Sam Harris's Blog, page 25

August 25, 2012

The God of Independent Minds

August 14, 2012

Poll shows atheism on the rise in the U.S.

August 7, 2012

Wrestling the Troll

The Internet powerfully enables the spread of good ideas, but it works the same magic for bad ones—and it allows distortions of fact and opinion to become permanent features of our intellectual landscape. Consequently, the migration of our cultural discourse into cyberspace can injure a person’s reputation in ways that may be impossible to remedy.

Anyone familiar with my work knows that I have not shied away from controversy and that many of my views defy easy summary. However, I continue to learn the hard way that if an issue is controversial, and my position cannot be reduced to a simple sentence, my critics will do the work of simplification for me. Topics like torture, recreational drug use, and wealth inequality can provoke outrage and misunderstanding in many audiences. But discussing them online sets your reputation wandering like a child across a battlefield—perpetually. Anything can and will be said at your expense—or falsely attributed to you—today, tomorrow, and years hence. Needless to say, the urge to respond to this malevolence and obfuscation can become irresistible.

The problem, however, is that there is no effective way to respond. Here is a glimpse of what it is like for me to sit at my desk, attempting to write my next book, while persistent and misleading attacks on my work continue to surface on the Internet.

* * *

I receive a stream of emails demanding to know why I continue to ignore Theodore Sayeed’s demolition of me on the website Mondoweiss. The answer: I’ve never heard of Theodore Sayeed or Mondoweiss. A subsequent glance at his article reveals misrepresentations of my views and tendentious maneuvers that seem to have been made in very bad faith. Engaging with this sort of thing only gives it greater currency—or so I like to believe, given that I have no time to engage with it. Strangely, my commitment to safeguarding my time doesn’t stop me from spending half an hour writing personal emails to a handful of readers explaining why I think a response to Sayeed is beneath me.

* * *

Another flurry of emails arrives alerting me to a very personal and misleading attack on me (along with a few friends and colleagues) now lighting up Alternet—a website that has distorted my views in the past. Many readers want to know when they can expect my response to “The 5 Most Awful Atheists.” I read this poisonous and inane concoction written by a deeply unserious person who has made no effort to understand my arguments, and I decide that the best thing to do is to forget all about it.

Predictably, this article refers to the fact that I have discussed the ethics of torture in the past—and it does so in order to brand me as a moral lunatic. From reading this piece, and hundreds like it, one would never imagine that my position on torture is more or less identical to the one prescribed in that handbook of evil, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (Read the entry on torture there, especially the section entitled “The Beating,” and then tell me that being categorically “against torture” is a morally uncomplicated stance to adopt.)

However, I then hear that the article has been gleefully endorsed by that shepherd of Internet trolls PZ Myers, amplifying its effect. Soon thereafter it appears on Salon, under the slightly more restrained title “5 Atheists who ruin it for everyone else.” Will I now respond? The temptation is growing. But I have 5,991 unread emails in my inbox and a book to write.

* * *

I check my email again (this is always a mistake), and discover that one of my pen pals considers my failure to respond to Sayeed a telling sign of intellectual dishonesty. She goads me with the following:

So, the same response to Jackson Leer’s [sic] deconstruction of your work. What, precisely, was “too idiotic to merit a response?” It seemed like a very fair and factual attack on your work, although I must admit it’s been sometime [sic] since I read The End Of Faith.

The blow lands and jogs my memory. Jackson Lears: He was the historian who wrote a blistering review of my work in The Nation. Although I linked to his essay on my website, I did not answer it either—apart from saying that it “may be the most idiotic and unbalanced response to my work I have ever come across.” Perhaps I should have tackled Lears. The Nation, after all, is a “real” magazine—albeit one that gets less online traffic than either Alternet or Salon, and not much more than PZ Myers’s odious blog.

What my email correspondent could not know is that I contacted Lears in the hope of doing something more interesting and productive than writing a long and boring rejoinder to his long and boring review. After his piece appeared in the The Nation, I sent Lears the following email:

Jackson—

Over the past month, many people have written to me insisting that I comment on your recent review of my work. I have occasionally responded to negative reviews, op-eds, and other written attacks in the past, but your Nation piece was so long and unremitting that it is difficult to know where to begin. And, because I do not recognize myself in your review, I am struck less by your specific points and more by the distance between us. The juxtaposition of my work and your reaction to it reveals, more than anything, just how difficult communication can be.

So, rather than respond to your review with a separate volley of my own, I’m wondering if you would be willing to explore our differences in a written exchange. This might have some of the characteristics of a debate, but I’m more interested in it being a conversation, or mutual interview. We could publish it on my blog, and perhaps cross-post it on the Nation website.

Any interest?

Best,

Sam

Lears appeared to be quite surprised by this overture, in light of the harrowing he had given me, but, alas, he found that he did not have the time—or, I suspect, the desire—to attempt a meeting of the minds. Needless to say, I sympathized on both counts. Who has time for any of this?

* * *

Another attempt to write, and another email (I may be procrastinating):

Sam,

I’m a little late to the controversy, but I’m so glad your recent posts on

profiling are getting you the attention you deserve. Meaning, you’re finally

recognized as the bigot you are. It was all there in End of Faith, now it’s

apparent to everyone. Only die-hard fans will remain… Glad your 15 minutes are up.

You might think that it’s the triumphant ill will expressed here that gets under my skin—but you would be mistaken. What bothers me is the persistence of misunderstanding. I can’t shake the feeling that if I just wrote or spoke more clearly, this sort of thing wouldn’t happen.

What is the “controversy” that my correspondent finds so gratifying? A couple of months ago, I wrote an article on profiling at airport security checkpoints. Given that I suggested (twice) that white men like myself also fit the profile of a possible terrorist, I would have thought that charges of “racism” would be off the table. Not so. In fact, people like PZ Myers continue to malign me as an advocate of “racial profiling.” I have written to Myers personally about this and answered his charges publicly. His only response has been to attack me further and to endorse the false charges of others.

I do not think that I am being especially thin-skinned to worry about this. Accusations of racism and similar libels tend to stick online. If my daughter one day reads in my obituary that her father “was persistently dogged by charges of racism and bigotry,” unscrupulous people like PZ Myers will be to blame.

My correspondent is right about one thing, however: It was all there in my first book, The End of Faith. Since the moment I began criticizing religion in public, I have argued that Islam merits special concern—because it is currently the most militant and retrograde of the world’s major religions. This has always made certain people uncomfortable, because they find it difficult to distinguish a focus on Islam—specifically, on the real-world effects of its doctrines regarding martyrdom, jihad, apostasy, and the status of women—from bigotry against Muslims. But the difference is clear and crucial. My criticism of conservative Islam has nothing to do with race, ethnicity, or nationality. And, as I have often said, no one suffers the consequences of this pernicious ideology—the abridgments of political and intellectual freedom, the mistreatment of women, the fanaticism and sectarian murder—more than innocent Muslims.

In the hopes of achieving some clarity on the issue of profiling, I let the anti-profiling security expert Bruce Schneier write a guest post on my blog. I then engaged in a long and rather tedious debate with him. It seems that few minds were changed, including my own. I heard from many readers who took my side in the debate—including those who have worked in airport security, U.S. Customs, the FBI, Delta Force, fraud detection, and other areas where real-time threat assessments must be made. I also received unequivocal support from Saudis, Pakistanis, Indians, and others who are regularly profiled. However, I heard as well from many people who thought that Schneier mopped the floor with me. Some of these readers continue to wonder why I, being ostensibly committed to reason, haven’t publicly conceded defeat and changed my view.

There seems to be a consensus, even among my critics, that no one does airline security better than the Israelis (even Schneier admits this). But, as I pointed out, and Schneier agreed, the Israelis profile (in every sense of the term—racially, ethnically, behaviorally, by nationality and religion, etc.). In the end, Schneier’s argument came down to a claim about limited resources: He argued that we are too poor (and, perhaps, too stupid) to effectively copy the Israeli approach. That may be true. But pleading poverty and ineptitude is very different from proving that profiling doesn’t work, or that it is unethical, or that the link between the tenets of Islam and jihadist violence isn’t causal.

Schneier’s argument against profiling has almost nothing to do with the reasons that many people find profiling controversial. But none of my critics seemed to notice this. Nor did they notice when Schneier conceded that the most secure system would use a combination of profiling and randomness. He simply argued that profiling for the purpose of airline security is too expensive and impractical. But I am not being vilified because I advocated something expensive and impractical. I am being vilified because my critics believe that I support a policy that is shockingly unethical, well known to be ineffective, and the product of near-total confusion about the causes of terrorism.

Again, a feeling of hopelessness descends. I am confident that offering this brief postscript will prove counterproductive. Simply raising these issues—even to clarify misunderstandings—does little more than inspire trolls. If I cannot get my critics to acknowledge that I wasn’t advocating racial profiling—how can I discuss any serious and controversial issue online?

* * *

It is difficult to overlook the role that blog comments play in all this. Having a blog and building a large community of readers can destroy a person’s intellectual integrity—as appears to have happened in the case of PZ Myers. Many people who read his blog come away convinced that I am a racist who advocates the widespread use of torture and a nuclear first strike against the entire Muslim world. The most despicable claims about me appear in the comment thread, of course, but Myers is responsible for publishing them. And so I hold him responsible for circulating and amplifying some of the worst distortions of my views found on the Internet.

Incidentally, readers often ask why I haven’t enabled comments on my own blog, since they build a sense of community and generate traffic. Needless to say, I know that I have many smart and knowledgeable readers who have valuable insights to share on any topic I’m likely to touch. My reasons for not enabling comments are essentially the same as those given by Seth Godin on his blog. You can read his justification here. I also can’t spare the time to read hundreds of comments in an effort to determine whether they would contribute, however subtly, to the problem of noise and defamation that has now sucked me into its vortex. This is not to say that I don’t care what my readers think. As you can see, I do. And I do my best to read your emails. But generally speaking, I’m at the limits of my bandwidth and have to draw the line somewhere.

* * *

None of us know what our online lives will look like in five years. But we know that the Internet does not forget. And every day I confront the evidence of harm done to my reputation, and to the reputations of others, by people who seem accountable to no one apart from a growing army of trolls.

July 31, 2012

The Fall of Jonah Lehrer

The science journalist and author Jonah Lehrer seems to have driven his career off a cliff by, of all things, putting words into the mouth of Bob Dylan. He has resigned his post at The New Yorker and copies of his most recent bestseller have been recalled by his publisher.

I don’t know Lehrer personally, and I have only read one of his books in part and a few of his articles. However, I had seen enough to worry that he could get carried away by his talent for giving a journalistic polish to the research of others. There is no sin in being a science journalist—the world needs more of them—and Lehrer’s fall from grace is a genuine shame. But I know many scientists who felt that his commitment to the truth was tenuous. Recent revelations–about his manipulating and even inventing quotations, and telling elaborate lies to conceal his misbehavior–would appear to justify these fears.

Whenever I hear about a scandal of this kind, my first inclination is to find some exonerating details that make sense of it. There are surely many blameless paths to disgrace. I remember glimpsing one myself: I once spent several months dictating research notes into a tape recorder and sent the tapes out to be transcribed. This produced a text of over a thousand pages containing my disorganized opinions on everything high and low, along with many direct quotations from a wide range of sources. Upon reviewing it, I was horrified to discover that my long-suffering scribe had occasionally neglected to put quotation marks around the words of others. I do not have anything like a photographic memory—and given a sufficient interval I can find even my own writing unfamiliar. If I had waited a few more months to review this material, I could have easily plowed stray sentences or even whole paragraphs from other sources into my own work without realizing it.

Needless to say, I am now extremely careful in how I cite the work of other authors. But this experience has made me slow to judge anyone accused of plagiarism and other journalistic indiscretions. I suspect that many people found guilty of such crimes are guilty of nothing more than poor research practices.

Whatever the nature of Lehrer’s misdeeds, the outrageousness of the lies he subsequently told to a a fellow journalist—the diligent and Dylan-obsessed Michael Moynihan—is what has destroyed his reputation in a single stroke.

But even here, Lehrer is in good company. I consistently meet smart, well-intentioned, and otherwise ethical people who do not seem to realize how quickly and needlessly lying can destroy their relationships and reputations. And that is why I wrote a short ebook on the subject.

July 13, 2012

Have It Your Way

June 29, 2012

Reason for living: The good life without God

June 27, 2012

In Defense of “Spiritual”

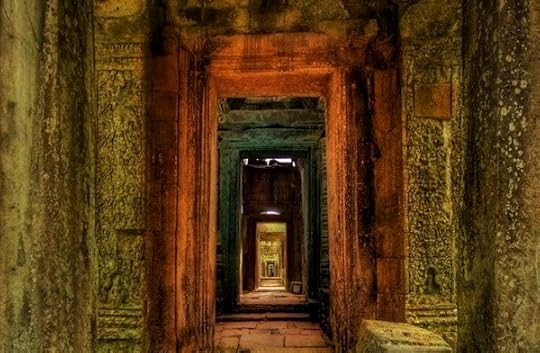

(Photo by Stuck in Customs)

In writing my next book, I will have to confront the animosity that many people feel for the term “spiritual.” Whenever I use the word—as in referring to meditation as a “spiritual practice”—I inevitably hear from fellow skeptics and atheists who think that I have committed a grievous error.

The word “spirit” comes from the Latin spiritus, which in turn descends from the Greek pneuma, meaning “breath.” Around the 13th century, the term became bound up with notions of immaterial souls, supernatural beings, ghosts, etc. It acquired other connotations as well—we speak of the spirit of a thing as its most essential principle, or of certain volatile substances and liquors as spirits. Nevertheless, many atheists now consider “spiritual” thoroughly poisoned by its association with medieval superstition.

I strive for precision in my use of language, but I do not share these semantic concerns. And I would point out that my late friend Christopher Hitchens—no enemy of the lexicographer—didn’t share them either. Hitch believed that “spiritual” was a term we could not do without, and he repeatedly plucked it from the mire of supernaturalism in which it has languished for nearly a thousand years.

It is true that Hitch didn’t think about spirituality in precisely the way I do. He spoke instead of the spiritual pleasures afforded by certain works of poetry, music, and art. The symmetry and beauty of the Parthenon embodied this happy extreme for him—without any requirement that we admit the existence of the goddess Athena, much less devote ourselves to her worship. Hitch also used the terms “numinous” and “transcendent” to mark occasions of great beauty or significance—and for him the Hubble Deep Field was an example of both. I’m sure he was aware that pedantic excursions into the OED would produce etymological embarrassments regarding these words as well.

We must reclaim good words and put them to good use—and this is what I intend to do with “spiritual.” I have no quarrel with Hitch’s general use of it to mean something like “beauty or significance that provokes awe,” but I believe that we can also use it in a narrower and, indeed, more transcendent sense.

Of course, “spiritual” and its cognates have some unfortunate associations unrelated to their etymology—and I will do my best to cut those ties as well. But there seems to be no other term (apart from the even more problematic “mystical” or the more restrictive “contemplative”) with which to discuss the deliberate efforts some people make to overcome their feeling of separateness—through meditation, psychedelics, or other means of inducing non-ordinary states of consciousness. And I find neologisms pretentious and annoying. Hence, I appear to have no choice: “Spiritual” it is.

June 23, 2012

Look Into My Eyes

I am currently under a book deadline, so long blog posts will probably be few and far between until the end of the year. The working title of the book is Waking Up: A Scientist Looks at Spirituality. This title could very well change, but this should give you some indication of what I’m up to. My goal is to write a “spiritual” book for smart, skeptical people—dealing with issues like the illusion of the self, the efficacy of practices like meditation, the cultivation of positive mental states, etc.

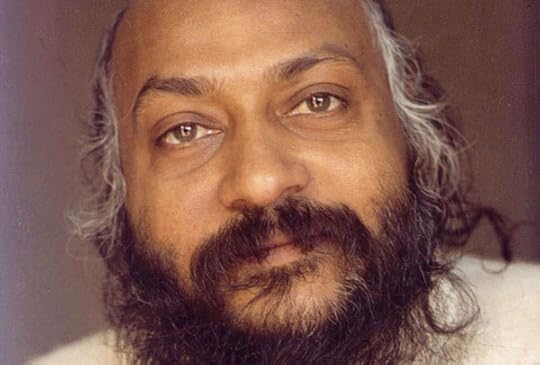

Writing this book has forced me to revisit the work of gurus and spiritual teachers at every point on the spectrum of wisdom and crackpottery—which has been a lot of fun.

One behavior that you can readily notice in many gurus, as well as in their students, is an unusual commitment to maintaining eye contact. In the best case, this behavior emerges from a genuine comfort in the presence of other people and deep interest in their well-being. Given this frame of mind, there may not be a reason to look elsewhere. But maintaining eye contact can also become a way of “acting spiritual”—and an intrusive affectation. Needless to say, there are people who maintain rigid eye lock, not from an attitude of openness and interest—or from a desire to appear open and interested—but as an aggressive and narcissistic show of dominance. (Psychopaths tend to make exceptionally good eye contact.) Whatever the motive behind it, there can be tremendous power in an unwavering gaze.

Most of you know what I’m talking about, but if you want to witness a glorious example of the grandiosity that a person’s eyes can convey, watch a few minutes of the following interview with Osho (Bhagwan Shree Rashneesh). I never met Osho, but I have met many people like him. He was by no means the worst that the New Age had to offer. He undoubtedly harmed many people in the end—and, perhaps, in the beginning and middle as well—but he wasn’t merely a lunatic or a con artist as many other gurus have been. Osho always seemed like a genuinely insightful man who had much to teach, but who grew increasingly intoxicated by the power of his role, and then finally lost his mind in it. When you spend your days sniffing nitrous oxide, demanding fellatio at 45-minute intervals, making sacred gifts of your fingernail clippings, and shopping for your 94th Rolls Royce… you should probably know that you’ve wandered a step or two off the path.

In any case, I find the way Osho plays the game of eye contact in this interview simply hilarious. This is what the Internet is for… Enjoy!

June 14, 2012

3 reasons young Americans are giving up on God

Islamophobia and Its Discontents

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9008 followers