Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 2

August 14, 2025

Review: On the Calculation of Volume II by Solvej Balle

translated by Barbara Haveland

original publication (in Danish): 2020

first English edition: 2024, New Directions

185 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

We left Tara Selter at the end of Book I attempting to figure out how to move forward, despite being trapped in November 18 (or maybe it’s everyone else who’s trapped, and only she is moving forward?). Her husband had told her that she needed to go to Paris herself to see if she could jump back into Time–he couldn’t help her. Despite Tara’s year coming full circle, November 18 continues to be November 18 every time she wakes up, so Tara needs to find some other way to give meaning to what has been happening to her.

Book II is a fantastical travelogue, of sorts, in which Tara travels around Europe trying to construct a year out of “fragments.” She visits her parents during what, for Tara, is Christmas (though for them, of course, it’s only November 18). After explaining to them and her sister that she has been trapped in time, Tara convinces them to celebrate an early Christmas, complete with a Christmas pudding and a Bûche de Noël. The family has a pleasant Christmas dinner, but of course everything (except Tara’s memory of it and some food she has kept by her bedside) is erased with the rising of the sun. As she did with her husband Thomas, Tara leaves her parents’ house sadly, quietly, knowing that they will have no memory that she had stopped there at all.

Tara travels for most of this novel, overhearing passengers on trains telling their stories to one another, talking on the phone, discussing their most personal problems. Still, Tara is outside of it all. As she tries to explain to her father, what is happening to her is like “a sort of interweaving of the two times,” in which she can consume things that subsequently disappear from the world. At times, Tara sees herself as a consuming “monster,” one that invisibly dips into the world and takes things that won’t be replaced, without anyone knowing. Thus, she sticks to buying food that will be thrown out or that is in such abundance that its absence won’t be noticed.

Traveling up north in search of winter, Tara encounters a meteorologist, who discusses with her what it really means to follow the seasons. At one point, they talk about how people seem to demand certain things of seasons, like snow in winter or rain in spring, and then become disgruntled if the season is warmer or colder than usual, as if it isn’t playing by the rules. This discussion is just one of the points in the novel that makes us stop and consider Time itself–how we break it up and compartmentalize it in order to make sense of the passing of the year. The weather changes, food and clothing change, but humans call these shifts “summer” or “winter” so as to prepare for these changes and make them more understandable.

While traveling in search of the season corresponding to her own movement through time, Tara keeps two notebooks: one tracking the places she’s visited corresponding to the season she is seeking, and the one that we are reading. At times, Tara mentions what she has written in her seasons notebook, but we can never read it. This is fitting, since that notebook disappears halfway through the book, stolen by what Tara suspects is a soccer fan in town for a big match. And just like that, Tara drops her search for seasons, having moved through an entire year with nothing to show for it. And she had been so optimistic: “If I want seasons, I will have to build them myself. If I am to have a future, I will have to build it myself. I put the pieces together, little fragments of season and I write it all down in my manual: the ingredients of the seasons” (82).

What emerges in this book and its predecessor, one realizes, is an attempt to define Time’s shape. Is it like a river, and Tara is stuck on a shoal? Is it a construction that we are subconsciously always building to give meaning to our lives? Later on, Tara compares it to a container, one that we fill with meaningful moments. It’s almost as if Balle’s novel is a series of attempts to solve a Rubik’s cube, but the cube is Time and we are Balle’s rapt audience, having never thought of making the moves that she is attempting.

Time, Tara sees, is that compressed moment when the woman driving her on a snow-covered winding road to a guest house nearly collides with an oncoming truck. Everything happens in a couple of seconds, but the entire incident seems stretched out.

Time, Tara realizes, is that stream that keeps moving after someone has died. Wandering around the graveyard of an old church, she reads the birth and death dates on the stones, thinking that she nearly joined the dead just the day before on that winding road.

Constructing the seasons, as Tara does, means that she has to live purposefully, sniffing the air for the shift in seasons that only she could detect in that undercurrent of time that her own body is riding (since her hair is still growing, for example, and any injuries she sustains eventually heal). She has to look for appropriate foods for the appropriate season, which forces her to wander from France to Scandinavia, back south to Germany and then Spain. She switches from wool to light jackets, and from boots to sandals, and back again. But then, as mentioned before, her seasons book disappears and she is left, once again, to try and find her way to November 19.

On the 701st November 18, Tara writes, “I have no seasons and I am not scouting for locations for a film. Seasons are not scenes and locations. And you cannot construct a year out of fragments of November. Of course you can’t” (137). Just a few pages before, she had been trying to hard to do just that, but the disappearance of the book reinforces for her the absolute absurdity of what is happening to her. She can’t get out of November 18 and doesn’t know what to try next. Chasing the seasons had given her purpose and may have offered one potential way to move forward in a new current. This has failed, but a new way of finding purpose occurs to Tara after she has settled into a life in Düsseldorf.

The Roman coin that had featured in the first book, and which Tara had been carrying throughout her travels, reappears near the end of the second volume. Tara happens to pull it out of her bag and has a strange reaction to it. Something about the coin, which features Antoninus Pius (a Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161) on one side and the Roman goddess Annona with a grain measure and ears of corn on the other, sets Tara to thinking about the movement of objects through time and history itself.

Tara calls it “a historic object, an emblem from the past, a baton passed down through the centuries, a metallic witness to bygone ages or whatever” (153). But then she spends time looking at it, thinking about it, connecting it to her own time as an antiquarian book dealer, in which she had thought that she was interested in historical objects for the history, but realizes, now, that she loved those objects for their materiality–the way they felt and looked. She thinks about how we invest objects with meaning, and, most importantly for the purposes of this novel, how some objects, like the coin, “had dropped out of history” (158). Is this what has happened to Tara?

This, then, is Tara’s new purpose: she dives into Roman history, taking out books, buying a laptop and doing research on the internet, taking notes, doing everything she can to learn about the conditions that produced that coin. This new purpose takes up her waking hours, and though everything she types and saves on her computer vanishes the next day, still she does her research, using her mind and printed-out sheets of paper that she keeps near her to track her knowledge. And then, while slipping into lectures on Roman history at the university, she discovers something that she hadn’t considered possible–there are others like her, trying to find their way back into Time.

In a way, Solvej Balle has written a Last Man/Woman narrative, but with a twist. Unlike in Guido Morselli’s Dissipatio H. G. or Manon Steffan Ros’s The Blue Book of Nebo, for instance, in which an individual or family finds that they are the only ones left around (as far as they can tell) after an unspecified disaster, Balle’s Tara is surrounded by people everywhere she goes. She interacts with them, but she retains her memories while everyone else resets with the rising of the sun. She is alone but not alone. And yet, there are those other people who are also trying to find their way out of November 18…

Books III and IV will be out in English this November.

August 2, 2025

Out This Month: August

“Sea of Fertility” by Bella Han, translated from the Chinese by the author (Clarkesworld, August 1)

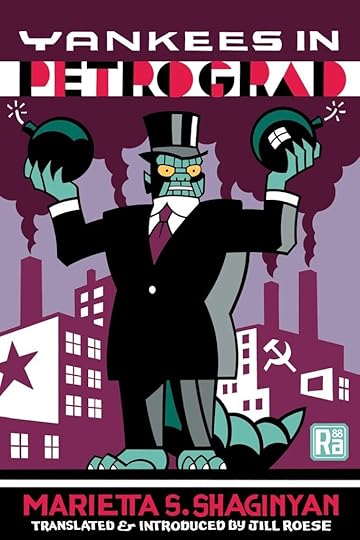

“Sea of Fertility” by Bella Han, translated from the Chinese by the author (Clarkesworld, August 1) Yankees in Petrograd by Marietta S. Shaginyan, translated from the Russian by Jill Roese (MIT Press, August 19)

Yankees in Petrograd by Marietta S. Shaginyan, translated from the Russian by Jill Roese (MIT Press, August 19)When a capitalist cabal plots to assassinate Lenin, can quick-witted American workers ride to the rescue before it’s too late?—a new translation. In Yankees in Petrograd, the Russian author Marietta S. Shaginyan (writing under the American nom de plume Jim Dollar) gives us a riveting crime and espionage adventure with science fiction elements. Despite having awesome technologies such as public transportation that bends space and time and electrical forcefields protecting Soviet Russia against its foes, the world’s first proletarian state is threatened by a fascist organization that will stop at nothing—including kidnapping, mesmerism, and infiltration—to assassinate Vladimir Lenin and his fellow Communist leaders! Enter Mike Thingsmaster, American tradesman and leader of a secret global organization defending the interests of the proletariat, who tasks his network with foiling this nefarious plot.

July 20, 2025

Review: On the Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle

translated by Barbara Haveland

original publication (in Danish): 2020

first English edition: 2024, New Directions

160 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

Longlisted for the 2024 National Book Award for Translated Literature, On the Calculation of Volume I is a book in which so much, and so little, happens. As Balle notes in an interview with the editors of Words Without Borders, the idea for a novel about a woman stuck in a single day came to her around the same time the film Groundhog Day was released, though she didn’t see it until later. Her exploration, of course, goes much deeper than the film, the latter only briefly touching on the philosophical implications of being stuck in a single day. Balle, though, plumbs the depths of what might actually happen if a woman found that time moved differently for her than it does for other people.

Tara Selter spends most of the novel, which is made up of her notes about each November 18 that passes, trying to understand what has happened to her. November 18 seemed like a perfectly normal day–she had traveled to Paris to purchase some books that she and her husband had promised clients through their antiquarian book business. Nothing strange happened–Tara attended an auction, bought a few books, visited her husband’s friend Philip, had tea with Philip and his girlfriend in their shop, burned her hand on their stove, and then traveled back home to Clairon-sous-Bois. The next day, Tara notices that things seem to be repeating themselves, and then she sees that the newspapers, tv stations, and calendars all claim that it is November 18. For Tara, it is November 19.

Naturally, she tries to explain what happened to her husband, who is sympathetic but unsure of what to do. Tara spends months trying to think through what happened to her and living the same day over and over. Each morning, she has to explain to her husband why she is back home early and they investigate various theories proposed by physics as to how someone can become trapped in time. Eventually, Tara gives up this lifestyle and moves to the spare bedroom, leaving her husband to go about his November 18 as it was supposed to be, with Tara in Paris and him waiting for her to come home.

Once the full implication of what has happened to her sinks in, Tara tries to understand what it could signify: “[t]hat time stands still. That gravity is suspended. That the logic of the world and the laws of nature break down. That we are forced to acknowledge that our expectations about the constancy of the world are on shaky ground. There are no guarantees and behind all that we ordinarily regard as certain lie improbable exceptions, sudden cracks and inconceivable breaches of the usual laws” (32).

Eventually, Tara moves out of the house completely, taking up residence down the road, making sure to avoid her husband on his daily walk. She realizes that while some things she buys return to their shelves in the store once the “next” day comes, other things remain. Anything she consumes stays where it is, so her books and papers don’t disappear. Anything she eats remains eaten, and she discovers that they then disappear from the store forever. This realization prompts her to go farther afield in her shopping, trying to find the most unusual and unpopular food so that she isn’t taking away from anyone else.

A coin she bought from Philip and Marie returned to its place in Philip’s shop once November 18 repeated itself, and Tara finds it when she travels back to Paris near the anniversary of the incident. Though Tara doesn’t seem to consider it, it might be this coin (and the other two she looks at) that hold a clue to what happened to her. The coin is an ancient Roman sestertius (“two and one-half”), and next to it are “a silver coin bearing the images of Castor and Pollux” and “a copper denar showing the Lighthouse of Alexandria” (143). The sestertius was only issued rarely, but was struck for over 250 years. The Castor and Pollux coin is particularly interesting because, according to Greek and Roman mythology, these were twin brothers, sons of Leda, with one the son of the mortal Tyndareus and the other the son of Zeus. They took care of shipwrecked sailors and sent favorable winds. The Lighthouse of Alexandria was built in ancient Egypt in order to guide ships safely into harbor.

The symbolism of these coins is hard to ignore. Tara feels shipwrecked in time, having run aground on November 18, recognizing that time is functioning differently for her and everyone else. Indeed, as time moves forward for her (the burn she received heals as if she were moving normally through time), she gets the sense every now and then that a different time is moving beneath the one she is experiencing. The 325th November 18th brings her a feeling of October, as if time had been split in two.

Tara returns to Paris for the anniversary of November 18, hoping that everything will return to normal. When it doesn’t, she considers what to do next and how to live in a way that will allow her to move forward without consuming too much. She knows that her husband can’t help her, so she needs to strike out on her own.

Tara’s story is beautifully rendered in English by Barbara Haveland, who, according to that Words Without Borders interview, enjoyed translating Balle’s other novels and was intrigued by the idea of On the Calculation of Volume. As Haveland says, “[t]ranslating Solvej Balle’s work is a rare treat. Her writing is spare and taut. There is nothing superfluous here, nothing random. Every word is weighed, every phrase and sentence finely honed.” One can see this clearly in On the Calculation of Volume I, and, thankfully, we have six more books in the series to enjoy.

Volume II is out in English now. Volumes III and IV will be out in English this November.

July 18, 2025

Jaroslav Olša, Jr. at SF Ruminations

Check out Joachim Boaz’s interview with Czech diplomat, author, editor, and translator Jaroslav Olša, Jr. on Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations. Olša discusses his book about Czech/American science fiction author Miles (Miroslav) J. Breuer, a regular in the pages of Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing.

July 10, 2025

SFT Week at Strange Horizons

Strange Horizons is focusing on SF in translation this week, with a podcast episode of Critical Friends featuring Dan Hartland, Will McMahon, and myself; as well five SFT reviews. Check it out!

July 4, 2025

Out This Month: July

“Serpent Carriers” by K.A. Teryna, translated from the Russian by Alex Shvartsman (Clarkesworld, July 1)

“Serpent Carriers” by K.A. Teryna, translated from the Russian by Alex Shvartsman (Clarkesworld, July 1)

Into the Sun by C. F. Ramuz, translated from the French (Switzerland) by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan (New Directions, July 1)

It’s been a hot summer for a Swiss lakeside town—both bucolic and citylike, old-fashioned and up-to-date—when a “great message,” telegraphed from one continent to another, announces an “accident in the gravitational system.” Something has gone wrong with the axis of the Earth that will send our planet plunging into the sun: it’s the end of the world, though one hardly notices it, yet … “Thus all life will come to an end. The heat will rise. It will be excruciating for all living things … And yet nothing is visible for the moment.” For now the surface of the lake is as calm as can be, and the wine har vest promises to be sweet. Most flowers, however, have died. The stars grow bigger, and the sun turns from orange-red to red, and then to black-red. First comes denial: “The news is from America, you know what that means.” Then come first farewells: counting and naming beloved things—the rectangular meadows, the grapes on the vines, the lake. In its beauty the world is saying, “Look at me,” before it ends.

June 27, 2025

Review: Red Sword by Bora Chung

Check out my review of Bora Chung’s first novel in English, translated by Anton Hur, in the latest issue of World Literature Today.

“Based on the story of seventeenth-century Korean soldiers fighting against Russia on behalf of the Qing dynasty, Red Sword is a story about war, though here it is the far future, where a vast Empire roams the galaxy finding civilizations from which it can extract resources and technology.…”

June 21, 2025

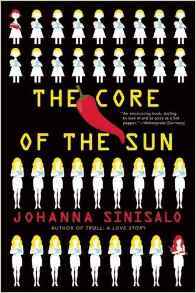

Review: The Core of the Sun by Johanna Sinisalo

translated by Lola Rogers

original publication (in Finnish): 2013

first English edition: 2016, Black Cat

304 pages

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

(warning: spoilers in the last two paragraphs)

Over a decade ago, Johanna Sinisalo’s name was everywhere in the Anglophone sf world. The so-called “Queen of Finnish Weird,” whose deep interest in plants, myth, and the natural world inform her stories, was instrumental in introducing Finnish speculative fiction to Anglophone audiences. Sinisalo edited The Dedalus Book of Finnish Fantasy (2006), co-edied Giants at the End of the World (2017) with Toni Jerrman for Worldcon 75 in Helsinki, and wrote introductions and other pieces for online magazines about the Finnish fantasy, science fiction, magical realism, and surrealism available in English. Somehow, her most famous novel in English, The Core of the Sun, stayed in my TBR pile and only made it to the top now, but better late than never.

The Core of the Sun, so-named for a hallucinogenic chili pepper that may have more wide-ranging powers, is the story of one woman trying to survive in a repressive society while looking for her missing sister and pursuing her addiction to chili peppers. Vera and her sister Mira moved to Finland from Spain to live with their grandmother following their parents’ deaths. Once settled at their grandmother’s farmhouse, they learn that they are to be raised in accordance with Finnish social norms, within the bounds of the country’s eusistocratic society (“reign of health”). Specifically, most girls are raised as “elois”–submissive and stereotypically female–while most boys are raised as “mascos”–dominant and stereotypically male. The first half of the book pieces together how and why Finland adopted this social arrangement, in large part to reign in sections of society that were spinning out of control because of falling marriage rates and growing rifts between the sexes. Finland adopted this method of breeding for certain gender traits from early-20th-century experiments with wolves.

Of course, not everyone fits neatly into these gender roles. Those girls who are clearly independent, dominant, and focused are classified as “morlocks” and pushed to the margins of society, often winding up in orphanages, while boys who clearly aren’t “mascos” have much the same fate. Though Vera and Mira have their names changed to Vanna and Manna (in accordance with eloi rules) and are raised as elois, Vera is clearly not like other girls–she loves reading and learning, hates wearing makeup and high heels, and would rather play with trucks than dolls. Her grandmother recognizes this but comes to an understanding with Vera that she act like her eloi sister so that both can take their places in polite society.

When Manna marries the first man who’s willing (Harri), Vera worries about her sister’s fate but continues at eloi school, wondering what her future will look like as a secret morlock. Vera also knows that something isn’t right about Manna’s marriage, and eventually she stops hearing from Manna altogether. Eventually, Harri is held responsible for Manna’s death but gets a very slight punishment, while Manna’s body is never found. Vera then dedicates her life to finding out what happened to Manna.

Mixed in with excerpts from government documents, educational pamphlets, dictionary entries, and children’s stories from across the decades about elois, gender roles, health, and other relevant topics are Vera’s letters to Manna, detailing what the former’s life has been since her sister disappeared. We learn from these letters that Vera has partnered with Jare, a man who worked on their grandmother’s farm one summer. Together, Vera and Jare sell chili peppers on the black market. Like alcohol, drugs, and caffeine, chili peppers have been banned in Finland because they are seen as disruptive influences. People still crave these stimulants, though, but only chili peppers are still able to get across the border. By accident, Vera discovers that getting a fix with chili peppers helps her get through her depression each day, and with her addiction comes a demand for hotter and hotter chilis.

With Manna missing and Harri out of the picture, Vera and Jare take over Vera’s grandmother’s farm and invite a health cult–the Gaians–to come live and farm on their land. There, Vera, Jare, and the cult members will grow chilis and sell them underground, always aware that the Health Authority is on the lookout for exactly this kind of infraction. The Gaians, though, are not just interested in growing any chili peppers–they are after a legendary pepper that will give its taster supernatural powers. Apparently, the heat of this particular chili is said to give whoever ingests it the ability to exit their body and enter that of other people or animals–a chili they call the Core of the Sun. As one Gaian explains to Vera and Jare, “those who live in the north of Finland…know of methods by which a person can detach from his fragile shell and allow his spirit to move free and unfettered….At high levels, capsaicin produces an invaluable state of receptiveness. It produces tranquillity and sharpens the senses to their maximum sensitivity” (213).

By this point, Vera has stopped writing letters to Manna but saved them to give to her if she ever finds her. Thanks to the Gaians, Jare has saved up enough money to get himself and Vera out of Finland, but before they leave, Vera stops by Manna’s grave to give her the letters and say goodbye. Just days before, Vera had, out of curiosity, sampled a sliver of the Gaians’ latest cultivated pepper and experienced exactly what the Gaians had said about the Core of the Sun. When Harri attacks her at Manna’s grave, Vera uses some chili she has hidden in her bra to incapacitate him. She then ingests another sliver of the Core of the Sun to find Manna by moving her consciousness into the minds of various creatures. Harri had apparently sold Manna to a human trafficker, and Vera uses her powers to transfer Manna’s consciousness (Manna herself is barely alive) to her own mind and keep her there where she is safe. Vera can now go with Jare to a country where they can be free.

Sinisalo patiently builds up this complex world, slowly intertwining gender roles, black market chilis, missing sisters, and health cults, all brilliantly rendered in English by Lola Rogers. Chilis, like men and women, are bred for whatever traits the breeder wishes, and what emerges are extremes–overly-submissive women; powerful, hallucinogenic chilis. Through it all, we stay mostly in Vera’s mind, looking out at the world from her perspective as an outsider who wants her sister back more than anything. Ultimately, it is one chili pepper that helps her.

June 20, 2025

Review: School of Shards by Marina and Sergey Dyachenko

Check out my review of Marina and Sergey Dyachenko’s final installment in the Vita Nostra trilogy–School of Shards–translated by Julia Meitov Hersey, in the latest issue of Words Without Borders.

June 12, 2025

Spotlight: SFT from Small American Publishers

SF in Translation from Small American Publishers of International Literature since 2020

Speculative fiction in translation comes to us each year from a wide array of publishers, many of which are small presses or imprints of larger publishing houses. Eight of these publishers, based in the US and committed to bringing out multiple works of international literature in translation each year, form the backbone of the SFT we enjoy. Deep Vellum, Europa Editions, Graywolf Press, New Directions, Open Letter Books, Restless Books, Two Lines Press, and Wakefield Press have introduced us over the past two decades to highly-acclaimed writers like Yoss (Cuba), Rodrigo Fresan (Argentina), Yoko Tawada (Japan/Germany), Giacomo Sartori (Italy), Jean Ray (Belgium), Ha Seong-nan (Korea), and others, broadening our horizons and pushing us to think more critically about what “speculative fiction” means. In these books, we meet conscious AIs, families surviving apocalypse, people trapped in time loops, book censors resisting their mandates, positronic robot detectives, and more, with stories ranging from the gothic and Weird to hard science fiction and the surreal. Since 2020, these publishers have together brought us 56 novels, collections, and anthologies translated from the Arabic, Catalan, Chinese, Danish, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Sierra Zapotec, Spanish, Swahili, Swedish, and Welsh. These small publishers play a crucial role in continuing to supply American readers with stories that showcase the richness and diversity of our world.

(in order of publication date)

2020

Beautiful by Massimo Cuomo, translated from the Italian by Will Schutt (Europa Editions).

That We May Live: Speculative Chinese Fiction, edited by Dorothy Tse, et. al., translated from the Chinese (China, Taiwan) by various translators (Two Lines Press).

Girls Lost by Jessica Schiefauer, translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel (Deep Vellum).

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor, translated from the Spanish (Mexico) by Sophie Hughes (New Directions).

A Strange Country by Muriel Barbery, translated from the French (France) by Allison Anderson (Europa Editions).

The Great Nocturnal by Jean Ray, translated from the French (Belgium) by Scott Nicolay (Wakefield Press).

Red Dust by Yoss, translated from the Spanish (Cuba) by David Frye (Restless Books).

Spiral (#3) by Agustin de Rojas, translated from the Spanish (Cuba) by Nick Caistor and Hebe Powell (Restless Books).

The Journey by Miguel Collazo, translated from the Spanish (Cuba) by David Frye (Restless Books).

Waystations of the Deep Night by Marcel Brion, translated from the French (France) by George MacLennan and Edward Gauvin (Wakefield Press).

Red Ants by Pergentino José, translated from the Sierra Zapotec (Mexico) by Thomas Bunstead (Deep Vellum).

The Clerk by Guillermo Saccomanno, translated from the Spanish (Argentina) byAndrea G. Labinger (Open Letter).

The Hole by Hiroko Oyamada, translated from the Japanese by David Boyd (New Directions).

Harmada by João Gilberto Noll, translated from the Portuguese (Brazil) by Edgar Garbelotto (Two Lines Press).

Circles of Dread by Jean Ray, translated from the French (Belgium) by Scott Nicolay (Wakefield Press).

2021

Bug by Giacomo Sartori, translated from the Italian by Frederika Randall (Restless Books).

Eleven Sooty Dreams by Manuela Draeger, translated from the French (France) by J. T. Mahany (Open Letter).

Rabbit Island by Elvira Navarro, translated from the Spanish (Spain) by Christina MacSweeney (Two Lines Press).

Slipping by Mohamed Kheir, translated from the Arabic (Egypt) by Robin Moger (Two Lines Press).

Little Bird by Claudia Ulloa Donoso, translated from the Spanish (Peru) by Lily Meyer (Deep Vellum).

Stranger to the Moon by Evelio Rosero, translated from the Spanish (Colombia) by Victor Meadowcroft and Anne McLean (New Directions).

Life Sciences by Joy Sorman, translated from the French (France) by Lara Vergnaud (Restless Books).

The Blue Book of Nebo by Manon Steffan Ros, translated from the Welsh by the author (Deep Vellum).

His Name was Death by Rafael Bernal, translated from the Spanish (Mexico) by Kit Schluter (New Directions).

2022

Scattered All Over the Earth by Yoko Tawada, translated Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions).

Black Village by Lutz Bassmann, translated from the French (France) by Jeffrey Zuckerman (Open Letter).

When I Sing, Mountains Dance by Irene Solà, translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem (Graywolf Press).

At the Edge of the Woods by Masatsugu Ono, translated from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter (Two Lines Press).

The Conversation of the Three Wayfarers by Peter Weiss, translated from the German (Germany) by E. B. Garside (New Directions).

The Remembered Part by Rodrigo Fresan, translated from the Spanish (Argentina) by Will Vanderhyden (Open Letter).

3 Streets by Yoko Tawada, translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions).

The Famous Magician by César Aira, translated Spanish (Argentina) by Chris Andrews (New Directions).

Weasels in the Attic by Hiroko Oyamada, translated from the Japanese by David Boyd (New Directions).

The Impersonal Adventure by Marcel Bealu, translated from the French (France) by George MacLennan (Wakefield Press).

2023

Ten Planets by Yuri Herrera, translated from the Spanish (Mexico) by Lisa Dillman (Graywolf Press).

No Edges: Swahili Stories, various authors, various translators (Two Lines Press).

Kappa by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, translated from the Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell (New Directions).

The White City Tale by Choi Jeong-Hwa, translated from the Korean by Janet Hong (Restless Books).

Owlish by Dorothy Tse, translated from the Chinese (China) by Natascha Bruce (Graywolf Press).

The City of Unspeakable Fear by Jean Ray, translated from the French (Belgium) by Scott Nicolay (Wakefield Press).

Fishing for the Little Pike by Juhani Karila, translated from the Finnish by Lola Rogers (Restless Books).

2024

You Glow in the Dark by Liliana Colanzi, translated from the Spanish (Bolivia) by Chris Andrews (New Directions).

Through the Night Like a Snake: Latin American Horror Stories, edited by Sarah Coolidge, various translators from the Spanish (Two Lines Press).

The Book Censor’s Library by Bothayna Al-Essa, translated from the Arabic (Kuwait) by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain (Restless Books).

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, translated from the Spanish (Spain) by Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott (Two Lines Press).

Wafers by Ha Seong-nan, translated from the Korea n by Janet Hong (Open Letter).

Under the Neomoon by Wolfgang Hilbig, translated from the German (Germany) by Isabel Fargo Cole (Two Lines Press).

Festival & Game of the Worlds by César Aira, translated from the Spanish (Argentina) by Katherine Silver (New Directions).

Suggested in the Stars by Yoko Tawada, translated Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions).

On the Calculation of Volume (Books 1 and 2) by Solvej Balle, translated from the Danish by Barbara J. Haveland (New Directions).

The Third Temple by Yishai Sarid, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Restless Books).

2025 (so far)

Adam and Eve in Paradise by José Maria de Eça de Queirós, translated from the Portuguese (Portugal) by Margaret Jull Costa (New Directions).

Ultramarine by Mariette Navarro, translated from the French (France) by Eve Hill-Agnus (Deep Vellum).

Archipelago of the Sun by Yoko Tawada, translated from the Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani (New Directions).

The Fake Muse by Max Besora, translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem (Open Letter).

The Event by Juan José Saer, translated from the Spanish by Helen R. Lane (Open Letter).