Helena P. Schrader's Blog, page 32

November 9, 2018

Why I Write Part I - To Learn

By the end of this year I will have retired from the U.S. Department of State and will be able to devote myself full-time to the business of writing. I thought that was a good moment to reflect on why I write -- and to share those thoughts with my loyal fans and followers. In this seven part series, I will explore the seven most important motivations that I feel: 1) to learn, 2) to explore, 3) to question, 4) to educate, 5) to share, 6) to critique, and 7) to reach a larger audience.

It would probably surprise no one if I said that I read in order to learn, but writing to learn likely strikes many as putting the cart before the horse. Surely one doesn't write about something unless they already know about it?

It would probably surprise no one if I said that I read in order to learn, but writing to learn likely strikes many as putting the cart before the horse. Surely one doesn't write about something unless they already know about it?

True. But that is precisely the point.

If I am intrigued by a topic (period, culture, event etc.) enough to want to write about it, then I am setting myself on a course of study. In order to be able to write about this topic, I will have to do my research.

I'm not someone who can just dash off a short-story based on a casual thought or a snippet of information I've stumbled across. I envy those who can write like that! But I'm at heart a historian and I can't write even a short story without knowing about things like how people dressed, kept warm, what they ate, how they traveled, what their religious beliefs were likely to be etc. etc.

If I'm going to write, I'm going to have to research all those things, so there's no point getting started unless I'm 1) willing to invest that effort and 2) going to use what I learn for more than one project. In other words, I may read a book simply because someone recommends it to me and I will be the richer for reading, but if I want to write about something I need to learn more. It is not enough to know about the events or even the people described, I must also understand the environment in which the events unfold. That requires learning about, for example, climate, geography, and contemporary architecture. I also need to describe, as I noted earlier, what people were likely to have eaten, how they dressed, the kind of entertainment they would have been able to enjoy, and the means of transport at their disposal. I need to understand social structures, legal norms, religious beliefs and the economics of the time.

In other words, by choosing to write about a topic, I ensure that I thoroughly learn about it in much greater detail than would be the case if I simply read about it.

You may also remember your parents or teachers saying that "to teach once is to learn twice." Writing is much the same. What I have read but not written about, I am far more likely to forget. What I have written about I learn with an intensity that stays with me for many years.

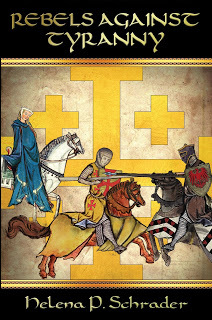

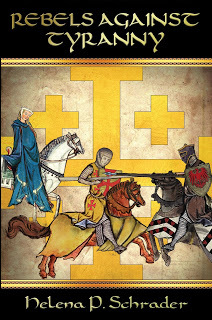

My current learning adventure is a deep-dive into the colorful and exiting world of 13th century Outremer. You can discover it with and through me in the first of my latest series:

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

It would probably surprise no one if I said that I read in order to learn, but writing to learn likely strikes many as putting the cart before the horse. Surely one doesn't write about something unless they already know about it?

It would probably surprise no one if I said that I read in order to learn, but writing to learn likely strikes many as putting the cart before the horse. Surely one doesn't write about something unless they already know about it?True. But that is precisely the point.

If I am intrigued by a topic (period, culture, event etc.) enough to want to write about it, then I am setting myself on a course of study. In order to be able to write about this topic, I will have to do my research.

I'm not someone who can just dash off a short-story based on a casual thought or a snippet of information I've stumbled across. I envy those who can write like that! But I'm at heart a historian and I can't write even a short story without knowing about things like how people dressed, kept warm, what they ate, how they traveled, what their religious beliefs were likely to be etc. etc.

If I'm going to write, I'm going to have to research all those things, so there's no point getting started unless I'm 1) willing to invest that effort and 2) going to use what I learn for more than one project. In other words, I may read a book simply because someone recommends it to me and I will be the richer for reading, but if I want to write about something I need to learn more. It is not enough to know about the events or even the people described, I must also understand the environment in which the events unfold. That requires learning about, for example, climate, geography, and contemporary architecture. I also need to describe, as I noted earlier, what people were likely to have eaten, how they dressed, the kind of entertainment they would have been able to enjoy, and the means of transport at their disposal. I need to understand social structures, legal norms, religious beliefs and the economics of the time.

In other words, by choosing to write about a topic, I ensure that I thoroughly learn about it in much greater detail than would be the case if I simply read about it.

You may also remember your parents or teachers saying that "to teach once is to learn twice." Writing is much the same. What I have read but not written about, I am far more likely to forget. What I have written about I learn with an intensity that stays with me for many years.

My current learning adventure is a deep-dive into the colorful and exiting world of 13th century Outremer. You can discover it with and through me in the first of my latest series:

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Published on November 09, 2018 04:00

November 2, 2018

Difficult Choices - An Excerpt from Rebels against Tyranny -

One of the apparent paradoxes in Novare's account of events in 1229 is that although he claims Beirut's sons were abused while held as hostages, he also claims that Balian "willingly" and "gladly" agreed to serve in the Emperor's household. Historian Peter Edbury suggests that there was nothing "voluntary" about Balian's service to the Emperor and that both he and his younger brother John were being kept "under surveillance" to ensure their father's good behavior. In this scene, I suggest a possible alternative explanation of what happened. It is true that Frederick took Henry of Cyprus with him on "crusade" -- although Henry was just eleven years old -- and I think that Henry was the real hostage.

Beirut rode back to his camp with his freed sons beside him, but they did not speak. Nor was the mood one of rejoicing, as he had expected. Although Baldwin smiled at him more than once, Balian had withdrawn within himself. He appeared to be brooding.

At last, they reached the camp. At the sight of Beirut flanked by his sons, the knights, soldiers, and archers began to cheer—until they got a better look at the two hostages. Then the cheers died on their lips and they looked at one another and started shaking their heads and muttering.

Hugh and Johnny came spurring forward to greet their brothers, but their welcomes turned into exclamations of “Oh, my God!” and “Jesus! What did he do to you?”

“Later!” Their father told them, and they dutifully fell silent as they turned their horses to fall in beside their brothers, sobered.

At Beirut’s large tent, they drew up and started to dismount. Balian hesitated, staring at the ground for a long time while Rob, his father, brothers, and Novare waited. Finally, he took a deep breath and swung his right leg forward over the pommel to drop down on the ground. As he landed, he gasped in pain and his legs gave way under him. He went down on his knees, and at once a dozen hands reached out to help. He took one without looking at who it was and grasped it so hard to pull himself upright that Johnny whelped in pain before turning to stare at his father in horror.

Beirut bade Novare bring the physician to his tent at once.

Novare agreed readily, turning his horse over to his squire as he hastened to find the Ibelin’s physician Joscelyn d’Auber.

Meanwhile, Beirut gently pushed his younger sons aside and put his arm around Balian and guided him to the tent. Balian paused to find Karpas in the crowd behind his father. “Thank you, Sir Anseau. I don’t know what I would have done without your horse.”

“Your horse now, Balian,” Karpas told him without a moment’s hesitation. “He’s called Damon, and he doesn’t like me much. He remembers me trying to kill his rider in the judicial combat and holds it against me, but I’m sure you’ll be able to win him over.”

“But—thank you!” Balian appeared almost overwhelmed. “I owe you a great deal, my lord,” he continued, and his father had the impression he was about to break down as he stammered. “I—”

“Don’t worry!” Karpas cut him off with a grin. “I’ll keep track and charge interest!” His quip and laugh dissipated the awkwardness and drew a weak but grateful smile from Balian.

Beirut gave Karpas a nod of thanks too, then asked the others of his party, all of whom were still staring in shock, to give him time alone with his sons. They withdrew with a murmur of well-wishes, while Beirut guided his eldest son into his tent, and Baldwin held open the flap for both of them.

Beirut led Balian to his own cushioned chair and had him sit down.

“I’m sorry, Father,” Balian whispered.

Beirut just put a hand on his shoulder, then looked over his own. “Hugh, Johnny, bring us all wine.”

The younger youths sprang to obey as Beirut directed his attention to Baldwin next. “Are you alright? Come. Sit down.” He gestured to the only other chair in the room.

Baldwin accepted the invitation to sit, but insisted, “I’m fine, Father. They treated me better than Balian from the start.” He cast a glance at his older brother, and Balian answered with a look that Beirut intercepted. He had the strong feeling Balian had just wordlessly asked Baldwin not to tell something.

Beirut immediately announced, “I want to know everything — everything — they did to you from the moment I abandoned you in the great hall. And then I want to know why you just volunteered not only yourself but Johnny to serve in that—” Beirut bit his tongue but then said it anyway “— that monster’s household.”

Balian took a deep breath and put his hand on his father’s arm. When Beirut looked at him, he said slowly and deliberately, “Because, Father, he has the King.”

“What do you mean?” Beirut asked irritated.

“I mean he has taken King Henry with him on this expedition, in his own ship, watched day and night by his minions.”

Beirut stared at his son in disbelief. “That can’t be! King Henry’s only eleven years old!”

“I know. And the only way we can try to help him—and possibly remind him that we are not his enemies—is if one or the other of us are in the imperial household. Johnny is closest in age to Henry, and as a squire of the body might even be able to worm his way into a position where he can share Henry’s chamber and meals. As for me, if I’m in the household, I’ll at least have some idea of what is happening. I can try to protect them both—assuming I can regain enough strength to wield a sword ever again,” he added with a surge of bitterness.

Beirut spun about to look at Johnny, who was bringing four brass goblets from one of the carved chests.

“What is it?” Johnny asked.

“The Emperor offered you a place in his household, as his squire, and your brother accepted for you—without my consent, so it is not yet decided. I will make my excuses to the Emperor and bear the consequences. I am not inclined to put any son of mine at his non-existent mercy ever again.”

“Father, listen to me,” Balian interceded. Beirut had sworn on the night of the infamous banquet that he would never again disregard anything Balian told him. Against his instincts, he bit his tongue and waited for his son to continue. “If not for King Henry, I am not sure I would be alive today.” Balian paused to let the words sink in before explaining, “The Emperor threatened to throw us, bound hand and foot, to the sharks—after watching you hang.”

“He’s not exaggerating, Father,” Baldwin hastened to support his brother. “The Emperor argued that your rebellion gave him the right to execute us. Although he promised to keep us alive long enough to watch you hang, I’m not sure Balian would have lasted. He was without water for almost two days. If King Henry hadn’t gone to the Hospitaller Master and insisted on visiting us, it might have been longer. Master de Montaigu was appalled to discover the condition we were in and personally took us under the protection of the Hospital. He ensured that Balian was taken to the Hospital infirmary and received treatment there.”

Beirut absorbed this with no visible display of emotion on his face—only fingers that could not stay still. First, they went to cover his mouth and chin, then fell to his chest and clasped his cross. He looked from his eldest to his second son uneasily.

Behind him, Hugh spoke up for the first time. “It was Rob who went to the Hospital and found out from the lay-brothers that you were being kept apart from the other hostages. He was the one who guessed you were being mistreated.”

Beirut at once smiled over his shoulder at his third son and agreed. “Yes, that’s true. While the rest of us withdrew immediately to Nicosia, Rob stayed behind to find out what had happened to you. I don’t know how he got an audience with the King, but he must have gotten a message to him somehow.” Beirut paused and added, “I never, never thought a Christian monarch could treat innocent hostages like criminals. Please forgive me for being so... naïve.”

Balian almost laughed at that, and he reached out to his father. “I was never prouder of you than when you stood up to him and walked out, taking most of the Cypriot barons and knights with you.” Then he added in a voice smoldering with hatred, “I would rather die, than watch you grovel at his feet.”

“Balian speaks for me as well, Father,” Baldwin joined in earnestly. Beirut looked from one to the other, noting that the Lord had brought good even out of this terrible situation because the brothers had clearly buried their differences and found the love and respect for one another they should have as brothers. Still, he shook his head and asked, “How did it come to this? That we are subjects of a man without honor or Christian charity?”

“That fool Brienne was too damn eager for his daughter to wear an imperial crown, that’s how! He’s certainly lived to regret it,” Baldwin retorted. Balian nodded agreement, adding, “But the way I see it, our real king is Henry, and he is now in acute danger. Not that the Emperor wants to humiliate him as he did us, but he does want to rob him of his inheritance by turning him into a puppet. He will certainly try to turn him against us. The fact that King Henry interceded on our behalf proves that the Emperor has not yet succeeded, but how much longer can we expect an eleven-year-old to hold out? Especially now that he is cut off from his own household?”

Beirut shook his head to indicate he did not know what to think, then turned to look at his son Johnny. “What do you think? Would you be willing to serve as a squire to the Holy Roman Emperor after what he did to your brothers?”

Johnny looked from Balian to Baldwin and then faced his father with his chin at an impudent angle as he declared, “I’m an Ibelin too, you know? If Balian and Baldwin can survive as the Emperor’s prisoners, I’m sure I can survive as his squire.”

Baldwin grinned at him and declared, “Well said, Johnny!”

“I will protect him with my life, Father,” Balian swore, but the very solemnity with which he said it and the dark circles around his eyes made his father shudder.

“I don’t doubt that you would try, Balian, but the sight of you does not inspire me with confidence! Rather, the Emperor might manage to kill you both!”

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Beirut rode back to his camp with his freed sons beside him, but they did not speak. Nor was the mood one of rejoicing, as he had expected. Although Baldwin smiled at him more than once, Balian had withdrawn within himself. He appeared to be brooding.

At last, they reached the camp. At the sight of Beirut flanked by his sons, the knights, soldiers, and archers began to cheer—until they got a better look at the two hostages. Then the cheers died on their lips and they looked at one another and started shaking their heads and muttering.

Hugh and Johnny came spurring forward to greet their brothers, but their welcomes turned into exclamations of “Oh, my God!” and “Jesus! What did he do to you?”

“Later!” Their father told them, and they dutifully fell silent as they turned their horses to fall in beside their brothers, sobered.

At Beirut’s large tent, they drew up and started to dismount. Balian hesitated, staring at the ground for a long time while Rob, his father, brothers, and Novare waited. Finally, he took a deep breath and swung his right leg forward over the pommel to drop down on the ground. As he landed, he gasped in pain and his legs gave way under him. He went down on his knees, and at once a dozen hands reached out to help. He took one without looking at who it was and grasped it so hard to pull himself upright that Johnny whelped in pain before turning to stare at his father in horror.

Beirut bade Novare bring the physician to his tent at once.

Novare agreed readily, turning his horse over to his squire as he hastened to find the Ibelin’s physician Joscelyn d’Auber.

Meanwhile, Beirut gently pushed his younger sons aside and put his arm around Balian and guided him to the tent. Balian paused to find Karpas in the crowd behind his father. “Thank you, Sir Anseau. I don’t know what I would have done without your horse.”

“Your horse now, Balian,” Karpas told him without a moment’s hesitation. “He’s called Damon, and he doesn’t like me much. He remembers me trying to kill his rider in the judicial combat and holds it against me, but I’m sure you’ll be able to win him over.”

“But—thank you!” Balian appeared almost overwhelmed. “I owe you a great deal, my lord,” he continued, and his father had the impression he was about to break down as he stammered. “I—”

“Don’t worry!” Karpas cut him off with a grin. “I’ll keep track and charge interest!” His quip and laugh dissipated the awkwardness and drew a weak but grateful smile from Balian.

Beirut gave Karpas a nod of thanks too, then asked the others of his party, all of whom were still staring in shock, to give him time alone with his sons. They withdrew with a murmur of well-wishes, while Beirut guided his eldest son into his tent, and Baldwin held open the flap for both of them.

Beirut led Balian to his own cushioned chair and had him sit down.

“I’m sorry, Father,” Balian whispered.

Beirut just put a hand on his shoulder, then looked over his own. “Hugh, Johnny, bring us all wine.”

The younger youths sprang to obey as Beirut directed his attention to Baldwin next. “Are you alright? Come. Sit down.” He gestured to the only other chair in the room.

Baldwin accepted the invitation to sit, but insisted, “I’m fine, Father. They treated me better than Balian from the start.” He cast a glance at his older brother, and Balian answered with a look that Beirut intercepted. He had the strong feeling Balian had just wordlessly asked Baldwin not to tell something.

Beirut immediately announced, “I want to know everything — everything — they did to you from the moment I abandoned you in the great hall. And then I want to know why you just volunteered not only yourself but Johnny to serve in that—” Beirut bit his tongue but then said it anyway “— that monster’s household.”

Balian took a deep breath and put his hand on his father’s arm. When Beirut looked at him, he said slowly and deliberately, “Because, Father, he has the King.”

“What do you mean?” Beirut asked irritated.

“I mean he has taken King Henry with him on this expedition, in his own ship, watched day and night by his minions.”

Beirut stared at his son in disbelief. “That can’t be! King Henry’s only eleven years old!”

“I know. And the only way we can try to help him—and possibly remind him that we are not his enemies—is if one or the other of us are in the imperial household. Johnny is closest in age to Henry, and as a squire of the body might even be able to worm his way into a position where he can share Henry’s chamber and meals. As for me, if I’m in the household, I’ll at least have some idea of what is happening. I can try to protect them both—assuming I can regain enough strength to wield a sword ever again,” he added with a surge of bitterness.

Beirut spun about to look at Johnny, who was bringing four brass goblets from one of the carved chests.

“What is it?” Johnny asked.

“The Emperor offered you a place in his household, as his squire, and your brother accepted for you—without my consent, so it is not yet decided. I will make my excuses to the Emperor and bear the consequences. I am not inclined to put any son of mine at his non-existent mercy ever again.”

“Father, listen to me,” Balian interceded. Beirut had sworn on the night of the infamous banquet that he would never again disregard anything Balian told him. Against his instincts, he bit his tongue and waited for his son to continue. “If not for King Henry, I am not sure I would be alive today.” Balian paused to let the words sink in before explaining, “The Emperor threatened to throw us, bound hand and foot, to the sharks—after watching you hang.”

“He’s not exaggerating, Father,” Baldwin hastened to support his brother. “The Emperor argued that your rebellion gave him the right to execute us. Although he promised to keep us alive long enough to watch you hang, I’m not sure Balian would have lasted. He was without water for almost two days. If King Henry hadn’t gone to the Hospitaller Master and insisted on visiting us, it might have been longer. Master de Montaigu was appalled to discover the condition we were in and personally took us under the protection of the Hospital. He ensured that Balian was taken to the Hospital infirmary and received treatment there.”

Beirut absorbed this with no visible display of emotion on his face—only fingers that could not stay still. First, they went to cover his mouth and chin, then fell to his chest and clasped his cross. He looked from his eldest to his second son uneasily.

Behind him, Hugh spoke up for the first time. “It was Rob who went to the Hospital and found out from the lay-brothers that you were being kept apart from the other hostages. He was the one who guessed you were being mistreated.”

Beirut at once smiled over his shoulder at his third son and agreed. “Yes, that’s true. While the rest of us withdrew immediately to Nicosia, Rob stayed behind to find out what had happened to you. I don’t know how he got an audience with the King, but he must have gotten a message to him somehow.” Beirut paused and added, “I never, never thought a Christian monarch could treat innocent hostages like criminals. Please forgive me for being so... naïve.”

Balian almost laughed at that, and he reached out to his father. “I was never prouder of you than when you stood up to him and walked out, taking most of the Cypriot barons and knights with you.” Then he added in a voice smoldering with hatred, “I would rather die, than watch you grovel at his feet.”

“Balian speaks for me as well, Father,” Baldwin joined in earnestly. Beirut looked from one to the other, noting that the Lord had brought good even out of this terrible situation because the brothers had clearly buried their differences and found the love and respect for one another they should have as brothers. Still, he shook his head and asked, “How did it come to this? That we are subjects of a man without honor or Christian charity?”

“That fool Brienne was too damn eager for his daughter to wear an imperial crown, that’s how! He’s certainly lived to regret it,” Baldwin retorted. Balian nodded agreement, adding, “But the way I see it, our real king is Henry, and he is now in acute danger. Not that the Emperor wants to humiliate him as he did us, but he does want to rob him of his inheritance by turning him into a puppet. He will certainly try to turn him against us. The fact that King Henry interceded on our behalf proves that the Emperor has not yet succeeded, but how much longer can we expect an eleven-year-old to hold out? Especially now that he is cut off from his own household?”

Beirut shook his head to indicate he did not know what to think, then turned to look at his son Johnny. “What do you think? Would you be willing to serve as a squire to the Holy Roman Emperor after what he did to your brothers?”

Johnny looked from Balian to Baldwin and then faced his father with his chin at an impudent angle as he declared, “I’m an Ibelin too, you know? If Balian and Baldwin can survive as the Emperor’s prisoners, I’m sure I can survive as his squire.”

Baldwin grinned at him and declared, “Well said, Johnny!”

“I will protect him with my life, Father,” Balian swore, but the very solemnity with which he said it and the dark circles around his eyes made his father shudder.

“I don’t doubt that you would try, Balian, but the sight of you does not inspire me with confidence! Rather, the Emperor might manage to kill you both!”

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on November 02, 2018 03:00

October 26, 2018

The Holy Roman Emperor in the Holy City - An Excerpt from Rebels against Tyranny

This excerpt is based on first hand accounts of Frederick II's visit to the Holy City, including the Arab sources that tell us about the Qadi and his reaction to Frederick's actions.

At the entrance to the Temple Mount, Frederick and his escort of Teutonic and Imperial knights dismounted again and passed through the gate. Here Frederick waited for the qadi of Nablus to catch up with him while gazing up at the great, golden dome. When the Muslim cleric rejoined him, Frederick noted, “It is a beautiful structure—far more magnificent than the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Is it true that that madman Balian d’Ibelin stripped the gold from it during the last siege?”

The qadi bowed deeply. “It is true, your majesty. He is said to have used the gold to pay the mercenaries that defended the city against the forces of Salah ad-Din.”

“Barbarian!” Frederick dismissed Beirut’s father with contempt. The qadi gestured for Frederick to proceed, and they mounted the steps and crossed the wide paved platform in the direction of the great mosque. Frederick kept nodding in approval as his eyes swept over the mosaics of the exterior. Then his eyes fell on a marble plaque. He paused to read it, deciphering the Arabic out loud. “The Great Sultan Salah ad-Din, may Allah’s blessing be upon him, purified this city of the polytheists. Ah ha!” Frederick turned to grin at the embarrassed qadi. “So who were the polytheists?”

The Muslim scholar opened his mouth and closed it again, bowing deeply in embarrassment as Frederick burst out laughing. He passed into the interior of the mosque with the qadi trailing unhappily in his wake. Fredrick looked about as any tourist would, noting the interior decorations with approval before wandering over to the “rock” itself. This was protected by an iron fence and screen. “What’s this for?” he asked over his shoulder to the qadi. “Something to keep out the pigs?” He jovially referred to the Christians by another name popular among Muslims.

The qadi looked as if he wanted to sink into the foundations, while Frederick again laughed heartily at his own joke.

His tour of the Dome of the Rock complete, Frederick proceeded toward the al-Aqsa mosque—that large complex that had served as Templar headquarters and which the greedy bastards valued more than the rest of Jerusalem put together. Ahead of him a throng of pilgrims of the poorer sort were already gathered, oblivious to the fact that the Holy Roman Emperor had arrived by the other gate to the Temple Mount. They were shuffling forward to pass through the narrow entrance guarded by some Mamlukes.

The Mamlukes looked angry and disgusted, Frederick noted, and he imagined they thoroughly disapproved of the terms of the Treaty that gave Christian pilgrims the right to set foot on the Temple Mount at all. The terms were restrictive, but they did grant those in Frederick’s army the right to visit all the “holy” sites—even if Fredrick couldn’t see what was “holy” about the Knights Templar’s former headquarters.

Shaking his head in disgust, his eyes fell on a priest clutching a copy of the Bible in his hand. Frederick instantly lost his temper. “You tactless idiot!” he called out.

At once all the pilgrims turned to stare in astonishment. At the sight of the Holy Roman Emperor still wearing the Imperial crown and robes, they fell to their knees in awe.

Fredrick waded into the crowd, grabbed the stupid priest by his arm and yanked him to his feet. “How dare you come in here with a Bible? Don’t you realize this is a sacred Muslim site! You are here as a guest only! You have no business carrying a Bible with you! Get out! Out!” The Emperor shoved his knee into the priest’s backside to lend his words greater force, and the man stumbled over his own robes as he staggered forward. “Go!” Frederick shouted after him, and the man started running, with a backward look at Frederick as if the Emperor was mad.

Turning to his host, Frederick intoned, “We apologize for the tactless stupidity of our subjects, o qadi.”

The qadi of Nablus bowed deeply in reply, but he failed to disguise his intense disapproval.

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

At the entrance to the Temple Mount, Frederick and his escort of Teutonic and Imperial knights dismounted again and passed through the gate. Here Frederick waited for the qadi of Nablus to catch up with him while gazing up at the great, golden dome. When the Muslim cleric rejoined him, Frederick noted, “It is a beautiful structure—far more magnificent than the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Is it true that that madman Balian d’Ibelin stripped the gold from it during the last siege?”

The qadi bowed deeply. “It is true, your majesty. He is said to have used the gold to pay the mercenaries that defended the city against the forces of Salah ad-Din.”

“Barbarian!” Frederick dismissed Beirut’s father with contempt. The qadi gestured for Frederick to proceed, and they mounted the steps and crossed the wide paved platform in the direction of the great mosque. Frederick kept nodding in approval as his eyes swept over the mosaics of the exterior. Then his eyes fell on a marble plaque. He paused to read it, deciphering the Arabic out loud. “The Great Sultan Salah ad-Din, may Allah’s blessing be upon him, purified this city of the polytheists. Ah ha!” Frederick turned to grin at the embarrassed qadi. “So who were the polytheists?”

The Muslim scholar opened his mouth and closed it again, bowing deeply in embarrassment as Frederick burst out laughing. He passed into the interior of the mosque with the qadi trailing unhappily in his wake. Fredrick looked about as any tourist would, noting the interior decorations with approval before wandering over to the “rock” itself. This was protected by an iron fence and screen. “What’s this for?” he asked over his shoulder to the qadi. “Something to keep out the pigs?” He jovially referred to the Christians by another name popular among Muslims.

The qadi looked as if he wanted to sink into the foundations, while Frederick again laughed heartily at his own joke.

His tour of the Dome of the Rock complete, Frederick proceeded toward the al-Aqsa mosque—that large complex that had served as Templar headquarters and which the greedy bastards valued more than the rest of Jerusalem put together. Ahead of him a throng of pilgrims of the poorer sort were already gathered, oblivious to the fact that the Holy Roman Emperor had arrived by the other gate to the Temple Mount. They were shuffling forward to pass through the narrow entrance guarded by some Mamlukes.

The Mamlukes looked angry and disgusted, Frederick noted, and he imagined they thoroughly disapproved of the terms of the Treaty that gave Christian pilgrims the right to set foot on the Temple Mount at all. The terms were restrictive, but they did grant those in Frederick’s army the right to visit all the “holy” sites—even if Fredrick couldn’t see what was “holy” about the Knights Templar’s former headquarters.

Shaking his head in disgust, his eyes fell on a priest clutching a copy of the Bible in his hand. Frederick instantly lost his temper. “You tactless idiot!” he called out.

At once all the pilgrims turned to stare in astonishment. At the sight of the Holy Roman Emperor still wearing the Imperial crown and robes, they fell to their knees in awe.

Fredrick waded into the crowd, grabbed the stupid priest by his arm and yanked him to his feet. “How dare you come in here with a Bible? Don’t you realize this is a sacred Muslim site! You are here as a guest only! You have no business carrying a Bible with you! Get out! Out!” The Emperor shoved his knee into the priest’s backside to lend his words greater force, and the man stumbled over his own robes as he staggered forward. “Go!” Frederick shouted after him, and the man started running, with a backward look at Frederick as if the Emperor was mad.

Turning to his host, Frederick intoned, “We apologize for the tactless stupidity of our subjects, o qadi.”

The qadi of Nablus bowed deeply in reply, but he failed to disguise his intense disapproval.

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on October 26, 2018 11:00

October 19, 2018

The Loneliness of Kings - An Excerpt from Rebels against Tyranny

With the arrival of Emperor Frederick in Cyprus, King Henry was isolated from his previous advisors and became a virtual prisoner of the Hohenstaufen's men. He was treated courteously -- but like a puppet. His later behavior suggests just how much he came to hate both Frederick and his local supporters. In this scene the nine-year-old monarch reflects on his position with his only sympathetic companion: the lion in his menagerie.

King Henry was in his menagerie. It had always been one of his favorite places, but since the arrival of the Holy Roman Emperor, he spent more time here than usual. His Sicilian watchdogs didn’t like the stink of the big cats and made disgusted faces, preferring to stay outside in the garden when Henry visited the cats. Henry didn’t like the smell either, but he found that the longer he stayed the less he noticed it, and so, whenever he wanted to escape the company of the various imperial officials the Emperor imposed on him, he came and conversed with the lion.

“We’re in the same situation,” Henry explained, looking into the unblinking, golden eyes of the lion. “You can’t run free and be with your friends, and neither can I. But at least you don’t have to listen to lectures all day long,” Henry added. The Emperor insisted that King Henry needed more “education” and had assigned him instructors, particularly for the natural sciences and mathematics. That was bad enough, Henry felt, but what he really resented was that whenever the “the wonder of the world,” Frederick Hohenstaufen, spoke with him, the latter spent most of the time telling Henry how evil and insidious his former friends were.

“Maybe Lord Philip did keep some of my revenues for himself,” Henry told the lion, who yawned at him, letting out a puff of bad-smelling breath. “But it isn’t as if I went without anything I needed or wanted,” Henry pointed out.

The lion slowly pulled his hind feet under him and pushed himself upright. He sauntered over to the bars of his cage and looked more intently at Henry, who was sitting on the floor outside the cage with his back against the wall.

“Nor is the Emperor a particularly good king,” Henry informed the attentive lion. “If he was, then people wouldn’t keep rebelling against him. First, he drove the Lord of Beirut into rebellion by threatening to take away Beirut, and now all of Apulia is in revolt. Apulia,” Henry explained to the lion, “are the lands in Southern Italy that belong to the Kingdom of Sicily. For weeks now, messengers arrive practically every day reporting on yet another city that has either fallen or just gone over to the Pope without a fight. And you know the best of it?” Henry asked the lion, who decided to sink down on his belly again but continued to stare at Henry. “The Pope’s armies are led by King John of Jerusalem! Queen Yolanda’s father. I wish my cousin Eschiva was here so we could talk about it,” Henry admitted. The lion was not the best conversationalist.

Since he had no other companion he trusted however, Henry soon resumed his monologue. “I overheard Herman von Salza, that’s the Master of the Teutonic Knights, who recently arrived from Acre, say that if Frederick wanted a kingdom to return to, he needed to take Jerusalem fast and return to Sicily. Frederick insisted he had to ‘crush’ the Ibelins first. Salza tried to convince him that this war on fellow Christians only played into the hands of the Pope, and warned him he might win Cyprus only at the price of losing Sicily. Then he told the Emperor, ‘Take Jerusalem and you’ll be the hero of Christendom. After that, you can do whatever you like to the Ibelins and their friends.’”

Henry paused, thinking about that. “I hope that’s not true because I don’t see why he should be able to take away people’s lands and titles just because he doesn’t like them. Beirut’s father defended Jerusalem against Saladin, you know. If it wasn’t for him, many more Christians would have been enslaved. And Beirut himself made a prosperous city out of Beirut that was a ruin before. The Emperor shouldn’t interfere in affairs here. He doesn’t understand anything about the Holy Land and those of us who were born here.”

The lion yawned again and blinked at Henry slowly.

“I don’t really think he can do Lord John and Lord Walter any harm,” Henry told the lion a little uncertainly. “They hold the royal castles, and if you’d ever seen them you’d know they are impregnable.” Henry stumbled over this word that he had only recently learned from Gunther von Falkenhayn. Then he brightened and confided to the lion, “Best of all, if Frederick goes to Syria to recapture Jerusalem, then I’ll be rid of him! The first thing I’m going to do is ride to St. Hilarion to see my sisters, and then I’m going to visit Lady Yvonne and Lady Eschiva. In fact, I think I’ll hold a tournament and have a banquet with lots of music and dancing.” Henry was warming to the theme of being master of his own house again.

The lion tentatively reached one of his big paws out between the bars of the cage as if offering it to Henry. The fur looked wonderfully soft, and the paw was relaxed and looked gentle. It was almost as if the lion was offering him friendship. Henry wanted to reach out and touch that paw, but the lion-keeper had warned him never, never, never to try to touch the lion. He claimed the lion was still wild at heart and only looking for an opportunity to take his revenge upon his captors.

Still, Henry didn’t feel any hostility emanating from the lion. The lion seemed to understand and sympathize with him. So Henry looked left and right to see if the lion-keeper was anywhere about. He appeared to be alone, but Henry knew from experience that the lion-keeper liked to keep out of sight yet within hearing. “Hello?” Henry called out to see if he got a reaction.

Although no one answered, he heard voices outside—angry, agitated voices.

Now what? Henry thought, pushing himself to his feet in anticipation of something unpleasant.

A moment later one of his Sicilian watchdogs burst in, grimacing at the smell and visibly holding his breath. “My lord! Come at once! The Emperor wishes to speak with you.”

King Henry was in his menagerie. It had always been one of his favorite places, but since the arrival of the Holy Roman Emperor, he spent more time here than usual. His Sicilian watchdogs didn’t like the stink of the big cats and made disgusted faces, preferring to stay outside in the garden when Henry visited the cats. Henry didn’t like the smell either, but he found that the longer he stayed the less he noticed it, and so, whenever he wanted to escape the company of the various imperial officials the Emperor imposed on him, he came and conversed with the lion.

“We’re in the same situation,” Henry explained, looking into the unblinking, golden eyes of the lion. “You can’t run free and be with your friends, and neither can I. But at least you don’t have to listen to lectures all day long,” Henry added. The Emperor insisted that King Henry needed more “education” and had assigned him instructors, particularly for the natural sciences and mathematics. That was bad enough, Henry felt, but what he really resented was that whenever the “the wonder of the world,” Frederick Hohenstaufen, spoke with him, the latter spent most of the time telling Henry how evil and insidious his former friends were.

“Maybe Lord Philip did keep some of my revenues for himself,” Henry told the lion, who yawned at him, letting out a puff of bad-smelling breath. “But it isn’t as if I went without anything I needed or wanted,” Henry pointed out.

The lion slowly pulled his hind feet under him and pushed himself upright. He sauntered over to the bars of his cage and looked more intently at Henry, who was sitting on the floor outside the cage with his back against the wall.

“Nor is the Emperor a particularly good king,” Henry informed the attentive lion. “If he was, then people wouldn’t keep rebelling against him. First, he drove the Lord of Beirut into rebellion by threatening to take away Beirut, and now all of Apulia is in revolt. Apulia,” Henry explained to the lion, “are the lands in Southern Italy that belong to the Kingdom of Sicily. For weeks now, messengers arrive practically every day reporting on yet another city that has either fallen or just gone over to the Pope without a fight. And you know the best of it?” Henry asked the lion, who decided to sink down on his belly again but continued to stare at Henry. “The Pope’s armies are led by King John of Jerusalem! Queen Yolanda’s father. I wish my cousin Eschiva was here so we could talk about it,” Henry admitted. The lion was not the best conversationalist.

Since he had no other companion he trusted however, Henry soon resumed his monologue. “I overheard Herman von Salza, that’s the Master of the Teutonic Knights, who recently arrived from Acre, say that if Frederick wanted a kingdom to return to, he needed to take Jerusalem fast and return to Sicily. Frederick insisted he had to ‘crush’ the Ibelins first. Salza tried to convince him that this war on fellow Christians only played into the hands of the Pope, and warned him he might win Cyprus only at the price of losing Sicily. Then he told the Emperor, ‘Take Jerusalem and you’ll be the hero of Christendom. After that, you can do whatever you like to the Ibelins and their friends.’”

Henry paused, thinking about that. “I hope that’s not true because I don’t see why he should be able to take away people’s lands and titles just because he doesn’t like them. Beirut’s father defended Jerusalem against Saladin, you know. If it wasn’t for him, many more Christians would have been enslaved. And Beirut himself made a prosperous city out of Beirut that was a ruin before. The Emperor shouldn’t interfere in affairs here. He doesn’t understand anything about the Holy Land and those of us who were born here.”

The lion yawned again and blinked at Henry slowly.

“I don’t really think he can do Lord John and Lord Walter any harm,” Henry told the lion a little uncertainly. “They hold the royal castles, and if you’d ever seen them you’d know they are impregnable.” Henry stumbled over this word that he had only recently learned from Gunther von Falkenhayn. Then he brightened and confided to the lion, “Best of all, if Frederick goes to Syria to recapture Jerusalem, then I’ll be rid of him! The first thing I’m going to do is ride to St. Hilarion to see my sisters, and then I’m going to visit Lady Yvonne and Lady Eschiva. In fact, I think I’ll hold a tournament and have a banquet with lots of music and dancing.” Henry was warming to the theme of being master of his own house again.

The lion tentatively reached one of his big paws out between the bars of the cage as if offering it to Henry. The fur looked wonderfully soft, and the paw was relaxed and looked gentle. It was almost as if the lion was offering him friendship. Henry wanted to reach out and touch that paw, but the lion-keeper had warned him never, never, never to try to touch the lion. He claimed the lion was still wild at heart and only looking for an opportunity to take his revenge upon his captors.

Still, Henry didn’t feel any hostility emanating from the lion. The lion seemed to understand and sympathize with him. So Henry looked left and right to see if the lion-keeper was anywhere about. He appeared to be alone, but Henry knew from experience that the lion-keeper liked to keep out of sight yet within hearing. “Hello?” Henry called out to see if he got a reaction.

Although no one answered, he heard voices outside—angry, agitated voices.

Now what? Henry thought, pushing himself to his feet in anticipation of something unpleasant.

A moment later one of his Sicilian watchdogs burst in, grimacing at the smell and visibly holding his breath. “My lord! Come at once! The Emperor wishes to speak with you.”

Published on October 19, 2018 02:00

Rebels against Tyranny - The Loneliness of Kings

With the arrival of Emperor Frederick in Cyprus, King Henry was isolated from his previous advisors and became a virtual prisoner of the Hohenstaufen's men. He was treated courteously -- but like a puppet. His later behavior suggests just how much he came to hate both Frederick and his local supporters. In this scene the nine-year-old monarch reflects on his position with his only sympathetic companion: the lion in his menagerie.

King Henry was in his menagerie. It had always been one of his favorite places, but since the arrival of the Holy Roman Emperor, he spent more time here than usual. His Sicilian watchdogs didn’t like the stink of the big cats and made disgusted faces, preferring to stay outside in the garden when Henry visited the cats. Henry didn’t like the smell either, but he found that the longer he stayed the less he noticed it, and so, whenever he wanted to escape the company of the various imperial officials the Emperor imposed on him, he came and conversed with the lion.

“We’re in the same situation,” Henry explained, looking into the unblinking, golden eyes of the lion. “You can’t run free and be with your friends, and neither can I. But at least you don’t have to listen to lectures all day long,” Henry added. The Emperor insisted that King Henry needed more “education” and had assigned him instructors, particularly for the natural sciences and mathematics. That was bad enough, Henry felt, but what he really resented was that whenever the “the wonder of the world,” Frederick Hohenstaufen, spoke with him, the latter spent most of the time telling Henry how evil and insidious his former friends were.

“Maybe Lord Philip did keep some of my revenues for himself,” Henry told the lion, who yawned at him, letting out a puff of bad-smelling breath. “But it isn’t as if I went without anything I needed or wanted,” Henry pointed out.

The lion slowly pulled his hind feet under him and pushed himself upright. He sauntered over to the bars of his cage and looked more intently at Henry, who was sitting on the floor outside the cage with his back against the wall.

“Nor is the Emperor a particularly good king,” Henry informed the attentive lion. “If he was, then people wouldn’t keep rebelling against him. First, he drove the Lord of Beirut into rebellion by threatening to take away Beirut, and now all of Apulia is in revolt. Apulia,” Henry explained to the lion, “are the lands in Southern Italy that belong to the Kingdom of Sicily. For weeks now, messengers arrive practically every day reporting on yet another city that has either fallen or just gone over to the Pope without a fight. And you know the best of it?” Henry asked the lion, who decided to sink down on his belly again but continued to stare at Henry. “The Pope’s armies are led by King John of Jerusalem! Queen Yolanda’s father. I wish my cousin Eschiva was here so we could talk about it,” Henry admitted. The lion was not the best conversationalist.

Since he had no other companion he trusted however, Henry soon resumed his monologue. “I overheard Herman von Salza, that’s the Master of the Teutonic Knights, who recently arrived from Acre, say that if Frederick wanted a kingdom to return to, he needed to take Jerusalem fast and return to Sicily. Frederick insisted he had to ‘crush’ the Ibelins first. Salza tried to convince him that this war on fellow Christians only played into the hands of the Pope, and warned him he might win Cyprus only at the price of losing Sicily. Then he told the Emperor, ‘Take Jerusalem and you’ll be the hero of Christendom. After that, you can do whatever you like to the Ibelins and their friends.’”

Henry paused, thinking about that. “I hope that’s not true because I don’t see why he should be able to take away people’s lands and titles just because he doesn’t like them. Beirut’s father defended Jerusalem against Saladin, you know. If it wasn’t for him, many more Christians would have been enslaved. And Beirut himself made a prosperous city out of Beirut that was a ruin before. The Emperor shouldn’t interfere in affairs here. He doesn’t understand anything about the Holy Land and those of us who were born here.”

The lion yawned again and blinked at Henry slowly.

“I don’t really think he can do Lord John and Lord Walter any harm,” Henry told the lion a little uncertainly. “They hold the royal castles, and if you’d ever seen them you’d know they are impregnable.” Henry stumbled over this word that he had only recently learned from Gunther von Falkenhayn. Then he brightened and confided to the lion, “Best of all, if Frederick goes to Syria to recapture Jerusalem, then I’ll be rid of him! The first thing I’m going to do is ride to St. Hilarion to see my sisters, and then I’m going to visit Lady Yvonne and Lady Eschiva. In fact, I think I’ll hold a tournament and have a banquet with lots of music and dancing.” Henry was warming to the theme of being master of his own house again.

The lion tentatively reached one of his big paws out between the bars of the cage as if offering it to Henry. The fur looked wonderfully soft, and the paw was relaxed and looked gentle. It was almost as if the lion was offering him friendship. Henry wanted to reach out and touch that paw, but the lion-keeper had warned him never, never, never to try to touch the lion. He claimed the lion was still wild at heart and only looking for an opportunity to take his revenge upon his captors.

Still, Henry didn’t feel any hostility emanating from the lion. The lion seemed to understand and sympathize with him. So Henry looked left and right to see if the lion-keeper was anywhere about. He appeared to be alone, but Henry knew from experience that the lion-keeper liked to keep out of sight yet within hearing. “Hello?” Henry called out to see if he got a reaction.

Although no one answered, he heard voices outside—angry, agitated voices.

Now what? Henry thought, pushing himself to his feet in anticipation of something unpleasant.

A moment later one of his Sicilian watchdogs burst in, grimacing at the smell and visibly holding his breath. “My lord! Come at once! The Emperor wishes to speak with you.”

King Henry was in his menagerie. It had always been one of his favorite places, but since the arrival of the Holy Roman Emperor, he spent more time here than usual. His Sicilian watchdogs didn’t like the stink of the big cats and made disgusted faces, preferring to stay outside in the garden when Henry visited the cats. Henry didn’t like the smell either, but he found that the longer he stayed the less he noticed it, and so, whenever he wanted to escape the company of the various imperial officials the Emperor imposed on him, he came and conversed with the lion.

“We’re in the same situation,” Henry explained, looking into the unblinking, golden eyes of the lion. “You can’t run free and be with your friends, and neither can I. But at least you don’t have to listen to lectures all day long,” Henry added. The Emperor insisted that King Henry needed more “education” and had assigned him instructors, particularly for the natural sciences and mathematics. That was bad enough, Henry felt, but what he really resented was that whenever the “the wonder of the world,” Frederick Hohenstaufen, spoke with him, the latter spent most of the time telling Henry how evil and insidious his former friends were.

“Maybe Lord Philip did keep some of my revenues for himself,” Henry told the lion, who yawned at him, letting out a puff of bad-smelling breath. “But it isn’t as if I went without anything I needed or wanted,” Henry pointed out.

The lion slowly pulled his hind feet under him and pushed himself upright. He sauntered over to the bars of his cage and looked more intently at Henry, who was sitting on the floor outside the cage with his back against the wall.

“Nor is the Emperor a particularly good king,” Henry informed the attentive lion. “If he was, then people wouldn’t keep rebelling against him. First, he drove the Lord of Beirut into rebellion by threatening to take away Beirut, and now all of Apulia is in revolt. Apulia,” Henry explained to the lion, “are the lands in Southern Italy that belong to the Kingdom of Sicily. For weeks now, messengers arrive practically every day reporting on yet another city that has either fallen or just gone over to the Pope without a fight. And you know the best of it?” Henry asked the lion, who decided to sink down on his belly again but continued to stare at Henry. “The Pope’s armies are led by King John of Jerusalem! Queen Yolanda’s father. I wish my cousin Eschiva was here so we could talk about it,” Henry admitted. The lion was not the best conversationalist.

Since he had no other companion he trusted however, Henry soon resumed his monologue. “I overheard Herman von Salza, that’s the Master of the Teutonic Knights, who recently arrived from Acre, say that if Frederick wanted a kingdom to return to, he needed to take Jerusalem fast and return to Sicily. Frederick insisted he had to ‘crush’ the Ibelins first. Salza tried to convince him that this war on fellow Christians only played into the hands of the Pope, and warned him he might win Cyprus only at the price of losing Sicily. Then he told the Emperor, ‘Take Jerusalem and you’ll be the hero of Christendom. After that, you can do whatever you like to the Ibelins and their friends.’”

Henry paused, thinking about that. “I hope that’s not true because I don’t see why he should be able to take away people’s lands and titles just because he doesn’t like them. Beirut’s father defended Jerusalem against Saladin, you know. If it wasn’t for him, many more Christians would have been enslaved. And Beirut himself made a prosperous city out of Beirut that was a ruin before. The Emperor shouldn’t interfere in affairs here. He doesn’t understand anything about the Holy Land and those of us who were born here.”

The lion yawned again and blinked at Henry slowly.

“I don’t really think he can do Lord John and Lord Walter any harm,” Henry told the lion a little uncertainly. “They hold the royal castles, and if you’d ever seen them you’d know they are impregnable.” Henry stumbled over this word that he had only recently learned from Gunther von Falkenhayn. Then he brightened and confided to the lion, “Best of all, if Frederick goes to Syria to recapture Jerusalem, then I’ll be rid of him! The first thing I’m going to do is ride to St. Hilarion to see my sisters, and then I’m going to visit Lady Yvonne and Lady Eschiva. In fact, I think I’ll hold a tournament and have a banquet with lots of music and dancing.” Henry was warming to the theme of being master of his own house again.

The lion tentatively reached one of his big paws out between the bars of the cage as if offering it to Henry. The fur looked wonderfully soft, and the paw was relaxed and looked gentle. It was almost as if the lion was offering him friendship. Henry wanted to reach out and touch that paw, but the lion-keeper had warned him never, never, never to try to touch the lion. He claimed the lion was still wild at heart and only looking for an opportunity to take his revenge upon his captors.

Still, Henry didn’t feel any hostility emanating from the lion. The lion seemed to understand and sympathize with him. So Henry looked left and right to see if the lion-keeper was anywhere about. He appeared to be alone, but Henry knew from experience that the lion-keeper liked to keep out of sight yet within hearing. “Hello?” Henry called out to see if he got a reaction.

Although no one answered, he heard voices outside—angry, agitated voices.

Now what? Henry thought, pushing himself to his feet in anticipation of something unpleasant.

A moment later one of his Sicilian watchdogs burst in, grimacing at the smell and visibly holding his breath. “My lord! Come at once! The Emperor wishes to speak with you.”

Published on October 19, 2018 02:00

October 12, 2018

The Emperor's Letter - An Excerpt from Rebels against Tyranny

When Emperor Frederick II arrived in Limassol on his way to the Holy Land for his repeatedly promised and long-delayed crusade, he sent to his "beloved uncle" John d'Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, a letter full of assurances of affection and high regard. In the letter, he begged the Lord of Beirut to bring his children to Limassol so that the Emperor might embrace them and promised Beirut himself rich rewards. Beirut's friends and advisors, however, smelled a rat and warned him not to accept the Emperor's invitation.

In this scene, Beirut's children debate what he should do.

“Won’t any of you support me in this?” Balian demanded of his siblings furiously as soon as they were alone together. “The Emperor intends to humiliate and ruin our father! He told me to my face that he would hold him accountable for Uncle Philip ‘plundering’ the royal Cypriot treasury—and that was before Barlais started filling his ear with further lies.”

“That’s what you keep saying, but the Emperor’s letter spoke a very different message,” Baldwin pointed out in an annoyed tone.

“Didn’t you hear what everyone in there was saying?” Balian countered incredulously. “Everyone agreed the letter was suspicious! The Emperor’s letters have more often been filled with lies than truth! He lied to King John, he lied to the Pope, he lied to the Lombard League, he lied to the German princes! His reign is a catalog of broken promises. Starting with a crusading vow that he’s deferred so many times I lost track! The Patriarch of Jerusalem warned against any association with the Hohenstaufen.”

“Don’t let yourself get dragged into Church affairs, Bal,” Hugh advised. “The Emperor’s dispute with the papacy has nothing to do with us. The Pope tried to stop this crusade even though it’s the best chance we’ve had of regaining Jerusalem since Richard the Lionheart went home.”

“That’s not the point,” Balian argued. “You’ve got to understand how often Frederick has said one thing and done the opposite! If this is supposed to be a crusade, why the hell did the Holy Roman Emperor bring more scholars and clerics than fighting men? Why did he bring his harem?”

“Oh, come on!” Baldwin rolled his eyes. “You don’t have to lower yourself to repeating convent-girl gossip!”

“Damn it, Baldwin!” Balian lashed out at his brother furiously. “I saw them with my own eyes!”

“Really? Harem girls?” Hugh pricked up his ears and looked like a bird-dog ready to pounce. “I’d like to see them.”

“They were veiled, of course,” Balian tossed at Hugh, deflating his interest a little, “but there were about a dozen of them. Furthermore, they were escorted off one of Fredrick’s ships by a score of Mamlukes—probably eunuchs—in turbans and Saracen sashes. I could hardly believe my eyes so I asked one of the sailors about them. He told me they were Sicilian Muslims who served the Emperor as his personal bodyguard—and the bodyguard of his harem it seems—just like our cousin Eschiva tried to tell us. This is not a man who is the least bit serious about a crusade! He’s here for no other purpose than to exert his authority over us—the lords of Cyprus and Jerusalem! You’ve got to believe me!” Balian was starting to feel desperate.

“I agree with you, Balian,” Bella spoke up, startling her brothers. “Frederick isn’t much of a fighter, but he’s obsessed with his power and position.”

“Just what makes you, of all people, an expert on the Holy Roman Emperor?” Baldwin wanted to know.

“I’m the one who talked to cousin Eschiva most, and she spent three years at his court,” Bella told him bluntly, staring him down.

“Eschiva? You should have heard the way her brother talked about her! She’s not a reliable witness,” Baldwin said dismissively, earning the immediate ire of both Balian and Bella.

Balian rose to Eschiva’s defense “She’s a far more reliable witness than Eudes is! Eudes is so wrapped up in his own importance and self-interest he wouldn’t be able to see a rabid dog if it was standing three feet in front of him.”

Bella insisted belligerently, “Eschiva is very perceptive and intelligent, and she saw the callous and cold-blooded way Frederick treated his bride—which is why all that talk about ‘dear and well-beloved cousins,’ and ‘affectionate’ feelings for Papa is fake. Think about it, Baldwin! Why on earth would the Emperor want Papa to bring ‘his children’ with him on crusade? He seemed far more interested in us than in the King—which is very suspicious.”

“We happen to be some of the best knights—” Hugh started to point out.

“Spare me!” Bella cut him off. “The Emperor didn’t say ‘adult sons’ or ‘knighted sons,’ he said ‘your children,’—which, by the way, included Johnny and Guy and me!”

“And you will stay right here in Nicosia with the King’s sisters,” John of Beirut ordered firmly, coming into the room and bringing his sons to their feet respectfully.

“Father, we need to talk,” Balian declared at once, only to break off when his father shook his head.

“Balian, I know what you think and feel. You’ve told me often enough already.”

“Father, listen to me! Frederick is surrounded by Muslims and Jews.”

“And four archbishops,” his father reminded him.

“Four Sicilian Archbishops, who are about as spirited as donkeys!”

“Balian! Please! I don’t like to hear you talk that way about princes of the Church. Calm down, and listen to me instead. We don’t need to discuss it again because this letter gave your suspicions more credence than anything more you could say. Bella, sharp as she is,” Beirut smiled at his daughter with genuine pride, “put her finger on it. This insistence on me bringing my children is alarming. You and Hugh are also right: the letter reeks of nauseating flattery. His assurances of affection for the ‘uncle’ of a bride he treated hardly better than a slave girl ring very hollow indeed. I do not believe for a moment that the Emperor intends to seek my advice much less honor me in any way.” He paused to let his words sink in, and Balian was humbled by his father’s clear understanding of the situation.

“That said, I was not being melodramatic when I said I would rather die than be accused of undermining this crusade. Your grandfather spent his entire life in the service of Jerusalem. He gave everything for Jerusalem—offering his own freedom to ransom the poor. I, in contrast, have done nothing but enrich myself. I have rebuilt a city and built a splendid palace. By the grace of God, I have six fine children and have seen them educated and outfitted in the most lavish manner possible. I am one of the wealthiest and most powerful men this side of the sea. Many men in Outremer follow my lead and my example. If I fail to respond to the Emperor’s summons, then men will be right to say that I am nothing but a wealthy, ambitious and self-serving man.”

“But he’s hardly brought any troops himself!” Balian protested again. “

All the more reason that we must come with our full strength,” his father countered. “You,” he looked to Balian, but then included Bella and Hugh, “however, are right that there is good reason to doubt the Emperor’s intentions. So we must all be on the alert, but the men of the House of Ibelin will go to meet the Emperor, while Bella remains here. Understood?” He looked from one child to the other, receiving a “Yes, my lord,” from all his children.

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

In this scene, Beirut's children debate what he should do.

“Won’t any of you support me in this?” Balian demanded of his siblings furiously as soon as they were alone together. “The Emperor intends to humiliate and ruin our father! He told me to my face that he would hold him accountable for Uncle Philip ‘plundering’ the royal Cypriot treasury—and that was before Barlais started filling his ear with further lies.”

“That’s what you keep saying, but the Emperor’s letter spoke a very different message,” Baldwin pointed out in an annoyed tone.

“Didn’t you hear what everyone in there was saying?” Balian countered incredulously. “Everyone agreed the letter was suspicious! The Emperor’s letters have more often been filled with lies than truth! He lied to King John, he lied to the Pope, he lied to the Lombard League, he lied to the German princes! His reign is a catalog of broken promises. Starting with a crusading vow that he’s deferred so many times I lost track! The Patriarch of Jerusalem warned against any association with the Hohenstaufen.”

“Don’t let yourself get dragged into Church affairs, Bal,” Hugh advised. “The Emperor’s dispute with the papacy has nothing to do with us. The Pope tried to stop this crusade even though it’s the best chance we’ve had of regaining Jerusalem since Richard the Lionheart went home.”

“That’s not the point,” Balian argued. “You’ve got to understand how often Frederick has said one thing and done the opposite! If this is supposed to be a crusade, why the hell did the Holy Roman Emperor bring more scholars and clerics than fighting men? Why did he bring his harem?”

“Oh, come on!” Baldwin rolled his eyes. “You don’t have to lower yourself to repeating convent-girl gossip!”

“Damn it, Baldwin!” Balian lashed out at his brother furiously. “I saw them with my own eyes!”

“Really? Harem girls?” Hugh pricked up his ears and looked like a bird-dog ready to pounce. “I’d like to see them.”

“They were veiled, of course,” Balian tossed at Hugh, deflating his interest a little, “but there were about a dozen of them. Furthermore, they were escorted off one of Fredrick’s ships by a score of Mamlukes—probably eunuchs—in turbans and Saracen sashes. I could hardly believe my eyes so I asked one of the sailors about them. He told me they were Sicilian Muslims who served the Emperor as his personal bodyguard—and the bodyguard of his harem it seems—just like our cousin Eschiva tried to tell us. This is not a man who is the least bit serious about a crusade! He’s here for no other purpose than to exert his authority over us—the lords of Cyprus and Jerusalem! You’ve got to believe me!” Balian was starting to feel desperate.

“I agree with you, Balian,” Bella spoke up, startling her brothers. “Frederick isn’t much of a fighter, but he’s obsessed with his power and position.”

“Just what makes you, of all people, an expert on the Holy Roman Emperor?” Baldwin wanted to know.

“I’m the one who talked to cousin Eschiva most, and she spent three years at his court,” Bella told him bluntly, staring him down.

“Eschiva? You should have heard the way her brother talked about her! She’s not a reliable witness,” Baldwin said dismissively, earning the immediate ire of both Balian and Bella.

Balian rose to Eschiva’s defense “She’s a far more reliable witness than Eudes is! Eudes is so wrapped up in his own importance and self-interest he wouldn’t be able to see a rabid dog if it was standing three feet in front of him.”

Bella insisted belligerently, “Eschiva is very perceptive and intelligent, and she saw the callous and cold-blooded way Frederick treated his bride—which is why all that talk about ‘dear and well-beloved cousins,’ and ‘affectionate’ feelings for Papa is fake. Think about it, Baldwin! Why on earth would the Emperor want Papa to bring ‘his children’ with him on crusade? He seemed far more interested in us than in the King—which is very suspicious.”

“We happen to be some of the best knights—” Hugh started to point out.

“Spare me!” Bella cut him off. “The Emperor didn’t say ‘adult sons’ or ‘knighted sons,’ he said ‘your children,’—which, by the way, included Johnny and Guy and me!”

“And you will stay right here in Nicosia with the King’s sisters,” John of Beirut ordered firmly, coming into the room and bringing his sons to their feet respectfully.

“Father, we need to talk,” Balian declared at once, only to break off when his father shook his head.

“Balian, I know what you think and feel. You’ve told me often enough already.”

“Father, listen to me! Frederick is surrounded by Muslims and Jews.”

“And four archbishops,” his father reminded him.

“Four Sicilian Archbishops, who are about as spirited as donkeys!”

“Balian! Please! I don’t like to hear you talk that way about princes of the Church. Calm down, and listen to me instead. We don’t need to discuss it again because this letter gave your suspicions more credence than anything more you could say. Bella, sharp as she is,” Beirut smiled at his daughter with genuine pride, “put her finger on it. This insistence on me bringing my children is alarming. You and Hugh are also right: the letter reeks of nauseating flattery. His assurances of affection for the ‘uncle’ of a bride he treated hardly better than a slave girl ring very hollow indeed. I do not believe for a moment that the Emperor intends to seek my advice much less honor me in any way.” He paused to let his words sink in, and Balian was humbled by his father’s clear understanding of the situation.

“That said, I was not being melodramatic when I said I would rather die than be accused of undermining this crusade. Your grandfather spent his entire life in the service of Jerusalem. He gave everything for Jerusalem—offering his own freedom to ransom the poor. I, in contrast, have done nothing but enrich myself. I have rebuilt a city and built a splendid palace. By the grace of God, I have six fine children and have seen them educated and outfitted in the most lavish manner possible. I am one of the wealthiest and most powerful men this side of the sea. Many men in Outremer follow my lead and my example. If I fail to respond to the Emperor’s summons, then men will be right to say that I am nothing but a wealthy, ambitious and self-serving man.”

“But he’s hardly brought any troops himself!” Balian protested again. “

All the more reason that we must come with our full strength,” his father countered. “You,” he looked to Balian, but then included Bella and Hugh, “however, are right that there is good reason to doubt the Emperor’s intentions. So we must all be on the alert, but the men of the House of Ibelin will go to meet the Emperor, while Bella remains here. Understood?” He looked from one child to the other, receiving a “Yes, my lord,” from all his children.

BUY NOW!

BUY NOW!

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight into historical events and figures based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.

Published on October 12, 2018 02:00

Rebels against Tyranny - The Emperor's Letter

When Emperor Frederick II arrived in Limassol on his way to the Holy Land for his repeatedly promised and long-delayed crusade, he sent to his "beloved uncle" John d'Ibelin, Lord of Beirut, a letter full of assurances of affection and high regard. In the letter, he begged the Lord of Beirut to bring his children to Limassol so that the Emperor might embrace them and promised Beirut himself rich rewards. Beirut's friends and advisors, however, smelled a rat and warned him not to accept the Emperor's invitation.

In this scene, Beirut's children debate what he should do.

“Won’t any of you support me in this?” Balian demanded of his siblings furiously as soon as they were alone together. “The Emperor intends to humiliate and ruin our father! He told me to my face that he would hold him accountable for Uncle Philip ‘plundering’ the royal Cypriot treasury—and that was before Barlais started filling his ear with further lies.”

“That’s what you keep saying, but the Emperor’s letter spoke a very different message,” Baldwin pointed out in an annoyed tone.

“Didn’t you hear what everyone in there was saying?” Balian countered incredulously. “Everyone agreed the letter was suspicious! The Emperor’s letters have more often been filled with lies than truth! He lied to King John, he lied to the Pope, he lied to the Lombard League, he lied to the German princes! His reign is a catalog of broken promises. Starting with a crusading vow that he’s deferred so many times I lost track! The Patriarch of Jerusalem warned against any association with the Hohenstaufen.”

“Don’t let yourself get dragged into Church affairs, Bal,” Hugh advised. “The Emperor’s dispute with the papacy has nothing to do with us. The Pope tried to stop this crusade even though it’s the best chance we’ve had of regaining Jerusalem since Richard the Lionheart went home.”

“That’s not the point,” Balian argued. “You’ve got to understand how often Frederick has said one thing and done the opposite! If this is supposed to be a crusade, why the hell did the Holy Roman Emperor bring more scholars and clerics than fighting men? Why did he bring his harem?”

“Oh, come on!” Baldwin rolled his eyes. “You don’t have to lower yourself to repeating convent-girl gossip!”

“Damn it, Baldwin!” Balian lashed out at his brother furiously. “I saw them with my own eyes!”

“Really? Harem girls?” Hugh pricked up his ears and looked like a bird-dog ready to pounce. “I’d like to see them.”

“They were veiled, of course,” Balian tossed at Hugh, deflating his interest a little, “but there were about a dozen of them. Furthermore, they were escorted off one of Fredrick’s ships by a score of Mamlukes—probably eunuchs—in turbans and Saracen sashes. I could hardly believe my eyes so I asked one of the sailors about them. He told me they were Sicilian Muslims who served the Emperor as his personal bodyguard—and the bodyguard of his harem it seems—just like our cousin Eschiva tried to tell us. This is not a man who is the least bit serious about a crusade! He’s here for no other purpose than to exert his authority over us—the lords of Cyprus and Jerusalem! You’ve got to believe me!” Balian was starting to feel desperate.

“I agree with you, Balian,” Bella spoke up, startling her brothers. “Frederick isn’t much of a fighter, but he’s obsessed with his power and position.”

“Just what makes you, of all people, an expert on the Holy Roman Emperor?” Baldwin wanted to know.

“I’m the one who talked to cousin Eschiva most, and she spent three years at his court,” Bella told him bluntly, staring him down.

“Eschiva? You should have heard the way her brother talked about her! She’s not a reliable witness,” Baldwin said dismissively, earning the immediate ire of both Balian and Bella.

Balian rose to Eschiva’s defense “She’s a far more reliable witness than Eudes is! Eudes is so wrapped up in his own importance and self-interest he wouldn’t be able to see a rabid dog if it was standing three feet in front of him.”