Sam Harris's Blog, page 28

February 16, 2012

Life Without God

(Photo by H.koppdelaney)

Tim Prowse was a United Methodist pastor for almost 20 years, serving churches in Missouri and Indiana. Tim earned a B.A. from East Texas Baptist University, a Master of Divinity (M.Div) from Saint Paul School of Theology in Kansas City, Missouri, and a Doctor of Ministry (D.Min) from Chicago Theological Seminary. Acknowledging his unbelief, Tim left his faith and career in 2011. He currently lives in Indiana. He was kind enough to discuss his experience of leaving the ministry with me by email.

***

Can you describe the process by which you lost your belief in the teachings of your Church?

An interesting thing happened while I was studying at East Texas Baptist University: I was told not to read Rudolf Bultmann. I asked myself: Why? What were they protecting me from? I picked up Bultmann's work, and that decision is the catalyst that ultimately paved the road to today. Throughout my educational journey, which culminated in an Ordination from the United Methodist Church where I've served for seventeen years, I've continued to ask the question "Why?"

Ironically, it was seminary that inaugurated my leap of unfaith. It was so much easier to believe when living in an uncritical, unquestioning, naïve state. Seminary training with its demands for rigorous and intentional study and reflection coupled with its values of reason and critical inquiry began to undermine my naïveté. I discovered theologians, philosophers and authors I never knew existed. I found their questions stimulating but their answers often unsatisfying. For example, the Bible is rife with vileness evidenced by stories of sexual exploitation, mass murder and arbitrary mayhem. How do we harmonize this fact with the conception of an all-loving, all-knowing God? While many have undertaken to answer this question even in erudite fashion, I found their answers lacking. Once I concluded that the Bible was a thoroughly human product and the God it purports does not exist, other church teachings, such as communion and baptism, unraveled rather quickly. To quote Nietzsche, I was seeing through a different "perspective" – a perspective based on critical thinking, reason and deduction. By honing these skills over time, reason and critical thinking became my primary tools and faith quickly diminished. Ultimately, these tools led to the undoing of my faith rather than the strengthening of it.

It sounds like you lost your faith in the process of becoming a minister—or did you go back and forth for some years? How long did you serve as a minister, and how much of this time was spent riven by doubt?

I didn't lose faith entirely during the ministerial process, although a simmering struggle between faith and doubt was clearly evident. This simmering would boil occasionally throughout my seventeen-year career, but any vacillations I experienced were easily suppressed, and faith would triumph, albeit, for non-religious reasons. Besides the money, time, and energy I had invested during the process, familial responsibilities deterred any decisions to alter course. These faithful triumphs were ephemeral and I found myself living in constant intellectual and emotional turmoil. By not repudiating my career, I could not escape the feeling I was living a lie. I continued to juggle this stressful dichotomy to the point of being totally miserable. Only recently have I succumbed to the doubt that has always undergirded my faith journey.

After I read your book, The End of Faith, I could no longer suppress my unbelief. Since I'd never felt comfortable in clergy garb and refused to accept a first-century worldview, your book helped me see that religion could no longer be an instrument of meaning in my life. I'm sad to say, Sam, this conclusion did not result in an immediate career change. I didn't break from the church immediately, but rather feigned belief for two more years.

If you could go back in time and reason with your former self, what could you say that might have broken the spell sooner?

I would tell myself to ask questions, to read the text, to wonder, to explore the nuances, to take seriously my intuition and abilities to debate. I'd tell myself to listen to what is actually being said with critical and reasoning ears. I'd tell myself to substitute "Invisible Friend" for "God" every time I encountered the word and notice how ridiculous the rhetoric sounds from grown-ups. I would challenge myself to be more skeptical, to study science. I'd tell myself to find joy in life – it's the only one you are going to get – don't waste a second.

Believers often allege that there is a deep connection between faith and morality. For instance, when I debated Rick Warren, he said that if he did not believe in God, he wouldn't have any reason to behave ethically. You've lived on both sides of the faith continuum. I'm wondering if you felt any associated change in your morality, for better or worse.

I'd be interested to know what behaviors or impulses God is deterring Rick Warren from acting upon. I doubt very seriously if "God's goodness" evaporated tomorrow, Warren would begin robbing banks, raping children, or murdering his neighbors! These types of statements, while common, are fallacious in my opinion. When Rick Warren uses God as his reason for being good, he is not using God in a general sense. He isn't referring to Thor, Neptune, or Isis, either.

One can find a few biblical passages that do promote "goodness" to use Rick Warren's term, but only by cherry picking them and avoiding the numerous passages that are appalling, offensive and destructive.

Since God is nothing more than our creation and projection, any talk of God is our reflection looking back at us. Hence, our morality begins with us anyway. My morality hasn't changed for the worse since I left the faith. If anything, it is much more honest because I am forced to consider what is really going on in ethical decisions. Family, culture, beliefs and values, genetic tendencies, all play a role in shaping morality, but I'm not arguing an extreme relativism. While I do give credence to certain cultural influences on determining right and wrong, I believe that some issues are universal. Which is why, unless Rick Warren is truly demented, he wouldn't begin doing heinous acts if his faith evaporated tomorrow, and if he did, it would be more the result of mental illness than lack of faith.

Did you ever discuss your doubts with your fellow clergy or parishioners? Did you encounter other ministers who shared your predicament (some can be found at http://clergyproject.org/)? And what happened when you finally expressed your unbelief to others?

As an active minister, I did not discuss my atheism with colleagues or parishioners. Facing lost wages, housing and benefits, I chose to remain silent. However, I did confide in my wife who provided a level of trust, understanding, and support that proved invaluable. Unfortunately, some ministers do not enjoy mature confidants. Some have lost marriages and partners, friends and family, leaving them with feelings of isolation and abandonment. Hence, many continue living in estrangement, uncertain where to turn or who to trust, waiting for their lives to be completely upended when the truth finally is discovered.

This is why the Clergy Project is so important. It provides an invaluable resource of support for current and former clergy who are atheists. It is a safe and anonymous place to discuss the issues atheist clergy encounter while providing encouragement and support that is genuine and heartfelt. It greatly eases the desperation and uncertainty of where to turn or who to trust! I've been a member of the Clergy Project since July 2011, and it prepared me well for the responses to expect from friends and family during my post-clergy conversations. So far, I have not been surprised by the responses I've received nor have I lost any significant relationships due to my professed atheism, but time will tell.

It is nice to hear that your exit from the ministry has been comparatively smooth. What will you do next?

Repudiating my ordination and leaving faith behind was much smoother than I had anticipated. Ironically, something I had worked years to accomplish ended in a matter of minutes. When I slid my ordination certificates across a Bob Evan's tabletop to my District Superintendent, I was greatly relieved. The lie was over. I was free. This freedom does not come without consternation, however.

Fortunately, a dear friend helped my family by offering their second home to rent at a very reasonable price. Another dear friend has procured a sales job for me in her company. While housing and employment have been provided in the short term, long term my future is much more uncertain. Ideally, I'd love to write and lecture on my experiences; especially concerning the negative impacts faith and church have on individuals and societies. I'd love to write a novel.

I do not have visions of grandeur, however. If the rest of my life is spent just being a regular "Joe" that will be fine by me. I have a wonderful family and a few good friends. My heart and mind are at ease. I'm healthier now than I've been in years and tomorrow looks bright. For the first time in my life, I'm living. Truly living, Sam.

February 6, 2012

The Pleasures of Drowning

(Photo by Peter Gordon)

After writing an article on the principles of self-defense, I was inundated with emails and Internet comments—many of which came from experts in the field. The response was very supportive, and I haven't found anything of substance to amend in my original essay. However, I did take one criticism to heart: I don't know enough about Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ).

I am now doing my best to rectify that problem. What follows is the first installment of what (I hope) will be an ongoing journal of my progress in BJJ. I suspect that many readers of this blog have no interest in the martial arts and will consider this an unfortunate departure from my main areas of competence. I am convinced, however, that training in BJJ offers a powerful lens through which to examine some primary human concerns—truth v. delusion, self knowledge, ethics, and overcoming fear. I hope some of you bear with me.

* * *

Martial artists are often slow to appreciate how their beliefs about human violence can be distorted by their adherence to tradition, as well as by a natural desire to avoid injury during the course of training. It is, in fact, possible to master an ancient fighting system, and to attract students who will spend years trying to emulate your skills, without ever discovering that you have no ability to defend yourself in the real world. Delusions of martial prowess have much in common with religious faith. A crucial difference, however, is that while people of faith can always rationalize apparent contradictions between their beliefs and the data of their senses, an inability to fight is very easy to detect and, once revealed, very difficult to explain away.

There may be no case more perplexing or egregious than that of Yanagi Ryuken, a purported master of aikido. Master Ryuken apparently believed himself capable of defeating multiple attackers without deigning to touch them. Rather, he could rely upon the magic power of chi. Video of him demonstrating his devastating abilities shows that his students were grotesquely complicit in what must have been a long and colorful process of self-deception. Did these young athletes actually think that they were being hurled to the ground against their will? It is hard to know. What seems certain, however, is that Master Ryuken came to believe that he was invincible; otherwise he wouldn't have invited a martial artist from another school to come test his powers.

Here is the master in action:

And here is his belated encounter with physical reality:

Of course, it is sad to see a confused old man repeatedly punched in the face—but if you are a martial artist, or have even a passing concern with safeguarding basic human sanity, you will take some satisfaction in seeing a collective delusion so emphatically dispelled. (Just think of what must have been going through the minds of Master Ryuken's students as they witnessed this performance.)

Unfortunately, a similar form of self-deception can be found in most martial artists, because almost all training occurs with some degree of partner compliance: Students tend to trade stereotyped attacks in a predictable sequence, stopping to reset before repeating the drill. This staccato pattern of practice, while inevitable when learning a technique for the first time, can become a mere pantomime of combat that does little to prepare a person for real encounters with violence.

Another problem is that many combative techniques are too dangerous to perform realistically (e.g., gouging the eyes, striking the groin). As result, students are merely left to imagine that these weapons decisively end a fight whenever deployed in earnest. Reports from the real world suggest otherwise.

These concerns make BJJ and other grappling arts unique in two ways: BJJ can be safely practiced under conditions of 100 percent resistance and, therefore, any doubts or illusions about its effectiveness can be removed. Striking-based arts can also be performed under full resistance, of course, but not safely—because getting repeatedly hit in the head is bad for your health. And, whatever the intensity of training, it is difficult to remove uncertainty from the striker's art: Not even a professional boxer can be sure what will happen if he hits an assailant squarely on the jaw with a closed fist. The other man might fall to the ground unconscious, or he might not—and without gloves, the boxer might break his hand on the first punch. By contrast, even a novice at BJJ knows beyond any doubt what will happen if he correctly applies a triangle choke. It is a remarkable property of grappling that the distance between theory and reality can be fully bridged.

I can now attest that the experience of grappling with an expert is akin to falling into deep water without knowing how to swim. You will make a furious effort to stay afloat—and you will fail. Once you learn how to swim, however, it becomes difficult to see what the problem is—why can't a drowning man just relax and tread water? The same inscrutable difference between lethal ignorance and lifesaving knowledge can be found on the mat: To train in BJJ is to continually drown—or, rather, to be drowned, in sudden and ingenious ways—and to be taught, again and again, how to swim.

Whether you are an expert in a striking-based art—boxing, karate, tae kwon do, etc.—or just naturally tough, a return to childlike humility awaits you: Simply step onto the mat with a BJJ black belt. There are few experiences as startling as being effortlessly controlled by someone your size or smaller and, despite your full resistance, placed in a choke hold, an arm lock, or some other "submission." A few minutes of this and, whatever your previous training, your incompetence will become so glaring and intolerable that you will want to learn whatever this person has to teach. Empowerment begins only moments later, when you are shown how to escape the various traps that were set for you—and to set them yourself. Each increment of knowledge imparted in this way is so satisfying—and one's ignorance at every stage so consequential—that the process of learning BJJ can become remarkably addictive. I have never experienced anything quite like it. []

Most students of the martial arts have been aware of BJJ for years—since its emergence in the Ultimate Fighting Championship in 1993. The UFC was the first series of "mixed martial arts" (MMA) tournaments to get serious attention. The great novelty of these events is that they allow any style of fighting to be pitted against any other. Combatants from all disciplines—karate, boxing, Greco-Roman wrestling, muay Thai, kung fu, judo, tai kwon do, sambo, kickboxing, sumo, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, etc.—are simply placed in a ring (or, at the UFC, in an octagonal cage) in pairs. In the first years of the UFC, there were no weight divisions, rounds, or time limits and very few rules. In fact, there were no judges, because every fight ended by knockout, submission, referee stoppage, or a fighter's corner throwing in the towel.

Many people found the resulting spectacle horrifying—a modern version of the Roman games. But to the martial arts community the first UFC events were a science experiment that had been centuries in the making: Finally, there would be an answer to the one question of perennial interest to fighters everywhere: "What is the best method of fighting?" After a few hours, the answer seemed clear—and it wasn't boxing, wrestling, karate, or kung fu. Whatever a man's size, strength, skill, and prior training, a relatively diminutive practitioner of BJJ, Royce Gracie, could completely dominate him.

This revelation has acquired a few caveats in recent years, but two decades of pressure testing has confirmed its central truth. In the absence of rules, fighters of all styles tend to defensively grab hold of each other and grapple vertically. The significance of this "clinch" is disguised in sports like boxing and kickboxing because the referee repeatedly separates the two combatants. In the UFC, or in a real fight, the clinch tends to persist, often with the result that the bigger, stronger person, or the more experienced wrestler, takes his opponent to the ground. Once a fight goes to the ground, there is no substitute for knowing BJJ.

Today, more or less everyone training in MMA has absorbed this lesson, so the advantage of having a BJJ pedigree has been nullified. Martial artists from every discipline have added BJJ to their arsenals, and while the difference between being good at BJJ and being great can still be decisive, the fact that all competitors have good grappling skills has changed the character of the sport. Everyone now understands that the laws of physics dictate a right answer to the question, "What is the best method of fighting?", and all MMA fighters now do their best to embody it:

When you are standing at arm's length from your opponent, you want to be able to punch like a Western-style boxer and kick like a Thai boxer.

Moving closer, you want to remain a Thai boxer in your ability to strike with your knees and elbows.

Once your opponent grabs hold of you, or you him (the clinch), you want to have the skills of a Greco-Roman/freestyle wrestler—controlling his posture and throwing him to the ground at will. In the presence of sufficient clothing (jackets, coats, or traditional martial arts uniforms), this vertical grappling can take the form of judo. The general picture at this range is of two people being too close to strike one another effectively: You want to be the one who can move the fight to the ground on his own terms—by executing takedowns or throws—and who can resist being taken there.

And if the fight goes to the ground, the surest path to the safety of home remains Brazilian jiu-jitsu. The original revelation of the UFC still stands—with the coda that since everyone has now learned the same skills, an ability to strike on the ground has grown more important in MMA. Whether one practices BJJ by name doesn't necessarily matter, because other arts teach similar techniques—submission wrestling, sambo, etc. But no other discipline has mapped the frontiers of ground fighting the way BJJ has.

From a self-defense perspective, practicing BJJ exclusively can introduce one dangerous habit: Because BJJ is geared toward fighting on the ground, and is so decisive there, you can easily acquire a bias toward going to the ground on principle. When rolling on the mat, perfecting arm locks and chokes, it is easy to forget that in a real fight, your opponent is very likely to be punching you, or armed with a weapon, or in the company of friends who might be eager to kick you in the head (facts that are given cursory treatment in most BJJ training). To spend years perfecting the art of ground fighting is to risk forgetting that if a fight starts, the last place you want to be is on the ground.[]

To study BJJ for self-defense, therefore, is to prepare for the worst-case scenario—but the worst case remains a high probability in any sudden encounter with violence. If you are ever attacked by a bigger, stronger person, there is a very good chance you will find yourself on the ground, wrestling in some form. The difference between knowing what to do in this situation and merely relying on your primate intuitions is as impressive a gap between knowledge and ignorance as I have ever come across.

* * *

My thoughts on BJJ and self-defense have been greatly informed by discussions with Chris Haueter, Alex Stuart, and Matt Thornton.

Chris Haueter writes: As much as I loved wrestling, boxing, and muay Thai, there was something that struck me at such a primal level with my first experiences with BJJ that I became instantly hooked. I've come to believe that BJJ is the near perfect balance of sport/art/street. The fore mentioned three reality-based martial sports are powerfully athletic and explosive, and very much rely on natural talent and physical fitness; the fantasy martial arts (e.g. karate, tae kwon do, kung fu, aikido) can be just as beautiful, often more entertaining (at least as a spectator) but lack effective application in a real fight. BJJ is unique in that it is the art of controlling and submitting your opponent utilizing the minimal amount of strength, and the maximum amount of leverage, coupled with strategic guile. Like the reality-based martial sports, there is no room for untested theory, but unlike these sports BJJ can be practiced and improved upon without the bruises of strikes, body slamming takedowns, or a reliance on youthful athleticism. It is truly the intelligent art.↩

Matt Thornton writes: I agree we need all three ranges—stand up, clinch and ground—for self-defense; and, in general, we want to avoid going to the ground in a fight. However, the best way to ensure that you will end up on the ground is to never train there in the first place. It's the non-grapplers who are easiest to take down, and being in a "fight" means it isn't necessarily up to you where you end up. So, it's a bit of irony that wanting to stay off the ground in a self-defense situation should dictate a serious commitment to grappling.↩

February 5, 2012

Atheism in America

By Julian Baggini

Godlessness is the last big taboo in the US, where non-believers face discrimination and isolation

Go to article

It's good to be alive

February 2, 2012

The Fireplace Delusion

It seems to me that many nonbelievers have forgotten—or never knew—what it is like to suffer an unhappy collision with scientific rationality. We are open to good evidence and sound argument as a matter of principle, and are generally willing to follow wherever they may lead. Certain of us have made careers out of bemoaning the failure of religious people to adopt this same attitude.

However, I recently stumbled upon an example of secular intransigence that may give readers a sense of how religious people feel when their beliefs are criticized. It's not a perfect analogy, as you will see, but the rigorous research I've conducted at dinner parties suggests that it is worth thinking about. We can call the phenomenon "the fireplace delusion."

On a cold night, most people consider a well-tended fire to be one of the more wholesome pleasures that humanity has produced. A fire, burning safely within the confines of a fireplace or a woodstove, is a visible and tangible source of comfort to us. We love everything about it: the warmth, the beauty of its flames, and—unless one is allergic to smoke—the smell that it imparts to the surrounding air.

I am sorry to say that if you feel this way about a wood fire, you are not only wrong but dangerously misguided. I mean to seriously convince you of this—so you can consider it in part a public service announcement—but please keep in mind that I am drawing an analogy. I want you to be sensitive to how you feel, and to notice the resistance you begin to muster as you consider what I have to say.

Because wood is among the most natural substances on earth, and its use as a fuel is universal, most people imagine that burning wood must be a perfectly benign thing to do. Breathing winter air scented by wood smoke seems utterly unlike puffing on a cigarette or inhaling the exhaust from a passing truck. But this is an illusion.

Here is what we know from a scientific point of view: There is no amount of wood smoke that is good to breathe. It is at least as bad for you as cigarette smoke, and probably much worse. (One study found it to be 30 times more potent a carcinogen.) The smoke from an ordinary wood fire contains hundreds of compounds known to be carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, and irritating to the respiratory system. Most of the particles generated by burning wood are smaller than one micron—a size believed to be most damaging to our lungs. In fact, these particles are so fine that they can evade our mucociliary defenses and travel directly into the bloodstream, posing a risk to the heart. Particles this size also resist gravitational settling, remaining airborne for weeks at a time.

Once they have exited your chimney, the toxic gases (e.g. benzene) and particles that make up smoke freely pass back into your home and into the homes of others. (Research shows that nearly 70 percent of chimney smoke reenters nearby buildings.) Children who live in homes with active fireplaces or woodstoves, or in areas where wood burning is common, suffer a higher incidence of asthma, cough, bronchitis, nocturnal awakening, and compromised lung function. Among adults, wood burning is associated with more-frequent emergency room visits and hospital admissions for respiratory illness, along with increased mortality from heart attacks. The inhalation of wood smoke, even at relatively low levels, alters pulmonary immune function, leading to a greater susceptibility to colds, flus, and other respiratory infections. All these effects are borne disproportionately by children and the elderly.

The unhappy truth about burning wood has been scientifically established to a moral certainty: That nice, cozy fire in your fireplace is bad for you. It is bad for your children. It is bad for your neighbors and their children. Burning wood is also completely unnecessary, because in the developed world we invariably have better and cleaner alternatives for heating our homes. If you are burning wood in the United States, Europe, Australia, or any other developed nation, you are most likely doing so recreationally—and the persistence of this habit is a major source of air pollution in cities throughout the world. In fact, wood smoke often contributes more harmful particulates to urban air than any other source.

In the developing world, the burning of solid fuel in the home is a genuine scourge, second only to poor sanitation as an environmental health risk. In 2000, the World Health Organization estimated that it caused nearly 2 million premature deaths each year—considerably more than were caused by traffic accidents.

I suspect that many of you have already begun to marshal counterarguments of a sort that will be familiar to anyone who has debated the validity and usefulness of religion. Here is one: Human beings have warmed themselves around fires for tens of thousands of years, and this practice was instrumental in our survival as a species. Without fire there would be no material culture. Nothing is more natural to us than burning wood to stay warm.

True enough. But many other things are just as natural—such as dying at the ripe old age of thirty. Dying in childbirth is eminently natural, as is premature death from scores of diseases that are now preventable. Getting eaten by a lion or a bear is also your birthright—or would be, but for the protective artifice of civilization—and becoming a meal for a larger carnivore would connect you to the deep history of our species as surely as the pleasures of the hearth ever could. For nearly two centuries the divide between what is natural—and all the needless misery that entails—and what is good has been growing. Breathing the fumes issuing from your neighbor's chimney, or from your own, now falls on the wrong side of that divide.

The case against burning wood is every bit as clear as the case against smoking cigarettes. Indeed, it is even clearer, because when you light a fire, you needlessly poison the air that everyone around you for miles must breathe. Even if you reject every intrusion of the "nanny state," you should agree that the recreational burning of wood is unethical and should be illegal, especially in urban areas. By lighting a fire, you are creating pollution that you cannot dispose. It might be the clearest day of the year, but burn a sufficient quantity of wood and the air in the vicinity of your home will resemble a bad day in Beijing. Your neighbors should not have to pay the cost of this archaic behavior of yours. And there is no way they can transfer this cost to you in a way that would preserve their interests. Therefore, even libertarians should be willing to pass a law prohibiting the recreational burning of wood in favor of cleaner alternatives (like gas).

I have discovered that when I make this case, even to highly intelligent and health-conscious men and women, a psychological truth quickly becomes as visible as a pair of clenched fists: They do not want to believe any of it. Most people I meet want to live in a world in which wood smoke is harmless. Indeed, they seem committed to living in such a world, regardless of the facts. To try to convince them that burning wood is harmful—and has always been so—is somehow offensive. The ritual of burning wood is simply too comforting and too familiar to be reconsidered, its consolation so ancient and ubiquitous that it has to be benign. The alternative—burning gas over fake logs—seems a sacrilege.

And yet, the reality of our situation is scientifically unambiguous: If you care about your family's health and that of your neighbors, the sight of a glowing hearth should be about as comforting as the sight of a diesel engine idling in your living room. It is time to break the spell and burn gas—or burn nothing at all.

Of course, if you are anything like my friends, you will refuse to believe this. And that should give you some sense of what we are up against whenever we confront religion.

—

Recommended Reading:

Naeher et al. (2007). Woodsmoke Health Effects: A Review. Inhalation Toxicology, 19, 67-106.

January 29, 2012

The Smart List 2012: 50 people who will change the world

Welcome to the first Wired Smart List. We set out to discover the people who are going to make an impact on our future… So we approached some of the world's brightest minds—from Melinda Gates to Ai Weiwei—to nominate one fresh, exciting thinker who is influencing them, someone whose ideas or experience they feel are transformative.

January 15, 2012

Your God is My God

Governor Mitt Romney has yet to persuade the religious conservatives in his party that he is fit to be President of the United States. However, he could probably appease the Republican base and secure his party's nomination if he made the following remarks prior to the South Carolina Primary:

My fellow Republicans,

I would like to address your lingering concerns about my candidacy. Some of you have expressed doubts about my commitment to a variety of social causes—and some have even questioned my religious faith. Tonight, I will speak from the heart about the values that unite us.

First, on the subject of gay rights, let me make my position perfectly clear: I am as sickened by homosexuality as any man or woman in this country. It is true that I wrote a letter in 1994 where I said that "we must make equality for gays and lesbians a mainstream concern," and for this I have been mocked and pilloried, especially by Evangelicals. But ask yourselves, what did I mean by "equality"? I meant that all men and women must be given an equal chance to live a righteous life.

Yes, I once reached out to the Log Cabin Republicans—the gays in our party. Many people don't know that there are gay Republicans, but it is true. Anyway, in a letter to this strange group, I pledged to do more for gay rights than Senator Edward Kennedy ever would.

Well, Senator Kennedy is now deceased—so I don't have to do much to best him and keep my promise. But, more to the point, ask yourselves, what did I mean by "rights"? I meant that every man and woman has a right to discover the love of Jesus Christ and win life eternal. What else could I have meant? Seriously. What could be more important than eternal life? Jesus thought we all had a right to it. And I agree with him. And I think we should amend our Constitution to safeguard this right for everyone by protecting the sanctity of marriage.

I don't have to tell you what is at stake. If gays are allowed to marry, it will debase the institution for the rest of us and perhaps loosen its bonds. Liberals scoff at this. They wonder how my feelings for my wife Ann could be diminished by the knowledge that a gay couple somewhere just got married. What an odd question.

On abortion—some say I have changed my views. It is true that I once described myself as "pro-choice." But again, ask yourselves, what did I mean? I meant that every woman should be free to make the right choice. What is the right choice? To have as many children as God bestows. I once visited the great nation of Nigeria and a met woman who was blessed to have had 24 children—fully two-thirds of which survived beyond the age of five. The power of God is beyond our understanding. And this woman's faith was a sight to behold.

Finally, I would like to address the scandalous assertion, once leveled by the Texas Pastor, Robert Jeffress, that my church—the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is "a cult." In fairness, he almost got that right—the LDS Church is a culture. A culture of faith and goodness and reverence for God Almighty. Scientology is a cult—this so-called religion was just made up out of whole cloth by the science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard. But the teachings of my Church derive directly from the prophetic experience of its founder, Joseph Smith Jr., who by the aid of sacred seer stones, the Urim and Thummim, was able to decipher the final revelations of God which were written in reformed Egyptian upon a set golden plates revealed to him by the angel Moroni. Many of you are probably unfamiliar with this history—and some of you may even doubt its truth.

I am now speaking to the base of our party, to the 60 percent who believe that God created this fine universe, and humanity in its present form, at some point in the last 10,000 years. Let me make one thing absolutely clear to you: I believe what you believe. Your God is my God. I believe that Jesus Christ was the Messiah and the Son of God, crucified for our sins, and resurrected for our salvation. And I believe that He will return to earth to judge the living and the dead.

But my Church offers a further revelation: We believe that when Jesus Christ returns to earth, He will return, not to Jerusalem, or to Baghdad, but to this great nation—and His first stop will be Jackson County, Missouri. The LDS Church teaches that the Garden of Eden itself was in Missouri! Friends, it is a marvelous vision. Some Christians profess not to like this teaching. But I ask you, where would you rather the Garden of Eden be, in the great state of Missouri or in some hellhole in the Middle East?

In conclusion, I want to assure you all, lest there be any doubt, that I share your vision for this country and for the future of our world. Some say that we should focus on things like energy security, wealth inequality, epidemic disease, global climate change, nuclear proliferation, genocide, and other complex problems for which scientific knowledge, rational discussion, and secular politics are the best remedy. But you and I know that the problem we face is deeper and simpler and far more challenging. Since time immemorial humanity has been misled by Satan, the Father of Lies.

I trust we understand one another better now. And I hope you know how honored I will be to represent our party in the coming Presidential election.

God bless this great land, the United States of America.

January 5, 2012

The Free Will Delusion

The Free Will Delusion

January 3, 2012

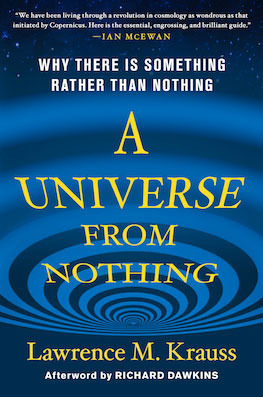

Everything and Nothing

Lawrence M. Krauss is a renowned cosmologist, popularizer of science, and director of the Origins Project at Arizona State University. He is the author of more than 300 scientific publications and 8 books, including the bestselling The Physics of Star Trek. His interests include the early universe, the nature of dark matter, general relativity and neutrino astrophysics. He is also a friend and an advisor to my nonprofit foundation, Project Reason. Lawrence generously took time to answer a few questions about his new book, A Universe from Nothing.

One of the most common justifications for religious faith is the idea that the universe must have had a creator. You've just written a book alleging that a universe can arise from "nothing." What do you mean by "nothing" and how fully does your thesis contradict a belief in a Creator God?

Indeed, the question, "Why is there something rather than nothing?" which forms the subtitle of the book, is often used by the faithful as an unassailable argument that requires the existence of God, because of the famous claim, "out of nothing, nothing comes." While the chief point of my book is to describe for the interested layperson the remarkable revolutions that have taken place in our understanding of the universe over the past 50 years—revolutions that should be celebrated as pinnacles of our intellectual experience—the second goal is to point out that this long-held theological claim is spurious. Modern science has made the something-from-nothing debate irrelevant. It has changed completely our conception of the very words "something" and "nothing". Empirical discoveries continue to tell us that the Universe is the way it is, whether we like it or not, and 'something' and 'nothing' are physical concepts and therefore are properly the domain of science, not theology or philosophy. (Indeed, religion and philosophy have added nothing to our understanding of these ideas in millennia.) I spend a great deal of time in the book detailing precisely how physics has changed our notions of "nothing," for example. The old idea that nothing might involve empty space, devoid of mass or energy, or anything material, for example, has now been replaced by a boiling bubbling brew of virtual particles, popping in and out of existence in a time so short that we cannot detect them directly. I then go on to explain how other versions of "nothing"—beyond merely empty space—including the absence of space itself, and even the absence of physical laws, can morph into "something." Indeed, in modern parlance, "nothing" is most often unstable. Not only can something arise from nothing, but most often the laws of physics require that to occur.

Now, having said this, my point in the book is not to suggest that modern science is incompatible with at least the Deistic notion that perhaps there is some purpose to the Universe (even though no such purpose is manifest on the basis of any of our current knowledge, and moreover there is no logical connection between any possible "creator" and the personal God of the world's major religions, who cares about humanity's destiny). Rather, what I find remarkable is the fact that the discoveries of modern particle physics and cosmology over the past half century allow not only a possibility that the Universe arose from nothing, but in fact make this possibility increasingly plausible. Everything we have measured about the universe is not only consistent with a universe that came from nothing (and didn't have to turn out this way!), but in fact, all the new evidence makes this possibility ever more likely. Darwin demonstrated how the remarkable diversity of life on Earth, and the apparent design of life, which had been claimed as evidence for a caring God, could in fact instead be arrived at by natural causes involving purely physical processes of mutation and natural selection. I want to show something similar about the Universe. We may never prove by science that a Creator is impossible, but, as Steven Weinberg has emphasized, science admits (and for many of us, suggests) a universe in which one is not necessary.

I cannot hide my own intellectual bias here. As I state in the first sentence of the book, I have never been sympathetic to the notion that creation requires a creator. And like our late friend, Christopher Hitchens, I find the possibility of living in a universe that was not created for my existence, in which my actions and thoughts need not bend to the whims of a creator, far more enriching and meaningful than the other alternative. In that sense, I view myself as an anti-theist rather than an atheist.

I'd like to linger on the concept of "nothing" for a moment, because I find it interesting. You have described three gradations of nothing—empty space, the absence of space, and the absence of physical laws. It seems to me that this last condition—the absence of any laws that might have caused or constrained the emergence of matter and space-time—really is a case of "nothing" in the strictest sense. It strikes me as genuinely incomprehensible that anything—laws, energy, etc.—could spring out of it. I don't mean to suggest that conceivability is a guide to possibility—there may be many things that happen, or might happen, which we are not cognitively equipped to understand. But the emergence of something from nothing (in this final sense) does strike me as a frank violation of the categories of human thought (akin to asserting that the universe is a round square), or the mere declaration of a miracle. Is there any

reason to believe that such nothing was ever the case? Might it not be easier to think about the laws of physics as having always existed?

That's a very good question, and it actually strikes to the heart of one of the things I wanted to stress most in the book. Because a frank violation of the categories of human thought is precisely what the Universe does all of the time. Quantum mechanics, which governs the behavior of our Universe on very small scales, is full of such craziness, which defies common sense in the traditional sense. So small squares are sometimes round.. namely systems can be in many different states at the same time, including ones which are mutually exclusive! Crazy, I know, but true… That is the heart of why the quantum universe is so weird. So, yes, it would be easier to think about the laws of physics as always having existed, but "easy" does not always coincide with "true." Once again, my mantra: The Universe is the way it is, whether we like it or not.

Now to hit the second part of your question… do we have any reason to suppose the laws themselves came into existence along with our universe? Yes… current ideas coming from particle physics allow a number of possibilities for multiple universes, in each of which some of the laws of physics, at least, would be unique to that universe. Now, do we have any models where all the laws (including even, say, quantum mechanics?) came into being along with the universe? No. But we know so little about the possibilities that this certainly remains one of them.

But even more germane to your question perhaps… do we have any physical reason to believe that such nothing was ever the case? Absolutely, because we are talking about our universe, and that doesn't preclude our universe arising from precisely nothing, embedded in a perhaps infinite space, or infinite collection of spaces, or spaces-to-be, some of which existed before ours came into being, and some of which are only now coming into, or going out of existence. In this sense, the multiverse, as it has become known, could be eternal, which certainly addresses one nagging aspect of the issue of First Cause.

I want to keep following this line, because it seems to me that we rarely do it—and I think many people will be interested to learn how a physicist like yourself views the foundations of science. As you know, in every branch of science apart from physics we stand upon an inherited set of concepts and laws that explain the whole enterprise. In neuroscience, for instance, we inherit the principles of chemistry and physics, and these explain everything from the behavior of neurons to the operation of our imaging tools. As one moves "up" in science, the problems become more complex (and for this reason the science inevitably gets "softer"), and we find very little reason to contemplate the epistemological underpinnings of science itself. So I'd like you to briefly tell us how you and your colleagues view the fact that certain descriptions of reality might be true, and testable, but impossible to understand. I had thought, for instance, that most physicists were unsatisfied with the strangeness of QM and still held out hope that a more fundamental theory would put things right, yielding a picture of reality that we could truly grasp, rather than merely accede to. Is that not true?

Another deep and difficult question Sam! A full answer would probably take more room than we have here, and I have tried to address this issue to some extent both in A Universe from Nothing and my books Fear of Physics and Hiding in the Mirror. First of all, let me address the issue of "understanding." There are aspects of the universe, such as the fact that three-dimensional space can be curved, which cannot be "understood" in an intuitive sense because we are three-dimensional beings. Just like the two-dimensional beings in the famous book Flatland, who had no idea how to truly picture a sphere, we cannot visualize a three-dimensional closed universe, for example. This does not stop us, however, from developing mathematics that completely describes such a universe. So, our mathematics can model such a universe and allow us to make predictions we can test, and therefore provide an "explanation" of the universe that is comprehensible, even if not intuitively understandable.

But there is something even more profound about the nature of "scientific truth" that has arisen in physics, which I don't think is generally appreciated. It is the simple fact that we realize that none of our theories are "true" in the sense that they adequately describe nature on all scales. All of our physical theories, as we now understand them, have limited domains of validity, which we can actually quantify in an accurate way. Even Quantum Electrodynamics, which is the best tested theory in nature, allowing us to predict the energy levels of atoms to better than 1 part in a billion, gets subsumed in a more general theory, called the Electroweak theory, when it is applied to trying to understand the interactions of quarks and electrons on scales 100 times smaller than the size of protons. Now, as Richard Feynman emphasized, we have no idea if this process will continue, if we will peel back the layers of reality like an onion, whether the process will never end, or whether we will truly come up with a fundamental theory that allows us to extrapolate our understanding to all scales. As he pointed out, it doesn't really matter, because what we scientists want to do is learn about how the universe works, and at each stage we learn something new. We may hope the universe has some fundamental explanation, but as I keep emphasizing, the universe is the way it is, whether we like it or not, and our job is to be brave enough to keep trying to understand it better, and to accept the reality that nature imposes upon us.

It is true that some physicists find the strangeness of Quantum Mechanics unsatisfying and suspect that it might be embedded in a more fundamental theory that seems less crazy. But hope and reality are not the same thing. Similarly, it may be intellectually unsatisfying to imagine that time began with our universe, so asking what came before is not a sensible question, or to imagine an eternal multiverse which itself was never created, or to never be able to empirically address the question of whether the laws of nature arose spontaneously along with the universe, but we have to keep plugging away regardless, motivated by the remarkable fact that nature has surprises in store for us that we never would have imagined!

Finally, it is the "how" question that is really most important, as I emphasize in the new book. Whenever we ask "why?" we generally mean "How?", because why implies a sense of purpose that we have no reason to believe actually exists. When we ask "Why are there 8 planets orbiting the Sun?" we really mean "How are there 8 planets?"—namely how did the evolution of the solar system allow the formation and stable evolution of 8 large bodies orbiting the Sun. And thus, as I also emphasize, we may never be able to discern if there is actually some underlying universal purpose to the universe, although there is absolutely no scientific evidence of such purpose at this point, what is really important to understanding ourselves and our place in the universe is not trying to parse vague philosophical questions about something and nothing, but rather to try and operationally understand how our universe evolved, and what the future might bring. Progress in physics in the past century has taken us to the threshold of addressing questions we might never have thought were approachable within the domain of science. We may never fully resolve them, but the very fact that we can plausibly address them is worth celebrating. That is the purpose of my book. And it is this intellectual quest that I find so very exciting, and which I want to share more broadly, because it represents to me the very best about what it means to be human.

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9007 followers