Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 40

July 29, 2017

The Ibelins on Cyprus and the Role of a Byzantine Princess

Last week I explained why I challenged the common myth about the peaceful reception of Guy de Lusignan on Cyprus. There is, however, another “mystery” which I seek to explain in The Last Crusader Kingdom, namely, the roots of the Ibelin influence on Cyprus.

Historians such as Edbury posit that the Ibelins were inveterate opponents of the Lusignans until the early 13th century. They note that there is no record of Ibelins setting foot on the island of Cyprus before 1210 and insist that it is “certain” they were not among the early settlers―while admitting that it is impossible to draw up a complete list of the early settlers. Edbury, furthermore, admits that “it is not possible to trace [the Ibelin’s] rise in detail” yet argues it was based on close ties to King Hugh I. Close? Hugh was the son of a cousin, which in my opinion is not terribly “close” kinship.

Even more difficult to understand in the conventional version of events is that the Ibelins became so powerful and entrenched that within just seven years (1217) of their supposed “first appearance” on Cyprus an Ibelin was appointed regent of Cyprus, presumably with the consent of the Cypriot High Court--that is the barons and bishops of the island who had supposedly been on the island far longer and over the heads of King's first cousin. I don’t think that’s credible.

My thesis and the basis of this novel is that while the Ibelins (that is, Baldwin and Balian d’Ibelin) were inveterate opponents of Guy de Lusignan, they were on friendly terms with Aimery de Lusignan. Aimery was, for a start, married to Baldwin’s daughter, Eschiva. We have references, furthermore, to them “supporting” Aimery as late as Saladin’s invasion of 1183. I think the Ibelins were very capable of distinguishing between the two Lusignan brothers, and judging Aimery for his own strengths rather than condemning him for his brother’s weaknesses.

Furthermore, the conventional argument that Balian d’Ibelin died in late 1193 because he disappears from the charters of the Kingdom of Jerusalem at that date is reasonable -- but not compelling. The fact that Balian d’Ibelin disappears from the records of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1193 may mean that he died, but it could just as easily mean that he was occupied elsewhere. The Ibelin brothers of the next generation, John and Philip, "disappear" from the records of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1217 too, but they were very much alive, active and powerful -- one in Beirut and the other apparently on Cyprus.

Balian's disappearance from the records of Jerusalem could also have been because he busy on Cyprus. The lack of documentary proof for his presence on Cyprus is not grounds for dismissing the possibility of his presence there because 1) the Kingdom of Cyprus did not yet exist so there was no chancery and no elaborate system for keeping records, writs and charters etc., and 2) those who would soon make Cyprus a kingdom were probably busy fighting 100,000 outraged Orthodox Greeks on the island!

But why would Balian d’Ibelin go to Cyprus at this time?

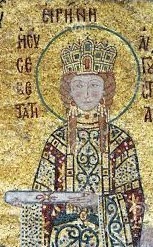

Because his wife, Maria Comnena, was a Byzantine princess. Not just that, she was related to the last Greek “emperor” of the island, Isaac Comnenus. She spoke Greek, understood the mentality of the population, and probably had good ties (or could forge them) to the Greek/Orthodox elites, secular and ecclesiastical, on the island. She had the means to help Aimery pacify his unruly realm, and Balian was a proven diplomat par excellence, who would also have been a great asset to Aimery.

If one accepts that Guy de Lusignan failed to pacify the island in his short time as lord, then what would have been more natural than for his successor, Aimery, to appeal to his wife’s kin for help in getting a grip on his unruly inheritance?

If Balian d’Ibelin and Maria Comnena played a role in helping Aimery establish his authority on Cyprus, it is nearly certain they would have been richly rewarded with lands/fiefs on the island once the situation settled down. Such feudal holdings would have given the Ibelins a seat on the High Court of Cyprus, which explains their influence on it. Furthermore, these Cypriot estates would most likely have fallen to their younger son, Philip, because their first born son, John, was heir to their holdings in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. John was first Constable of Jerusalem, then Lord of the hugely important port city of Beirut, and finally, after King Aimery’s death, became regent of the Kingdom of Jerusalem for his neice. Philip, on the other hand, was constable of Cyprusand later regent of Cyprus for Henry I ― notably despite the fact that his elder brother was still alive at the time.

Last but not least, no historian is able to explain why Aimery de Lusignan named John d’Ibelin Constable of Jerusalem in 1198, when John was just 19 years old. It has been suggested that the appointment was “just nominal” and didn’t carry real authority―but there is no evidence of this. On the contrary, the position clearly was powerful throughout the preceding century. Furthermore, even if nominal, why would Aimery appoint the young Ibelin to such a prestigious and lucrative post if Ibelins and Lusignans were still, as historians insist, bitter enemies?

Postulating a personal friendship between Aimery and John, on the other hand, would explain it. Given their age differences, the relationship of lord and squire is the most plausible explanation. Furthermore, the relationship of lord/squire brought men very close and gave each great insight into the personality, strengths and weaknesses of the other. It was also common for youths to serve a relative, and so quite logical for John would serve his cousin’s husband.

While this is all speculation, it is reasonable and does not contradict what is in the historical record. It is only in conflict with what modern historians have postulated based on a paucity of records. I hope, therefore, that readers will enjoy following me down this speculative road as I explore what mighthave happened in these critical years at the close of the 12thcentury.

In the coming weeks I'll be providing introductions to characters, and "sneak previews" from the Last Crusader Kingdom in the form of excerpts.

Meanwhile enjoy the Jerusalem Trilogy:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on July 29, 2017 01:20

July 22, 2017

An Empty Island Waiting to Welcome the Destroyer of Jerusalem?

The early history of the Kingdom of Cyprus is largely lost in the mists of time, and much of what we think we know―or what is currently accepted in academic circles―is dubious.

My novel, The Last Crusader Kingdom, looks at both the founding of the Kingdom of Cyprus in the years 1193-1199 from a new perspective and challenges conventional window. It is based on two revisionist theses (that I hope to develop more fully in a later non-fiction book on the subject.) The first of those thesis is presented below.

We know that Richard I of England, having conquered Cyprus in May 1191, sold it to the Knights Templar for 100,000 bezants in July of the same year. According to Peter Edbury, the leading modern historian of medieval Cyprus, their rule was “rapacious and unpopular,” resulting in a revolt in April 1192. Although a Templar sortie temporarily scattered the rebels, the causes of the revolt were hardly addressed and the latent threat of continued/renewed violence was clear. In the circumstances, the Grand Master of the Templars recognized that his Order would have to invest considerable manpower to regain control of the island. He also recognized that he did not have the resources to fight in both Cyprus and Syria. In consequence, he gave precedence (as he must) to the struggle on the mainland, the Holy Land itself, against the Saracens. The Templars duly returned the island to Richard of England.

Richard promptly sold the island a second time, this time to Guy de Lusignan. Guy de Lusignan had been crowned and anointed King of Jerusalem in 1186 in a coup d’etat engineered by his wife, Sibylla. Although widely viewed as a usurper, the bulk of the barons submitted to his rule in order to fight united against the much superior forces of Saladin that threatened the Kingdom. Guy, however, proceeded to prove the low-opinion of his barons correct by promptly leading the entire Christian army to an avoidable defeat on the Horns of Hattin on July 4, 1187. He spent roughly a year in Saracen captivity, while his Kingdom fell city by city and castle by castle to Saladin, until only the city of Tyre remained. Needless to say, this further discredited him with the surviving barons, prelates, and burghers of his kingdom. His claim to the crown of Jerusalem was undermined fatally when his wife, through whom he had gained it, died in November 1190. Although Guy continued to style himself “King of Jerusalem,” a fiction at first bolstered by King Richard of England’s support, by April 1192 King Richard gave up on him. Bowing to the High Court of Jerusalem, Richard acknowledged Conrad de Montferrat as King of Jerusalem. The sale of Cyprus to Guy was, therefore, a means of compensating him for the loss of his kingdom of Jerusalem.

Guy may have left for Cyprus at once, in which case he would have arrived in April 1192. However, this is far from certain because the Third Crusade was still being conducted. It is unlikely that Guy would have been able to convince many knights to accompany him as long as Richard the Lionheart was still fighting for Jerusalem and Jaffa. A more likely date for Guy’s arrival on Cyprus is therefore October 1192, after Richard’s departure for the West.

Guy was apparently accompanied by a small group of Frankish lords and knights whose lands had been lost to Saladin in 1187/1188 and not been recaptured in the course of the Third Crusade. The names of only a few are known. These include Humphrey de Toron, Renier de Jubail, Reynald Barlais, Walter de Bethsan, and Galganus de Cheneché. (Guy's older brother Aimery is notably absent.)

Guy was apparently accompanied by a small group of Frankish lords and knights whose lands had been lost to Saladin in 1187/1188 and not been recaptured in the course of the Third Crusade. The names of only a few are known. These include Humphrey de Toron, Renier de Jubail, Reynald Barlais, Walter de Bethsan, and Galganus de Cheneché. (Guy's older brother Aimery is notably absent.) Guy would have arrived on an island that was either still in a state of open rebellion or completely lawless. Admittedly, historian George Hill (who was actually an expert in ancient history, coins and iconography rather than a medievalist), tries to explain how Guy arrived on an island eagerly awaiting him by inventing (that is the only word one can use since he sites no source) the story that the Templars “slew the Greeks indiscriminately like sheep; a number of Greeks who sought asylum in a church were massacred; the mounted Templars rode through [Nicosia] spitting on their lances everyone they could reach; the streets ran with blood…The Templars rode through the land, sacking villages and spreading desolation, for the population of both cities and villages fled to the mountains.” (George Hill, A History of Cyprus, Volume 2: The Frankish Period 1192 – 1432,” Cambridge University Press, 1948, p. 37.)

There’s a serious problem with this lurid tale. (Quite aside from the technical one of lances being unsuitable for spitting multiple victims.) As Hill himself admits, the Templars had just fourteen knights on Cyprus and 29 sergeants; the Greek population of the island at this time, however, was roughly 100,000. Yes, in a surprise sortie to fight their way out of Nicosia and flee to Acre (as we know they did), the Templars would surely have killed many civilians, including innocent ones. It is unlikely, however, that the fleeing Templars would have taken the time to stop and slaughter people collected in a church; that would have given the far more numerous armed insurgents (who had forced them to seek refuge in their commandery in the first place) to rally, attack and kill them. They certainly did not have the time and resources to slaughter people in other cities and towns scattered over nearly 10,000 square kilometers of island. In short, we can be sure the Templars slaughtered enough people to be remembered with hatred, but not enough to break the resistance to Latin rule, much less to denude the island of its population. If nothing else, if they had broken the resistance, they would not have fled to Acre, admitted defeat and urged the Grand Chapter to return Cyprus to Richard of England!

Despite the absurdity of the notion that Guy arrived on a peaceful island willing to receive him without resistance, most histories today repeat a charming story. Namely: as soon as Guy arrived on Cyprus he sent to his arch-enemy Saladin for advice on how to rule it. What is more, the ever chivalrous and wise Sultan graciously responded that “if he wants the island to be secure he must give it all away.” (See Edbury, The Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades, 1191 – 1374, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 16.) Allegedly, based on this advice, Guy invited settlers from all the Christian countries of the eastern Mediterranean to settle on Cyprus, offering everyone rich rewards and making them marry the local women. According to this fairy tale, the disposed peoples of Syria, both high and low, flooded to Cyprus and were rewarded with rich fiefs, until Guy had only enough land to support just 20 household knights, but after that everyone lived happily ever after.

History isn’t like that, although―often―there is a kernel of truth in such legends. I think it is fair to assume that very many of the men and women who had lost their lands and livelihoods to the Saracens after Hattin did eventuallycome to settle on Cyprus, but I question that they arrived in the first two years after Guy acquired the island. The reason I doubt this is simple. The Knights Templar had just abandoned the island because it would be too costly, time-consuming and difficult to pacify. In short, whoever came to Cyprus with Guy in early or late 1192 would not have found an empty island―much less one full of happy natives waiting to welcome them with song and flowers. On the contrary, they were already in active rebellion against the Templars and ready to resist further attempts by the Latins to control and dominate them. Perhaps the one sentence about making the settlers marry local women is a hint to a more chilling reality: that after years of resistance to Latin rule, when the settlers finally came they found a local population with few young men but many widows.

Furthermore, we know that at no time in his life did Guy de Lusignan distinguish himself by wisdom or common sense. He had alienated his brother-in-law King Baldwin IV and nearly the entire High Court of Jerusalem within just three years of his marriage to Sibylla. He lost his entire kingdom in a disastrous and unnecessary campaign less than a year after he was crowned king. He started a strategically nonsensical siege of Acre that consumed crusader lives and resources for three years. He did nothing of note the entire time Richard the Lionheart was in the Holy Land. Is it really credible that he then took control of a rebellious island (that the Templars thought beyond their capacity to pacify) and set everything right in less than two years?

I think not. And Guy had only two years because he died in 1194, either in April/May or toward the end of the year depending on which source one consults. That is too little time even for a more competent leader to be the architect of Cyprus’ success. That honor belongs, I believe, to his older brother, the ever competent Aimery de Lusignan, who was lord of Cyprus not two years but eleven.

It was certainly Aimery, who obtained a crown by submitting the island to the Holy Roman Emperor, and it was Aimery who established a Latin church hierarchy on the island. Indeed, there is ample evidence of Aimery’s able administration of both Cyprus and, from 1197 to 1205, the Kingdom of Jerusalem as well. It was Aimery de Lusignan who collected the oral tradition for the laws of Jerusalem (that had worked so well) and had them written down in a legal codex known as The Book of the King. Thus, it was Aimery, who founded not only the dynasty that would last three hundred years, but also laid the legal and institutional foundations that would serve Cyprus so well into the 15thcentury. It is, in my opinion, far more likely that it was Aimery, not Guy, who brought settlers in―after first pacifying the native population and institutionalizing tolerance for the Orthodox church that mirrored the customs of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. It is this thesis that forms the basis of : The Last Crusader Kingdom: Founding of a Dynasty in 12th Century Cyprus.

My second revisionist thesis concerning the Ibelins will be the subject of my next entry.

Aimery de Lusignan is an important character in the Jerusalem Trilogy that covers the period leading up to the founding of the Lusignan dynasty on Cyprus.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on July 22, 2017 03:11

July 16, 2017

The Last Crusader Kingdom

The Jerusalem Trilogy followed the lives of Balian d'Ibelin and Maria Comnena through two decades of history from 1171 to the end of the Third Crusade in 1192. This was a crucial period, which saw the almost complete destruction of the crusader presence in the Middle East. It covered the dramatic Christian victory over Saladin in 1177, and the more devastating -- and unnecessary -- defeat of the Franks at the Battle of Hattin ten years later. Finally, in the third book of the trilogy, the dramatic defense of Tyre, the last Christian outpost in the Holy Land, and finally the course of the Third Crusade is described.

These events were momentous in their age. The shock of the annihilation of the Christian army at Hattin allegedly killed a pope and set in motion a massive military response: the Third Crusade. The Third Crusade, in turn, attracted the wealthiest and most powerful of Western monarchs -- Friedrich Barbarossa, Philip Augustus, and Richard the Lionheart. As a result, the period of history covered in the second two volumes of the Jerusalem Trilogy was well recorded by contemporaries had has been the focus of historical interest ever since. There are a wealth of primary and secondary sources that I could turn to for inspiration, guidance, plot and characters.

With the end of the crusade, the density and quality of contemporary sources and modern histories drops dramatically. Yet, life went on even after the momentous, eye-catching events ended. Furthermore, as readers will have noted, neither Balian nor Maria were dead.

The Last Crusader Kingdom is a novel set in the period following the Third Crusade. It is populated with familiar characters from that trilogy -- Balian and Maria, Aimery de Lusignan and his wife Eschiva, Queen Isabella and her 3rd husband Henri de Champagne, and more -- but it is not a sequel. It is a stand-alone novel.

The Last Crusader Kingdom attempts to explain two historical developments that historians skip over, ignore or admit ignorance about. First, the establishment of a Latin kingdom on the island of Cyprus under the Lusignans. Second, the rise of the Ibelin family to the most powerful, indeed dominant, noble family of Outremer. It is, in short, about historical events of significance, but largely lost to modern understanding because of an absence of sources -- primary or secondary -- that deal with this interlude in detail. In my next two entries, I will describe in greater detail the historical evidence available and the revisionist thesis pursued in this novel.

The Last Crusader Kingdom is also a "bridge" between the Jerusalem Trilogy and my next novels, which will describe the remarkable resistance of the barons of Outremer (led by the Ibelins) against the despotism of the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich II Hohenstaufen.

For those of you who missed The Jerusalem Trilogy, here are the links:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on July 16, 2017 03:00

July 8, 2017

Places for the Imagination: Acre

The Harbor of Acre todayIn Balian's time, Acre was the economic heart of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. After the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187, it became the de facto capital of the rump state as well. During the last hundred years of Frankish presence in the Levant, Acre became the principal seat of the Templar and Hospitaller Orders, as well as a the home of the largest "communes" of merchants from the various Italian city-states.

The Harbor of Acre todayIn Balian's time, Acre was the economic heart of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. After the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187, it became the de facto capital of the rump state as well. During the last hundred years of Frankish presence in the Levant, Acre became the principal seat of the Templar and Hospitaller Orders, as well as a the home of the largest "communes" of merchants from the various Italian city-states.  Acre's Waterfront TodayAs a major entrepot, Acre was famous for its cosmopolitan character. At any one time, it harbored a large transient population of sailors and caravan crews. Caravans bringing the riches of Asia and Arabia met and mingled with the crews of ships from all points West, including Ireland and Norway. Even the resident population was diverse and polyglot; Arabic, Greek, Syriac, Armenian, French and Italian would all have been spoken by people who called Acre home.

Acre's Waterfront TodayAs a major entrepot, Acre was famous for its cosmopolitan character. At any one time, it harbored a large transient population of sailors and caravan crews. Caravans bringing the riches of Asia and Arabia met and mingled with the crews of ships from all points West, including Ireland and Norway. Even the resident population was diverse and polyglot; Arabic, Greek, Syriac, Armenian, French and Italian would all have been spoken by people who called Acre home.Not terribly surprising, given this diverse and often disreputable nature of the population, Acre in the crusader era was notorious as a city of "low morals" and sinful pleasures. Pilgrims and crusaders alike complained about the "excessive" number of bath-houses. More than once, Richard the Lionheart was compelled to chase his men out of the "flesh-pots" of Acre and remind them of their crusader vows and duties.

The covered markets, suks, of Acre attracted both good and bad clientele. Getting a feel for Acre was thus an important part of my research -- even if the tame, touristy modern city could hardly convey the character of crusader Acre. The remains of the massive Hospitaller headquarters did, however, hint at the wealth, power and importance of the military orders. Here some pictures from my visit:

The covered markets, suks, of Acre attracted both good and bad clientele. Getting a feel for Acre was thus an important part of my research -- even if the tame, touristy modern city could hardly convey the character of crusader Acre. The remains of the massive Hospitaller headquarters did, however, hint at the wealth, power and importance of the military orders. Here some pictures from my visit:

Acre features particularly in the second and third books of the Jerusalem Trilogy.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on July 08, 2017 22:07

July 1, 2017

Places for the Imagination: Bethlehem

Church of the Nativity in BethlehemAfter Jerusalem itself, Bethlehem was probably the most popular pilgrimage destination in the Holy Land. (For more on the history of Bethlehem and the churches build there visit: Church of the Nativity) It had the advantage of being just over six miles distant from Jerusalem, making it comparatively easy for pilgrims to Jerusalem to visit Bethlehem as well.

Church of the Nativity in BethlehemAfter Jerusalem itself, Bethlehem was probably the most popular pilgrimage destination in the Holy Land. (For more on the history of Bethlehem and the churches build there visit: Church of the Nativity) It had the advantage of being just over six miles distant from Jerusalem, making it comparatively easy for pilgrims to Jerusalem to visit Bethlehem as well. In addition to its importance to Christianity, Bethlehem was the city in which the early Kings of Jerusalem were crowned, giving it political importance in the crusader period as well. It was, however, never a center of trade or industry, remaining -- right to the present time -- a city dependent primarily on religious tourism.

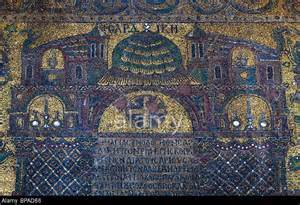

Although Bethlehem is the venue of only one important episode in the Jerusalem Trilogy, Bethlehem is nevertheless an important place for understanding and envisaging life in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. On the one hand, preserved in the Church of the Nativity are mosaics dating back to the reign of Constantine the Great -- an examples of the kind of mosaics that were even more common in crusader times. Furthermore, the church underwent extensive renovation in the reign of Amalric, including a series of spectacular mosaic murals. Not only are these considered exquisite and valuable examples of crusader art, they reflect the influence of King Amalric's Greek wife, Maria Comnena. Since Maria was also Balian's wife, these mosaics have a direct tie to Balian's life and provide an alluring hint to the artistic tastes in the world in which John d'Ibelin, Lord of Beruit grew up.

The Ibelins almost certainly maintained a residence in Jerusalem, and so trips to Bethlehem (for Christmas at least) were almost certainly part of the Ibelin routine. While the mosaics are generally considered the most important artistic feature, it was the Frankish cloisters at Bethlehem, pure Western Romanesque in style, that I personally found most beautiful:

The Ibelins almost certainly maintained a residence in Jerusalem, and so trips to Bethlehem (for Christmas at least) were almost certainly part of the Ibelin routine. While the mosaics are generally considered the most important artistic feature, it was the Frankish cloisters at Bethlehem, pure Western Romanesque in style, that I personally found most beautiful: Another, arguably more important, aspect of a trip to Bethlehem today is that the strong presence of Greek, Armenian and Syriac Christians in Bethlehem. They are a compelling reminder of how diverse Christianity was in the crusader period as well. Recent scholarship has documented a far greater tolerance for these other Christians than was previously assumed. For more about the treatment of Orthodox Christians in the crusader states please visit: Liberation or Oppression: Native Christians and the Crusaders.

Another, arguably more important, aspect of a trip to Bethlehem today is that the strong presence of Greek, Armenian and Syriac Christians in Bethlehem. They are a compelling reminder of how diverse Christianity was in the crusader period as well. Recent scholarship has documented a far greater tolerance for these other Christians than was previously assumed. For more about the treatment of Orthodox Christians in the crusader states please visit: Liberation or Oppression: Native Christians and the Crusaders. Bethlehem features in the first two books of the Jerusalem trilogy and is the scene of an important episode in Volume II.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on July 01, 2017 22:05

June 24, 2017

Places for the Imagination: Looking for Ibelin in Ibelin -- and Ascalon

The coast near Ibelin.

The coast near Ibelin.When writing a biographical novel about a man (Balian of Ibelin) who took his name from the place he was born, an author expects to find inspiration in the hero's birthplace. "Ibelin" was, after all, one of three castles built to defend Jerusalem from raids out Egyptian-held Ascalon. It was granted to Balian's father as a fief in the mid-1140s, and Balian was almost certainly born and raised there. He was so strongly associated with Ibelin that even after Ibelin was lost to Saladin, Balian and his heirs were still referred to as "Ibelins" -- generations after they derived their wealth and power from other fiefs and lordships such as Caymont, Beirut, Jaffa and Ascalon.

So I went to Ibelin in search of Ibelin. Only to find that there is nothing there.

I drove back and forth through the modern Yavne, the historical Ibelin, and could find not a trace of the crusader city or castle. It was obliterated by highways, shopping malls, apartment buildings and parking lots.

I continued just 18 miles down the coast to the ruins of Ascalon. Eighteen miles in this case did not bring a significant change in topography or climate, no sudden range of mountains, no gorges, lagoons, or desert. Both cities are located on the fertile plain along the Mediterranean coast. The lush vegetation and intensive cultivation of this landscape today echoes medieval descriptions of this coastal region being exceptionally fertile in the crusader era as well. Although Ascalon has a small harbor and Ibelin has none at all, Ascalon was never an important port.

Ascalon was, however, a very important city in the crusader period. It was held by the Egyptians until 1153, when it was finally taken after a long siege. The Egyptian defenders negotiated an honorable withdrawal and were not slaughtered, but they were expelled and replaced by Christian settlers. In 1187, Ascalon surrendered to Saladin after a feisty defense, but this time it was the Christian defenders, who accepted terms and thereby avoided slaughter and slavery. During the Third Crusade, Saladin evacuated and partially destroyed the city as the Frankish armies under Richard the Lionheart approached. Richard took the city and invested a great deal of time, effort and prestige into rebuilding it; reportedly he worked naked to the waist alongside the common soldiers to rebuild the defenses. Saladin's demand that he surrender Ascalon during the negotiations for a truce, almost caused the talks to fail. Eventually it was agreed that neither side would re-build or re-occupy Ascalon.

Many of the ruins that can be visited today date from the crusader period.

Remnants of the walls of Ascelon -- built in part by Richard the Lionheart?Ascelon is an important venue for events in the first and third volumes of the Jerusalem Trilogy.

Remnants of the walls of Ascelon -- built in part by Richard the Lionheart?Ascelon is an important venue for events in the first and third volumes of the Jerusalem Trilogy.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on June 24, 2017 03:07

June 16, 2017

Places for the Imagination: Oh, Jerusalem!

The "Jerusalem" in the title of Jerusalem Trilogy (Knight of Jerusalem, Defender of Jerusalem, and Envoy of Jerusalem) refers to the kingdom and king of the same name more than the city itself, yet it would have been impossible to write this trilogy of novels without having visited Jerusalem. Jerusalem was not only the capital of the kingdom by that name, it was the call, the magnet, the symbol and the heart of crusades and the crusader kingdoms.

While men fought and died for the abstract notion of "Jerusalem," and the city was also the ultimate pilgrimage destination of medieval Christians because it was the site of Christ's Crucifixion and Resurrection. Yet, despite all that, it remained a very real, secular and material city as well. Furthermore, it had a long history of habitation. For the inhabitants of Jerusalem in the period of my books (1170-1192), the city already had a rich history and its face and character were the product of diverse influences.

Jerusalem was, of course, originally a Jewish city. In the crusader period, the most important monument dating to the Jewish kings was the Tower of David, which formed an integral part of the medieval Citadel.

The Tower of David as it looks today.Jerusalem had also been a Roman city, most importantly, at the time of Christ. The venue of key episodes in Christ's life were Roman, e.g. the palace of Pontius Pilate. But although some Roman columns and mosaics survived and were integrated into later architecture, very little is recognizable today. The Mount of Olives, however, cannot have changed all that much. Here a picture as it looks today:

The Tower of David as it looks today.Jerusalem had also been a Roman city, most importantly, at the time of Christ. The venue of key episodes in Christ's life were Roman, e.g. the palace of Pontius Pilate. But although some Roman columns and mosaics survived and were integrated into later architecture, very little is recognizable today. The Mount of Olives, however, cannot have changed all that much. Here a picture as it looks today:

The Byzantine city has also largely been effaced what came afterwards, but here is a model that historians have developed based on archaeological research:

The Arabs were the most recent inhabitants of Jerusalem before the crusader period, and the most spectacular of their monuments was the "Dome of the Rock" erected on the Temple Mount. The Crusaders admired this structure greatly and far from defacing, damaging, destroying or neglecting it, they turned it into a church, the "Temple of God," and raised a cross over the dome in place of the half moon of Islam. Here are a couple of modern photos of the Temple Mount today, with the Dome of the Rock restored to a mosque.

The crusaders, however, also left a remarkable imprint upon Jerusalem. The most famous of the crusader/Frankish monuments is, of course, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher:

The crusaders, however, also left a remarkable imprint upon Jerusalem. The most famous of the crusader/Frankish monuments is, of course, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher:

But the Church of St. Anne is also a masterpiece of Frankish architecture which has survived so well because it was converted into a mosque in the period after Jerusalem was re-captured by Saladin. It is now a church again:

As the setting for a novel (are important parts of it), however, it was the more secular buildings and institutions that are important -- the markets and suks, the houses, inns, streets and plazas. Here some photos of remnants of the Frankish city:

But what was Jerusalem like when Balian actually lived there? Find at more at: The Heart of the Crusader Kingdom.

Jerusalem is particularly important as a venue in the first two books of the trilogy:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on June 16, 2017 22:16

June 11, 2017

Places for the Imagination

My novels are very character-centric with the main focus on character development and interaction. It is not surprising, therefore, that most of my novels are inspired by people. My historical biographies and biographical fiction, obviously, were inspired by real people, whose stories fascinate me ― General Friedrich Olbricht, Leonidas of Sparta, Balian d’Ibelin. Other stories, were inspired more by the “footnotes” to history ― a passing reference to an individual act of courage or compassion, a short description of a donor or a grave in a half-forgotten church, a local legend of dubious veracity that nevertheless captures the imagination….

Yet almost as important as people, places too inspire the imagination. I firmly believe that my interest in history and historical fiction started at the age of four when my father took me to the Coliseum in Rome. While my mother and older sisters took the guided tour, my father (wisely) decided a four year old would be bored by so much information. So he led me through the Coliseum alone and confined himself to the essentials. “This,” he told me, “is where the Romans fed the Christians to the Lions.” Now that was fascinating to a four year old.

I spent the rest of the afternoon (or however long the official tour took) trying to imagine where they had kept the lions? where the Christians? Was there no way to escape? What if a lion got loose among the spectators? You see how rapidly this can become a novel?

Of course, at four, no novel evolved, but the process of thinking about the places I visited as the site of historical events andthe stage for personal drama had started. It was helpful that Rome was only the start of a tour that took us to Florence and Venice, then up the Rhine and finally to Denmark and England, where we had family. Two years later we were in Brazil, and my imagination was ignited by a visit to the decaying city of Manaus on the Amazon. I wrote a tale about an Indian boy following the Amazon to the sea. (Any resemblance to childhood books about traveling down the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Mississippi are pure coincidence, of course….) I was in second grade.

At fifteen, the family returned to England. By now I loved to read as much as I loved to eat and breathe. I had not stopped writing since that book about the Amazon, but now I was living in the midst of history. We lived in Portsmouth, and Nelson’s flagship the Victory was within walking distance of our Victorian townhouse. The view out our front bay window was of the Solent, the Isle of Wight, the Royal Navy patrolling the grey, white-capped waves….

Although I never wrote that novel about the Royal Navy in the age of sail, I soon became fascinated with Britain in WWII. I visited the Imperial War Museum and touched the wings of Spitfires. I went to Tangmere, so close to Portsmouth, and gazed out across the peaceful, grass field, and imagined the gentle peace shattered by the telephone, the call to “scramble,” the roar of Merlin engines and the distant thud of the falling bombs. It took almost two decades and various false starts, but when Chasing the Wind was published in 2007 it was praised by one of the few surviving RAF fighter aces of that war, Wing Commander Bob Doe, as “the best book” he had ever read about the Battle of Britain. Doe wrote to me in a hand-written letter I treasure to this day. He said I “got it smack on the way it was for us fighter pilots.”

No amount of sales is a higher accolade for a historical novelist than for someone who lived through the time and events described in the book saying you got the it right. That is why, to this day, I consider Chasing the Wind (Kindle title: Where Eagles Never Flew) my best novel.

In coming weeks, I will be selecting some of venues relevant to the Jerusalem Trilogy and my current work-in-progress, The Last Crusader Kingdom. I hope my descriptions will inspire you to visit these unique places – either in my books or in person.

Published on June 11, 2017 00:36

June 4, 2017

Life and Lifestyle in the Crusader States: Hygiene

For the concluding essay in my series on life and lifestyle in the crusader states I wanted to look at one of those topics that are vital but sometimes viewed as taboo: hygiene.

One of the most persistent myths about the Middle Ages is that people did not bathe regularly and went around dirty and stinking. This is demonstratively not true. The Medievalists.net have published a good and lengthy post on the topic (Bathing in the Middle Ages), which provides a great deal of documentation and detail (such as Paris having 32 public baths in the 13th century and King Edward III installing taps for hot and cold running water in his palace at Westminster.) This entry is not intended to recount or compete with that or other sources, but rather focus on the unique traditions of "Outremer" or the Crusader States.

One of the most persistent myths about the Middle Ages is that people did not bathe regularly and went around dirty and stinking. This is demonstratively not true. The Medievalists.net have published a good and lengthy post on the topic (Bathing in the Middle Ages), which provides a great deal of documentation and detail (such as Paris having 32 public baths in the 13th century and King Edward III installing taps for hot and cold running water in his palace at Westminster.) This entry is not intended to recount or compete with that or other sources, but rather focus on the unique traditions of "Outremer" or the Crusader States.

All the Crusader States established in the course of and subsequent to the First and Third Crusades were in locations that had been under Greek influence since Alexander the Great at the latest. They had also been part of the Ancient and Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empires before coming under Arab and Turkish influence during the 8th and 9th centuries AD. This means that for the native population the predominant traditions with respect to personal hygiene came not from the Germanic tribes, Vikings or Celts, but from Greece, Rome, Egypt and Arabia.

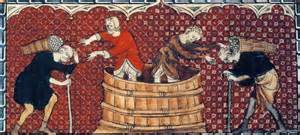

Whereas bathing in Western Europe is usually depicted in small, wooden tubs with curtains over them...

..the baths of any Roman town were generally gracious, spacious and elegant, often open to the skies in a series of atriums surrounded by colonnades. They were public spaces in which men conducted business and politics. The baths of Turkey and Arabia, while darker and more inward-looking, nevertheless were gracious with domed roofs and elegantly furnished with marble floors, glazed tiles, benches and fountains. They were less important for business and politics but all the more important culturally because of the emphasis Islam places on personal cleanliness. Both the Greco-Roman and Arab/Turkish traditions shared the principle of having both hot rooms for steaming/sweating (like a sauna) and cold rooms for washing off. Both also integrated massages with fragrantly scented oils into the bathing experience.

..the baths of any Roman town were generally gracious, spacious and elegant, often open to the skies in a series of atriums surrounded by colonnades. They were public spaces in which men conducted business and politics. The baths of Turkey and Arabia, while darker and more inward-looking, nevertheless were gracious with domed roofs and elegantly furnished with marble floors, glazed tiles, benches and fountains. They were less important for business and politics but all the more important culturally because of the emphasis Islam places on personal cleanliness. Both the Greco-Roman and Arab/Turkish traditions shared the principle of having both hot rooms for steaming/sweating (like a sauna) and cold rooms for washing off. Both also integrated massages with fragrantly scented oils into the bathing experience.

When the crusaders arrived in Outremer they found a large number of functioning bath houses, particularly of the later (Turkish/Arab) type, already in place. Far from scorning, abandoning, dismantling or altering their function, the Frankish settlers adopted them readily -- rather like ducks to water, one might say. Indeed, they started building their own, and archaeologists have identified a number of Frankish baths. These include baths in the Hospitaller and Templar headquarters in Jerusalem, at or near the monastery on Mt. Zion, at Atlit, a bathhouse on the Street of Jehoshephat near the convent of St. Anne, and another in the Patriarch's quarter. (For more details I recommend Adrian J. Boas' excellent works Jerusalem in the time of the Crusades and Crusader Archaeology.)

The Frankish settlers in Outremer adopted some of the bathing customs as well. Thus, while men and women bathed jointly in Western Europe, they probably bathed separately (either in separate spaces or at different times) in Outremer, although this is not 100% certain. The crusaders certainly adopted the custom of massages with scented oils stored in lovely glass vessels produced locally.

It wasn't only the bath houses that the Frankish settlers of Outremer inherited from their predecessors. They also inherited Roman aqueducts and sewage systems. The Greeks and Romans (both Ancient and Byzantine) were famous for building very sophisticated and extensive networks for bringing fresh water to the public fountains of their cities, often from many miles away. The Franks followed this example and built a number of their own. Thus while cities dating from the Roman period or earlier had Roman aqueducts that the crusaders merely needed to maintain, the construction of new castles, new towns or water-intensive industry such as sugar plantations, brought forth new aqueducts that clearly date from the crusader period.

In crusader times, the city of Caesarea was served by no less than three Roman aqueducts.All photo copyrights: www.romanaqueducts.infoLikewise, the ancient cities were served by extensive (and again very solid and sophisticated) sewage systems. These consisted both of stone faced drains and stone or pottery pipes. The Byzantines, for example, used pottery pipes to bring sewage down the outside of their residences from upper stories to underground sewage systems. Frankish castles had extensive latrines with sewers that emptied well below the level at which people lived. While roof top cisterns and tanks provided the means to flush out these latrines with water (as we know castles in England did a hundred and fifty years later), the archaeological evidence is insufficient to verify the practice in the Holy Land. Archaeological evidence of highly sophisticated drainage systems to divert underground streams, however, have been uncovered, and the level of engineering skills available to the Frankish settlers of Outremer should not, therefore, be under-estimated.

In crusader times, the city of Caesarea was served by no less than three Roman aqueducts.All photo copyrights: www.romanaqueducts.infoLikewise, the ancient cities were served by extensive (and again very solid and sophisticated) sewage systems. These consisted both of stone faced drains and stone or pottery pipes. The Byzantines, for example, used pottery pipes to bring sewage down the outside of their residences from upper stories to underground sewage systems. Frankish castles had extensive latrines with sewers that emptied well below the level at which people lived. While roof top cisterns and tanks provided the means to flush out these latrines with water (as we know castles in England did a hundred and fifty years later), the archaeological evidence is insufficient to verify the practice in the Holy Land. Archaeological evidence of highly sophisticated drainage systems to divert underground streams, however, have been uncovered, and the level of engineering skills available to the Frankish settlers of Outremer should not, therefore, be under-estimated.

To conclude, there may be a direct link between the hygienic conditions in Outremer and the hot-and-cold running water of Edward III and the Black Prince. The bulk of the crusaders, including Richard the Lionheart and Edward I of England, returned home, and by the time they went home they had probably become fond of the higher standards of hygiene enjoyed by the Frankish settlers -- the very standards that had induced the crusaders to ridicule the native "poulains" initially. (See Clash of Cultures) The large number of crusaders returning particularly to France, Germany and England may, in fact, explain the fact that Western Europe saw a flourishing of "bath house culture" in the 12th - 14th centuries.

Throughout my "Jerusalem" trilogy I endeavor to depict the lifestyle of the characters as realistically as possible.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

One of the most persistent myths about the Middle Ages is that people did not bathe regularly and went around dirty and stinking. This is demonstratively not true. The Medievalists.net have published a good and lengthy post on the topic (Bathing in the Middle Ages), which provides a great deal of documentation and detail (such as Paris having 32 public baths in the 13th century and King Edward III installing taps for hot and cold running water in his palace at Westminster.) This entry is not intended to recount or compete with that or other sources, but rather focus on the unique traditions of "Outremer" or the Crusader States.

One of the most persistent myths about the Middle Ages is that people did not bathe regularly and went around dirty and stinking. This is demonstratively not true. The Medievalists.net have published a good and lengthy post on the topic (Bathing in the Middle Ages), which provides a great deal of documentation and detail (such as Paris having 32 public baths in the 13th century and King Edward III installing taps for hot and cold running water in his palace at Westminster.) This entry is not intended to recount or compete with that or other sources, but rather focus on the unique traditions of "Outremer" or the Crusader States. All the Crusader States established in the course of and subsequent to the First and Third Crusades were in locations that had been under Greek influence since Alexander the Great at the latest. They had also been part of the Ancient and Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empires before coming under Arab and Turkish influence during the 8th and 9th centuries AD. This means that for the native population the predominant traditions with respect to personal hygiene came not from the Germanic tribes, Vikings or Celts, but from Greece, Rome, Egypt and Arabia.

Whereas bathing in Western Europe is usually depicted in small, wooden tubs with curtains over them...

..the baths of any Roman town were generally gracious, spacious and elegant, often open to the skies in a series of atriums surrounded by colonnades. They were public spaces in which men conducted business and politics. The baths of Turkey and Arabia, while darker and more inward-looking, nevertheless were gracious with domed roofs and elegantly furnished with marble floors, glazed tiles, benches and fountains. They were less important for business and politics but all the more important culturally because of the emphasis Islam places on personal cleanliness. Both the Greco-Roman and Arab/Turkish traditions shared the principle of having both hot rooms for steaming/sweating (like a sauna) and cold rooms for washing off. Both also integrated massages with fragrantly scented oils into the bathing experience.

..the baths of any Roman town were generally gracious, spacious and elegant, often open to the skies in a series of atriums surrounded by colonnades. They were public spaces in which men conducted business and politics. The baths of Turkey and Arabia, while darker and more inward-looking, nevertheless were gracious with domed roofs and elegantly furnished with marble floors, glazed tiles, benches and fountains. They were less important for business and politics but all the more important culturally because of the emphasis Islam places on personal cleanliness. Both the Greco-Roman and Arab/Turkish traditions shared the principle of having both hot rooms for steaming/sweating (like a sauna) and cold rooms for washing off. Both also integrated massages with fragrantly scented oils into the bathing experience.When the crusaders arrived in Outremer they found a large number of functioning bath houses, particularly of the later (Turkish/Arab) type, already in place. Far from scorning, abandoning, dismantling or altering their function, the Frankish settlers adopted them readily -- rather like ducks to water, one might say. Indeed, they started building their own, and archaeologists have identified a number of Frankish baths. These include baths in the Hospitaller and Templar headquarters in Jerusalem, at or near the monastery on Mt. Zion, at Atlit, a bathhouse on the Street of Jehoshephat near the convent of St. Anne, and another in the Patriarch's quarter. (For more details I recommend Adrian J. Boas' excellent works Jerusalem in the time of the Crusades and Crusader Archaeology.)

The Frankish settlers in Outremer adopted some of the bathing customs as well. Thus, while men and women bathed jointly in Western Europe, they probably bathed separately (either in separate spaces or at different times) in Outremer, although this is not 100% certain. The crusaders certainly adopted the custom of massages with scented oils stored in lovely glass vessels produced locally.

It wasn't only the bath houses that the Frankish settlers of Outremer inherited from their predecessors. They also inherited Roman aqueducts and sewage systems. The Greeks and Romans (both Ancient and Byzantine) were famous for building very sophisticated and extensive networks for bringing fresh water to the public fountains of their cities, often from many miles away. The Franks followed this example and built a number of their own. Thus while cities dating from the Roman period or earlier had Roman aqueducts that the crusaders merely needed to maintain, the construction of new castles, new towns or water-intensive industry such as sugar plantations, brought forth new aqueducts that clearly date from the crusader period.

In crusader times, the city of Caesarea was served by no less than three Roman aqueducts.All photo copyrights: www.romanaqueducts.infoLikewise, the ancient cities were served by extensive (and again very solid and sophisticated) sewage systems. These consisted both of stone faced drains and stone or pottery pipes. The Byzantines, for example, used pottery pipes to bring sewage down the outside of their residences from upper stories to underground sewage systems. Frankish castles had extensive latrines with sewers that emptied well below the level at which people lived. While roof top cisterns and tanks provided the means to flush out these latrines with water (as we know castles in England did a hundred and fifty years later), the archaeological evidence is insufficient to verify the practice in the Holy Land. Archaeological evidence of highly sophisticated drainage systems to divert underground streams, however, have been uncovered, and the level of engineering skills available to the Frankish settlers of Outremer should not, therefore, be under-estimated.

In crusader times, the city of Caesarea was served by no less than three Roman aqueducts.All photo copyrights: www.romanaqueducts.infoLikewise, the ancient cities were served by extensive (and again very solid and sophisticated) sewage systems. These consisted both of stone faced drains and stone or pottery pipes. The Byzantines, for example, used pottery pipes to bring sewage down the outside of their residences from upper stories to underground sewage systems. Frankish castles had extensive latrines with sewers that emptied well below the level at which people lived. While roof top cisterns and tanks provided the means to flush out these latrines with water (as we know castles in England did a hundred and fifty years later), the archaeological evidence is insufficient to verify the practice in the Holy Land. Archaeological evidence of highly sophisticated drainage systems to divert underground streams, however, have been uncovered, and the level of engineering skills available to the Frankish settlers of Outremer should not, therefore, be under-estimated. To conclude, there may be a direct link between the hygienic conditions in Outremer and the hot-and-cold running water of Edward III and the Black Prince. The bulk of the crusaders, including Richard the Lionheart and Edward I of England, returned home, and by the time they went home they had probably become fond of the higher standards of hygiene enjoyed by the Frankish settlers -- the very standards that had induced the crusaders to ridicule the native "poulains" initially. (See Clash of Cultures) The large number of crusaders returning particularly to France, Germany and England may, in fact, explain the fact that Western Europe saw a flourishing of "bath house culture" in the 12th - 14th centuries.

Throughout my "Jerusalem" trilogy I endeavor to depict the lifestyle of the characters as realistically as possible.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on June 04, 2017 01:21

May 28, 2017

Life and Lifestyle in the Crusader States: Cuisine

Since Ancient Greece, food has been more than just a means of fueling the human body; it has been recognized as a pleasure. All cultures surround at least some meals with ritual and custom, particularly meals shared with strangers or guests. Most regions have distinct cooking traditions, and everywhere cooks are valued. Medieval Europe was no exception, and most readers will have heard of extravagant medieval feasts featuring game such as beavers and swans or spectacles such as pies full of live birds.

We can assume that people in the crusader states were no exception to this general rule. Furthermore, residents in the crusader states benefited from being in one of the most fertile regions of the world ― no, the Kingdom of Jerusalem was not located in the North African desert used to film The Kingdom of Heaven, but rather occupied the biblical “land of milk and honey.”

Furthermore, like cosmopolitan cities today, the crusader states sat at a cross-roads of civilizations, which ensured a variety of culinary traditions lived side-by-side ― and very likely influenced one another. On the one hand the inhabitants of "Outremer" inherited the cooking habits of earlier Mediterranean civilizations including invaders from the Arabian peninsula and the Near Eastern steppes, while on the other hand they also enjoyed the customs brought out to the Holy Land by Latin settlers from Northern and Western Europe. That said, I’m going to admit that we don’t have a lot of evidence for exactly what this mix of cuisines actually looked like ― much less how it tasted!

We do, however, have considerable information about what ingredients were available to the residents of Outremer, and this provides a basis for speculating and imagining at least some features of crusader cuisine. Before speculating on the content of crusader cooking, however, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the crusader states are credited by some historians (namely Adrian Boas) with an important culinary innovation: fast food.

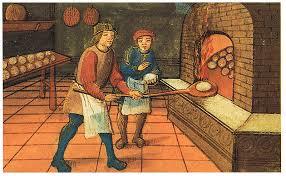

The large number of pilgrims flooding the Holy City produced a plethora of cheap inns and hostels, places where pilgrims could bed down for the night. However, cheap places to sleep, then as now, did not offer meals, and so pilgrims had to eat elsewhere. A general shortage of firewood meant that not only was bread baked centrally at large ovens (usually co-located with flour mills), but also that “cook shops” producing large quantities of food over a single oven was more practical than everyone cooking for themselves. The result was the medieval equivalent of modern “food courts” ― streets or markets on which a variety of shops offered pre-prepared food. The results were probably not all that different from today; the area in Jerusalem on which these cook-shops concentrated was known as the market (or street) of Bad Cooking ― the Malquisinat.

And now to the ingredients:

The staple of the medieval diet was bread derived from grain, and this was true in the Holy Land as well as in the West. Milling was a prerogative of the feudal elite, and bakeries were generally co-located with mills. In rural areas this was usually near the manor, and in urban areas the bakeries were well distributed around the city for convenience, something well recorded archeologically. The primary grains popular in the Holy Land in the crusader period were wheat and barley, but millet and rice are also recorded, whereby rice was not converted into bread but instead eaten by the native population that retained Arab/Turkish eating habits that included the consumption of rice.

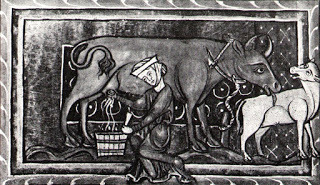

Animal products were the second pillar of the medieval diet, highly valued, and correspondingly exploited fully from the meat to innards. Of the large domesticated animals, sheep and goats were the most common type of livestock in the Holy Land, and the Hospitallers recommended lamb and kid for patients in their hospitals. Jerusalem, however, also had a cattle market and a pig market. The latter is particularly noteworthy given the fact that both Jews and Muslims view pigs as unclean. However, a large (Orthodox) Christian population continued to live in the Holy Land throughout the Muslim occupation of Jerusalem, so pigs would have been bred and did not need to be imported. There is also evidence of camels in the crusader states, and camel meat is considered a delicacy in much of the Middle East. However, it is questionable that the Franks adopted the habit of eating camel meat. The camels of Outremer were more probably used primarily as beasts of burden not as food.

Of the smaller animals, poultry and fish certainly belonged to the crusader diet. Chicken coups and indeed whole villages specialized in poultry production have been identified by archaeologists. Fish, on the other hand, was vitally important becaus meat was prohibited on “fasting days” such as throughout Advent, Lent and on Fridays. In the second century of the crusader states, the population of Outremer was clustered along the coastline, and fish from the Mediterranean would have been plentiful and fresh. This would have represented a great enrichment of crusade cuisine unknown in most of continental Europe, where it was impossible (using medieval means of preservation) to get fish from the catch to the table in a form resembling “fresh” except in port towns. The Mediterranean yields some of the most delicious fish, including squid and octopus, and shellfish and crab remains have been found in crusader archaeological digs.

Game, according to Hazard*, was available in the first century of crusader rule in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. He lists gazelles, boars, roedeer, hares, partridge and quail. However, after the territorial losses following the defeat at Hattin, population density would not have allowed for large tracts of fertile land in which game could thrive, so game probably disappeared from the tables of the elite in the states on the mainland. Cyprus, on the other hand, was not densely populated, and allegedly still had some exotic wildlife (including lions) that must have tempted medieval hunters.

Animal products such as eggs, milk, butter, yogurt, and cheese were, on the other, consumed in the Holy Land in the crusader period, the latter being more important than the former. While milk and butter is hard to preserve fresh, cheese is a product with a comparatively long shelf-life. Furthermore, cheese can be produced from cattle, sheep, goat and camel milk. A comparatively wide variety of cheese would, therefore, most probably have been available. Yogurt, being a product used heavily in the Middle Eastern diet, would likewise probably have been known to crusaders, though probably less readily embraced.

Vegetable varieties in contrast would have seemed limited by modern standards. Legumes were the primary vegetables of the Middle Ages, and in the crusader states the most important vegetables were beans including broad beans, various lentils, cabbage, onions, peas and chickpeas. However, fresh cucumbers and melons were both native to the Levant and probably formed part of the crusader diet.

Fruits were also a key component of crusader cuisine. The residents of Outremer had ready access to fruits such as oranges and lemons that were considered outrageous luxuries in the West, yet grew in abundance in the Levant. Along with typical and familiar fruits from the West such as apples, pears, plums and cherries, Outremer cultivated orchards of pomegranates (particularly around Ibelin and Jaffa). Figs, dates, carobs and bananas were also native to the region and continued in cultivation during the crusader period. But arguably most important of all were grapes, which ― of course ― were eaten fresh and dried (raisins and currants) and pressed/fermented as wine.

Other important trees that yielded important dietary supplements were almonds, pistachios and, most important of all, olives. Olive oil is and was fundamental to Middle Eastern cuisine. It is the primary source of cooking oil, used both as a means of cooking and a supplement for consistency and taste.

The most famous olive trees in the Holy Land: the Mount of Olives outside of JerusalemAnd then there are the “additives” that make such a difference to the taste of food: honey, sugar, herbs and spices ― all ingredients found readily in the crusader states. Indeed, refined sugar was one of the main exports of the crusader states, which had many sugar cane plantations in the Jordan Valley, along the coast and later on Cyprus. Honey is also listed as one of the major products of Cyprus during the crusader period. A variety of herbs such as rosemary, thyme, and oregano grow in abundance, as well as mustard seed and garlic. More significant is that many of the spices coveted by the West and only available at very high prices in Europe passed through the ports of Outremer. The coastal cities and Jerusalem had spice markets in which these exotic, high-value products were available in quantities and at prices unimaginable in the West. Thus crusader cuisine would have been enriched by the use of cinnamon, cumin, cardamon, cloves, ginger, lavender, licorice, nutmeg, sesame, saffron, and pepper among others.

The most famous olive trees in the Holy Land: the Mount of Olives outside of JerusalemAnd then there are the “additives” that make such a difference to the taste of food: honey, sugar, herbs and spices ― all ingredients found readily in the crusader states. Indeed, refined sugar was one of the main exports of the crusader states, which had many sugar cane plantations in the Jordan Valley, along the coast and later on Cyprus. Honey is also listed as one of the major products of Cyprus during the crusader period. A variety of herbs such as rosemary, thyme, and oregano grow in abundance, as well as mustard seed and garlic. More significant is that many of the spices coveted by the West and only available at very high prices in Europe passed through the ports of Outremer. The coastal cities and Jerusalem had spice markets in which these exotic, high-value products were available in quantities and at prices unimaginable in the West. Thus crusader cuisine would have been enriched by the use of cinnamon, cumin, cardamon, cloves, ginger, lavender, licorice, nutmeg, sesame, saffron, and pepper among others. Given the materials the cooks of Outremer had to work with and the inspiration they could draw from their Greek, Arab and Turkish neighbors, I think we can assume that ― despite the presence of some mediocre fast-food joints in the Market of Bad Cooking ― the chefs and housewives throughout the crusader states could produce some truly wonderful cuisine.

* Hazard, Harry W. ed, A History of the Crusades IV: The Art and Architecture of the Crusader States.

See also: Andrian J. Boas, Domestic Settings: Sources on Domestic Architecture and Day-to-Day Activities in the Crusader States, Brill, 2010.

Daily life, including cooking and food, is depicted as accurately as possible in my novels set in Outremer:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on May 28, 2017 00:16