltily, but stood his ground. “Yes, my lord.”

“You had no right to do that without my permission,” Balian reminded his son sharply.

“My lord—Papa—Lord Aimery’s completely alone! You know how much Guy hates him. He’s as likely to throw Lord Aimery out of his court as Champagne did―”

“Yes, exactly, so what good will you being there do?” Balian retorted dismissively.

To his father’s astonishment, John had a ready answer. Meeting his father’s eye, John declared firmly, “I can make sure his armor glistens and his spurs gleam and ensure that no one can sneer at him for a beggar. I can show him the respect he deserves, and in so doing shame them. Most of all, I can remind them of where you stand, my lord. I can remind them that the Lord of Ibelin holds Aimery de Lusignan in greater honor than either claimant to the crown of Jerusalem.”

Balian caught his breath and held it. When he let it out it was with a sense of rueful respect. “If you don’t master the sword and lance, John, you can make your living in the courts.”

“Does that mean I can go with Lord Aimery?” John jumped at the unspoken shift in his father’s stance.

“Yes, damn it. It means you may go with him, but don’t think I can’t come after you! If I have any reason to think you’re not safe, not keeping good company, or not remembering your duty to God, I will haul you back to Caymont and make you dig irrigation ditches with me!”

John broke into a smile of relief and excitement. He flung his arms around his father with a heartfelt, “Thank you, Papa! You won’t regret this! Wait and see―Lord Aimery plans to demand land from his brother, and when he does, he’ll reward me, too. We’ll have something for Philip and a dowry for Margaret. I promise you, Papa, I’ll make our family richer and stronger!”

Balian shook his head at so much youthful optimism and enthusiasm, but held his son tight for a moment before stepping back with sigh of resignation and capitulation to warn, “You’re very young, John. You have a lot to learn, and not all of what you need to learn will be pleasant. Whatever happens, remember who you are: that the blood of the Eastern Roman Emperors runs in your veins.”

John sobered immediately and looked at his father squarely and earnestly. “I won’t forget that; but even more, I won’t forget that I am the son of Balian d’Ibelin, the man who saved the peopleof Jerusalem.”

The unexpected blow almost felled his father. He could only defend himself by embracing his son a second time in gratitude and pride.

Buy Now!

Published on September 08, 2017 23:57

The Last Crusader Kingdom: "Fathers and Sons" - Excerpt 3

The Last Crusader Kingdom

"Fathers and Sons"An Excerpt

“Please, my lord,” John pleaded earnestly with his father. He was dressed in his chain-mail hauberk and straining to look as mature as possible. “I want to go with Lord Aimery. It’s my place. As his squire.”

Balian frowned. Watching his eldest son grow into a resourceful, responsible, and yet optimistic young man was one of his greatest joys. He did not like being separated from John at all, but up to now he’d been in Acre, only a few hours away. Balian had been able to visit him, or call him home, on short notice. Cyprus was different. Cyprus was across the water, a strange and unfamiliar place. He knew Aimery would do his best to look out for John, but ultimately they were both at the mercy of Guy de Lusignan—the last man on earth Balian trusted.

“Has Lord Aimery asked you to go with him?” Balian growled, preparing to give the former Constable a piece of his mind.

“No, he didn’t. He told me I was released from his service, but I―I told him I wanted to go with him.” John stumbled a little over his words.

Balian knew his son well, and by his reaction quickly guessed he had already pledged himself to Aimery. “Did you give him your word?”

John swallowed guiltily, but stood his ground. “Yes, my lord.”

“You had no right to do that without my permission,” Balian reminded his son sharply.

“My lord—Papa—Lord Aimery’s completely alone! You know how much Guy hates him. He’s as likely to throw Lord Aimery out of his court as Champagne did―”

“Yes, exactly, so what good will you being there do?” Balian retorted dismissively.

To his father’s astonishment, John had a ready answer. Meeting his father’s eye, John declared firmly, “I can make sure his armor glistens and his spurs gleam and ensure that no one can sneer at him for a beggar. I can show him the respect he deserves, and in so doing shame them. Most of all, I can remind them of where you stand, my lord. I can remind them that the Lord of Ibelin holds Aimery de Lusignan in greater honor than either claimant to the crown of Jerusalem.”

Balian caught his breath and held it. When he let it out it was with a sense of rueful respect. “If you don’t master the sword and lance, John, you can make your living in the courts.”

“Does that mean I can go with Lord Aimery?” John jumped at the unspoken shift in his father’s stance.

“Yes, damn it. It means you may go with him, but don’t think I can’t come after you! If I have any reason to think you’re not safe, not keeping good company, or not remembering your duty to God, I will haul you back to Caymont and make you dig irrigation ditches with me!”

John broke into a smile of relief and excitement. He flung his arms around his father with a heartfelt, “Thank you, Papa! You won’t regret this! Wait and see―Lord Aimery plans to demand land from his brother, and when he does, he’ll reward me, too. We’ll have something for Philip and a dowry for Margaret. I promise you, Papa, I’ll make our family richer and stronger!”

Balian shook his head at so much youthful optimism and enthusiasm, but held his son tight for a moment before stepping back with sigh of resignation and capitulation to warn, “You’re very young, John. You have a lot to learn, and not all of what you need to learn will be pleasant. Whatever happens, remember who you are: that the blood of the Eastern Roman Emperors runs in your veins.”

John sobered immediately and looked at his father squarely and earnestly. “I won’t forget that; but even more, I won’t forget that I am the son of Balian d’Ibelin, the man who saved the peopleof Jerusalem.”

The unexpected blow almost felled his father. He could only defend himself by embracing his son a second time in gratitude and pride.

Buy Now!

"Fathers and Sons"An Excerpt

“Please, my lord,” John pleaded earnestly with his father. He was dressed in his chain-mail hauberk and straining to look as mature as possible. “I want to go with Lord Aimery. It’s my place. As his squire.”

Balian frowned. Watching his eldest son grow into a resourceful, responsible, and yet optimistic young man was one of his greatest joys. He did not like being separated from John at all, but up to now he’d been in Acre, only a few hours away. Balian had been able to visit him, or call him home, on short notice. Cyprus was different. Cyprus was across the water, a strange and unfamiliar place. He knew Aimery would do his best to look out for John, but ultimately they were both at the mercy of Guy de Lusignan—the last man on earth Balian trusted.

“Has Lord Aimery asked you to go with him?” Balian growled, preparing to give the former Constable a piece of his mind.

“No, he didn’t. He told me I was released from his service, but I―I told him I wanted to go with him.” John stumbled a little over his words.

Balian knew his son well, and by his reaction quickly guessed he had already pledged himself to Aimery. “Did you give him your word?”

John swallowed guiltily, but stood his ground. “Yes, my lord.”

“You had no right to do that without my permission,” Balian reminded his son sharply.

“My lord—Papa—Lord Aimery’s completely alone! You know how much Guy hates him. He’s as likely to throw Lord Aimery out of his court as Champagne did―”

“Yes, exactly, so what good will you being there do?” Balian retorted dismissively.

To his father’s astonishment, John had a ready answer. Meeting his father’s eye, John declared firmly, “I can make sure his armor glistens and his spurs gleam and ensure that no one can sneer at him for a beggar. I can show him the respect he deserves, and in so doing shame them. Most of all, I can remind them of where you stand, my lord. I can remind them that the Lord of Ibelin holds Aimery de Lusignan in greater honor than either claimant to the crown of Jerusalem.”

Balian caught his breath and held it. When he let it out it was with a sense of rueful respect. “If you don’t master the sword and lance, John, you can make your living in the courts.”

“Does that mean I can go with Lord Aimery?” John jumped at the unspoken shift in his father’s stance.

“Yes, damn it. It means you may go with him, but don’t think I can’t come after you! If I have any reason to think you’re not safe, not keeping good company, or not remembering your duty to God, I will haul you back to Caymont and make you dig irrigation ditches with me!”

John broke into a smile of relief and excitement. He flung his arms around his father with a heartfelt, “Thank you, Papa! You won’t regret this! Wait and see―Lord Aimery plans to demand land from his brother, and when he does, he’ll reward me, too. We’ll have something for Philip and a dowry for Margaret. I promise you, Papa, I’ll make our family richer and stronger!”

Balian shook his head at so much youthful optimism and enthusiasm, but held his son tight for a moment before stepping back with sigh of resignation and capitulation to warn, “You’re very young, John. You have a lot to learn, and not all of what you need to learn will be pleasant. Whatever happens, remember who you are: that the blood of the Eastern Roman Emperors runs in your veins.”

John sobered immediately and looked at his father squarely and earnestly. “I won’t forget that; but even more, I won’t forget that I am the son of Balian d’Ibelin, the man who saved the peopleof Jerusalem.”

The unexpected blow almost felled his father. He could only defend himself by embracing his son a second time in gratitude and pride.

Buy Now!

Published on September 08, 2017 23:57

September 2, 2017

Characters in The Last Crusader Kingdom: St. Neophytos

The role of the Greek Orthodox Church in the popular opposition to Frankish rule on Cyprus is an important feature of The Last Crusader Kingdom. As explained earlier, this hypothesis was based on the fact that the only named rebel was a priest and that the Greek aristocracy had largely withdrawn to Constantinople. Yet the idea was also influenced by the fact that the only contemporary Cypriot chronicle for this period was written by a hermit monk named Neophytos.

In contrast to the Latin and French chronicles (that in a sentence or two claim that the people of Cyprus welcomed Guy de Lusignan―after driving out the Templars―and every one lived happily ever after), Neophytos’ account suggests an extended period of oppression, resistance, violence and struggle. To be sure, Neophytos’ descriptions of all the twelfth century rulers of Cyprus are negative and his commentary on contemporary events is characterized by a pervasive sense of gloom and impending doom.

Yet the fact remains: he was living on Cyprus during the period described in the novel. As such he is the only eye-witness of events that we can still “hear from” today―and he describes the increasing lawlessness and deterioration of governance that is a major theme of my novel.

Furthermore, he was known to have traveled to the Kingdom of Jerusalem in his youth, giving him at least a little insight into what the Kingdom of Jerusalem was like. Most important, he received many visitors to his hermitage in the period of the novel. The temptation to have Balian meet him face to face was too great to resist!

The historical Neophytos was born to a peasant family in the Cypriot mountains in 1134. He, like his parents, was illiterate. At the age of 18 he caused a major scandal by running away to a monastery to avoid an arranged marriage. Because he was illiterate, he was initially assigned to tend the monastery vineyard, but after five years he had learned to read and write sufficiently to be made assistant sacristan. He performed these duties for two years, but then he expressed his desire to become a hermit. His superiors did not think he was ripe enough at the age of 25 for such a life, so instead sent him on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He spent six months there visiting the sacred sites and other monasteries, but returned to Cyprus still determined to live as a hermit.

In 1160, Neophytos found a cave in the Trodos Mountains just north of Paphos and began turning this into his hermitage by hand. When the Bishop of Paphos heard about it, he insisted that Neophytos accept consecration as a priest and also take on a disciple. Over time that one discipline turned into many, and an entire monastery grew at the foot of the cliff containing Neophytos’ cave/hermitage. A church was built and dedicated to the Holy Cross.

Although Neophytos had initially sought solitude, he was (he says) “forced” to interact not only with the monks of his monastery but with the many visitors who sought his advice. He read voraciously and was also an extremely prolific writer, producing numerous biographies of saints, interpreting scripture, composing hymns, codifying the rules of his monastery, and writing a (lost!) history of Cyprus. He also maintained a rigorous correspondence with people as far away as Constantinople. Last but not least, he commissioned the magnificent wall paints of his hermitage, which had grown into a nave, church and cell, which can still be admired to this day. He is believed to have died in 1214.

Both his writings and his letters demonstrate that far from being disinterested in the affairs of the world, Neophytos was actively concerned and, indeed, engaged in with current events―from his cell in the side of a mountain. In short, although he did not want to live with others in a community, he did care about what was happening beyond his cave. More: he recorded ― and at times tried to influence ― the course of events by the advice he offered his visitors and those with whom he corresponded.

There is considerable evidence that the educated and aristocratic elites disparaged Neophytos’ somewhat simple and direct style of writing, but this may have been the very reason he was so well loved by the common people of Cyprus: they could understand what he was talking/writing about better than the religious tracts of the traditional, erudite elite writing from distant Constantinople. It was above all the common people of Cyprus who saw in Neophytos a man of exceptional spiritual wisdom.

In the period covered by my novel, Neophytos was already a famous “holy man,” although he would not be sanctified until after his death. Furthermore, by the time the Lusignans came to Cyprus, Neophytos’ monastery had been in existence roughly 10 years. It is not, therefore, so far-fetched that a monk (such as my fictional Father Andronicus) would turn to Neophytos for advice and assistance. As a man with great influence, it likewise makes sense for Neophytos to play a mediating role between Orthodox rebels and Frankish invaders.

It was only after I had decided to include Neophytos in the novel that I saw the wonderful, additional opportunity to have Humphrey de Toron find sanctuary in Neophytos’ reclusive monastery. While it is recorded that Toron went to Cyprus with Guy, nothing is heard from him after that. Neither he nor his descendants appear in history as lords and vassals of the Lusignans. Furthermore, because he never recognized the annulment of his marriage to Isabella, Humphrey had challenged Isabella’s marriage to both Montferrat and Champagne. Yet he was conspicuously silent about her marriage to Aimery de Lusignan. This has led historians to assume he was dead by 1197, the year of this last marriage of Isabella. Another explanation, however, is that he had by then made peace with his fate and consciously chose to retire from the world. I liked that image and so included it in my novel.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

In contrast to the Latin and French chronicles (that in a sentence or two claim that the people of Cyprus welcomed Guy de Lusignan―after driving out the Templars―and every one lived happily ever after), Neophytos’ account suggests an extended period of oppression, resistance, violence and struggle. To be sure, Neophytos’ descriptions of all the twelfth century rulers of Cyprus are negative and his commentary on contemporary events is characterized by a pervasive sense of gloom and impending doom.

Yet the fact remains: he was living on Cyprus during the period described in the novel. As such he is the only eye-witness of events that we can still “hear from” today―and he describes the increasing lawlessness and deterioration of governance that is a major theme of my novel.

Furthermore, he was known to have traveled to the Kingdom of Jerusalem in his youth, giving him at least a little insight into what the Kingdom of Jerusalem was like. Most important, he received many visitors to his hermitage in the period of the novel. The temptation to have Balian meet him face to face was too great to resist!

The historical Neophytos was born to a peasant family in the Cypriot mountains in 1134. He, like his parents, was illiterate. At the age of 18 he caused a major scandal by running away to a monastery to avoid an arranged marriage. Because he was illiterate, he was initially assigned to tend the monastery vineyard, but after five years he had learned to read and write sufficiently to be made assistant sacristan. He performed these duties for two years, but then he expressed his desire to become a hermit. His superiors did not think he was ripe enough at the age of 25 for such a life, so instead sent him on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He spent six months there visiting the sacred sites and other monasteries, but returned to Cyprus still determined to live as a hermit.

In 1160, Neophytos found a cave in the Trodos Mountains just north of Paphos and began turning this into his hermitage by hand. When the Bishop of Paphos heard about it, he insisted that Neophytos accept consecration as a priest and also take on a disciple. Over time that one discipline turned into many, and an entire monastery grew at the foot of the cliff containing Neophytos’ cave/hermitage. A church was built and dedicated to the Holy Cross.

Although Neophytos had initially sought solitude, he was (he says) “forced” to interact not only with the monks of his monastery but with the many visitors who sought his advice. He read voraciously and was also an extremely prolific writer, producing numerous biographies of saints, interpreting scripture, composing hymns, codifying the rules of his monastery, and writing a (lost!) history of Cyprus. He also maintained a rigorous correspondence with people as far away as Constantinople. Last but not least, he commissioned the magnificent wall paints of his hermitage, which had grown into a nave, church and cell, which can still be admired to this day. He is believed to have died in 1214.

Both his writings and his letters demonstrate that far from being disinterested in the affairs of the world, Neophytos was actively concerned and, indeed, engaged in with current events―from his cell in the side of a mountain. In short, although he did not want to live with others in a community, he did care about what was happening beyond his cave. More: he recorded ― and at times tried to influence ― the course of events by the advice he offered his visitors and those with whom he corresponded.

There is considerable evidence that the educated and aristocratic elites disparaged Neophytos’ somewhat simple and direct style of writing, but this may have been the very reason he was so well loved by the common people of Cyprus: they could understand what he was talking/writing about better than the religious tracts of the traditional, erudite elite writing from distant Constantinople. It was above all the common people of Cyprus who saw in Neophytos a man of exceptional spiritual wisdom.

In the period covered by my novel, Neophytos was already a famous “holy man,” although he would not be sanctified until after his death. Furthermore, by the time the Lusignans came to Cyprus, Neophytos’ monastery had been in existence roughly 10 years. It is not, therefore, so far-fetched that a monk (such as my fictional Father Andronicus) would turn to Neophytos for advice and assistance. As a man with great influence, it likewise makes sense for Neophytos to play a mediating role between Orthodox rebels and Frankish invaders.

It was only after I had decided to include Neophytos in the novel that I saw the wonderful, additional opportunity to have Humphrey de Toron find sanctuary in Neophytos’ reclusive monastery. While it is recorded that Toron went to Cyprus with Guy, nothing is heard from him after that. Neither he nor his descendants appear in history as lords and vassals of the Lusignans. Furthermore, because he never recognized the annulment of his marriage to Isabella, Humphrey had challenged Isabella’s marriage to both Montferrat and Champagne. Yet he was conspicuously silent about her marriage to Aimery de Lusignan. This has led historians to assume he was dead by 1197, the year of this last marriage of Isabella. Another explanation, however, is that he had by then made peace with his fate and consciously chose to retire from the world. I liked that image and so included it in my novel.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on September 02, 2017 03:37

August 27, 2017

"Of Mothers, Queens and Daughters" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

The relations between mothers and daughters can be very turbulent even in the best of times. Imagine then the added complications when both women are queens?

An excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

“Mama!” Queen Isabella noticed her mother at last. “What brings you to Acre? When you left after Christmas Uncle Balian” (as a child Isabella had picked up the habit of referring to her stepfather as “Uncle Balian”) “said he didn’t expect to be back until after the sowing was finished.”

“True. We didn’t expect an emergency.”

“Emergency? What’s happened? Have the rains caused flooding—”

Maria Zoë was shaking her head, “No, no. Shall we sit outside in the fresh air?” She indicated the courtyard bathed in morning sunshine.

Isabella slipped her arm through her mother’s, and together they went out into the little courtyard. The sun was pouring in and the surrounding buildings protected it from the wind. They sat down on a plaster bench built against the wall, and Isabella looked expectantly at her mother. “Tell me! What is it?”

“Actually, you must already know,” Maria Zoë started cautiously. Her relationship with Isabella was close, but it had also been stormy at times. There had been tense periods when Isabella had been rebellious and aggressive. “Your brother John rode all night to reach us.”

“Oh!” Isabella gasped and drew back slightly, her face flushing. “You mean Aimery’s arrest? Henri had to!” She defended her husband at once. “He can’t risk him plotting against us for another hour! He promised me he would not put him chains or anything like that, but he had to ensure Aimery could not communicate with his brother or the Pisans!”

Maria Zoë was relieved to hear that Isabella had at least extracted a promise of good treatment; that alone would mean a great deal to Eschiva. More important, it suggested that her daughter was not entirely indifferent to her best friend’s husband. To her daughter she asked simply, “What is this all about, Isabella? You’ve known Aimery all your life. You know he’s sacrificed the better part of his life for Jerusalem. How can you think he might have turned traitor now?”

“He’s a Lusignan, Mama! And you know his brother has never stopped claiming the crown of Jerusalem. Guy did everything he could to prevent me obtaining what was rightfully mine. He even talked Humphrey into telling me I had no claim as long as he lived. And don’t you remember how he tried to ingratiate himself with the Dowager Queen of Sicily, hoping to marry her? He’s still looking for a new wife. If he marries again and has children, he will claim Jerusalem for them!” Isabella hardly stopped for breath as she fervently delivered this monologue.

Maria Zoë knew her daughter’s passionate nature, and nodded before countering in a reasonable tone, “I don’t doubt a word you’re saying, Bella. Guy has been an intriguer, a seducer, and arrogantly blind to his own faults for as long as I’ve known him—which is more than a decade. But Aimery is not Guy—any more than you are Sibylla.”

Isabella had always hated her older half-sister Sibylla, so the argument made her catch her breath and start biting her lower lip. Maria Zoë pressed her point. “I know Aimery backed Guy’s usurpation six years ago, but he has lived to regret that a thousand times over. He’s told me that himself, he’s told your stepfather, and he’s told your brother the same thing. I honestly do not think that he could be involved in any kind of plot against you or Henri, even if—as has not yet be proved—his brother is behind the Pisan pirates preying on our shipping.”

Isabella was frowning and biting her lip in distress. “You’re probably right, Mama. I want to believe you, for Eschiva’s sake if nothing more, but arresting him was a precaution Henri had to take. If he’s innocent, then I’m sure Henri will release him.”

Maria Zoë took a deep breath and concluded this was probably the most she could hope to gain at the moment. Pressing Isabella too hard could easily trigger an angry rejection of “interference.” It would have been easier to back off, however, if she hadn’t spent the night with Eschiva and her children. Eschiva, usually so calm and self-possessed, had broken down and cried in Maria Zoё’s arms. Eschiva had lived with Maria Zoë and Balian as a child, and the ties had never weakened. Maria Zoë loved Eschiva like one of her own daughters, and she knew how much Eschiva had suffered over the years―from Aimery’s infidelities in his youth, from his captivity after Hattin and his absence at the siege of Acre, and more recently from the uncertainties of this last military campaign under the King of England. She and Aimery had only just started to rebuild their lives―and now this.

“That’s really the best I can promise,” Isabella spoke into Maria Zoë’s thoughts, sounding faintly defiant already.

“I know, Bella,” Maria Zoë chose tactical retreat. “That’s all I ask.” She smiled and kissed her firstborn on the forehead and then stood. “I must get back to Eschiva. She’s understandably very distraught and frightened.”

“You must assure her that no matter what comes to light about Aimery, she will always be a sister to me. I promise she’ll never be made to suffer, even if Aimery is found to be a traitor.”

“Ah, but sweetheart, if anything happens to Aimery she will suffer, because she loves him—not as you love Henri, nor indeed as I love your stepfather, but as a woman who has known no other husband since she was eight years old. Aimery is her life, Bella. If you take Aimery away, Eschiva will simply die.” Maria Zoë patted her daughter’s shoulder as if comforting her―but judging by Isabella’s stricken face, her message had gone home.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on August 27, 2017 01:00

The Last Crusader Kingdom: "Of Mothers, Queens and Daughters" - Excerpt 2

The Last Crusader Kingdom

"Of Mothers, Queens and Daughters"An Excerpt “Mama!” Queen Isabella noticed her mother at last. “What brings you to Acre? When you left after Christmas Uncle Balian” (as a child Isabella had picked up the habit of referring to her stepfather as “Uncle Balian”) “said he didn’t expect to be back until after the sowing was finished.”

"Of Mothers, Queens and Daughters"An Excerpt “Mama!” Queen Isabella noticed her mother at last. “What brings you to Acre? When you left after Christmas Uncle Balian” (as a child Isabella had picked up the habit of referring to her stepfather as “Uncle Balian”) “said he didn’t expect to be back until after the sowing was finished.” “True. We didn’t expect an emergency.”

“Emergency? What’s happened? Have the rains caused flooding—”

Maria Zoë was shaking her head, “No, no. Shall we sit outside in the fresh air?” She indicated the courtyard bathed in morning sunshine.

Isabella slipped her arm through her mother’s, and together they went out into the little courtyard. The sun was pouring in and the surrounding buildings protected it from the wind. They sat down on a plaster bench built against the wall, and Isabella looked expectantly at her mother. “Tell me! What is it?”

“Actually, you must already know,” Maria Zoë started cautiously. Her relationship with Isabella was close, but it had also been stormy at times. There had been tense periods when Isabella had been rebellious and aggressive. “Your brother John rode all night to reach us.”

“Oh!” Isabella gasped and drew back slightly, her face flushing. “You mean Aimery’s arrest? Henri had to!” She defended her husband at once. “He can’t risk him plotting against us for another hour! He promised me he would not put him chains or anything like that, but he had to ensure Aimery could not communicate with his brother or the Pisans!”

Maria Zoë was relieved to hear that Isabella had at least extracted a promise of good treatment; that alone would mean a great deal to Eschiva. More important, it suggested that her daughter was not entirely indifferent to her best friend’s husband. To her daughter she asked simply, “What is this all about, Isabella? You’ve known Aimery all your life. You know he’s sacrificed the better part of his life for Jerusalem. How can you think he might have turned traitor now?”

“He’s a Lusignan, Mama! And you know his brother has never stopped claiming the crown of Jerusalem. Guy did everything he could to prevent me obtaining what was rightfully mine. He even talked Humphrey into telling me I had no claim as long as he lived. And don’t you remember how he tried to ingratiate himself with the Dowager Queen of Sicily, hoping to marry her? He’s still looking for a new wife. If he marries again and has children, he will claim Jerusalem for them!” Isabella hardly stopped for breath as she fervently delivered this monologue.

Maria Zoë knew her daughter’s passionate nature, and nodded before countering in a reasonable tone, “I don’t doubt a word you’re saying, Bella. Guy has been an intriguer, a seducer, and arrogantly blind to his own faults for as long as I’ve known him—which is more than a decade. But Aimery is not Guy—any more than you are Sibylla.”

Isabella had always hated her older half-sister Sibylla, so the argument made her catch her breath and start biting her lower lip. Maria Zoë pressed her point. “I know Aimery backed Guy’s usurpation six years ago, but he has lived to regret that a thousand times over. He’s told me that himself, he’s told your stepfather, and he’s told your brother the same thing. I honestly do not think that he could be involved in any kind of plot against you or Henri, even if—as has not yet be proved—his brother is behind the Pisan pirates preying on our shipping.”

Isabella was frowning and biting her lip in distress. “You’re probably right, Mama. I want to believe you, for Eschiva’s sake if nothing more, but arresting him was a precaution Henri had to take. If he’s innocent, then I’m sure Henri will release him.”

Maria Zoë took a deep breath and concluded this was probably the most she could hope to gain at the moment. Pressing Isabella too hard could easily trigger an angry rejection of “interference.” It would have been easier to back off, however, if she hadn’t spent the night with Eschiva and her children. Eschiva, usually so calm and self-possessed, had broken down and cried in Maria Zoё’s arms. Eschiva had lived with Maria Zoë and Balian as a child, and the ties had never weakened. Maria Zoë loved Eschiva like one of her own daughters, and she knew how much Eschiva had suffered over the years―from Aimery’s infidelities in his youth, from his captivity after Hattin and his absence at the siege of Acre, and more recently from the uncertainties of this last military campaign under the King of England. She and Aimery had only just started to rebuild their lives―and now this.

“That’s really the best I can promise,” Isabella spoke into Maria Zoë’s thoughts, sounding faintly defiant already.

“I know, Bella,” Maria Zoë chose tactical retreat. “That’s all I ask.” She smiled and kissed her firstborn on the forehead and then stood. “I must get back to Eschiva. She’s understandably very distraught and frightened.”

“You must assure her that no matter what comes to light about Aimery, she will always be a sister to me. I promise she’ll never be made to suffer, even if Aimery is found to be a traitor.”

“Ah, but sweetheart, if anything happens to Aimery she will suffer, because she loves him—not as you love Henri, nor indeed as I love your stepfather, but as a woman who has known no other husband since she was eight years old. Aimery is her life, Bella. If you take Aimery away, Eschiva will simply die.” Maria Zoë patted her daughter’s shoulder as if comforting her―but judging by Isabella’s stricken face, her message had gone home.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on August 27, 2017 01:00

August 20, 2017

Characters in The Last Crusader Kingdom: Leo of Armenia

Although most of the plot in "The Last Crusader Kingdom" is speculation based on earlier or later developments, one of the most bizarre incidents described, the capture of Eschiva d’Ibelin by pirates, is recorded in the chronicles. While little beyond the name of the pirate (Kanakes/Canaqui) is known, the positive role played by Leo of Armenia gave me an excuse to introduce this fascinating man into the novel ― even if only briefly.

Leo (also Levon) was an Armenian prince who successfully defended and expanded his territories, gained a crown, and through his pro-Latin policies opened Armenia up to increased trade with the Italian city-states, thereby greatly increasing its prosperity.

He was born in 1150, the younger son of Stephan, the son of Leo I, Lord of Armenian Cilicia. When just fifteen his father was murdered, apparently by agents of Leo’s paternal uncle, who whereupon made himself lord of Cilicia, while Leo and his elder brother Rupin sought refuge with their maternal relatives.

Another assassination, this time of the man who had killed their father, brought Rupin to the throne, with Leo, now 25, acting as his loyal and able lieutenant. In 1183, however, Rupin was taken prisoner by Bohemond III of Antioch. With his brother in captivity, Leo assumed control of Cilicia and set about raising the huge ransom demanded. Four years later, when Rupin returned, he chose (whether voluntarily or not is unclear) to retire to a monastery rather than resume the rule of his principality. Leo became the ruler of Cilicia.

It was, however, now 1187 and the powerful Sultan of Syria and Egypt, Salah ad-Din, had just made an alliance with the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelus. Leo concluded a treaty of expediency with Antioch, acknowledging Antioch’s suzerainty over Cilicia, and then took the offensive against the Seljuk Turks successfully. He also supported the Third Crusade, both by first providing men and supplies to Friedrich Barbarossa and, later, troops for the siege of Acre. He also loaned money to Bohemond of Antioch, although the latter supposedly did not repay it.

In 1191, when Salah ad-Din withdrew from the formerly Templar castle of Baghras, Leo sent troops to seize control of this vital fortress. This brought him into renewed conflict with Bohemond of Antioch, who considered the castle part of his principality. Leo invited Bohemend to Baghras to discuss the situation and promptly took him and his wife hostage. The tables reversed from the situation after his brother’s capture, Leo demanded that Antioch acknowledge Armenian suzerainty over Antioch.

Bohemond quickly caved in and sent orders for the surrender of Antioch to Leo’s troops. The citizens of Antioch, however, were not prepared to surrender. A riot ensued that overwhelmed the Armenian troops. Bohemond’s eldest son Raymond seized control and was installed as regent until his father’s release could be secured. Raymond of Antioch also appealed to the King of Jerusalem, Henri de Champagne, for assistance. Henri duely undertook a diplomatic mission to Sis, Leo’s capital. In exchange for renouncing his claim to suzerainty over Armenia, Bohemend, his wife and entourage were released without further ransom payments.

At about the same time (the dates are very vague in the contemporary chronicles), Leo obtained a crown. He appealed to the Holy Roman Emperor, the Byzantine Emperor and the Pope, winning the support of the later by promising to submit the Armenian church to Rome. Although it is doubtful if this was anything more than a ploy, it was sufficient to win Leo a crown. Just like Aimery de Lusignan, he was crowned and anointed by the Imperial Chancellor of Henry VI Hohenstaufen and the Papal Legate, the Bishop of Mainz, in January 1198. Leo reigned until 1219, and much of his later life he was involved in a struggle to impose his great-nephew as Prince of Antioch, but that is long after the events described in The Last Crusader Kingdom and so beyond the scope of this post.

What intrigued me about Leo beyond the fact that he played a positive role in securing the release of Eschiva d’Ibelin is the tantalizing possibility that he had known Eschiva’s father, Baldwin d’Ibelin.

Baldwin d’Ibelin, Balian’s elder brother, disappears from the history of the Holy Land in 1186, after dramatically refusing to do homage to Guy de Lusignan. He then renounced his titles and wealth in favor of his son and quit the kingdom. The Lyon Continuation of William of Tyre, presumably based on the lost account of the Ibelin squire Ernoul, describes it this way:

After this [Guy de Lusignan] summoned Baldwin d’Ibelin and the other barons to a parliament at Acre…He requested that they pay him homage and fealty as vassals should to their lord… [He] summoned [Baldwin d’Ibelin] three times. But he, being a wise and stalwart man…replied: “My father never did homage to yours, and I will not do it to you…I will quit your kingdom within three days."

Then he took leave of Balian his brother and entrusted his son to him to look after until he reached his majority. After that he got on the road and, setting off with the other knights who had commended their fiefs, went to the Prince of Antioch. When the prince of Antioch heard that Baldwin of Ibelin and so many knights were coming, he was delighted. He went out to meet them and received them with great joy. (Peter Edbury, The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade: Sources in Translation, Ashgate, 1998, p. 28-29. The Old French Continuation of William of Tyre, paragraph 21.)

And he is never heard from again.

To be sure, the chronicle sited above talks about the barons advising King Guy to send to Baldwin of Ibelin and the Prince of Antioch to come to the kingdom’s aid when Saladin invaded, but clearly neither of them did. The Prince of Antioch was soon fighting for his own survival, but we hear no mention of Baldwin d’Ibelin being at his side.

However, the chronicle tells us the following:

When Leo of the Mountain, who was lord of Armenia, came to hear of the outrage that had befallen King Aimery and his lady, he was deeply saddened because of the love that he had both for King Aimery who was his friend and for Baldwin of Ibelin whose daughter she had been.

But how, where and when had Leo of Armenia come to know Baldwin d’Ibelin?

There is no chance that Baldwin and Leo would have met prior to Baldwin’s self-imposed exile from the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1186. Thus, they could only have come to know and like one another after Baldwin left the Kingdom of Jerusalem, most likely during the short period of truce between Antioch and Armenia, 1187-1193. This was precisely the period in which Leo of Armenia was doing all he could to hold back the Seljuk Turks on one hand, and assist the crusaders and fellow Christian states in the East on the other.

Conceivably, Baldwin d’Ibelin escorted Leo’s brother Rupin back to Armenia after Rupin’s ransom was paid. As this coincided roughly with the Battle of Hattin, Baldwin’s absence in Armenia would explain why he did not follow any appeals sent him, presumably by his brother or former peers, to aid in the defense of his former kingdom.

If Baldwin was in Armenia when news of Hattin arrived, he might also have concluded that all was lost in Jerusalem (as he had allegedly predicted), and have offered his sword to Leo. Leo was about to undertake a daring strike with inferior forces against the Seljuks. And if Baldwin d’Ibelin fought with Leo in the years of his greatest peril, to die sometime thereafter, possibly in battle or of his wounds, it would explain why Leo of Armenia responded so vigorously when he learned of Eschiva’s kidnapping.

While this is mere speculation ― as with so much of The Last Crusader Kingdom ― it is not mere fantasy. For Eschiva, I believe, it would have been a comfort to learn that her father had, after abandoning her in 1187, come to her aid from beyond the grave by bringing her the assistance of this remarkable prince in her hour of greatest need.

Buy Now!

Buy Now! For more about Baldwin d'Ibelin see the Jerusalem Trilogy:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on August 20, 2017 00:10

August 12, 2017

"Arrest for High Treason" - An Excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom"

Aimery de Lusignan was appointed Constable of Jerusalem by Baldwin IV in the late 1170s and retained that position until, abruptly, in 1193, he was arrested for High Treason by Henri de Champagne, consort of Queen Isabella -- the uncrowned King of Jerusalem 1192-1197. An excerpt from "The Last Crusader Kingdom."

The men who forced their way inside were dressed in chain mail from head to toe. They wore skullcap helmets with heavy nose guards. Most terrifying of all, they wore surcoats with the arms of Jerusalem on them: they were the King’s men.

“Where’s Lord Aimery?” one of them barked at the stunned servants.

“I’m here!” Aimery called from the floor above. Without hesitation the four armored men pushed past the frightened servants to the stairs at the back of the vaulted room. They pounded up to the next floor, and as they emerged out of the stairway, they found the Constable of Jerusalem hastily donning his surcoat while a young squire held his sword ready for him to take.

“Hold that, boy!” one of the King’s men shouted, springing to put himself between the squire and the Constable. He pushed the squire backwards, pinned him against the wall, and wrenched the sword out of his hands with little trouble.

Meanwhile, the sergeant turned his attention to the Constable himself. “My lord, you are under arrest for high treason! Either you come with us willingly, or we have orders to take you by force.”

Aimery de Lusignan was a handsome man in his early fifties. His shoulder-length blond hair was somewhat disheveled and his face was sprouting the beginnings of a beard, but he had managed to pull on braies, hose, and a gambeson over his nightshirt. He stood with his shoulders squared and his head held high. “The charges are false and slanderous!” he told the sergeant firmly. “I will defend myself before the High Court.”

“Maybe. For now you’re coming with us!” the sergeant answered bluntly, ominously lowering his hand to his hilt.

“Where are you taking me?” the Constable asked gruffly.

“To the royal dungeon, where all traitors are held! Now, are you coming willingly, or must I use force?”

“Will you at least allow me to put on boots?” the Constable asked back in a voice edged with bitterness.

“No tricks!” the sergeant warned, drawing his sword for emphasis before nodding to Lord Aimery to get on with it.

The Constable walked across the room to where his knee-high boots were standing, the soft upper parts flopped over on their sides. He took the suede boots, sat on the nearest chest, and pulled them on one at a time. Then he stood and surveyed the room briefly; whether he was looking for a chance to escape or simply taking a last leave was unclear. The king’s men blocked the door, their swords drawn. They not only ensured he was trapped, they also kept his wife out. He could hear her anxious voice in the hall demanding an explanation. His squire was still pinned against the far wall, his eyes wide with shock and disbelief.

“John, get word to your father of what has happened,” the Constable ordered the youth before walking briskly toward the men sent to arrest him. He allowed them to close around him as he passed out of the door. They clattered down the stairs and out into the street, leaving John and Lady Eschiva standing on the upstairs landing in horrified paralysis.

“Treason?” Lady Eschiva asked the squire. “Did I hear correctly? Champagne has arrested my lord husband for treason? But that’s not possible!” she protested.

The Last Crusader Kingdom is now available on B&N and amazon.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

The men who forced their way inside were dressed in chain mail from head to toe. They wore skullcap helmets with heavy nose guards. Most terrifying of all, they wore surcoats with the arms of Jerusalem on them: they were the King’s men.

“Where’s Lord Aimery?” one of them barked at the stunned servants.

“I’m here!” Aimery called from the floor above. Without hesitation the four armored men pushed past the frightened servants to the stairs at the back of the vaulted room. They pounded up to the next floor, and as they emerged out of the stairway, they found the Constable of Jerusalem hastily donning his surcoat while a young squire held his sword ready for him to take.

“Hold that, boy!” one of the King’s men shouted, springing to put himself between the squire and the Constable. He pushed the squire backwards, pinned him against the wall, and wrenched the sword out of his hands with little trouble.

Meanwhile, the sergeant turned his attention to the Constable himself. “My lord, you are under arrest for high treason! Either you come with us willingly, or we have orders to take you by force.”

Aimery de Lusignan was a handsome man in his early fifties. His shoulder-length blond hair was somewhat disheveled and his face was sprouting the beginnings of a beard, but he had managed to pull on braies, hose, and a gambeson over his nightshirt. He stood with his shoulders squared and his head held high. “The charges are false and slanderous!” he told the sergeant firmly. “I will defend myself before the High Court.”

“Maybe. For now you’re coming with us!” the sergeant answered bluntly, ominously lowering his hand to his hilt.

“Where are you taking me?” the Constable asked gruffly.

“To the royal dungeon, where all traitors are held! Now, are you coming willingly, or must I use force?”

“Will you at least allow me to put on boots?” the Constable asked back in a voice edged with bitterness.

“No tricks!” the sergeant warned, drawing his sword for emphasis before nodding to Lord Aimery to get on with it.

The Constable walked across the room to where his knee-high boots were standing, the soft upper parts flopped over on their sides. He took the suede boots, sat on the nearest chest, and pulled them on one at a time. Then he stood and surveyed the room briefly; whether he was looking for a chance to escape or simply taking a last leave was unclear. The king’s men blocked the door, their swords drawn. They not only ensured he was trapped, they also kept his wife out. He could hear her anxious voice in the hall demanding an explanation. His squire was still pinned against the far wall, his eyes wide with shock and disbelief.

“John, get word to your father of what has happened,” the Constable ordered the youth before walking briskly toward the men sent to arrest him. He allowed them to close around him as he passed out of the door. They clattered down the stairs and out into the street, leaving John and Lady Eschiva standing on the upstairs landing in horrified paralysis.

“Treason?” Lady Eschiva asked the squire. “Did I hear correctly? Champagne has arrested my lord husband for treason? But that’s not possible!” she protested.

The Last Crusader Kingdom is now available on B&N and amazon.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on August 12, 2017 23:28

The Last Crusader Kingdom: "Arrest for High Treason" - An Excerpt

The Last Crusader Kingdom

"Arrest for High Treason!"

An Excerpt

The men who forced their way inside were dressed in chain mail from head to toe. They wore skullcap helmets with heavy nose guards. Most terrifying of all, they wore surcoats with the arms of Jerusalem on them: they were the King’s men.

“Where’s Lord Aimery?” one of them barked at the stunned servants.

“I’m here!” Aimery called from the floor above. Without hesitation the four armored men pushed past the frightened servants to the stairs at the back of the vaulted room. They pounded up to the next floor, and as they emerged out of the stairway, they found the Constable of Jerusalem hastily donning his surcoat while a young squire held his sword ready for him to take.

“Hold that, boy!” one of the King’s men shouted, springing to put himself between the squire and the Constable. He pushed the squire backwards, pinned him against the wall, and wrenched the sword out of his hands with little trouble.

Meanwhile, the sergeant turned his attention to the Constable himself. “My lord, you are under arrest for high treason! Either you come with us willingly, or we have orders to take you by force.”

Aimery de Lusignan was a handsome man in his early fifties. His shoulder-length blond hair was somewhat disheveled and his face was sprouting the beginnings of a beard, but he had managed to pull on braies, hose, and a gambeson over his nightshirt. He stood with his shoulders squared and his head held high. “The charges are false and slanderous!” he told the sergeant firmly. “I will defend myself before the High Court.”

“Maybe. For now you’re coming with us!” the sergeant answered bluntly, ominously lowering his hand to his hilt.

“Where are you taking me?” the Constable asked gruffly.

“To the royal dungeon, where all traitors are held! Now, are you coming willingly, or must I use force?”

“Will you at least allow me to put on boots?” the Constable asked back in a voice edged with bitterness.

“No tricks!” the sergeant warned, drawing his sword for emphasis before nodding to Lord Aimery to get on with it.

The Constable walked across the room to where his knee-high boots were standing, the soft upper parts flopped over on their sides. He took the suede boots, sat on the nearest chest, and pulled them on one at a time. Then he stood and surveyed the room briefly; whether he was looking for a chance to escape or simply taking a last leave was unclear. The king’s men blocked the door, their swords drawn. They not only ensured he was trapped, they also kept his wife out. He could hear her anxious voice in the hall demanding an explanation. His squire was still pinned against the far wall, his eyes wide with shock and disbelief.

“John, get word to your father of what has happened,” the Constable ordered the youth before walking briskly toward the men sent to arrest him. He allowed them to close around him as he passed out of the door. They clattered down the stairs and out into the street, leaving John and Lady Eschiva standing on the upstairs landing in horrified paralysis.

“Treason?” Lady Eschiva asked the squire. “Did I hear correctly? Champagne has arrested my lord husband for treason? But that’s not possible!” she protested.

The Last Crusader Kingdom is due to be released soon.

Watch for it on amazon or Barnes and Noble.

Watch for it on amazon or Barnes and Noble.

"Arrest for High Treason!"

An Excerpt

The men who forced their way inside were dressed in chain mail from head to toe. They wore skullcap helmets with heavy nose guards. Most terrifying of all, they wore surcoats with the arms of Jerusalem on them: they were the King’s men.

“Where’s Lord Aimery?” one of them barked at the stunned servants.

“I’m here!” Aimery called from the floor above. Without hesitation the four armored men pushed past the frightened servants to the stairs at the back of the vaulted room. They pounded up to the next floor, and as they emerged out of the stairway, they found the Constable of Jerusalem hastily donning his surcoat while a young squire held his sword ready for him to take.

“Hold that, boy!” one of the King’s men shouted, springing to put himself between the squire and the Constable. He pushed the squire backwards, pinned him against the wall, and wrenched the sword out of his hands with little trouble.

Meanwhile, the sergeant turned his attention to the Constable himself. “My lord, you are under arrest for high treason! Either you come with us willingly, or we have orders to take you by force.”

Aimery de Lusignan was a handsome man in his early fifties. His shoulder-length blond hair was somewhat disheveled and his face was sprouting the beginnings of a beard, but he had managed to pull on braies, hose, and a gambeson over his nightshirt. He stood with his shoulders squared and his head held high. “The charges are false and slanderous!” he told the sergeant firmly. “I will defend myself before the High Court.”

“Maybe. For now you’re coming with us!” the sergeant answered bluntly, ominously lowering his hand to his hilt.

“Where are you taking me?” the Constable asked gruffly.

“To the royal dungeon, where all traitors are held! Now, are you coming willingly, or must I use force?”

“Will you at least allow me to put on boots?” the Constable asked back in a voice edged with bitterness.

“No tricks!” the sergeant warned, drawing his sword for emphasis before nodding to Lord Aimery to get on with it.

The Constable walked across the room to where his knee-high boots were standing, the soft upper parts flopped over on their sides. He took the suede boots, sat on the nearest chest, and pulled them on one at a time. Then he stood and surveyed the room briefly; whether he was looking for a chance to escape or simply taking a last leave was unclear. The king’s men blocked the door, their swords drawn. They not only ensured he was trapped, they also kept his wife out. He could hear her anxious voice in the hall demanding an explanation. His squire was still pinned against the far wall, his eyes wide with shock and disbelief.

“John, get word to your father of what has happened,” the Constable ordered the youth before walking briskly toward the men sent to arrest him. He allowed them to close around him as he passed out of the door. They clattered down the stairs and out into the street, leaving John and Lady Eschiva standing on the upstairs landing in horrified paralysis.

“Treason?” Lady Eschiva asked the squire. “Did I hear correctly? Champagne has arrested my lord husband for treason? But that’s not possible!” she protested.

The Last Crusader Kingdom is due to be released soon.

Watch for it on amazon or Barnes and Noble.

Watch for it on amazon or Barnes and Noble.

Published on August 12, 2017 23:28

August 5, 2017

Characters in The Last Crusader Kingdom: John d’Ibelin

Many of the characters in The Last Crusader Kingdom are familiar to readers of this blog from the Jerusalem Trilogy: Balian d’Ibelin, Maria Comnena, Guy and Aimery de Lusignan, Eschiva d’Ibelin-Lusignan, Isabella of Jerusalem and Henri de Champagne. I have provided short biographies of all of them and discussed writing about them in earlier entries. But there are a few characters in this novel that played only a minor role in the Jerusalem Trilogy, or did not feature at all. Over the next weeks I will be introducing these characters, starting with the historical figures, followed by the fictional characters.

The most important “new” character in The Last Crusader Kingdom is John d’Ibelin.

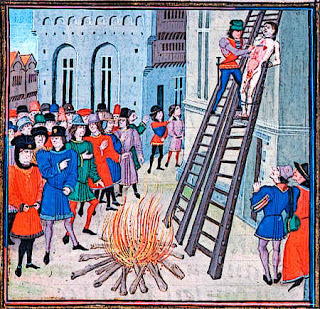

The Seal of John d'Ibelin

The Seal of John d'Ibelin

John was the eldest son of Balian d’Ibelin and the Byzantine princess Maria Comnena, and he was to play a dramatic and important role in the history of the Kingdoms of Jerusalem and Cyprus between 1205 and his death in 1236. Unfortunately, however, little is known about his early life, and nothing whatever is known about the period of his life described in this novel.

John was probably born in 1179, and was presumably a child of eight when the Battle of Hattin destroyed the world into which he had been born. He was certainly in Jerusalem when father came to the city to rescue his family―only to remain in the city and organize the defense. John, along with his siblings and his mother, however, was escorted from the apparently doomed city by Saladin’s own body-guard in a profoundly generous gesture on the part of the Sultan before the siege .

The next time John is mentioned in the historical record is in 1198, when he is named Constable of Jerusalem by King Aimery de Lusignan. He would have been only 19 at the time, and historians, balking at the idea of such a young man being capable of fulfilling the duties of Constable, hypothesize that the appointment was nominal, a means of providing for him materially. Yet, as his father’s eldest son, he would have already inherited the barony of Caymont, if (as historians assume) his father was already dead. Furthermore, historians appear to overlook the fact that young noblemen and kings came of age at 15 in the Holy Land, so a noblemen of 19 would have been young but not viewed as immature. If kings could command at 15, why shouldn’t a constable at 19? Last but not least, John witnessed all existing charters of King Aimery, suggesting a close relationship between the two men.

John was still quite young, 24, when he was named Regent of Jerusalem first for his half-sister Isabella following the death of her fourth husband, King Aimery, and then for his niece, Isabella's eldest daughter and heir, Maria de Montferrat, after Isabella’s death a few months later. As regent he arranged a marriage between his niece Alice of Champagne (Isabella’s daughter by her third husband, Henri de Champagne) with the heir to the Cypriot throne, Hugh de Lusignan. In addition, he was influential in the marriage of Maria de Montferrat with John de Brienne. Meanwhile, sometime between 1198 and 1205, he had traded the constableship for the lordship of Beirut, and it was as Lord of Beirut that he has gone down into history.

John was still quite young, 24, when he was named Regent of Jerusalem first for his half-sister Isabella following the death of her fourth husband, King Aimery, and then for his niece, Isabella's eldest daughter and heir, Maria de Montferrat, after Isabella’s death a few months later. As regent he arranged a marriage between his niece Alice of Champagne (Isabella’s daughter by her third husband, Henri de Champagne) with the heir to the Cypriot throne, Hugh de Lusignan. In addition, he was influential in the marriage of Maria de Montferrat with John de Brienne. Meanwhile, sometime between 1198 and 1205, he had traded the constableship for the lordship of Beirut, and it was as Lord of Beirut that he has gone down into history.

Beirut was retaken for Christendom by German crusaders in 1198, but was so badly destroyed in the process (either by the retreating Saracens or the advancing Germans or both) that it was allegedly an uninhabitable ruin. Despite that, it was an immensely valuable prize because of its harbor, the fertile surrounding coastal territory, and the proximity to Antioch. It was clearly a mark of great favor and trust that John d'Ibelin was granted the lordship of Beirut ― even if it meant giving up the constableship.

John d’Ibelin resettled the city and rebuilt the fortifications. He also built a palace that won the admiration of visitors for its elegance and luxury. It included polychrome marble walls, frescoes, painted ceilings, fountains, gardens, and large, glazed windows offering splendid views to the sea.

The Mediterranean Coast of the Levant

The Mediterranean Coast of the Levant

John first married (presumably in 1198 or 1199) a certain Helvis of Nephin, about whom nothing is known beyond that she delivered to him five sons, all of whom died as infants. Helvis herself died before 1207, when John married the widowed heiress of Arsur, Melisende. By Melisende, John had another five sons and a single daughter.

In 1210, Maria de Montferrat came of age, married John de Brienne, and the couple were crowned Queen and King of Jerusalem; John’s regency was over. Furthermore, he completely disappeared from the witness lists of the kingdom, suggesting he had withdrawn to Beirut rather than remaining in attendance on the new king and queen―whether voluntarily, or after some dispute is unknown.

While nothing is known for sure about John’s whereabouts between 1210 and 1217, by the latter date John and his younger brother Philip headed the list of witness to all existing charters of King Hugh I of Cyprus. This suggests that at some unknown point before 1217 he had acquired important fiefs on Cyprus. In 1227, he was named regent for the orphaned heir to the Cypriot crown, Henry I.

Only a year later, however, the Holy Roman Emperor, Friedrich II Hohenstaufen arrived at the head of the Fifth crusade, and John immediately found himself on a collision course. The events are far too complex for this short essay (but will be revisited later!), but resulted in John leading a rebellion against the Emperor and his appointed lieutenants that lasted sporadically from 1229 – 1232. At stake was the constitution of the Kingdoms of Jerusalem and Cyprus, with John defending the traditional pre-eminent role of the High Court against the Holy Roman Emperor's attempt to impose absolute monarchy on both kingdoms. The Hohenstaufen suffered a complete defeat, eventually losing his suzerainty over Cyprus altogether, and never able to exercise his royal authority throughout the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

John has been accused by historians of defending only the parochial interests of his family and the leading baronial families. Certainly, his stance undermined central authority in the Kingdom of Jerusalem that ultimately weakened it. Against this argument stands the fact that his rebellion actually strengthened the position of the Kings of Cyprus, and the simple fact that Friedrich II’s heavy handed attempts to disinherit men without due process and run rough-shod over local laws and customs meant John was fighting as much for the rule of law as for personal interests.

The fact that John was strongly supported by the commons of Acre further underlines the fact that he was not solely self-interested. John had no problem accepting the authority of John de Brienne and Henri de Lusignan, after all. I believe, therefore, a strong case can be made for John opposing not the conceptof central authority but rather the individual― Friedrich II, who even his admirers describe as arrogant and authoritarian. Friedrich II believed that, like a Roman Emperor, he was God’s representative on earth. Friedrich II provoked revolts in the West as well as the East, and was excommunicated several times.

But all this is grist for future blog posts when I come to write about the baronial revolt against Friedrich II in future novels.