Sam Harris's Blog, page 23

August 31, 2013

The Moral Landscape Challenge

It has been nearly three years since The Moral Landscape was first published in English, and in that time it has been attacked by readers and nonreaders alike. Many seem to have judged from the resulting cacophony that the book’s central thesis was easily refuted. However, I have yet to encounter a substantial criticism that I feel was not adequately answered in the book itself (and in subsequent talks).

So I would like to issue a public challenge. Anyone who believes that my case for a scientific understanding of morality is mistaken is invited to prove it in 1,000 words or less. (You must refute the central argument of the book—not peripheral issues.) The best response will be published on this website, and its author will receive $1,000. If any essay actually persuades me, however, its author will receive $10,000, and I will publicly recant my view.

Submissions will be accepted here the week of February 2-9, 2014.

Note 9/1/13: A generous reader has made a matching pledge, so the prize money has now doubled to $2,000 and $20,000.

FAQ

1. You have said that these essays must attack the “central argument” of your book. What do you consider that to be?

Here it is: Morality and values depend on the existence of conscious minds—and specifically on the fact that such minds can experience various forms of well-being and suffering in this universe. Conscious minds and their states are natural phenomena, fully constrained by the laws of Nature (whatever these turn out to be in the end). Therefore, there must be right and wrong answers to questions of morality and values that potentially fall within the purview of science. On this view, some people and cultures will be right (to a greater or lesser degree), and some will be wrong, with respect to what they deem important in life.

You might want to read what I’ve already written in response to a few critics. (A version of this article became the Afterword to the paperback edition of The Moral Landscape.) I also recommend you watch the talk that I linked to above.

2. Can you give some guidance as to what you would consider a proper demolition of your thesis?

If you show that my “worst possible misery for everyone” argument fails, or that other branches of science are self-justifying in a way that a science of morality could never be, or that my analogy to a landscape of multiple peaks and valleys is fundamentally flawed, or that the fact/value distinction holds in a way that I haven’t yet understood—you stand a very good chance of torpedoing my argument and changing my mind.

3. What sort of criticism is likely to be ineffective?

You will definitely not win this prize if you fail to notice the distinction I make between finding answers in practice and there being answers in principle, if you define science in narrow terms to mean doing the former while wearing a white lab coat, if you imagine that my thesis entails that scientists are more moral than farmers and bricklayers, or if, like the philosopher Patricia Churchland, you do all of those things with an air of scornful pomposity appropriate to a Monty Python routine.

July 31, 2013

Free Will and the Reality of Love

(Photo by h.koppdelaney)

Many readers continue to express confusion—even outrage and anguish—over my position on free will. Some are convinced that my view is self-contradictory. Others are persuaded of its truth but find the truth upsetting. They say that if cutting through the illusion of free will undermines hatred, it must undermine love as well. They worry about a world in which we view ourselves and other people as robots. I have heard from readers struggling with clinical depression who find that reading my book Free Will, or my blog articles on the topic, has only added to their troubles. Perhaps there is more to say…

First, I’d like to address the common charge that it is simply self-contradictory to talk about the illusoriness of free will while using words such as “choice,” “intention,” “decision,” “deliberation,” and “effort.” If free will is an illusion, it would seem, these qualities of mind must be illusory as well. In one sense, this is true. It would perhaps be more precise to speak of “apparent choices.” But the distinction isn’t generally relevant at the level of our experience. In terms of experience, there is no contradiction between truth and appearance. Even in the absence of free will, I find that I can speak of choices, intentions, and efforts without hedging.

Consider the present moment from the point of view of my conscious mind: I have decided to write this blog post, and I am now writing it. I almost didn’t write it, however. In fact, I went back and forth about it: I feel that I’ve said more or less everything I have to say on the topic of free will and now worry about repeating myself. I started the post, and then set it aside. But after several more emails came in, I realized that I might be able to clarify a few points. Did I choose to be affected in this way? No. Some readers were urging me to comment on depressing developments in “the Arab Spring.” Others wanted me to write about the practice of meditation. At first I ignored all these voices and went back to working on my next book. Eventually, however, I returned to this blog post. Was that a choice? Well, in a conventional sense, yes. But my experience of making the choice did not include an awareness of its actual causes. Subjectively speaking, it is an absolute mystery to me why I am writing this.

My workflow may sound a little unconventional, but my experience of writing this article fully illustrates my view of free will. Thoughts and intentions arise; other thoughts and intentions arise in opposition. I want to sit down to write, but then I want something else—to exercise, perhaps. Which impulse will win? For the moment, I’m still writing, and there is no way for me to know why—because at other times I’ll think, “This is useless. I’m going to the gym,” and that thought will prove decisive. What finally causes the balance to swing? I cannot know subjectively—but I can be sure that electrochemical events in my brain decide the matter. I know that given the requisite stimulus (whether internal or external), I will leap up from my desk and suddenly find myself doing something else. As a matter of experience, therefore, I can take no credit for the fact that I got to the end of this paragraph.

But the apparent reality of choice remains intact. It isn’t wrong to say that I decided to write this post—and it certainly isn’t wrong to say that my writing it requires some conscious effort. I can’t write it by accident, or in my sleep. The writing itself is clearly the product of my unconscious mind—I cannot know, for instance, why one word or bit of syntax comes forward and another doesn’t—but the entire project requires consciousness to come into being. Certain things cannot be thought or done unless they are warmed by the light of conscious awareness. I am, after all, writing about what it is like to be me at this moment—and it would be like nothing to be me without consciousness.

What many people seem to be missing is the positive side of these truths. Seeing through the illusion of free will does not undercut the reality of love, for example—because loving other people is not a matter of fixating on the underlying causes of their behavior. Rather, it is a matter of caring about them as people and enjoying their company. We want those we love to be happy, and we want to feel the way we feel in their presence. The difference between happiness and suffering does not depend on free will—indeed, it has no logical relationship to it (but then, nothing does, because the very idea of free will makes no sense). In loving others, and in seeking happiness ourselves, we are primarily concerned with the character of conscious experience.

Hatred, however, is powerfully governed by the illusion that those we hate could (and should) behave differently. We don’t hate storms, avalanches, mosquitoes, or flu. We might use the term “hatred” to describe our aversion to the suffering these things cause us—but we are prone to hate other human beings in a very different sense. True hatred requires that we view our enemy as the ultimate author of his thoughts and actions. Love demands only that we care about our friends and find happiness in their company. It may be hard to see this truth at first, but I encourage everyone to keep looking. It is one of the more beautiful asymmetries to be found anywhere.

June 9, 2013

Islam and the Misuses of Ecstasy

(Photo by Camera Eye)

I have long struggled to understand how smart, well-educated liberals can fail to perceive the unique dangers of Islam. In The End of Faith, I argued that such people don’t know what it’s like to really believe in God or Paradise—and hence imagine that no one else actually does. The symptoms of this blindness can be quite shocking. For instance, I once ran into the anthropologist Scott Atran after he had delivered one of his preening and delusional lectures on the origins of jihadist terrorism. According to Atran, people who decapitate journalists, filmmakers, and aid workers to cries of “Alahu akbar!” or blow themselves up in crowds of innocents are led to misbehave this way not because of their deeply held beliefs about jihad and martyrdom but because of their experience of male bonding in soccer clubs and barbershops. (Really.) So I asked Atran directly:

“Are you saying that no Muslim suicide bomber has ever blown himself up with the expectation of getting into Paradise?”

“Yes,” he said, “that’s what I’m saying. No one believes in Paradise.”

At a moment like this, it is impossible to know whether one is in the presence of mental illness or a terminal case of intellectual dishonesty. Atran’s belief—apparently shared by many people—is so at odds with what can be reasonably understood from the statements and actions of jihadists that it admits of no response. The notion that no one believes in Paradise is far crazier than a belief in Paradise.

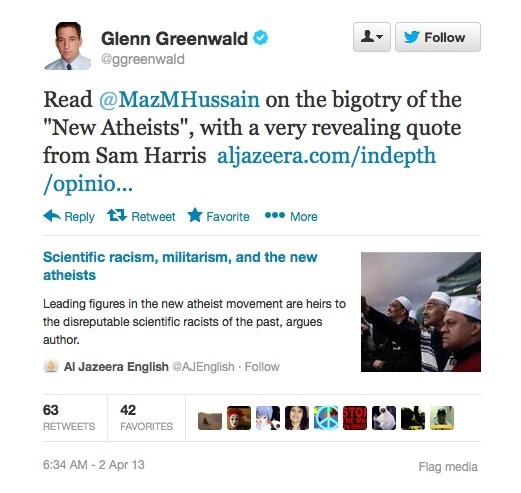

But there are deeper ironies to be found here. Whenever I criticize Islam, I am attacked for my purported failure to empathize with Muslims throughout the world—both the peaceful billion, who are blameless, and the radicals, whose legitimate political grievances and social ties cause them to act out in regrettable ways. Consider this standard calumny from Glenn Greenwald:

How anyone can read any of these passages and object to claims that Harris’ worldview is grounded in deep anti-Muslim animus is staggering. He is at least as tribal, jingoistic, and provincial as those he condemns for those human failings, as he constantly hails the nobility of his side while demeaning those Others.

The irony is that it is the secular liberals like Greenwald who are lacking in empathy. As I have pointed out many times before, they fail to empathize with the primary victims of Islam—the millions of Muslim women, freethinkers, homosexuals, and apostates who suffer most under the taboos and delusions of this faith. But secular liberals also fail to understand and empathize with the devout.

Let us see where the path of empathy actually leads…

First, by way of putting my own empathy on my sleeve, let me say a few things that will most likely surprise many of my readers. Despite my antipathy for the doctrine of Islam, I think the Muslim call to prayer is one of the most beautiful sounds on earth. Take a moment to listen:

I find this ritual deeply moving—and I am prepared to say that if you don’t, you are missing something. At a minimum, you are failing to understand how devout Muslims feel when they hear this. I think everything about the call to prayer is glorious—apart from the fact that, judging by the contents of the Koran, the God we are being asked to supplicate is evil and almost surely fictional. Nevertheless, if this same mode of worship were directed at the beauty of the cosmos and the mystery of consciousness, few things would please me more than a minaret at dawn.

I also love the poetry of Rumi, and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan is one of my favorite musicians of all time. True, both of these men were Sufis—and Sufism is reviled as heresy throughout much of the Muslim world. But I expect that many of the people who attack me as an anti-Muslim bigot will be surprised to learn that I love these products of (nominally) Muslim religious devotion more than most other forms of art. If you have never heard Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, you owe it to yourself to listen:

I also have no problem with spiritual devotion, ecstasy, and awe—in fact, I think they are among the most important experiences a human being can have. I just object to the incredible ideas that surround such experiences in every church, synagogue, and mosque. I also worry that certain religious beliefs make devotion, ecstasy, and awe both divisive and dangerous. Again, my tolerance for difference is much higher than my critics understand. I’m not a scared white guy who is put off by the howls of the natives. In fact, I’ve done a fair amount of howling with the natives myself. I know what these people are experiencing, and I value many of the same experiences.

To see the world through my eyes—or to realize why you do not—watch at least a few minutes of each of the following videos.

I know that many readers will view the scene depicted above as an example of disturbingly irrational, mob behavior. Are these people crazy? No. These are Turkish Sufis chanting the Zikr. I have done this practice—not in such a crowded and colorful context—but I understand what these people are up to from the inside. And I know contemplative rituals of this kind can be extremely rewarding. Here’s another example, of a sort more reminiscent of my own experience:

I find this sort of chanting beautiful—and I know how good it feels to do it for hours at a stretch, even all night. Here is the practice in a Hindu context:

It is true that I’m more comfortable with what the Hindus are doing here, because they are expressing their devotion to God in the form of a Divine Lover, and their feelings of religious ecstasy are explicitly channeled in that direction. There is no evidence that Lord Krishna exists, of course, but we needn’t worry about whether any of these people are fans of global jihad.

Unlike many of my critics, I recognize that these practices profoundly affect people. In fact, I’ve spent thousands of hours doing practices of this kind. I am not even slightly scared of “the Other.” I love the Other—I love his food, music, and architecture, and I even share his spiritual concerns. That is why when I see something like this, I fear for the future of civilization:

Watch the entire video with your full attention. If you cannot feel the haunting beauty of this recitation, if it is inexplicable to you that people can be moved to tears by the mere sound of these verses, then you are not in contact with the data. Indeed, if you don’t understand how someone could be willing to die to defend the legitimacy of such an experience, you are very poorly placed to understand the problem of Islam.

This video has everything: the power of ritual and the power of the crowd; tears of devotion and a lust for vengeance. How many of the people in that mosque are jihadists? I have no idea—perhaps none. But their spiritual aspirations and deepest positive emotions—love, devotion, compassion, bliss, awe—are being focused through the lens of sectarian hatred and humiliation. Read every word of the translation so that you understand what these devout people are weeping over. Their ecstasy is inseparable from the desire to see nonbelievers punished in hellfire. Is this some weird distortion of the true teachings of Islam? No. This is a recitation from the Koran articulating its central message. The video has over 2 million views on YouTube. It was posted by someone who promised his fellow Muslims that they, too, would weep tears of devotion upon seeing it. The reciter is Sheikh Mishary bin Rashid Alafasy of Kuwait. He has as many Twitter followers as Jerry Seinfeld and J.K. Rowling (2 million). In doctrinal terms, this is not the fringe of Islam. It is the center.

Islam marries religious ecstasy and sectarian hatred in a way that other religions do not. Secular liberals who worry more about “Islamophobia” than about the actual doctrine of Islam are guilty of a failure of empathy. They fail not just with respect to the experience of innocent Muslims who are treated like slaves and criminals by this religion, but with respect to the inner lives of its true believers. Most secular people cannot begin to imagine what a (truly) devout Muslim feels. They are blind to the range of experiences that would cause an otherwise intelligent and psychologically healthy person to say, “I will happily die for this.” Unless you have tasted religious ecstasy, you cannot understand the danger of its being pointed in the wrong direction.

April 29, 2013

Twitter Q&A 4/29/13: #AskSamAnything

(Photo by Sprengben)

I will take your questions from 6-7pm (Eastern), Monday 4/29. Please use the Twitter hashtag #AskSamAnything to participate.

Possible topics include: the mind/brain, science v. religion, free will, moral truth, meditation, terrorism, consciousness, gurus and cults, publishing, lying, etc.

Note: If you are following the conversation live, you will need to keep refreshing your browser to watch it develop.

* * *

Joe Goodrich @josephgoodrich Thoughts on Islam and the Boston Bombing—and the press’ reaction to (avoidance of) the Islam connection?

This is probably worthy of a separate blog post. But, briefly, I have noticed a persistent failure to differentiate four general types of bad actor: (1) psychotics or people who suffer some obvious form of mental illness (e.g. Jared Loughner, James Holmes, Adam Lanza), (2) psychopaths or those whom we would generally describe as classically “evil” (e.g. most serial killers, Kim Jong Il), (3) psychologically normal people who do bad things because they are a part of a bad system or have poorly aligned incentives (e.g. many gang members, most soldiers fighting in unjust wars, certain business people), and (4) otherwise normal people who are captivated by some transcendent, divisive ideas. Some of these belief systems are merely political, or otherwise secular, in that their goals are exclusively a matter of bringing about specific changes in this world. But the worst are religious—whether or not they are attached to mainstream religion—in that they are energized by beliefs about otherworldly rewards and punishments, prophecies, magic, etc.

Obviously, a person can belong to all four types at once and have his antisocial behavior overdetermined. Someone can be both a psychotic and a psychopath, part of a corrupt system, and devoted to a dangerous, transcendent cause. But there are many examples of each type in its pure form. At the moment, I see no reason to think that the Boston Marathon bombers were anything but type (4)—which puts all the onus on their religious beliefs. And anyone who puts them in the same category as Jared Loughner and Adam Lanza, as many commentators have, is guilty of obscurantism. “Why are angry, disaffected men so prone to violence?” Wrong question.

Mark B @emexbe What’s your opinion of panpsychism? A technically valid theory or scientifically impossible?

Possibly true, but probably unfalsifiable—and, therefore, probably vacuous in scientific terms. Is the sun conscious? There’s no reason to think so, but would I expect the sun to behave differently if its processes of nuclear fusion were associated with subjectivity? No. So, even if panpsychism were true, I would expect it to be undetectable.

Adam Dorr @adam_dorr You seem to avoid political morality. Care to engage? Is conservativism inherently less moral than liberalism?

I touch on this briefly in The Moral Landscape and Free Will. These views have different strengths and weaknesses. Depending on the context, one can be less in touch with reality than the other and conducive to greater harm. One of the virtues of liberalism is self-doubt and a willingness to consider the other person’s point of view. In the presence of antagonists who don’t have a point of view worth considering (e.g. psychopaths, religious maniacs), liberalism can be a recipe for masochism and moral cowardice. Conservatives tend not have this problem. But when conservatives are wrong, they often lack the corrective mechanisms of liberals. It’s hard to generalize, but it is worth noting that there is a structural asymmetry here: liberalism can be exploited in a way that conservatism cannot.

Mark B @emexbe Have you and @danieldennett ever considered having a public debate about free will?

Yes, we are planning on it. But I can’t yet say when it will happen.

Tiny Klout Flag14joseph morris @josephlmorris Do you think that truth has value in and of itself or is its value derived from its affect on well-being

This is actually a very subtle question—and my answer is pretty easy to misconstrue. But I think that (ultimately, when we get very clear about what we mean by these terms) truth is a slave to well-being. Which is to say that anything you can say about the value of knowing the truth (e.g. it’s so interesting, so useful, so beautiful, etc.) translates into a claim about the well-being of conscious creatures.

Oliver Rees Brown @degodier How best to publish 1st book 4students my age on Humanism based on 4horsemen’s combined work+Pinker+much more

Please see my article, How to Get Your Book Published in 6 (Painful) Steps.

TimSkinner @_timskinner Is there a good strategy to help counter blasphemy laws endangering our international secular counterparts?

We need to blaspheme wherever necessary, publicly and without apology, criticize anyone who takes offense—and ridicule those who pretend to take offense.

Glenn the Technomage @bluedream Are you planning on writing a book exploring spirituality without superstition?

Yes, that’s my next book. The manuscript is due in a month (as you can see, I’m procrastinating). It will be out next year.

Anton Vikström @Anton_Vikstrom How square the “illusion of the self” with, in meditation, simply *observing* the stream of thoughts?

If you observe the stream of thoughts closely enough, you will see that there is no self doing the observing.

Alan Litchfield @MalcontentsGamb How can you establish that there are moral facts to be known? Can you give us an example (or two) of a moral fact.

It is a fact that this universe admits of an extraordinary range of pleasant an unpleasant experiences for conscious creatures. It is also a fact that movement in this space is constrained by the laws of nature (whatever they turn out to be). Forget, for a moment, that you ever heard the word “morality.” Just admit that we have a navigation problem on our hands: If we go too far in one direction, things reliably get very unpleasant (and not the kind of unpleasant that has a silver lining); go in another, and everyone gets really happy, creative, fulfilled, etc. These differences exist and movement is possible. Now let’s recall this word “morality”: if you don’t think that it would be immoral to move everyone downward into hell, or moral to move them upward in collective flourishing, I don’t know what you’re talking about.

Bryan Goodrich @bryangoodrich Morality is about brain states, how does this apply to ethics of future people (e.g. genetic manip, unborn) or the environ?

I wouldn’t say that morality is about “brain states”—I would say that it relates to the actual and possible states of conscious minds. So if computers of the future become conscious, they will be part of the moral landscape.

The question of our ethical connection to the unborn and to the never-to-be born is an interesting one. We clearly must place some value on possible states of suffering and well-being. For instance, why would it be bad to painlessly kill every person currently alive in his or her sleep? We can’t say it would be bad because of all the suffering it would cause—because everyone would die painlessly and there would be no one left to grieve. The immorality must relate to the potential states of future happiness that would be cut off by such an act. If you believe, as I do, that human life is, on balance, extraordinarily beautiful and well worth living, you must think that ending all human life would be bad, even if it could be done painlessly.

In my view, the value of the environment is reducible to the value it has for all the conscious creatures in it (both actual and potential). For a rock or a stream to be valuable, I think it must be valuable to some actual or possible creature. This doesn’t require that the creature be aware of this value—you and I surely have compounds in our bodies that are absolutely integral to our physical and mental well-being that science has not yet discovered. But value must matter to someone, somewhere, somehow—at least potentially.

Robert Bauer @RobertBauer18 Do you think that people like Chomsky and Greenwald actually believe their own myopic views?

I’m prepared to give them the benefit of the doubt.

peter walsh @speciesisminart Moral Landscape says value the well being of conscious creatures - only to solely focus on humans. Why?

My argument applies to all conscious creatures, to the extent that they are conscious. I focus on humans because we are most concerned about ourselves, and I believe we are right to be, given that we seem to experience the widest range of conscious states. But I do think we should be very concerned about the suffering we impose on other animals—and brain-to-body ratio seems a reasonable basis upon which to organize our intuitions on this front (e.g. we should be more concerned about chimps than about chickens).

Adam Simoneau @AyJaySimon To what extent do you agree w/ S. Levitt’s assertion that no proposed gun control measures will do much good?

I basically agree with Levitt about this. You can listen to his discussion of gun policy here.

Jakub Kuźmiński @AeternitasManet What did you learn from Christopher Hitchens?

One thing he taught me is that there are times when outrage is the only appropriate emotion—and not to express it at such moments is a moral failing.

Jefferson Grizzard @JeffGrizza Does your stance regarding free will affect your actions from day to day, or are its implications strictly societal?

My view about the illusoriness of free will makes it easy to let go of anger/hatred. I occasionally get angry, of course. There are people who behave in ways that I find despicable. But I can (ultimately) see their behavior as impersonal—even when it is directed at me personally. That doesn’t mean that I suddenly become trusting of everyone. I know that certain people can be counted upon to misbehave. But so can grizzly bears. We can fear grizzly bears and take steps to protect ourselves from them, but it makes no sense to hate them.

Jefferson Grizzard @JeffGrizza If the self is an illusion, who or what is witnessing that illusion?

Consciousness.

Anjo Bacarisas PA @JoBacarisas How do you define the secular spirituality?

Self-transcendence without divisive bullshit.

John Snow @JohnSno40182901 What are your thoughts on Sufism?

It’s a myth that there have been no intolerant Sufis. But Sufism, being the mystical tradition within Islam, has tended to be more benign and far more interesting than the religion itself. I have always loved the poetry of Rumi and the music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. I have practiced with Sufis, and I have no doubt that people have interesting insights and experiences chanting the Zikr, for instance. But insofar as these insights are interesting, they will be unintelligible in light of the Koran.

Andy French @andyfrenchie If we live in a multiverse and causality unfolds in all directions, how can we morally justify one action versus another ?

Well, if you share the hope that you live in one of the universes where you don’t suffer unnecessarily, you might want to act accordingly.

Anti Life EFIList Ⓥ @AntiLifeEFIL Is is not objectively better never to have been? What flaw is there in the nonexistent state?

It is impossible to eat pancakes there.

Tiny Klout Flag12Usman Mian @UsmanMianMD Have u had many former Muslims credit you for being instrumental in their apostasy? I’m one!

Glad to hear it! I can’t say “many”—certainly not when compared to the numbers of Christians—but I do hear from them occasionally. I think this says more about the demographics of my readers than about specific religions.

Phil Myth @philmyth Have recently started exploring libertarianism and am wondering what your views on it are?

Again, labels can be misleading, but I’m a “libertarian” in the sense that I think that whatever can best be done in the private sector should be. And I believe that peaceful and honest people have the right to be left alone. Libertarianism rests on the acknowledgment that behind every law and every tax stands a loaded gun—i.e. if you don’t follow the law or pay the tax, men with guns will eventually show up at your door and haul you away to prison. Like most libertarians, I believe that the State should use such powers of coercion sparingly. Consenting adults should be able to do more or less anything they want (as long as they don’t harm others), and there is no such thing as a “victimless crime.” But I tend to break with libertarians on the following points: I believe that (1) certain important things cannot be accomplished by free markets (or cannot be best accomplished there); (2) too much wealth inequality is profoundly undesirable; and (3) Ayn Rand should be ignored.

Tony Earle @EarleTony From your pojnt of view, what would be the 3 main reasons why religion is deleterious for people…

1. It is false.

2. It is intrinsically divisive (because it is false and, therefore, provides a very poor basis for agreement).

3. It gives people bad reasons to be good, where good reasons are available.

Mike Anas @MikeAnas What are the merits of silent & introspective mindfulness vs. mindful walking, eating, or other forms of focused attention?

They’re ultimately the same. But it can be easier to first learn mindfulness as a sitting practice. I didn’t discover that walking meditation was as powerful as sitting until about midway through my first 10-day retreat.

Olsonic @BruinsScience Curious about your thoughts on the responsibilities of your fans to defend you from unscrupulous media attacks. nota1manjob?

Thanks for asking. I don’t think “responsibility” is the word I’d use—but I would be very grateful if readers would direct people to my Response to Controversy page whenever they see someone distorting my views online.

Mark Lambert @bootjangler11 What would it take to have a President of the US who was not afraid to declare his atheism or at least non-belief?

At least a dozen national polls showing that 60 percent of the population would happily vote for such a person. It will happen, but I doubt it will be in 2016.

Felix Berglund @Felix_Berglund Is it wrong to lie in negotiations?

The question more or less answers itself the moment you consider doing business with the same people again.

Adam5365 @Adam5365 What truly separates a pure conservative / true liberal as I (non party con) relate to most of your ideas

Interesting question—and it is one that is getting harder to answer. Obviously, it depends on whether a person is a social or fiscal conservative (or both), because the former position tends to depend on (unwarranted) religious beliefs. Generally speaking, if you think homosexuals should be free to marry and billionaires should admit that their wealth arises out of conditions that they did not create (political stability, good infrastructure, educated consumers, etc.), you are probably a “liberal” who will align with me on most questions—that is, until I tell you that Islam is more threatening than Anglicanism and that a person can be a responsible gun owner. Then you’ll call me a bigot and an NRA shill.

Nathan Edmondson @EdmondsonNathan Is it fair to divorce the valuable practices of Buddhism from Buddhism? Theravada for example.

Yes. Just as it’s fair to take the crackers and wine from Catholicism

Bête Politique @betepolitique Did Bruce Schneier convince you that racial profiling at airports was not a good idea?

You mean “profiling” (not “racial profiling”). No, he didn’t. Profiling is just another name for making judgments about people based on all of the statistical information we have available (and, no, it’s not another name for “bigotry”). We have limited resources to devote to security: The question is, should we allow highly trained people to use these resources intelligently, or should they be obliged to shine the spotlight of their attention at random? Granted, we don’t currently have highly trained screeners at the TSA, but we should. And the truth is, even untrained people are better at spotting potential terrorists than Schneier admits. In fact, most of us are better at noticing threatening people than we are at almost anything else we do—courtesy of evolution. I’m not arguing that we should give free rein to our latent xenophobia, but it is simply crazy to think that we can’t form fast, valid intuitions about the likelihood that a given person is about to kill everyone in sight, including himself. Again, my argument for profiling is really an argument for anti-profiling—that is, we shouldn’t waste time patting down people who stand no reasonable chance of being jihadists.

I agree with Schneier that random screening can play an important role in certain contexts, but it shouldn’t be motivated by political correctness. And I maintain that obviously wasting our security resources—as we do—is tantamount to putting innocent lives at risk. I say more about why I wasn’t convinced by Schneier here.

Otto Olah @ottoolah Hi @SamHarrisOrg, did you ever write about why not supporting the death penalty? I love your work!

Thanks. I haven’t written about my opposition to the death penalty at length—but my reasons can be gleaned from the general argument I present in Free Will.

mykamakiri @mykamakiri1 What is the best meditation exercise to try for a curious beginner who wants to get a taste of its benefits?

If you have never meditated before, I highly recommend that you start with a practice called vipassana. I discuss it here: How to Meditate.

Nicholas Phillips @zenmindz Is Vipassana different from Dzogchen? I find Vipassana often includes duality, and Dzogchen is non-dual.

Yes. The main difference is that you can start practicing vipassana from wherever you are—it’s a technique that anyone can learn. Dzogchen requires that you be able to recognize the intrinsic selflessness of consciousness (i.e. that you cut through the illusion that there is a thinker of your thoughts and an inner experiencer of your experience). So you can’t start Dzogchen until you can observe that consciousness, prior to thought, doesn’t feel like “I”—and the practice is nothing other than noticing this, again and again. I think vipassana is the perfect preliminary practice for Dzogchen.

Rasmus Pettersson @RasmusP When’s your new book coming out?

It is currently scheduled for June 2014.

Fredrik Eggen @fredrikeggen Why isn’t the argument ‘atheist dictators did not commit their deeds in the name of atheism’ used more often?

I use it a lot, but the point bears repeating: I don’t hold religion accountable for all the bad things that religious people have done. I hold it accountable for all the bad things they have done because of their religious beliefs. No doubt, there are atheists and secularists who have caused immense amounts of human suffering, but I know of no cases in which they did this because they valued empirical evidence over faith or found specific religious doctrines irrational. As I’ve said on more than one occasion, no human society has ever suffered because its people became too reasonable.

Jens Kjær Jensen @JensKjrJensen If, as you say, science is to be the main arbiter of morality, do you still see a useful role for philosophy in this area?

I wouldn’t separate them. Our truth claims should be guided by reason and evidence. There is no clear line between (good) philosophy and science.

Sam Edwards @SamuelJEdwards How to find high quality meditation instruction that isn’t mired in dogma? Buddhism and Vipassana seem just as guilty.

It’s difficult. But in most contexts the dogma have no consequence. You can start practicing vipassana, for instance, without believing anything magical or superstitious. One can’t begin praying to Jesus that way.

Douglas Borg @doug_borg Some critics of A Moral Landscape say you do not addressing the is/ought problem. Are the critics missing your point?

Yes. I believe I have shown it to be a false problem (i.e. based on confusion). My critics continue to insist that I haven’t solved this false problem in the terms of their confusion. This is annoying and sends me sliding down the slopes of the moral landscape.

April 25, 2013

What Martial Arts Have to Do With Atheism

April 20, 2013

The Straight Path

(Photo by PhillipC)

As I wrote in the introduction to Lying, Ronald A. Howard was one of my favorite professors in college, and his courses on ethics, social systems, and decision making did much to shape my views on these topics. Last week, he was kind enough to speak with me at length about the ethics of lying. The following post is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Ronald A. Howard directs teaching and research in the Decision Analysis Program of the Department of Management Science and Engineering at Stanford University. He is also the Director of the Department’s Decisions and Ethics Center, which examines the efficacy and ethics of social arrangements. He defined the profession of decision analysis in 1964 and has since supervised several doctoral theses in decision analysis every year. His experience includes dozens of decision analysis projects that range over virtually all fields of application, from investment planning to research strategy, and from hurricane seeding to nuclear waste isolation. He was a founding Director and Chairman of Strategic Decisions Group and is President of the Decision Education Foundation, an organization dedicated to bringing decision skills to youth. He is a member of the National Academy of Engineering, a Fellow of INFORMS and IEEE, and the 1986 Ramsey medalist of the Decision Analysis Society. He is the author, with Clint Korver, of Ethics for the Real World: Creating a Personal Code to Guide Decisions in Work and Life.

Harris: First, let me say that I greatly appreciate your taking the time to do this interview. As you may or may not know, your courses on ethics at Stanford were pivotal in my moral and intellectual development—as they have surely been for many others. So it’s an honor to be able to bring your voice to my readers.

Howard: My pleasure.

Harris: Let’s talk about lying. I think we might as well start with the hardest case for the truth-teller: The Nazis are at the door, and you’ve got Anne Frank hiding in the attic. How do you think about situations in which honesty seems to open the door—in this case literally—to moral catastrophe?

Howard: As you point out, these are very difficult situations to think through, and one hopes that one would be able to transform them. In other words, if you were the Buddha or some other remarkable person, perhaps some version of the truth could still save the day. You probably remember the story of the Buddha encountering a murderer who had killed 1,000 people. Instead of avoiding him, he said, “I know you’re going to kill me, but would you first cut off the large branch on that tree?” The murderer does so, and then the Buddha says, “Thank you. Now would you put it back on?” And—the story goes—the murderer suddenly realized that he was playing the wrong game in life, became enlightened, and a monk.

It’s not inconceivable that one could transform even a terribly dire situation—and I think that doing so would constitute a kind of moral perfection. Of course, that’s pretty hard to imagine for most of us when confronted by Nazis at the door. But there are extreme cases in which, depending on the participants, it’s not clear that telling the truth will always lead to a bad outcome.

Harris: I agree. But it’s probably setting the bar too high for most of us, most of the time—and, more important, it is surely setting it too high for any randomly selected group of Nazis. It seems that there are situations in which one must admit at the outset that one is not in the presence of an ethical intelligence that can be reasoned with.

I take your point, however, that if one makes this determination—i.e. these are not Nazis I’m going to be able to enlighten—one has closed the door to certain kinds of moral breakthroughs. For instance, I remember hearing about a rabbi who was receiving threatening calls from a white supremacist. Rather than hang up or call the police, the rabbi patiently heard the man out, every time he called, whatever the hour. Eventually they started having a real conversation, and ultimately the rabbi broke through, and the white supremacist started telling him about all the troubles in his life. They even met and became friends. One certainly likes to believe that such breakthroughs are possible.

Nevertheless, in some situations the threat is so obvious, and the time in which one has to make a judgment so brief, that one must err on the side of treating an avowed enemy as a real enemy.

Howard: Of course. And some people deal with this by thinking in a kind of a hierarchy. They might say, “Well, I don’t want to kill people, but I’ll kill in self-defense. I don’t want to steal but I’d steal to keep someone alive. I wouldn’t ordinarily lie, but I’ll do it to save someone’s property or to save a life, and so forth. That’s another way to handle it.

Harris: That is the way I handled it in my book. Essentially, I view lying in these cases as an extension of the continuum of force one would use against a person who no longer appears to be capable of a rational conversation. If you would be willing to defensively shoot a person who had come to harm you or someone in your care, or you would be willing to punch him in the jaw, it seems ethical to use even less force—that is, mere speech—to deflect his bad intentions.

Howard: I think that’s a very practical kind of engineering solution. We are beginning to speak here about the part of one’s ethical code that one is willing to impose on other people, which I refer to by the maxim “Peaceful, honest people have the right to be left alone.” It simplifies things to ask, “What if someone violates this maxim and, therefore, is not behaving in ways that I would like people to behave, leaving innocent people alone, and so forth?” Then, I reserve the right of self-defense. If someone is trying to kill me, I’m going to use the minimum effective force necessary to stop him. I read your article on this, and I agree with you completely.

The next level is stealing: Needless to say, if I could steal a weapon from someone who was about to kill me, that would be fine. And if I couldn’t transform the situation as some more enlightened person might—into a real circumstance of teaching—then I would lie. I would use the minimum distortion necessary to get the problem to go away.

At one end of the spectrum, you can be super-optimistic about people. But let’s face it, there are people who are up to no good in all kinds of ways. I’m not going to abet them in violating other people’s right to be left alone, and I’ll do whatever is necessary to avoid that.

Harris: Obviously, the Anne Frank case doesn’t often arise in the ordinary course of life, but there are many other troubling situations in which people find it tempting to lie. When I asked for feedback from readers on the first edition of Lying, I received many accounts in which people found themselves lying for reasons that they thought entirely noble. One case I’d like you to reflect on relates to a terminally ill child.

Your child doesn’t have long to live. Naturally, he has questions about when he will die and about what happens after death. Let’s say that, based on what your doctor has said, you think that your child has about two months to live. You also believe that everyone gets a dial tone after death and that you’ll never see each other again. It seems hard to avoid the conclusion that giving a false but consoling response to his questions could make your child’s last two months of life happier than they would otherwise be.

Howard: Well, that’s a case where I would take a much stronger position. I’ve had people in my classes who regularly deal with the dying, and their advice is always the same: You should tell the truth as you believe it to be. The important thing to determine is, what is the truth? So you ask the doctor, “Doctor, how long has he got?” and the truthful answer might be, “Well, you know some people surprise us, some people go quicker. We really can’t tell you exactly how long. Most people have two months but a few live longer, and so on.” Now, that’s the truth. If you say, “Oh, no, you’re going to recover,” when he’s probably going to die in a few months, you would deprive the person of the opportunity to do all those things that he or she might want to do in this limited time. In most cases, they know they’re dying. Let them go peacefully.

Once, a man in a group meeting shared that his young son was terminally ill. He said, “You know, it’s really sad: When he colors pictures, he uses only the black crayons.” Then, after one week, he spoke to the group again. He said, “You know what? I realized that I was holding myself back from my son because I was going to miss him so much after he dies.” He shared that truth with his son, telling him, “I love you so much, and I’m going to miss you.” And guess what? He reported that the boy was now using all the colors.

My understanding from people who deal with kids who are dying is that they know. The parents are really grieving for all the experiences that they’re not going to have with their child. The child isn’t thinking, “I’m not going to get married.” That’s not in his knowing at that point, unless you dump it on him. He may not see his dog again, but that’s not the same thing as the parents’ grief over all that they’re anticipating losing over a lifetime.

Harris: So, the truth that exists to be told to the child is not the same as the parents’ anticipated loss, or their ideas about what the child himself will be losing.

Howard: Right. Telling the kid, “It’s really sad you’re dying because you’re not going to get married” misses the point. You might as well say, “You’re also not going to serve in the Army. You’re not going to kill people. You’re not going to experience the death of other people that you love.” You see? That’s life. It doesn’t all have a Hollywood ending. There are lots of pluses and minuses. Ultimately, we all die, and the only question is, what have you done between the time you’re born and the time you die? Did you make the most of this unique opportunity?

Harris: I agree with all that. But cases of this kind seem to suggest certain caveats to scrupulous truth-telling. There still seems to be a tension between honesty and our responsibility to protect children and other people whom we might judge to be not entirely competent to deal with the truth as we see it. So, let’s say you take all the time required to figure out what the truth really is, and yet you are in the presence of someone, whether a child or an adult, who you think needs to be spared certain truths. Other examples of this have come to me from people who are caring for parents with dementia. Your mother wakes up every morning wondering where your father is, but your father has been dead for fifteen years. Every time you explain this, your mother has to relive the bereavement process all over again, only to wake up the next morning looking for her husband. Let’s assume that when you lie, saying something like “Oh, he’s away on a business trip,” your mother very quickly forgets about your father’s absence and her grief doesn’t get reactivated.

Howard: That’s an interesting one. I would be tempted to say something more like “Well, he’s where he usually is at this time of day.” Like, he is someplace, and it’s where he usually is. The fact that he’s buried in the ground somewhere doesn’t add anything to this person’s knowledge of what’s going on. As you point out, you would just be putting her through pain all over again. As you stated the case, why would you want to do that?

Harris: What you seem to be acknowledging here, however, is that it is okay to be somewhat evasive in situations of this kind. At the very least, it can take some skill to thread the needle and find a truth that is appropriate to the other person’s situation.

Howard: I’d call it “skillful truth-telling” as opposed to “evasion,” in the sense that if this person had looked at the whole conversation—let’s say they magically get better again and could say, “Oh, I had Alzheimer’s. How did you deal with me when I kept asking about Dad?” They would look at the transcript and say, “You know, that’s right. In my mind, he was someplace, and I just didn’t know where he was. What you said allowed me to get out of that loop.” That’s fine.

Harris: I’m just going to keep throwing difficult cases at you, Ron.

Howard: You go right ahead.

Harris: Let’s again invoke a deathbed scene, where the dying person asks, “Did you ever cheat on me in our marriage?” Let’s say it’s a wife asking her husband. The truthful answer is that he did cheat on her. However, the truth of their relationship—now—is that this is completely irrelevant. And yet it is also true that he took great pains to conceal this betrayal from her at one point, and he has kept quiet about it ever since. What good could come from telling the truth in that situation?

Howard: Well, this is really a two-part problem, and the first part is, why would this husband want to live a lie all his life?

Harris: I agree. But we have to put a frame around the relevant facts of the present, and if a person hasn’t been perfectly ethical up until yesterday, he has to figure out how to live with the legacy of his misbehavior. This thing is buried in the past. He hasn’t thought about it in forever, but the truth is that he did cheat on his wife, and now she’s asking about it. In his mind, he seems to have a choice between lying and having a perfectly loving last few days or weeks of his marriage, and breaking his wife’s heart for no good reason.

Howard: Well, this is one of those textbook situations that we sometimes get into in ethics class. The terrorists get aboard the plane and try to make you kill a little old lady, threatening that they’re going to shoot everybody else if you don’t. Life doesn’t really work like that. I know of very few marriages, for example, where the husband has cheated and the wife didn’t suspect it.

Harris: I can’t let you off that easily. I think there’s something realistic about a case like this. We can even grant that she did suspect it all those years, and she buried her suspicion. Now she’s on her deathbed, and she finally wants the truth, for whatever reason.

Howard: Then they’ve had a silent conspiracy to not talk about this thing their whole life. Now what? In other words, she bears the responsibility as much as he does. The question is, are they going to start living an open life now and be truthful to each other, or not? They could do it. He could say, “We’ve never talked about this. Is this something you really want to talk about today?” This may be the time, whatever their beliefs about what happens after death. Or he could say, “Look, we’ve got a very short time together, and whatever we’ve done in the past, if it doesn’t bring us joy now, let’s leave it behind.”

Harris: It’s interesting—there seems to be an odd intuition working in cases like this, which I only just noticed in myself: If we shorten the time horizon down to a few days, or a few weeks, or even a few months, it seems to put pressure on the rationale for living truthfully. Many people seem to feel that if we only have two weeks left together, it’s probably better to live a consoling lie, but if we have 20 years left, then we might want to put our house in order and live truthfully.

Howard: I look at it another way: No matter how much time I’ve got left, I want to live a life that I have no regrets about.

Harris: I agree. But I think that there might be a moral illusion creeping in here. When you dial the remainder of one’s life down to a very short span, people begin to wonder, what good could possibly come from telling the truth? In my view, one might as well apply that thinking to the whole of life.

Howard: Absolutely. This gets to the very foundation of what we’re talking about here, which is how you want to live your life and care for the people in it. My father used to talk about someone being a man of his word, and I guess maybe it’s sexist these days, but I never hear that anymore. Clint Korver, my doctoral student who has helped me teach my course and write our ethics book, was once introduced at a conference, quite correctly, as “the guy who always tells the truth.” I find it absolutely shocking that anyone would need to mention that. It’s like saying he doesn’t steal or murder people. Why not say, “and he breathes, too”? “He’s lived for many years, and he’s been breathing all this time.” Great. Glad to hear it.

Harris: It just indicates how commonplace lying is. It’s ubiquitous, and most people don’t even consider what life would be like without it.

Another difficult case comes to mind, also from a reader: You’re having sex with your wife or husband and fantasizing about someone else. Later, your spouse has the temerity to ask what you were thinking about when you were having sex. The honest answer is that you were thinking about someone else. But let’s say that you know your spouse will not do well with this information. He or she will view it as a real breach of trust, rather than just a natural consequence of having a human imagination.

Howard: Well, that’s another case in which, when you first suspect this, it’s probably time to have a conversation. Just what is okay? Is it “whatever turns you on”?—you know, “I could be the pirate and you could be the helpless maiden…” and so forth. Is that okay? Or is it “Oh, my god, you’re not seeing me as I really am.” People will obviously differ in this area, but couples just need to have an honest conversation about it. I think honesty really is all that matters. It just transforms the situation.

Why would you want to live a lie in your sex life? It just seems silly to live a life of pretense, and it’s okay to have fantasies. Why not say, “Look, if it turns you on to think that I’m Brad Pitt, it’s going to be more fun for me when you’re turned on, so go for it. Because that’s why I’m here in the first place, right? I love you, and I want to have the best life with you that we can have.”

Harris: I can feel our readers abandoning us in droves, but I agree with you. Let’s return to the case in which you are in the presence of someone who seems likely to act unethically. Can you say more about honesty in those situations?

Howard: Well, I’d make a distinction between the maxim-breakers—in other words, a person who is harming others or stealing—and those who are merely lying or otherwise speaking unethically. Lying is not a crime unless it’s part of a fraud. If someone asks for directions to Wal-Mart, and you know the way but you send them walking in the opposite direction—it’s not a nice thing to do, but it’s not a crime. Imagine if they came back with a policeman and said, “That’s the man who misdirected me.” You could say, “Yeah, I did. It just so happens that I like to watch people wandering in the wrong direction.” That’s not a crime. It’s not nice behavior. It might be reason for someone to boycott your business, or to exclude you from certain groups, but it’s not going to land you in jail.

I make a careful distinction between what I call “maxim violations”—interfering with peaceful, honest people—and everything else.

Harris: Yes, I see. It breaks ethics into two different categories—one of which gets promoted to the legal system to protect people from various harms.

Howard: In fact, there are also two categories in the domain of lying. The first is where people acknowledge the problem—people obviously get hurt by lies—and then the other cases where more or less everyone tends to lie and feels good about it, or sees no alternative to it. That’s why your book is so important—because people think it’s a good thing to tell so-called “white” lies. Saying “Oh, you look terrific in that dress,” even when you believe it is unattractive, is a “white” lie justified by not hurting the person’s feelings.

The example that came up in class yesterday was, do you want that mirror-mirror-on-the-wall-who’s-the-fairest-of-them-all device, or do you want a mirror that shows you what you really look like? Or imagine buying a car that came with a special option that gave you information that you might prefer to the truth: When you wanted to go fast, it would indicate that you were going even faster than you were. When you passed a gas station, it would tell you that you didn’t need any gas. Of course, nobody wants that. Well, then, why would you want it in your life in general?

Harris: However, there are some arguments, from both an evolutionary and a psychological perspective, that suggest that having one’s beliefs ever-so-slightly out of register with reality can be adaptive and psychologically helpful. I’m sure you’re familiar with the research that shows that if you bring a person into a room full of strangers and have him give a brief speech, a depressed person will tend to accurately judge what sort of impression he has made, while a normal person will tend to overestimate how positively others saw him. It’s hard to know which is cause and which is effect here—but it does seem like an optimism bias could be psychologically advantageous.

Howard: It might have allowed people to survive a lot better in the past.

Harris: Yes. In fact, self-deception could have paid evolutionary dividends in other ways. Robert Trivers argues, for instance, that people who can believe their own lies turn out to be the best liars of all—and an ability to deceive rivals has obvious advantages in the state of nature. Now, obviously there are many things that may have been adaptive for our ancestors—such as tribal warfare, rape, xenophobia, etc.—that we now deem unethical and would never want to defend. But I’m wondering if you see any possibility that a social system that maximizes truth-telling could be one in which the wellbeing of all participants fails to be maximized. Is it possible that some measure of deception is good for us?

Howard: This gets back to distinctions I make between prudential, ethical, and legal principles. Is the statement “Honesty is the best policy” a prudential statement? In other words, is it merely in your interest to be honest? That’s different from saying, “I am ethically committed to being honest,” because you could probably find individual circumstances where dishonesty gives you an advantage.

I think that growth is encouraged by accurate feedback. Telling children they are always accomplishing wonderful things regardless of their actual accomplishments is not going to serve them when they face the world. Having a positive mental attitude toward life is prudential, but being overconfident in your abilities is not.

A student yesterday said that he had recently bid for something, and he told the guy that he didn’t have enough money to pay the full price. But this was a lie. He really had the money, but he said, “I only have X,” and the seller said, “Okay. I’ll give it to you for X, if that’s all the money you have.” So my student was feeling pretty good about this negotiation because, from his point of view, he saved money by telling an untruth. But it’s also possible the seller could have said, “Sorry. I’ve got other offers at the price X+1,” in which case my student would have been exposed in his lie if he really wanted the item and said, “Okay, I’ll pay X+1 too.” This all gets to the question of whether you have repeated relationships. Do you view your life in terms of relationships or transactions?

If you’re bidding on eBay, truth isn’t an issue. This is a completely transactional situation. If I’m dealing with my mechanic on an ongoing basis, it’s not a transaction. It’s a relationship, and he will make judgments about me and about my reliability as a person. And I will make these judgments about him, and these judgments will have long-term effects for both of us. This alters the prisoner’s dilemma: If you have a relationship with a person, you’re going to have different beliefs about the prospect of him selling you out than you would if he were just some guy the experimenters grabbed and put in the situation with you.

I don’t think you can get from “is” to “ought” in the coarse sense of saying that ethical people make more money, are always happier, etc. That would be to prove that it is always prudential to be ethical. Now, I personally believe it generally is, but I can’t prove that.

Harris: I agree. But you seem to have a very strong intuition, which I share, that we should consider honesty to be a nearly ironclad principle, because it is to everyone’s advantage so much of the time, and it allows us to live the kinds of lives and maintain the kinds of relationships we want to have.

Howard: And I believe it also extends to truths about oneself. Self-deception isn’t of any value either. For instance, I was never going to be a professional singer. If I didn’t understand this fact about myself, people could have said, “Oh, you’re a great singer. You ought to quit your job and start recording.” But that’s just bullshit. You’ve got to be honest about who you are—about what you know and don’t know and about what you can and can’t do—and still be willing to try things and experiment. To me, it’s pretty simple.

Harris: And, needless to say, it makes sense to want to be in touch with reality. Given that your every move in life will be constrained by whatever the facts are, both out in the world and in the minds of others, being guided by anything less than these facts will leave you perpetually vulnerable to embarrassment and disappointment. When your model of yourself in the world is at odds with how you actually are in the world, you are going to keep bumping into things.

I think where people get confused, psychologically and ethically, is when they consider that part of reality that exists in other people’s minds. The question is, do you really want to know what other people think about you—about your talents and prospects—or do you want to be deceived about all that?

Many people imagine that they want to be protected from the knowledge of what is really going on in the heads of other people, because they think their own performance in the world will be best served by this ignorance. I think they’re mistaken, but it’s interesting to consider cases where they might be right.

Howard: It is—and that gets down to the question of what your view is towards life as a whole. I tend to go back to something like the Buddha’s eightfold path. I remember hearing a Buddhist speaker once give a talk, and at question time a woman said, “I was raised as a Christian, where the idea of charity is built in, and yet you haven’t mentioned charity at all. So I’m having trouble understanding your ethics.”

And he said to her, “Well, when you were doing all these charitable things”—which she said she regularly did at church, helping people all over the world, sending them baskets and stuff—“did you really care about these people you were doing these things for?” The woman was silent for a moment and then she said, “No. I hadn’t really thought about that.” And the teacher said, “Well, when you care, you’ll know what to do.”

That’s so different from saying, “You’ve got to be charitable.” When you actually care about the experience of other people, you tend to know what to do. The conversation you and I are having now is kind of like writing a manual for unenlightened people like ourselves, so we all won’t make too many mistakes along the way.

I sometimes use a metaphor of the guy who never knew he had to put oil in his new car, because no one ever told him. He never read the manual, and now after three years the engine is burned out. He takes the car into the shop and the mechanic says, “Hey, you have to put oil in these things. Now your engine is ruined.” And the man says, “Oh, if only I’d known!” You see, he had no intention of creating this problem that he now has to solve. Well, in speaking about ethics, you and I are trying to raise everyone’s sensitivities, so that we all can live in a preemptive way, as opposed to saying, “Oh my god, what was I thinking?” later on.

Harris: That’s what I felt when I first took your course at Stanford. It was as if I had been given part of the user’s manual to a good life, and by following the simple principle of always telling the truth, I could bypass most of the needless misery I read about in literature and witnessed in the lives of other people. I remember leaving your course feeling that I had discovered a bomb at the very center of my life and had defused it before it could do any damage. It was a tremendous relief.

I’ve begun to wonder, however, at what level the ethical problems we see in the world can be best addressed. The level we tend to speak about, as we have here, is that of a person’s personal ethical code and his individual approach to life, moment to moment. But I suspect that the biggest returns come at the level of changing social norms and institutions—that is, in creating systems that align people’s priorities so that it becomes much easier for ordinary people to behave more ethically than they do when they are surrounded by perverse incentives. For instance, a person usually has to be a hero to be a whistle-blower, given that he will likely lose his job for telling the truth. But in a culture of honesty, it becomes much easier to be truthful. I’m interested in those changes we can make that will cause all boats to rise with the same tide.

Howard: Right. And in my own life I know that I don’t want to do business with people that I’m not on the same ethical wavelength with, so to speak. No matter how attractive the deal looks, if I don’t trust these people—in the sense that you and I are talking about—I don’t want to do business with them, no matter how profitable it might be.

But the problem is that a lot of our life today is transactional. I just bought something from Amazon.com, and there was nobody there, so to speak. It was just credit cards and button clicks. If you go to the supermarket today,the laser system tells you what the price is and the checker bags it for you. In the old days it might be, “Oh you bought a lot of spaghetti. Do you have sauce for that?” There’s no feeling that the checker is a partner in this experience of buying something.

I have this example of what I call the hardware store hammer: A woman is in a hardware store and picks up a hammer. When she is checking out, the shop owner says, “What are you going to use this hammer for?” And she says, “My husband told me to buy a hammer. We’re putting up some pictures in the kitchen.” The owner might say, “Okay. But this is a professional carpenter’s hammer. For your purpose, that one over there would do just fine, and it’s a third the price.” That’s the difference between a relationship and a transaction. If you have a concern for other people doing well for themselves, then I think you want this level of honesty. But our society might be losing that.

We have a great technological advantage, but it’s not like when my father ran a grocery store. If the kids didn’t arrive with enough money, he knew who was who, and it was not a problem. They could just bring the money next time. You don’t see much of that today. Now, you’ve got your credit card, and the idea of extending that kind of trust and courtesy just doesn’t come up anymore. So certain kinds of relationships seem less possible.

Harris: Yes, a system-wide change can either facilitate our ethical connections to other people, or erode them. This brings me to a related question: Are there some things that are important to do—that is, ultimately ethical to do—but which require that the person doing them sacrifice his ethics? I brought this up briefly in my book where I talk about spying. The position I take in the book is that there are certain jobs that I know I would not want to do, and I suspect that they are intrinsically toxic for the person who has to do them, but I can’t say that I think these jobs are unnecessary. I’m thinking of things like espionage, or research on animals. I know that I don’t want to be the guy who saws the scalps off rats all day, but I’d be hard-pressed to say we shouldn’t be using rats in medical research. So, assuming you are going to grant that espionage is occasionally necessary, what do you think about the lifetime of lying entailed by working at the CIA?

Howard: You could also consider what it’s like to be an undercover police officer.

Harris: Yes, that might be an even simpler case. Assuming the laws he is working to enforce are good ones. I know you and I agree on how harmful the war on drugs has been. If an undercover cop were deceiving people to enforce drug laws, I think we would both question the ethics of that line of work.

Howard: Exactly. I’d want to first make sure the cop is enforcing good laws. If it’s a serial rapist found, that’s fine. I’m happy to have police who are out there finding those people and bringing them to justice. We all pay a huge price for living in a world with people who are maxim-breakers. I wish we could live in a world where no one had to use passwords, for instance. But we have passwords and burglar alarms and keys… If you go out in the country, people say, “You mean you don’t leave your key in the car? And you lock your house?”

That’s why I want a very strong system to deter maxim-breakers that is based on restitution. In other words, some of these things that you do are imposing costs on everyone else. I’ve never been burglarized, but I’m paying the price for people who commit burglary, through insurance and other costs. If you engage in that sort of behavior, you ought to pay the criminal overhead for it. But that’s a longer story.

Harris: I completely agree with that as well.

Howard: The trouble is that we can’t separate these things when we get into the kind of discussion we’re having now—What kind of crimes are there in society, and how do you find the people who are perpetrating them? What kind of judgment do they get, and what are the penalties for having done these things? etc. This is a book all in itself, but it’s extremely important.

Harris: No doubt. Well, Ron, this has been great, and I think that readers will find your thoughts on all these topics very useful. Thank you for taking the time to speak with me. And let me say again, in case I never fully expressed it, that the courses you taught at Stanford were probably the most important I ever took. It’s rare that one sees wisdom being directly imparted in an academic setting. But that is what you did, and have continued to do for decades. So I just want to say, “Thank you.”

Howard: You are very welcome. And it was great to have this conversation.

April 19, 2013

New Atheism should be able to criticise Islam without being accused of Islamophobia

April 8, 2013

On “Islamophobia” and Other Libels

(Photo by kevin dooley)

A few of the subjects I explore in my work have inspired an unusual amount of controversy. Some of this results from real differences of opinion or honest confusion, but much of it is due to the fact that certain of my detractors deliberately misrepresent my views. I have responded to the most consequential of these distortions here.

April 7, 2013

Response to Controversy

A few of the subjects I explore in my work have inspired an unusual amount of controversy. Some of this results from real differences of opinion or honest confusion, but much of it is due to the fact that certain of my detractors deliberately misrepresent my views. The purpose of this article is to address the most consequential of these distortions.

(Photo by kevin dooley)

Version 2.3 (April 7, 2013)

A few of the subjects I explore in my work have inspired an unusual amount of controversy. Some of this results from real differences of opinion or honest confusion, but much of it is due to the fact that certain of my detractors deliberately misrepresent my views. The purpose of this article is to address the most consequential of these distortions.

A general point about the mechanics of defamation: It is impossible to effectively defend oneself against unethical critics. If nothing else, the law of entropy is on their side, because it will always be easier to make a mess than to clean it up. It is, for instance, easier to call a person a “racist,” a “bigot,” a “misogynist,” etc. than it is for one’s target to prove that he isn’t any of these things. In fact, the very act of defending himself against such accusations quickly becomes debasing. Whether or not the original charges can be made to stick, the victim immediately seems thin-skinned and overly concerned about his reputation. And, rebutted or not, the original charges will be repeated in blogs and comment threads, and many readers will assume that where there’s smoke, there must be fire.

Such defamation is made all the easier if one writes and speaks on extremely controversial topics and with a philosopher’s penchant for describing the corner cases—the ticking time bomb, the perfect weapon, the magic wand, the mind-reading machine, etc.—in search of conceptual clarity. It literally becomes child’s play to find quotations that make the author look morally suspect, even depraved.

Whenever I respond to unscrupulous attacks on my work, I inevitably hear from hundreds of smart, supportive readers who say that I needn’t have bothered. In fact, many write to say that any response is counterproductive, because it only draws more attention to the original attack and sullies me by association. These readers think that I should be above caring about, or even noticing, treatment of this kind. Perhaps. I actually do take this line, sometimes for months or years, if for no other reason than that it allows me to get on with more interesting work. But there are now whole websites—Salon, The Guardian, Alternet, etc.—that seem to have made it a policy to maliciously distort my views. I have commented before on the general futility of responding to attacks of this kind. Nevertheless, the purpose of this article is to address the most important misunderstandings of my work. (Parts of these responses have been previously published.) I encourage readers to direct people to this page whenever these issues surface in blog posts and comment threads. And if you come across any charge that you think I really must answer, feel free to let me know through the contact form on this website.

My views on Islam (get link)

My criticism of faith-based religion focuses on what I consider to be bad ideas, held for bad reasons, leading to bad behavior. Because I am concerned about the logical and behavioral consequences of specific beliefs, I do not treat all religions the same. Not all religious doctrines are mistaken to the same degree, intellectually or ethically, and it would be dishonest and ultimately dangerous to pretend otherwise. People in every tradition can be seen making the same errors, of course—e.g. relying on faith instead of evidence in matters of great personal and public concern—but the doctrines and authorities in which they place their faith run the gamut from the quaint to the psychopathic. For instance, a dogmatic belief in the spiritual and ethical necessity of complete nonviolence lies at the very core of Jainism, whereas an equally dogmatic commitment to using violence to defend one’s faith, both from within and without, is similarly central to the doctrine of Islam. These beliefs, though held for identical reasons (faith) and in varying degrees by individual practitioners of these religions, could not be more different. And this difference has consequences in the real world. (Let that be the first barrier to entry into this conversation: If you will not concede this point, you will not understand anything I say about Islam. Unfortunately, many of my most voluble critics cannot clear this bar—and no amount of quotation from the Koran, the hadith, the ravings of modern Islamists, or from the plaints of their victims, makes a bit of difference.)

Facts of this kind demand that we make distinctions among faiths that many confused or dishonest people will interpret as a sign of bigotry. For instance, I have said on more than one occasion that Mormonism is objectively less credible than Christianity, because Mormons are committed to believing nearly all the implausible things that Christians believe plus many additional implausible things. It is mathematically true to say that whatever probability one assigns to Jesus’ returning to earth to judge the living and the dead, one must assign a lesser probability to his doing so from Jackson County, Missouri. The glare of history is likewise unkind to Mormonism, for we simply know much more about Joseph Smith than we do about the twelve Apostles, and we have very good reasons to believe that he was a gifted con man. It is not a sign of bigotry against Mormons as people to honestly discuss these things. And I believe that atheists, secularists, and humanists do the world no favors by insisting that all religions be criticized in precisely the same terms and to the same degree.