Rachel S. Cordasco's Blog, page 14

May 31, 2022

Hebrew SFT: An Overview

Overview

Overview

SFT from Israel is wonderfully diverse, with science fiction, fantasy, magical realism, and everything in between. Acclaimed authors like Shimon Adaf, Orly Castel-Bloom, Etgar Keret, Dror Burstein, Ofir Touche Gafla, and Nir Yaniv move easily among genres, blurring boundaries and creating ever-more creative and unexpected stories. Certain themes–nationhood, identity, memory, trauma, family, religion–recur throughout Israeli speculative fiction, and thanks to the talented translators who bring these books into English, Anglophone readers can enjoy these stories and learn more about a fascinating culture.

ANTHOLOGIES

(2018)

(2021)

NOVELS

(1986)

(1997)

(2004)

(2013)

(2013)

(2014)

(2016)

(2017)

(2018)

(2018)

(2019)

(2020)

(2022)

[image error](2022)

(2022)

COLLECTIONS

(2002)

(2004)

(2006)

(2007)

(2008)

(2012)

(2012)

(2019)

SHORT STORIES

“Madame Bovary in Neve Tsedek” by Nurit Zarchi, translated by Miriyam Glazer (Dreaming the Actual: Contemporary Fiction and Poetry by Israeli Women Writers, 2000).

“Hunting a Unicorn” by Vered Tochterman, translated by the author (F&SF, 2003).

“A Wizard on the Road” by Nir Yaniv, translated by Lavie Tidhar (Shimmer, 2006).

“The Night the Buses Died” by Etgar Keret, translated by Miriam Shlesinger (BOMB, 2006).

“The Word of God” by Nir Yaniv, translated by Lavie Tidhar (Trabuco Road, 2006).

“The Levantine Experiments” by Guy Hasson, translated by ? (Chalomot Be’aspamia, 2007).

“Shira” by Lavie Tidhar, translated by the author (The Del Rey Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy, 2008).

“The Dream of the Blue Man” by Nir Yaniv, translated by Lavie Tidhar (Weird Tales, 2008).

“The Slows” by Gail Hareven, translated by Yaacov Jeffrey Green (The New Yorker, 2009).

“A Painter, a Sheep, and a Boa Constrictor” by Nir Yaniv, translated by Lavie Tidhar (Shimmer, 2009).

“Benjamin Schneider’s Little Greys” by Nir Yaniv, translated by Lavie Tidhar (Apex, 2009).

“Cinderers” by Nir Yaniv, translated by Lavie Tidhar (The Apex Book of World SF, 2009).

“The Believers” by Nir Yaniv, translated by the author (ChiZine, 2010).

“Velocity” by Ofir Touche Gafla, translated by Gilah Kahn-Hoffmann (Words Without Borders, 2012).

“Smile of the Monster” by Ido Sokolovsky, translated by Yehudit Keshet (World SF Blog, 2013).

“Women” by Matan Hermoni, translated by Yardenne Greenspan (Tel Aviv Noir, 2014).

“Clear Recent History” by Gon Ben Ari, translated by Yardenne Greenspan (Tel Aviv Noir, 2014).

“My Father’s Kingdom” by Shimon Adaf, translated by Yardenne Greenspan (Tel Aviv Noir, 2014).

“Death in Pyjamas” by Alex Epstein, translated by Yardenne Greenspan (Tel Aviv Noir, 2014).

“The Scapegoat Factory” by Ofir Touche Gafla, translated by ? (Jews vs. Zombies, 2015).

“Like a Coin Entrusted in Faith” by Shimon Adaf, translated by ? (Jews vs. Zombies, 2015).

“Ishmael” by Shimon Adaf, translated by Leanne Raday (The Short Story Project, 2016).

“A.: Only Through Death Will You Learn Your True Identity” by Etgar Keret, translated by Sondra Silverston (Wired, 2016).

“Jacob Wallenstein, Notes for a Future Biography” by Shay Azoulay, translated by the author (The Short Story Project, 2017).

“Another Love Story” by Uzi Weil, translated by Sondra Silverston (The Short Story Project, 2017).

“Dad with Mashed Potatoes” by Etgar Keret, translated by ? (Zoetrope, 2017).

“The Man Who Moved the Western Wall” by Uzi Weil, translated by Sondra Silverston (The Short Story Project, 2018).

Hebrew SFT

source: Encyclopedia Britannica

Overview

Novels (Part I)

Novels (Part II)

Collections

Anthologies

May 28, 2022

2022 Space Cowboy Award

A HUGE thank-you to Space Cowboy Books for honoring me with this year’s Space Cowboy Award! Check out the press release here and go buy a lot of books from them!

Retro Rockets

I was recently interviewed by the always-awesome Andrea Johnson for her Retro Rockets podcast. We talked about all things SFT and beyond. Give it a listen!

May 5, 2022

Daniel’s Reviews: The Bone Fire by György Dragomán

Daniel Haeusser reviews short works of SFT that appear both online and in print. He is an Assistant Professor in the Biology Department at Canisius College, where he teaches microbiology and leads student research projects with bacteria and bacteriophage. He’s also an associate blogger with the American Society for Microbiology’s popular Small Things Considered. Daniel reads broadly in English and French, and his book reviews can be found at Reading1000Lives or Skiffy & Fanty. You can also connect with him on Goodreads or Twitter.

“Build a pile of old bones, and burn away the shadows. Because from here on in, the shadows get deeper, the nights get longer. We’re heading into the dark, and we have to hang onto each other. So, we can only carry so much.”

“Build a pile of old bones, and burn away the shadows. Because from here on in, the shadows get deeper, the nights get longer. We’re heading into the dark, and we have to hang onto each other. So, we can only carry so much.”

These words, on the etymology of the word bonfire, come from the character Jamie Taylore in the Netflix series The Haunting of Bly Manor, but it nicely summarizes why The Bone Fire is such an apt title for Paul Olchváry’s recent English translation of György Dragomán’s novel Máglya (literally, Bonfire.) If I were to summarize the themes of the novel down to a simple statement, I could do no better than Jamie’s words.

Emma’s parents have died in a car accident, leaving the thirteen-year-old without a family, isolated and mournful within an orphanage. Until one day when an old woman shows up claiming to be the grandmother she didn’t know she still had, the estranged mother of Emma’s mother, come to take Emma home. There, Emma must depart childhood and discover her mature self amid the uncertainties of a new school, a changed political regime, and the mysteries of her family’s past. With Emma to help guide her is only her grandmother, this gentle, secluded figure who radiates mysticism and power, commanding respect even as a local outcast.

Though the novel is set in an unspecified Eastern European country soon falling the Fall of the Iron Curtain, the Hungarian Dragomán has stated that The Bone Fire is set in Transylvania, forming with his novel The White King the first two parts of a trilogy focused on this region of Romania that contains a large Hungarian population. Even if the plot of the novel doesn’t directly relate to political events, the lives and behavior of the characters are inextricably linked to the region and its history, from World War II through the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The Bone Fire opens with a successful revolution and release of Emma from an orphanage prison into freedom with someone who loves her. Things should feel like the start of a whole new season of life, of Spring. And yet… gothic dread and uncertainty continue to hang in the air. Both society on the grand level, and Emma on the personal level, have left the shadows, but are now met with more uncertainty of what the future would hold. Moreover, they haven’t let go of those bones of the past, the trauma and pains they carry. Only by releasing them together can they carry forward through the uncertain season of Winter ahead to then arrive at true growth.

At school and in town, Emma learns of the cruelty of the world, while also seeing some of that cruelty within herself. From her combative grandmother she also begins to learn of strength to overcome such cruelty, of beauty and magic. Gradually, Emma matures into a woman who learns the best of what her grandmother has to offer while also realizing how she can choose a different response to a cruel and unfair past than her grandmother and mother personally formed for themselves.

What little the novel has in terms of active plot is made up for through the richness of its setting, its prose, its characters, its heartbreaking emotion, and the tingle of its magic. It falls within the realms of fantasy or at least magical realism, although I find it interesting that this classification almost completely lies in the Pagan routes of its spiritual core. If the grandmother were less of a witch, and say one more devoted to the rituals and mysteries of Roman Catholicism, would readers still look at any of it as fantasy, or magical?

This is a brilliant novel about self-discovery, a coming-of-age within those shadows of the teen years before the Spring of adulthood. It’s a parallel for the self-discovery of a nation, or a people, formed through many past traumas and facing uncertain future. To make it through requires ritual, a bone fire cleaning of house that acknowledges those lost, the souls and sins of the past, a rite that strengthens the ties between the community of individuals who have survived to hang on to each other even amid failings.

May 4, 2022

Out This Month: May

“Gamma” by Oskar Källner, translated from the Swedish by Gordon James Jones (Clarkesworld, May 1)

“The Possibly Brief Life of Guang Hansheng” by Liang Qingsan, translated from the Chinese by Andy Dudak (Clarkesworld, May 1)

NOVELS

The Shining Sea by Suzuki Koji, translated from the Japanese by Brian Bergstrom (Vertical, May 31)

The Shining Sea by Suzuki Koji, translated from the Japanese by Brian Bergstrom (Vertical, May 31)

A young woman who attempted suicide by drowning has lost her memory and ability to speak. Her lover, a young man, is on a pelagic tuna fishing boat. What happened between them?

Nobody knows their own destiny. But what if you discover you only have a low chance of being happy in life?

From renowed author Koji Suzuki, the creator of the Ring series..

REVIEWS

Rachel Cordasco reviews More Zion’s Fiction in World Literature Today

Brianna Di Monda reviews When I Sing, Mountains Dance in Full Stop

April 27, 2022

Yardenne Greenspan on Translating Shimon Adaf

[image error]

[image error]

I’ve been reading the absolutely fantastic Lost Detective trilogy by Shimon Adaf and had the chance to ask its talented translator, Yardenne Greenspan, about her thoughts on translation and on Adaf’s work. Enjoy!

I’ve often been asked how I approach translating different genres, tones, or styles of writing, and I’m always stumped. It is not unlike the way I feel, as a writer, when people ask about my writing process. I don’t really have one! I don’t make a neat outline, I don’t have regular writing hours, and I don’t have steadfast rules about how to create. I just start, and see what comes to me. I’ve been watching the Netflix show Get Organized and noticing that the famous home organizers work in a similar fashion—rather than enforce their preconceived systems on another person’s space, they pull out all of the random stuff contained within that space—Tupperware, vintage T-shirts, holiday decorations—and sort through it until an inner logic emerges. Then they can begin to make the necessary connections and translate the mess into a system that makes sense.

Similarly, Matt Bell’s new writing guide, Refuse to be Done, promotes the concept of an exploratory first draft, in which, rather than carrying out a plan laid out in a premade outline, one follows intuition and inspiration to figure out the story as they go along. After a sufficient amount of exploration has been performed, the writer can then take a step back, look at what they have produced, and start shaping, rewriting, cutting, and adding.

The work of a translator is, of course, not quite as shrouded with mystery. The idea has already seeded and sprouted, the words already on the page. But the concept of learning the work while doing the work applies. My way to figure out how to translate a piece of writing is simply to start translating it. The rough draft will be, well, rough, but the beginning of it will certainly be the roughest part. As I go about putting words on the page, I will learn from the author’s work, as well as my own. I will begin to notice word choices, tone, sentence structure. I will observe the author’s unique use of punctuation, the originality of their similes, how much they rely on localized cultural touchstones or on slang.

When translating The Lost Detective trilogy, by Shimon Adaf, there were several specific elements to take into account. Shimon is first and foremost a poet, and poetic language is the central tool he uses in the building of his worlds. By utilizing distinct phrases, inventing unpredictable metaphors, and twisting up nouns into verbs, he is able to render any place, person, or situation fantastical. Sentences flip, images fold onto themselves, and a town or scenario familiar to me from my childhood in Israel are suddenly transformed into unheimlich.

Another important element I had to keep in mind is that Shimon has an encyclopedic knowledge of both modern literature and ancient Jewish texts, and that he references and plays with both in his writing. In the trilogy, he bends the genre of the detective novel, as well as science fiction tropes, in order to entice readers and repeatedly subvert their expectations. In any profession, it’s important to be aware of what we don’t know, and—coming from a Jewish secular background and having read very little genre fiction—I became aware very quickly that I had to check every reference and consult with Shimon about his sources to make sure I got it right.

But what I lack in specific literary knowledge I make up for in attention to detail. I often work from the heart, relying on what a piece of writing makes me feel. My favorite aspect of The Lost Detective trilogy is the atmosphere it creates—a sensation of bone-deep melancholy; a recognition of a hidden structure somewhere beneath the surface, deeming the world and the people in it simultaneously connected and utterly alone. The physical experience of being in the space of these books is delicious, and sustained me over the several years’ process of translating, revising, and editing them. These powerful impressions helped me come up with my own set of references—be they lingual or visual, literary of cinematic. I shared these with Shimon, and he often confirmed the connections I made. I recognized this tone and atmosphere on an interior level, and relied on my understanding of them heavily, using them as a way into the book, as an organizing principle, and as a lens with which to focus, categorize, and prioritize my translation.

April 6, 2022

2016 SFT on the Web

“Summer in Amber” by Susana Vallejo, translated from the Spanish by Lawrence Schimel, Persistent Visions Magazine.

“Salinger and the Koreans” by Han Song, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu, Tales of Our Time, the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) catalogue

“The Little Angel’s Exhumation” by Mariana Enriquez, translated from the Spanish by Joel Streicker, The Short Story Project.

JANUARY

“The Fruit of My Woman” by Han Kang, translated from the Korean by Deborah Smith (Granta).

“Broken Stars” by Tang Fei, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu (SQ Magazine).

“Everybody Loves Charles” by Bao Shu, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu (Clarkesworld).

FEBRUARY

MARCH

“Chimera” by Gu Shi, translated from the Chinese by S. Qiouyi Lu and Ken Liu (Clarkesworld).

“Let There Be Light” by Chen Qiufan, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu (Daily Science Fiction).

APRIL

“Balin” by Chen Qiufan, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu (Clarkesworld).

“The Hush Void” by Muhammad Khudayyir, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (The Common).

MAY

“Nothing to Declare” by Anabel Enríquez Piñeiro, translated from the Spanish by Hillary Gulley (Words Without Borders).

“Finished” by Han Song, translated from the Chinese by Nick Stember (Pathlight).

“The Bleeding Hands of Castaways” by Erick J. Mota, translated from the Spanish by Esther Allen (Words Without Borders).

“Away From Home” by Luo Longxiang, translated from the Chinese by Nick Stember (Clarkesworld).

“Interstellar Biochocolate Mousse à la solitaire . . . For Two” by Yoss, translated from the Spanish by Hillary Gulley (Words Without Borders).

“Freuds” (from Self-Reference ENGINE) by Toh EnJoe, translated from the Japanese by ??? (Haikasoru).

JUNE

“Landscape with Intruders” by Jean-Claude Dunyach, translated from the French by Sheryl Curtis (Blind Spot Magazine).

“Genesis” by Jeon Sam-hye, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur (Words Without Borders).

“The Snow of Jinyang” by Zhang Ran, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu and Carmen Yiling Yan (Clarkesworld Magazine).

JULY

“Pay Me” by Zdravka Evtimova, translated by ? (Electric Lit).

“The First Tree In the Forest” by Jean-Luc André d’Asciano, translated from the French by Edward Gauvin (Blind Spot Magazine).

“The New Abyss” by Paul Scheerbart, translated from the German by Daniel Ableev and Sarah Kassem (Weird Fiction Review).

AUGUST

“Madame Félidé Elopes” by K. A. Teryna, translated from the Russian by Anatoly Belilovsky (PodCastle).

“Alone, on the Wind” by Karla Schmidt, translated from the German by Lara Harmon (Clarkesworld).

“The Weight of Memories” by Liu Cixin, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu (Tor.com).

SEPTEMBER

“Ishmael” by Shimon Adaf, translated from the Hebrew by Leanne Raday (The Short Story Project).

“Record of a Growth” by Fanny Charrasse, translated from the French by Edward Gauvin (Blind Spot Magazine).

“The Triumph of Mechanics” by Karl Hans Strobl, translated from the German by Gio Clairval (Weird Fiction Review).

From “A Fair War” by Taiyo Fujii in Saiensu Fikushon 2016, translated from the Japanese by ??? (Haikasoru).

Excerpt from Nomansland, AZ by Boris Sandler, translated from the Yiddish by Sebastian Schulman (Words Without Borders).

“The Opposite and the Adjacent” by Liu Yang, translated from the Chinese by Nick Stember (Clarkesworld Magazine).

“The Ruins of Granada” by Ángel Ganivet, translated from the Spanish by Marian Womack (Weird Fiction Review).

“In Shadow” by Andreas Izquierdo, translated from the German by Rachel Hildebrandt (Weyward Sisters Publishing).

“Trick?” by Vincenzo Barone Lumaga, translated from the Italian by Rachel Cordasco (SFinTranslation.com).

OCTOBER

“The Boy in the Trunk” by Nicola Lombardi, translated from the Italian by J. Weintraub (Deadman’s Tome).

“The Onlookers” by Kathrin Röggla, translated from the German by Jake Schneider (The Short Story Project).

“Quadraturin” by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, translated from the Russian by Joanne Turnbull (The Short Story Project).

Excerpt from One Hundred Shadows by Hwang Jungeun, translated from the Korean by Jung Yewon (The Guardian).

Excerpt from Salome by Elaine Vilar Madruga, translated from the Spanish by David Shook (Weyward Sisters Publishing).

“Esmeralda” by Tamara Romero, translated from the Spanish by Lawrence Schimel (Strange Horizons).

“Gracia” by Susana Vallejo, translated from the Spanish by Lawrence Schimel (Strange Horizons).

“Dragon Boat” by Ge Liang, translated from the Chinese by Karen Curtis (Paper Republic).

“The Calculations of Artificials” by Chi Hui, translated from the Chinese by John Chu (Clarkesworld).

“Terpsichore” by Teresa P. Mira de Echeverría, translated from the Spanish by Lawrence Schimel (Strange Horizons).

NOVEMBER

“Heavens on Earth” (excerpt) by Carmen Boullosa, translated from the Spanish by Shelby Vincent (World Literature Today).

Smokopolitan: English issue (nr 7) (Polish sf)

“8 Minutes” by Mohamed Salah, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (The Offing).

“Where Did I Lose You?” by Fan Xiaoqing, translated from the Chinese by Paul Harris (Paper Republic).

“Two Young Women From Fuyang” by Mai Jia, translated from the Chinese by Yu Yan Chen (Paper Republic).

“Western Heaven” by Chen Hongyu, translated from the Chinese by Andy Dudak (Clarkesworld).

“The Northern Border” by Li Zishu, translated from the Chinese by Joshua Dyer (Paper Republic).

Dreams From Beyond: Anthology of Czech Speculative Fiction, ed. Julie Novakova (for Eurocon).

“Dragonworld” by Zhang Xinxin, translated from the Chinese by Helen Wang (Paper Republic).

“Electric Dreams” by Fabio Lastrucci, translated from the Italian by Rachel Cordasco (SFinTranslation.com).

DECEMBER

Excerpt from Mountains Oceans Giants by Alfred Döblin, translated from the German by Chris Godwin (In Translation).

“A.: Only Through Death Will You Learn Your True Identity” by Etgar Keret, translated from the Hebrew by Sondra Silverston (Wired).

“The Asphalt is Melting” by Antonella di Biase, translated from the Italian by ? (Motherboard).

“Spiderweb” by Mariana Enriquez, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell (The New Yorker).

“The Path to Freedom” by Tang Fei, translated from the Chinese by Xueting Christine Ni (Paper Republic).

“Painter of Stars” by Wang Yuan, translated from the Chinese by Andy Dudak (Clarkesworld).

April 2, 2022

Review: The World of the End by Ofir Touché Gafla

Hebrew title: עולם הסוף

translated by Mitch Ginsburg

Tor Books

June 25, 2013

368 pages

grab a copy here or or through your local independent bookstore or library

The World of the End reminds me of the TARDIS: both are larger on the inside than their outside would suggest. By “inside” and “outside,” in terms of the novel, I mean that the jacket summary (outside) belies the rich and varied story that we find inside (the novel itself). After all, we’re told that this is the story of an Israeli man named Ben Mendelssohn who, after the death of his wife, kills himself so he can rejoin her in the afterlife (if one exists, that is). Upon entering said afterlife, he can’t seem to find that wife, so he engages the services of a private detective. Weirdness ensues.

Just a few chapters into the novel and you’re hooked, or rather stuck, on the ferris-wheel of a plot that is at once engrossing and exhausting, just like the efforts of the protagonist as he runs all over the Other World searching for Marian. And that ferris-wheel reference I just made isn’t random- it’s the reason that Marian is dead in the first place. According to Ben, she was thrown off of the ride by a homeless man while she was on a field trip with her students. Later we learn that the murderer wasn’t homeless at all but a mentally-ill method actor. Nonetheless, Marian is dead and is nowhere to be found in the Other World.

Gafla plunges us unapologetically into this streamlined, highly-organized, efficient Other World, in which everyone lives in the highrise apartment that corresponds to the year, month, day, and time that they died. The dead can travel back in time—that is, to the areas (centuries) that came before. Thus, many dead take these minibuses (that are actually quite large) to the 17th century, for instance, to try out for Shakespeare’s new plays. Because yes, Shakespeare is having a great time in the Other World and has continued churning out the drama.

Most of the dead acclimate themselves to their new existence, but some don’t, and that’s where we ultimately find Marian. But wait…there’s another Marian. One who looks just like Ben’s wife but is…not actually dead. Gafla bounces us back and forth between the real world and the Other World as we follow this other Marian who apparently doesn’t know Ben and has been living in France for most of her life, moving to Israel only recently. The question then becomes: did Ben kill himself for nothing? Did Marian fake her death?

Another metaphor for this novel: when you open a thousand-piece puzzle box and dump the pieces on the floor (the first half of the novel). Then, as you start to put the pieces together, a clearer picture takes shape (the second half). Given the kind of reader and movie-watcher I am, the pieces came together quite late, but that’s likely because I enjoyed the weird suspense of wondering who and what Marian was. Indeed, not everyone in the Other World is a regular dead person. Some hang out temporarily in the Other World when they’re in comas in the real world. Those who died before being born have a special status (they’re called “aliases”) and basically run the Other World. Family trees in this realm are literally trees that are pruned, though in Ben’s family’s case, a renegade alias illegally uprooted his family tree, which is why eight of his family members died in quick succession.

Like I said before, this is just a peek into the complex plot involving two realms, multiple interlocking relationships, and the mystery of Marian’s life/death status. And it brings up larger questions of the afterlife, especially where it relates to Judaism. Though Ben and Marian are Israeli Jews, very little is said about religion in The World of the End, likely because these two are secular. Nonetheless, Judaism, unlike other major religions, has nothing to say about the before-life or after-life in its canonical text (the Torah). References to God and angels are everywhere in the Torah, but nothing about what happens before you’re born or after you die. Rabbis and others over the centuries, though, have discussed the subject, but “Heaven” and “Hell” are not a part of Jewish religious observance. The World of the End never mentions “Hell” or even “Purgatory,” and the Other World isn’t ever called “Heaven.” God is never mentioned, either. Gafla’s egalitarian realm, then, is a fascinating alternative space to which the dead are transported no matter how good or evil they were in life. While this has its advantages, it also means that stalkers who tormented specific people can continue to stalk them if they’re able to find them.

This is the only Gafla book in English translation, but you can find a couple of his stories in translation here and here. I encourage you to read as much Gafla as you can. You’ll be glad you did.

April 1, 2022

Out This Month: April

At the Edge of the Woods

by Masatsugu Ono, translated from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter (Two Lines Press, April 12)

At the Edge of the Woods

by Masatsugu Ono, translated from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter (Two Lines Press, April 12)

In an unnamed foreign country, a family of three is settling into a house at the edge of the woods. But something is off. A sound, at first like coughing and then like laughter, emanates from the nearby forest. Fantastical creatures, it is said, live out there in a castle where feudal lords reigned and Resistance fighters fell. When the mother, fearing another miscarriage, returns to her family’s home to give birth to a second child, father and son are left to their own devices in rural isolation. Haunted by the ever-present woods, they look on as the TV flashes with floods and processions of refugees. The boy brings a mysterious half-naked old woman home, but before the father can make sense of her presence, she disappears. A mail carrier with gnashing teeth visits to deliver nothing but gossip of violence. A tree stump in the yard refuses to die, no matter how generously the poison is applied. An allegory for alienation and climate catastrophe unlike any other, At the Edge of the Woods is a psychological tale where myth and fantasy are not the dominion of childhood innocence but the poison fruit borne of the paranoia and violence of contemporary life.

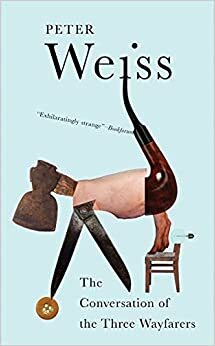

Conversation of the Three Wayfarers

by Peter Weiss, translated from the German by E.B. Garside (New Directions, April 22)

Conversation of the Three Wayfarers

by Peter Weiss, translated from the German by E.B. Garside (New Directions, April 22)

Conversation of the Three Wayfarers is a tale overheard, rather than told directly. Abel, Babel, and Cabel, the wayfarers, carry on a three-sided monologue, each reporting curious incidents—the effect is of three capers rolled into one: a steeplechase performed on a floating pontoon. But are they really three distinct individuals? Why do their lives blend in such a fantastic manner? Weiss’s strikingly original prose has an impossibly contained quality, with each sentence doing a perfect double-double backflip before neatly landing. This essential rediscovered work, from the masterful and acclaimed German modernist Peter Weiss, will be a delightful discovery for readers of Kafka, Musil, and Gombrowicz.

COLLECTIONS

Memories of Tomorrow by Mayi Pelot, translated from the Basque by Arrate Hidalgo (Aqueduct Press, April 1)

Memories of Tomorrow by Mayi Pelot, translated from the Basque by Arrate Hidalgo (Aqueduct Press, April 1)

Memories of Tomorrow collects a set of vibrant and enigmatic visions that emanated from one of the most creative minds of contemporary Basque literature. Often unnoticed by the established canon, Mayi Pelot has been uncovered and championed in recent years as one of the first genre authors in the language. Her publications, despite their brief span—from 1982 to 1992—undeniably laid the groundwork for future generations of Basque science fiction writers.