Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog

October 3, 2025

Stanislaw Lem in Reactor

Alex Przybyla on “Stanislaw Lem’s Greatest Character: An Introduction to Ijon Tichy” (Reactor).

For more on Stanislaw Lem and Polish SFT, go here.

Out This Month: October

“Giant Grandmother” by Liu Maijia, translated from the Chinese by Blake Stone-Banks (Clarkesworld, October 1)

“Giant Grandmother” by Liu Maijia, translated from the Chinese by Blake Stone-Banks (Clarkesworld, October 1)

Black Hole Heart and Other Stories by K. A. Teryna, translated from the Russian by Alex Shvartsman (Fairwood Press, October 1)

The world is not how we perceive it. A blizzard may be the fury of a whale god. Intelligent bees watch our every move. Monsters lurk in the metro underpasses while others haunt our dreams. Are we asleep in frozen sarcophagi, en route to a new planet? Should we swallow jellyfish, drink colors, or repaint the sky? This book has the answers. But in return, it might steal your heart.

The Inner Harbour by Antoine Volodine, translated from the French by Gina M. Stamm (University of Minnesota Press, October 7)

A beguiling, perspective-shifting story of obsession and loss set in the grimy, late-colonial decadence of Macau at the end of the twentieth century.

The Lucky Ride by Yasushi Kitagawa, translated from the Japanese by Takami Nieda (Harper One, October 7)

The Lucky Ride by Yasushi Kitagawa, translated from the Japanese by Takami Nieda (Harper One, October 7)What if a single journey could change everything for you? What if it could lead you to new possibilities, help you reconnect with loved ones, or bring peace to your past? In this charming story, the unluckiest man in Japan is given a chance to flip his fortunes when a mysterious driver appears, offering him the opportunity to seize a new path. Life’s setbacks can often feel overwhelming, but in The Lucky Ride, you’ll embark on a journey of self-growth that shows us that luck isn’t something you’re born with—it’s a result of the choices you make and the positive energy you bring into the world.

Diving Board by Tomás Downey, translated from the Spanish (Argentina) by Sarah Moses (Invisible Publishing, October 7)

Tomás Downey writes from the edge of the abyss. A little girl disappears midair; a horse grows from a seed; a war widow receives a visit of condolence, over and over and over again. In “The Astronaut” a man has become weightless, bobbing around on the ceiling, nauseated every time he is brought down and tethered to the earth. But the question here is not “how” or “why,” it’s “what happens next?” The astronaut wonders “Will I burn like an asteroid or drown in the void of space?” just as all of Downey’s stories reside in that threatening, destabilizing moment when all connection is lost. The world is filled with an ever-thickening mist, an old love haunts the living, making fruit rot in the bowl, and resolution isn’t offered or even sought—the human condition is queasy, fretful, absurd. All we can hope for is the leap into the unknown.

Eye of the Monkey by Krisztina Tóth, translated by Ottilie Mulzet (Seven Stories Press, October 14)

Eye of the Monkey begins in the wake of a devastating civil war that led to the formation of the United Regency, an autocracy in an unnamed European country. The ravages of war are sweeping, and the populace has been divided into segregated zones, where the well-off are under mass surveillance and the poor are phantom presences, confined and ghettoized. On the verge of a nervous breakdown after being followed by a young man for weeks, Giselle, a history professor at the New University, seeks the help of Dr. Mihály Kreutzer, a psychiatrist who is navigating divorce and the recent death of his mother. They soon begin a torrid love affair, but everything is not what it seems. As Giselle begins to unpack her family history and the possible root of her psychological crisis, Dr. Kreutzer, who has ties to some of the most powerful people in the country, possesses ulterior motives of his own.

Sea Now by Eva Meijer, translated from the Dutch by Anne Thompson Melo (Two Lines Press, October 14)

Sea Now by Eva Meijer, translated from the Dutch by Anne Thompson Melo (Two Lines Press, October 14)The catastrophe that everyone knew was coming has arrived—the dykes are breached, the tideline rises a kilometer a day, and the citizens of the Netherlands are forced into gyms and shelters in Germany and Belgium. The foxes and rabbits head inland across the dunes. The politicians make empty speeches and fret the optics. The Hague—“the center of peace and justice”—slips beneath the rising water. Online retailers do flash sale promotions on disaster kits. There is violence and looting, but some people are too tired to start over again and simply walk into the rising tide. Not willing to simply move on, three women get into a small boat and ride back out over the flooded cities, looking for loved ones they know are likely drowned. On the way, they witness a world retaken by seabirds, whales, and kelp forests. The sea has spoken, and there’s nothing left to be done but listen

The Call of the Friend by JaeHoon Choi, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (Honford Star, October 17)

The Call of the Friend by JaeHoon Choi, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (Honford Star, October 17)University student Wonjun visits his friend Jingu’s basement apartment, only to find unsettling changes that are somehow tied to a K-pop star’s suicide. Jingu behaves coldly, a strange statue looms in the corner, and reality begins to fracture. Blurring the lines between hallucination and nightmare, this graphic novel by JaeHoon Choi explores guilt and despair through a Lovecraftian lens, creating a haunting tale of emotional and cosmic horror.

The New Eve by Moussa Ould Ebnou, translated from the French and Arabic by Paul Roochnik (Iskanchi Press, October 20)

The New Eve is a haunting and philosophical speculative novel that delves into the core of what it means to love, to resist, and to be human in a technologically dominated future. Set in a totalitarian society where human reproduction is mechanized, emotional bonds are forbidden, and gender identity is strictly controlled, this visionary story imagines a world devoid of connection—and the rebellion that stirs within. Adam and Maneki, two outliers in this hyper-controlled world, form a bond that defies the laws of their society. As they struggle against a system that criminalizes affection and individuality, they encounter androgynes who exist outside the binary, challenging the regime’s rigid definitions of identity and desire. Through their journey, the story examines the suppression of love, the ethics of technological advancement, and the resistance that grows from within the human spirit.

Darker Days by Thomas Olde Heuvelt, translated from the Dutch by ? (Harper, October 28)

Darker Days by Thomas Olde Heuvelt, translated from the Dutch by ? (Harper, October 28)Sometimes you think you can see things behind the fence. Bad things. So it’s better not to look . . . In Lock Haven, a quiet little town in Washington State, Bird Street is a special place. The residents of this pretty cul-de-sac on the edge of the woods are all successful, healthy, and happy. Their children are prodigies; well-mannered and… unnaturally smart. But come November, the “Darker Days” descend, bringing accidents, bad luck, conflict, and illness. Luana and Ralph Lewis-da Silva prepare for this, and so do their children Kaila and Django. It is in November when a stranger appears to collect on a longstanding debt. A price must be paid for the good fortune they enjoy the rest of the year. A sacrifice must be made. So it has been for over a century. To assuage their guilt, the residents of Bird Street choose carefully who will be sent into the woods. Usually, it is an elderly or terminally ill individual who wishes to die with dignity and is content to be helped on their way. But this year, things don’t go to plan, and events take a terrifying turn . . .

Blood for the Undying Throne by Sung-il Kim, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur (Tor, October 28)

Blood for the Undying Throne, the sequel to Blood of the Old Kings, from award-winning Korean author Sung-il Kim and translated by the world-renowned Anton Hur, is an epic fantasy adventure where the corpses of sorcerers power an empire and ordinary people rise up to tear it down.

The Voice of Blood by Gabriela Rábago Palafox, translated from the Spanish by M. Elizabeth Ginway and Enrique Muñoz-Mantas

A groundbreaking collection of short stories that intertwines themes of identity, desire, trauma, and transformation with a haunting gothic sensibility. The stories within explore deeply personal and globally resonant themes, from gender-based violence and ecological precarity to social taboos and the vulnerability of marginalized identities. A pioneer in the wave of Latin American writers revitalizing literary horror to confront contemporary political and environmental crises, Rábago Palafox reimagines gothic traditions through a feminist lens, using the vampire to show women as empowered rather than victimized. Her stories deftly balance the speculative, queer, and deeply human, offering readers a chilling yet thought-provoking exploration of societal anxieties, identity, and memory.

September 30, 2025

Review: Blood for the Undying Throne by Sung-il Kim

(The Bleeding Empire #2)

translated by Anton Hur

original publication (in Korean): ?

first English edition: 2025, Tor

384 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Blood for the Undying Throne, the second in Sung-il Kim’s Bleeding Empire series, continues the story of provincial struggle against imperial domination. As in Blood of the Old Kings, Kim organizes his chapters around specific characters, but this time, those characters are Prince Emere of Kamori, Arienne (again), and Yuma, the Chief Herder of Danras, which was destroyed by the Star of Mersia over a century before.

The novel picks up with Prince Emere continuing to search for his destiny, this time in the Empire’s capital city. After fighting side by side with Loran in Arland, Emere has come to the capital to represent Kamori but very quickly finds himself the target of an assassin. Through a series of visions given to him by Cain (one of the main characters of Blood of the Old Kings), who has become a part of the Circuit of Destiny, Emere learns about a plot by the Office of Truth to stage a coup and take over the Empire. Emere, because of the part he is to play in the future, has become a target and twice escapes assassination.

Meanwhile, Arienne has journeyed to Danras (part of Mersia) to find out what happened to that country a century ago. Everyone knows that it was wiped out by a terrible weapon, but both Eldred (former ruler of Mersia) and Lysandros (former Grand Inquisitor of the Empire) lay the blame at one another’s feet. As Arienne moves around Danras, she encounters what seems like a mad Power Generator gathering up remnants. It attacks her, and in escaping it she finds herself in the catacombs and meets the ghost of Noam, an imperial soldier who was killed when the Star of Mersia was unleashed.

We finally learn what happened to Mersia through the chapters that focus on Yuma, Chief Herder of Danras and later lover of Chief Inquisitor Lysandros. Having decided, with most of the people of Danras, to throw off the several-hundred-year yoke of Eldred’s tyranny and terror, Yuma joins forces with the Empire’s Grand Inquisitor to defeat Eldred. Not fully realizing the consequences until after Eldred is vanquished, Yuma soon understands that without Eldred, Danras no longer needs a Host (a sorcerer who protected the people from Eldred as best he could) or a Chief Herder, since much will change once the Empire establishes itself in that country. Yuma gives birth to Tychon (whom we meet in the first book) after the battle, but the final showdown between Eldred and Lysandros spells destruction for the whole region.

We learn Yuma’s story partly through her chapters but also partly through Arienne’s experiences, especially as she expands her powers in order to build more structures in her mind to house the ghosts she meets. She brings Noam into her mind and sets him up in the room with Tychon so that the former can help care for the latter. Eventually, Arienne figures out how to reconstruct Danras in her memory, through the help of the ghosts she meets there, and keeps the country’s people and traditions in there as a way to maintain them as long as she lives.

Back in the capital, Emere must find a way to stop the Office of Truth from unleashing the Star of Mersia once more in its bid to take over the Empire. Help comes from King Loran herself, who has come to the capital to meet with the Ebrians, a group that has maintained its religion despite the Empire’s crackdown on gods and sorcerers. Emere has been trying his whole life to find out what fate holds for him, but this final showdown with the Empire gives him his answer.

Blood for the Undying Throne offers answers several questions raised in the first book, helping us understand what really happened in Mersia between Lysandros and Eldred, and how Eldred came to be locked in the basement of the Academy in the first place. We see how Arienne has grown more confident in her powers and we learn more about Emere’s past, including his relationship with the Ebrian Rakel and the continuing efforts of various provinces to resist the Empire. Destiny, memory, love, and friendship guide this story and give the reader the sense that, despite the evils of rulers like Eldred and the Empire itself, people who believe in freedom and integrity will ultimately prevail.

Overall, this second book in Kim’s fantasy series is entertaining and draws the reader in quickly, thanks especially to Anton Hur’s skillful translation. This reader looks forward to further books in the Bleeding Empire series.

September 27, 2025

Yuki Tejima on Translating Mizuki Tsujimura

On LitHub, translator Yuki Tejima talks about translating Mizuki Tsujimura’s Lost Souls Meet Under a Full Moon (Scribner) into English.

September 17, 2025

Review: The Wax Child by Olga Ravn

translated by Martin Aitken

original publication (in Danish): 2023

first English edition: 2025, New Directions

144 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

This small, strange, polyphonic book refuses to settle down into something knowable. As someone who’s learned about and read multiple texts about the (American) witch hunts of the 17th century, I, understandably, approached this novel about a woman and her friends accused of witchcraft with the belief that The Wax Child would offer yet another narrative of doubt and criticism. Of course these women weren’t going to be witches because such accusations were often unfounded and those who were accused were just scapegoats for the fears of a community.

Ravn, whose intriguing short novel The Employees (2022) about humans and humanoid robots exploring a strange planet, is nothing if not aggressively imaginative. From the beginning, The Wax Child unsettles our assumptions since, well, it’s narrated by a wax doll. We’re never told why Christenze Kruckow, an unmarried noblewoman living in 17th-century Denmark, has created this doll, but she sure does enjoy having it around. In fact, she and her friend insert various bits and pieces of fingernail, hair, etc. in the doll’s foot sometimes, which sounds…strange. Are they trying to practice some sort of witchcraft, though they aren’t actually witches? Or is this some sort of game? One of Christenze’s friends then takes the doll, and that friend’s daughter spends a lot of time with it, pretending to feed it and otherwise playing with it.

When a women in the household where the poor but noble Christenze lives accuses her of being a witch, the latter flees to a larger Danish city. She and the women she meets there, though, ultimately fall prey to the political establishment that, once it hears one whisper of witchcraft, start the proceedings to find out who has been practicing it. The entire narrative, though, is in the voice of the wax child, clearly more than just a doll. Its sing-song language, almost like an incantation, reflects the fact that Ravn drew upon letters, magical spells, manuals, court documents, and grimoires to come up with this story.

Split into two parts (Christenze’s life before she is accused and her life afterwards), The Wax Child can be read in one sitting, a dark, swirling, disconcerting narrative in which the women laugh at those who accuse them and yet practice rituals where it’s unclear if these are just suggestions for health and relationships based on lore or if they’re designed to be used as witchcraft. Ravn absolutely refuses to clarify, resulting in a story that draws us into an older world where these questions were likely never answered, either.

September 16, 2025

Review: Eye of the Monkey by Krisztina Tóth

translated by Ottilie Mulzet

original publication (in Hungarian): 2022

first English edition: 2025, Seven Stories Press

304 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Eye of the Monkey, Hungarian author Krisztina Tóth’s first novel to be translated into English, could have been one of the best works of SFT of 2025. Its exploration of government oppression, memory, history, education, relationships, and environmental catastrophe set it up to be a timely, fascinating look at an unnamed society’s descent into isolation and paranoia. Instead, the book is a series of seemingly-disconnected portraits of several different characters, all of whom are struggling with some sort of loss. Only at the end do we understand how they all fit together, but by that point, this reader had lost interest.

Set in an unnamed country at some point in the future, Eye of the Monkey focuses on a psychiatrist, Dr. Mihály Kreutzer, and his patient, Gizella, as they each have to deal with their own familial problems and then begin their own complicated and disturbing relationship. A sex addict who records his many conquests in notebooks, complete with lewd pictures and descriptions, Kreutzer is also a good friend to the Regent, who, since the end of the Civil War, has presided over the United Regency. Apparently Kreutzer has been treating the Regent’s wife for her bipolar issues and the Regent himself for other problems. Since the end of the war, the wealthy and well-to-do live in “protected zones,” while the poor are left to fight over scraps in the dangerous areas.

Meanwhile Gizella, a professor of Modern History at the New University, is unhappy in her marriage to an older, predictable man and is also being followed by a young man who claims she is his mother. In the course of her talks with Kreutzer, we learn that her parents divorced when she was young and her sister went to live with her father. Though she discusses this almost without emotion, her description of what happened reveals that the incident affected her profoundly.

Kreutzer himself is in the process of getting divorced, and when his mother passes away, he is stuck cleaning out her cramped, dirty apartment. In the process, he remembers what happened when his younger brother died, and his tone is similar to Gizella’s when she talks about her own past.

Both Kreutzer and Gizella are members of the well-to-do class, living in protected zones and benefiting from special IDs that allow them to travel freely and shop in certain stores. Apparently, after the establishment of the Unified Regency, very few people have been allowed to leave the country. The main characters, all middle-aged, very clearly remember what life was like before the war, when shops and streets were filled with people. We get the sense that they are just stopping themselves from tipping over into nostalgia, as if even that thought would get them in trouble.

One of the most disappointing things about this book is how Tóth never follows through on the intriguing trope of brain/body disconnection. Early in the novel, we learn that Kreutzer feels that though “he was psychically well-balanced, with a nearly detached relationship to his own body, he was observing the signs of his own aging with anxiety.” Later on, we learn that his favorite image, which he has hung on the wall throughout his life, is of a monkey who had been part of a famous head-transplant experiment in 1970. The portrait of the monkey grips Kreutzer because it shows

that moment when the wondering, dumbfounded soul, clashing with the impossibilities of this world, arrived, or more precisely returned to a fractured, tortured body stitched together from two parts. This is what had enthralled the doctor so much, even as a schoolboy, and what he had clung to ever since then: this image enshrining that moment of awakening.

One gets the sense that all of the characters depicted in this novel–Kreutzer and Gizella, their spouses, the cleaning lady, Kreutzer’s mother, the man who follows Gizella, the Regent himself–are like this monkey in that they are made up of two halves working together but not in harmony. The story itself, too, seems to work in this way, with lyrical passages like the one just quoted dropped in to a larger narrative in which events are described in a plodding, laborious way. One wonders, for example, exactly what the point is of the long passage near the end about Kreutzer trying to put together a sleep sofa.

In keeping with the secrecy and oppression that governs this country, a catastrophic failure at one of the power plants threatens everyone, but the people are told only to stay indoors. Kreutzer, we learn, has been tasked with interviewing people who are willing to go on a suicide mission to help contain the problem. By the time the government realizes the extent of the threat, it’s already too late to evacuate everyone and get them to safety. The novel ends with Kreutzer himself being told that he, too, must put himself in danger, otherwise his sexual escapades will be made public.

Tóth depicts a society of lost souls, wandering around looking for meaning, feeling detached from their pasts (which still haunt them) but struggling to move forward in order to raise children and pursue relationships. Nonetheless, the novel never brings the various threads together into a coherent, compelling narrative that makes us care about what happens to the characters.

September 9, 2025

Review: Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin

translated by Megan McDowell

original publication (in Spanish): 2025

first English edition: 2025, Knopf

192 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

*spoilers*

Good and Evil and Other Stories is Samanta Schweblin’s fifth book in English, after Fever Dream (2017), Mouthful of Birds (2019), Little Eyes (2020), and Seven Empty Houses (2022), all translated by Megan McDowell. Schweblin’s signature style provokes a sense of dread and disorientation in the reader, with characters who find it difficult to trust reality or their own senses, wandering through a (figuratively) dark landscape where people form uncertain or unexpected relationships that don’t end well. Ranging from novels about voyeuristic technology and destructive pesticides to collections with stories about dysfunctional families and loneliness, Schweblin’s oeuvre offers Anglophone readers an enlightening glimpse into the world of Spanish-language SFT.

Usually, collections take their titles from one of the included stories, but Good and Evil includes no such story, thus deliberately prompting the reader to think about this dichotomy while reading the six haunting Schweblinesque tales. Of course, none of these stories is a straightforward meditation on good and evil. Rather, they invite us to think about our own understanding of those words and ask if we would then apply those terms to the characters in the stories. “Welcome to the Club” is an unnerving piece about a woman who tries to drown herself, but realizes that it’s not working, comes back up to the surface, and resumes her daily life (taking care of her husband and two daughters), but with a sense of desperation. Apparently, her neighbor, a single man who erected a barricade around his house, witnessed her attempt and implies that he, too, found himself unable to commit suicide. His advice to her moving forward? Calm down and then find ways to provoke pain in someone you love, presumably to start feeling something again. The nameless narrator then decides to kill her daughters’ pet rabbit, but just as she is about to do it, she hesitates, and as the rabbit escapes, she feels a sense of freedom.

Like “Welcome to the Club” (the first story in the collection), the last (“A Visit from the Chief”) features a woman desperately trying to convince herself that her life is fine. Meanwhile, she misses her daughter and finds her work meaningless. When a woman from the same senior home her mother lives in wanders out of the building and onto a train, the narrator feels obligated to take her to her apartment until the old woman can be picked up and taken home. What follows is shocking and yet also invigorating to the narrator–the woman’s son comes to the apartment, trashes it, threatens the narrator with a gun, but says that what he does is help people. He demands that the narrator tell him how he can help her, and eventually she puts into words the pain that she has felt over her nonexistent relationship with her daughter.

Both “A Fabulous Animal” and “The Woman from Atlantida” feature women filled with regret over tragic incidents that happened decades before. In the former, Leila receives a call from her friend following years of silence. Over the course of the conversation, we learn that Leila had visited Elena a few times after the latter had gotten married and had a child. This child (at seven years old), Leila realized on the last visit, was unusual and remarkable, and in the course of talking to him, she learned that he didn’t want to be an architect like his parents, but a horse. The two joked around pretending to be horses, but then Peta tried to walk on the balcony railing and fell to his death. Strangely enough, as the boy’s body was being taken away, further up the street, a horse that Leila had seen earlier that day is also lying in the street. She pays to have it cared for, and the whisper along the edges of the story is that the boy somehow figured out how to have a connection with, or become?, a horse in the end. In “The Woman from Atlantida,” two sisters on vacation stumble upon a poet who has tried to kill herself twice. The sisters visit her every night, clean up her house, and try to get her to stop drinking in order to help her start writing again. Tragically, on the night that the poet is finally able to leave the house, she and the narrator’s older sister run into the ocean, with terrible consequences.

“William in the Window,” like “A Fabulous Animal,” has at its heart a mystery tied up with an animal. Here, space and time seem to fold together. A woman living in Shanghai on a writer’s retreat meets a colleague (Denys) who is unusually connected to her cat William. When she learns that the cat has died back in Ireland, Denys becomes intensely depressed but then believes that she can hear William running around in her studio. At first, the narrator thinks this is just grief, but then she, too, hears what sounds like a cat rooting through the apartment. Then, the narrator sees her husband’s handprint on the bathroom wall, though he is thousands of miles away.

Finally, in “An Eye in the Throat” (first published in English in the Paris Review, 2024), a father lives for years with regret after his son accidentally swallows a battery and must undergo a tracheotomy. During one of the family’s long trips to a hospital, the boy manages to get lost and winds up being taken care of by a gruff couple at a gas station. For decades after that, the boy’s father receives phone calls from someone who doesn’t say a word and eventually hangs up. Believing this to be the man from the gas station, the father eventually finds these silent calls comforting. Following this incident, the son seems to withdraw from his father. After his son grows up and begins his own life and his wife goes off to lead hers, the father finds his way back to the gas station and the same strange couple. The man shows the father where the phone was that the boy could have used to call his parents, but the man asks how his son could have used the phone when he couldn’t speak. At that point, the man (and the reader) gets the strange feeling that, all these years, that silent phone call has been from his son, a physical manifestation of the boy’s attempt to reconnect with his father.

Regret, guilt, pain, and desperation form the backbone of these stories, with families and relationships that are strained often because of a lack of communication and understanding. Schweblin never disappoints, offering compelling, strange stories that stay with the reader long after they’re over.

September 6, 2025

Out This Month: September

Sympathy Tower Tokyo by Rie Qudan, translated from the Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood (S&S/Summit Books, September 2)

Sympathy Tower Tokyo by Rie Qudan, translated from the Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood (S&S/Summit Books, September 2)Welcome to the Japan of tomorrow. Here, the practice of radical sympathy toward criminals has become normalized. The incarcerated are considered victims influenced by their environments to commit crime and are labeled accordingly as Homo miserabilis. A grand, yet controversial, skyscraper in the heart of Tokyo is planned to house lawbreakers in compassionate comfort—Sympathy Tower Tokyo. Acclaimed architect Sara Machina has been tasked with designing the city’s new centerpiece but is filled with doubt. Haunted by a terrible crime she experienced as a young girl, she wonders if she might inherently disagree with the values of the project, which should be the pinnacle of her career. As Sara grapples with these conflicting emotions, her relationship with her gorgeous—and much younger—boyfriend grows increasingly strained. In search of solace and in need of creative inspiration, Sara turns to the knowing words of an AI chatbot…

The Collected Stories by Cixin Liu, translated from the Chinese by various translators (Head of Zeus, September 11)

From cosmological horror to wry satire, from first contact to the end of everything, these 32 stories explore our place in the universe, pitting the vastness of space against the fragility of humanity. The scale of Liu’s imagination is immense, exploring both the infinite and the infinitesimal, the epic and the intimate. Here, machine intelligences create art or sow terror, humanity is annihilated or created anew, alien civilizations come bearing gifts, or they come in the cold logic of universal war. Solar systems are devoured, planets are turned into spaceships, and time is reversed.

Castigation by Sultan Raev, translated from the Kyrgyz by Shelley Fairweather-Vega (Syracuse University Press, September 15)

Castigation by Sultan Raev, translated from the Kyrgyz by Shelley Fairweather-Vega (Syracuse University Press, September 15)Seven escaped mental patients—including reincarnations of Genghis Khan, Cleopatra, and Alexander the Great—trudge across a nameless landscape, pursued by an omnipresent snake and haunted by their past lives’ brutal transgressions. Led by a mysterious Emperor who promises deliverance to the Holy Land, these travelers are actually pilgrims of their own fractured histories, each confronting the violent, sensual, and deeply human moments that have defined their existence.

Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell (Knopf, September 16)

Good and Evil and Other Stories by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell (Knopf, September 16)The characters of Good and Evil find themselves at a point of no return, dazzled by the glare of impending tragedy. Vulnerable and profoundly human, they become trapped in the instant in which the uncanny has lurched into their lives. Some are transformed, some are isolated, others waver between guilt or tenderness. All of them are riven by uncertainty. Schweblin’s prose uses tension and truth to construct a literary universe in which the monsters of everyday life come so close to us that we can almost feel their breath. Her writing provokes awe and disquiet, a state of alarm that at the same time transports us to a hypnotic world as recognizable as it is strange.

The Event by by Juan José Saer, translated from the Spanish by Helen R. Lane (Open Letter, September 23)

Blanco the Magician is renowned across Europe for his astonishing telepathic feats, dazzling audiences with the power of his mind. But when a ruthless conspiracy exposes him as a fraud, his carefully constructed world shatters. Fleeing disgrace, Blanco escapes to the remote corners of Argentina, where he begins a new life in obscurity with the beguiling and enigmatic Gina. As Blanco struggles to rebuild his identity, he finds himself entangled in a series of events that blur the line between illusion and reality. In The Event, Juan José Saer weaves a hypnotic tale of deception, exile, and the search for meaning in a world where nothing is as it seems. With his signature philosophical depth and luminous prose, Saer explores themes of love, identity, and the fragile constructs that hold our lives together.

Archipelago of the Sun by Yoko Tawada, translated from Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions, September 23)

Archipelago of the Sun by Yoko Tawada, translated from Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions, September 23)Archipelago of the Sun finds Hiruko still searching for her lost country, traveling around the Baltic on a mail boat. With her are Knut, a Danish linguist; Akash, an Indian in the process of moving to the opposite sex; Nanook, a Greenlander who once worked as a sushi chef; Nora, the German woman who loves Nanook but is equally concerned with social justice and the environment; and Susanoo, a former sushi chef who believes he is responsible for the entire group. But weren’t they originally supposed to sail to Cape Town, and then on to India? Puzzled by this sudden change in route, which no one seems to remember anything about, they encounter long dead writers (Witold Gombrowicz, Hella Wuolijoki) on board, plus a cast of characters from literature, art, and myth. As the very existence of Hiruko and Susanoo’s homeland is called into question, Susanoo meets the mythical princess he will marry, and Hiruko tells the others that she will now be a house in which everyone can live. Though the trilogy comes to its end, their journey seems likely to continue.

Crossroads of Ravens by Andrzej Sapkowski, translated from the Polish by David French (Gollancz, September 30)

Witchers are not born. They are made. Before he was the White Wolf or the Butcher of Blaviken, Geralt of Rivia was simply a fresh graduate of Kaer Morhen, stepping into a world that neither understands nor welcomes his kind. And when an act of naïve heroism goes gravely wrong, Geralt is only saved from the noose by Preston Holt, a grizzled witcher with a buried past and an agenda of his own. Under Holt’s guiding hand, Geralt begins to learn what it truly means to walk the Path – to protect a world that fears him, and to survive in it on his own terms. But as the line between right and wrong begins to blur, Geralt must decide to become the monster everyone expects, or something else entirely. This is the story of how legends are made – and what they cost.

The Sugar Kremlin by Vladimir Sorokin, translated from the Russian by Max Lawton (Dalkey Archive Press, September 30)

Presenting a wide variety of genres and tones, The Sugar Kremlin lays out a frightening vision of speculative mercilessness and carnivalesque political horror. The Sugar Kremlin is the follow-up to Vladimir Sorokin’s Day of the Oprichnik, taking place in the same New Medieval universe over the course of fifteen chapters that all return to the object of the title: replicas of the Moscow Kremlin made of sugar. Thousands of these creations are given away to children during the holidays, then make their way through each stratum of Russian society. We follow the trajectories of these candied gifts from the hands of harried paupers to secret political dissidents, from torture-obsessed civil servants to sex workers in a nearby bordello… As Sorokin shifts from story to story and style to style, he draws the reader through grotesquely Russian scenes, creating an aberrantly metaphysical encyclopedia of the New Medieval “Russian soul.” The candy’s sweetness is deceptive—underneath it, you may detect notes of blood and excrement.

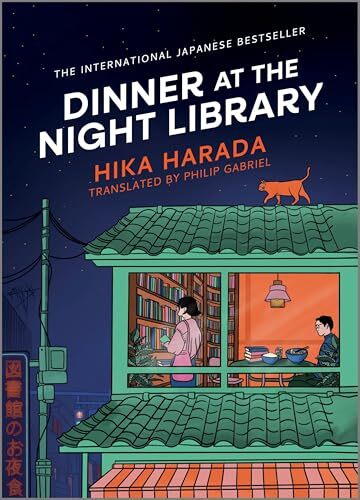

Dinner at the Night Library by Hika Harada, translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel (Hanover Square Press, September 30)

Dinner at the Night Library by Hika Harada, translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel (Hanover Square Press, September 30)All Otaha Higuchi wants to do is work with books. However, the exhausting nature of her work at a chain bookstore, combined with her paltry salary and irritating manager quickly bring reality crashing down around her. She is on the verge of quitting when she receives a message from somebody anonymous, inviting her to apply for a job at ‘”The Night Library.” The hours are from seven o’clock to midnight. The library exclusively stores books by deceased authors, and none of them can be checked out – instead, they’re put on public display to be revered and celebrated by the library’s visitors, making it akin to a book museum. There, Otoha meets the other staff, a group of likeminded literary misfits, including a legendary chef who prepares incredible meals for the library’s employees at the end of each day. Night after night, she bonds with her colleagues over meals in the café, each of which are inspired by the literature on the shelves. But as strange occurrences start happening around the library that may bring the threat of its closure, Otaha and her friends fear that the peace they have found there will forever be lost to them. Will their faith in the value of books strong enough to save it? And what will remain if it isn’t?

The Wax Child by Olga Ravn, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken (New Directions, September 30)

The Wax Child by Olga Ravn, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken (New Directions, September 30)In seventeenth-century Denmark, Christenze Kruckow, an unmarried noblewoman, is accused of witchcraft. She and several other women are rumored to be possessed by the Devil, who has come to them in the form of a tall headless man and gives them dark powers: they can steal people’s happiness, they have performed unchristian acts, and they can cause pestilence or even death. They are all in danger of the stake. The Wax Child, narrated by a wax doll created by Christenze Kruckow, is an unsettling horror story about brutality and power, nature and witchcraft, set in the fragile communities of premodern Europe.

REVIEWS

Lost Souls Meet Under a Full Moon at Lightspeed

August 21, 2025

Arkady Strugatsky at SF Ruminations

Here’s my joint-SFT review with Joachim Boaz over at Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations, this time on Arkady Strugatsky’s “Wanderers and Travellers” (1963, trans. 1966). Check it out here!

The Strugatskys at SF Ruminations

Here’s my joint-SFT review with Joachim Boaz over at Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations, this time on Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s “Wanderers and Travellers” (1963, trans. 1966). Check it out here!