Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 10

September 2, 2023

Review: HWJN by Ibraheem Abbas

translated by Yasser Bahjatt

first English edition: 2013, Yatakhayaloon

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Arabic speculative fiction in translation has become more common since 2000, but the number of titles is still unfortunately small. HWJN, then, is an important example of what Arabic SFT has to offer, and it’s thanks to Saudi author Ibraheem Abbas and translator Yasser Bahjatt, who co-founded The League of Arabic Sci-Fiers, that we have HWJN and other similar works.

HWJN introduces us to a new world—the realm of the Jinn. Narrator Hawjan (HWJN) speaks directly to the reader throughout the story, explaining how he fell in love with a human woman and what he ultimately needed to do in order to save her life.

Part guidebook, part confession, HWJN details how humans gradually moved into neighborhoods inhabited by Jinn (invisible to humans) and others who occupy another dimension. Many Jinn chose to move, but Hawjan, his mother, and his grandfather stayed in the house they had lived in for years, even as a human family moved in. Sawsan, their daughter, is a highly-intelligent med school student, and immediately attracts Hawjan’s attention. When her friends start experimenting with a Ouija board, Hawjan takes the opportunity to communicate directly with Sawsan. This initially frightens her (and her friends), but then the two gradually draw close, communicating via a tablet (Hawjan is able to materialize just enough to move Sawsan’s fingers in order to type messages to her).

When Sawsan finds out that she has a brain tumor, Hawjan realizes that she has become a pawn in a much larger feud that involves his own father’s death and powerful devil Jinn. In order to save Sawsan, Hawjan must marry a fellow Jinni and give their son to the leader of these Jinn. Hawjan is helped by Eyad, Sawsan’s human admirer, and together they defeat Hawjan’s enemies and stop Sawsan’s father from falling into their clutches out of his desperation to save his daughter.

Given that this book comes from a culture whose values are sometimes quite different from that of the West, some references and assumptions might be off-putting to Anglophone readers. The subordinate role of women in HWJN, for example, might make some Western readers uncomfortable. Nonetheless, it is precisely by reading books that come from traditions and languages different from our own that we can more fully understand other cultures and the people who form it. Thus HWJN is not just a book but another step on the way to forging ties with people across the globe.

Of course, without translator Yasser Bahjatt, we wouldn’t have HWJN in English at all. And the translation is very good. And yet, as with some works of SFT, the text would have benefitted from a more thorough edit, given the not-insignificant number of spelling and grammatical errors. Despite this, HWJN offers us fascinating glimpse into the world of the Jinn and Arabic culture.

August 12, 2023

Review: Simantov by Asaf Ashery

translated by Marganit Weinberger-Rotman

original publication (in Hebrew): 2020

first English edition: 2020, Angry Robot

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

One of the fascinating things about contemporary Hebrew SFT is that it includes a subset of novels that smash together the detective genre and biblical themes. Books like Ofir Touche Gafla’s The World of the End, Nava Semel’s Isra Isle, Shimon Adaf’s Lost Detective Trilogy, and Asaf Ashery’s Simantov (the subject of today’s review) feature detectives solving crimes against an otherworldly backdrop. Given that Israel is a highly contested place claimed by the world’s three major religions, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that biblical themes find their way into Israeli literature. The detective angle, though, underscores the theme of “revelation,” in the sense of uncovering the truth and understanding what God expects of humans.

Simantov focuses on a more obscure biblical story–that of Lilith, who was created before Eve to be Adam’s partner. Her refusal to follow orders led to her exile from the Garden of Eden; thus Eve’s creation. Since then, a group of women descended from Lilith have established themselves on Earth as a major force in women’s rights around the world. As one of the characters in the novel explains, it is because of these women that all women have been able to enter any field they choose and find success in their work.

These descendants of Lilith, though, suddenly find themselves threatened by another group–the Nephilim. These are giant fallen angels who are trying to open the gates of Heaven. If that were to happen, the world as we know it would end. One by one, a daughter of Lilith is kidnapped by the Nephilim, since their sacrifice will accomplish the angels’ goal. It is up to two detectives–Chief Inspector Yariv Biton and his ex-lover Mazzy Simantov, who runs the Soothsayer Unit of police diviners–to find the women and stop the Nephilim.

Complicating matters is the fact that Mazzy’s mother, Rachel, has strong divining powers and an even stronger personality. Though she and Mazzy are somewhat estranged, Rachel jumps into the investigation, not just to help find the missing women, but also to protect her daughter, whom she knows is in danger, since the Nephilim are powerful and ruthless.

What ensues is a story about a race against time as the various members of the Soothsayer Unit use their powers to figure out how to stop the fallen angels. Eventually, the soothsayers figure out the names of the Nephilim, which is the only way to stop them from opening the gates of Heaven.

Marganit Weinberger-Rotman’s translation is smooth and very readable, but the story itself was lackluster and the characters were somewhat flat. Nonetheless, Ashery’s blending of detective fiction and biblical themes offers readers an interesting perspective on this growing subgenre of Hebrew literature.

August 5, 2023

Out This Month: August

SHORT STORIES

“Who Can Have the Moon” by Congyun ‘Muming’ Gu, translated from the Chinese by Tian Huang (Clarkesworld, August 1).

“Who Can Have the Moon” by Congyun ‘Muming’ Gu, translated from the Chinese by Tian Huang (Clarkesworld, August 1).NOVELS

The Kindness by John Ajvide Lindqvist, translated by ? (riverrun, August 3).

A shipping container is mysteriously dumped in the Swedish port town of Norrtalje. Due to their ignorance of its ownership it isn’t until a week has passed that the authorities can have it forced open. There the remains of twenty eight refugees are found, a situation of unrelenting horror. Not only that; a black sludge pours out which contaminates the river and is the cause of a new, sickening dread that affects Norrtalje’s inhabitants, causing a lack of trust, aggression, violence. It seems like an end to Kindness. Six characters are at the centre of this extraordinary novel, six people in search of love and connection, whose extraordinary qualities will confront the metaphysical illness consuming their town.

Cyberpunk 2077 by Rafal Kosik, translated from the Polish by Stefan Kielbasiewicz (Orbit, August 8).

Written by acclaimed Polish science fiction writer and screenwriter Rafał Kosik, the electrifying novel follows a group of strangers as they discover that the dangers of Night City are all too real.

Fishing for the Little Pike by Juhani Karila, translated from the Finnish by Lola Rogers (Restless Books, August 15).

Winner of the Jarkko Laine Literature Prize

In the utterly original, genre-defying, English-language debut of Finnish author Juhani Karila, a young woman’s annual pilgrimage to her home in Lapland to catch an elusive pike in three days is complicated by a host of mythical creatures, a murder detective hot on her trail, and a deadly curse hanging over her head.

July 25, 2023

Review: The Elementary Particles by Michel Houellebecq

translated by Frank Wynne

original publication (in French): 1998

first English edition: 2000

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

“This book is dedicated to mankind.” Thus ends Michel Houellebecq’s strange novel The Elementary Particles, a story about, among other things, half-brothers, France, molecular biology, sex, and morality. Translated beautifully from the French by Frank Wynne and spanning a century, the book focuses mostly on the sad, lonely lives of Michel and Bruno Djerzinski as they each pursue their passion—in Michel’s case, it’s understanding mutations and sexual reproduction; while for Bruno, it’s satisfying his seemingly unlimited sexual desire. While neither one is able to have a long-term, stable romantic relationship, they do eventually find women who accept them as they are, though that happens when all are much older.

Michel, the younger half-brother, finds that he is unable to experience romantic love, despite being close for many years with a girl who lives in his village. Annabelle waits for Michel to express affection, but when he doesn’t, they drift apart, with Michel embarking on a career in molecular biology. His success in academia is paired with a lonely existence, in which he doesn’t feel much of anything, except lingering affection for the grandmother who raised him. As a biographer writes of him many years after Michel’s disappearance/death, “one of the marks of Djerzinki’s genius… was his ability to go beyond his first intuition that sexual reproduction was, in itself, a source of deleterious mutations…[he] understood it was necessary to look past the framework of sexual reproduction to study the general topological conditions of cell division” (136).

This scientific, detached study of sex is reflected in Bruno’s experiences with women, in which sex is described in a monotonous narrative voice and body parts in great detail. The narrator connects what we see as an almost desperate promiscuity with the general dissolution of morality in Western society starting in the 1970s. Sex has become reduced to an exchange and empty pleasure, with relationships breaking down in the absence of real human connection. It is Michel, ironically, who is able to “solve” this problem when he flees France for Ireland and engages in in-depth research into sexual reproduction. Michel figures out that “any genetic code, however complex, could be noted in a standard, structurally stable form, isolated from disturbances or mutations.” Thus, “every animal species, however highly evolved, could be transformed into a similar species reproduced by cloning, and immortal.”

This is what the narrator calls a “metaphysical mutation”–one of the few that has happened so far in human history. And yet, as the ending of the book explains, human history has nearly ended already (in the 2070s). The narrator is a member of this new species, which doesn’t experience the pain or pleasure that humanity did, but that lives in what humans think is a “paradise” (the narrator doesn’t comment on this). Humans are dying out, having replaced themselves via science and technology. Genetic differences have been erased, everyone lives together peacefully—it makes one think about Huxley’s Brave New World, which the brothers discuss in the middle of the book. As Bruno says, people claim that Huxley’s book is a dystopian nightmare but, according to Bruno, it’s actually what everyone is striving toward. The ending of the book, where the reader realizes that the narrator isn’t, in fact, human, is unsettling. For this reader, fewer pages given to Bruno’s sexual experiences and more given to Michel’s breakthrough would have made the book more interesting and less uneven.

July 17, 2023

Review: The Movement by Petra Hůlová

translated by Alex Zucker

original publication (in Czech): 2019

first English edition: 2021

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Written in the form of a memoir by a guard at a re-education facility, The Movement is a disturbing story of brainwashing, idealism, and fear. Set sometime in the future when the Internet has been shut down and robots are commonplace, Hůlová’s story focuses on what has occurred in the “New World” (Eastern Europe) since a powerful movement for gender equality took the world by storm.

Begun by a woman named Rita who was profoundly disturbed by the ways in which women have been sexualized, both in public and private spaces, the Movement grew from a few radical women bombing plastic surgery clinics in Eastern Europe to a worldwide struggle for complete equality. To achieve this, re-education clinics accept (and sometimes kidnap) men in order to put them through months- or years-long rigorous training in appreciating women for who they are, not what they look like. This is not just a series of courses or community service, though; rather, these men are treated like animals, made to strip naked at a moment’s notice and forced to masturbate to pictures of older women and women with scars, sagging breasts, and other signs of age. The goal is to change how men think when they look at young, curvy women versus older women. Indeed, their final exam requires that they not get an erection while a bunch of young, naked women dance around them. Some of these men’s wives are even encouraged to go to reeducation centers in order to learn that makeup and plastic surgery are wrong.

Vera, the guard whose memoirs we are reading, is a true believer in the Movement and its goals. She dutifully records how her “clients,” who are given initials and numbers, either pass or fail their various tests. We learn about how the Institute where she works (and others like it) employ many women, and some men, to help usher in a utopia in which men are only attracted to women because of their souls and personalities, not looks.

Running throughout the book, though, are references to the Institute’s former role as a meatpacking facility. Meat hooks still hang from the ceiling, parts of the building retain their freezer-like qualities, and the smell of meat and blood clings to the walls. It is against this backdrop that the narrator tells her story while insisting on how humane and civilized the Movement is. Nonetheless, the descriptions of nameless men packed into cots and herded around against their will makes the meatpacking imagery that much more relevant.

We don’t even learn Vera’s name until near the end of the novel, when she travels to see her mother at a retirement home run by the Movement. During this journey, Vera has what seems to be an emotional breakdown, crying uncontrollably on the bus without articulating to herself or us exactly what is bothering her. Here and there throughout her memoirs, though, she mentions caring about particular clients, or regretting that previous relationships ended. While visiting another reeducation center, she is confronted by another female guard who objects to the Movement’s violent tactics. We get the sense that Vera has accepted everything that the Movement offers so as to hold on to the life that she has, rather than questioning anything and being thrown into an uncertain future. Early on, we learn that she once worked for a place called “PornJoy,” painting fake female bodies for men to have sex with.

Disturbing and depressing, The Movement is a powerful commentary on the lengths people are willing to go to change social norms and achieve an ideal. Alex Zucker’s skillful translation brings this fascinating story to life, reading so smoothly one forgets that the novel wasn’t originally written in English. I look forward to more Hůlová novels and Zucker translations in the future.

July 14, 2023

Daniel’s Reviews: The Impersonal Adventure by Marcel Béalu

Daniel Haeusser is a microbiologist and an Associate Professor. He reads broadly in English and French, and his book review blog can be found at Reading1000Lives. He also contributes reviews to Skiffy & Fanty, Fantasy Book Critic, Strange Horizons, and World Literature Today. You can also connect with his reviews and book celebration on Goodreads, Twitter, Bluesky, or Facebook.

Wakefield Press continues their noble service of reintroducing English-speaking readers to neglected international authors through fresh translations and rich contextual presentation. Eighth in their well-received “School of the Strange” series, The Impersonal Adventure by Marcel Béalu represents a tale that could equally find home as part of their “Imagining Architecture” that brings together stories of “fantastical architecture, imaginary urbanism, and hallucinatory dwellings.” Béalu’s novella bears striking resemblance to Rodenbach’s Bruges-la-Morte, a recent entry in that latter series that once served as surreal inspiration for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. I’ll return here for a review of Rodenbach’s novella soon, but shades of the themes that Hitchcock explored from that are equally visible with The Impersonal Adventure.

At various points in his life (1908 – 1993) an antiques dealer, bookseller, poet, novelist, and protégé of Max Jacob, Marcel Béalu tried to avoid being compartmentalized to any particular school of thought and inspiration, but became best known as a contributor to the French fantastique, with dream-like echoes of German romanticism. He originally wrote his novella L’Aventure Impersonnelle in the 1940’s, but not until 1954 did French press Arcanes publish the story, and subsequent publications of textual variations followed. Bookended by his introduction and interpretative afterward, translator MacLennan here presents as faithful a reading as possible, while imparting greater ease of readability for modern American audiences. Originally published in four block sections of text without any line breaks, Béalu considered the work a novella of four poems, providing readers reference points of contents, which MacLennan also provides in this issue. But, MacLennan also adds line breaks to separate sections and allow pause amid the whirlwind reveries through misty streets and the ambiguous mind of the protagonist.

The story begins with defining uncertainty and confusion as the narrator ponders his current state within an island city:

“Having concluded the business that brought me to A… there’s nothing more to keep me in this city, but neither is there any pressing need for me to move on to another. Rare are the moments when we feel ourselves once more at liberty.”

Uncertain how to proceed with this freedom, he opens his aide-mémoire notebook to read a fragmentary text he earlier recorded, which includes a faded, partially legible address and a promise that “you’ll certainly find what you are looking for there.”

A few pages later the unnamed protagonist ponders his state of excursion into the city further, prophetically musing that “…the solitary man is drawn to the unknown… But were he to attain the total freedom of which he dreams, it would soon be transformed into a forest of fear.” So wandering, he comes upon the Hotel Providence (Under New Management), where he registers under the name Fidibus, an alias created on the spot in a flash of inspiration. This is the only name by which the reader ever knows the narrator, an esoteric word for the scraps of paper one uses for lighting a pipe.

But, it’s a fitting name, carrying irony with it that echoes the irony in the hotel’s name and sign as well as the title of the novella itself. Fidibus is not serving to ignite much here, but he does seem like a scrap of a tool to be used without his own proper agency or sense of controlled direction. Also written in his aide-mémoire Fidibus finds the name ‘Ogyges’, which he also later finds written as the name of a shop, and learns from a man is a historical reference:

“Long ago, this entire island belonged to Ogyges, my respected ancestor … You ’ ll certainly find what you are looking for there. ”

The likely classical reference by Béalu’s here with Ogyges (Ὠγύγης) derives from its etymology of meaning primeval or primal, perhaps related to island of Ogygia from The Odyssey, where the nymph Calypso detains Odysseus for seven years. In similar fashion, Fidibus has become ironically detained by his freedom in this island city to navigate its ambiguous roads and residents.

Fidibus remarks on the neighborhood around the hotel:

“…old buildings the color of moss, rust, and coal, surrounded by stagnant water, like an enormous steamer with no masts. A few hideous constructions like those that overhang housing projects emerge from that conglomeration…they harbor an ambiguous air of dilapidation and incompletion.”

Amid these he comes across frequent shops advertising furniture, used goods, and (ambiguously) curios. In contrast to the surrounding buildings these shops all seemed constructed to display vibrant ‘slices of life’ in ‘meticulous detail.’ Yet, Fidibus comprehends its an ersatz life, “‘illusions completed by some mannequins placed here and there” that stand out amid the “dirty, disordered, miserably furnished dwellings” that surround, seemingly equally lifeless.

Even with the stores and residences appearing largely unoccupied, Fidibus doesn’t lack for encounters with citizens. Besides the hotel owner, he soon meets an eclectic cast as strange as the city environment: a ‘professor’ and a mysterious ‘spiritual half-brother’, a ‘sinister’ night watchman, and a mute woman without hair, moving among the mannequins, and awakening desire in Fidibus. With such encounters kept brief and episodic, Fidibus never fully becomes comfortable or assured in his sojourn in this city and its many ambiguities. Rather than serving to forge connections through these human interactions the encounters instead highlight “…the often invisible abyss that separates people yawns open here, unfathomable.”

The surreal muddling of real and unreal manifest both in the city and Fidibus’ mind:

“What I took for hopelessly muddled verbosity was the manifestation of an imperishable willpower, what seemed to me to be sentimental prattle was the expression of a marvelous, unfathomable reality. The reality that carries the name of silence, the reality that includes dreams and their fleeting impressions, and everything imaginable and unimaginable, and the foreseen and the unforeseen, the bubble on the thick water of the pond and the smooth back of the whale at the rugged surface of the oceans, the fear in the eyes of the newborn baby and the serenity on the brow of the dying man: the reality that also includes what no one has yet seen, what everyone repudiates or is unaware of, what’s there, ready to appear in this story, like thunder bursting in the skies above the theater while the beauties of spring are blossoming on the stage.”

Béalu’s novella represents one giant surreal knot of ambiguity for both his protagonist and his readers to attempt unraveling. He makes this knot metaphor explicit before the start of the novella with a quote from a Herman Melville novella, Benito Cereno, which shares with The Impersonal Adventure the themes of tension arising through doubt of perceptions, and the fear inherent in uncertainty, in absolute freedom.

Reading The Impersonal Adventure, I became struck with how similar the experience felt to reading a work by Gene Wolfe. Wolfe, who is also surmised to have been inspired by Melville, often played with the same unreliability of character and setting, carefully constructing surreal knots for readers to unravel and harvest interpretation and meaning.

Like with interpretations of Wolfe’s work, any interpretations of Béalu’s novella will likely vary from reader to reader, and no definitive solution to the puzzle of The Impersonal Adventure likely exists. In his afterward, MacLennan writes on the novella through a Freudian lens of psychology, but readily admits this is not necessarily fully valid or unequivocal. With The Impersonal Adventure, ambiguity will reign well beyond its completion.

July 1, 2023

Out This Month: July

NOVELS

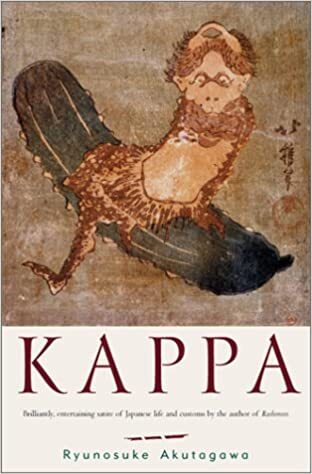

Kappa by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated from the Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell (New Directions, June 6)

The Kappa is a creature from Japanese folklore known for dragging unwary toddlers to their deaths in rivers: a scaly, child-sized creature, looking something like a frog, but with a sharp, pointed beak and an oval-shaped saucer on top of its head, which hardens with age.

Akutagawa’s Kappa is narrated by Patient No. 23, a madman in a lunatic asylum: he recounts how, while out hiking in Kamikochi, he spots a Kappa. He decides to chase it and, like Alice pursuing the White Rabbit, he tumbles down a hole, out of the human world and into the realm of the Kappas. There he is well looked after, in fact almost made a pet of: as a human, he is a novelty. He makes friends and spends his time learning about their world, exploring the seemingly ridiculous ways of the Kappa, but noting many—not always flattering—parallels to Japanese mores regarding morality, legal justice, economics, and sex. Alas, when the patient eventually returns to the human world, he becomes disgusted by humanity and, like Gulliver missing the Houyhnhnms, he begins to pine for his old friends the Kappas, rather as if he has been forced to take leave of Toad of Toad Hall…

The White City Tale by Jeong-Hwa Choi, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (Restless Books, June 6)

Award-winning South Korean author Choi Jeong-Hwa’s English-language debut, The White City Tale is a powerful exploration of existence, social hierarchies, and resilience as one man fights against a system of inequalities in a quarantined city as a pandemic of bodily and mental erasure rages.

June 11, 2023

Daniel’s Reviews: The Lost Village by Camilla Sten

Daniel Haeusser reviews short works of SFT that appear both online and in print. He is an Assistant Professor in the Biology Department at Canisius College, where he teaches microbiology and leads student research projects with bacteria and bacteriophage. He’s also an associate blogger with the American Society for Microbiology’s popular Small Things Considered. Daniel reads broadly in English and French, and his book reviews can be found at Reading1000Lives or Skiffy & Fanty. You can also connect with him on Goodreads or Twitter.

Alice Lindstedt has grown up captivated by the mystery of Silvertjarn, an abandoned mining town whose population of just under 900 people vanished suddenly without a trace in 1959. With no signs of struggle or disaster, the town was discovered eerily pristine, devoid of any human save for the body of woman in the town square, stoned to death, and a sole survivor, a crying newborn tucked away in the school. Over the decades it rested empty, gradually falling to the elements and birthing stories of curses and ghosts from any who have dared enter its limits.

Yet, Silvertjarn exists for Alice as more than a macabre oddity, moret than a source for conspiracy theories and folk tales. Her family has personal history in the village. Alice’s grandmother was born there, but left the tight-knit community for the larger world beyond, her parents and younger sister Aina remaining in Silvertjarn, ultimately to number among the victims of the unknown calamity that befell the population. Letters from Aina through the months leading up to the strage disappearance provide Alice with fragmentary hints of troubles and looming disaster, but Alice has decided the only way to really solve the mystery of this lost village is to go there and search.

As an aspiring documentary filmmaker, Alice assembles a crew to journey to Silvertjarn and spend six days filming in its ruins, exploring answers to the questions of what happened, and what was responsible. Going with her are her friend Tone (who unknowingly also has connections to the mysterious village), her former friend Emmy (an experienced film producer), Emmy’s boyfriend Robert (film technician), and Max (the financial backer for the endeavor.)

In chapters alternating between the events of the past and the present-day exploration of the city, readers discover the truth behind the mystery of Silvertjarn and witness the psychological and physical fractures that can build in a community, whether a population of hundreds, or a small group of film makers.

Both the original title of the novel in Swedish (Staden, literally “The City”) or the title for its English translation by Alexandra Fleming (The Lost Village) highlight the fact that the setting of this novel is foundational to the story, existing almost like a character unto itself. And that setting also represents the greatest strength and success of Sten’s novel. As the plot summary above hopefully conveys, The Lost Village exudes a dark and chilling atmosphere throughout, a mixture of historic Nordic noir and gothic horror. The plot moves forward at a slow creep of dread, but when the action ultimately lets loose Sten releases the horror and terror and gore.

Unfortunately, these successes of The Lost Village are unable to compensate or overcome its flaws. The characters fit into rigid types, showing little growth, and in the case of the modern area, welcome little reader connection or empathy. Now, character growth isn’t necessarily always required, particularly in the realms of genre fiction where emphasis may lie elsewhere. However, the rigid characters here don’t interact in any meaningful way to reveal anything of note or surprising to the reader. They exist as they are, they clash for the point of plot alone, and they predictably fall in relation to one another and their type.

One notable theme that the novel tries to explore through the pair of its female protagonists in both the modern and past age is that of mental illness. While it may be portrayed realistically, the novel novel does not go far enough in bringing that theme of mental illness beyond the cliché, or to really offer any profound insight beyond what any story harboring a character with that trait may do. Again, like with the plot and atmosphere to The Lost Village, great intention and profound opportunity here, but failed execution.

The other major flaw in the novel from my perspective is in its ending and its failure to either embrace the supernatural or straddle the line between conventional and fantasy. I do not consider the choice of offering a 100% conventional explanation for the disappearances of the population of Silvertjarn to be a mistake a priori. It’s not my preferred type of fictional tale, but it’s certainly valid and can be done well. The grave mistake here is that Sten invokes a conventional explanation to the mystery that stretches the imagination and credulity well beyond what a supernatural one would have. Sten seems to want to make a cookie-cutter kind of thriller here, while teasing supernatural horror elements, and giving an obligatory twist that ends up being the literary equivalent of M. Night Shymalan’s worst in film.

The Lost Village is a novel with fantastic inspiration and a strongly atmospheric foundation that loses itself in the choices of its execution, from the development of its characters, and their inane actions/choices, to its embracing of suspense mediocrity, with absurdities thrown in to achieve some twists. By no means is it a bad novel, it’s just not particularly special. It certainly didn’t live up to my expectations from its plot summary or marketing comparisons (the latter which are outright falsehoods.)

I expected this novel to fit into the ‘speculative’ realm more, with actual paranormal elements or at least more open-endedness in terms of what about the mystery of Silvertjarn was supernatural or conventional in explanation. For me (and probably other fans of fantasy, horror, or magic-realism) the choice to give The Lost Village an unabashedly conventional answer (and one with the intelligence and logic of a Scooby Doo cartoon episode at that) was a major let-down.

However, readers who simply adore dark thrillers whether simple, complex, or in-between will likely still love The Lost Village. I noticed one reviewer comparing the novel to a B movie, and that’s not far off. If you love suspense and don’t mind it stretching credulity, this is an engaging and quick read with some fantastic atmosphere. Those more partial to horror and speculative fiction, be more wary.

June 4, 2023

Out This Month: June

SHORT STORIES

“To Helen” by Bella Han, translated from the Chinese by the author (Clarkesworld, June 1).

“Matchstick Girl” by Lucas Santana, translated from the Portuguese by H. Pueyo (The Dark, June).

“Matchstick Girl” by Lucas Santana, translated from the Portuguese by H. Pueyo (The Dark, June).

NOVELS

Kappa by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated from the Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell (New Directions, June 6) [reprint]

Akutagawa’s Kappa is narrated by Patient No. 23, a madman in a lunatic asylum: he recounts how, while out hiking in Kamikochi, he spots a Kappa. He decides to chase it and, like Alice pursuing the White Rabbit, he tumbles down a hole, out of the human world and into the realm of the Kappas. There he is well looked after, in fact almost made a pet of: as a human, he is a novelty. He makes friends and spends his time learning about their world, exploring the seemingly ridiculous ways of the Kappa, but noting many—not always flattering—parallels to Japanese mores regarding morality, legal justice, economics, and sex. Alas, when the patient eventually returns to the human world, he becomes disgusted by humanity and, like Gulliver missing the Houyhnhnms, he begins to pine for his old friends the Kappas, rather as if he has been forced to take leave of Toad of Toad Hall…

May 13, 2023

2023

FEBRUARY

“Introduction to 2181 Overture, Second Edition” by Gu Shi, translated from the Chinese by Emily Jin (Clarkesworld).

“A Short Biography of a Conscious Chair” by Renan Bernardo, translated from the Portuguese by the author (Samovar).

APRIL

“The Librarian and the Robot” by Shi Heiyao, translated from the Chinese by Andy Dudak (Clarkesworld).

MAY

“Action at a Distance” by An Hao, translated from the Chinese by Andy Dudak (Clarkesworld).

“The Inside is Always Entrails” by Fernanda Castro, translated from the Portuguese by H. Pueyo (The Dark).

JUNE

“To Helen” by Bella Han, translated from the Chinese by the author (Clarkesworld).

“Matchstick Girl” by Lucas Santana, translated from the Portuguese by H. Pueyo (The Dark).

“A Pilgrimage to Memories Tattooed” by Elena Pavlova, translated from the Bulgarian by the author and Desislava Silvilova (Samovar).

“Plums in Chocolate” by Ernestas Parulskis, translated from the Lithuanian by Kotryna Garanasvili (Samovar).