Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 33

September 28, 2018

Rebels against Tyranny - To Displease an Emperor

Medieval women were far from powerless, but they generally find less place in the chroniclers than male relatives. Eschiva de Montbeliard was one such woman whose influence was almost certainly greater than the naked facts left in the historical record imply. I chose to make her the principal female protagonist in my series on the civil war in Outremer, and I chose to make her a lady-in-waiting to Queen Yolanda to incorporate more of Yolanda's own story.

Following the death of Queen Yolanda, Eschiva finds herself imprisoned in the Emperor's harem.

The Holy Roman Emperor had entered his wife’s apartment so silently that Eschiva had not realized he was here until he was glowering over her and hissed: “How dare you?” His voice was almost inaudible from chocking fury.

The Holy Roman Emperor had entered his wife’s apartment so silently that Eschiva had not realized he was here until he was glowering over her and hissed: “How dare you?” His voice was almost inaudible from chocking fury.

“How dare I what, my lo—your magnificence?” She stammered out. She could hardly hear her own words over the sound of her heart hammering in her ears.

Frederick answered by flinging her letter in her face, the seal broken and the parchment unfolded. “How dare you go behind my back!”

“I—I—” The fruit lady. She had betrayed her. Apparently, the woman had guessed the letter was in some way surreptitious, and surmised she could sell it to someone in the palace—maybe just Omar, who took it directly to Frederick. “I—didn’t mean to—to—I just—”

Frederick lashed out hard and fast, slapping her face so forcefully that it whipped her head to the side and left her neck aching as well as her cheek burning. “You are a liar as well as a deceitful bitch! We have tolerated your arrogance, impudence, and pride for the sake of our consort, but we will tolerate it no longer! We warned you not to mistake your position, but you are evidently too stupid to understand hints. We will speak plainly: you are in our power and we will dispose of you as we please. Don’t flatter yourself that it would please us to lie with you! You are too cold, boring and plain to arouse our interest! But we expect your brother to support us generously on our crusade, and he will assuredly do that more willingly if he thereby secures your, shall we say, well-being? If you ever, ever cross us again—much less write drivel as is in that scrap,” he gestured toward the letter on the floor between them, “we will give your brother a good reason to pay a fortune for your freedom.”

Their eyes were locked. His were like a serpent’s, burning her with his contempt and yet by their very intensity making her afraid to break eye contact. In those eyes was the promise of punishment, of pain and humiliation. He hated her, she registered with surprise. It surprised her because she was so far beneath him that she thought he took no note of her at all. She had been nothing but a witness, a silent witness, to all he had done to Yolanda. But maybe that was enough to make him hate her? Maybe she reminded him of his own injustice? Or did he hate her simply because he sensed her hatred of him? Whatever his reason, his hatred was very, very dangerous.

Eschiva crumpled into a deep curtsy, and managed to squeak out, “You will have no reason for complaint, your magnificence.” Eschiva spoke to her discarded letter and the toes of his black shoes. Frederick turned on heel and stalked out, slamming the door behind him.

Only very slowly did Eschiva unbend, pushing herself upright again. No terror she had ever known before equaled what she felt now. This threat, this hint of dark dungeons, pillories, floggings or starvation, was terrifying precisely because it was so vague. It was open-ended and unfathomable. Hadn’t he heated an iron crown to a glowing red and then nailed it to the head of a defeated enemy?

He was not a man of mercy, Yolanda had remarked once. Just that: not a man of mercy. Another time she had complained, “He is vindictive. He bears a grudge forever, but in silence and hidden under sweet words—until he chooses to take his revenge.”

Eschiva discovered to her surprise that she was still clinging to the Odyssey. Indeed, she was clinging to it so firmly that her fingers were hurting. She forced them to relax, but she hugged the book to her chest. It was a memory, a talisman, from a better time and place. From home.

She started. The Odyssey. Ulysses had been driven off course, endured horrible and wonderful adventures, lost all his companions, but in the end, he returned home. And there was a ship in the harbor at this very moment, which would soon set sail for Cyprus. A ship on which her cousin, stranger though he was, would sail. She had thought to send a message by him, but since that had failed, somehow, somehow—Mary have mercy on me!—somehow, Eschiva told herself, she had to be aboard that ship herself.

She didn’t have a moment to lose. The funeral was over. Her cousin would undoubtedly sail with the morning tide, anxious to bring word to Yolanda’s vassals and subjects that she was dead. Good God! The High Court of Jerusalem would need to elect a baillie for Yolanda’s infant son Conrad.

Eschiva started pacing the little chamber in an effort to calm her nerves and stimulate her brain. Like a captive lion, she moved back-and-forth on silent feet, her eyes searching and searching for something. She stopped. She was staring at Yolanda’s dressing table. On it was the little glass bottle with the sleeping powder the Jewish doctor had given her. “Use only a very little,” he had warned. “No more than a pinch in a glass of wine. It is very powerful. Too much, and you will sleep like the dead. A little more, and you will be dead.”

She had to get some of that powder into something Omar drank.

Of course! The wine!

Omar was Muslim, but he had a weakness for wine. To maintain his image and authority among his co-religionists, he publicly abhorred and condemned wine. He drank in secret. In the Queen’s anteroom. Because no one dared follow him inside, and the harem girls did not enter the Queen’s apartment either, it was the perfect place. Yolanda had encouraged him in this vice, because, of course, she used it as a means to coerce him into little favors. “If you don’t do this, I’ll tell the Imam that you drink….” He had had no wine since Yolanda died.

Eschiva nodded to herself, confident that she could invite him in and give him wine with a hefty dose of the sleeping powder already mixed in. She would then retreat to the bedchamber and loudly lock the door from the inside as if she wanted nothing to do with him. When he was asleep, she would be able to come out, remove the keys to the outer door, leave the harem, and bolt it from the outside. No one would suspect anything was amiss until the next morning when Ahmed came to bring Omar his breakfast as he washed, changed and prayed. BUY NOW!For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

BUY NOW!For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Following the death of Queen Yolanda, Eschiva finds herself imprisoned in the Emperor's harem.

The Holy Roman Emperor had entered his wife’s apartment so silently that Eschiva had not realized he was here until he was glowering over her and hissed: “How dare you?” His voice was almost inaudible from chocking fury.

The Holy Roman Emperor had entered his wife’s apartment so silently that Eschiva had not realized he was here until he was glowering over her and hissed: “How dare you?” His voice was almost inaudible from chocking fury.“How dare I what, my lo—your magnificence?” She stammered out. She could hardly hear her own words over the sound of her heart hammering in her ears.

Frederick answered by flinging her letter in her face, the seal broken and the parchment unfolded. “How dare you go behind my back!”

“I—I—” The fruit lady. She had betrayed her. Apparently, the woman had guessed the letter was in some way surreptitious, and surmised she could sell it to someone in the palace—maybe just Omar, who took it directly to Frederick. “I—didn’t mean to—to—I just—”

Frederick lashed out hard and fast, slapping her face so forcefully that it whipped her head to the side and left her neck aching as well as her cheek burning. “You are a liar as well as a deceitful bitch! We have tolerated your arrogance, impudence, and pride for the sake of our consort, but we will tolerate it no longer! We warned you not to mistake your position, but you are evidently too stupid to understand hints. We will speak plainly: you are in our power and we will dispose of you as we please. Don’t flatter yourself that it would please us to lie with you! You are too cold, boring and plain to arouse our interest! But we expect your brother to support us generously on our crusade, and he will assuredly do that more willingly if he thereby secures your, shall we say, well-being? If you ever, ever cross us again—much less write drivel as is in that scrap,” he gestured toward the letter on the floor between them, “we will give your brother a good reason to pay a fortune for your freedom.”

Their eyes were locked. His were like a serpent’s, burning her with his contempt and yet by their very intensity making her afraid to break eye contact. In those eyes was the promise of punishment, of pain and humiliation. He hated her, she registered with surprise. It surprised her because she was so far beneath him that she thought he took no note of her at all. She had been nothing but a witness, a silent witness, to all he had done to Yolanda. But maybe that was enough to make him hate her? Maybe she reminded him of his own injustice? Or did he hate her simply because he sensed her hatred of him? Whatever his reason, his hatred was very, very dangerous.

Eschiva crumpled into a deep curtsy, and managed to squeak out, “You will have no reason for complaint, your magnificence.” Eschiva spoke to her discarded letter and the toes of his black shoes. Frederick turned on heel and stalked out, slamming the door behind him.

Only very slowly did Eschiva unbend, pushing herself upright again. No terror she had ever known before equaled what she felt now. This threat, this hint of dark dungeons, pillories, floggings or starvation, was terrifying precisely because it was so vague. It was open-ended and unfathomable. Hadn’t he heated an iron crown to a glowing red and then nailed it to the head of a defeated enemy?

He was not a man of mercy, Yolanda had remarked once. Just that: not a man of mercy. Another time she had complained, “He is vindictive. He bears a grudge forever, but in silence and hidden under sweet words—until he chooses to take his revenge.”

Eschiva discovered to her surprise that she was still clinging to the Odyssey. Indeed, she was clinging to it so firmly that her fingers were hurting. She forced them to relax, but she hugged the book to her chest. It was a memory, a talisman, from a better time and place. From home.

She started. The Odyssey. Ulysses had been driven off course, endured horrible and wonderful adventures, lost all his companions, but in the end, he returned home. And there was a ship in the harbor at this very moment, which would soon set sail for Cyprus. A ship on which her cousin, stranger though he was, would sail. She had thought to send a message by him, but since that had failed, somehow, somehow—Mary have mercy on me!—somehow, Eschiva told herself, she had to be aboard that ship herself.

She didn’t have a moment to lose. The funeral was over. Her cousin would undoubtedly sail with the morning tide, anxious to bring word to Yolanda’s vassals and subjects that she was dead. Good God! The High Court of Jerusalem would need to elect a baillie for Yolanda’s infant son Conrad.

Eschiva started pacing the little chamber in an effort to calm her nerves and stimulate her brain. Like a captive lion, she moved back-and-forth on silent feet, her eyes searching and searching for something. She stopped. She was staring at Yolanda’s dressing table. On it was the little glass bottle with the sleeping powder the Jewish doctor had given her. “Use only a very little,” he had warned. “No more than a pinch in a glass of wine. It is very powerful. Too much, and you will sleep like the dead. A little more, and you will be dead.”

She had to get some of that powder into something Omar drank.

Of course! The wine!

Omar was Muslim, but he had a weakness for wine. To maintain his image and authority among his co-religionists, he publicly abhorred and condemned wine. He drank in secret. In the Queen’s anteroom. Because no one dared follow him inside, and the harem girls did not enter the Queen’s apartment either, it was the perfect place. Yolanda had encouraged him in this vice, because, of course, she used it as a means to coerce him into little favors. “If you don’t do this, I’ll tell the Imam that you drink….” He had had no wine since Yolanda died.

Eschiva nodded to herself, confident that she could invite him in and give him wine with a hefty dose of the sleeping powder already mixed in. She would then retreat to the bedchamber and loudly lock the door from the inside as if she wanted nothing to do with him. When he was asleep, she would be able to come out, remove the keys to the outer door, leave the harem, and bolt it from the outside. No one would suspect anything was amiss until the next morning when Ahmed came to bring Omar his breakfast as he washed, changed and prayed.

BUY NOW!For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

BUY NOW!For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on September 28, 2018 02:00

September 21, 2018

Threats to a Boy King - An Excerpt from Rebels against Tyranny

In the civil war between the barons of Outremer and the Holy Roman Emperor, the King of Cyprus supported the barons and freed himself of Imperial overlordship -- but only at the end of the long struggle. When the civil war began, Henry was still a child and a vulnerable pawn.

In this scene, eight-year-old Henry has just been crowned king and, exhausted, he is retiring for bed when a harbinger of the conflict to come breaks in on his happy world.

Henry hastened to break off another piece of marzipan, while his nurse went into the bedchamber to pour the water into a glazed bowl and lay out his washcloth and the boar-hair toothbrush. The knock at the door startled him, and he said, “Come in!” without thinking. Henry was in his own palace and had not learned fear. With all his nobles, bishops and foreign diplomats at the banquet, however, he hadn’t expected anyone to disturb him.

Henry hastened to break off another piece of marzipan, while his nurse went into the bedchamber to pour the water into a glazed bowl and lay out his washcloth and the boar-hair toothbrush. The knock at the door startled him, and he said, “Come in!” without thinking. Henry was in his own palace and had not learned fear. With all his nobles, bishops and foreign diplomats at the banquet, however, he hadn’t expected anyone to disturb him. The door opened and a strange man entered. Although he was dressed like a high nobleman in velvet robes with wide bands of embroidery, he was slight of stature, with sharp features, receding hairline, and a smile that made Henry’s skin creep.

“Sir!” The nurse, coming from the bedchamber, exclaimed, astonished by the intrusion of a stranger on the king when he was almost ready for bed.

“Go away, woman!” The man dismissed her irritably. “I am Sir Amaury Barlais, and I bring a letter to the king from his mother, Queen Alice of Champagne.”

At the mention of his mother, Henry’s fear receded and he eagerly held out his hands. “Oh, that’s wonderful! Give it to me!”

Barlais did not comply, but staring at the Greek serving woman ordered a second time. “Leave us, woman! I come directly from the Queen Mother!”

The nurse looked in alarm at her charge, at the intruder, and then back to Henry for guidance.

“She’s my nurse, why can’t she stay?” Henry asked Barlais.

Barlais started, and then with a smile conceded. “You’re right, my lord. Why not? But I am ever so thirsty and I’m sure you must be too after all that marzipan.” He glanced at the diminished marzipan crown. “Would you be so kind as to fetch us wine, woman?”

The nurse was of humble birth and she knew her place. She did not speak very much French, her language with Henry being her native Greek. She did not have any interest in politics and did not know the names of most of Henry’s vassals. Her world revolved around keeping Henry happy and healthy, making sure he ate, washed and said his prayers. She did not know who Sir Amaury Barlais was, nor whether it was credible that he had a letter from the Queen Mother. It seemed odd, however, that he came now as if he had been lurking in wait for Lady Alys to leave the chamber. Her maternal instincts screamed that this man meant Henry harm, but what was a Greek peasant woman supposed to say to a Frankish lord when he asked for wine?

She bobbed a curtsey and darted out the door. Outside she started running down the corridor. Her mind was fixed on one thing: she had to fetch Lady Alys immediately. Henry was in danger, even if the man had not been armed—or didn’t appear to be. He might, she realized in horror, have a dagger hidden somewhere in the skirts or sleeves of his fine robes. Or he might have poison. Or maybe he had come to kidnap Henry, and hold him for ransom? She had heard tell that the old king, Henry’s father, had been seized by pirates when he was a little boy and taken to the land of the Armenians.

Henry’s nanny was not an old woman, but her life of luxury in the royal palace with a child king who loved sweets had made her fat. She was not used to running, and she was soon out of breath. Even as she gasped for breath, the thought of Henry alone with that man frightened her forward. She burst into the treasury, babbling in Greek, rendered incomprehensible by her breathlessness.

“Good heavens!” Lady Alys exclaimed, shocked and alarmed to have someone burst into the treasury when she was alone there. If it had been an armed man, she would have been utterly helpless to defend the royal treasure. As it was, the sight of the nurse set off other alarms. The woman was bright red, panting, sweating and wailing in Greek, “Come quick, come quick! Man with Henry! Bad man! Hurry! Hurry!”

Lady Alys barely took the time to close the lock on the chest before she followed the nanny out the door. She took a step before remembering to return and turn the key in the door of the treasury. She replaced the key on the ring tied to her belt, and the keys jingled and clacked as she hastened down the hall. Although the king’s apartments were only on the far side of the interior courtyard, it seemed to take forever for the two women to reach the royal suite. The nanny was so out of breath she could not keep up with Lady Alys, and the wife of the baillie burst into the king’s apartment alone exclaiming, “My lord king! Sir!”

The room was empty.

“Henry?”

No answer.

Lady Alys stood stalk still inside the door, her eyes scanning the room before her. The marzipan subtlety stood on the table, the broken crown still held up by the various animals of the king’s menagerie. Nothing seemed amiss, and there was not a soul in the room. She looked toward the adjoining bedchamber, and her heart missed a beat. The bed covers had been torn off and tossed on the floor. She moved cautiously forward. “Henry?”

The covers shrugged and a sob reached her ears. Alys ran to the bed and pulled back the sheets to find King Henry curled up with his hands over his face.

“Henry? What’s happened? What’s wrong?”

Henry came into her arms at once and he turned his tear-covered face into her breast, but he didn’t say anything articulate. Lady Alys folded her arms around her eight-year-old king and held him as his nanny hobbled breathlessly into the room and sat on the bed beside her.

“What’s happened, pet?” The nanny asked in Greek, stroking Henry’s shoulder.

“Sir Amaury,” Henry gasped out at last.

“Which Sir Amaury?” Lady Alys asked.

“Barlais,” Henry answered between sobs, and Lady Alys stiffened at once. “He—he said—he had—a letter—from my mother!” Lady Alys was holding her breath, remembering all the rumors from years ago of Barlais’ affair with the Queen Mother. If he had gotten to her…. If he had managed to sweet-talk her….

“But—it wasn’t even for me!” Henry broke down into miserable sobs again, and Lady Alys held him closer, while his nanny clucked and cooed to him sympathetically. Why the boy should care this much about the worthless bitch who had borne him, Lady Alys would never know. The Queen Mother had never taken much interest in him, and six months ago she’d abandoned him with hardly a farewell to marry Bohemond of Antioch.

Henry suddenly drew back so he could look her in the face, his own face red, puffy, and wet from crying. “It was a letter from my mother naming Barlais as my baillie!” Henry wailed. “He says he’s—he’s in charge now—and I have to do whatever he says! I don’t like him, Lady Alys!” Henry declared with the simplicity of childhood. “I don’t like him. I don’t want to do what he says! I want Lord Philip to be my baillie like he’s always been!”

Lady Alys pulled Henry back into her arms and stroked his back. “That’s what Lord Philip wants too, Henry. We will have to look into this.”

Henry had pulled away again to speak to her, his eyes fixed on hers and a frown furrowing his forehead. “But Barlais says my mother is my regent and she appoints my baillie and he had a paper to prove it. He had a letter with my mother’s seal and he showed it to me. It named him my baillie!”

“We’ll see about that, Henry. It’s true your mother is your regent, but she named Lord Philip your baillie. The entire High Court took an oath to obey him until you came of age. You may have been crowned today, but you haven’t come of age yet. I’m quite sure the High Court will have something to say about this.”

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on September 21, 2018 02:00

Rebels against Tyranny - Threats to a Boy King

In the civil war between the barons of Outremer and the Holy Roman Emperor, the King of Cyprus supported the barons and freed himself of Imperial overlordship -- but only at the end of the long struggle. When the civil war began, Henry was still a child and a vulnerable pawn.

In this scene, eight-year-old Henry has just been crowned king and, exhausted, he is retiring for bed when a harbinger of the conflict to come breaks in on his happy world.

Henry hastened to break off another piece of marzipan, while his nurse went into the bedchamber to pour the water into a glazed bowl and lay out his washcloth and the boar-hair toothbrush. The knock at the door startled him, and he said, “Come in!” without thinking. Henry was in his own palace and had not learned fear. With all his nobles, bishops and foreign diplomats at the banquet, however, he hadn’t expected anyone to disturb him.

Henry hastened to break off another piece of marzipan, while his nurse went into the bedchamber to pour the water into a glazed bowl and lay out his washcloth and the boar-hair toothbrush. The knock at the door startled him, and he said, “Come in!” without thinking. Henry was in his own palace and had not learned fear. With all his nobles, bishops and foreign diplomats at the banquet, however, he hadn’t expected anyone to disturb him. The door opened and a strange man entered. Although he was dressed like a high nobleman in velvet robes with wide bands of embroidery, he was slight of stature, with sharp features, receding hairline, and a smile that made Henry’s skin creep.

“Sir!” The nurse, coming from the bedchamber, exclaimed, astonished by the intrusion of a stranger on the king when he was almost ready for bed.

“Go away, woman!” The man dismissed her irritably. “I am Sir Amaury Barlais, and I bring a letter to the king from his mother, Queen Alice of Champagne.”

At the mention of his mother, Henry’s fear receded and he eagerly held out his hands. “Oh, that’s wonderful! Give it to me!”

Barlais did not comply, but staring at the Greek serving woman ordered a second time. “Leave us, woman! I come directly from the Queen Mother!”

The nurse looked in alarm at her charge, at the intruder, and then back to Henry for guidance.

“She’s my nurse, why can’t she stay?” Henry asked Barlais.

Barlais started, and then with a smile conceded. “You’re right, my lord. Why not? But I am ever so thirsty and I’m sure you must be too after all that marzipan.” He glanced at the diminished marzipan crown. “Would you be so kind as to fetch us wine, woman?”

The nurse was of humble birth and she knew her place. She did not speak very much French, her language with Henry being her native Greek. She did not have any interest in politics and did not know the names of most of Henry’s vassals. Her world revolved around keeping Henry happy and healthy, making sure he ate, washed and said his prayers. She did not know who Sir Amaury Barlais was, nor whether it was credible that he had a letter from the Queen Mother. It seemed odd, however, that he came now as if he had been lurking in wait for Lady Alys to leave the chamber. Her maternal instincts screamed that this man meant Henry harm, but what was a Greek peasant woman supposed to say to a Frankish lord when he asked for wine?

She bobbed a curtsey and darted out the door. Outside she started running down the corridor. Her mind was fixed on one thing: she had to fetch Lady Alys immediately. Henry was in danger, even if the man had not been armed—or didn’t appear to be. He might, she realized in horror, have a dagger hidden somewhere in the skirts or sleeves of his fine robes. Or he might have poison. Or maybe he had come to kidnap Henry, and hold him for ransom? She had heard tell that the old king, Henry’s father, had been seized by pirates when he was a little boy and taken to the land of the Armenians.

Henry’s nanny was not an old woman, but her life of luxury in the royal palace with a child king who loved sweets had made her fat. She was not used to running, and she was soon out of breath. Even as she gasped for breath, the thought of Henry alone with that man frightened her forward. She burst into the treasury, babbling in Greek, rendered incomprehensible by her breathlessness.

“Good heavens!” Lady Alys exclaimed, shocked and alarmed to have someone burst into the treasury when she was alone there. If it had been an armed man, she would have been utterly helpless to defend the royal treasure. As it was, the sight of the nurse set off other alarms. The woman was bright red, panting, sweating and wailing in Greek, “Come quick, come quick! Man with Henry! Bad man! Hurry! Hurry!”

Lady Alys barely took the time to close the lock on the chest before she followed the nanny out the door. She took a step before remembering to return and turn the key in the door of the treasury. She replaced the key on the ring tied to her belt, and the keys jingled and clacked as she hastened down the hall. Although the king’s apartments were only on the far side of the interior courtyard, it seemed to take forever for the two women to reach the royal suite. The nanny was so out of breath she could not keep up with Lady Alys, and the wife of the baillie burst into the king’s apartment alone exclaiming, “My lord king! Sir!”

The room was empty.

“Henry?”

No answer.

Lady Alys stood stalk still inside the door, her eyes scanning the room before her. The marzipan subtlety stood on the table, the broken crown still held up by the various animals of the king’s menagerie. Nothing seemed amiss, and there was not a soul in the room. She looked toward the adjoining bedchamber, and her heart missed a beat. The bed covers had been torn off and tossed on the floor. She moved cautiously forward. “Henry?”

The covers shrugged and a sob reached her ears. Alys ran to the bed and pulled back the sheets to find King Henry curled up with his hands over his face.

“Henry? What’s happened? What’s wrong?”

Henry came into her arms at once and he turned his tear-covered face into her breast, but he didn’t say anything articulate. Lady Alys folded her arms around her eight-year-old king and held him as his nanny hobbled breathlessly into the room and sat on the bed beside her.

“What’s happened, pet?” The nanny asked in Greek, stroking Henry’s shoulder.

“Sir Amaury,” Henry gasped out at last.

“Which Sir Amaury?” Lady Alys asked.

“Barlais,” Henry answered between sobs, and Lady Alys stiffened at once. “He—he said—he had—a letter—from my mother!” Lady Alys was holding her breath, remembering all the rumors from years ago of Barlais’ affair with the Queen Mother. If he had gotten to her…. If he had managed to sweet-talk her….

“But—it wasn’t even for me!” Henry broke down into miserable sobs again, and Lady Alys held him closer, while his nanny clucked and cooed to him sympathetically. Why the boy should care this much about the worthless bitch who had borne him, Lady Alys would never know. The Queen Mother had never taken much interest in him, and six months ago she’d abandoned him with hardly a farewell to marry Bohemond of Antioch.

Henry suddenly drew back so he could look her in the face, his own face red, puffy, and wet from crying. “It was a letter from my mother naming Barlais as my baillie!” Henry wailed. “He says he’s—he’s in charge now—and I have to do whatever he says! I don’t like him, Lady Alys!” Henry declared with the simplicity of childhood. “I don’t like him. I don’t want to do what he says! I want Lord Philip to be my baillie like he’s always been!”

Lady Alys pulled Henry back into her arms and stroked his back. “That’s what Lord Philip wants too, Henry. We will have to look into this.”

Henry had pulled away again to speak to her, his eyes fixed on hers and a frown furrowing his forehead. “But Barlais says my mother is my regent and she appoints my baillie and he had a paper to prove it. He had a letter with my mother’s seal and he showed it to me. It named him my baillie!”

“We’ll see about that, Henry. It’s true your mother is your regent, but she named Lord Philip your baillie. The entire High Court took an oath to obey him until you came of age. You may have been crowned today, but you haven’t come of age yet. I’m quite sure the High Court will have something to say about this.”

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on September 21, 2018 02:00

September 14, 2018

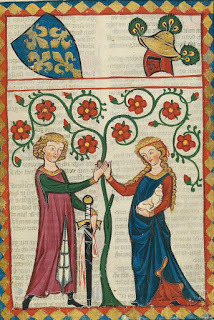

The Forgotten and Unloved Bride of an Emperor - Excerpt from Rebels against Tyranny

While the hostility between the Ibelins and Amaury Barlais aggravated the civil war in the crusader states, the root cause of the war lay in the marriage of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II Hohenstaufen, to the heiress of Jerusalem, Yolanda. Frederick II is a legendary monarch, famed for his success in holding onto power from the Baltic Sea to Sicily. He is often characterized as a monarch "ahead of his time," and admired for his learning. His struggles with the Lombard League, his own son, and his bitter conflict with the papacy are the subject of countless works of fiction and non-fiction. Yolanda, on the other hand, has largely been lost in the history books because she was an unloved second wife who died less than three years after her marriage to Frederick. I wanted to give her a face and voice -- if only for a brief moment.

Cheering from the city marked the progress of the queen toward the harbor. They all turned to watch and shortly afterward, the queen’s party emerged. Yolanda was riding on a very pretty, dish-faced white palfrey decked out in a saddlecloth with the arms of Jerusalem on it. She herself wore a practical russet gown, but over this, a surcoat of white silk “dusted” with gold crosses. Her head was encased in a white, gauze wimple to mark her status as a married woman, despite the fact she was still a maiden.

The cheering of her people made the girl-queen blush with embarrassment, but it also made her smile and wave. Beirut’s heart went out to her. She was still so very young. Indeed, she was the same age as his only daughter, Bella. He couldn’t have borne the thought of sending his little girl across the water to an utter stranger, and he found his dislike of John de Brienne hardening.

Despite the death of his wife, Brienne continued to claim the crown of Jerusalem, dubiously Beirut thought, because of Yolanda. Yet he hadn’t bothered to visit her in five years. And while Beirut recognized the advantages of Yolanda’s marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, he was also a father. He loved his six children more than his own life, and sometimes more than Jerusalem. Based on what he had heard, he would not have sent his daughter Bella to marry Frederick Hohenstaufen—not for all the gold in Constantinople.

Queen Yolanda approached, flanked on one side by Eudes de Montbéliard and on the other by a young woman Beirut did not recognize. “Who is the young lady with the Queen?” Beirut asked Sidon.

“Ah, that is Eudes’ sister Eschiva. The Queen asked her to join her household,” Sidon hastened to explain, anticipating Beirut’s objections to the “parvenu” Montbéliards again successfully positioning themselves close to the crown.

To Sidon’s surprise, Beirut nodded with approval. Now that they were nearer, he recognized the girl as the most sensible of all the maidens in attendance on the Queen over the past three weeks. He had noticed and approved of the way she had kept to the background while the other girls preened and flirted—all too often with his son Balian. More important, it had been this girl who repeatedly calmed or encouraged an uncertain and nervous Yolanda. He simply had not realized that she was Montbéliard’s daughter. Now that Sidon identified her, however, he noticed that she shared a family resemblance with her brother from the bright blond hair and blue eyes to the long face and nose. Unlike her brother, however, she smiled and chattered excitedly with the Queen. Like his son Hugh, she seemed delighted to be going West, something that would surely help the Queen overcome her obvious foreboding.

As the Queen reached the gangway to the Imperial dromond, she drew up. At once, a knight from her entourage sprang down to hold her off-stirrup. As she touched the ground, a groom came forward to lead her horse away. Meanwhile, the ship’s captain descended the gangway to bend his knee, his hand on his heart, before her. Beirut was glad she was traveling on an Imperial ship commanded by a Sicilian captain because there had been some very unseemly squabbling between the Pisans, Genoese and Venetian communities of Outremer about who should have the honor of transporting the Queen and her party.

Before the captain could lead Yolanda aboard his ship, however, Beirut stepped forward. “My lady queen!” Yolanda turned, startled, in the direction of his voice. She looked at Beirut uncertainly, unsure who he was.

“John d’Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, my lady.” Beirut helped her out of her dilemma, and she broke into a wide smile.

“Of course, my lord. I should have remembered you, but I’ve met so many new people these last few weeks.”

“I understand entirely, my lady. I have come to see you off, and give you a little gift—more for your voyage than your marriage.” As he spoke he gestured to his sons, and Balian at once opened his father’s saddlebag to remove an object wrapped in painted leather. He handed this to his father, and Beirut unwrapped the leader cover to withdraw a book. This he held out to Queen Yolanda.

Eschiva de Montbéliard had come to stand behind her queen. At the sight of the book, she let out a little gasp of delight.

Beirut cast the Montbéliard girl a smile before addressing the Queen again. “This was your great-grandmother’s book. She would have wanted you to have it.”

Queen Yolanda looked up at him frowning slightly as she tried to work it out. “My great-grandmother? Queen Maria Comnena? Your mother?” Yolanda might not have recognized him, but she had learned the lessons about her dynasty well.

“Exactly.” Beirut lovingly opened the ivory cover of the book to reveal the interior, eliciting another appreciative gasp from the Montbéliard girl. “It is, I am afraid, in Greek, but I was told you were taught Greek.” It was as much a question as a statement.

The Queen nodded vigorously, going on tip-toe to see the book better. Beirut at once lowered his hands to make it easier for her to see and explained. “It is the story of a Greek sailor trying to return home after a long war in what is now the Empire of Nicaea. Along the way, he suffers many adventures and hardships that take him all across the Mediterranean. Although the journey is embellished with many fanciful beasts and mythical adventures, still I think you will find it a lively and informative companion on your journey. At least I hope you do.” Beirut bowed deeply and handed the book to his Queen.

Yolanda took it from him and held it to her still flat chest. “It is very, very kind of you, my lord! I can’t wait to read it!” For an instant, she was a little girl again rather than a queen and bride.

Beirut bowed again. “I hope it will always bring you pleasure—and remind you of your home and your heritage.”

Yolanda seemed to want to say more, but Eudes de Montbéliard was moving from foot to foot to indicate his impatience. He cleared his throat and admonished, “We do not want to miss the tide, my lady.” He always managed to sound as if he thought he knew better than everyone else, Beirut thought.

Yolanda responded as if she had been guilty of some misdeed and hastened to do as Montbéliard urged. She started for the ship, but then she stopped to say over her shoulder with heartfelt emphasis, “Thank you again, my lord! I love books!”

Montbéliard shooed his queen and his sister aboard the ship, giving her no chance to stay on deck to watch them cast off. They are prisoners already, Beirut thought—not entirely logically. Yolanda was on her way to be crowned Holy Roman Empress—arguably the most powerful woman on earth. So why did he feel so sorry for her, and so sad?

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Cheering from the city marked the progress of the queen toward the harbor. They all turned to watch and shortly afterward, the queen’s party emerged. Yolanda was riding on a very pretty, dish-faced white palfrey decked out in a saddlecloth with the arms of Jerusalem on it. She herself wore a practical russet gown, but over this, a surcoat of white silk “dusted” with gold crosses. Her head was encased in a white, gauze wimple to mark her status as a married woman, despite the fact she was still a maiden.

The cheering of her people made the girl-queen blush with embarrassment, but it also made her smile and wave. Beirut’s heart went out to her. She was still so very young. Indeed, she was the same age as his only daughter, Bella. He couldn’t have borne the thought of sending his little girl across the water to an utter stranger, and he found his dislike of John de Brienne hardening.

Despite the death of his wife, Brienne continued to claim the crown of Jerusalem, dubiously Beirut thought, because of Yolanda. Yet he hadn’t bothered to visit her in five years. And while Beirut recognized the advantages of Yolanda’s marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, he was also a father. He loved his six children more than his own life, and sometimes more than Jerusalem. Based on what he had heard, he would not have sent his daughter Bella to marry Frederick Hohenstaufen—not for all the gold in Constantinople.

Queen Yolanda approached, flanked on one side by Eudes de Montbéliard and on the other by a young woman Beirut did not recognize. “Who is the young lady with the Queen?” Beirut asked Sidon.

“Ah, that is Eudes’ sister Eschiva. The Queen asked her to join her household,” Sidon hastened to explain, anticipating Beirut’s objections to the “parvenu” Montbéliards again successfully positioning themselves close to the crown.

To Sidon’s surprise, Beirut nodded with approval. Now that they were nearer, he recognized the girl as the most sensible of all the maidens in attendance on the Queen over the past three weeks. He had noticed and approved of the way she had kept to the background while the other girls preened and flirted—all too often with his son Balian. More important, it had been this girl who repeatedly calmed or encouraged an uncertain and nervous Yolanda. He simply had not realized that she was Montbéliard’s daughter. Now that Sidon identified her, however, he noticed that she shared a family resemblance with her brother from the bright blond hair and blue eyes to the long face and nose. Unlike her brother, however, she smiled and chattered excitedly with the Queen. Like his son Hugh, she seemed delighted to be going West, something that would surely help the Queen overcome her obvious foreboding.

As the Queen reached the gangway to the Imperial dromond, she drew up. At once, a knight from her entourage sprang down to hold her off-stirrup. As she touched the ground, a groom came forward to lead her horse away. Meanwhile, the ship’s captain descended the gangway to bend his knee, his hand on his heart, before her. Beirut was glad she was traveling on an Imperial ship commanded by a Sicilian captain because there had been some very unseemly squabbling between the Pisans, Genoese and Venetian communities of Outremer about who should have the honor of transporting the Queen and her party.

Before the captain could lead Yolanda aboard his ship, however, Beirut stepped forward. “My lady queen!” Yolanda turned, startled, in the direction of his voice. She looked at Beirut uncertainly, unsure who he was.

“John d’Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, my lady.” Beirut helped her out of her dilemma, and she broke into a wide smile.

“Of course, my lord. I should have remembered you, but I’ve met so many new people these last few weeks.”

“I understand entirely, my lady. I have come to see you off, and give you a little gift—more for your voyage than your marriage.” As he spoke he gestured to his sons, and Balian at once opened his father’s saddlebag to remove an object wrapped in painted leather. He handed this to his father, and Beirut unwrapped the leader cover to withdraw a book. This he held out to Queen Yolanda.

Eschiva de Montbéliard had come to stand behind her queen. At the sight of the book, she let out a little gasp of delight.

Beirut cast the Montbéliard girl a smile before addressing the Queen again. “This was your great-grandmother’s book. She would have wanted you to have it.”

Queen Yolanda looked up at him frowning slightly as she tried to work it out. “My great-grandmother? Queen Maria Comnena? Your mother?” Yolanda might not have recognized him, but she had learned the lessons about her dynasty well.

“Exactly.” Beirut lovingly opened the ivory cover of the book to reveal the interior, eliciting another appreciative gasp from the Montbéliard girl. “It is, I am afraid, in Greek, but I was told you were taught Greek.” It was as much a question as a statement.

The Queen nodded vigorously, going on tip-toe to see the book better. Beirut at once lowered his hands to make it easier for her to see and explained. “It is the story of a Greek sailor trying to return home after a long war in what is now the Empire of Nicaea. Along the way, he suffers many adventures and hardships that take him all across the Mediterranean. Although the journey is embellished with many fanciful beasts and mythical adventures, still I think you will find it a lively and informative companion on your journey. At least I hope you do.” Beirut bowed deeply and handed the book to his Queen.

Yolanda took it from him and held it to her still flat chest. “It is very, very kind of you, my lord! I can’t wait to read it!” For an instant, she was a little girl again rather than a queen and bride.

Beirut bowed again. “I hope it will always bring you pleasure—and remind you of your home and your heritage.”

Yolanda seemed to want to say more, but Eudes de Montbéliard was moving from foot to foot to indicate his impatience. He cleared his throat and admonished, “We do not want to miss the tide, my lady.” He always managed to sound as if he thought he knew better than everyone else, Beirut thought.

Yolanda responded as if she had been guilty of some misdeed and hastened to do as Montbéliard urged. She started for the ship, but then she stopped to say over her shoulder with heartfelt emphasis, “Thank you again, my lord! I love books!”

Montbéliard shooed his queen and his sister aboard the ship, giving her no chance to stay on deck to watch them cast off. They are prisoners already, Beirut thought—not entirely logically. Yolanda was on her way to be crowned Holy Roman Empress—arguably the most powerful woman on earth. So why did he feel so sorry for her, and so sad?

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on September 14, 2018 02:00

Rebels against Tyranny - The Forgotten and Unloved Bride of an Emperor

While the hostility between the Ibelins and Amaury Barlais aggravated the civil war in the crusader states, the root cause of the war lay in the marriage of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II Hohenstaufen, to the heiress of Jerusalem, Yolanda. Frederick II is a legendary monarch, famed for his success in holding onto power from the Baltic Sea to Sicily. He is often characterized as a monarch "ahead of his time," and admired for his learning. His struggles with the Lombard League, his own son, and his bitter conflict with the papacy are the subject of countless works of fiction and non-fiction. Yolanda, on the other hand, has largely been lost in the history books because she was an unloved second wife who died less than three years after her marriage to Frederick. I wanted to give her a face and voice -- if only for a brief moment.

Cheering from the city marked the progress of the queen toward the harbor. They all turned to watch and shortly afterward, the queen’s party emerged. Yolanda was riding on a very pretty, dish-faced white palfrey decked out in a saddlecloth with the arms of Jerusalem on it. She herself wore a practical russet gown, but over this, a surcoat of white silk “dusted” with gold crosses. Her head was encased in a white, gauze wimple to mark her status as a married woman, despite the fact she was still a maiden.

The cheering of her people made the girl-queen blush with embarrassment, but it also made her smile and wave. Beirut’s heart went out to her. She was still so very young. Indeed, she was the same age as his only daughter, Bella. He couldn’t have borne the thought of sending his little girl across the water to an utter stranger, and he found his dislike of John de Brienne hardening.

Despite the death of his wife, Brienne continued to claim the crown of Jerusalem, dubiously Beirut thought, because of Yolanda. Yet he hadn’t bothered to visit her in five years. And while Beirut recognized the advantages of Yolanda’s marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, he was also a father. He loved his six children more than his own life, and sometimes more than Jerusalem. Based on what he had heard, he would not have sent his daughter Bella to marry Frederick Hohenstaufen—not for all the gold in Constantinople.

Queen Yolanda approached, flanked on one side by Eudes de Montbéliard and on the other by a young woman Beirut did not recognize. “Who is the young lady with the Queen?” Beirut asked Sidon.

“Ah, that is Eudes’ sister Eschiva. The Queen asked her to join her household,” Sidon hastened to explain, anticipating Beirut’s objections to the “parvenu” Montbéliards again successfully positioning themselves close to the crown.

To Sidon’s surprise, Beirut nodded with approval. Now that they were nearer, he recognized the girl as the most sensible of all the maidens in attendance on the Queen over the past three weeks. He had noticed and approved of the way she had kept to the background while the other girls preened and flirted—all too often with his son Balian. More important, it had been this girl who repeatedly calmed or encouraged an uncertain and nervous Yolanda. He simply had not realized that she was Montbéliard’s daughter. Now that Sidon identified her, however, he noticed that she shared a family resemblance with her brother from the bright blond hair and blue eyes to the long face and nose. Unlike her brother, however, she smiled and chattered excitedly with the Queen. Like his son Hugh, she seemed delighted to be going West, something that would surely help the Queen overcome her obvious foreboding.

As the Queen reached the gangway to the Imperial dromond, she drew up. At once, a knight from her entourage sprang down to hold her off-stirrup. As she touched the ground, a groom came forward to lead her horse away. Meanwhile, the ship’s captain descended the gangway to bend his knee, his hand on his heart, before her. Beirut was glad she was traveling on an Imperial ship commanded by a Sicilian captain because there had been some very unseemly squabbling between the Pisans, Genoese and Venetian communities of Outremer about who should have the honor of transporting the Queen and her party.

Before the captain could lead Yolanda aboard his ship, however, Beirut stepped forward. “My lady queen!” Yolanda turned, startled, in the direction of his voice. She looked at Beirut uncertainly, unsure who he was.

“John d’Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, my lady.” Beirut helped her out of her dilemma, and she broke into a wide smile.

“Of course, my lord. I should have remembered you, but I’ve met so many new people these last few weeks.”

“I understand entirely, my lady. I have come to see you off, and give you a little gift—more for your voyage than your marriage.” As he spoke he gestured to his sons, and Balian at once opened his father’s saddlebag to remove an object wrapped in painted leather. He handed this to his father, and Beirut unwrapped the leader cover to withdraw a book. This he held out to Queen Yolanda.

Eschiva de Montbéliard had come to stand behind her queen. At the sight of the book, she let out a little gasp of delight.

Beirut cast the Montbéliard girl a smile before addressing the Queen again. “This was your great-grandmother’s book. She would have wanted you to have it.”

Queen Yolanda looked up at him frowning slightly as she tried to work it out. “My great-grandmother? Queen Maria Comnena? Your mother?” Yolanda might not have recognized him, but she had learned the lessons about her dynasty well.

“Exactly.” Beirut lovingly opened the ivory cover of the book to reveal the interior, eliciting another appreciative gasp from the Montbéliard girl. “It is, I am afraid, in Greek, but I was told you were taught Greek.” It was as much a question as a statement.

The Queen nodded vigorously, going on tip-toe to see the book better. Beirut at once lowered his hands to make it easier for her to see and explained. “It is the story of a Greek sailor trying to return home after a long war in what is now the Empire of Nicaea. Along the way, he suffers many adventures and hardships that take him all across the Mediterranean. Although the journey is embellished with many fanciful beasts and mythical adventures, still I think you will find it a lively and informative companion on your journey. At least I hope you do.” Beirut bowed deeply and handed the book to his Queen.

Yolanda took it from him and held it to her still flat chest. “It is very, very kind of you, my lord! I can’t wait to read it!” For an instant, she was a little girl again rather than a queen and bride.

Beirut bowed again. “I hope it will always bring you pleasure—and remind you of your home and your heritage.”

Yolanda seemed to want to say more, but Eudes de Montbéliard was moving from foot to foot to indicate his impatience. He cleared his throat and admonished, “We do not want to miss the tide, my lady.” He always managed to sound as if he thought he knew better than everyone else, Beirut thought.

Yolanda responded as if she had been guilty of some misdeed and hastened to do as Montbéliard urged. She started for the ship, but then she stopped to say over her shoulder with heartfelt emphasis, “Thank you again, my lord! I love books!”

Montbéliard shooed his queen and his sister aboard the ship, giving her no chance to stay on deck to watch them cast off. They are prisoners already, Beirut thought—not entirely logically. Yolanda was on her way to be crowned Holy Roman Empress—arguably the most powerful woman on earth. So why did he feel so sorry for her, and so sad?

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Cheering from the city marked the progress of the queen toward the harbor. They all turned to watch and shortly afterward, the queen’s party emerged. Yolanda was riding on a very pretty, dish-faced white palfrey decked out in a saddlecloth with the arms of Jerusalem on it. She herself wore a practical russet gown, but over this, a surcoat of white silk “dusted” with gold crosses. Her head was encased in a white, gauze wimple to mark her status as a married woman, despite the fact she was still a maiden.

The cheering of her people made the girl-queen blush with embarrassment, but it also made her smile and wave. Beirut’s heart went out to her. She was still so very young. Indeed, she was the same age as his only daughter, Bella. He couldn’t have borne the thought of sending his little girl across the water to an utter stranger, and he found his dislike of John de Brienne hardening.

Despite the death of his wife, Brienne continued to claim the crown of Jerusalem, dubiously Beirut thought, because of Yolanda. Yet he hadn’t bothered to visit her in five years. And while Beirut recognized the advantages of Yolanda’s marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor, he was also a father. He loved his six children more than his own life, and sometimes more than Jerusalem. Based on what he had heard, he would not have sent his daughter Bella to marry Frederick Hohenstaufen—not for all the gold in Constantinople.

Queen Yolanda approached, flanked on one side by Eudes de Montbéliard and on the other by a young woman Beirut did not recognize. “Who is the young lady with the Queen?” Beirut asked Sidon.

“Ah, that is Eudes’ sister Eschiva. The Queen asked her to join her household,” Sidon hastened to explain, anticipating Beirut’s objections to the “parvenu” Montbéliards again successfully positioning themselves close to the crown.

To Sidon’s surprise, Beirut nodded with approval. Now that they were nearer, he recognized the girl as the most sensible of all the maidens in attendance on the Queen over the past three weeks. He had noticed and approved of the way she had kept to the background while the other girls preened and flirted—all too often with his son Balian. More important, it had been this girl who repeatedly calmed or encouraged an uncertain and nervous Yolanda. He simply had not realized that she was Montbéliard’s daughter. Now that Sidon identified her, however, he noticed that she shared a family resemblance with her brother from the bright blond hair and blue eyes to the long face and nose. Unlike her brother, however, she smiled and chattered excitedly with the Queen. Like his son Hugh, she seemed delighted to be going West, something that would surely help the Queen overcome her obvious foreboding.

As the Queen reached the gangway to the Imperial dromond, she drew up. At once, a knight from her entourage sprang down to hold her off-stirrup. As she touched the ground, a groom came forward to lead her horse away. Meanwhile, the ship’s captain descended the gangway to bend his knee, his hand on his heart, before her. Beirut was glad she was traveling on an Imperial ship commanded by a Sicilian captain because there had been some very unseemly squabbling between the Pisans, Genoese and Venetian communities of Outremer about who should have the honor of transporting the Queen and her party.

Before the captain could lead Yolanda aboard his ship, however, Beirut stepped forward. “My lady queen!” Yolanda turned, startled, in the direction of his voice. She looked at Beirut uncertainly, unsure who he was.

“John d’Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, my lady.” Beirut helped her out of her dilemma, and she broke into a wide smile.

“Of course, my lord. I should have remembered you, but I’ve met so many new people these last few weeks.”

“I understand entirely, my lady. I have come to see you off, and give you a little gift—more for your voyage than your marriage.” As he spoke he gestured to his sons, and Balian at once opened his father’s saddlebag to remove an object wrapped in painted leather. He handed this to his father, and Beirut unwrapped the leader cover to withdraw a book. This he held out to Queen Yolanda.

Eschiva de Montbéliard had come to stand behind her queen. At the sight of the book, she let out a little gasp of delight.

Beirut cast the Montbéliard girl a smile before addressing the Queen again. “This was your great-grandmother’s book. She would have wanted you to have it.”

Queen Yolanda looked up at him frowning slightly as she tried to work it out. “My great-grandmother? Queen Maria Comnena? Your mother?” Yolanda might not have recognized him, but she had learned the lessons about her dynasty well.

“Exactly.” Beirut lovingly opened the ivory cover of the book to reveal the interior, eliciting another appreciative gasp from the Montbéliard girl. “It is, I am afraid, in Greek, but I was told you were taught Greek.” It was as much a question as a statement.

The Queen nodded vigorously, going on tip-toe to see the book better. Beirut at once lowered his hands to make it easier for her to see and explained. “It is the story of a Greek sailor trying to return home after a long war in what is now the Empire of Nicaea. Along the way, he suffers many adventures and hardships that take him all across the Mediterranean. Although the journey is embellished with many fanciful beasts and mythical adventures, still I think you will find it a lively and informative companion on your journey. At least I hope you do.” Beirut bowed deeply and handed the book to his Queen.

Yolanda took it from him and held it to her still flat chest. “It is very, very kind of you, my lord! I can’t wait to read it!” For an instant, she was a little girl again rather than a queen and bride.

Beirut bowed again. “I hope it will always bring you pleasure—and remind you of your home and your heritage.”

Yolanda seemed to want to say more, but Eudes de Montbéliard was moving from foot to foot to indicate his impatience. He cleared his throat and admonished, “We do not want to miss the tide, my lady.” He always managed to sound as if he thought he knew better than everyone else, Beirut thought.

Yolanda responded as if she had been guilty of some misdeed and hastened to do as Montbéliard urged. She started for the ship, but then she stopped to say over her shoulder with heartfelt emphasis, “Thank you again, my lord! I love books!”

Montbéliard shooed his queen and his sister aboard the ship, giving her no chance to stay on deck to watch them cast off. They are prisoners already, Beirut thought—not entirely logically. Yolanda was on her way to be crowned Holy Roman Empress—arguably the most powerful woman on earth. So why did he feel so sorry for her, and so sad?

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on September 14, 2018 02:00

September 7, 2018

A Fateful Fall- Excerpt from Rebels Against Tyranny

Sometimes a seemingly minor incident can trigger a chain of events with profound consequences. According to the 13th-century historian Philip de Novare, the bitter antagonism between the Ibelins and Sir Amaury Barlais, which grew into a full-scale civil war when the Holy Roman Emperor exploited Barlais' bitterness for his own purposes, all started at a tournament...

In a series of novels, I plan to explore and describe the people and principles that tore the Holy Land apart for nearly two decades in the mid-thirteen century. The first book in this series, Rebels against Tyranny, was recently released. As is fitting, the opening scene takes the reader to that fateful tournament in 1225.

“Philip, are you all right?” a young, male voice called out anxiously.

Sir Philip of Novare couldn’t see the owner of the voice because his squire was trying to pry his misshapen great helm off his head—without taking half his face off with it. Philip had just lost a “friendly” joust. Although his opponent had used only a blunted mace, he’d still managed to bash in the side of Philip’s helm.

Philip was sweating profusely, as much from increasing panic as the heat of a Cypriot summer day. The air inside the helm seemed to grow thinner and thinner as his squire Andre twisted the metal pot to try to maneuver it past Philip’s chin. The pounding of his blood in his temples and the rasping of his breath seemed to echo inside the helmet, blotting out most other sounds. He could barely hear Andre answer the newcomer in an anxious, frightened voice. “I can’t get the helm off, sir.”

“Let me try,” the voice answered, coming nearer. “It’s me. Balian.”

“I can hardly breathe anymore, Bal,” Philip gasped.

Firm hands grasped the helmet, and a moment later the air flooded back into Philip’s lungs like a fresh breeze. Balian had twisted the helm so that both the eye slit and breathing holes were in position again. Their eyes met, and Philip could see the concern and question in Balian’s eyes. “I’m fine—if I could just get this damned thing off!” Philip assured his friend.

Balian and he had just spent the last three years earning their spurs together. Yesterday, in an extravagant ceremony, they had been knighted by Balian’s father, the powerful Lord of Beirut, along with Balian’s younger brother Baldwin and five other youths. Today’s jousting was part of the three-day celebration, which would culminate in a full-scale melee pitting the barons and knights of Syria against those of Cyprus.

Balian was already seventeen and had long felt ready for the accolade of knighthood. Philip knew that Balian was both wounded and resentful that his father had delayed his knighting so long—and then knighted his fourteen-month-younger brother at the same time. Being so close in age, the brothers had always been rivals, but the intensity of their competition was aggravated by the fact that they were very different in temperament. Baldwin was like water to Balian’s fire—and took pleasure in dousing Balian’s enthusiasm and pride. Balian’s need to prove himself better than Baldwin in front of all the peers of the realm had provoked him into taking stupid risks this morning. Fortunately, he’d gotten away with them and ridden undefeated from the lists.

Under the circumstances, Philip thought, he might have been forgiven for basking in his hard-won glory and gloating a bit instead of coming down into the dusty tent-city to find out what had happened to his friend. After all, in addition to practically every baron and knight of Outremer, there were scores of ladies and maidens in the stands. Balian had the kind of good looks that appealed to women. By the way the maidens had been biting their fingernails at Balian’s near falls and cheering his successes, Philip could imagine all too vividly the way Balian would be adulated and adored by blushing young beauties the moment he joined the spectators. Instead, Balian hadn’t even taken the time to change out of his sweat-soaked gambeson and dusty surcoat.

“I think I better fetch an armorer, Philip,” Balian told Philip after a moment of inspection.

“He’ll want to cut it open!” Philip protested with a new kind of panic. Unlike Balian who was heir to the lordship of Beirut, son of one of the richest men in both Syria and Cyprus, Philip was an orphan. His father, a knight from Lombardy, had died during the first siege of Damietta when he was only twelve. A Cypriot, Sir Peter Chappe, had taken Philip under his wing, letting him serve as his page until Philip’s skill at reading earned him the patronage of a more powerful lord, Sir Ralph of Tiberias. The latter had been nearing death, however, and Philip had soon found himself without a lord, let alone a fief. Balian’s father had rescued him by bestowing a small Cypriot fief upon him and sending him to serve as a squire in his brother’s household, where he had met and befriended Balian. Philip had spent all the cash he could raise from his one fief just to outfit himself—and now his expensive helm was in risk of being ruined beyond repair.

“Very probably,” Balian agreed calmly, and Philip knew his friend just couldn’t understand. Balian’s armor had cost twice as much in the first place, and he wouldn’t have given a thought to replacing it on a whim. Balian didn’t hesitate to wear silk surcoats on the tiltyard either or buy a sword with an enameled pommel or a saddle with ivory inlays.

“Balian! I can’t afford a new helmet!” Philip protested in exasperation.

“You can’t exactly spend the rest of your life wearing that one either,” Balian retorted practically. “You can’t drink or eat in it for a start. I’m going to fetch the armorer. Andre?” He turned to his friend’s young, inexperienced and frightened squire.

“Yes, my lord?”

“Draw a cold bath for Sir Philip. When we get him out of that thing, he’s going to need to cool off. He very likely got a concussion and doesn’t even know it yet.”

“Yes, my lord.”

“I’ll be right back, Philip,” Balian assured his friend, and ducked under the partially opened tent flap.

Outside Philip’s tent, Balian was in a city of canvas. Literally, hundreds of lords and knights had pitched their tents on the plain west of Limassol to take part in this sporting event. Tournaments had been popular in France and Flanders for nearly a century, but for most of that time, the knights and lords of Outremer had been engaged in too much real warfare against the Saracens to seek mock combat. The last decades, however, had been comparatively settled due to squabbling between the heirs of al-Adil. With the Ayyubids fighting among themselves, the Franks had been given a respite from war, and their appetite for sport had grown commensurately.

Although the actual lists were a couple hundred yards away, the dust churned up by the jousting wafted on the wind across the tent city, turning the air a murky beige and the sound of cheering and shouting was only slightly dampened. Clearly, the current joust was exciting the crowd because the shouts and collective groans seemed particularly intense. Balian, however, only glanced in the direction of the lists, knowing that the matches scheduled for this afternoon did not include any of his friends or family. Instead, he tried to decide the best way through the rows of tents to the armorers who had set up shops along the far periphery.

He had only gone a few steps when a new roar of agitation rose from the bleachers. People seemed to be shouting, “Stop! Stop!”

Balian paused to look in the direction of the lists and saw a little man come storming out on foot. It was Sir Amaury Barlais. He was covered with sand, evidently from a tumble, but that was hardly unusual. What was striking was that he was beet red with fury as he cursed and gestured. “I’ll kill him! I swear! I’ll kill him! He was cheating! It was obvious! If they refuse to see that, they’re all cheats and liars!”

Two other knights were running after him, his cousin Sir Grimbert de Bethsan and Sir Gauvain de Cheveché. “Amaury, you might be right that Sir Toringuel was cheating, but it does you no good to accuse the baillie of being in cahoots with him—”

“Why shouldn’t I? Damn it! Toringuel is Ibelin’s knight. If he was cheating, it was with his knowledge and consent!”

Balian flinched at such an accusation. Aside from being baillie, his uncle was an Ibelin, and he had been raised to believe that all Ibelins had an obligation to live by the very highest standards of chivalry. From the time he was a little boy, it had been beaten into him that as an Ibelin he had to be more honest, more charitable, more loyal, more diligent, more persistent, more courageous, more compassionate—in short more noble than other men. That he didn’t always live up to that ideal was obvious, but he had never expected to hear anyone impute that his uncle fell short of the highest standards. People might not like all of his policies, but Balian had never before heard anyone accuse his uncle of anything dishonorable.

Sir Grimbert made a second attempt to calm Barlais. “You don’t know that, Amaury. If you’re so sure Sir Toringuel was cheating, then demand an inspection of his weapons, but don’t lash out at the judges! That only makes them disinclined to support you!”

“They’re all a bunch of bastards!” Barlais insisted, his rage so intense that his veins were pulsing in his temples as he tore off his coif and arming cap. He was in his mid-thirties and his hair was thinning over angular features that made Balian’s friend Philip de Novare compare him to a weasel. The latter image was reinforced because he wore his short, brown hair slicked back away from his sharp face. He ducked into a tent like a rodent going to earth, but as Balian passed by he was still raging, “I’ll kill him! I swear, I’ll kill him!”

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

In a series of novels, I plan to explore and describe the people and principles that tore the Holy Land apart for nearly two decades in the mid-thirteen century. The first book in this series, Rebels against Tyranny, was recently released. As is fitting, the opening scene takes the reader to that fateful tournament in 1225.

“Philip, are you all right?” a young, male voice called out anxiously.

Sir Philip of Novare couldn’t see the owner of the voice because his squire was trying to pry his misshapen great helm off his head—without taking half his face off with it. Philip had just lost a “friendly” joust. Although his opponent had used only a blunted mace, he’d still managed to bash in the side of Philip’s helm.

Philip was sweating profusely, as much from increasing panic as the heat of a Cypriot summer day. The air inside the helm seemed to grow thinner and thinner as his squire Andre twisted the metal pot to try to maneuver it past Philip’s chin. The pounding of his blood in his temples and the rasping of his breath seemed to echo inside the helmet, blotting out most other sounds. He could barely hear Andre answer the newcomer in an anxious, frightened voice. “I can’t get the helm off, sir.”

“Let me try,” the voice answered, coming nearer. “It’s me. Balian.”

“I can hardly breathe anymore, Bal,” Philip gasped.

Firm hands grasped the helmet, and a moment later the air flooded back into Philip’s lungs like a fresh breeze. Balian had twisted the helm so that both the eye slit and breathing holes were in position again. Their eyes met, and Philip could see the concern and question in Balian’s eyes. “I’m fine—if I could just get this damned thing off!” Philip assured his friend.

Balian and he had just spent the last three years earning their spurs together. Yesterday, in an extravagant ceremony, they had been knighted by Balian’s father, the powerful Lord of Beirut, along with Balian’s younger brother Baldwin and five other youths. Today’s jousting was part of the three-day celebration, which would culminate in a full-scale melee pitting the barons and knights of Syria against those of Cyprus.

Balian was already seventeen and had long felt ready for the accolade of knighthood. Philip knew that Balian was both wounded and resentful that his father had delayed his knighting so long—and then knighted his fourteen-month-younger brother at the same time. Being so close in age, the brothers had always been rivals, but the intensity of their competition was aggravated by the fact that they were very different in temperament. Baldwin was like water to Balian’s fire—and took pleasure in dousing Balian’s enthusiasm and pride. Balian’s need to prove himself better than Baldwin in front of all the peers of the realm had provoked him into taking stupid risks this morning. Fortunately, he’d gotten away with them and ridden undefeated from the lists.

Under the circumstances, Philip thought, he might have been forgiven for basking in his hard-won glory and gloating a bit instead of coming down into the dusty tent-city to find out what had happened to his friend. After all, in addition to practically every baron and knight of Outremer, there were scores of ladies and maidens in the stands. Balian had the kind of good looks that appealed to women. By the way the maidens had been biting their fingernails at Balian’s near falls and cheering his successes, Philip could imagine all too vividly the way Balian would be adulated and adored by blushing young beauties the moment he joined the spectators. Instead, Balian hadn’t even taken the time to change out of his sweat-soaked gambeson and dusty surcoat.

“I think I better fetch an armorer, Philip,” Balian told Philip after a moment of inspection.