Sam Harris's Blog, page 24

March 30, 2013

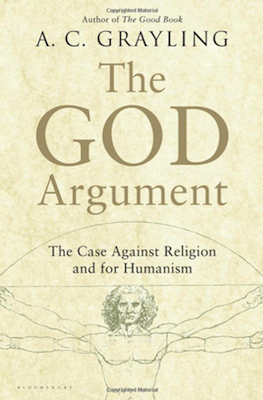

The God Argument

A.C. Grayling is Master of the New College of the Humanities (London). He is the author of the acclaimed Among the Dead Cities: The History and Moral Legacy of the WWII Bombing of Civilians in Germany and Japan, Descartes: The Life and Times of a Genius, Toward the Light of Liberty: The Struggles for Freedom and Rights That Made the Modern Western World, and, most recently, The Good Book: A Humanist Bible. A former fellow of the World Economic Forum at Davos and past chairman of the human rights organization June Fourth, he contributes frequently to the Times, Financial Times, Economist, New Statesman, and Prospect. Grayling’s play “Grace,” co-written with Mick Gordon, was acclaimed in London and New York. He is also an advisor to my nonprofit foundation, Project Reason.

Anthony’s new book is The God Argument: The Case against Religion and for Humanism.

***What is your religious background?

I was brought up in a non-religious household and was first presented with religious ideas in school; they did not persuade me but on the contrary seemed non-rational and misleading. In the study of history I became aware of the effects of religious divisions and sectarianism on individuals and societies, and came to think that freedom from religious influence is a human rights issue. I am an atheist, a secularist and a humanist.

Perhaps you should clarify the differences between atheism, secularism, and humanism.

The first is a metaphysical view about what the universe contains (about what exists), the second is a commitment to separation of religious organizations from state organizations, and the third is the ethical outlook of any reflective person who does not have any religious beliefs or commitments.

What are the roots of humanism, in your view?

The tradition of ethical thought stemming from classical antiquity is the foundation of humanism (and is a thousand years older than Christianity)—the study of these ideas suggests their living applicability to life, and I have been keen to alert people to this fact. Often people ask “what is the alternative to religion as a philosophy of life,” and the emphatic answer is: humanism.

Humanism is a philosophical starting point for reflection on how one should live, according to one’s own talents and interests and under the government of respecting others and not doing them harm, allowing them their own quest for an individual good life.

Do you think a person can be both a humanist and a person of faith?

No, religion and humanism are not consistent—unless you mean ‘humanism’ in the Renaissance sense, where it denoted the study of classical literature. But this study soon showed people that the ideas and outlook of classical thought is at odds with religion, which is why humanism is now a secular philosophy.

Do you have any advice on how to raise children as humanists in a world where most people are religious?

Easy—make children conscious of their responsibilities to others, help them to be clear-eyed and to think, question, always ask for the evidence and arguments in support of any proposition—and explain how the legacy of mankind’s ignorant past survives in religious beliefs and practices, and what role these have in social life as a result of their historical embedding.

What would you say to someone who argues that we need religion, whether or not any religious doctrine is true, because religion gives us spirituality, rituals, etc.?

I say that such pleasures and relaxations as a country walk, dinner with friends, an afternoon in an art gallery, attending a concert or the theatre, intimacy with a loved one, lying on a beach in the sun, reading and learning, making things, are all “spiritual exercises” in their refreshment, strengthening and promotion of connections with others and the world—these are the only “rituals” and observances required for an intelligent appreciation of what is good and possible in human life.

There’s one meme I find especially galling these days—it’s the claim that atheists (or the “new atheists”) are just as dogmatic as religious fundamentalists are. This is one of those zombie ideas that, no matter how many times you kill it, it comes shambling back at you. I’m wondering what your response to it is.

There are two components to the answer: One needs to explain what “dogma” means, viz. a teaching to be accepted on authority not enquiry, and one needs to explain that robust opposition to religion in its too-common forms of bigotry, anti-science, anti-LGBT, anti-women, to say nothing of terrorism (and to ‘moderate’ religion as the burka for all this, as you point out), is justified, and cannot be effected by compromise and soft-speaking. Slavery would never have been abolished by such means.

March 8, 2013

A Print Edition of LYING

(Cover by David Drummond)

A new edition of my short book, Lying, will be published as a hardcover in the fall. The book will contain responses to the best questions and criticisms I receive from readers, and this new material will be included in a revised edition of the e-book.

So this is an appeal to the wisdom of the crowd: If you have read Lying and have doubts about my argument, please be in touch through the contact page of this website by June 1st. And if your question or comment makes it into the appendix, or causes me to alter a single word of the main text, I will send you signed and personalized copies of all my books—The End of Faith, Letter to a Christian Nation, The Moral Landscape, Free Will, and the revised edition of Lying—in the fall.

Thanks for reading—and thanks, in advance, for your help.—SH

January 22, 2013

The Power of Bad Incentives

The Edge Annual Question — 2012

WHAT *SHOULD* WE BE WORRIED ABOUT?

The Edge Annual Question — 2012

WHAT *SHOULD* WE BE WORRIED ABOUT?

By Sam Harris

Imagine that a young, white man has been falsely convicted of a serious crime and sentenced to five years in a maximum-security penitentiary. He has no history of violence and is, understandably, terrified at the prospect of living among murderers and rapists. Hearing the prison gates shut behind him, a lifetime of diverse interests and aspirations collapses to a single point: He must avoid making enemies so that he can serve out his sentence in peace.

Unfortunately, prisons are places of perverse incentives—in which the very norms one must follow to avoid becoming a victim lead inescapably toward violence. In most U.S. prisons, for instance, whites, blacks, and Hispanics exist in a state of perpetual war. This young man is not a racist, and would prefer to interact peacefully with everyone he meets, but if he does not join a gang he is likely to be targeted for rape and other abuse by prisoners of all races. To not choose a side is to become the most attractive victim of all. Being white, he likely will have no rational option but to join a white-supremacist gang for protection.

So he joins a gang. In order to remain a member in good standing, however, he must be willing to defend other gang members, no matter how sociopathic their behavior. He also discovers that he must be willing to use violence at the tiniest provocation—returning a verbal insult with a stabbing, for instance—or risk acquiring a reputation as someone who can be assaulted at will. To fail to respond to the first sign of disrespect with overwhelming force, is to run an intolerable risk of further abuse. Thus, the young man begins behaving in precisely those ways that make every maximum security prison a hell on earth. He also adds further time to his sentence by committing serious crimes behind bars.

A prison is perhaps the easiest place to see the power of bad incentives. And yet in many other places in our society, we find otherwise normal men and women caught in the same trap and busily making life for everyone much less good than it could be. Elected officials ignore long-term problems because they must pander to the short-term interests of voters. People working for insurance companies rely on technicalities to deny desperately ill patients the care they need. CEOs and investment bankers run extraordinary risks—both for their businesses and for the economy as a whole—because they reap the rewards of success without suffering the penalties of failure. Lawyers continue to prosecute people they know to be innocent (and defend those they know to be guilty) because their careers depend upon winning cases. Our government fights a war on drugs that creates the very problem of black market profits and violence that it pretends to solve….

We need systems that are wiser than we are. We need institutions and cultural norms that make us better than we tend to be. It seems to me that the greatest challenge we now face is to build them.

January 2, 2013

The Riddle of the Gun

(Photo by Zorin Denu)

Fantasists and zealots can be found on both sides of the debate over guns in America. On the one hand, many gun-rights advocates reject even the most sensible restrictions on the sale of weapons to the public. On the other, proponents of stricter gun laws often seem unable to understand why a good person would ever want ready access to a loaded firearm. Between these two extremes we must find grounds for a rational discussion about the problem of gun violence.

Unlike most Americans, I stand on both sides of this debate. I understand the apprehension that many people feel toward “gun culture,” and I share their outrage over the political influence of the National Rifle Association. How is it that we live in a society in which one of the most compelling interests is gun ownership? Where is the science lobby? The safe food lobby? Where is the get-the-Chinese-lead-paint-out-of-our-kids’-toys lobby? When viewed from any other civilized society on earth, the primacy of guns in American life seems to be a symptom of collective psychosis.

Most of my friends do not own guns and never will. When asked to consider the possibility of keeping firearms for protection, they worry that the mere presence of them in their homes would put themselves and their families in danger. Can’t a gun go off by accident? Wouldn’t it be more likely to be used against them in an altercation with a criminal? I am surrounded by otherwise intelligent people who imagine that the ability to dial 911 is all the protection against violence a sane person ever needs.

But, unlike my friends, I own several guns and train with them regularly. Every month or two, I spend a full day shooting with a highly qualified instructor. This is an expensive and time-consuming habit, but I view it as part of my responsibility as a gun owner. It is true that my work as a writer has added to my security concerns somewhat, but my involvement with guns goes back decades. I have always wanted to be able to protect myself and my family, and I have never had any illusions about how quickly the police can respond when called. I have expressed my views on self-defense elsewhere. Suffice it to say, if a person enters your home for the purpose of harming you, you cannot reasonably expect the police to arrive in time to stop him. This is not the fault of the police—it is a problem of physics.

Like most gun owners, I understand the ethical importance of guns and cannot honestly wish for a world without them. I suspect that sentiment will shock many readers. Wouldn’t any decent person wish for a world without guns? In my view, only someone who doesn’t understand violence could wish for such a world. A world without guns is one in which the most aggressive men can do more or less anything they want. It is a world in which a man with a knife can rape and murder a woman in the presence of a dozen witnesses, and none will find the courage to intervene. There have been cases of prison guards (who generally do not carry guns) helplessly standing by as one of their own was stabbed to death by a lone prisoner armed with an improvised blade. The hesitation of bystanders in these situations makes perfect sense—and “diffusion of responsibility” has little to do with it. The fantasies of many martial artists aside, to go unarmed against a person with a knife is to put oneself in very real peril, regardless of one’s training. The same can be said of attacks involving multiple assailants. A world without guns is a world in which no man, not even a member of Seal Team Six, can reasonably expect to prevail over more than one determined attacker at a time. A world without guns, therefore, is one in which the advantages of youth, size, strength, aggression, and sheer numbers are almost always decisive. Who could be nostalgic for such a world?

Of course, owning a gun is not a responsibility that everyone should assume. Most guns kept in the home will never be used for self-defense. They are, in fact, more likely to be used by an unstable person to threaten family members or to commit suicide. However, it seems to me that there is nothing irrational about judging oneself to be psychologically stable and fully committed to the safe handling and ethical use of firearms—if, indeed, one is.[]

Carrying a gun in public, however, entails even greater responsibility than keeping one at home, and in most states the laws reflect this. Like many gun-control advocates, I have serious concerns about letting ordinary citizens walk around armed.[] Ordinary altercations can become needlessly deadly in the presence of a weapon. A scuffle that exposes a gun in a person’s waistband, for instance, can quickly become a fight to the death—where the first person to get his hands on the weapon may feel justified using it in “self-defense.” Most people seem unaware that knives present a similar liability. According to Gallup, 16 percent of American men carry knives for personal protection. I am quite sure that most of those men have not thought through the legal, ethical, and game-theoretical implications of drawing a blade in a moment of conflict. It is true that brandishing a weapon (whether a gun or a knife) sometimes preempts further violence. But, emotions being what they are, it often doesn’t—and the owner of the weapon can find himself resorting to deadly force in a circumstance that would not otherwise have called for it.

Some Facts About Guns

Fifty-five million kids went to school on the day that 20 were massacred at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut. Even in the United States, therefore, the chances of a child’s dying in a school shooting are remote. As my friend Steven Pinker demonstrates in his monumental study of human violence, The Better Angels of Our Nature, our perception of danger is easily distorted by rare events. Is gun violence increasing in the United States? No. But it certainly seems to be when one recalls recent atrocities in Newtown and Aurora. In fact, the overall rate of violent crime has fallen by 22 percent in the past decade (and 18 percent in the past five years).

We still have more guns and more gun violence than any other developed country, but the correlation between guns and violence in the United States is far from straightforward. Thirty percent of urban households have at least one firearm. This figure increases to 42 percent in the suburbs and 60 percent in the countryside. As one moves away from cities, therefore, the rate of gun ownership doubles. And yet gun violence is primarily a problem in cities. It is the people of Detroit, Oakland, Memphis, Little Rock, and Stockton who are at the greatest risk of being killed by guns.

In the weeks since the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary, advocates of stricter gun control have called for a new federal ban on “assault weapons” and for reductions in the number of concealed-carry permits issued to private citizens. But the murder rate has fallen precipitously since the federal ban on assault weapons expired in 2004, and this was also a period in which millions of Americans began to carry their guns in public. Many proponents of gun control have observed that the AR 15, the gun that Adam Lanza used to murder 20 children in Newtown, is now the most popular rifle in America. But only 3 percent of murders in the U.S. are committed with rifles of any type.

Seventy mass shootings have occurred in the U.S. since 1982, leaving 543 dead. These crimes were horrific, but 564,452 other homicides took place in the U.S. during the same period. Mass shootings scarcely represent 0.1 percent of all murders. When talking about the problem of guns in our society, it is easy to lose sight of the worst violence and to become fixated on symbols of violence.[]

Of course, it is important to think about the problem of gun violence in the context of other risks. For instance, it is estimated that 100,000 Americans die each year because doctors and nurses fail to wash their hands properly. Measured in bodies, therefore, the problem of hand washing in hospitals is worse than the problem of guns, even if we include accidents and suicides. But not all deaths are equivalent. A narrow focus on mortality rates does not always do justice to the reality of human suffering. Mass shootings are a marginal concern, even relative to other forms of gun violence, but they cause an unusual degree of terror and grief—particularly when children are targeted. Given the psychological and social costs of certain low-frequency events, it does not seem irrational to allocate disproportionate resources to prevent them.

We should also remember that mass killings do not depend on guns. Much was made in the press about the fact that on the very day 20 children were murdered in Newtown, a man with a knife attempted a similar crime at an elementary school in China. At The Atlantic, James Fallows wrote:

Twenty-two children injured. Versus, at current count, 18 20 little children and nine eight other people shot dead. That’s the difference between a knife and a gun.

Guns don’t attack children; psychopaths and sadists do. But guns uniquely allow a psychopath to wreak death and devastation on such a large scale so quickly and easily. America is the only country in which this happens again—and again and again. You can look it up.

This is more tendentious than it might sound. There has been an epidemic of knife attacks on schoolchildren in China in the past two years. As Fallows certainly knows—he is, after all, an expert on China—in some instances several children were murdered. In March of 2010, eight were killed and five injured in a single incident. This was as bad as many mass shootings in the U.S. I am not denying that guns are more efficient for killing people than knives are—but the truth is that knives are often lethal enough. And the only reliable way for one person to stop a man with a knife is to shoot him.

It is reasonable to wish that only virtuous people had guns, but there are now nearly 300 million guns in the United States, and 4 million new ones are sold each year. A well-made gun can remain functional for centuries. Any effective regime of “gun control,” therefore, would require that we remove hundreds of millions of firearms from our streets. As Jeffrey Goldberg points out in The Atlantic, it may no longer be rational to hope that we can solve the problem of gun violence by restricting access to guns—because guns are everywhere, and the only people who will be deterred by stricter laws are precisely those law-abiding citizens who should be able to possess guns for their own protection and who now constitute one of the primary deterrents to violent crime. This is, of course, a familiar “gun nut” talking point. But that doesn’t make it wrong.

Another problem with liberal dreams of gun control is that the kinds of guns used in the vast majority of crimes would not fall under any plausible weapons ban. And advocates of stricter gun laws who claim to respect the rights of “sportsmen” or “hunters,” and to recognize a legitimate need for “home defense,” simply give the game away at the outset. The very guns that law-abiding citizens use for recreation or home defense are, in fact, the problem.

In the vast majority of murders committed with firearms—even most mass killings—the weapon used is a handgun. Unless we outlaw and begin confiscating handguns, the weapons best suited for being carried undetected into a classroom, movie theater, restaurant, or shopping mall for the purpose of committing mass murder will remain readily available in the United States. But no one is seriously proposing that we address the problem on this level. In fact, the Supreme Court has recently ruled, twice (in 2008 and 2010), that banning handguns would be unconstitutional.

Nor is anyone advocating that we deprive hunters of their rifles. And yet any rifle suitable for killing deer is just the sort of gun that will allow even an unskilled shooter to wreak absolute havoc upon innocent men, women, and children at a range of several hundred yards. There is, in fact, no marksman on earth who can shoot a handgun as accurately at distance as you would be able to shoot a rifle fitted with a scope after a few hours of practice. This difference in accuracy between short and long guns must be experienced to be understood. Having understood it, you will in no way be consoled to learn that a madman ensconced on the rooftop of a nearby building is armed merely with a “hunting rifle” that is legal in all 50 states.

The problem, therefore, is that with respect to either factor that makes a gun suitable for mass murder—ease of concealment (a handgun) or range (a rifle)—the most common and least stigmatized weapons are among the most dangerous. Gun-control advocates seem perversely unaware of this. As a consequence, we routinely hear the terms “semi-automatic” and “assault weapon” intoned with misplaced outrage and awe. It is true that a semi-automatic pistol allows a person to shoot and reload slightly more efficiently than a revolver does. But a revolver can be reloaded surprisingly quickly with a device known as a speed loader. (These have been in use since the 1970s.)[] It is no exaggeration to say that if we merely had 300 million vintage revolvers in this country, we would still have a terrible problem with gun violence, with no solution in sight. And any person entering a school with a revolver for the purpose of killing kids would most likely be able to keep killing them until he ran out of ammunition, or until good people arrived with guns of their own to stop him.

According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report, 47 percent of all murders in the U.S. are committed with handguns. Again, only 3 percent are committed with rifles (of any type). Twice as many murderers (6 percent) use nothing but their bare hands. Thirteen percent use knives. Although a semi-automatic rifle like the one Adam Lanza carried in Newtown offers a terrifying advantage over a handgun at distances beyond 20 yards or so, I see no reason to think that the children he murdered would be alive today had he been armed with only a pistol (he is reported to have shot them repeatedly and at close range). The worst mass shooting in U.S. history occurred at Virginia Tech in 2007. Thirty-two people were killed and seventeen injured. The shooter carried two handguns (a Glock 9 mm and a Walther .22) of a make and caliber that will remain legal and ubiquitous unless all handguns are banned. (Again, this is not going to happen.)

It is true that rifles like the one used in the Newtown attack fire rounds at a much higher velocity than handguns do. These bullets also tend to tumble and fragment in the body, which makes them more lethal. However, one cannot say in every case that an assault weapon in the wrong hands is a greater threat to innocent life than a handgun. Rifle rounds travel at such high velocity that they sometimes pass through a person’s body before tumbling or fragmenting—doing less damage than one would expect from a handgun round. Conversely, these bullets are so light and frangible that they are sometimes stopped by barriers such as doors and wallboard. It is also generally easier to grab the barrel of a rifle and wrest it away from a shooter than it is with a handgun. And rifles are far more difficult to conceal. Approaching the doors of Sandy Hook Elementary, Adam Lanza probably looked every inch the dangerous lunatic with a gun. Had an armed guard been at the school, this could have allowed for a defensive response. Given these facts, it is difficult to say that assault weapons pose a greater risk to the public than handguns do.

Regarding ammunition itself, there is not much more to say, because any type suitable for home defense or hunting—and, therefore, bound to remain legal as long as guns are sold—is also perfect for killing innocent people. The only other variable to consider is the number of rounds a gun can hold, because this dictates the frequency with which a shooter must pause to reload. Here the path to increased public safety is reasonably clear. In California and New York, for instance, one cannot buy magazines that hold more than 10 rounds. As a consequence, the moment at which a shooter can be tackled by bystanders comes after every 10 shots. Ten is a lot better than 30, of course, but it still requires the action of a true hero (probably several) who just happens to be standing close enough to the shooter to attempt to bring him down, and who is lucky enough to be alive and uninjured after the last barrage. As Goldberg notes, with understandable despair and amazement, the security plans at many schools encourage students to spontaneously arm themselves with pencils and laptops and engage a shooter directly in defense of their lives—all the while forbidding the lawful possession of firearms on campus, no matter what a person’s training. As Goldberg says, “The existence of these policies suggests that universities know they cannot protect their students during an armed attack.”

More Guns Are Not The Answer—Until They Are

Coverage of the Newtown tragedy and its aftermath has been generally abysmal. In fact, I have never seen the “liberal media” conform to right-wing caricatures of itself with such alacrity. I have read articles in which literally everything said about firearms and ballistics has been wrong. I have heard major newscasters mispronounce the names of every weapon and weapons manufacturer more challenging than “Colt.” I can only imagine the mirth it has brought gun-rights zealots to see “automatic” and “semi-automatic” routinely confused, or to hear a major news anchor ominously declare that the shooter had been armed with a “Sig Sauzer” pistol. This has been more than embarrassing. It has offered a thousand points of proof that “liberal elites” don’t know anything about what matters when bullets start flying.

Consider the sneering response of the New York Times editorial page to Wayne LaPierre, the NRA vice president, after he suggested that we station a police officer at every school in the country:

His solution to the proliferation of guns, including semiautomatic rifles designed to kill people as quickly as possible, is to put more guns in more places. Mr. LaPierre would put a police officer in every school and compel teachers and principals to become armed guards…. Mr. LaPierre said the Newtown killing spree “might” have been averted if the killer had been confronted by an armed security guard. It’s far more likely that there would have been a dead armed security guard—just as there would have been even more carnage if civilians had started firing weapons in the Aurora movie theater.

The phrase “designed to kill people as quickly as possible” should tell us everything we need to know about the author’s grasp of the issue. The entire editorial is worth reading, in fact, because it makes the NRA’s response to Newtown seem enlightened by comparison.

Gun-control advocates appear unable to distinguish situations in which a gun in the hands of a good person would be useless (or worse) and those in which it would be likely to save dozens of innocent lives. They are eager to extrapolate from the Aurora shooting to every other possible scene of mass murder. However, a single gunman trying to force his way into a school, or roaming its hallways, or even standing in a classroom surrounded by dead and dying children, would be far easier to engage effectively—with a gun—than James Holmes would have been in a dark and crowded movie theater. Even in the case of the Aurora shooting, it is not ludicrous to suppose that everyone might have been better off had a well-trained person with a gun been at the scene. The liberal commentariat seems to have no awareness of what “well-trained” signifies. It happens to include an understanding of what to do and what not to do when the danger of shooting innocent bystanders exists. The fact that bystanders do occasionally get shot, even by police officers, does not prove that putting guns in the hands of good people would be a bad idea. Gun-control advocates seem always to imagine the worst possible scenario: legions of untrained, delusional vigilantes producing their weapons at a pin drop and firing indiscriminately into a crowd.

Most liberals responded derisively to the NRA’s suggestion that having armed and vetted men and women in our schools could save lives. Some pointed to a public-service announcement put out by the city of Houston (funded by the Department of Homeland Security), in which the possibility of having guns on the scene was never discussed. Several commentators held up this training video in support of the creed “More guns are not the answer.” Please take a few minutes to watch this footage. Then try to imagine how a few armed civilians could respond during an attack of this kind. To help your imagination along, watch this short video, in which a motel clerk carrying a concealed weapon shoots an armed robber. The situation isn’t perfectly analogous—the wisdom of using deadly force in what might be only a robbery is at least debatable. But is it really so difficult to believe that the shooter might have been helpful during an incident of the sort depicted in Houston?

Needless to say, it is easy to see how things can go badly when anyone draws a firearm defensively. But when an armed man enters an office building, restaurant, or school for the purpose of murdering everyone in sight, things are going very badly already. Imagine being one of the people in the Houston video trapped in the office with no recourse but to hide under a desk. Would you really be relieved to know that up until that moment, your workplace had been an impeccably gun-free environment and that no one, not even your friend who did three tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, would be armed? If you found yourself trapped with others in a conference room, preparing to attack the shooter with pencils and chairs, can you imagine thinking, “I’m so glad no one else has a gun, because I wouldn’t want to get caught in any crossfire”? Despite what the New York Times and dozens of other editorial pages have avowed in the weeks since Newtown, it isn’t a vigilante delusion to believe that guns in the hands of good people would improve the odds of survival in deadly encounters of this kind. The delusion is to think that everyone would be better off defending his or her life with furniture.[]

Unarmed people can be trained to respond intelligently to violent emergencies, and the appropriate drills seem well worth doing. (If you watch the linked video, you will see that rather than simply terrifying students, these drills can be fun and empowering.) Of course, there are no guarantees when tackling a man with a gun, and training of this kind makes sense only for students above a certain age. But such “active shooter” drills, if widely taught, would probably reduce the threat of mass killings. However, when a massacre is under way, nothing can substitute for the presence of other armed men and women who have been trained to fight with guns. That is why one bothers to call the police. And those who are horrified at the idea of stationing a police officer in every school should be obliged to tell us how long they would like to wait for the police to arrive in the event that they are needed. Declaring schools to be “gun-free zones” makes them especially good places to commit mass murder—this is more NRA propaganda that happens to be true. With the exception of the attack on U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in Tucson in 2011, every mass shooting since 1950 has taken place where civilians are forbidden to carry firearms [Correction 1/11/13: I have been informed that this mall is a gun-free zone too.].

As the parent of a daughter in preschool, I can scarcely imagine the feelings of terror, helplessness, and grief endured by the parents of Newtown. But when I contemplate atrocities of this kind, I do not think of “gun control”—because it seems extraordinarily unlikely that a deranged and/or evil person will ever find it difficult to acquire a firearm in the United States. Rather, I think of how differently the situation might have evolved if the school had had an armed (and, I have to emphasize, well-trained) security guard on campus. I also think of how differently things might have gone if the shooter, who seems to have shown signs of mental illness for years, had been more intrusively engaged by society prior to the attack.

But my thoughts soon return to the armed guard, because our laws generally do not allow us to prevent crime—even when a person’s bad intentions are reasonably well understood. As someone who has received repeated death threats—several of them from the same person—I know that little can be done in advance of an attack. In fact, our laws do not even allow us to keep the most violent criminals permanently off our streets. Eighty percent of the people languishing in our maximum-security prisons will eventually be released back into society—many having become more violent for their time behind bars—and 70 percent of those will return to prison after committing further crimes. We live in a country where nonviolent drug offenders receive life sentences but a man who rapes a fifteen-year-old girl and cuts her arms off with a hatchet can be paroled for good behavior after eight years (only to kill again). I do not know what explains this impossible distortion of priorities, but given that it exists, I believe that good, trustworthy, and well-trained people should have guns.

Preventing low-frequency events like school shootings is probably impossible. If we enact laws that allow us to commit young men who merely scare us to mental institutions, we will surely commit thousands upon thousands of young men who would never have harmed anyone. This leads me to believe that if we care about minimizing the harm caused by the next school shooter, we should focus on stopping him at the doors of the school. To be sure, hiring enough guards to protect our nation’s schools would be a daunting task. The security industry is notorious for poor quality control, and there is even reason to worry that some police officers have insufficient training with their guns. But it is clearly possible to hire as many competent guards as we want, should this become a national priority. This is entirely a question of money, not of whether it is possible to enlist, train, and equip 100,000 highly qualified men and women to protect our children.

As I said at the outset, I do not know how we can solve the problem of gun violence. A renewed ban on “assault weapons”—nearly the only concrete measure that anyone is talking about—will do very little to make our society safer. It is not, as many advocates seem to believe, an important “first step” in achieving a sane policy with respect to guns. It seems likely to be a symbolic step that delays real thinking about the problem of guns for another decade or more. By all means, let us ban these weapons. But when the next lunatic arrives at a school armed with legal pistols and a dozen ten-round magazines, we should be prepared to talk about how an assault weapons ban was a distraction from the real issue of gun violence.

One of the greatest impediments to actually solving the riddle of guns in our society is the pious concern that many people have about the intent of the Second Amendment. It should hardly need to be said that despite its brilliance and utility, the Constitution of the United States was written by men who could not possibly have foreseen every change that would occur in American society in the ensuing centuries. Even if the Second Amendment guaranteed everyone the right to possess whatever weapon he or she desired (it doesn’t), we have since invented weapons that no civilian should be allowed to own. In fact, it can be easily argued that original intent of the Second Amendment had nothing to do with the right of self-defense—which remains the ethical case to be made for owning a firearm. The amendment seems to have been written to allow the states to check the power of the federal government by maintaining their militias. Given the changes that have occurred in our military, and even in our politics, the idea that a few pistols and an AR 15 in every home constitutes a necessary bulwark against totalitarianism is fairly ridiculous. If you believe that the armed forces of the United States might one day come for you—and you think your cache of small arms will suffice to defend you if they do—I’ve got a black helicopter to sell you.

We could do many things to ensure that only fully vetted people could get a licensed firearm. The fact that guns in the U.S. can be legally purchased from private sellers without background checks on the buyers (the so-called “gun show loophole”) is terrifying. Getting a gun license could be made as difficult as getting a license to fly an airplane, requiring dozens of hours of training. I would certainly be happy to see policy changes like this. In that respect, I support much stricter gun laws. But I am under no illusions that such restrictions would make it difficult for bad people to acquire guns illegally. Given the level of violence in our society, the ubiquity of guns, and the fact that our penitentiaries function like graduate schools for violent criminals, I think sane, law-abiding people should have access to guns. In that respect, I support the rights of gun owners.

Finally, I have said nothing here about what might cause a person like Adam Lanza to enter a school for the purpose of slaughtering innocent children. Clearly, we need more resources in the areas of childhood and teenage mental health, and we need protocols for parents, teachers, and fellow students to follow when a young man in their midst begins to worry them. In the majority of cases, someone planning a public assassination or a mass murder will communicate his intentions to others in advance of the crime. People need to feel personally responsible for acting on this information—and the authorities must be able to do something once the information gets passed along. But again, any law that allows us to commit or imprison people on the basis of a mere perception of risk would guarantee that large numbers of innocent people will be held against their will.

Rather than new laws, I believe we need a general shift in our attitude toward public violence—wherein everyone begins to assume some responsibility for containing it. It is worth noting that this shift has already occurred in one area of our lives, without anyone’s having received special training or even agreeing that a change in attitude was necessary: Just imagine how a few men with box cutters would now be greeted by their fellow passengers at 30,000 feet.

Perhaps we can find the same resolve on the ground.

The importance of storing and handling firearms safely, and of never growing complacent about this, is impossible to exaggerate. In 2010, 606 people died in accidental shootings, 62 of them children. But deadly risks are everywhere: Six times as many people accidentally drown each year (in non-boating-related incidents), and 700 of them are children—this is in a country where 47 percent of homes have guns. There is no question that putting a pool in your yard is as serious a decision as buying a gun. This is another point about which “gun nuts” happen to be correct.↩

According to one source cited by Goldberg, concealed-carry permit holders not only commit fewer crimes than members of the general public—they commit fewer crimes than police officers. It is certainly possible that in states with stringent requirements, civilians who take the trouble to go through the permitting process will be an unusually scrupulous bunch. Eight million people have been issued concealed-carry permits in the United States. But many more gun owners carry illegally, or legally in states that do not require permits (Gallup reports that 12 percent of Americans say they sometimes carry a gun for self-defense.)↩

Although Adam Lanza seems to have been the prototypical mass shooter—white, male, mentally unstable, and living outside a large city—the epidemic of gun crime in America is, in part, the product of urban gang activity. The black community continues to commit and to suffer more than its fair share of this violence. According to the Children’s Defense Fund, gun deaths among white children and teens have decreased by 44 percent over the past three decades, while deaths among black children and teens increased by 30 percent. Blacks account for only 15 percent of the youth population but suffer 45 percent of all child and teen gun deaths. Black males aged 15 to 19 are eight times as likely as their white peers, and two-and-a-half-times as likely as Hispanics, to die by a bullet.

The problem of gangs is distinct from the problem of guns. Gang membership answers to a variety of social needs—protection and status foremost among them. But, as is the case with many social problems, gangs answer to a need that they themselves create. A person’s reputation within a gang depends upon his demonstrated willingness to harm outsiders. Therefore, the very norms by which one raises one’s status within a gang makes gang membership necessary for personal safety. Needless to say, most of the resulting mayhem is accomplished with guns. (Note 1/15/13: However, it would seem that, nationwide, only 12 percent of homicides are gang-related.)

Our misguided war on drugs is surely an important factor where gangs are concerned. This is another vicious circle: Like Prohibition before it, the war on drugs renders the sale of illicit drugs extraordinarily profitable while requiring that drug dealers function outside the law, protecting their investment and turf with guns. If we ended our war on drugs, the money that finances most gang activity would disappear, as would one of the primary reasons for gang violence. No doubt, gangs would remain, along with the other sources of violent crime. But with the war on drugs abandoned, our police, courts, and departments of corrections could focus on the real problem of violence.↩

[Added 1/4/13] In fact, a revolver can be reloaded even faster than that.↩

Of course, in many situations, even the best-trained guard would have no chance to draw his gun defensively, or would be unwise to do so. Picture the President of the United States moving through a crowd or delivering a speech: In the event of an assassination attempt, the job of his security detail is to immediately disrupt the shooter’s aim, bring him to the ground, and disarm him—and to get the president to safety. Drawing their weapons and returning fire, especially in a crowd, is not part of the plan. But the tactics appropriate to having a dozen guards protecting a high-risk target in a crowd do not extend to every situation involving an active shooter. And one can easily think of circumstances in which members of the Secret Service would need their guns.↩

Related Article:

December 24, 2012

The Moral Animal

November 11, 2012

Science on the Brink of Death

(Photo by h.koppdelaney)

One cannot travel far in spiritual circles without meeting people who are fascinated by the “near-death experience” (NDE). The phenomenon has been described as follows:

Frequently recurring features include feelings of peace and joy; a sense of being out of one’s body and watching events going on around one’s body and, occasionally, at some distant physical location; a cessation of pain; seeing a dark tunnel or void; seeing an unusually bright light, sometimes experienced as a “Being of Light” that radiates love and may speak or otherwise communicate with the person; encountering other beings, often deceased persons whom the experiencer recognizes; experiencing a revival of memories or even a full life review, sometimes accompanied by feelings of judgment; seeing some “other realm,” often of great beauty; sensing a barrier or border beyond which the person cannot go; and returning to the body, often reluctantly.

(E.F. Kelly et al., Irreducible Mind: Toward a Psychology for the 21st Century. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007, p. 372)

Such accounts have led many people to believe that consciousness must be independent of the brain. Unfortunately, these experiences vary across cultures, and no single feature is common to them all. One would think that if a nonphysical domain were truly being explored, some universal characteristics would stand out. Hindus and Christians would not substantially disagree—and one certainly wouldn’t expect the after-death state of South Indians to diverge from that of North Indians, as has been reported. It should also trouble NDE enthusiasts that only 10−20 percent of people who approach clinical death recall having any experience at all.

However, the deepest problem with drawing sweeping conclusions from the NDE is that those who have had one and subsequently talked about it did not actually die. In fact, many appear to have been in no real danger of dying. And those who have reported leaving their bodies during a true medical emergency—after cardiac arrest, for instance—did not suffer the complete loss of brain activity. Even in cases where the brain is alleged to have shut down, its activity must return if the subject is to survive and describe the experience. In such cases, there is generally no way to establish that the NDE occurred while the brain was offline.

Many students of the NDE claim that certain people have left their bodies and perceived the commotion surrounding their near death—the efforts of hospital staff to resuscitate them, details of surgery, the behavior of family members, etc. Certain subjects even say that they have learned facts while traveling beyond their bodies that would otherwise have been impossible to know—for instance, a secret told by a dead relative, the truth of which was later confirmed. Of course, reports of this kind seem especially vulnerable to self-deception, if not conscious fraud. There is another problem, however: Even if true, such phenomena might suggest only that the human mind possesses powers of extrasensory perception (e.g. clairvoyance or telepathy). This would be a very important discovery, but it wouldn’t demonstrate the survival of death. Why? Because unless we could know that a subject’s brain was not functioning when these impressions were formed, the involvement of the brain must be presumed.

What is needed to establish the mind’s independence from the brain is a case in which a person has an experience—of anything—without associated brain activity. From time to time, someone will claim that a specific NDE meets this criterion. One of the most celebrated cases in the literature involves a woman, Pam Reynolds, who underwent a procedure known as “hypothermic cardiac arrest,” in which her core body temperature was brought down to 60 degrees, her heart was stopped, and blood flow to her brain was suspended so that a large aneurysm in her basilar artery could be surgically repaired. Reynolds reports having had a classic NDE, complete with an awareness of the details of her surgery. Her story has several problems, however. The events in the world that Reynolds reports having perceived during her NDE occurred either before she was “clinically dead” or after blood circulation had been restored to her brain. In other words, despite the extraordinary details of the procedure, we have every reason to believe that Reynolds’s brain was functioning when she had her experiences. The case also wasn’t published until several years after it occurred, and its author, Dr. Michael Sabom, is a born-again Christian who had been working for decades to substantiate the otherworldly significance of the NDE. The possibility that experimenter bias, witness tampering, and false memories intruded into this best-of-all-recorded cases is excruciatingly obvious.

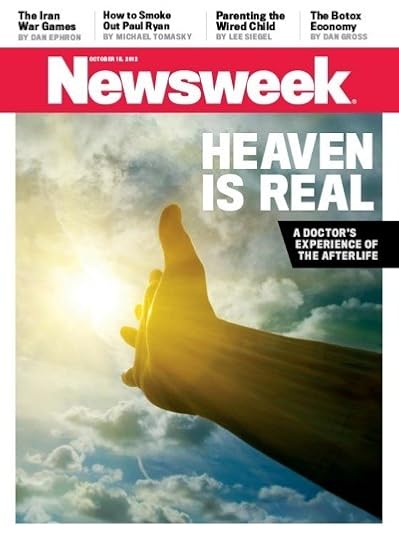

The latest NDE to receive wide acclaim was featured on the cover of Newsweek magazine. The great novelty of this case is that its subject, Dr. Eben Alexander, is a neurosurgeon who we might presume is competent to judge the scientific significance of his experience. His book on the subject, Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon’s Journey into the Afterlife, has landed atop the New York Times paperback best-seller list. As it happens, it displaced one of the best-selling books of the past decade, Heaven Is for Real—which is yet another account of the afterlife, based on the near-death adventures of a 4-year-old boy. Unsurprisingly, the two books offer incompatible views of what life is like beyond the prison of the brain. (As colorful as his account is, Alexander neglects to tell us that Jesus rides a rainbow-colored horse or that the souls of dead children must still do homework in heaven.)

Having now read Alexander’s book, I can say that it is every bit as remarkable as his Newsweek cover article suggested it would be. Unfortunately, it is not remarkable in the way that its author believes. I find that my original criticism of Alexander’s thinking can stand without revision. However, as he provides further “proof” of heaven in his book, there is more to say about the man’s mischief here on earth. There is also a rumor circulating online that, after attacking Alexander from the safety of my blog, I have refused to debate him in public. This is untrue. I merely declined the privilege of appearing with him on a parapsychology podcast, in the company of an irritating and unscrupulous host. I would be happy to have a public discussion with Alexander, should it ever seem worth doing.

As I wrote in my original article, the enthusiastic reception that Alexander is now enjoying suggests a general confusion about the nature of scientific authority. And much of the criticism I’ve received for dismissing his account has predictably focused on what appear to be the man’s impeccable scientific credentials. Certain readers feel that I have moved the goalposts: You see, even the testimony of a Harvard neurosurgeon isn’t good enough for a dogmatic, materialistic, fundamentalist atheist like Harris! And many people found the invidious distinction between a “neurosurgeon” and a “neuroscientist” (drawn in a comment by Mark Cohen in my last article) to be somewhat flabbergasting.

When debating the validity of evidence and arguments, the point is never that one person’s credentials trump another’s. Credentials just offer a rough indication of what a person is likely to know—or should know. If Alexander were drawing reasonable scientific conclusions from his experience, he wouldn’t need to be a neuroscientist to be taken seriously; he could be a philosopher—or a coal miner. But he simply isn’t thinking like a scientist—and so not even a string of Nobel prizes would shield him from criticism.

However, there are general differences between neurosurgeons and neuroscientists that might explain some of Alexander’s errors. The distinction in expertise is very easy to see when viewed from the other side: If the average neuroscientist were handed a drill and a scalpel and told to operate on a living person’s brain, the result would be horrific. From a scientific point of view, Alexander’s performance has been no prettier. He has surely killed the patient (in fact, he may have helped kill Newsweek, which announced that it would no longer publish a print edition immediately after his article ran), but the man won’t stop drilling. Many of his errors are glaring but immaterial: In his book, for instance, he understates the number of neurons in the human brain by a factor of 10. But others are absolutely damning to his case. Whatever his qualifications on paper, Alexander’s evangelizing about his experience in coma is so devoid of intellectual sobriety, not to mention rigor, that I would see no reason to engage with it—apart from the fact that his book seems destined to be read and believed by millions of people.

There are two paths toward establishing the scientific significance of the NDE: The first would be to show that a person’s brain was dead or otherwise inactive during the time he had an experience (whether veridical or not). The second would be to demonstrate that the subject had acquired knowledge about the world that could be explained only by the mind’s being independent of the brain (but again, it is hard to see how this can be convincingly done in the presence of brain activity).

In his Newsweek article, Alexander sought to travel the first path. Hence, his entire account hinged on the assertion that his cortex was “completely shut down” while he was seeing angels in heaven. Unfortunately, the evidence he has offered in support of this claim—in the article, in a subsequent response to my criticism of it, in his book, and in multiple interviews—suggests that he doesn’t understand what would constitute compelling evidence of cortical inactivity. The proof he offers is either fallacious (CT scans do not detect brain activity) or irrelevant (it does not matter, even slightly, that his form of meningitis was “astronomically rare”)—and no combination of fallacy and irrelevancy adds up to sound science. The impediment to taking Alexander’s claims seriously can be simply stated: There is absolutely no reason to believe that his cerebral cortex was inactive at the time he had his experience of the afterlife. The fact that Alexander thinks he has demonstrated otherwise—by continually emphasizing how sick he was, the infrequency of E. coli meningitis, and the ugliness of his initial CT scan—suggests a deliberate disregard of the most plausible interpretation of his experience. It is far more likely that some of his cortex was functioning, despite the profundity of his illness, than that he is justified in making the following claim:

My experience showed me that the death of the body and the brain are not the end of consciousness, that human experience continues beyond the grave. More important, it continues under the gaze of a God who loves and cares about each one of us, about where the universe itself and all the beings within it are ultimately going.

The very fact that Alexander remembers his NDE suggests that the cortical and subcortical structures necessary for memory formation were active at the time. How else could he recall the experience?

It would not surprise me, in fact, if Alexander were to claim that his memories are stored outside his brain—presumably somewhere between Lynchburg, Virginia, and heaven. Given that he is committed to proving the mind’s nonphysical basis, he holds a peculiar view of the brain’s operation:

[The brain] is a reducing valve or filter, shifting the larger, nonphysical consciousness that we possess in the nonphysical worlds down into a more limited capacity for the duration of our mortal lives.

There are some obvious problems with this—which anyone disposed to think like a neuroscientist would see. If the brain merely serves to limit human experience and understanding, one would expect most forms of brain damage to unmask extraordinary scientific, artistic, and spiritual insights—and, provided that a person’s language centers could be spared, the graver the injury the better. A few hammer blows or a well-placed bullet should render a person of even the shallowest intellect a spiritual genius. Is this the world we are living in?

In his book, Alexander also attempts to take the second path of proof—alleging that his NDE disclosed facts that could be explained only by the reality of life beyond the body. Most of these truths must be left to scientists of some future century to explore—for although his collision with the Mind of God seems to have fully slaked Alexander’s scientific curiosity, it apparently produced few insights that can be rendered in human speech. This puts the man in a difficult position as an educator:

I saw the abundance of life throughout countless universes, including some whose intelligence was advanced far beyond that of humanity. I saw that there are countless higher dimensions, but that the only way to know these dimensions is to enter and experience them directly. They cannot be known, or understood, from lower dimensional space. Cause and effect exist in these higher realms, but outside our earthly conception of them. The world of time and space in which we move in this terrestrial realm is tightly and intricately meshed within these higher worlds…. The knowledge given to me was not “taught” in the way that a history lesson or math theorem would be. Insights happened directly, rather than needing to be coaxed and absorbed. Knowledge was stored without memorization, instantly and for good. It didn’t fade, like ordinary information does, and to this day I still possess all of it, much more clearly than I possess the information that I gained over all my years in school.

Alexander claims undiminished knowledge of all this, and yet the only specifics he can produce on the page are as vapid as any ever published. And I suspect it is no accident that they have a distinctly Christian flavor. Here, according to Alexander, are the deepest truths he brought back to our world:

You are loved and cherished, dearly, forever. You have nothing to fear. There is nothing you can do wrong.

Not only will scientists be underwhelmed by these revelations, but Buddhists and students of Advaita Vedanta will find them astonishingly puerile. And the fact that Alexander returned from “the Core” of a loving cosmos only to piously assert the Christian line on evil and free will (“Evil was necessary because without it free will was impossible…”) renders the overall picture of his religious provincialism fairly indelible.

Happily, you do not need to read Alexander’s book to see him present what he considers the most compelling part of his case. You need only spend six minutes of your life in this world watching the following video:

Watch the video to the end. True, it will bring you six minutes closer to meeting your maker, but it will also teach you something about the limits of intellectual honesty. The footage shows Alexander responding to a question from Raymond Moody (the man who coined the term “near-death experience”). I am quite sure that I’ve never seen a scientist speak in a manner more suggestive of wishful thinking. If self-deception were an Olympic sport, this is how our most gifted athletes would appear when they were in peak condition.

It should also be clear that the knowledge of the afterlife that Alexander claims to possess depends upon some extraordinarily dubious methods of verification. While in his coma, he saw a beautiful girl riding beside him on the wing of a butterfly. We learn in his book that he developed his recollection of this experience over a period of months—writing, thinking about it, and mining it for new details. It would be hard to think of a better way to engineer a distortion of memory.

As you will know from watching the video, Alexander had a biological sister he never met, who died some years before his coma. Seeing her picture for the first time after his recovery, he judged this woman to be the girl who had joined him for the butterfly ride. He sought further confirmation of this by speaking with his biological family, from whom he learned that his dead sister had, indeed, always been “very loving.” QED.

As I said in my original response to his Newsweek article, I have spent much of my life studying and even seeking experiences of the kind Alexander describes. I haven’t contracted meningitis, thankfully, nor have I had an NDE, but I have experienced many phenomena that traditionally lead people to believe in the supernatural.

For instance, I once had an opportunity to study with the great Tibetan lama Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Nepal. Before making the trip, I had a dream in which he seemed to give me teachings about the nature of the mind. This dream struck me as interesting for two reasons: (1) The teachings I received were novel, useful, and convergent with what I later understood to be true; and (2) I had never met Khyentse Rinpoche, nor was I aware of having seen a photograph of him. This preceded my access to the Internet by at least five years, so the belief that I had never seen his picture was more plausible than it would be now. I also recall that I had no easy way of finding a picture of him for the sake of comparison. But because I was about to meet the man himself, it seemed that I would be able to confirm whether it had really been him in my dream.

First, the teachings: The lama in my dream began by asking who I was. I responded by telling him my name. Apparently, this wasn’t the answer he was looking for.

“Who are you?” he said again. He was now staring fixedly into my eyes and pointing at my face with an outstretched finger. I did not know what to say.

“Who are you?” he said again, continuing to point.

“Who are you?” he said a final time, but here he suddenly shifted his gaze and pointing finger, as though he were now addressing someone just to my left. The effect was quite startling, because I knew (insofar as one can be said to know anything in a dream) that we were alone. The lama was obviously pointing to someone who wasn’t there, and I suddenly noticed what I would later come to consider an important truth about the nature of the mind: Subjectively speaking, there is only consciousness and its contents; there is no inner self who is conscious. The feeling of being the experiencer of your experience, rather than identical to the totality of experience, is an illusion. The lama in my dream seemed to dissect this very feeling of being a self and, for a brief moment, removed it from my mind. I awoke convinced that I had glimpsed something quite profound.

After traveling to Nepal and encountering the arresting figure of Khyentse Rinpoche instructing hundreds of monks from atop a brocade throne, I was struck by the sense that he really did resemble the man in my dream. Even more apparent, however, was the fact that I couldn’t know whether this impression was accurate. Clearly, it would have been more fun to believe that something magical had occurred and that I had been singled out for some sort of transpersonal initiation—but the allure of this belief suggested only that the bar for proof should be raised rather than lowered. And even though I had no formal scientific training at that point, I knew that human memory is unreliable under conditions of this kind. How much stock could I put in the feeling of familiarity? Was I accurately recalling the face of a man I had met in a dream, or was I engaged in a creative reconstruction of it? If nothing else, the experience of déjà vu proves that one’s sense of having experienced something previously can jump the tracks of genuine recollection. My travels in spiritual circles had also brought me into contact with many people who seemed all too eager to deceive themselves about experiences of this kind, and I did not wish to emulate them. Given these considerations, I did not believe that Khyentse Rinpoche had really appeared in my dream. And I certainly would never have been tempted to use this experience as conclusive proof of the supernatural.

I invite the reader to compare this attitude to the one that Dr. Eben Alexander will likely exhibit before crowds of credulous people for the rest of his life. The structure of our experiences was similar—we were each given an opportunity to compare a face remembered from a dream/vision with a person (or photo) in the physical world. I realized that the task was hopeless. Alexander believes that he has made the greatest discovery in the history of science.

October 12, 2012

This Must Be Heaven

Once upon a time, a neurosurgeon named Eben Alexander contracted a bad case of bacterial meningitis and fell into a coma. While immobile in his hospital bed, he experienced visions of such intense beauty that they changed everything—not just for him, but for all of us, and for science as a whole. According to Newsweek, Alexander’s experience proves that consciousness is independent of the brain, that death is an illusion, and that an eternity of perfect splendor awaits us beyond the grave—complete with the usual angels, clouds, and departed relatives, but also butterflies and beautiful girls in peasant dress. Our current understanding of the mind “now lies broken at our feet”—for, as the doctor writes, “What happened to me destroyed it, and I intend to spend the rest of my life investigating the true nature of consciousness and making the fact that we are more, much more, than our physical brains as clear as I can, both to my fellow scientists and to people at large.”

Well, I intend to spend the rest of the morning sparing him the effort. Whether you read it online or hold the physical object in your hands, this issue of Newsweek is best viewed as an archaeological artifact that is certain to embarrass us in the eyes of future generations. Its existence surely says more about our time than the editors at the magazine meant to say—for the cover alone reveals the abasement and desperation of our journalism, the intellectual bankruptcy and resultant tenacity of faith-based religion, and our ubiquitous confusion about the nature of scientific authority. The article is the modern equivalent of a 14th-century woodcut depicting the work of alchemists, inquisitors, Crusaders, and fortune-tellers. I hope our descendants understand that at least some of us were blushing.

As many of you know, I am interested in “spiritual” experiences of the sort Alexander reports. Unlike many atheists, I don’t doubt the subjective phenomena themselves—that is, I don’t believe that everyone who claims to have seen an angel, or left his body in a trance, or become one with the universe, is lying or mentally ill. Indeed, I have had similar experiences myself in meditation, in lucid dreams (even while meditating in a lucid dream), and through the use of various psychedelics (in times gone by). I know that astonishing changes in the contents of consciousness are possible and can be psychologically transformative.

And, unlike many neuroscientists and philosophers, I remain agnostic on the question of how consciousness is related to the physical world. There are, of course, very good reasons to believe that it is an emergent property of brain activity, just as the rest of the human mind obviously is. But we know nothing about how such a miracle of emergence might occur. And if consciousness were, in fact, irreducible—or even separable from the brain in a way that would give comfort to Saint Augustine—my worldview would not be overturned. I know that we do not understand consciousness, and nothing that I think I know about the cosmos, or about the patent falsity of most religious beliefs, requires that I deny this. So, although I am an atheist who can be expected to be unforgiving of religious dogma, I am not reflexively hostile to claims of the sort Alexander has made. In principle, my mind is open. (It really is.)

But Alexander’s account is so bad—his reasoning so lazy and tendentious—that it would be beneath notice if not for the fact that it currently disgraces the cover of a major newsmagazine. Alexander is also releasing a book at the end of the month, Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon’s Journey into the Afterlife, which seems destined to become an instant bestseller. As much as I would like to simply ignore the unfolding travesty, it would be derelict of me to do so.

But first things first: You really must read Alexander’s article.

I trust that doing so has given you cause to worry that the good doctor is just another casualty of American-style Christianity—for though he claims to have been a nonbeliever before his adventures in coma, he presents the following self-portrait:

Although I considered myself a faithful Christian, I was so more in name than in actual belief. I didn’t begrudge those who wanted to believe that Jesus was more than simply a good man who had suffered at the hands of the world. I sympathized deeply with those who wanted to believe that there was a God somewhere out there who loved us unconditionally. In fact, I envied such people the security that those beliefs no doubt provided. But as a scientist, I simply knew better than to believe them myself.

What it means to be a “faithful Christian” without “actual belief” is not spelled out, but few nonbelievers will be surprised when our hero’s scientific skepticism proves no match for his religious conditioning. Most of us have been around this block often enough to know that many “former atheists”—like Francis Collins—spent so long on the brink of faith, and yearned for its emotional consolations with such vampiric intensity, that the slightest breeze would send them spinning into the abyss. For Collins, you may recall, all it took to establish the divinity of Jesus and the coming resurrection of the dead was the sight of a frozen waterfall. Alexander seems to have required a ride on a psychedelic butterfly. In either case, it’s not the perception of beauty we should begrudge but the utter absence of intellectual seriousness with which the author interprets it.

Everything—absolutely everything—in Alexander’s account rests on repeated assertions that his visions of heaven occurred while his cerebral cortex was “shut down,” “inactivated,” “completely shut down,” “totally offline,” and “stunned to complete inactivity.” The evidence he provides for this claim is not only inadequate—it suggests that he doesn’t know anything about the relevant brain science. Perhaps he has saved a more persuasive account for his book—though now that I’ve listened to an hour-long interview with him online, I very much doubt it. In his Newsweek article, Alexander asserts that the cessation of cortical activity was “clear from the severity and duration of my meningitis, and from the global cortical involvement documented by CT scans and neurological examinations.” To his editors, this presumably sounded like neuroscience.

The problem, however, is that “CT scans and neurological examinations” can’t determine neuronal inactivity—in the cortex or anywhere else. And Alexander makes no reference to functional data that might have been acquired by fMRI, PET, or EEG—nor does he seem to realize that only this sort of evidence could support his case. Obviously, the man’s cortex is functioning now—he has, after all, written a book—so whatever structural damage appeared on CT could not have been “global.” (Otherwise, he would be claiming that his entire cortex was destroyed and then grew back.) Coma is not associated with the complete cessation of cortical activity, in any case. And to my knowledge, almost no one thinks that consciousness is purely a matter of cortical activity. Alexander’s unwarranted assumptions are proliferating rather quickly. Why doesn’t he know these things? He is, after all, a neurosurgeon who survived a coma and now claims to be upending the scientific worldview on the basis of the fact that his cortex was totally quiescent at the precise moment he was enjoying the best day of his life in the company of angels. Even if his entire cortex had truly shut down (again, an incredible claim), how can he know that his visions didn’t occur in the minutes and hours during which its functions returned?

I confess that I found Alexander’s account so alarmingly unscientific that I began to worry that something had gone wrong with my own brain. So I sought the opinion of Mark Cohen, a pioneer in the field of neuroimaging who holds appointments in the Departments of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Science, Neurology, Psychology, Radiological Science, and Bioengineering at UCLA. (He was also my thesis advisor.) Here is part of what he had to say:

This poetic interpretation of his experience is not supported by evidence of any kind. As you correctly point out, coma does not equate to “inactivation of the cerebral cortex” or “higher-order brain functions totally offline” or “neurons of [my] cortex stunned into complete inactivity”. These describe brain death, a one hundred percent lethal condition. There are many excellent scholarly articles that discuss the definitions of coma. (For example: 1 & 2)

We are not privy to his EEG records, but high alpha activity is common in coma. Also common is “flat” EEG. The EEG can appear flat even in the presence of high activity, when that activity is not synchronous. For example, the EEG flattens in regions involved in direct task processing. This phenomenon is known as event-related desynchronization (hundreds of references).

As is obvious to you, this is truth by authority. Neurosurgeons, however, are rarely well-trained in brain function. Dr. Alexander cuts brains; he does not appear to study them. “There is no scientific explanation for the fact that while my body lay in coma, my mind—my conscious, inner self—was alive and well. While the neurons of my cortex were stunned to complete inactivity by the bacteria that had attacked them, my brain-free consciousness ...” True, science cannot explain brain-free consciousness. Of course, science cannot explain consciousness anyway. In this case, however, it would be parsimonious to reject the whole idea of consciousness in the absence of brain activity. Either his brain was active when he had these dreams, or they are a confabulation of whatever took place in his state of minimally conscious coma.

There are many reports of people remembering dream-like states while in medical coma. They lack consistency, of course, but there is nothing particularly unique in Dr. Alexander’s unfortunate episode.

Okay, so it appears that my own cortex hasn’t completely shut down. In fact, there are further problems with Alexander’s account. Not only does he appear ignorant of the relevant science, but he doesn’t realize how many people have experienced visions similar to his while their brains were operational. In his online interview we learn about the kinds of conversations he’s now having with skeptics:

I guess one could always argue, “Well, your brain was probably just barely able to ignite real consciousness and then it would flip back into a very diseased state,” which doesn’t make any sense to me. Especially because that hyper-real state is so indescribable and so crisp. It’s totally unlike any drug experience. A lot of people have come up to me and said, “Oh that sounds like a DMT experience,” or “That sounds like ketamine.” Not at all. That is not even in the right ballpark.

Those things do not explain the kind of clarity, the rich interactivity, the layer upon layer of understanding and of lessons taught by deceased loved ones and spiritual beings.

“Not even in the right ballpark”? His experience sounds so much like a DMT trip that we are not only in the right ballpark, we are talking about the stitching on the same ball. Here is Alexander’s description of the afterlife:

I was a speck on a beautiful butterfly wing; millions of other butterflies around us. We were flying through blooming flowers, blossoms on trees, and they were all coming out as we flew through them… [there were] waterfalls, pools of water, indescribable colors, and above there were these arcs of silver and gold light and beautiful hymns coming down from them. Indescribably gorgeous hymns. I later came to call them “angels,” those arcs of light in the sky. I think that word is probably fairly accurate….

Then we went out of this universe. I remember just seeing everything receding and initially I felt as if my awareness was in an infinite black void. It was very comforting but I could feel the extent of the infinity and that it was, as you would expect, impossible to put into words. I was there with that Divine presence that was not anything that I could visibly see and describe, and with a brilliant orb of light….

They said there were many things that they would show me, and they continued to do that. In fact, the whole higher-dimensional multiverse was this incredibly complex corrugated ball and all these lessons coming into me about it. Part of the lessons involved becoming all of what I was being shown. It was indescribable.

But then I would find myself—and time out there I can say is totally different from what we call time. There was access from out there to any part of our space/time and that made it difficult to understand a lot of these memories because we always try to sequence things and put them in linear form and description. That just really doesn’t work.

Everything that Alexander describes here and in his Newsweek article, including the parts I have left out, has been reported by DMT users. The similarity is uncanny. Here is how the late Terence McKenna described the prototypical DMT trance:

Under the influence of DMT, the world becomes an Arabian labyrinth, a palace, a more than possible Martian jewel, vast with motifs that flood the gaping mind with complex and wordless awe. Color and the sense of a reality-unlocking secret nearby pervade the experience. There is a sense of other times, and of one’s own infancy, and of wonder, wonder and more wonder. It is an audience with the alien nuncio. In the midst of this experience, apparently at the end of human history, guarding gates that seem surely to open on the howling maelstrom of the unspeakable emptiness between the stars, is the Aeon.