Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 5

October 4, 2024

Out This Month: October

“The Face of God: A Documentary” by Damián Neri, translated from the Spanish by the author (Clarkesworld, October 1)

“The Face of God: A Documentary” by Damián Neri, translated from the Spanish by the author (Clarkesworld, October 1) The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken (Penguin Press, October 1)

The Third Realm by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken (Penguin Press, October 1)Shapeshifting visitors, unsolved murders in the forest, black metal bands and an online bank of thousands of people’s dreams—the star is back. Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The Morning Star kept readers up all night, immersed with nine characters whose individual lives are heightened by the sudden appearance of a blazing new star, and The Wolves of Eternity portrayed the intimate experiences of two estranged half siblings decades before the star rises. In The Third Realm, the effects of the star are felt around the world, as people start to reckon with what it might possibly mean. With this next novel, the limitless scale and ambition of Knausgaard’s new universe is clear. This is life, death, the human condition and the real-time creation of an epic and utterly immersive world.

Blood of the Old Kings by Sung-il Kim, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur (Tor Books, October 8)

Blood of the Old Kings by Sung-il Kim, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur (Tor Books, October 8)In an Empire run on necromancy, dead sorcerers are the lifeblood. Their corpses are wrapped in chains and drained of magic to feed the unquenchable hunger for imperial conquest. Born with magic, Arienne has become resigned to her dark fate. But when the voice of a long-dead sorcerer begins to speak inside her head, she listens. There may be another future for her, if she’s willing to fight for it. Miles away, beneath a volcano, a seven-eyed dragon also wears the Empire’s chains. Before the imperial fist closed around their lands, it was the people’s sacred guardian. Loran, a widowed swordswoman, is the first to kneel before the dragon in decades. She comes with a desperate plea, and will leave with a sword of dragon-fang in hand and a great purpose before her. In the heart of the Imperial capital, Cain is known as a man who gets things done. When his best friend and mentor is found murdered, he will leave no stone unturned to find those responsible, even if it means starting a war.

Waiting for the Fear by Oğuz Atay, translated from the Turkish by Ralph Hubbell (NYRB Classics, October 22)

Waiting for the Fear by Oğuz Atay, translated from the Turkish by Ralph Hubbell (NYRB Classics, October 22)A giant of modern Turkish literature, Oğuz Atay remains largely untranslated into English. First published in 1975, Waiting for the Fear is Atay’s only collection of short stories, praised by the Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk for having transformed the art of short fiction. Atay’s stories are vivid with life’s absurdities and psychologically true to life, while his characters, oddballs and losers all, are utterly individual. A brilliant examiner of the inner life, Atay is no less aware of the flawed social world in which his people struggle to make their way, and he is exceptionally attuned to the strange power storytelling itself can exert over fate. In the title story, a nameless young man returns to his home on the outskirts of an enormous nameless city to discover that he has received a letter in a language he neither knows nor recognizes—after which, step by step, the inscrutable missive reshapes his world. In “Railroad Storytellers: A Dream,” a professional story peddler lives in a hut beside a train station in a country that is at war—unless it isn’t. He can’t remember. What do such life and death realities matter, however, so long as there are stories to tell?

September 20, 2024

Review: Metropole by Ferenc Karinthy

translated by George Szirtes

original publication (in Hungarian): 1970

this edition (in English): Telegram, 2010

236 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Ferenc Karinthy’s Metropole will make you a nervous wreck—that is, if the thought of being trapped in a strange city and unable to communicate with anyone makes you feel nervous. It certainly gives me that feeling. And while the label “Kafkaesque” has been thrown around a lot over the last couple of decades, it perfectly describes this story of a hapless linguist fighting against a sea of uncaring humanity in an effort to find his way home.

Karinthy, the son of the famous Hungarian satirist Frigyes Karinthy, wrote Metropole during the Cold War. Hungary’s own history with the brutality of Communist rule (especially during the 1956 crackdown of Hungarian revolutionaries) informs Metropole, especially in the last scene where a large number of people rise up against the government and then are summarily crushed, the traces of their rebellion almost completely swept away.

Metropole begins with an accomplished linguist, Budai, falling asleep on a plane on his way to a conference in Helsinki and waking up in a strange country. Armed only with his carry-on bag and passport, Budai is pushed by the crowd out of the airport and onto the street. He eventually finds a hotel and tries to ask the receptionist how he can get back to the airport and Helsinki. Everything happens so fast—the receptionist takes his passport (which Budai never sees again) and when Budai holds out some money (as a bribe), the receptionist thrusts local currency into his hands and moves on to the next customer. Budai is shoved aside by the hostile and almost violent crowd and makes his way to his room to think.

The crowds, themselves, are a major feature of this book, including such a wide variety of races and ethnicities that the linguist is utterly unable to determine in what part of the world he has landed. The language the people speak is unintelligible—being a linguist, Budai tries a wide variety of different languages from all around the world, but to no avail. Even his knowledge of ancient Greek and long-dead languages don’t help him. The writing, too, is a complete mystery, despite Budai buying a newspaper and a map and using all of his skills to try and decode them.

In the meantime, he needs to eat, but finds himself stuck in extremely long lines everywhere he goes. The crowds rarely seem to thin out, and the people in them have no compunction about elbowing, shoving, and kicking anyone who gets in their way. Eventually Budai finds a grocery store and takes his dinner back to the hotel. From then on, the linguist tries a variety of tactics to find a way out—he screams at the receptionist, gets himself arrested, and then catches the eye of the elevator operator, who seems to take pity on him. Her name, which she pronounces differently every time she says it, is the title of the Hungarian version of the novel (Epepe). Budai manages to learn a few numbers and phrases from Epepe, but that’s it.

Running out of money, kicked out of the hotel, and desperate, Budai winds up working as a day laborer and living on the streets, only to then get caught up in what seems like a revolution that is quickly put down. His discovery of a river, almost a month after arriving, gives him hope that he’ll be able to find his way out of this unknowable country/city and back home.

Of course, Karinthy’s story can be read in a multitude of ways: as a dream, a hallucination, an allegory, a story of alien abduction, etc. The completely unintelligible language suggests (and Budai even entertains the notion for a minute) that the linguist isn’t even on Earth anymore. No matter how hard he tries, he can’t seem to find the outskirts or city limits, as if the strange place never ends. And even though he regularly sees airplanes overhead, he can never find an airport or a harbor. Only the subway allows him to explore the area, but even that doesn’t help him much. One could read Metropole as an allegory about the inability to truly communicate, even if one understands the language. The protagonist’s disorientation, his inability to escape, and the brutality of the crowds invite one to read the book as portrait of what it felt like to live under Communism in Hungary.

Despite the anxiety that this book will likely provoke, you’ll find yourself unable to put it down. The translation is so smooth and skillful that one can easily forget that it wasn’t originally written in English (how appropriate!).

September 1, 2024

Out This Month: September

“The Children I Gave You, Oxalaia” by Cirilo Lemos, translated by Thamirys Gênova (Clarkesworld, September 1)

“The Children I Gave You, Oxalaia” by Cirilo Lemos, translated by Thamirys Gênova (Clarkesworld, September 1) The Night Guest

by Hildur Knútsdóttir; translated from the Icelandic by Mary Robinette Kowal (Tor Nightfire, September 3)

The Night Guest

by Hildur Knútsdóttir; translated from the Icelandic by Mary Robinette Kowal (Tor Nightfire, September 3)The Night Guest is an eerie and ensnaring story set in contemporary Reykjavík that’s sure to keep you awake at night. Iðunn is in yet another doctor’s office. She knows her constant fatigue is a sign that something’s not right, but practitioners dismiss her symptoms and blood tests haven’t revealed any cause. When she talks to friends and family about it, the refrain is the same — have you tried eating better? exercising more? establishing a nighttime routine? She tries to follow their advice, buying everything from vitamins to sleeping pills to a step-counting watch. Nothing helps. Until one night Iðunn falls asleep with the watch on, and wakes up to find she’s walked over 40,000 steps in the night . . .What is happening when she’s asleep? Why is she waking up with increasingly disturbing injuries? And why won’t anyone believe her?

No/Mad/Land by Francesco Verso, translated from the Italian by Sally McCorry (Flame Tree Publishing, September 10)

The Pulldogs leave Rome to embrace a new condition: leaving no trace of their passage, they shape a new challenging lifestyle: wandering around the world as neo-nomads to spread their solarpunk way of living and to engage on a never-ending mission to save endangered human cultures with nanites. But the vision of Alan and Nicolas about how the Pulldogs should live collide, and as a consequence, they split in two groups: one goes North to live in the beautiful wilderness of Siberia and Mongolia, while the other goes South to save the Dogon tribe from a possible extinction due to climate change in Central Africa. But at the end everybody – including a new generation of Pulldogs – will have to come back to Rome, where their incredible transformation started many years before. Sequel to the celebrated The Roamers.

A Sunny Place for Shady People by Mariana Enriquez, translated from the Spanish (Argentina) by Megan McDowell (Hogarth, September 17)

A Sunny Place for Shady People by Mariana Enriquez, translated from the Spanish (Argentina) by Megan McDowell (Hogarth, September 17)In twelve spellbinding new stories, Enriquez writes about ordinary people, especially women, whose lives turn inside out when they encounter terror, the surreal, and the supernatural. A neighborhood nuisanced by ghosts, a family whose faces melt away, a faded hotel haunted by a girl who dissolved in the water tank on the roof, a riverbank populated by birds that used to be women—these and other tales illuminate the shadows of contemporary life, where the line between good and evil no longer exists.

Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror 2024

, edited and translated by Xueting Christine Ni (Solaris, September 24)

Sinophagia: A Celebration of Chinese Horror 2024

, edited and translated by Xueting Christine Ni (Solaris, September 24)Fourteen dazzling horror stories delve deep into the psyche of modern China in this new anthology curated by acclaimed writer and essayist Xueting C. Ni, editor and translator of the British Fantasy Award-winning Sinopticon. From the menacing vision of a red umbrella, to the ominous atmosphere of the Laughing Mountain; from the waking dream of virtual working to the sinister games of the locked room… this is a fascinating insight into the spine-chilling voices working within China today – a long way from the traditional expectations of hopping vampires and hanging ghosts. This ground-breaking collection features both well-known names and bold upcoming writers, including: Hong Niangzi, Fan Zhou, Chu Xidao, She Cong Ge, Chuan Ge, Goodnight, Xiaoqing, Zhou Dedong, Nanpai Sanshu, Yimei Tangguo, Chi Hui, Zhou Haohui, Su Min, Cai Jun, and Gu Shi.

August 4, 2024

Out This Month: August

The Full Moon Coffee Shop by Mai Mochizuki, translated from the Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood (Ballantine, August 20)

The Full Moon Coffee Shop by Mai Mochizuki, translated from the Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood (Ballantine, August 20)In Japan, cats are a symbol of good luck. As the myth goes, if you are kind to them, they’ll one day return the favor. And if you are kind to the right cat, you might just find yourself invited to a mysterious coffee shop under a glittering Kyoto moon. This particular coffee shop is like no other. It has no fixed location, no fixed hours, and it seemingly appears at random. It’s also run by talking cats. While customers at the Full Moon Coffee Shop partake in cakes and coffees and teas, the cats also consult their star charts, offering cryptic wisdom, and letting them know where their lives veered off course. Every person who visits the shop has been feeling more than a little lost. For a down-on-her-luck screenwriter, a romantically stuck movie director, a hopeful hairstylist, and a technologically challenged website designer, the coffee shop’s feline guides will set them back on their fated paths. For there is a very special reason the shop appeared to each of them

August 1, 2024

SFT on the Hugos There Podcast

I had a great time talking about SF in Translation with Seth of the Hugos There Podcast! Listen to hear some recommendations, our thoughts on the field, and my unwavering enthusiasm for my favorite books and stories from around the world.

Listen here.

July 15, 2024

The SFT of Rio Johan

I’ve recently read two excellent, hilarious stories by Indonesian author Rio Johan (listed below). They are part of a larger collection, not yet translated into English, called Genetically Modified Fruit, about a bio-engineering corporation that produces exotic fruits…with some very peculiar consequences (like world-dominating cherries!!). Hopefully, someone will translate and publish this entire collection, if only because Rachel demands it.

Here are the two stories that are already in English:

“Fruit maps,” translated by Lara Norgaard (Asymptote, 2019).

“Mysteries of Visiocherries,” translated by the author (Samovar, 2021).

July 4, 2024

Out This Month: July

“Death Valley” by Junko Mase, translated from the Japanese by Sharni Wilson

“The Lesser Evil (an excerpt)” by C. E. Feiling, translated from the Spanish by Frances Riddle

“The Devil’s Offspring” by Mahmoud Fikry, translated from the Arabic by Emad El-Din Aysha

“You Have to Read This!” by John Ajvide Lindqvist, translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy

Pink Slime by Fernanda Trías, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary (Scribner, July 2)

Pink Slime by Fernanda Trías, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary (Scribner, July 2)In a city ravaged by a mysterious plague, a woman tries to understand why her world is falling apart. An algae bloom has poisoned the previously pristine air that blows in from the sea. Inland, a secretive corporation churns out the only food anyone can afford—a revolting pink paste, made of an unknown substance. In the short, desperate breaks between deadly windstorms, our narrator stubbornly tends to her few remaining relationships: with her difficult but vulnerable mother; with the ex-husband for whom she still harbors feelings; with the boy she nannies, whose parents sent him away even as terrible threats loomed. Yet as conditions outside deteriorate further, her commitment to remaining in place only grows—even if staying means being left behind.

The Dallergut Dream Department Store by Miye Lee, translated from the Korean by Sandy Joosun Lee (Hanover Square Press, July 9)

The Dallergut Dream Department Store by Miye Lee, translated from the Korean by Sandy Joosun Lee (Hanover Square Press, July 9)In a mysterious town hidden in our collective subconscious there’s a department store that sells dreams. Day and night, visitors both human and animal shuffle in to purchase their latest adventure. Each floor specializes in a specific type of dream: childhood memories, food dreams, ice skating, dreams of stardom. Flying dreams are almost always sold out. Some seek dreams of loved ones who have died. For Penny, an enthusiastic new hire, working at Dallergut is the opportunity of a lifetime. As she uncovers the workings of this whimsical world, she bonds with a cast of unforgettable characters, including Dallergut, the flamboyant and wise owner, Babynap Rockabye, a famous dream designer, Maxim, a nightmare producer, and the many customers who dream to heal, dream to grow, and dream to flourish.

The Black Orb by Kim Ewhan, Sean Lin Halbert (Profile, July 31)

The Black Orb by Kim Ewhan, Sean Lin Halbert (Profile, July 31)One evening in downtown Seoul, Jeong-su is smoking a cigarette outside when he sees something impossible: a huge black orb appears out of nowhere and sucks his neighbour inside.The orb soon begins consuming other people and no one knows how to stop it. Impervious to bullets and tanks, the orb splits and multiplies, chasing the hapless residents of Seoul out into the country and sparking a global crisis with widespread violence and looting. Jeong-su must rely upon his wits as he makes the arduous journey in search of his elderly parents. But the strangest phases of this ever-expanding disaster are yet to come and Jeong-su will be forced to question everything he has taken for granted.

June 7, 2024

Review: The Man Who Spoke Snakish by Andrus Kivirähk

translated by Christopher Moseley

original publication (in Estonian): 2007

this edition (in English): Black Cat, 2015

442 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

First, I’d like to dwell on the fact that this is the first novel translated from the Estonian that I’ve ever read. For those of you who don’t follow me on twitter (@Rcordas), not many things excite me as much as getting my hands on a work of translation from an underrepresented language. For instance, I read two collections of Vietnamese fiction this year, which was very exciting. Reading SFT from these languages makes me feel like I’m slowly but surely expanding my understanding of the richness and variety of thought and art that makes this planet so fascinating.

But back to The Man Who Spoke Snakish. Set in the forests and villages of twelfth-century Estonia, just as Christianity was spreading throughout the country, Kivirähk’s novel focuses on the tragic life of a pagan named Leemet, who is destined to be the last of his kind. As Peter Blackstock, the editor of the translation, has said of the novel, “at its heart it is perhaps a Bildungsroman of a boy whose Bildung ends up being useless when the society around him changes so dramatically it leaves him completely behind. In this way, it’s a book about war, violence, and occupation, as well as magic and tradition. But although there is much in the novel that explores ideas about modernity and existential questions of change, the book surprises with its tone of lightheartedness, of humor.”

Though born in a village, Leemet moves back to the forest with his mother and sister after his father is killed by a bear (the bear was his mother’s lover). Happy to be back in the forest once more, Leemet’s mother returns her family to its ancient ways, which includes using Snakish to communicate with the snakes and animals. In this way, they can procure meat and stay safe from the encroaching “iron men” (knights) and missionaries, who sometimes venture into the forest. Sadly, though, more and more people are moving out of the forest and into the village, lured by modern technology, Christianity, and a general belief that village life is the future.

As the forest empties of people, Leemet and his family become increasingly isolated. Intrigued by the village but suspicious, as well, and disgusted by its foul-tasting bread and silly-looking farming contraptions, Leemet nonetheless befriends a young village girl, whom he will visit from time to time throughout his life. And yet, Leemet is firmly entrenched in the forest, learning Snakish from his uncle and befriending adders, a pair of primates, and other animals.

As he grows up, Leemet recognizes that the crazed sage of the forest who demands increasingly demented sacrifices to forest sprites is no different than the village elder who insists that everyone in the forest must move to the village and convert to Christianity. Leemet’s life becomes increasingly consumed by violence and tragedy as everyone he loves is killed because of fanaticism, hatred, and bloodlust. Left alone in the forest, the last person who knows Snakish and the ways of the forest, Leemet finally finds the mythical Frog of the North, and spends the last of his days with it.

Beautifully translated by Christopher Moseley, The Man Who Spoke Snakish pulls you in to its unexpected and fascinating story, even as the violence that characterizes its second half is difficult to read at times. Ultimately, I look forward to reading more Estonian fiction in the future.

June 1, 2024

Out This Month: June

“The Reflection of Sand by Tan Gang” by Tan Gang, translated from the Chinese by Emily Jin (Clarkesworld, June 1)

“The Reflection of Sand by Tan Gang” by Tan Gang, translated from the Chinese by Emily Jin (Clarkesworld, June 1)

Wafers by Ha Seong-nan, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (Open Letter, June 4)

This 2006 collection of short stories is in line with the unsettling, engrossing style of Ha’s other two collections that have been translated into English, the critical and commercial successes Flowers of Mold and Bluebeard’s First Wife. A best-seller in Korea, Ha Seong-nan is one of the stars of contemporary short fiction, writing edgy, socially conscious stories that bring to mind the novels of Han Kang and the film Parasite.

Under the Neomoon by Wolfgang Hilbig, translated from the German by Isabel Fargo Cole (Two Lines Press, June 11)

Under the Neomoon by Wolfgang Hilbig, translated from the German by Isabel Fargo Cole (Two Lines Press, June 11)An electric collection that evokes the works of Andrei Tarkovsky and Ingeborg Bachmann, Under the Neomoon is a neon-bright reminder of humanity’s violent folly and the importance of storytelling from down below, from the wage worker’s hovel. An abandoned construction site. Glowering pits and furnaces. A lone man in a bungalow. Widely considered to be one of the great German writers of the twentieth century, Wolfgang Hilbig’s dark visions have long held readers aloft with their musical language and uncompromising vision of the modern world. In Under the Neomoon, his debut short story collection originally published in East Germany in 1982, Hilbig’s persistent fixations—factory pits, rampant nature, and split identities—are at their most visceral and brilliant.

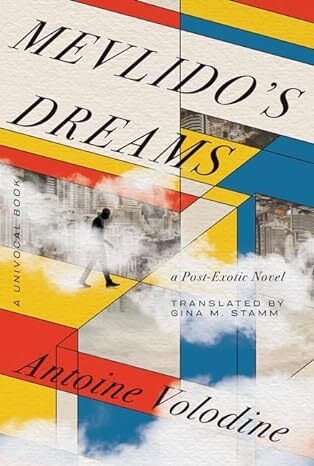

Mevlido’s Dreams: A Post-Exotic Novel by Antoine Volodine, translated from the French by Gina M. Stamm (University of Minnesota Press, June 25)

Mevlido’s Dreams: A Post-Exotic Novel by Antoine Volodine, translated from the French by Gina M. Stamm (University of Minnesota Press, June 25)A meditative, postapocalyptic noir, Mevlido’s Dreams is an urgent communiqué from a far-future reality of irreversible environmental damage and civilizational collapse. Mevlido is a double agent working for the police and living in the last habitable city on the planet, a sprawling abyssal ruin marked by war and ruled by criminals. Suspended in the bardo between his loyalty to the surveillance state and to the anarchists, communists, and other rebels he monitors, Mevlido clings to life and hope—barely—in the city’s vast slums, haunted by the memory of the wife he failed to save during the last war and dreaming of a mysterious mission he is told he must accomplish. At the same time, an enigmatic organization existing elsewhere—the Organs—observes Mevlido’s actions and debates its responsibility to him and to humanity as a whole

May 27, 2024

Review: The Singularity by Dino Buzzati

translated by Anne Milano Appel

original publication (in Italian): 1960

first English edition: 1962, Secker & Warburg (titled Larger Than Life)

this edition: 2024, NYRB Classics

136 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

*spoilers*

Not until a third of the way through this short, dark, mysterious novel do we get even a hint at what the strange government-run installation in the mountains is actually for. Even without knowing where he is going and why, Professor Ermanno Ismani willingly (if uncertainly) embarks on what will be a two-year scientific project. The Ministry of Defense has only said that the installation is crucial for the country and that he, as a professor of electronics, is duty-bound to lend his skills to the project.

When Ismani and his wife Elisa arrive at the mysterious site in the mountains, even the guards don’t know exactly what it’s for. Only when Ismani talks to the other scientists there (and there are only a few- Endriade, Strobele and his wife Olga, Manunta), does he begin to see that this sprawling endeavor is related to artificial intelligence. As Strobele (still only partially) explains, “[W]hat you are looking at is a kind of citadel…[a] little kingdom, hermetically closed off and apart from the rest of the world…to put it simply, this gigantic installation that so far has cost well over ten years of effort is…it’s related to us, it’s a human…A machine made in our likeness” (52).

Each day, a series of strange hums, clicks, sighs, crackles, and even a voice that isn’t quite a voice, floats over the installation, though only certain people can hear it. Endriade, who built it with the help of a brilliant scientist named Aloisi (who commits suicide before Ismani arrives), is able to work out a way to translate the various electrical impulses into intelligible speech. As he explains to Ismani and Elisa, the scientists didn’t give the installation language because it is a “trap for the mind,” and they wanted the artificial intelligence to grow far beyond human consciousness and intellectual abilities.

The scientists’ goal isn’t very clear–just a grand vision of intellectual evolution that will outstrip humanity and…do what? The air of mystery and dread that hangs over the novel from beginning to end makes the project seem downright sinister and potentially catastrophic.

When Elisa happens to see a photo of her old friend Laura in Endriade’s house, the latter winds up spilling the entire genesis of the project and his strange role in it. Laura had been Endriade’s wife, and despite her constant cheating and lying, Endriade had been deeply in love and even obsessed with her. After her fatal car accident a decade before, Endriade’s colleague Aloisi had come to ask him to work on a new kind of artificial intelligence. Still obsessed with Laura, Endriade was somehow able to resurrect her soul/personality/consciousness in the massive machine that they ultimately built within a cavern in the mountains. Buzzati keeps the explanation as to exactly how this was done very nebulous.

Somehow, Laura’s ebullient, joyous personality comes through in the atmosphere surrounding the installation, but it soon turns ugly when what Endriade had feared actually happens. One afternoon, Strobele’s wife, Olga, goes for a swim in a nearby lake and winds up parading her naked body in front of the walls of the installation, hoping to see what the artificial intelligence will do. She quickly realizes her mistake when a robotic arm shoots out from a section of the wall and tries to grab her (it ultimately grabs a passing rabbit and squeezes it to death).

What Endriade had feared–that Laura will remember what she was before, fully realize her new state as a static machine, and become enraged–is exactly what happens. The atmosphere changes–moans, cries, and whines fill the air of the mountains. Wishing to die, Laura then lures Elisa into her corridors and kills her, hoping that this will mean that the scientists shut her down permanently.

One might assume that Buzzati was using the story of the 14th century Italian poet Petrarch and his great love Laura as a basis for exploring the lengths that one might go for love. While Petrarch wrote immortal poetry for a woman he could never have, Endriade attempts to resurrect his own Laura and endow her with powers that no human could ever have. And yet, Laura’s self-consciousness and rage at being the only one of her kind and unable to experience human sensations ever again brings to mind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as well.

Beautifully translated by Anne Milano Appel and a fascinating exploration of hubris and obsession, The Singularity is a must-read as we continue, in the 21st century, to strive for ever-more aware artificial intelligence and learn, at the same time, that we must tread carefully.