Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 12

January 4, 2023

Italian SFT in Locus

L ocus Magazine has published my essay on Italian SF in translation over the past five years – check it out here!

December 15, 2022

Review: Freezing Down by Anders Bodelsen

translated from the Danish by Joan Tate

translated from the Danish by Joan Tate

original edition: 1969

translated edition: Doubleday, 1971

183 pages

grab a copy through your local independent bookstore or library

also see SF Ruminations and The Complete Review for their thoughts on this strange and fascinating novel

Anders Bodelsen’s Freezing Down came out in Denmark around the time that Pierre Boulle was publishing science fiction in France (the late 1960s and 1970s). Also like Boulle, Bodelsen was quickly translated into English. And in keeping with Boulle’s wacky and highly entertaining Desperate Games (1971, tr. 1973), Freezing Down features a world sliding into ruin in large part thanks to the scientists who have assumed political power across the globe in an effort to establish a utopia.

Highly focalized through the protagonist (Bruno, a single, young magazine fiction editor), Freezing Down images the results of what later generations would call “cryonics.” When Bruno is told by a doctor in 1973 that he has terminal cancer, he is given the choice of traditional treatment or “freezing down” until some time in the future when his cancer can be cured and he can be brought back to life. Notably, the more isolated Bruno is forced to become throughout the novel, the more this bachelor-by-choice fights against it. Before undergoing the freezing process, Bruno has one last fling with a ballerina (Jenny), whom he met at a recent party. This night with Jenny results in a son, whom Bruno meets when he is thawed in 1995.

From the moment Bruno wakes up in 1995, he realizes just how alien the world has become (see Hal Bragg returning to Earth and finding it an alien world in Stanislaw Lem’s Return from the Stars, 1961, tr. 1980). Now people can choose to live solely for pleasure and then die once their first organ gives out, upon which their other organs are divided among ill patients. Others (mostly wealthy professionals) can choose to periodically be frozen and thawed, as well as fitted with synthetic organs, in order to live, effectively, forever. This world run by scientists manipulating organ distribution calls to mind the dystopian world of Gheorghe Păun’s “Prosthesosaurs” (1983, tr. 1995). A more recent example is Swedish author Ninni Holmqvist’s The Unit (2006, tr. 2009).

Frozen down once more because of his depression about his condition, Bruno is then reawakened in 2022, where life is even more dystopian. Growing depressed and desperate as he is kept mostly isolated, given shapeless food, and denied modern magazines, books, and music, Bruno tries to escape what he realizes is a cruel captivity where existence is prized over everything else. The reader is only able to perceive the world through Bruno’s eyes, resulting in an anxiety-filled experience like that felt when reading Kafka. Freezing Down is a unique glimpse into Danish science fiction during a time when translations were bringing more stories to more readers around the globe. So who wants to read more Danish SFT? I certainly do!

December 3, 2022

Out This Month: December

“Upstart” by Lu Ban, translated from the Chinese by Blake Stone-Banks (Clarkesworld, December 1).

“The Cat” by Morana Violeta, translated from the Portuguese by Clara Madrigano (The Dark, December 1).

REVIEWS

November 6, 2022

Out This Month: November

“The Words” by Clelia Farris, translated from the Italian by Rachel Cordasco (Apex Magazine, November 1) (available online 11/15)

“Hummingbird, Resting on Honeysuckles” by Yang Wanqing, translated from the Chinese by Jay Zhang (Clarkesworld Magazine, November 1)

ANTHOLOGIES

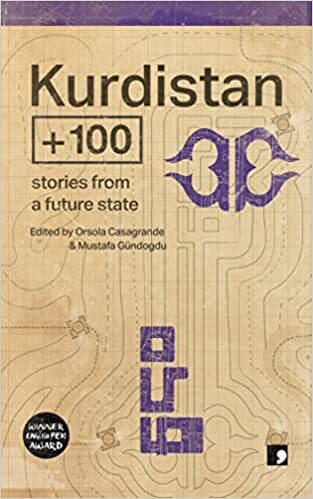

Kurdistan + 100: Stories from a Future State, edited by Orsola Casagrande & Mustafa Gundogdu (Comma Press, November 17).

Kurdistan + 100: Stories from a Future State, edited by Orsola Casagrande & Mustafa Gundogdu (Comma Press, November 17).

Winner of a PEN Translates Award 2021

Kurdistan + 100 poses a question to twelve contemporary Kurdish writers: might the Kurds have a country to call their own by the year 2046 – exactly a century after the last glimmer of independence (the short-lived Kurdish Republic of Mahabad). Or might the struggle for independence have taken new turns and new forms?

REVIEWS

Daniel Haeusser reviews At the Edge of the Woods in World Literature Today

Kevin Canfield reviews Three Streets in World Literature Today

October 1, 2022

Out This Month: October

“Fly Free” by Alan Kubatiev, translated from the Russian by Alex Shvartsman (Clarkesworld, October 1).

“Giant Fish” by Chu Shifan, translated from the Chinese by Stella Jiayue Zhu (Clarkesworld, October 1).

COLLECTIONS

Seven Empty Houses

by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell (Riverhead Books, October 18).

Seven Empty Houses

by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell (Riverhead Books, October 18).

The seven houses in these seven stories are empty. Some are devoid of love or life or furniture, of people or the truth or of memories. But in Samanta Schweblin’s tense, visionary tales, something always creeps back in: a ghost, a fight, trespassers, a list of things to do before you die, a child’s first encounter with a dark choice or the fallibility of parents. This was the collection that established Samanta Schweblin at the forefront of a new generation of Latin American writers. And now in English it will push her cult status to new heights. Seven Empty Houses is an entrypoint into a fiercely original mind, and a slingshot into Schweblin’s destablizing, exhilarating literary world.

ANTHOLOGIES

The

Best of World SF 2

, edited by Lavie Tidhar (Head of Zeus, October 13)

Best of World SF 2

, edited by Lavie Tidhar (Head of Zeus, October 13)

Twenty-nine new short stories representing the state of the art in international science fiction.

Navigating around the globe, The Best of World SF Volume 2 features writers from Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, China, Czech Republic, Greece, Grenada, India, Iraq, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, The Philippines, Poland, Russia, Singapore, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

REVIEWS

September 24, 2022

Review: The Employees by Olga Ravn

translated by Martin Aitken

Lolli Editions (2020), New Directions (2022)

133 pages

grab a copy here or or through your local independent bookstore or library

Olga Ravn’s The Employees is the first work of Danish SFT I’ve ever read, and it doesn’t disappoint. Presented as a series of statements given to a committee by human and humanoid employees, the novel offers a tantalizingly fragmented glimpse of life aboard the Six Thousand Ship.

When the ship lands on a planet they call “New Discovery,” the employees find a group of bizarre objects, which they promptly bring on board. Soon, both the humans and the humanoids begin to feel a strange connection to those objects, with some holding and kissing them, and others imagining that they’ve always known these multi-colored fragments…

There’s something familiar about them, even if you’ve never seen them before. As if they came from our dreams, or some distant past we carry deep inside us, like a recollection without language. (Statement 040)

Developing alongside (or perhaps because of ?) the employees’ growing connections to these objects is an emerging sense of self on the part of the humanoids. Over the course of these statements, the humanoids talk about what it means, to them, to be human and how the human crewmembers treat them. Discussions of death and uploaded humanoid consciousness adds another dimension to these reports. A gradual chill in the relationships between members of the two groups breeds suspicion and threatens to jeopardize the mission.

Running like a thread through all of these recollections, philosophical musings, angry rants, and dreamy fantasies is the strange pull that the alien objects have on everyone living on the ship. It’s like the Strugatskys’ Roadside Picnic, only in The Employees, the objects were deliberately brought on board the Earth ship for study.

Martin Aitken’s translation from the Dutch skillfully captures the emotions always threatening to break through the staid, emotionless genre of the employee report. Hopefully we will see more Ravn in English, especially since we hadn’t had any long-form Danish SFT since 2011 (The Brummstein by Peter Adolphsen) or short-form since 2018 (“The Amputated Arms” by Vilhelm Bergsoe).

So go read The Employees and tell me what you think about it in the comments!

September 3, 2022

Out This Month: September

Swedish Cults by Anders Fager, translated from the Swedish by Henning Koch and Ian Lemke (Valancourt Books, September 6)

Swedish Cults by Anders Fager, translated from the Swedish by Henning Koch and Ian Lemke (Valancourt Books, September 6)

Forget everything you think you know about Sweden. In Anders Fager’s stories, Sweden is revealed as a place where dark and unimaginable things happen. Where deep in the woods bloody sacrifices are made to ancient and monstrous deities. Where two young people’s road trip to visit their grandmother takes a turn for the bizarre and nightmarish. Where a woman’s comfortable middle-class life is suddenly upended when her boyfriend develops a mysterious illness that leaves him with a constant erection and speaking in strange tongues. Where an avant garde artist discovers the veil that separates Stockholm from the shadowy city of Carcosa.

REVIEWS

Rachel Cordasco reviews Shimon Adaf’s Lost Detective trilogy in World Literature Today

Ellis Shuman reviews Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter in World Literature Today

August 1, 2022

Out This Month: August

3 Streets

by Yoko Tawada, translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions, August 16)

3 Streets

by Yoko Tawada, translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions, August 16)

The always astonishing Yoko Tawada here takes a walk on the supernatural side of the street. In “Kollwitzstrasse,” as the narrator muses on former East Berlin’s new bourgeois health food stores, so popular with wealthy young people, a ghost boy begs her to buy him the old-fashioned sweets he craves. She worries that sugar’s still sugar—but why lecture him, since he’s already dead? Then white feathers fall from her head and she seems to be turning into a crane … Pure white kittens and a great Russian poet haunt “Majakowskiring”: the narrator who reveres Mayakovsky’s work is delighted to meet his ghost. And finally, in “Pushkin Allee,” a huge Soviet-era memorial of soldiers comes to life—and, “for a scene of carnage everything was awfully well-ordered.” Each of these stories opens up into new dimensions the work of this magisterial writer.

Beyond

by Horacio Quiroga, translated from the Spanish (Uruguay) by Elisa Taber (Sublunary Editions, August 16)

Beyond

by Horacio Quiroga, translated from the Spanish (Uruguay) by Elisa Taber (Sublunary Editions, August 16)

As he neared the end of his troubled life, Horacio Quiroga penned a collection of stories that straddle thresholds, the ones between life and death, between sanity and madness, between man and nature. Partly set in the labyrinthine Misiones Jungle and haunted by the suicides of his stepfather, wife, and both his children, the otherworldly grace and human tenderness of these stories juxtapose a violently direct prose. Translated for the first time into English, Beyond (El más allá, 1935) brings readers tantalizingly near to the abysses that lurk just on the other side of everyday experience. Includes: “Beyond”, “The Vampire”, “The Flies”, “The Express Train Conductor”, “The Call”, “The Son”, “His Absence”, “Beauty and the Beast”, “Lady Lioness”, “The Puritan”, and “Sunset”.

NOVELS

One Mile and Two Days Before Sunset (The Lost Detective Trilogy Vol.1) by Shimon Adaf, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Picador, August 2)

One Mile and Two Days Before Sunset (The Lost Detective Trilogy Vol.1) by Shimon Adaf, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Picador, August 2)

Who murdered the celebrated rock singer Dalia Shushan? Did controversial philosophy professor Yehuda Menuhin commit suicide or was he murdered? And what is the connection between the two events? These are the questions facing private investigator Elish Ben-Zaken, a former philosophy student, rock music expert and author.

[image error]A Detective’s Complaint (The Lost Detective Trilogy Vol.2) by Shimon Adaf, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Picador, August 2)

Elish Ben Zaken, Shimon Adaf’s enigmatic hero, has given up working as a private detective and makes his living writing detective novels based on unsolved cases from the past. He appears to live an ordinary, balanced life. But person like Elish can’t get away from his past so easily, especially when his niece Tahel calls on him for help. Tahel, a small child in Adaf’s previous novel, is now a teenager and an apprentice sleuth herself. And she has found a mystery to solve: a young woman gets on a bus in Beersheva on a Thursday evening and gets off in Sderot, close to the Gaza border, on Sunday evening. A bus drive that should have lasted an hour has lasted three days. The young woman remembers nothing – as far as she is concerned, the trip took an hour. In order to help Tahel solve this mystery, Elish moves to Sderot. It is the summer of 2014, and Sderot is at the center of the Israel-Gaza war, filled with fear and hate. For Elish, this is a chance to investigate other issues – the meaning of family and the basic human need to look for mysteries and solve them.

Take Up and Read (The Lost Detective Trilogy Vol.3) by Shimon Adaf, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Picador, August 2)

Take Up and Read (The Lost Detective Trilogy Vol.3) by Shimon Adaf, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Picador, August 2)

During his investigation into the disappearance of a girl from Sderot in the summer of 2014, an investigation recounted in the previous book in the trilogy, Elish Ben-Zaken meets poet Nahum Farkash. The encounter was brief and at the time did not carry much weight. But, it is in that brief encounter that Elish may have missed the most important clue for his investigation. Fourteen years later, in an Israel that has gone through great changes, the failure of that investigation and its missing pieces continues to haunt the lives of Elish’s niece and nephew, Tahel and Oshri. The story of Nahum Farkash opens this book and the relations between his unexpected character and the events told in the previous books are gradually revealed. Elish, a character that was an enigma from the very first book, becomes the center of the mystery in this closing chapter.

The Famous Magician

by César Aira, t

ranslated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews (New Directions, August 16)

The Famous Magician

by César Aira, t

ranslated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews (New Directions, August 16)

A certain writer (“past sixty, enjoying ‘a certain renown’”) strolls through the old book market in a Buenos Aires park: “My Sunday walk through the market, repeated over so many years, was part of my general fantasizing about books.” Unfortunately, he is suffering from writer’s block. However, that proves to be the least of our hero’s problems. In the market, he fails to avoid the insufferable boor Ovando—“a complete loser” but a “man supremely full of himself: Conceit was never less justified.” And yet, is Ovando a master magician? Can he turn sugar cubes into pure gold? And can our protagonist decline the offer Ovando proposes granting him absolute power if the writer never in his life reads another book? And is his publisher also a great magician? And the writer’s wife?

REVIEWS

July 28, 2022

Farris in The Best of World SF 2

I’m so excited that Clelia Farris’s fascinating story “The Substance of Ideas” (in my translation from the Italian) will appear in Lavie Tidhar’s upcoming anthology The Best of World SF, Volume 2! And check out that rockin’ table of contents!

July 26, 2022

The Moonday Letters by Emmi Itäranta

Daniel Haeusser reviews short works of SFT that appear both online and in print. He is an Assistant Professor in the Biology Department at Canisius College, where he teaches microbiology and leads student research projects with bacteria and bacteriophage. He’s also an associate blogger with the American Society for Microbiology’s popular Small Things Considered. Daniel reads broadly in English and French, and his book reviews can be found at Reading1000Lives or Skiffy & Fanty. You can also connect with him on Goodreads or Twitter.

translated by the author

translated by the author

Titan Books, July 2022

9781803360447

Earth-born healer Lumi Salo departs Europa after treating a client for the childhood home of her spouse Sol, where she’ll be able to reunite with them. With joyous anticipation of feeling their embrace again soon, Lumi continues to write Sol letters in the meantime, an exercise that makes her feel closer to them.

Sol’s mother and sister greet Lumi at their Martian home, but she is disappointed to find Sol has not yet arrived. The next morning, she receives only a short message of apology from her spouse. They won’t be able to make it, something important has come up with their work that they have to deal with immediately. But they should be able to meet up with her soon.

Lumi has only been granted the privilege of emigrating from humanity’s damaged, impoverished, and pockmarked home planet for the upper-class societies of the moon, Mars, and related fabricated habitats because of her training as a healer. Trained in the mystical healing art by her mentor Vivian, guided through otherworldly realms by her Iberian lynx spirit animal, Lumi traveled throughout the colonized solar system, finding and falling in love with Sol on Mars in the process.

A scientist specializing in astrobotany, Sol has worked on teams adapting plants to human colonies and in research seeking to use photosynthetic species to repair the Anthropocene’s damage to Earth. Whereas many loathe to put any political, economic, or social efforts into the welfare of Earth and its inhabitants, Sol feels an ethical responsibility on the unfortunate left behind in humanities journey into space.

As a healer, Lumi knows little about the details of Sol’s research. And as a scientist, Sol can’t really comprehend the magic that Lumi claims to experience. Coming from literally separate worlds, they are united by their love, and passions to use their skills for the betterment of others.

With each passing day without Sol’s return, Lumi’s worry grows. Whether waiting patiently in place for them, traveling to the next proposed location to meet up, or proactively going to seek them out, Sol remains elusive. Their messages to Lumi become less frequent and cryptic. And then Sol goes missing along with several other researchers in the aftermath of what appears to be a terror attack on a Martian research facility, drawing not only Lumi’s concern, but government interest.

Earth wakes and stones will speak, and darkness recedes over waters .

This enigmatic phrase uttered by her spouse during one of their last public interviews, written in a letter to Lumi, and microbe-grown on the walls of sites targeted by bioterrorism, stirs a memory from Lumi’s past. They are words she’s heard from the mouth of her mentor, Vivian. Starting with these clues, Lumi begins a search through the solar system and past memories and records to find her spouse. Through this she learns the full truth of their Project Earth research, its connection to her past, and the future of her home planet.

So, begins The Moonday Letters, a lyrical epistolatory novel of longing and hope. One part science fiction, one part fantasy, and one part mystery, it becomes linked by the strand of romance, the connection between Lumi and Sol even in separation. Composed mostly of Lumi’s letters to Sol, the novel also contains the messages from Sol to Lumi and other miscellaneous document records or transcripts. With a wistful voice, Lumi’s words flow with a poetic precision and empathetic peaceful calm. Yet, murmuring beneath that calm lies a continuous thread of unease, a growing panic that Lumi allows out in short moments, but mostly tries to tamp down through memories of happiness and togetherness. Nonethelss, Lumi never falls into denial or helplessness. She bravely steps forward to where different paths lead her, even to the dangerous edges and unknown territories of the mystical realms she walks as a healer, protected by her lynx.

Relatively early in the novel, Itäranta introduced me to a new vocabulary word: tralatitious. In one sense, the word simply means conventional, as in something passed down through tradition across generations. In another figurative sense, it refers to the transfer, or derivation, of a characteristic from some external source. I feel as though ‘tralatitious’ sums up many of the themes and elements of The Moonday Letters. It applies to the ceremony of Lumi’s healing rites, the meaning for reality drawn from the spiritual. It applies to the knowledge she has learned from Vivian, and to the relationship she has with the lynx, a symbiosis derived from the magic of the universe. It applies to Sol’s research (and how Lumi unknowingly impacted it.) It applies to Sol’s political and social beliefs, his actions. And it applies to the large-scale ecological themes of the novel, with their speculative setting of well-to-do colonies and a battered, vengeful Earth. The condition of the Earth has been passed down as surely as the technology and wealth gained for some through its exploitation.

And that word I put in the last paragraph, symbiosis, is also very central here. Symbiosis is in some ways a tralatitious biological state of existence, a genetic inheritance of relationship through the generations, and a derivation of a singular unit from two separate, external parts. Itäranta doesn’t just put that concept into The Moonday Letters in the metaphorical senses of the life shared by Lumi and Sol, but also in the biologically literal sense of lichen, a ‘species’ that is actually a symbiont of multiple species: fungal (at least two types), algae, and cyanobacterial. Lichen is central to the plot, and it is beautiful how well Itäranta incorporates the themes, characters, and plot of this novel into a glorious symbiotic whole. The Moonday Letters works on so many levels.

The mystery of the novel propels the novel forward, both character action and reader engagement. The only hurdle that I felt necessary to overcome while reading The Moonday Letters was a consequence of its epistolatory nature. Addressing her letters to Sol, Lumi doesn’t just write from a first-person perspective, but also the second-person ‘you’ to explain or recall events to them. In small bits, I can handle this, but there were certain stretches of the novel where I wanted to just skip over drawn out explanation of what ‘you did’. Sol should know what they did. They shouldn’t need Lumi explaining it to them and recalling all the details. This drives me nuts.

Now, after all that, readers here may wonder why this review is being put up on Speculative Fiction in Translation. The Moonday Letters is technically not a translation. Yet, it sort of is. Though published first in Finnish a couple years past, Itäranta wrote the novel concurrently in both Finnish and in English, separately. The two texts then went through unique editing processes. Thus, it’s not quite a translation by the author in the sense that the Finnish text became a template for the English. Instead, they each were composed in temporal alignment, likely feeding off one another, and then further evolved along distinct linguistic paths. Given how important language is to the novel – both in its atmosphere and its precision in words, I wish I were able to read Finnish to compare the two. But, I suspect like a tralatitious translation, The Moonday Letters and Kuunpäivän kirjeet have particular unique characteristics one to another, as well as a shared, symbiotic unity.