Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 44

October 30, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Humility

The ideal knight was not a braggart. Medieval society as a whole, after all, was dominated by a religion in which the Savior himself was a humble man who preached that "the meek shall inherit the earth." The Church condemned both pride and displays of wealth and consumption. Indeed, pride was one of the seven deadly sins. That medieval knights often did not live up to this ideal goes without saying: chivalry was always the ideal, not reality. There would not have been so much preaching against excessive consumption and extravagant dress and pageantry if knights and noblemen had not commonly been guilty of engaging in all of it.

Balian’s humility can best be judged by the fact that despite being viewed by Arab chroniclers as “like a king” after Hattin, Christian accounts singularly fail to describe a man who was "lording it" over his fellows. Indeed, even the chronicles that detest him, such as the Itinerarium Peregrinorum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, attack him for other failings. They call him cruel, fickle and faithless -- all because he did not do Richard of England's bidding, but pursued his own policies. Yet they notably fail to allege that the man who was "like a king" (and step-father of the legitimate queen of Jerusalem) was excessively proud or haughty.

Obviously, the absence of allegations of pride does not prove humility either. Yet when one considers the fact that Ibelin was seen as virtually the only nobleman in the entire Kingdom of Jerusalem withstature and authority, it is remarkable that he never himself laid claim to a position of per-eminence. Conrad of Montferrat, for example, who put up a spirited and successful defense of Tyre, almost at once laid claim to a lordship he had not inherited, and later laid claim to the crown itself. He has also gone down in history as grasping, intriguing, selfish and excessively ambitious, as a man willing to cut almost any deal with Saladin for the sake of becoming King of Jerusalem.

Balian d'Ibelin in contrast acted consistently in cooperation with his fellow surviving barons, usually through the High Court, or at a minimum with prominent nobles such as Reginald de Sidon, the Tiberias brothers, and Pagan of Haifa. Given the fact that his eldest son later fought an entire war to defend the institution of the High Court of Jerusalem (i.e. the barons sitting collectively), it is fair to presume that Balian raised his son to respect this body and collective leadership instead of asserting one's individual rights. In the medieval context, that is a remarkable mark of humility.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on October 30, 2016 01:05

October 23, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Piety

Chivalry was from its inception closely allied to Christianity. It emerged in the 12th century, in a period of the crusades and monasticism, and it lost its hold on people with the Reformation. Some historians go so far as to postulate that chivalry was intentionally developed/encouraged by the Church as a means to "tame" or "direct" the violence of fighting men. While that seems far fetched for such a secular ideal (that tolerated a great deal of illicit love!), throughout the Age of Chivalry the Catholic Church reigned unchallenged in the spiritual realm, and chivalry paid respect to her. Thus by the 13th century a vigil in a church or the dedication of a sword at the altar had become a common (though not essential) part of the knighting ceremony.

It can hardly surprise, therefore, that piety was a knightly ideal. The "perfect" knight, was a devout Christian who gave alms to the Church. Indeed, the most fundamental duty of a knight was to protect "the helpless" and "the Church." Because churchmen were not supposed to bear arms or draw blood, priests and monks, like women, children and invalids were considered the "helpless" people that knights vowed to protect.

Balian's piety is documented. In early 1187, when he was part of a delegation sent by King Guy to Count Raymond of Tripoli to try to reconcile the two. The other military members of that delegation were lured into a lop-sided battle which resulted in a massacre of the Christian knights. Balian, however, missed this debacle at the Springs of Cresson. The reason: he had stopped to hear mass and was late for the rendezvous.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on October 23, 2016 01:12

October 16, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Courtesy and Cleanliness

These are two of my favorite knightly virtues because people so often ignore them.

Courtesy, however, was essential in a culture that placed a high value on mutual love and earning the favor of a lady (as opposed to just abducting or buying her). Furthermore, courtesy in the High Middle Ages was also expected of young people when addressing their elders and of people of lower rank when addressing their superiors. Indeed, courtesy as an ideal was supposed to regulate communications between all people of "worth" in the Age of Chivalry, and a mastery of courtesy was demanded of children and admired in adults.

As for cleanliness, many people nowadays still imagine that people in the Middle Ages did not place a value on cleanliness and even abhorred it. The fact that people did not bathe frequently in the 18th century is extrapolated backwards, and I’ve read far too many books set in the crusades that portray the Muslims as clean and the Christians as filthy and stinking. Not true.

Bathing was much more difficult when water did not come running hot and cold out of a tap, but that if anything made it more valued. It was an important ritual of knighthood itself, and is frequently portrayed in medieval manuscripts. The rich had private baths, and the poor went to bath houses. In the hotter climate of southern Europe, from Spain to Greece, where the Romans had built large bath houses, the tradition continued particularly strong, and in the crusader kingdoms baths were built in the Turkish tradition – by Christians.

In fact, many pilgrims who came to the crusader kingdoms, were initially shocked by the extent to which the local population “indulged” in the pleasures of these bathhouses. The objection, however, was not to the concept of cleanliness but rather to the associated pleasures of massages and scented oils and the ambiance.

As a renowned diplomat, capable of intermediating between Tripoli and Lusignan and negotiating on multiple occasions with Saladin, Balian would have had to have at the least a diplomatic manner and a courteous tongue. Admittedly, diplomacy isn't all about nice words, but it has been defined as "the ability to tell someone to go to hell in such a way that they look forward to the trip." I think we can assume, therefore, that Balian had mastered the virtue of courtesy to a high degree. As for cleanliness, since Balian was one of the “local” lords, born in the Holy Land, we can assume he was a frequent visitor to bath houses. He, more than most knights in the west at this time, would have fulfilled the knightly virtue of “cleanliness.”

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on October 16, 2016 01:24

October 9, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Preserverance and Diligence

It is unlikely that the words "preserverance" or "diligence" spring readily to mind when one thinks of chivalry -- which is why I find them so insightful additions to the list of knightly virtues. Of course, if one looks at the romances of the Age of Chivalry, these virtues are represented in abudance. The heroes of chivalry were on a quest for greater glory, honor or love and they usually encounter many difficulties along the way. Without perserverance and diligence, success would be impossible.

Real life in the High Middle Ages also required a great deal of preserverance and diligence. Knights were not born: they were made by years and years of service and training as pages and squires. Few men were knighted before they had endured many falls in the tiltyard, endless banquets requiring an understanding of protocol and manners, and hours of classroom instruction learning reading, writing, accounting and more.

Balian d'Ibelin must have had more than his fair share of both of these virtues. As younger son he probably had to work harder to make his way in the world as a young man. Which may explain why he was so tenacious as an older man. What is certain is that having lost his entire inheritance in 1187, he diligently rebuilt his fortunes -- step by step and marriage by marriage -- until the once obscure and insignificant family had become the most powerful in the Latin east. The House of Ibelin was so predominant and so influential, in fact, that Ibelins more than once challenged ruling monarchs, including the Holy Roman Emperor. They served as regents and constables, and their daughters married kings.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on October 09, 2016 05:00

October 2, 2016

Interview with Char Newcomb - Author of "For King and Country"

This week I interrupt my series on chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin to bring you a special treat: an interview with Charlene Newcomb, Author of For King and Country, Book II in the Battle Scars Series

Char, welcome back to Schrader’s Historical Fiction Blog. As I said last time, we have a lot in common, and it’s a pleasure to have you with me again for an interview about your latest release For King and Country -- especially now that it has received a B.R.A.G. Medallion and, as an HNS “Editor’s Choice,” is long-listed for the Historical Novel Society 2017 Indie Award!

Let’s jump right in by starting with a question I asked last time as well, but as a means to refresh readers’ memory.

1. What inspired you to write this particular series of books?There is that commonality we share: both us influenced by film or television. Where your Balian d’Ibelin series was inspired by the film, Kingdom of Heaven, my inspiration came from a BBC Robin Hood series. That Robin had served Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade and my knowledge of the man and that particular event was minimal, but I was intrigued. I dove online and discovered works of contemporary chroniclers’ fully translated. Richard the Lionheart’s story has been told many times in fiction and non-fiction, so I created a story of fictional knights who served him, showing how war, politics, and love impacted a naïve young man and a seasoned veteran.

2. Book I in the series, Men of the Cross, covers the entire Third Crusade. That’s roughly two years of action packed history that is one of the most well-documented two years in the entire 12thcentury. For the Third Crusade you had a number of excellent primary sources, English, French and Saracen. This book in contrast, covers a sliver of time, a little less than a year, if I’m calculating correctly, and the events are not historical but invented, albeit against a background of a real period in history. What made you change your pace? And how did you evolve this particular plot?

Though actual events of the Third Crusade feature prominently in Men of the Cross, the focus of the Battle Scars series has always been on the men who served the Lionheart. Henry de Grey, a young knight, has been profoundly impacted by what he has seen and done in God’s name. He is disillusioned by the war and, by the end of Book I, has accepted and welcomed his feelings for fellow knight Stephan l’Aigle. One theme of Book II shows the trials of their relationship as the knights return to England. Their secret love must remain hidden, though Henry knows his father expects him to marry and provide an heir. While Henry tries to avoid Edward de Grey’s matchmaking, Stephan, and Sir Robin have been tasked by the queen to identify King Richard’s enemies in England. King Richard is being held prisoner by the Holy Roman Emperor and his brother John plots with Philip of France to usurp the throne. John has supporters in England and Henry is now defending the king against other Englishmen. Politics and treachery threaten their own families and friends. Indeed, their own families may have ties to John.

Another theme of For King and Country is delving deeper into the building of a new Robin Hood origins story, what I have referred to as the ‘seeds’ of the legend. Robin, Allan, and Little John were introduced in Book I. Their story arcs, and the introduction of Marian, Much, Tuck, and Will, allowed me to build on that in Book II.

The novel does end with an actual major event, the Siege of Nottingham. Richard has been released from captivity, returns to England, and is reunited with my fictional characters who served him in the Holy Land.

3. Since you didn’t have the same wealth of sources for this slice of history, what were your principle research tools?

Interestingly, one of the shortest chapters of the book England Without Richard, 1189-1199, deals with the year 1193. For King and Country focuses on John’s efforts to fortify his English castles, but John’s whereabouts in the contemporary chronicles and biographies - with a couple of exceptions - are not well documented. That freed me up to fill in gaps, to place John and also his mother, Queen Eleanor, in a few crucial scenes. The chronicles did briefly cover the Siege of Nottingham, but Trevor Foulds’ excellent article on that event was a fantastic resource. In addition to biographies of Richard, John, and Eleanor, my principle research tools were books on medieval Nottingham, Lincolnshire and York, resources about culture, housing, life, and society in medieval times.

4. You gave a wonderful interview to Catherine Curzon on her blog “A Covent Garden Gilflirt’s Guide to Life.” (http://www.madamegilflurt.com/2016/05/an-american-in-nottingham-writing-robin.html) Here you described your disappointment when first visiting Nottingham Castle to discover it was dominated by post-1500 additions — a phenomenon that has frequently plagued my research as well! (Try finding anything crusader in modern Israel….) You were fortunate to find a written resource that provided details. But let’s return to your trip to England. What impact did it have on your writing? Was it all a disappointment? Or did visiting the scenes of your novel enable you to learn things you would not have been able to find in written sources? If so, what? Were there aspects of the novel that you changed because of travel to England?

It was a matter of location and fate that led me to Nottingham in 2010 and had nothing to do with research for my novel, but rather research for my sabbatical project. I was traveling to the United Kingdom to do site visits at university libraries. As I reached out to UK colleagues and plotted my visits, I realized that Nottingham, which I knew little about except what I’d seen in Robin Hood movies and television, was centrally located. I rented a flat there for three weeks, and managed to get to Nottingham Castle as a tourist. At that time, I wasn’t even thinking about writing a novel based in medieval Nottingham. I hadn’t even started writing Men of the Cross, which centered on the Third Crusade. But by 2013, as I was working on Men, I realized I wanted to – or perhaps was compelled to – follow my fictional characters back to England for a sequel. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to return to Nottingham for a look as a researcher, so my visits were virtual through my own photos from 2010 and others online, and through what I read, including the book Nottingham Castle: A Place Full Royal by Christopher Drage. I did get to Nottingham just a few weeks ago and find I appreciate the Castle and The Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem even more now that I have better grasp of their histories.

5. You had lots of fun writing this book. What scene did you like writing most? What scene is your favorite (which may or may not be same thing, of course….)?

I did have fun, which is one reason I like to call this series an historical adventure. There are many serious themes running through both novels – war, treason, PTSD, forbidden love, family loyalties tested – but life is sprinkled with humorous moments and I wanted to find places within all that emotion to make the reader smile. Without giving too much away, I loved writing the earthquake scene (which got added in my last month of final edits!) and the scene of Robin telling family and friends how he met Queen Eleanor. As for my favorite scene, that is tough because I have at least three, if not more, and they all involve spoilers. Let me tell you that one involves main character Henry, Queen Eleanor, Little John, and a new female character named Elle.

6. Tell us more about the series Battle Scars as a whole. How many books will there be and what period will it cover?

I am currently writing Book III, Swords of the King, which takes place during the last few years of King Richard I’s reign. All three Battle Scars books include the origins of the men who one day turn outlaw and become that band of Merry Men. I am fairly certain there will be 4thbook in the series that turns the focus to the Robin Hood legend during King John’s reign. That particular novel is just a tiny acorn at the moment, but as I write Book III, I think it will firmly grasp my imagination and take root. With luck, Swords of the King will be published in 2018.

7. Tell us a little more about your readers? Who did you set out to reach with this series? Men? Women? Young people? Professionals? Why should they be interested in these books? What can they get out of them?

I thought laying the foundations of a new Robin Hood origins story might attract readers, though Robin and his “Merry Men” are not the focus of novels at this point. A few people did find Men of the Cross because of the Robin connection. Others appeared to love stories about the crusades, including a few readers, like you, from academic backgrounds with degrees in history or political science with extensive knowledge of medieval history. There may be more women reading than men—one female reader told me her husband was interested when he saw the book cover of Men, but when he heard there was a romance element, he said “no thank you.” It wouldn’t have mattered if it was romance of the male/female variety or male/male (m/m). Either way, it wasn’t for him. Other male readers (both straight and gay) have loved both the action and the gay romance, and as one female reader (who had not read a m/m work before) emailed me: “Love is universal…and if the characters are well-drawn, you want to see them together."

I would love to think that fans of great writers Sharon Kay Penman and Elizabeth Chadwick would find my books as many of their novels cover the same time period and feature Richard the Lionheart, John Lackland (the future evil King John) and Eleanor of Aquitaine. A few have. I am still learning to write great battle scenes like Bernard Cornwell (and Penman and Chadwick have their share, too). Readers who enjoy tales of adventure against the backdrop of war—sometimes brutal and bloody—and political intrigue with romance and a bit of humor, may find Battle Scars right up their alley. Join me in the 12th century and I think you will feel I have transported you back to medieval times.

Thank you for taking time to answer my questions, Char. It’s been fun talking to you — even if only virtually. Good luck with sales!

Thank you, Helena!

Find Char online at :Website: http://charlenenewcomb.comFacebook: http://www.facebook.com/CharleneNewcombAuthorTwitter: http://twitter.com/charnewcombBuy the books: http://author.to/CharNewcomb

Published on October 02, 2016 05:00

September 25, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Love

Whereas prowess has been a manly virtue since the start of time, the idea that loving (as opposed to abducting, mastering, humiliating, controlling, abusing, subjugating etc.) a woman was a manly virtue that increased a man's stature among men is arguably the most remarkable aspect of chivalry altogether. Indeed, love for a lady became a central -- if not the central -- concept of chivalry in literature.

Significantly, the chivalric notion of love was that it must be mutual, voluntary, and exclusive – on both sides. The troubadours of the Age of Chivalry put love for another man’s wife on an equal footing with love for one’s own -- but only provided the lady returned the sentiment. The most famous of all adulterous lovers in the age of chivalry were, of course, Lancelot and Guinevere, closely followed by Tristan and Iseult. Yet, in the tradition of chivalry, love could also occur between husband and wife. In fact, some of the most influential romances such as Erec et Enide by Chrétien de Troyes or Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzivalrevolve in part or in whole around the love of a married couple.

Balian's relationship with his wife Maria Comnena is one of the features of his life that attracted me to him as a worthy subject of a novel. Maria Comnena came from the most exalted royal family in Christendom, the Imperial family of the Eastern (Greek or Byzantine) Roman Empire. As such, she had been deemed fit to marry the King of Jerusalem himself, and came to Jerusalem as a bride of 12 or 13 years old. She was anointed Queen of Jerusalem at the time of her marriage to King Amalric.

She was no more than 22 or 23 years old at the time of his death, and received the immensely wealthy and strategically important barony of Nablus as her dower portion. That is, she held Nablus for as long as she lived but it reverted to the crown at her death; she could not pass it on to heirs or bequeath it at will. Nablus was a center of manufacturing, known for its perfumes and soaps. It also owed 80 knights to the feudal army. It was, in short, more than sufficient to support a woman in luxury and security. Maria Comnena had no need to remarry and the customs of the Kingdom of Jerusalem did not permit a widow to be coerced into a second marriage. Officially, the king was supposed to "suggest" three candidates and the widow was supposed to choose between them, but the law was consistently ignored from Antioch to Kerak. In short, Maria Comnena had no need to remarry and if she did, she did so voluntarily to the man of her choice. She chose Balian d'Ibelin.

At the time of their marriage, Balian was the younger son of a crusader, who had slowly worked his way up through loyal service to the rank of baron and then married an heiress, Helvis of Ramla (Balian's mother). Balian's elder brother had inherited the paternal and maternal lands and titles, and held three fiefs: Ibelin, Ramla and Mirabel. Of these, the joint barony of Ramla and Mirabel was the significantly more significant and lucrative. In short, Balian was a landless knight.

For a Dowager Queen and Byzantine Princess to choose a landless knight as her second husband was nothing short of scandalous -- if not unprecedented. Constance, Princess of Antioch had chosen the adventurer Reynald de Chatillon, and Sibylla, Princess of Jerusalem, would later choose the landless Guy de Lusignan. Nevertheless, as in the other two cases, the choice of a landless man underscores the fact that the lady was not marrying for wealth and status (both of which she already had) but rather from love.

Obviously, Balian's motives may well have been far more material -- at last at the time of the wedding. He certainly has left us no record of what he felt towards her, and none of his contemporaries commented on it either. Nevertheless, whether he loved her from the start or not, there is considerable evidence that he came to love her deeply.

First, although their own four children hardly count given the pressure to produce heirs, the fact that Balian is credited with having a powerful influence on Maria’s child by her first marriage, Isabella, is significant. Since Isabella was a princess and of higher rank (i.e. she had no need not take any note of him0, her respect for him suggests he had been a good surrogate father to her – something that is unlikely if he had not been close to Maria. The family was furthermore a close-knit family, in which all the children supported one another closely -- again something indicative of a good marriage, which provides children with a living example of love.

Second, and more dramatically, Balian did not abandon his wife to her fate (as most of his contemporaries did) after the defeat at Hattin. Instead, he took the unprecedented step of requesting a safe-conduct from Saladin to remove her from Jerusalem before the impending siege could begin. Such a step took an unusual kind of courage and commitment since the defenses of the kingdom were shattered and Saladin held all the cards. It was also very risky: first going to Saladin, and then crossing Saracen-held territory unarmed.

Third, after the surrender of Jerusalem, Balian rejoined his wife and they worked together to regain some of what had been lost -- so much so that hostile chroniclers describe them as a team, alike to one another. They certainly are described working together to secure an annulment of Isabella's marriage to Humphrey of Toron. Cooperative work is, in my eyes, likewise a mark of a good marriage.

Last but not least, it seems unlikely that Maria, who had a choice, would have remained so loyal to a man beneath her station, if she had not felt loved. It is one thing to marry in infatuated haste, but had Balian proved an indifferent much less an unpleasant spouse as the years went by, Maria could have withdraw to her estates or all the way to Constantinople. She did not. Instead, she stayed with Balian through the worst years of defeat and desperation.

Maria and Balian are the central characters, and their loving relationship a key feature, of all three novels of the Jerusalem Trilogy:

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on September 25, 2016 05:00

September 23, 2016

My Responsibility as a Writer: Realistic, Human Characters

Nothing is more important to a novel than good characters. The theme may be visionary, the descriptions exquisite and the plot breath-taking, but without good characters it “ain’t good fiction.” Period.

The hero of my "Leonidas Trilogy": Leonidas of Sparta

The hero of my "Leonidas Trilogy": Leonidas of Sparta Nor can we, writers, really create characters – not good ones. We can create cartoons that stiffly toddle across the pages of our book, or we can cut-and-paste from other works, or even use pre-fab creations that everyone instantly recognizes: the beautiful seductress, the clever detective, the sensitive misunderstood child, the evil step-mother etc. etc. But the author who relies on these will never write good fiction.

Brad Pitt's Achilles transformed the Greek hero from a comic figure to a human.

Brad Pitt's Achilles transformed the Greek hero from a comic figure to a human. Good fiction requires good characters and good characters are as complex as human beings. Of course, only God can create humans, and writers are not God. We are at best disciples and prophets, interpreting God’s word, describing his creations – inadequately. But the better we are at understanding humans, the better we will be at describing them. And the better we describe them as unique individuals, the better will be our novel.

The hero of my Jerusalem trilogy is a baron of the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: Balian d'Ibelin

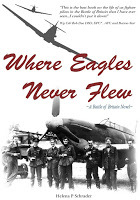

And just as humans grow-up, make mistakes, learn from their mistakes (or fail to do so), good characters are neither perfect nor stagnant. Good characters have flaws, and good characters change in the course of a novel. Only ancillary characters should be essentially the same at the end of a novel as they were at the beginning. While this is most pronounced in novels spanning a longer period of time (like my biographical novels), it should be true even of a novel covering only a few months, days or hours – because those few months/weeks/days/hours must represent a significant event for the central characters or the novel has no credible plot. My Battle of Britain novel, for example, only covers the months of May to September 1940, but for the characters it a pivotal period. Another novel could describe no more than the day September 11, 2001 – but it would only be a good novel about that day, if the key characters are different in a significant way at the end of it.

The pilots on the cover are "B" Flight 85 Squadron -- some of the real heroes of the Battle of BritainAnd good characters – really good characters – will never leave you in complete control of the plot. They will take the bit in their teeth now and again, and run away with you. When your characters do that, when they start shaping the novel for you, you know you have a good cast of characters. From then on, your job becomes one of directing and coaching rather than dictating. It is always a wonderful moment!

The pilots on the cover are "B" Flight 85 Squadron -- some of the real heroes of the Battle of BritainAnd good characters – really good characters – will never leave you in complete control of the plot. They will take the bit in their teeth now and again, and run away with you. When your characters do that, when they start shaping the novel for you, you know you have a good cast of characters. From then on, your job becomes one of directing and coaching rather than dictating. It is always a wonderful moment!  Three key characters of the book are on this cover: Richard the Lionheart (left), Saladin (right) and Balian d'Ibelin in the center. Today's blog is part of a Rave Review Book Club event featuring different author's ideas of their role as an author. If you are interested in joining this fun and supportive network of authors please check out our website at: Rave Review Book Club.

Three key characters of the book are on this cover: Richard the Lionheart (left), Saladin (right) and Balian d'Ibelin in the center. Today's blog is part of a Rave Review Book Club event featuring different author's ideas of their role as an author. If you are interested in joining this fun and supportive network of authors please check out our website at: Rave Review Book Club.

Published on September 23, 2016 01:15

September 18, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Prowess

Prowess or physical courage is probably the most ancient of all manly virtues; one need only think of Achilles and Hector. It was admired in men long before and long after the Age of Chivalry, and it is deemed the prime adornment and most important asset of men in nearly every culture from the native American indians to Japan and from the Norsemen to the highlands of Ethiopia. The romances of the age could be summarized as tales of "brave knights and fair ladies."

Balian’s courage is one of the few chivalrous virtues for which we have ample evidence. Even the Arab sources mention his military prowess, starting with the Battle of Montgisard. He is also credited with fighting his way out of the encirclement at Hattin – according to some interpretations with Raymond of Tripoli, according to others breaking out in the other direction. At all events, he fought his way out after hours of being in the thick of the grueling engagement. When he took command of the defenses of Jerusalem, he did not remain behind the walls, but first conducted dangerous foraging sorties into the surrounding area controlled by the enemy in order to capture necessary food supplies. After the siege began, he led a nearly suicidal assault on the Saracen camp. Balian d’Ibelin had physical (as well as moral) courage in abundance.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on September 18, 2016 02:00

September 11, 2016

Chivalry and Balian d'Ibelin: Righteousness

Righteousness in the context of the chivalry can best be described as a strong sense of right and wrong. It is about having a conscience and following it. On one level, morality was of course defined by Christianity, but in the highly legalistic societies of Western Europe it was also about "justice." Nobles and knights were the king's deputies and the executors of his justice. As such, knights were expected to enforce the law, contribute to the maintenance of law and order, and ensure justice in the abstract by recognizing and acting upon what was right and opposing that which was wrong/unjust -- even in the absence of specific laws and customs.

While it is hard to know the motives for actions, we can say with certainty that there is no recorded incident in which Balian d'Ibelin is known to have acted from base motives. He did not break treaties as Reynald de Chatillon did, nor did he usurp a crown as Guy de Lusignan did. He treated with Saladin as a devout Christian, never pretending (as Reginald de Sidon and Raymond de Tripoli allegedly did) that he wanted to convert. More important, there is positive evidence of Balian d'Ibelin's righteousness: first, his decision to take command of the defense of Jerusalem in 1187, and second the Treaty of Ramla.

In 1187, when Balian d'Ibelin came to Jerusalem on a safe-conduct from Saladin to remove his family to the comparative safety of Tyre, he could have chosen to stick to the letter of his agreement with Saladin. He could have remained only a single night and left the next day with his wife, children and household. He could have abandoned a city of roughly 20,000 inhabitants flooded with a further 60,000 refugees but without significant numbers of fighting men to the avowed vengeance of Saladin. That he instead agreed to take command of a hopeless defense -- although this meant that his own wife and children were put at risk -- strongly suggests that his sense of responsibility to others outweighed his personal desires. Perhaps that isn't the same thing as righteousness, but I think it is fair to equate the two. Balian had a choice and he chose not to do what was in his personal interest, but rather in the interest of others.

Again, when negotiating the Treaty of Ramla that ended the Third Crusade, Balian placed the interests of the majority of inhabitants ahead of his personal interests. In August 1192 Richard of England was determined to return to the West and the French were no longer taking orders from Richard in any case. In short, the crusade was disintegrating. Although Saladin's troops were tired and demoralized, the Sultan still held the better cards. Convincing him to sign a truce was certainly a diplomatic coup, and it is significant that Balian did not endanger the desperately-needed pause in the fighting by trying to regain his own barony of Ibelin -- although it was just 13 miles south of Jaffa, which Saladin granted to the Christians. The temptation to try to include it must have been almost unbearable, but rather than risk the peace Balian surrendered his own inheritance and source of wealth.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on September 11, 2016 05:00

September 4, 2016

Chivarly and Balian d'Ibelin: Loyalty

In the medieval context, the concept of loyalty was interpreted primarily as hierarchical loyalty to one's lord: a vassal to his liege, a servant to his master, a son to his father, a wife to her husband. While not unconditional and (as I have noted elsewhere) based on reciprocal obligations, medieval loyalty was nevertheless more comprehensive and consuming than modern notions. Loyalty was expected "unto death" with very few exceptions. Collateral loyalty -- to siblings, comrades, companions and compatriots -- was more similar to what we know today, i.e. was more voluntary and less binding. However, for a tenant-in-chief to the crown, as Ibelin was, the defining loyalty was that to the king.

The test of Balian d'Ibelin's loyalty to the crown came after the death of Baldwin V of Jerusalem; up to that time he like the bulk of his contemporaries was steadfastly loyal to the kings of Jerusalem. On the death of the child-king Baldwin V, Sibylla, the eldest of the two surviving children of King Amalric I and mother of Baldwin V, was the most obvious candidate to succeed to the throne. Unfortunately, she was married to a man who had lost the trust and respect of almost the entire High Court of Jerusalem. To gain support for her coronation, Sibylla promised to divorce the mistrusted Guy on the condition that she be allowed to marry the man of her choosing thereafter. Her supporters agreed to this condition, only for her to betray them by naming Guy de Lusignan as the man of her choice. With the help of the Patriarch and the Grand Master of the Knights Templar, she had herself crowned Queen of Jerusalem in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and then crowned Guy as her consort.

The problem was that the constitution of Jerusalem gave to the High Court of Jerusalem the prerogative of electing the monarch, and Sibylla had by-passed the High Court. Without the consent of the High Court, she and Guy were usurpers. The High Court attempted to crown her younger sister instead of her, only to be betrayed by her sister's husband. who refused to play the role of consort to his wife. At this point the opposition of most of the barons collapsed, and Guy and Sibylla were recognized as de facto King and Queen.

Two barons, however, refused to accept the usurpation. One was Raymond of Tripoli, who promptly signed a separate peace with Saladin. The other was Baldwin d'Ibelin, Balian's older brother. The elder Ibelin renounced his two baronies in favor of his son, turned this infant son over to the keeping of his younger brother and left the kingdom voluntarily. Balian, in contrast, placed the interests of the kingdom over his personal pride; he took the oath of fealty to the hated Guy de Lusignan. Not only that, but he was one of the intermediaries sent to reconcile Tripoli with Lusignan, and after the death of two of the others, the main spokesman.

An even greater indication of his loyalty was that despite his reservations about Guy de Lusignan's leadership, he dutifully mustered his feudal levees and his knights when Guy summoned them less than a year later. Most significantly, when Guy overrode the advice of his barons and ordered the advance on Tiberias, Ibelin commanded the rear-guard of the Christian army that marched -- against his better judgement -- to destruction on the Horns of Hattin.

It was not until after the death of Sibylla of Jerusalem, when Lusignan lost his last shadow of a claim to the throne, that Balian abandoned Lusignan. Following Sibylla's death, Ibelin's loyalty turned to the last remaining blood descendant of the royal family, the only surviving child of King Amalric, Isabella. But Balian's loyalty to Isabella was not mindless or blind. Because she was married to a man incapable of defending the kingdom, Ibelin led the faction of barons that insisted Isabella be separated from her ineffectual (and allegedly effeminate) husband before taking an oath to her. Only after she had been divorced from Humphrey de Toron and married to Conrad de Montferrat did the barons of Jerusalem, including Balian d'Ibelin, take an oath of fealty to her. Ibelin remained loyal to this oath despite Richard the Lionheart's fierce and tenacious support for Guy de Lusignan.

Buy now! Buy now! Buy now!

Published on September 04, 2016 04:33