Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 16

February 24, 2022

Review: Because it is Absurd by Pierre Boulle

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

Julliard, 1966

Julliard, 1966

translated by Elisabeth Abbott

Vanguard Press, 1971

190 pages

The full title of this collection is Because it is Absurd (on Earth as in Heaven), and if that sounds familiar to you, that’s because it riffs off of Jesus’s words in Matthew 6:10: “Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” (Thank goodness I have a Catholic husband to point out these things to me!) As Boulle’s biographer Lucille Becker has noted, “[d]espite his own professed lack of belief…, Boulle’s Catholic education is evident in much of his work” (Pierre Boulle, 97-8). Because it is Absurd, is, in some ways, the most explicitly religious of his books thus far, including angels, Eden, God, Jesus, and more.

The first four stories in the collection (“On Earth”) take up everything from Hitler alive and well in Peru in the 1970s (“His Last Battle”) to a disgraced man hiring his own murderer (“Interferences”). Only the former (of all four stories) could be considered speculative, since it’s an alternate history. The three subsequent stories (“As in Heaven”) are much more interesting and strange, imagining (among other things) the Garden of Eden as a kind of universal franchise and angels destroying all of the holy places in Jerusalem in order to end religious warfare forever.

In general, this collection is something of a hodge-podge, which unfortunately takes the sparkle out of those stories that truly stand out. Indeed, it’s those tales in the second half of the book that are the most interesting, so my review will focus on them.

“When the Serpent Failed” starts off small and ends up encompassing the whole universe. Here, Boulle reimagines the Biblical creation story of Adam and Eve. What would have happened had Eve said “nah” to the serpent when enticed to eat the apple from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil? Bad, bad things, apparently. As per usual when it comes to Boulle, the most commonplace things, when taken to their logical conclusions, become completely absurd. So Eve says “no, thank you” and the serpent is like “wait, what?” so he obviously turns to God for next steps. But then God turns to (I kid you not) the Holy Computer to ask what should be done. The three huddle up and imagine a million different ways to entice Eve to eat the apple. After all, the other 2,999,999 Eves on 2,999,999 other inhabited planets took that juicy bite and everything went according to plan. This one sassy Eve, though, isn’t falling for the serpent’s wiles. But what happens, then, if Adam and Eve remain “innocent” of good and evil and stay immortal, but still procreate and build new things and eventually head out into the universe? According to Boulle, this human race would become an amoral horde that would wipe out the other planets’ populations and replace them. So when the three finally find themselves stumped, they let Jesus take a crack at the problem. Jesus is like “guys, you’re overthinking this” and comes up with a simple but foolproof plan to bring Eve back into line.

And if you thought that “Holy Computer” sounded a bit Stanislaw-Lem-ish, you’re be absolutely right.

“The Holy Places,” while an interesting idea, seems rushed and could have actually been a much better, longer story. Here, “J” (Jesus), “Y” (Yahwh), and “A” (Allah) direct their angels to raze all of the holy sites in Jerusalem. Not just raze them, ohhhh no, but pulverize them so that nothing, absolutely nothing is left. That way, they believe, humans will just throw up their hands and stop fighting religious wars. Also, guess who shows up again? That’s right: the Holy Computer. Well, in this story, it’s called the “Great” Computer, but same thing. I wasn’t convinced, but like I said–an interesting story idea.

And then we have “The Heart and the Galaxy” (1970, tr. 1971) which I’d call a lighter, more humorous version of Lem’s dead-serious masterpiece His Master’s Voice (1968, tr. 1983). Both concern humans desperately waiting for a signal from an alien intelligence and, when they receive a signal, they pounce upon it in order to decipher it. In Boulle’s story, scientists wait on the dark side of the moon in a place called the “Cosmos Observatory” in hopes of hearing a signal. As Boulle does in many other stories, he ratchets up the tension until the very last page. The scientists go nuts when they think they’ve intercepted alien communication (from 40,000 light years away), and when they calm down, realize that the aliens are trying to teach them their language via binary code. The scientists set up a complicated grid and follow the aliens’ instructions, eventually deciphering a message that…well, I won’t spoil it for you (wink, wink).

So if I had been Boulle’s editor, I would’ve told him to include “When the Serpent Failed” in Time Out of Mind and expand “The Heart and the Galaxy” into at least a novella. As it stands, though, Because it is Absurd is a wild ride.

I find myself saying that a lot in my Boulle reviews…

February 17, 2022

Review: Garden on the Moon by Pierre Boulle

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

Julliard, 1964

Julliard, 1964

translated by Xan Fielding

Vanguard Press, 1965

315 pages

Boulle’s third book to be translated into English demonstrates the writer’s gift for creating heightened tension in the plot and then easing it with a heavy dose of irony. And if you like learning about the space race of the 1950s and 60s, you’ll love this book.

Garden on the Moon is a unique tale in that it begins as fictionalized history and then turns into, what was for Boulle, speculative fiction but what is, for us now in 2022, alternative history. I know–it’s a bit confusing. In his introduction, Boulle explains that the last thing he wants to do is write about the near future and then have that future turn out so differently in his lifetime that his book is dismissed or ridiculed. While writing the book, which includes several real-life figures such as JFK, Hitler, and Stalin, Boulle heard that the former had been assassinated, thus prompting him to revise parts of the story. Nonetheless, the race to the moon was real in the early Cold War era and it was anyone’s guess who would get there first (the Americans? the Russians? another country?). So what that Boulle’s guess didn’t turn out to be the right one? I actually think he was counting on it.

The moon landing in 1969 was not that long ago, though to those of us born at least a decade after that event, it seems like forever. The video is grainy, the technology seems dated, and we’ve now had several decades of Star Trek, Star Wars, and numerous other visually-engaging science fiction shows and movies. I remember watching the video of Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon, after I had already been watching Star Trek: TNG for years, and trying to imagine what it must have felt like for my mom, dad, grandparents, and the millions of others who watched it on television that day in 1969. For Pierre Boulle, writing Garden on the Moon in 1963-64, humans still hadn’t reached that natural satellite, and no one could be sure that we ever would. And yet, Boulle offers us an idea of what might have happened, had Japan entered the space race alongside the US and USSR.

Though Boulle changed the names of characters, it’s clear that the main character Dr. Stern is none other than Dr. Wernher von Braun, who helped develop Germany’s, and then the United States’, rocket technology. Like von Braun, Stern directs research and development under the Nazi regime at a test site called Peenemünde, where he ostensibly works on rockets that can hit England and the United States, while his real goal is to develop rockets that can land humans on the moon and Mars and return them to Earth.

When the Americans and Soviets converge on Berlin, Stern (like von Braun) surrenders to the Americans, believing that their funding and commitment to the space race with Russia will mean opportunities to finally realize his ultimate goal of landing on the moon. Once more, Stern finds himself stymied by bureaucracy and parsimony. His fellow scientists from Peenemünde and elsewhere go to Japan, Russia, France, and Egypt, though they meet up frequently at aerospace conferences and exchange ideas (which I bet their governments wouldn’t have liked!). And when the Soviets launch the first man-made satellite into orbit, Stern goes…a bit ballistic.

While the book mostly follows Stern in his increasingly obsessive efforts to beat the Soviets to the moon, parts of it are longer than necessary (Boulle’s editor could have been a bit more heavy-handed, is all I’m saying, former editor that I am). Sometimes Boulle drops us in the minds of Russian scientists, sometimes in that of the Japanese aerospace engineer Dr. Kanashima. In the vein of all good unexpected endings, it is the scientist we are least likely to expect who stuns the world and reaches the moon first–all because he came up with a radical solution to the decades-old problem of how to return the astronauts from the moon to Earth.

As in his other stories and novels, Boulle takes care to remind us that the structures that serve as the visuals of scientific achievement (rockets, engines, capsules, etc.) bear a striking resemblance to the magnificent cathedrals and temples of previous centuries; scientific drive, Boulle suggests, isn’t a whole lot different than religious fervor:

[Stern] forced himself to close his eyes and recovered a little composure, shaking off the romantic images that the Peenemünde staff was only too inclined to evoke in connection with rockets: obelisk, church steeple, cathedral spire. (16)

The satellite in its dazzling gold plate had been carried onto the pad by the admiral himself. Opening its case, he raised the fragile instrument into the air at arm’s length, like a priest consecrating the Host. (137-38).

The final scenes (on the moon!) have a deliberately poetic quality and reveal Boulle’s deep interest in getting the facts right (as they were known at the time) and blending them with plausible and dream-like imagery that lines up with humanity’s centuries-long romanticization of that beloved natural satellite of ours. So while Garden on the Moon tries to do a lot of things, its underlying curiosity about the future of humanity and optimism (mixed with irony) about the future is understandably engaging.

February 11, 2022

Review: Time Out of Mind and Other Stories by Pierre Boulle

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

selected and translated by Xan Fielding

Secker & Warburg, 1966

254 pages

It’s a bit confusing when you try to sort out exactly which of Boulle’s stories from which English edition of Time Out of Mind first appeared in which French collection.* Here’s a handy list:

from Contes de l’absurde, 1953 (5 stories)

“The Age of Wisdom” (Le règne des sages)“Time Out of Mind” (Une nuit interminable)“The Perfect Robot” (Le parfait robot)from E=mc², 1957 (4 stories)

“The Miracle” (Le miracle)“The Lunians” (Les Luniens)All but one (“The Age of Wisdom”) of the above was included in the eight stories of Contes de l’absurde suivis de E=mc², 1963. In 1966, Vanguard published Time Out of Mind and Other Stories, which listed both Xan Fielding and Elisabeth Abbott as the translators and included twelve total stories. The Secker & Warburg edition of the same year includes all of these stories but three (“E=mc²,” “Love and Gravity,” and “The Hallucination”). “The Diabolical Weapon” and “The Man Who Hated Machines,” both from 1965, come from another Boulle collection, Histoires charitables. I admire anyone who can keep all of that straight.

For the rest of us, here’s the list of stories in the 1966 Secker & Warburg edition that I read (not including the two non-speculative stories):

“Time Out of Mind”“The Miracle”“The Perfect Robot”“The Lunians”“The Diabolical Weapon”“The Age of Wisdom”“The Man Who Hated Machines”* * *

I love reading an author’s short stories alongside their novels because you get to see the germs of their ideas. Boulle, in particular, keeps coming back to the clash between religion and science, the absurdity of human endeavors, and the fuzzy line between humans and machines. As in his novels, ideas and not characters drive Boulle’s stories, for in each he makes a point about human nature generally, not the individual desires and motivations that drive specific people in specific circumstances.

“Time Out of Mind,” one of Boulle’s most famous short stories and the only one in this edition to discuss time travel, takes on paradox with a hefty dose of humor. It tells of one Oscar Vincent, a bachelor and bookstore owner in Montparnasse who just wants to people-watch and drink some beer on a summer evening. Suddenly, he spots a dude in a red toga who looks lost, and then things get crazy. When Vincent asks toga-man if he needs help, the former learns that this guy is actually from an ancient civilization that has learned how to travel though time. To make things weirder, both men then notice a strange-looking dude sitting near them who seems to be listening intently to their conversation. This guy eventually comes up to the two new friends and explains that he is from the far future. Poor Vincent then becomes embroiled in what turns out to be a deadly fight between past-dude and future-dude, in which each travels forward and backward in time, trying to stop the other from successfully traveling in time. Absurdity ensues, but my favorite part is when Vincent notes that the bartender views all of these time flashes and guys appearing in weird outfits with perfect equanimity, verging on boredom. I could easily see this story as a Monty Python skit.

Boulle especially loves taking ideas to their logical and thus often absurd conclusions, and thus we have “The Lunians,” “The Diabolical Weapon,” and “The Age of Wisdom.” “The Lunians,” though a bit heavy-handed, tells the humorous story of two groups of astronauts secretly landing (unbeknownst to one another) on the far side of the moon. Of course, one group is from the US and the other is from the Soviet Union (this story was written in 1957, after all). Having carried out their separate, secretive schemes, neither side can even imagine that the other would do the same. So what happens when the Americans set up camp and start investigating the far side of the moon? They find lunar creatures that look strangely like themselves! The story turns into a real eye-roller when the two groups of astronauts make contact, see one another without their space helmets on, figure out how to communicate, and then exchange information about their own cultures, all the while failing to realize that everyone there is human. Boulle puts too fine a point on this, but remember that this is 1957 and the Cold War is quite toasty. On the moon, separated from their respective nations and enmities, Americans and Soviets are the same–neither one is much more scientifically advanced than the other and they’re interested in learning more about the moon and how they can use it to their own advantage. The optimists among us might think that, once the two groups realize who the other is, they’d hug and make peace and everything would be great. But this is Boulle so of course that doesn’t happen. Rather, both sides agree that the moon must be destroyed. Of course.

“The Perfect Robot” and “The Man Who Hated Machines” explore the sometimes extreme ways in which humans react to intelligent machines. In the first story, a brilliant scientist (Professor Fontaine) who works for the Electronic Brain Company (EBC) is tasked with perfecting “calculating machines,” though he doesn’t stop there. As his research into cybernetics continues, he starts making the case for “thinking machines,” which some on the board of directors dismiss. Nonetheless, Fontaine argues that many things that seem uniquely human are not so different from what machines can do:

properly speaking there was no such thing as ‘creation’, since this word should always be understood in the sense of ‘combination’ or potential rearrangement of former facts. According to [Fontaine], in all operations of the human mind the solution or outcome was always contained, at least implicitly, in previous data. The brain had never done otherwise than modify the disposition of these data and present them in a new aspect. Consequently, between the aforesaid human brain and the artificial electronic brain there was a difference only of quality and not of nature. (81)

So there, board of directors! Remember, though, this is Boulle, so he takes the idea of a “perfect robot” to its limits. Over time, Fontaine figures out (stay with me here) how to make robots solve all mathematical problems, always win at chess, pair up with robots of the opposite sex, and have robot babies (I know, I know). There’s just something…something that still isn’t quite right. Wait…Professor Fontaine’s got it! Robots can become more “perfect” = “human” by…making mistakes!

Unlike some of the stories in this collection, “The Man Who Hated Machines” is more disturbing than humorous. The narrator explains that he first met this particular unnamed machine-hating man when he observed the latter deliberately avoiding a sensor that automatically opened a door to a bookshop. Striking up a conversation, the narrator learns that this machine-hater deliberately sabotages machines so as to satisfy his obsessive and increasingly deranged need to show humanity’s superiority to mechanical devices. Eventually, the machine-hater trains himself to be a walking calculator who can beat a machine…until an even more complex machine is built by a slightly deranged millionaire to beat him. The contest gets so out of hand that by the end, neither man nor machine can even calculate 1+1. Where the story gets disturbing is when Boulle’s narrator describes the hater’s thorough deconstruction of the sophisticated machine, with wires, tubes, buttons, and other pieces scattered around or deliberately inserted into the wrong places. The machine becomes more human, then, and the hater becomes less so.

In “The Diabolical Weapon,” a group of high-level military men gather to report their findings to the prince, an enlightened and intelligent ruler, explaining that atomic weapons have made all other weapons, armies, and maneuvers obsolete. Their ultimate suggestion: ban atomic weapons (not, of course, because they do unbelievable damage and could kill millions but because soldiers and officers need something to do).

We can see the germ of the idea for Desperate Games (1971; tr 1973) in “The Age of Wisdom,” a story about two competing factions of scientists (the worshipers of the particle and the followers of the wave) who think they can “fix nature.” As in “The Lunians,” both factions undertake secret research, not realizing the other is doing the exact same thing. The goal: to balance the temperature around the globe, thus warming the poles and cooling the equator. Apparently neither side thinks through the resulting destruction that this will cause, and since both factions are doing it, well…nothing good comes of it.

And finally, “The Miracle” seems to be where Boulle works out his ideas for The Good Leviathan – specifically, where spirituality and science converge. Here, a priest gives a powerful sermon about the necessity of believing in miracles. One woman, taking the priest’s words to heart, brings her son (whose eyesight was severely damaged in the recent war) to the church and demands that the priest heal him. Realizing that the woman has taken his words literally but unable to refuse her, the priest lays his fingers on the young man’s eyelids and asks God for a miracle. Ironically, a miracle does happen–the young man can see again–but the priest (yes, the priest) refuses to believe it. The young man’s doctor and several prominent eye specialists all examine him and conclude that, truly, the restoration of the man’s eyesight can’t be attributed to anything but a miracle. Word gets to the bishop, and then to Rome, where a thorough investigation is launched into what happened in this small church in France. Even when the Vatican declares that the miracle is real, and the doctors all agree, the priest simply cannot bring himself to believe it. As one of Boulle’s biographers explains, this “story centers around the conflict between science and religion, a conflict that not only has preoccupied both scientists and philosophers for centuries but also constitutes an important theme in Boulle’s work. Despite his own professed lack of belief…, Boulle’s Catholic education is evident in much of his work” (97-8).

Time Out of Mind and Other Stories, then, is an early collection of Boulle’s ideas, which he’ll expand on in his later novels. While some are so absurd they’ll make your eyes roll back into your head, others explore serious issues about cybernetics, space travel, and spirituality that are alive and well in the twenty-first century.

* I’m leaving out of the discussion the non-speculative stories “The Man Who Picked Up Pins” and “The Enigmatic Saint”

February 9, 2022

Review: Planet of the Apes by Pierre Boulle

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

Julliard, 1963

Julliard, 1963

translated by Xan Fielding

Vanguard Press, 1963

246 pages

If you’ve watched the 1968 Planet of the Apes film, that’s great. Now forget all about it.

Pierre Boulle’s novel Planet of the Apes is, like many of the author’s works, a social satire. Presented in the guise of a literal message in a bottle (but floating in space instead of water), Boulle’s text is narrated by journalist Ulysse Mérou who, along with Professor Antelle, the young physician Arthur Levain, and the chimpanzee Hector, embark on a voyage to the Betelgeuse region, three-hundred light-years away. Embarking in the year 2500 and traveling near the “speed of light minus epsilon,” this crew of discovery reaches the planet they nickname Soror in a few years, while three hundred have passed back on Earth. So far, so good.

Upon landing on Soror, the three men quickly realize that the air is breathable and the food digestible. And then they meet some…strange humans. Without clothing or language, the humans of Soror live in the forests, foraging for food and sleeping in groups. When Ulysse and his companions try to interact with them, the humans act frightened and hostile, at first. As Ulysse notes, these men and women lack a certain “spark” of intelligence and seem content with their very basic lifestyle.

The real shock comes when Ulysse, Antelle, and Levain meet the real rulers of the planet: gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans. Dressed in various uniforms and other human clothing, the apes drive cars, live in houses, cook, play sports, and run scientific institutes where humans are the lab rats. Separated from his companions, Ulysse is taken to one of these labs and placed in one of the many cages housing other humans. Desperate to prove his intelligence to the apes studying him, Ulysse learns their language and befriends one of the scientists (Zira). She, in turn, forms a relationship with Ulysse and helps him prove to the scientific leaders that he is not like the other humans, but is from another planet where evolution unfolded differently than on Soror.

During his captivity and over the course of many conversations with Zira, Ulysse learns that the apes of Soror view themselves as the only intelligent species on the planet. Their most important scientific studies center on how they evolved this intelligence while humans did not. Eventually, Ulysse realizes that the technology around him is slightly behind that of the Earth that he left, and another ape scientist confirms that it has been mostly static over the past few hundred years. It’s almost as if apes, which are very good at mimicking humans, were engaged in a very complex mode of imitation…A major archaeological discovery then throws into question ideas about ape evolution and suggests that Soror may have looked a lot like Earth in the distant past.

As a growing number of apes start to worry that Ulysse is inspiring the humans around him to revolt (indeed, he is), a plan materializes to get rid of this bothersome human. Zira and her friends, though, help Ulysse, his female companion (whom he met upon landing on the planet), and their son escape and return to Earth. The homecoming Ulysse receives, though, is not the one he expected…

Boulle uses Planet of the Apes to question humanity’s belief in its own natural superiority. Is human civilization really a given, or is it as fragile as a porcelain figurine? Since we know that apes are able to do many things that humans do, could they, in time, overthrow us and establish their own civilization? Boulle also comments on hierarchies, noting that the chimpanzees, orangutans, and gorillas stopped fighting one another centuries before and focused on pursuing their own talents: the orangutans form the scientific establishment, the gorillas work as hunters and guards, and the chimpanzees are the intelligentsia. In this way, the three groups support one another and rarely tread on one another’s territory.

The apes, Ulysse learns, have the same personality flaws as the humans back on Earth. Orangutans, for example, are the representatives of “official science”:

Pompous, solemn, pedantic, devoid of originality and critical sense, intent on preserving tradition, blind and deaf to all innovation, they form the substratum of every academy. Endowed with a good memory, they learn an enormous amount by heart and from books. Then they themselves write other books, in which they repeat what they have read, thereby earning the respect of their fellow orangutans. (152)

Furthermore, Boulle wonders if on Earth, humans might even be overthrown by intelligent machines, rather than apes:

That perfected machines may one day succeed us is, I remember, an extremely commonplace notion on Earth. It prevails not only among poets and romantics but in all classes of society. Perhaps it is because it is so widespread, that it irritates scientific minds. Perhaps it is also for this very reason that it contains a germ of truth. Only a germ: Machines will always be machines; the most perfected robot, always a robot. But what of living creatures possessing a certain degree of intelligence, like apes? And apes, precisely, are endowed with a keen sense of imitation… (210)

Questions of evolution, civilization, intelligence, and origins punctuate Planet of the Apes and invite present-day readers to continue asking them, lest we let the world we’ve built over the centuries slip between our fingers.

February 3, 2022

Review: The Good Leviathan by Pierre Boulle

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

Julliard, 1977

Julliard, 1977

translated by Margaret Giovanelli

Vanguard Press, 1978

204 pages

Pierre Boulle published The Great Leviathan, the story of a massive, nuclear-powered oil tanker, eight years after the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill, in which over three million gallons of oil were released into the waters off California’s coast. One year later, America held its first Earth Day, which is now celebrated every April around the world.

Boulle’s story about the trials and tribulations of the oil tanker, officially named Gargantua, is the very opposite of what you might assume, given the above paragraph. You might be thinking that, clearly, Boulle wrote about how the wonders of nuclear power and the world’s growing dependence on oil are actually recipes for catastrophe.

This is Pierre Boulle we’re talking about, though, so you’d be completely wrong. Following the massive 1969 oil spill and the 1973 oil crisis, France turned to nuclear energy, imagining a grand plan for supplying most of the country’s electricity through nuclear power. Though France fell short of its goal, it did open many nuclear reactors that still supply most of the power to the nation.

Enter Boulle’s 1977 novel and the ship Gargantua, a nuclear-powered, twelve-hundred-foot long tanker capable of carrying six hundred thousand tons of oil. In the face of this threatening monster, we find the ecologists, fishermen, and regular citizens of France losing their shit. Nonetheless, Madame Bach, a shipwoner’s widow and current president of the company that built Gargantua, follows through on her plans, securing a steadfast captain (Müller), an atomic-physicist-turned-industrial-engineer (Monsier David), a highly capable chief engineer (Guillaume), and a publicist (Monsieur Maurelle) to help her turn a profit. The engineers and publicist employ scientists and lab workers to confirm, multiple times, that the tanker is safe and won’t leak nuclear radiation or oil except in the case of an unlikely disaster. Despite the studies and tests, Gargantua is viewed as a monstrous, radiation-spewing creature from hell (thus it is dubbed “Leviathan”).

The launch of Gargantua brings to a head the brewing fight between ecologists and the shipping company. Led by a woman known only as “the Cripple” and a science professor named Havard, the ecologists’ camp holds a series of protests, which culminate in a dicey situation that greets the ship’s return after it’s first voyage. As Gargantua approaches the port, its sworn enemies surround it in small boats and attempt to board the giant, perhaps with plans to sabotage it. Eager to fight off the protesters but insisting on nonviolent measures, Captain Müller decides to spray the trespassers with water from the bowels of the tanker. He succeeds, but then something bizarre happens. The “Cripple,” who received a blast of water, suddenly straightens up, her entire body transforming into a healthy one, which had been twisted from her years working in a factory. Everyone in the area freezes when they see this, and I think you can guess what happens next.

Gargantua instantly turns into a quasi-religious shrine. People start going on pilgrimages to the ship to sample the “miraculous” water and heal themselves. A man who’s been going blind for years rubs tanker water on his eyes and can suddenly see perfectly well. Captain Müller flies into a rage, denouncing those who talk about the water’s miraculous properties, pointing out that it’s just plain old water. Some suggest that maybe the water’s interaction with the radiation gave it special properties, but Müller reiterates that the water and the propulsion system are completely separate. Madame Bach, along with Monsieurs David and Maurelle, share the captain’s skepticism but, unlike Müller, think about how to take advantage of the fishermen and ecologists’ newfound devotion to the tanker.

Pilgrimages to Gargantua continue while the ship is in port undergoing minor repairs, resulting in a makeshift town. The healthy and the sick all come to be near the seemingly-miraculous water, and now the captain has a new problem. Instead of trying to fight off saboteurs, he must shake off ardent pilgrims, who might get themselves killed trying to sneak onto the tanker. Everyone involved in the enterprise knows that the slightest bad publicity could spell disaster, so extra steps are taken to secure the ship. Eventually, the ship shifts from being just an oil tanker to being both a tanker and, when it’s in port, a source of power for the growing settlement, which Madame Bach subsidizes and turns into a clean, well-developed town.

As with his other speculative novels and stories, Boulle uses a single idea to raise questions about a major polarizing issue of the day; in this case, the clash of modern technology and spiritual belief. Referring multiple times to the real-life French Jesuit priest, scientist, and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who often blended science and Christianity, the physicist Monsieur David imagines an intoxicating comingling of ideas about God and the evolution of the universe. As he notes in a televised interview when discussing whether or not the tanker water produced a “miracle,” “It is a question…of the adoption of the uncertainty principle, which most men of science accept today” (95). Quoting then from Sir Arthur Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World (1928), David explains that “ ‘a serious consequence of the abandonment of the principle of causality is that it leaves us without a clear distinction between the natural and the supernatural.’” Thus as theoretical physics moves away from testable hypotheses, the physical nature of our world becomes, once again, inscrutable. David, though, sees this as the next step in humanity’s understanding of the universe.

Furthermore, as in Desperate Games, Boulle explores human nature when people act en masse. As David and Maurelle explain to their boss, Madame Bach, just a single miraculous occurrence will engender others, simply by the power of suggestion. The world’s wholesale shift from hatred to adoration of Gargantua suggests what many who study crowds have known: that nuance and analysis are lost when a crowd forms. Hope, companionship, and the desire to fit in drive human nature. Even the former avowed enemy of the tanker wanted, deep down, to be powerful and recognized by others for her intelligence. Her crusade against Gargantua, the narrator explains, was just a vehicle for that deeper desire.

Even more interesting is Boulle’s point about the ways in which dangerous obsessions lead to the very disasters that people wish to avoid. Even after the tanker “miracles,” Professor Havard despises Gargantua, and from so many years of warning the world that nuclear power and oil will destroy the Earth and all of its inhabitants, he almost comes to wish that something terrible would happen (even if he has to make it happen himself), just to be able to tell the world he told it so. Boulle silences even Havard when the tanker, rather than taking life, actually saves several thousand lives during a storm by releasing oil into the ocean and calming the violent waves.

Now, you might read this and conclude that The Good Leviathan sounds like the silliest of novels. Nuclear-powered oil tankers saving the world and curing illnesses? I admit that the premise is pretty out there, but I’d also suggest that we see that as Boulle’s point. What, in the 1970s especially, would have caused some pretty intense outrage around the world? That’s right: a radiation-spewing, ocean-polluting tanker built and run by a money-grubbing industrialist that would destroy the environment. Boulle used this issue, which generated both then and now some pretty intense emotions, to reveal the complex motivations and desires that drive people to support or oppose major initiatives. How do we sort ourselves politically, intellectually, and spiritually when it comes to problems that we all face together? How might we react when we join a movement or when we become frustrated with a lack of recognition for our efforts to make the world a better place?

Boulle used questions raised by Gargantua as a vehicle for social commentary and for a deeper understanding of human nature.

February 1, 2022

Out This Month: February

Echo

by Thomas Olde Heuvelt, translated from the Dutch by Moshe Gilula (Tor Nightfire, February 8)

Echo

by Thomas Olde Heuvelt, translated from the Dutch by Moshe Gilula (Tor Nightfire, February 8)

Travel journalist and mountaineer Nick Grevers awakes from a coma to find that his climbing buddy, Augustin, is missing and presumed dead. Nick’s own injuries are as extensive as they are horrifying. His face wrapped in bandages and unable to speak, Nick claims amnesia—but he remembers everything. He remembers how he and Augustin were mysteriously drawn to the Maudit, a remote and scarcely documented peak in the Swiss Alps. He remembers how the slopes of Maudit were eerily quiet, and how, when they entered its valley, they got the ominous sense that they were not alone. He remembers: something was waiting for them…But it isn’t just the memory of the accident that haunts Nick. Something has awakened inside of him, something that endangers the lives of everyone around him…It’s one thing to lose your life. It’s another to lose your soul.

REVIEWS

Rachel Cordasco reviews Desperate Games on SFT

Review: Desperate Games by Pierre Boulle

This is part of a series on French author Pierre Boulle.

translated by Patricia Wolf

Vanguard Press

1973

213 pages

If Desperate Games was a person, it would be that kid at school who always kept to himself and seemed perfectly happy with that, who did his own thing without even seeming to notice that others might find that thing strange, and who wore what he wanted without caring about the latest fashions.

Unlike what many of us readers are used to these days, this is not a book about characters and their desires/motivations. This is a book about an idea, one that, as Michael Orthofer says in his review, could spawn several other books. Boulle’s central question is this: what would happen if the foremost scientists in the world formed a global government to solve humanity’s most pressing problems? Well, according to Lucille Frackman Becker, Boulle’s biographer, the author approaches questions like these with the belief that “however admirable [a] scientific goal may be…the methods used to achieve the goal gradually pervert the original intention and lead to an ill-fated denouement” (Pierre Boulle, 80). She cites The Energy of Despair, Mirrors of the Sun, and The Good Leviathan as others of Boulle’s texts that work through this issue.

As I said, characters are not important to Boulle except as vehicles for working out his ideas, which is reminiscent of the Naturalists of the late-19th and early-20th centuries (Zola, Dreiser, Norris, Cather, Crane, Wharton, etc.). The characters of Desperate Games are like chess pieces in a grand game of human nature, history, and scientific progress. I’m certain that if you can get past the woodenness of the characters (and I confess, it was a bit hard for me), then you can really enjoy this absolutely wild, absurd, bizarre, and terrifying novel of hubris and self-destruction.

It all starts off so well. After viewing the nightly news reports with growing disgust over many years, several scientists from various nations (with physicists, biologists, and psychologists prominent among them) decide to form a world government. Their goal: to solve major problems like famine and disease that, they believe, could easily be fixed with some logical, scientific adjustments. To do this, they exchange top-secret information about weapons and battle-readiness and then release a statement to the world’s major newspapers declaring that now the world doesn’t need separate nations or governments and all the leaders should just resign. And they do. Now, that may seem a bit farfetched, but as Boulle’s narrator points out, these leaders have just been looking for an excuse to give up their power. Their people are restless and unhappy, their burdens have become heavier, and they just don’t want to deal with all of the crap that comes with running a country. So they say “great! See you guys later!” and hand over all power to this small group of scientists. Of course, I was waiting this whole time for Boulle to mention the small but vocal group of people that you know would oppose this reorganization of human society. And he does mention it, but briefly. In the world of DG, the vast majority of the world is happy to try something new.

The scientists’ goals are admirable: after fixing the world’s major problems, they turn to raising the intellectual level of all people. To this end, education is totally free and universal…which seems great, until the leaders realize that people are not flocking to school to learn more about the nature of the universe but to gain a deeper understanding of things like…astrology?! Basically, the stupid humans aren’t interested in grand scientific questions but rather in small areas of interest and even pseudoscience. Well that’s disappointing.

To solve this new problem (yes, pretty soon DG reads like a novelization of whack-a-mole), the scientists start sending out the most captivating speakers in their respective fields to jolt their students awake and into caring more about scientific pursuits. Everyone’s still all “meh.” What is a scientist-leader to do?

Oh, and now astronauts and others who operate sophisticated technology have lost their ability to manually control their airplanes, cars, and other vehicles. The onboard computers are so precise that the humans subconsciously give up on trying to make any decisions for the machines. Chaos ensues. Furthermore, the suicide rate around the world has skyrocketed. As in, if nothing is done, the human race will cease to exist. After all, when all of the major problems of the world are solved, technology is streamlined, education is universal, and everything is generally awesome, what’s the point of doing anything?

And let’s not forget that, through all of this craziness, infighting in the government never ceases. Physicists hate the biologists, who loathe the chemists, and all of them hate the literary types, who had to scream and whine until they were allowed to participate in the government at all.

Never one to give up on a problem, Fawell (the leader of the Scientific World Government) turns to the planet’s preeminent psychologist, Betty Han. Always cooler than a cucumber and so logical that one wonders sometimes if she’s actually an android, Han starts coming up with ideas that are so spectacular, they solve the above problems beautifully. Problem is…they’re really destructive. Thanks, cold cold scientific logic.

Enter the eponymous “games.” So Jeopardy or Wheel of Fortune, right? Nope. Think gladiators and lots of blood. Han throws the entire human race back into ancient times when people fought to the death in ampitheaters and audiences cheered them on. Basically, today’s reality tv is tame compared to what Han cooks up. After a while, these “wrestling” championships (which include daggers- how is that wrestling?) get old and the suicide rate, after having plummeted, starts rising again. Han comes up with jousting tournaments, underwater fighting, anything she can think of to rouse the public from its torpor. Nothing works until a mathematician and an astronomer in the government hit on the answer: reenactments of major historical conflicts. And yes, they will be fought with real people, real weapons, real everything. So as not to kill the audiences (thanks, scientists!), these reenactments are filmed and broadcast to theaters around the world with such sophisticated audio/visual technology that Boulle is one step away from VR.

Things get really interesting when the government launches “The Landing,” which replays the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II. Participants can improve on the weapons of the time but can’t, for instance, use 21st century technology in reenacting that mid-20th century war. One side is led by the physicists, and the other is led by the biologists. Remember that they hate each other? The battle gets very ugly very fast. And then the biologists’ side takes it to a whole new level. And then physicists…well, I won’t give away the ending, because Boulle doesn’t take a breath until the very last page.

Like the narrators of Naturalist novels, Boulle’s maintains a strict distance from the events he describes. Very little commentary comes through, even at the most outrageous points. Rather, he lets the characters condemn themselves, since he believes in the reader’s ability to grasp the terrifying irony of the story. As the bloodshed and insanity escalate, the narrative voice stays calm, taking things to (what Boulle believes is) their logical conclusion.

Desperate Games, then, is an experience. It’s unique, horrifying, and unfortunately, doesn’t seem that far-fetched if you accept some of the not-so-believable premises. Ultimately, it’s a fascinating look at the state of the world just a few decades after World War II and a few years after the threat of nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union.

January 29, 2022

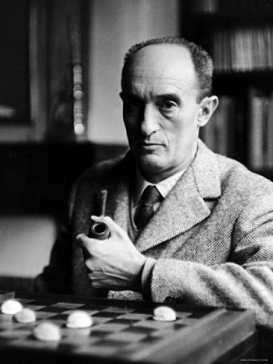

Pierre Boulle

Pierre Boulle (1912-1994) was a French author who wrote several science fiction novels, including Planet of the Apes. Trained as an electrical engineer, Boulle spent eight years in Malaysia as a planter and soldier. His experience as a secret agent with the Free French in Singapore during World War II inspired his famous novel The Bridge on the River Kwai.

Listed below are Boulle’s speculative texts:

Planet of the Apes (La planete des singes), 1963

translated by Xan Fielding (Vanguard Press, 1963)

“In this simian world, civilization is turned upside down: apes are men and men are apes; apes rule and men run wild; apes think, speak, produce, wear clothes, and men are speechless, naked, exhibited at fairs, used for biological research. On the planet of the apes, man, having reached to apotheosis of his genius, has become inert. To this planet come a journalist and a scientist. The scientist is put into a zoo, the journalist into a laboratory. Only the journalist retains the spiritual strength and creative intelligence to try to save himself, to fight the appalling scourge, to remain a man.”

Time Out of Mind and Other Stories (Contes de l’absurde suivis de E=mc²), 1963

translated by Xan Fielding and Elisabeth Abbott (Vanguard Press, 1966)

“Time Out of Mind” (tr. of Une nuit interminable 1953)

“The Man Who Picked Up Pins” (tr. of L’homme qui ramassait les épingles 1965)

“The Miracle” (tr. of Le miracle 1957)

“The Perfect Robot” (tr. of Le parfait robot 1953)

“The Enigmatic Saint” (tr. of Le saint énigmatique 1965)

“The Lunians” (tr. of Les Luniens 1957)

“The Diabolical Weapon” (tr. of L’arme diabolique 1965)

“The Age of Wisdom” (tr. of Le règne des sages 1953)

“The Man Who Hated Machines” (tr. of L’homme qui haïssait les machines 1965)

“Love and Gravity” (tr. of L’amour et la pesanteur 1957)

“The Hallucination” (tr. of L’hallucination 1953)

“E=mc²” (tr. of E=mc² ou le roman d’une idée 1957)

Garden on the Moon (Le jardin de Kanashima), 1964

translated by Xan Fielding (Vanguard Press, 1965)

“Hitler is dead. The German scientists have joined the victors. What started as inspired collaboration at Peenemunde turns into a fatal race as the brilliant ‘lunatics’ scatter across the earth to join up with the big powers in the desperate race to put the first man on the moon. Convention, morality and genius crumble when an inspired contender engineers the world’s greatest upset.”

Because it is Absurd (on Earth as in Heaven) (Quia absurdum: sur la Terre comme au Ciel), 1966

Because it is Absurd (on Earth as in Heaven) (Quia absurdum: sur la Terre comme au Ciel), 1966

translated by Elisabeth Abbott (Vanguard Press, 1971)

“His Last Battle” (tr. of Son dernier combat 1970)

“The Plumber” (tr. of Le plombier 1970)

“Interferences” (tr. of Interférences 1970)

“The Duck Blind” (tr. of L’affût au canard 1970)

“When the Serpent Failed” (tr. of Quand le serpent échoua 1970)

“The Holy Places” (tr. of Les lieux saints 1970)

“The Heart and the Galaxy” (tr. of Le cœur et la galaxie 1970)

Desperate Games (Les jeux de l’esprit), 1971

Desperate Games (Les jeux de l’esprit), 1971

translated by Patricia Wolf (Vanguard Press, 1973)

“Despairing at the state of world degeneration, a group of the world’s most renowned intellectuals form the new Scientific World Government, aiming to put the world to rights. Elected into power, they quickly start making changes for the better, eliminating world hunger and cancer, encouraging scientific thought, and banning frivolous entertainment. But while congratulating themselves on a job well done, they fail to notice that actually, people are not happy. The suicide rate has sky-rocketed and, strangely, it turns out the public wants a little risk and conflict in their lives. So to cater to the masses, the Department of Psychology forms a plan: they will stage an entertainment show the likes of which the world has never seen before. It starts with gladiatorial style battles, bloodthirsty and brutal, where the victors become celebrities of unseen proportions, and quickly escalates into entire historical battle re-enactments involving chemical warfare and mass destruction. The Scientific World Government has unleashed a monster.”

The Marvelous Palace and Other Stories (Histoires perfides), 1976

The Marvelous Palace and Other Stories (Histoires perfides), 1976

translated by Margaret Giovanelli (Vanguard Press, 1977)

“The Royal Pardon” (tr. of La grâce royale 1976)

“The Marvelous Palace” (tr. of Le palais merveilleux de la petite ville 1976)

“The Laws” (trans. of Les lois 1976)

“The Limits of Endurance” (trans. of Les limites de l’endurance 1976)

“Compassion Service” (tr. of Service compassion 1976)

“The Angelic Monsieur Edyh” (tr. of L’angélique monsieur Edyh 1976)

The Good Leviathan (Le bon Léviathan), 1977

The Good Leviathan (Le bon Léviathan), 1977

translated by Margaret Giovanelli (Vanguard Press, 1979)

“A monster sails the seas, carrying the threat of atomic catastrophe on the one hand and of a potential oil slick in the other. This is how a group of worried ecologists perceives the nuclear powered giant oil tanker Gargantua, which they soon nickname Leviathan. But in the end,this evil creature comes out to be a double blessing : first because of the unexpected virtues of atomic desintagretion, and secondly because of the unpredictable carateristic of the slimy poison it holds in its side.”

The Whale of the Victoria Cross (La baleine des Malouines), 1983

The Whale of the Victoria Cross (La baleine des Malouines), 1983

translated by Patricia Wolf (Vanguard Press, 1983)

Trouble in Paradise (Les coulisses du ciel), 1979

Trouble in Paradise (Les coulisses du ciel), 1979

translated by Patricia Wolf (Vanguard Press, 1985)

Mirrors of the Sun (Miroitements), 1982

Mirrors of the Sun (Miroitements), 1982

translated by Patricia Wolf (Vanguard Press, 1986)

“After Jean Blondeau, a pro-environmentalist, becomes President of France, he begins a project that will give his country’s entire population all of its necessary energy and eradicate pollution, but the venture soon becomes a nightmare.”

Review: I am the Tiger by John Ajvide Lindqvist

I reviewed Swedish author John Ajvide Lindqvist’s novel I am the Tiger, translated by Marlaine Delargy, for Strange Horizons.

Here’s an excerpt from the review:

Perhaps that’s because John Ajvide Lindqvist was a magician before he was a writer, a line of work he details in I Always Find You, the book that precedes I Am the Tiger in the Platserna (Places) trilogy. Lindqvist doesn’t want readers to pay attention to how the story is told, only what is happening within it. This opacity functions well on both that level and on the level of plot, where a vaguely supernatural creature seems to be driving a massive increase in drug dealing in the Swedish suburbs. Lindqvist, like the skilled magician he is, focuses our attention on the two troubled protagonists while distracting us from the destruction to come.

Read the entire review here.

January 24, 2022

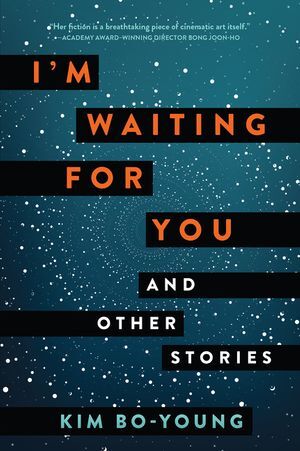

Guest Review: I’m Waiting For You and Other Stories by Kim Bo-Young

Kalin Stacey is a writer, educator, and activist based in Toronto, Canada. He is currently a student of translation studies at Glendon College, a voracious reader of SFF, and an aspiring translator of speculative fiction.

translated from the Korean by Sophie Bowman & Sung Ryu

translated from the Korean by Sophie Bowman & Sung Ryu

April 6, 2021

336 pages

grab a copy here or from your local independent bookstore or library

Occasionally translators find themselves in a position to offer Anglophone readers treasures we otherwise wouldn’t be able to discover—and I’m Waiting for You and Other Stories, by South Korean author Kim Bo-Young, is truly a treasure. Although Kim is by all accounts a leading voice in the SFF community of her home country, this book is only the first full-length collection to appear in English, appearing as it did last spring (and followed very soon afterwards by On the Origin of Species and Other Stories in May 2021).

I’m Waiting for You presents two pairs of linked stories as well as several afterword pieces by various parties involved in their development: the author, the translators, and the two original recipients of the first story. As it happens, the eponymous novelette “I’m Waiting for You” has a fascinating origin story; it was commissioned by a fan of Kim’s so he could recite it to his girlfriend as a sort of bespoke, personalized marriage proposal. Although it was originally intended to be a private story for that one couple, they later agreed to share it with the world, and each wrote letters, included at the end of the collection, about the story’s meaning for them.

And the story itself is beautiful. Taking the form of a space-faring epistolary romance, the narrator writes a series of letters to his betrothed from his relativistic-speed space travel on the “Orbit of Waiting.” This journey, which starts out with the intention to wait for his lover until she returns from a lengthy interstellar trip, soon becomes more complicated as one of them encounters an obstacle, leading to a domino effect of delays that span years, decades, centuries. At first filled with quirky humour, ”I’m Waiting for You” becomes darker and lonelier as it progresses and as the protagonist skips forward in time in attempt to recover the hope of returning home and fulfilling his engagement. But with so much time passing, it may just be that the married life he imagined will be harder to realize than he ever thought possible. Since I don’t want to spoil the evolution of the story for future readers, I’ll leave it there. Still, Kim is able to weave a remarkable narrative—at times touching, at times unsettling—in such a short space.

It is followed by the mind-melting, novella-length story “The Prophet of Corruption,” which could perhaps be described as metaphysical science fiction, although such a description does not do it justice. It follows the Prophet Naban, oldest among a cohort of primordial beings who make up the very fabric of the universe and reside in the Dark Realm. They routinely reincarnate into living beings in the Lower Realm (our world) so as to grow and learn from the experiences of each new life. And while they are able to separate and “birth” new entities (think of cell reproduction, as an analogy), they retain an acute understanding of the Oneness of all reality, the sentience of every thing, and the illusive nature of life itself. Until, at any rate, a growing, insidious corruption spurred on by the Prophet Aman threatens to destabilize this Oneness, and with it all existence.

While “The Prophet” clearly draws heavily from aspects of Buddhist cosmology, it also incorporates elements of other mythological figures, in particular from Asian cultures. Despite the heavy emphasis on cosmology and mythology, it still incorporates aspects of science and science fiction, and contrasts the powers of divinity with the powers of science (in fact, any review would be remiss not to at least mention one of the story’s greatest characters: the troubled, im/permeable wall of a spaceship — but you’ll have to read it to understand why). “The Prophet” explores the nature of reality, the history of the universe, and the immutable tension between individuality and the collective whole. It is dense and challenging, a unique contribution to speculative fiction and, quite frankly, a masterpiece.

The third story, “That One Life,” is essentially a sequel to “The Prophet,” and it is much shorter and less developed. It depicts three potential – maybe even parallel? – lives of the Prophet Naban at the end of the universe. It’s very open-ended and leaves room for lots of interpretation, and as a conclusion, it doesn’t quite live up to what came before. Nevertheless, it shows Kim’s definitive ability to shift perspective and freshly explore her established worlds.

And that very approach is how she finishes the volume: with “On My Way to You,” an epistolary answer of similar structure to the first story, this time written by the fiancée of the first narrator. It chronicles her journey across space and time as she tries, beset by very different hardships, to reunite with him.

Beyond the excellent stories, one of the special aspects of this book is how front-and-center the author’s reflections and the translators’ presence are. Among the afterword pieces previously mentioned, there are letters exchanged between the two translators reflecting on their work and collaboration. It is wonderful to see translators afforded this kind of space, as it is often so lacking in the world of literary publishing. The result is a book where the title’s promise of “other stories” moves beyond fiction and includes layers of non-fictional stories about love, courtship, unusual writing project, and the art of translation.

One can only hope that I’m Waiting for You and Other Stories marks the beginning of increased attention to (and publication of) Kim Bo-Young’s work in English, and that the very capable Sophie Bowman and Sung Ryu find their way to sharing more Korean speculative fiction with us.