Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 4

January 1, 2025

2025

JANUARY

“Beyond Everything” by Wang Yanzhong, translated from the Chinese by Stella Jiayue Zhu (Clarkesworld).

—-. “A Small Extinction, Part 1,” translated by Anton Hur (Words Without Borders).

—-. “A Small Extinction, Part 2,” translated by Anton Hur (Words Without Borders).

FEBRUARY

“Hotel California” by Hsin-Hui Lin, translated from the Chinese (Taiwan) by Ye Odelia Lu (Samovar).

“Bodyhoppers” by Rocío Vega, translated from the Spanish [Spain] by Sue Burke (Clarkesworld).

December 3, 2024

Out This Month: December

“The Coffee Machine” by Celia Corral-Vázquez, translated from the Spanish by Sue Burke (Clarkesworld, December 1)

“Life Sentence” by Gelian, translated from the Chinese by Blake Stone-Banks (Clarkesworld, December 1)

November 2, 2024

Hungarian SFT

Out This Month: November

“Because Flora Had Existed. And I Had Loved Her” by Anna Martino, translated from the Portuguese (Brazil) by the author (Samovar, October 28).

“Whale Ocean” by Nanpai Sanshu, translated from the Chinese by Xueting C. Ni (Samovar, October 28)

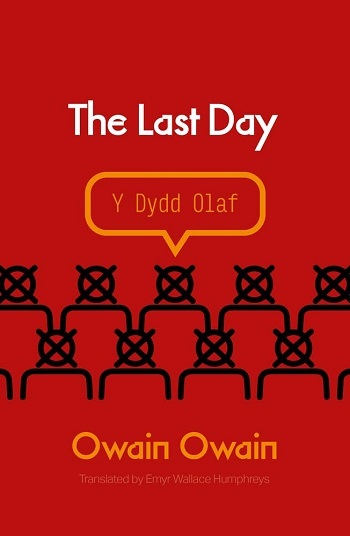

The Last Day by Owain Owain, translated from the Welsh by Emyr Wallace Humphreys (Parthian Books, November 7)

The Last Day is more than a moving call to arms for speakers of minority languages facing extinction; at its core, it’s a tragic human-scale story played out between the few figures who could have stopped the madness before it was too late. It is, moreover, a meditation on themes like free will, artificial intelligence and the socio-historical processes that contribute towards the death of a nation. These themes are as relevant now – if not more so – as they were when the novel was written. With science fiction tropes recalling Philip K. Dick, Kurt Vonnegut and more recently Olga Ravn’s The Employees, philosophical reflections in the vein of Dostoyevsky’s Notes From the Underground, and its postmodern form, The Last Day is a testament to the depth and creativity of Welsh literature. Its translation into English is long overdue.

On the Calculation of Volume (Book I) by Solvej Balle, translated from the Danish by Barbara J. Haveland (New Directions, November 18)

On the Calculation of Volume (Book I) by Solvej Balle, translated from the Danish by Barbara J. Haveland (New Directions, November 18)LONGLISTED FOR THE 2024 NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FOR TRANSLATED LITERATURE

Tara Selter has involuntarily stepped off the train of time: in her world, November 18th repeats itself endlessly. We meet Tara on her 122nd November 18th: she no longer experiences the changes of days, weeks, months, or seasons. She finds herself in a lonely new reality without being able to explain why: how is it that she wakes every morning into the same day, knowing to the exact second when the blackbird will burst into song and when the rain will begin? Will she ever be able to share her new life with her beloved and now chronically befuddled husband? And on top of her profound isolation and confusion, Tara takes in with pain how slight a difference she makes in the world. (As she puts it: “That’s how little the activities of one person matter on the 18th of November.”)

On the Calculation of Volume (Book II) by Solvej Balle, translated from the Danish by Barbara J. Haveland (New Directions, November 18)

The first year of November 18th has come to a close: on its 368th iteration, Tara Selter has returned to her hotel room in Paris, the place where her time problem began. As if perched at the edge of a precipice, she readies herself to leap into November 19th. Book II of Solvej Balle’s astounding seven-part series On the Calculation of Volume beautifully expands on the speculative premise of Book I, drawing us further into the maze of time, where space yawns open, as if suddenly gaining a new dimension, extending into ever more fined-grained textures. Within this new reality, our senses and the tactility of things grow heightened: sounds, smells, sights, objects come suddenly alive, as if the world has begun whispering to us in a new language.

The Third Temple by Yishai Sarid, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Restless Books, November 26)

The Third Temple by Yishai Sarid, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan (Restless Books, November 26)In a near-future Jerusalem, harrowing omens plague the city: a desecrated altar, an unbearable stench, a rampant famine. Shaken but devout, Jonathan, the royal family’s third son, continues to hold services and offer animal sacrifices at the prophesied Third Temple, built to consecrate the founding of the new Kingdom of Judah. His father, Israel’s self-appointed king, has abolished the Supreme Court. The Torah is the law of the land, and only people of the Jewish faith are allowed in. When war breaks out and an angel of God begins to torment Jonathan, warning him of his father’s sacrilege, the foundations of the young priest’s faith—and then his world—begin to give way.

October 31, 2024

Hungarian SFT: An Overview

Hungarian speculative fiction in English translation has been around since the early twentieth century, with more than thirty novels, collections, and stand-alone stories. From the Gulliver’s Travels-inspired stories of Frigyes Karinthy to the Kafkaesque absurdity of Ferenc Karinthy, and from the hard science fiction of Péter Zsoldos and Botond Markovics to the horror of Atilla Veres, there’s something for every reader to enjoy!

Essays on Hungarian Speculative Fiction- Written for this Feature

“Translating (SF) from Hungarian” by Peter Sherwood

“Hungarian Speculative Fiction: The Three Pillars” by Austin Wagner

Other Essays on Hungarian Speculative Fiction

“The Hungarian Way of Science Fiction” (SFRA Review)

“Hungary” (Encyclopedia of Science Fiction)

“Hungarian Speculative Fiction: Forceful, Vicious, Viscous” (Hungarian Literature Online)

“The Kaleidoscope Of Hungarian Fantastic Literature In The 21st Century” (Sci Phi Journal)

NOVELS

1916 / tr 1966

1916 / tr 1966

1941 / tr 1975

1941 / tr 1975

1983 / tr 1984

1983 / tr 1984

1970 / tr 2008

1970 / tr 2008

2002 / tr 2012

2002 / tr 2012

1992 / tr 2013

1992 / tr 2013

1971 / tr 2018

1971 / tr 2018

2014 / tr 2021

2014 / tr 2021

2011 / tr 2021

2011 / tr 2021

2023

2023

2023

2023

2023

2023

2017 / tr 2023

2017 / tr 2023COLLECTIONS

1904

1904

1916 / tr 1965

1916 / tr 1965

1908 / tr 1980

1908 / tr 1980

2022

2022STAND-ALONE SHORT STORIES

Jokai, Mor. “The Drop of Blood,” unknown translator (The Fifteenth Fontana Book of Great Horror Stories, 1982).

Képes, Gábor. “House on the Edge of the Crater,” translated by Anna Kállai (Samovar, 2024).

Kleinheincz, Csilla. “A Drop of Raspberry,” translated by Noémi Szelényi (Interfictions: An Anthology of Interstitial Writing, 2007).

—-. “After Midnight, Before Dawn,” unknown translator (Black Petals #39, 2007).

—-. “Mermaidsong,” translated by Bogi Takács (Mermaids Monthly, 2021).

—-. “Rabbits,” translated by the author (Expanded Horizons, 2010).

—-. “A Single Year,” translated by the author (The Apex Book of World SF 2, 2012).

Komor, Zoltán. “The System’s Lymph Node,” translated by Austin Wagner (Hungarian Literature Online, 2023).

Lengyel, Peter. “Rising Sun,” translated by Oliver A.I. Botar (The Penguin World Omnibus of Science Fiction, 1986).

Nagy, Lajos Parti. “Oh, Those Chubby Genes,” translated by Judith Sollosy (Words Without Borders, 2010).

Rusvai, Mónika. “Bone by Bone,” translated by Vivien Urban (Samovar, 2024).

Sepsi, László. “Déniel” (excerpt from Fruiting Bodies), translated by Austin Wagner (Hungarian Literature Online, 2022).

Szélesi, Sándor. “Creative Years,” translated by Gergely Kamper (Creatures of Glass and Light, 2007).

—-. “How Long is the Road?” translated by Gergely Kamper (SFRA Review, 2022).

—-. “You Will Go, You Will Return,” unknown translator (The Viral Curtain, 2022).

Veres, Atilla. “Just a Bit Easier,” translated by Austin Wagner (Hungarian Literature Online, 2023).

—-. “The Time Remaining,” translated by Luca Karáfiath (The Valancourt Book of World Horror Stories, Volume One, 2020).

Hungarian SFT: Peter Sherwood on Translating Hungarian SF

“Translating (SF) from Hungarian”

by Peter Sherwood

My first translations from Hungarian appeared in my school’s magazine in the late 1960s and the most recent last month, so I have quite a lot of experience and thus quite a lot to say, about translating from Hungarian into English. And I taught Hungarian at universities in Britain and the US for more than 4o years. So: I’m glad you asked me that… and I hope you won’t regret asking…

Hungarian (Magyar) is spoken by over ten million people in the heart of Europe (and more elsewhere) and is genealogically unrelated to the languages that surround it, being Uralic (an earlier, less accurate term used was Finno-Ugric/Finno-Ugrian) while the neighbouring languages all belong to major branches of Indo-European — the language family to which English also ultimately belongs. The differences are not just in vocabulary — though of course the monosyllables forming Magyar’s core resemble nothing else spoken on the planet — but especially in language type. Magyar is an agglutinating language, which means that it mainly uses straightforwardly segmentable endings on its words to convey its grammar, whereas English, say, typically uses word order. In ‘Jack loves Jill’ it is the fact that Jack is positioned in front of ‘loves’, and Jill after it, that tells us who loves whom. Other sequences of these words are not grammatical, or if they are (as in ‘Jill loves Jack’), they mean something else. In Magyar you must put an ending — actually, rather in the way that the -m is added (or, at least, used to be added) to ‘who’ in ‘whom’ — to indicate who is being loved, which leaves ALL the other possible sequences of the three words grammatically permissible and hence used indicate more delicate variations about the information; to convey these in English would be impossibly clumsy-sounding (‘It is Jill (and not someone else) that Jack loves’; ‘It is Jack (and not someone else) that loves Jill’; ‘It is loving (and not some other activity) that Jack “does” to Jill’; and so forth.) You can immediately see why this can be a big problem for the (literary) translator to convey accurately yet smoothly.

In terms of the other major system in language, that of the verb, Magyar has only two basic tenses, past and non-past, a conditional mood, and several secondary ways of referring to the future, whereas English has — well, lots and lots of regular verbal forms. Compare Magyar with what amounts to ‘I go, I went, I would go’, with this range: ‘I go, I am going, I went, I was going, I did go, I have gone, I have been gone, I had gone, I had been gone, I had been going, I will go, I will be going, I will have gone, I would go, I would be going, I would have gone…’ Enormous care is needed in translating from Hungarian into English in this area especially, and even Hungarian speakers who have spent decades in an English-speaking environment may not be able to render English verbal forms accurately.

One really big difference in language type is that Magyar lacks the notion of gender entirely. It’s not just that it does not classify nouns in terms of masculine or feminine (like French) or masculine, feminine and neuter (like German), or English (which used to be like German). Unlike the three languages mentioned, it actually has only a single word to cover both ‘he’ AND ‘she’. In any case, the six personal endings on the verb forms are generally sufficient, so personal prounouns like ‘I’ and ‘you’ and ‘(s)he’ are not much used. This rarely presents a problem in everyday life, which is never context-free, but in literature, where it is the author who creates the context, it may well. For example, in Noémi Szécsi’s SF novel The Finno-Ugrian Vampire, which the author wrote mainly in Finland while studying Finnish — a language typologically very similar to Magyar in terms of pronoun use — she exploited this feature of the grammar to (try to) prevent the reader from identifying the gender of the eponymous vampire. In fact, in my 2012 translation I found I could avoid using a pronoun much of the time, but on occasion I couldn’t — and then opted for ‘she’. However, my reason for this was that the vampire’s name is Jerne (pronounced almost like ‘Yearner’, one who yearns) and, whether the author (and her Hungarian readership) was aware or not, this is in fact an older Hungarian form of Irene… We had a bit of a tussle over this issue, but ended up on the best of terms and in the end Noémi was happy with my version overall. On the other hand, in Edina Szvoren’s collection Sentences on Wonderment (2024), in the short story “Csemete”, which can mean ‘young plant’ or ‘young child (of either sex)’ or even ‘(youngish) pet’, the story deliberately prevents the reader of the Magyar from identifying the protagonist, so in my co-translation (with Erika Mihálycsa), in order to avoid using ‘he/she/it’, I invented a name for (the) csemete, ‘Spriggie’, which we used whenever a pronoun was demanded by the English. This may be a little clunky in places, but where it is, it does force the reader of the translation to reflect on who or what Spriggie, and Spriggie’s gender, might be in a way analogous to the original.

Moving from a short story to one of the great novels of our time: Ádám Bodor’s extraordinary The Birds of Verhovina, which I translated in 2021, has just been voted the sixth most important Hungarian novel of the twenty-first century, yet his breakthrough The Sinistra Zone failed to attract much attention in English, as Ágnes Orzóy’s masterly analysis of this superficially fluent translation’s delicate but fatal flaws reveals (“Reading Ádám Bodor’s Sinistra körzet [‘The Sinistra Zone’] in English”. Hungarian Cultural Studies, the e-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Vol. 11 (2018), 104-119.) In fact, all Bodor’s work is highly SF-relevant. In terms of location, for example, the place-names — some ‘real’, some invented/borrowed/distorted — suggest the multilingual and multiethnic eastern periphery of Europe (or perhaps it could be called the western periphery of Asia? There is at least one ‘real’ Ver(k)hovina in present-day Ukraine…). The personal names, too, are likewise similarly hard to pin down, certainly deliberately disorienting (diswesterning?). Ultimately, however, as its subtitle (Variations on the End of Days) suggests and like many of the greatest books, Verhovina is about us and about now: one of the most compelling and immersive accounts of decline (moral and physical), environmental degradation, loneliness and geographical isolation that has ever been written. And humorous, too.

I am hoping to translate more of Bodor’s SF soon: a selection of his short stories is — fingers crossed — in the works.

Peter Sherwood

London

10 October 2024

Hungarian SFT: Austin Wagner on Three Hungarian SFF Authors

Hungarian Speculative Fiction: The Three Pillars

by Austin Wagner

When it comes to writing about Hungarian speculative fiction for an English-speaking audience, an enormous problem rears its ugly head before the first sentence can even be typed out – namely that very little speculative fiction written in the last fifty years has been translated from Hungarian into English. You have some classics from the early and mid-20th century that have made it into translation, sure – but just as British fantasy, Polish science fiction, and American horror didn’t start and end with Tolkien, Lem, and Lovecraft, neither did Hungarian speculative fiction die before the turn of the century. If you believe, like I do, that one of the greatest strengths of SFF is to comment on, critique, and question the ills of society, to shine a light (however eldritch) on the plight of those suffering the most, shouldn’t we be fighting tooth and nail to get more contemporary SFF into English? I certainly think so.

So, teeth filed and nails sharpened, I’d like to introduce three Hungarian authors today – not only are they three of my personal favorites, they are also inarguably three of the pillars holding up the world of contemporary Hungarian speculative fiction. And as fate would have it, they each occupy a different corner of the SFF tent: Botond Markovics with science fiction, Anita Moskát with fantasy, and Attila Veres with horror.

SCIENCE FICTION – BOTOND MARKOVICS

In the world of science fiction, Botond Markovics (who previously wrote under the penname Brandon Hackett) will be the first on nearly anyone’s list. Though here it’s especially important to reiterate that we’re looking at contemporary science fiction; there is a strong science fiction tradition in Hungary, but its icons – Péter Zsoldos, István Nemere, or the Galaktika magazine – were mostly in their heyday throughout the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. When it comes to sci-fi that has appeared post-2000, multi-award-winning Markovics is largely unrivaled in consistency and success.

Markovics’ work is in many ways classical space opera. Far future, spacefaring adventure, star-hopping humans (or transhumans), black holes and wormholes, stellar technology, the works. But while the foundational elements of his books may be familiar to the avid sci-fi reader, the skill with which he seamlessly integrates the social concerns of the modern age into his page-turning narratives as they plow relentlessly forward is unparalleled.

This seamless integration is what strikes me most with Markovics’ work. Issues of gender, economic inequality, xenophobia, and corporate or political greed feature frequently in his work, but never in a heavy-handed, overwrought, “look at me I’m talking about current events” way. As a case study, we can look at Markovics’ sole full-length novel available in English, Disposable Bodies. In it, humans develop the technology to print new bodies for themselves as frequently as they wish, transferring their consciousness from body to body. So, naturally, it becomes the norm for people to experiment with different body types, genders, physiques, etc. Whether or not someone truly is male or female ceases to matter – characters who began the book locked into their original gender often spend more time in other bodies than their “own.” Sexual intimacy becomes a marathon affair, with partners swapping out spent bodies for fresh ones, changing gender, build, race, you name it. Is Markovics making some grand statement, pointing a flashing sign at his stance on transgender rights or how gender and sexuality exist on a spectrum? No. This is simply a logical, natural consequence of the world he has created. In his 2017 novel Xeno, we encounter multiple alien races – one is completely genderless, another has a sexual classification system undiscernible to humanity, and the methods and duties associated with reproduction are unlike anything on Earth. Which makes sense! Why would alien species from across the galaxy fall into artificial, human-manufactured categorizations? This fluidity in both Markovics’ thinking, writing, and integration of these ideas into his books in a natural, unobtrusive, but still crucial way, is what makes his writing so compelling for me.

FANTASY – ANITA MOSKÁT

Not to be outdone in matters of social commentary, we turn to fantasy and Anita Moskát. Where Markovics excels in robust, fast-pace storytelling, Moskát thrives on pure creativity and the originality of her ideas. It is no exaggeration to say she is one of, if not the, most original SFF writers in Hungary today. Her standout novel is undoubtedly 2019’s Skin and Hide, a piece of biological and political fantasy as unexpected and gut-wrenching as biology and politics can be in the real world. In it, animals suddenly and unexpectedly begin to cocoon up, only to emerge days later as part-human, part-animal (and derogatorily named) breeds. In some places throughout the world (Denmark, from where one of the characters hails), they are welcomed and integrated, while in others (Budapest, where the story takes place) they are ostracized, controlled, and herded into ghettos. You would be hard put to find a more pointed analogy to the “migration crisis” in Europe beginning in 2015, but I’ll touch on this more later.

Another of Moskát’s brilliantly socially-minded works is Anchorpoint (Horgonyhely), in which humans are tethered to the spot in which they were born, unable to travel more than a thousand or so paces in any direction. The only group that can travel freely, and who have therefore consolidated a great deal of power? Pregnant women. But what is it that gives pregnant women this power? What anchored humans to their birth spots in the first place? How do the earth eaters, humans with the power to consume earth and use its magic to help crops and gardens flourish, factor into this upside-down power dynamic?

What I love most about Moskát’s work is its refusal to oversimplify. In both of the aforementioned books, it would have been incredibly easy to label the “good guys” and the “bad guys” based on current political discourse. In Skin and Hide, she could have made the breeds the perfect victims – wholly innocent, harmless, perfect in their victimhood. But she didn’t. The breeds are just as complex, multifaceted, and often flawed as those wielding power over them. In Anchorpoint, she could have said men are violent and bad, women are innocent and good, end of story. But she didn’t. Some of the women in power are as ruthless and abusive as many of the real world’s powerful, publically outed and disgraced men, while many of the men are subjugated and exploited, treated as second-class citizens at best, slaves at worst. Moskát addresses complex societal issues in a complex manner, refusing to oversimplify these fraught topics, encouraging the reader to think beyond the lightning-fast soundbites we’re accustomed to thinking in nowadays.

HORROR – ATTILA VERES

And finally we turn to Attila Veres, the representative of what happens to be my personal favorite in terms of genre: horror. Of the three authors discussed here, Veres has so far found the most success in the English market: while Markovics has independently published the aforementioned Disposable Bodies available in ebook format, and a Czech translation of Moskát’s Anchorpoint is forthcoming from Host Publishing in Veronika Erdély’s translation, Veres has a proper flesh-and-blood collection of short stories that was released in 2022, The Black Maybe: Liminal Tales, translated by Luca Karafiáth and published by Valancourt Books, and which made it onto 2023’s Bram Stoker Awards short list, which, to anyone who has already picked up the collection, is no surprise. Veres is a master of the short story, and particularly the Hungarian short story. His work, perhaps in more ways than Markovics and Moskát, is truly and distinctly Hungarian, often centering the traditions of rural Hungary, from harvest season to thermal baths to the famous (or infamous) pig slaughter. As I wrote previously in my review of the collection: “In Europe’s Hungary, men rise at dawn, get well and drunk, slaughter a pig, and spend all day butchering, boiling, and otherwise making use of all the animal bits. In Veres’ Hungary, however, the pig is replaced with things far more bizarre, whether it’s recently deceased villagers returning from the grave, or something far more ethereal, more essential, ripped from the interdimensional aether and mixed into the earth for a fruitful harvest.”

While mostly known for his short stories, Veres has also written a full-length novel, Darker Outside. Perhaps not as popular as his shorter works, it is nonetheless a wonderfully original tale. It takes place on a farm (of sorts), placing it well within Veres’ wheelhouse, but is also deeply Lovecraftian – strange tentacled creatures have suddenly appeared in one of Hungary’s forests, and cannot be relocated beyond the country’s borders. But they have their uses, and are therefore protected (exploited?) by workers who extract their bodily byproducts. The main character develops a unique connection with the creatures before being sucked into a nightmarish series of events straight out of the mind of Lovecraft’s and Veres’ love child. Like any of his short stories, it is eldritch, bizarre, rural, surreal, and deeply, horrifyingly Hungarian, which is what keeps me coming back to his work time and again.

AFTERWORD: IMMIGRATION

I have not been entirely forthright with you. Yes, I chose perhaps my three favorite authors to talk about. Yes, they are indeed the undisputed leading figures of their respective genres. But another reason I wanted to write about these three was because of three of their specific works, which I have already alluded to: Botond Markovics’ Xeno, Anita Moskát’s Skin and Hide, and Attila Veres’ Darker Outside. These three books, aside from being outstanding works in their own right, take on a whole new dimension when considered as a set. And that is because of both when and why they were published.

These three books, all published between 2017 and 2019, are a response to the so-called “2015 European migrant crisis,” in which large numbers of migrants and refugees entered Europe – many through Hungary – fleeing war and devastation across Africa and the Middle East. Hungary is sadly, and by now infamously, hostile toward migrants. As such, it is no accident that we now return to my earlier contention that “one of the greatest strengths of SFF is to comment on, critique, and question the ills of society, to shine a light on the plight of those suffering the most.” Because these three novels are stories of immigration, of arrival, of otherness. In Xeno, Earth is colonized, along with two other planets inhabited by different species of aliens, by a technologically superior race, and citizens from the three worlds are forcibly migrated about the galaxy for reasons none of them know. In Skin and Hide, a new group of undesirable breeds appears, and we see how Hungarian society reacts to the newcomers. In Darker Outside, an alien species arrives – or perhaps was always there, unseen – and is at first hunted, later farmed and exploited, a weird and bizarro cattle.

These works all explore the topics of immigration, acceptance, exploitation, bigotry, and fear of the unknown, words we are all too familiar with in today’s political and social discourse. But this is precisely why they are so important. They show the power of speculative fiction to react to social, cultural, and political upheaval, and these authors, these works, show that the Hungarian speculative fiction community, and the literary community at large, is pushing back against the rhetoric for which Hungary is becoming internationally known. If anyone ever asks me what makes Hungarian speculative fiction unique, what sets it apart from the wealth of genre books that are already out there, and why it should be translated into as many languages as possible, these are the books and the authors I point to.

Hungarian SFT: Novels (Part I)

The Nightmare (1916) by Mihály Babits, translated by Eva Racz (Corvina Books, 1966).

“A Nightmare, the English title of what the original translates as The Stork-Caliph in reference to an 1826 German fairy tale in imitation of Arabian Nights-style fables, is a story of psychological fantasy (… it belongs rather to the Decadent tradition of spiritual alienation and aesthetic horror) which any reader of Poe would recognize both for its loose gestural suggestion of place and time and for its minute working out of the “rules” of the break with reality.” – Jonathan Bogart

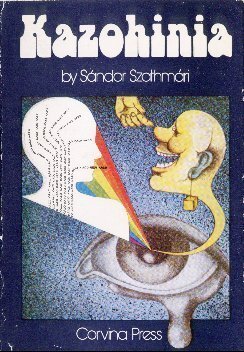

Voyage to Kazohinia (1941) by Sándor Szathmári, translated by Inez Kemenes (Corvina Press, 1975)

“Voyage to Kazohinia is a tour de force of twentieth-century literature–and it is here published in English for the first time outside of Hungary. Sándor Szathmári’s comical novel chronicles the travels of a modern Gulliver on the eve of World War II. A shipwrecked English ship’s surgeon finds himself on an unknown island whose inhabitants, the Hins, live a technologically advanced existence without emotions, desires, arts, money, or politics.”

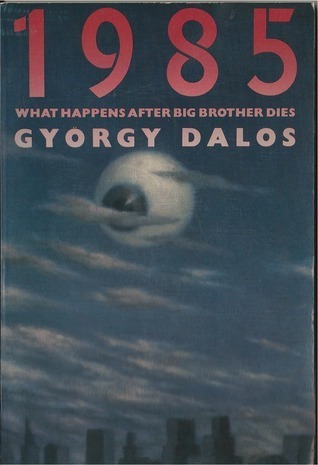

1985: A historical report (Hongkong 2036) from the Hungarian of *** (1983) by György Dalos, translated by Stuart Hood and Estella Schmid (Pantheon Books, 1984)

January 3, 1985. The announcement comes over the telescreen: Big Brother is dead. His empire, Oceania, has been defeated in a disastrous air battle and is no more. Only two great powers remain: Eurasia and Eastasia. Behind the scenes Big Sister (Big Brother’s widow) struggles with the Thought Police and the army for power, while elsewhere the winds of reform sweep through the remnants of Oceania. Everywhere, under the bitingly humorous hand of Gyorgy Dalos, George Orwell’s chilling world of “1984” seems to be experiencing a thaw, as Orwell’s tortured lovers Smith and Julia, O’Brien the Thought Policeman, Ampleforth the hack poet, and Syme the cynical philologist come alive again. However, when the thaw becomes a revolution as the proles get involved, the now-friendly neighboring empire Eurasia steps in to “restore order.”

Metropole (1970) by Ferenc Karinthy, translated by George Szirtes (Telegram Books, 2008)

“A linguist flying to a conference in Helsinki has landed in a strange city where he can’t understand a word anyone says. As one claustrophobic day follows another, he wonders why no one has found him yet, whether his wife has given him up for dead, and how he’ll get by in this society that looks so familiar, yet is so strange. In a vision of hell unlike any previously imagined, Budai must learn to survive in a world where words and meaning are unconnected.”

The Finno-Ugrian Vampire (2002) by Noémi Szécsi, translated by Peter Sherwood (Stork Press, 2012)

“An entertaining story of a Budapest vampire dynasty. Jerne Voltampere’s Grandmother doesn’t look her age, but she is 284 years old. She looks like a young woman. No wonder, as every night she sucks the blood of assorted men. She is a vampire and wants her grandchild to follow the family tradition. Her Granddaughter, Jerne has just returned to Budapest after a posh education at an English college, Winterwood. Reincarnations of the Bronte sisters taught her to write fairy tales. Jerne writes children’s books, but they are considered too bloody to be published. Her Grandmother is adamant: Jerne will have to give up her literary ambitions and become a vampire. In the meanwhile, she takes an undemanding job as an editor. But the married couple who run the publishing house behave more and more suspiciously.”

Hungarian SFT: Novels (Part II)

The Sinistra Zone (1992) by Ádám Bodor, translated by Paul Olchváry (New Directions, 2013)

The Sinistra Zone (1992) by Ádám Bodor, translated by Paul Olchváry (New Directions, 2013)“Entering a weird, remote hamlet, Andrei calls himself “a simple wayfarer,” but he is in fact highly compromised: he has no identity papers. Taken under the wing of the military zone’s commander, Andrei is first assigned to guard the blueberries that supply a nearby bear reserve. He is surrounded by human wrecks, supernatural umbrellas, birds carrying plagues, albino twins. The bears — and an affair with a married woman — occupy Andrei until his protector is replaced by a new female commander, “a slender creature, quiet, diaphanous, like a dragonfly,” and yet an iron-fisted harridan. As things grow ever more alarming, Andrei becomes a “corpse watchman,” standing guard over the dead to check for any signs of life, and then ..”

The Mission (1971) by Péter Zsoldos, translated by András Szabados (Profiford Bt., 2018)

The Mission is itself a heady mix of ideas and thought-experiments concerning “transplanted personalities,” human evolution (both on Earth and on an unnamed extrasolar planet), first contact, and advanced technology. When a ship carrying explorers and scientists from Earth lands on a populated planet, the entire evolutionary course of the planet’s inhabitants is altered. The scientists’ ethnographic research into the society of seemingly-prehistoric humans that they find is interrupted when an unexplained accident kills or maims everyone on board. Gill, the cyberneticist and only-remaining crewmember able to function (for at least a little while) uses his last hours to frantically prepare the ship’s brain to carry out a necessary part of the Mission. The ship then lures Umu, one of the primitive humans, on board (through light and sound waves) and, with a special instrument called a “consociator,” melds together its consciousness with Gill’s, turning the barely-articulate human into a sophisticated cybernetics expert in the blink of an eye. From there, the new Gill/Umu captures more of Umu’s tribe and uploads the consciousnesses of the rest of the former crewmembers into them. The Mission, then, can continue, since, after all, the original crewmembers may be dead, but their minds (experience and knowledge) live on and can deliver to Earth the information that has been so painstakingly gathered about the planet…

The Bone Fire (2014) by György Dragomán, translated by Ottilie Mulzet (Mariner Books, 2021)

The Bone Fire (2014) by György Dragomán, translated by Ottilie Mulzet (Mariner Books, 2021)From an award-winning and internationally acclaimed European writer: A chilling and suspenseful novel set in the wake of a violent revolution about a young girl rescued from an orphanage by an otherworldly grandmother she’s never met

The Birds of Verhovina (2011) by Ádám Bodor, translated by Peter Sherwood (Jantar Publishing, 2021)

The reader arrives in Ádám Bodor’s world, the periphery of civilization, at the break of dawn. Adam, the foster son of Brigadier Anatol Korkodus is waiting at the dilapidated station for a boy who is arriving from a reformatory. Soon afterwards, Korkodus is arrested for unfathomable reasons. Yet this decaying and sinister world is not devoid of a certain joie de vivre: people eat gourmet dishes, point out their interlocutor’s hidden motives with incredibly dark humor and enjoy the region’s stunning natural beauty.

Disposable Bodies (Books 1-3) by Botond Markovics, translated by Austin Wagner (self-pub, 2023)

From Hungary’s leading science-fiction author Botond Markovics, Disposable Bodies is the multi award-winning standalone story of humanity’s desperate battle for a transhuman future, immortality, and freedom. Disposable Bodies won the Zsoldos Péter Literary Award and the Monolith Award in Hungary.

Allah’s Spacious Earth (2017) by Omar Sayfo, translated by Paul Olchváry (Syracuse UP, 2023)

Allah’s Spacious Earth is a stunningly fresh and timely political dystopia that depicts the tragic yet very real consequences of tensions between majority populations and Muslim minorities in the Western world. The novel is set in an imagined future where anti-Muslim sentiment and political pressure lead to a community being cut off from the rest of society. Told from the perspective of Nasim, a young Muslim living in the Zone—an urban area within one of the states forming the Pan-European Federation—the story follows his journey as he struggles with the restrictions imposed upon him along with the expectations of his community.

Hungarian SFT: Collections

Tales from Jókai by Mor Jókai, translated by R. Nisbet Bain (Jarrold & Sons, 1904)

Mixed collection of nine stories plus a biography of Jokai by Bain. Includes the novella “City of the Beast” (1856), a gaudy and highly dramatic account of the end of Atlantis; and three graphic contes cruels: “The Justice of Soliman” (1858), “The Sheriff of Caschau” (1858), and the bizarre tale of “The Hostile Skulls” (1879).

Voyage to Faremido and Capillaria (1916) by Frigyes Karinthy, translated by Paul Tabori (Corvina Press, 1965)

In Voyage, Gulliver is plucked from a WWI fighter plane and finds himself on a planet filled with sentient organic life forms that view humans as parasites, while Faremido takes up the age-old conflicts between the sexes. In both texts, Karinthy explored the same themes: “the utter inadequacy of Man, the futility of all our endeavors, the ridiculous pretense that we are sentient beings capable of progress” (intro by translator Paul Tabori)

The Magician’s Garden and Other Stories (1908) by Géza Csáth, translated by Jascha Kessler and Charlotte Rogers (Columbia UP, 1980)

The Magician’s Garden and Other Stories (1908) by Géza Csáth, translated by Jascha Kessler and Charlotte Rogers (Columbia UP, 1980)The Magician’s Garden offers a selection of stories ranging from impressionistic, metaphoric, and even surreal pieces to straightforward naturalism. An entire world and time is implicit in this group of twenty-four of his best stories.

The Black Maybe: Liminal Tales by Attila Veres, translated by Luca Karafiáth (Valancourt Books, 2022)

This volume collects ten of his best tales in English for the first time, ranging from weird fiction like ‘In the Snow, Sleeping’, in which a couple’s vacation to a health spa erodes into a surreal nightmare, to folk horror like ‘Return to the Midnight School’, in which the things that emerge from the soil in one rural farming community are bizarre and horrific, to Lovecraft-inspired tales like ‘Multiplied by Zero’, written as a wry travelogue in which a man sets out on a deadly holiday tour to explore Lovecraftian landscapes. And in the title story ‘The Black Maybe’, which Steve Rasnic Tem calls ‘one of the weirdest tales I’ve read in years’, a girl and her family escape the bustling city to experience farm life, only to discover with unimaginable horror the truth of what is really being harvested there.