Sam Harris's Blog, page 32

August 29, 2011

Whither Eagleman?

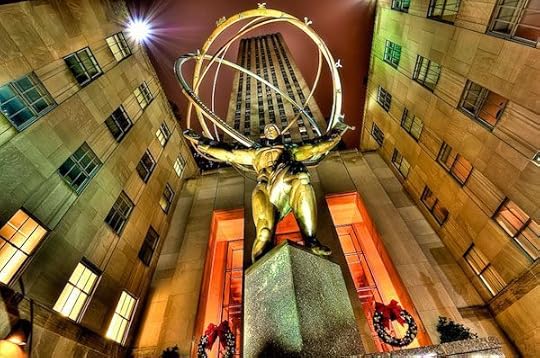

(Photo by Giampaolo Macorig)

I recently posted a TEDx talk by the neuroscientist David Eagleman, author of Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain and the subject of a recent profile in The New Yorker. While I admire much of what Eagleman has to say, I wrote that his espousal of "possibilianism," in lieu of atheism, was

August 27, 2011

The New Atheism

By James Wood

In the last 10 years or so, the rise of American evangelicalism and the menace of Islamist fundamentalism, along with developments in physics and in theories of evolution and cosmogony, have encouraged a certain style of aggressive, often strident atheistic critique.

August 24, 2011

How to Lose Readers (Without Even Trying)

(Photo by Francisco Diez)

Do you have too many readers of your books and articles? Want to reduce traffic on your blog? It turns out, there is a foolproof way to alienate many of your fans, quickly and at almost no cost.

It took me years to discover this publishing secret, but I'll pass it along to you for free:

Simply write an article suggesting that taxes should be raised on billionaires.

Really, it's that simple!

You can declare the world's religions to be cesspools of confusion and bigotry, you can argue that all drugs should be made legal and that free will is an illusion. You can even write in defense of torture. But I assure you that nothing will rile and winnow your audience like the suggestion that billionaires should contribute more of their wealth to the good of society.

This is not to say that everyone hated my last article ("How Rich is Too Rich?"), but the backlash has been ferocious. For candor and concision this was hard to beat:

You are scum sam. unsubscribed.

Unlike many of the emails I received, this one made me laugh out loud—for rarely does one see the pendulum of human affection swing so freely. Note that this response came, not from a mere visitor to my blog, but from someone who had once admired me enough to subscribe to my email newsletter. All it took was a single article about the problem of wealth inequality to provoke, not just criticism, but loathing.

The following should indicate the general gloom that has crept over my inbox:

I will not waste my time addressing your nonsense point-by-point, but I certainly could and I think in a more informed way than many economists—whose credentials you seem to think are necessary for your consideration of a response. Do you see what an elitist ass that makes you seem? I think you should stick to themes you know something about such as how unreasonable religion is. I am sure I am not the only one whose respect you lose with your economic ideology.

Nothing illustrates why people should not leave their comfort zones than this egregiously silly piece….You make such good points about the importance of skeptical inquiry and about how difficult it is to truly know something that your soak the rich comments are, as a good man once said, not even wrong. Take care.

Sorry Sam. I used to praise and promote your works. You've lost me. Your promotion of theft by initiating force on others is unforgivable. You're just a thug now, attempting cheap personal gratification by broadcasting signals which cost you nothing, just like Warren Buffett.

Many readers were enraged that I could support taxation in any form. It was as if I had proposed this mad scheme of confiscation for the first time in history. Several cited my framing of the question—"how much wealth can one person be allowed to keep?"—as especially sinister, as though I had asked, "how many of his internal organs can one person be allowed to keep?"

For what it's worth—and it won't be worth much to many of you—I understand the ethical and economic concerns about taxation. I agree that everyone should be entitled to the fruits of his or her labors and that taxation, in the State of Nature, is a form of theft. But it appears to be a form of theft that we require, given how selfish and shortsighted most of us are.

Many of my critics imagine that they have no stake in the well-being of others. How could they possibly benefit from other people getting first-rate educations? How could they be harmed if the next generation is hurled into poverty and despair? Why should anyone care about other people's children? It amazes me that such questions require answers.

Would Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, rather have $10 billion in a country where the maximum number of people are prepared to do creative work? Or would he rather have $20 billion in a country with the wealth inequality of an African dictatorship and commensurate levels of crime?[] I'd wager he would pick door number #1. But if he wouldn't, I maintain that it is only rational and decent for Uncle Sam to pick it for him.

However, many readers view this appeal to State power as a sacrilege. It is difficult to know what to make of this. Either they yearn for reasons to retreat within walled compounds wreathed in razor wire, or they have no awareness of the societal conditions that could warrant such fear and isolation. And they consider any effort the State could take to prevent the most extreme juxtaposition of wealth and poverty to be indistinguishable from Socialism.

It is difficult to ignore the responsibility that Ayn Rand bears for all of this. I often get emails from people who insist that Rand was a genius—and one who has been unfairly neglected by writers like myself. I also get emails from people who have been "washed in the blood of the Lamb," or otherwise saved by the "living Christ," who have decided to pray for my soul. It is hard for me to say which of these sentiments I find less compelling.

As someone who has written and spoken at length about how we might develop a truly "objective" morality, I am often told by followers of Rand that their beloved guru accomplished this task long ago. The result was Objectivism—a view that makes a religious fetish of selfishness and disposes of altruism and compassion as character flaws. If nothing else, this approach to ethics was a triumph of marketing, as Objectivism is basically autism rebranded. And Rand's attempt to make literature out of this awful philosophy produced some commensurately terrible writing. Even in high school, I found that my copies of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged simply would not open.

And I say this as someone who considers himself, in large part, a "libertarian"—and who has, therefore, embraced more or less everything that was serviceable in Rand's politics. The problem with pure libertarianism, however, has long been obvious: We are not ready for it. Judging from my recent correspondence, I feel this more strongly than ever. There is simply no question that an obsession with limited government produces impressive failures of wisdom and compassion in otherwise intelligent people.

Why do we have laws in the first place? To prevent adults from behaving like dangerous children. All laws are coercive and take the following form: do this, and don't do that, or else. Or else what? Or else men with guns will arrive at your door and take you away to prison. Yes, it would be wonderful if we did not need to be corralled and threatened in this way. And many uses of State power are both silly and harmful (the "war on drugs" being, perhaps, the ultimate instance). But the moment certain strictures are relaxed, people reliably go berserk. And we seem unable to motivate ourselves to make the kinds of investments we should make to create a future worth living in. Even the best of us tend to ignore some of the more obvious threats to our long term security.

For instance, Graham Alison, author of Nuclear Terrorism, thinks there is a greater than 50 percent chance that a nuclear bomb will go off in an American city sometime in the next ten years. (A poll of national security experts commissioned by Senator Richard Lugar in 2005 put the risk at 29 percent.) The amount of money required to secure the stockpiles of weapons and nuclear materials in the former Soviet Union is a pittance compared to the private holdings of the richest Americans. And should even a single incident of nuclear terrorism occur, the rich would likely lose more money in the resulting economic collapse than would have been required to secure the offending materials in the first place.

If private citizens cannot be motivated to allocate the necessary funds to mitigate such problems—as it seems we cannot—the State must do it. The State, however, is broke.

And lurking at the bottom of this morass one finds flagrantly irrational ideas about the human condition. Many of my critics pretend that they have been entirely self-made. They seem to feel responsible for their intellectual gifts, for their freedom from injury and disease, and for the fact that they were born at a specific moment in history. Many appear to have absolutely no awareness of how lucky one must be to succeed at anything in life, no matter how hard one works. One must be lucky to be able to work. One must be lucky to be intelligent, to not have cerebral palsy, or to not have been bankrupted in middle age by the mortal illness of a spouse.

Many of us have been extraordinarily lucky—and we did not earn it. Many good people have been extraordinarily unlucky—and they did not deserve it. And yet I get the distinct sense that if I asked some of my readers why they weren't born with club feet, or orphaned before the age of five, they would not hesitate to take credit for these accomplishments. There is a stunning lack of insight into the unfolding of human events that passes for moral and economic wisdom in some circles. And it is pernicious. Followers of Rand, in particular, believe that only a blind reliance on market forces and the narrowest conception of self interest can steer us collectively toward the best civilization possible and that any attempt to impose wisdom or compassion from the top—no matter who is at the top and no matter what the need—is necessarily corrupting of the whole enterprise. This conviction is, at the very least, unproven. And there are many reasons to believe that it is dangerously wrong.

Given the current condition of the human mind, we seem to need a State to set and enforce certain priorities. I share everyone's concern that our political process is broken, that it can select for precisely the sorts of people one wouldn't want in charge, and that fantastic sums of money get squandered. But no one has profited more from our current system, with all its flaws, than the ultra rich. They should be the last to take their money off the table. And they should be the first to realize when more resources are necessary to secure the common good.

In reply to my question about future breakthroughs in technology (e.g. robotics, nanotech) eliminating millions of jobs very quickly, and creating a serious problem of unemployment, the most common response I got from economists was some version of the following:

1. There ***IS*** a fundamental principle of economics that rules out a serious long-term problem of unemployment:

The first principle of economics is that we live in a world of scarcity, and the second principle of economics is that we have unlimited wants and desires.

Therefore, the second principle of economics: unlimited wants and desires, rules out long-term problem of unemployment.

2. What if we were having this discussion in the 1800s, when it was largely an agricultural-based economy, and you were suggesting that "future breakthroughs in farm technology (e.g. tractors, electricity, combines, cotton gin, automatic milking machinery, computers, GPS, hybrid seeds, irrigation systems, herbicides, pesticides, etc.) could eliminate millions of jobs, creating a serious problem of unemployment."

With hindsight, we know that didn't happen, and all of the American workers who would have been working on farms without those technological, labor-saving inventions found employment in different or new sectors of the economy like manufacturing, health care, education, business, retail, transportation, etc.

For example, 90% of Americans in 1790 were working in agriculture, and now that percentage is down to about 2%, even though we have greater employment overall now than in 1790. The technological breakthroughs reduced the share of workers in farming, but certainly didn't create long-term problems of unemployment. Thanks to "unlimited wants and desires," Americans found gainful employment in industries besides farming.

Mark J. Perry

Professor of Economics, University of Michigan, Flint campus and

Visiting Scholar at The American Enterprise Institute and

Carpe Diem Blog

As I wrote to several of these correspondents, I worry that the adjective "long-term" waves the magician's scarf a bit, concealing some very unpleasant possibilities. Are they so unpleasant that any rational billionaire who loves this country (and his grandchildren) would want to avoid them at significant cost in the near term? I suspect the answer could be "yes."

Also, it seemed to me that many readers aren't envisioning just how novel future technological developments might be. The analogy to agriculture doesn't strike me as very helpful. The moment we have truly intelligent machines, the pace of innovation could be extraordinarily steep, and the end of drudgery could come quickly. In a world without work everyone would be free—but, in our current system, some would be free to starve.

However, at least one reader suggested that the effect of truly game-changing nanotechnology or AI could not concentrate wealth, because its spread would be uncontainable, making it impossible to enforce intellectual property laws. The resultant increases in wealth would be free for the taking. This is an interesting point. I'm not sure it blocks every pathway to pathological concentrations of wealth—but it offers a ray of hope I hadn't seen before. It is interesting to note, however, what a strange hope it is: The technological singularity that will redeem human history is, essentially, Napster.

Fewer people wanted to tackle the issue of an infrastructure bank. Almost everyone who commented on this idea supported it, but many thought either (1) that it need not be funded now (i.e. We should take on more debt to pay for it) or (2) that if funded, it must be done voluntarily.

It was disconcerting how many people felt the need to lecture me about the failure of Socialism. To worry about the current level of wealth inequality is not to endorse Socialism, or to claim that the equal distribution of goods should be an economic goal. I think a certain level of wealth inequality is probably a very good thing—being both reflective and encouraging of differences between people that should be recognized and rewarded. There are people who can be motivated to work 100 hours a week by the prospect of getting rich, and they often accomplish goals that are very beneficial. And there are people who are simply incapable of making similar contributions to society. But do you really think that Steve Jobs would have retired earlier if he knew that all the wealth he acquired beyond $5 billion would be taxed at 90 percent? Many of people apparently do. However, I think they are being far too cynical about the motivations of smart, creative people.

Finally, many readers said something like the following:

If you or Warren Buffett want to pay more in taxes, go ahead. You are perfectly free to write the Treasury a check. And if you haven't done this, you're just a hypocrite.

Few people are eager to make large, solitary, and ineffectual sacrifices. And I was not arguing that the best use of Buffett's wealth would be for him to simply send it to the Treasury so that the government could use it however it wanted. I believe the important question is, how can we get everyone with significant resources to put their shoulders to the wheel at the same moment so that large goals get accomplished?

Imagine opening the newspaper tomorrow and discovering that Buffett had convened a meeting of the entire Forbes 400 list, and everyone had agreed to put 50 percent of his or her wealth toward crucial infrastructure improvements and the development of renewable energy technologies. I would like to believe that we live in a world where such things could happen—because, increasingly, it seems that we live in a world where such things must happen.

What can be done to bridge this gap?

August 17, 2011

How Rich is Too Rich?

(Photo by Stuck in Customs)

I've written before about the crisis of inequality in the United States and about the quasi-religious abhorrence of "wealth redistribution" that causes many Americans to oppose tax increases, even on the ultra rich. The conviction that taxation is intrinsically evil has achieved a sadomasochistic fervor in conservative circles—producing the Tea Party, their Republican zombies, and increasingly terrifying failures of governance.

Happily, not all billionaires are content to hoard their money in silence. Earlier this week, Warren Buffett published an op-ed in the New York Times in which he criticized our current approach to raising revenue. As he has lamented many times before, he is taxed at a lower rate than his secretary is. Many conservatives pretend not to find this embarrassing.

Conservatives view taxation as a species of theft—and to raise taxes, on anyone for any reason, is simply to steal more. Conservatives also believe that people become rich by creating value for others. Once rich, they cannot help but create more value by investing their wealth and spawning new jobs in the process. We should not punish our best and brightest for their success, and stealing their money is a form of punishment.

Of course, this is just an economic cartoon. We don't have perfectly efficient markets, and many wealthy people don't create much in the way of value for others. In fact, as our recent financial crisis has shown, it is possible for a few people to become extraordinarily rich by wrecking the global economy.

Nevertheless, the basic argument often holds: Many people have amassed fortunes because they (or their parent's, parent's, parents) created value. Steve Jobs resurrected Apple Computer and has since produced one gorgeous product after another. It isn't an accident that millions of us are happy to give him our money.

But even in the ideal case, where obvious value has been created, how much wealth can one person be allowed to keep? A trillion dollars? Ten trillion? (Fifty trillion is the current GDP of Earth.) Granted, there will be some limit to how fully wealth can concentrate in any society, for the richest possible person must still spend money on something, thereby spreading wealth to others. But there is nothing to prevent the ultra rich from cooking all their meals at home, using vegetables grown in their own gardens, and investing the majority of their assets in China.

Bill Gates and Warren Buffet, the two richest men in the United States, each have around $50 billion. Let's put this number in perspective: They each have a thousand times the amount of money you would have if you were a movie star who had managed to save $50 million over the course of a very successful career. Think of every actor you can name or even dimly recognize, including the rare few who have banked hundreds of millions of dollars in recent years, and run this highlight reel back half a century. Gates and Buffet each have more personal wealth than all of these glamorous men and women—from Bogart and Bacall to Pitt and Jolie—combined.

In fact, there are people who rank far below Gates and Buffet in net worth, who still make several million dollars a day, every day of the year, and have throughout the current recession.

And there is no reason to think that we have reached the upper bound of wealth inequality, as not every breakthrough in technology creates new jobs. The ultimate labor saving device might be just that—the ultimate labor saving device. Imagine the future Google of robotics or nanotechnology: Its CEO could make Steve Jobs look like a sharecropper, and its products could put tens of millions of people out of work. What would it mean for one person to hold the most valuable patents compatible with the laws of physics and to amass more wealth than everyone else on the Forbes 400 list combined?

How many Republicans who have vowed not to raise taxes on billionaires would want to live in a country with a trillionaire and 30 percent unemployment? If the answer is "none"—and it really must be—then everyone is in favor of "wealth redistribution." They just haven't been forced to admit it.

Yes, we must cut spending and reduce inefficiencies in government—and yes, many things are best accomplished in the private sector. But this does not mean that we can ignore the astonishing gaps in wealth that have opened between the poor and the rich, and between the rich and the ultra rich. Some of your neighbors have no more than $2,000 in total assets (in fact, 40 percent of Americans fall into this category); some have around $2 million; and some have $2 billion (and a few have much more). Each of these gaps represents a thousandfold increase in wealth.

Some Americans have amassed more wealth than they or their descendants can possibly spend. Who do conservatives think is in a better position to help pull this country back from the brink?

August 15, 2011

COMING IN SEPTEMBER:

August 11, 2011

Ask Sam Harris Anything #2

The full video is an hour long. Links to specific topics/questions are provided below:

1. Eternity and the meaning of life 0:42

2. Do we have free will? 4:43

3. How can we convince religious people to abandon their beliefs? 14:52

4. How can atheists live among the faithful? 19:09

5. How should we talk to children about death? 21:52

6. Does human life have intrinsic value? 26:01

7. Why should we be confident in the authority of science? 30:36

8. How can one criticize Islam after the terrorism in Norway? 35:43

9. Should atheists join with Christians against Islam? 41:50

10. What does it mean to speak about the human mind objectively? 45:17

11. How can spiritual claims be scientifically justified? 50:14

12. Why can't religion remain a private matter? 54:52

13. What do you like to speak about at public events? 58:09

August 7, 2011

The Truth About the Vatican

Finally, a head of state speaks the truth about the Vatican. This is a wonderfully honest speech by Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny.

For those who missed my previous essay on the crimes of the Catholic Church:

Bringing the Vatican to Justice

July 28, 2011

Faith No More

Earlier this year, Andrew Zak Williams asked public figures why they believe in God. Now it's the turn of the atheists. Philip Pullman, Richard Dawkins, Stephen Hawking, Steven Weinberg, Roger Penrose, and others respond.

July 26, 2011

Dear Angry Lunatic: A Response to Chris Hedges

(Photo by H.koppdelaney)

Over at Truthdig, the celebrated journalist Chris Hedges has discovered that Christopher Hitchens and I are actually racists with a fondness for genocide. He has broken this story before—many times, in fact—but in his most recent essay he blames "secular fundamentalists" like me and Hitch for the recent terrorist atrocities in Norway.

Very nice.

Hedges begins, measured as always:

The gravest threat we face from terrorism, as the killings in Norway by Anders Behring Breivik underscore, comes not from the Islamic world but the radical Christian right and the secular fundamentalists who propagate the bigoted, hateful caricatures of observant Muslims and those defined as our internal enemies. The caricature and fear are spread as diligently by the Christian right as they are by atheists such as Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens. Our religious and secular fundamentalists all peddle the same racist filth and intolerance that infected Breivik. This filth has poisoned and degraded our civil discourse. The looming economic and environmental collapse will provide sparks and tinder to transform this coarse language of fundamentalist hatred into, I fear, the murderous rampages experienced by Norway. I worry more about the Anders Breiviks than the Mohammed Attas.

The editors at Truthdig have invited me to respond to this phantasmagoria. There is, however, almost no charge worth answering in Hedges' writing—there never is. Which is more absurd, the idea of "secular fundamentalism" or the notion that its edicts pose a greater threat of terrorism than the doctrine of Islam? Do such assertions even require sentences to refute?

However, Hedges' latest attack is so vicious and gratuitous that some reply seemed necessary. To minimize the amount of time I would need to spend today cleaning this man's vomit, I decided to adapt a few pieces I had already written. But then I just got angry…

I sent the following to Truthdig:

****

After my first book was published, the journalist Chris Hedges seemed to make a career out of misrepresenting its contents—asserting, among other calumnies, that somewhere in its pages I call for an immediate, nuclear first strike on the entire Muslim world. Hedges spread this lie so sedulously that I could have spent years writing letters to the editor. Even if I had been willing to squander my time in this way, such letters are generally pointless, as few people read them. In the end, I decided to create a page on my website addressing such controversies, so that I can then forget all about them. The result has been less than satisfying. Several years have passed, and I still meet people at public talks and in comment threads who believe that I support the outright murder of hundreds of millions of innocent people.

In an apparent attempt to become the most tedious person on Earth, Hedges has attacked me again on this point, and the editors at Truthdig have invited me to respond. I suppose it is worth a try. To begin, I'd like to simply cite the text that has been on my website for years, so that readers can appreciate just how unscrupulous and incorrigible Hedges is:

The journalist Chris Hedges has repeatedly claimed (in print, in public lectures, on the radio, and on television) that I advocate a nuclear first-strike on the Muslim world. His remarks, which have been recycled continuously in interviews and blog-posts, generally take the following form:

"I mean, Sam Harris, at the end of his first book, asks us to consider a nuclear first strike on the Arab world." (Q&A at Harvard Divinity School, March 20, 2008)

"Harris, echoing the blood lust of [Christopher] Hitchens, calls, in his book 'The End of Faith,' for a nuclear first strike against the Islamic world." ("The Dangerous Atheism of Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris," AlterNet, March 22, 2008)

"And you have in Sam Harris' book, 'The End of Faith,' a call for us to consider a nuclear first strike against the Arab world. This isn't rational. This is insane." ("The Tavis Smiley Show," April 15, 2008)

"Sam Harris, in his book 'The End of Faith,' asks us to consider carrying out a nuclear first-strike on the Arab world. That's not a rational option—that's insanity." ("A Conversation with Chris Hedges," Free Inquiry, August/September 2008)

Wherever they appear, Hedges' comments seem calculated to leave the impression that I want the U.S. government to start killing Muslims by the millions. Below I present the only passage I have ever written on the subject of preventative nuclear war and the only passage that Hedges could be referring to in my work ("The End of Faith," pages 128-129). I have taken the liberty of emphasizing some of the words that Hedges chose to ignore:

It should be of particular concern to us that the beliefs of Muslims pose a special problem for nuclear deterrence. There is little possibility of our having a cold war with an Islamist regime armed with long-range nuclear weapons. A cold war requires that the parties be mutually deterred by the threat of death. Notions of martyrdom and jihad run roughshod over the logic that allowed the United States and the Soviet Union to pass half a century perched, more or less stably, on the brink of Armageddon. What will we do if an Islamist regime, which grows dewy-eyed at the mere mention of paradise, ever acquires long-range nuclear weaponry? If history is any guide, we will not be sure about where the offending warheads are or what their state of readiness is, and so we will be unable to rely on targeted, conventional weapons to destroy them. In such a situation, the only thing likely to ensure our survival may be a nuclear first strike of our own. Needless to say, this would be an unthinkable crime—as it would kill tens of millions of innocent civilians in a single day—but it may be the only course of action available to us, given what Islamists believe. How would such an unconscionable act of self-defense be perceived by the rest of the Muslim world? It would likely be seen as the first incursion of a genocidal crusade. The horrible irony here is that seeing could make it so: this very perception could plunge us into a state of hot war with any Muslim state that had the capacity to pose a nuclear threat of its own. All of this is perfectly insane, of course: I have just described a plausible scenario in which much of the world's population could be annihilated on account of religious ideas that belong on the same shelf with Batman, the philosopher's stone, and unicorns. That it would be a horrible absurdity for so many of us to die for the sake of myth does not mean, however, that it could not happen. Indeed, given the immunity to all reasonable intrusions that faith enjoys in our discourse, a catastrophe of this sort seems increasingly likely. We must come to terms with the possibility that men who are every bit as zealous to die as the nineteen hijackers may one day get their hands on long-range nuclear weaponry. The Muslim world in particular must anticipate this possibility and find some way to prevent it. Given the steady proliferation of technology, it is safe to say that time is not on our side.

I will let the reader judge whether this award-winning journalist has represented my views fairly.

I hope Truthdig readers appreciate the irony here. In his latest fever dream of an essay, Hedges declares that Christopher Hitchens and I (along with our pals on the Christian right) are incapable of "nuance." Amazing. Nuance is really what one hopes Hedges would discover once in his life—if for no other reason than it would leave him with nothing left to say.

I don't think I have ever met anyone so determined to live as a Freudian case study: To read any page of Hedges' is to witness the full catastrophe of public self-deception. He rages (and rages) about the anger and intolerance of others; he accuses his opponents of being "immune to critiques based on reason, fact and logic" in prose so bloated with emotion and insult, and so barren of argument, that every essay reads like a hoax text meant to embarrass the humanities. A person with this little self-awareness should be given a mirror—or an intervention—never a blog.

An editorial (rather than psychoanalytic) note: Hedges claims that I "abrogate the right to exterminate all who do not conform" to my rigid view of the world. I'm afraid this is true. I do, as it turns out, abrogate that right. But Hedges surely means to say that I "arrogate" it. Advice for future skirmishes, Chris: When you are going to insult your opponents by calling them "ignoramuses" who "cannot afford complexity," or disparage them for being incapable of "intellectual and scientific rigor," it is best to know the meanings of the words you use. Not all the words, perhaps—just those you grope for when calling someone a genocidal maniac.

Leaving no canard unemployed, Hedges accuses me of being a racist—again. In truth, he has raised the ante somewhat: My criticism of Islam is now "racist filth." It is tempting to own up to this charge just to see the uncomprehending look on his face: "You know, after a lot of additional study and soul-searching, I realized that you are right: My contention that the doctrines of martyrdom and jihad are integral to Islam, and dangerous, is really nothing more than racist filth. Sorry about that."

However, the response I offered years ago still seems in order:

Some critics of my work have claimed that my critique of Islam is "racist." This charge is almost too silly to merit a response. But, as prominent writers can sometimes be this silly, here goes:

My analysis of religion in general, and of Islam in particular, focuses on what I consider to be bad ideas, held for bad reasons, leading to bad behavior. My antipathy toward Islam—which is, in truth, difficult to exaggerate—applies to ideas, not to people, and certainly not to the color of a person's skin. My criticism of the logical and behavioral consequences of certain ideas (e.g. martyrdom, jihad, honor, etc.) impugns white converts to Islam—like Adam Gadahn—every bit as much as Arabs like Ayman al-Zawahiri. I am also in the habit of making invidious comparisons between Islam and other religions, like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Must I point out that most Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains are not white like me? One would hope there would be no such need—but the work of writers like Chris Hedges suggests that the need is pressing.

As I regularly emphasize when discussing Islam, no one is suffering under the doctrine of Islam more than Muslims are—particularly Muslim women. Those who object to any attack upon the religion of Islam as "racist" or as a symptom of "Islamophobia" display a nauseating insensitivity to the subjugation of women throughout the Muslim world. At this moment, millions of women and girls have been abandoned to illiteracy, forced marriage, and lives of slavery and abuse under the guise of "multiculturalism" and "religious sensitivity." This is a crime to which every apologist for Islam is now an accomplice.

I have participated in many debates over the years and engaged many of my critics. In fact, I once debated Hedges at a benefit for Truthdig. You can watch our exchange here. I am happy to say that these encounters are usually very pleasant—for even when they grow prickly on the stage, the exchange in the green room is generally quite warm. My meeting with Hedges was a notable exception. In fact, Hedges is the one person I have told event organizers that I will not appear with again for any reason—which is a pity, because his inability to present or follow an argument makes everything one says sound incisive. The man is not only wrong in his convictions, but dishonest—and determined to remain so. I trust this is a consequence of his most conspicuous quality as a person: sanctimony. There is a main vein of sanctimony in this universe, and it appears to run directly through the brain of Chris Hedges. He has staked his claim to it and will follow it wherever it leads. The results can be seen weekly on this page. And I'm sorry to say that this is why I stopped writing for Truthdig years ago.

July 24, 2011

Christian Terrorism and Islamophobia

At certain points near the extremity of human evil it becomes difficult, and perhaps pointless, to make ethical distinctions. However, I cannot shake the feeling that detonating a large bomb in the center of a peaceful city with the intent of killing vast numbers of innocent people was the lesser of Anders Behring Breivik's transgressions last week. It seems to me that it required greater malice, and even less humanity, to have intended this atrocity to be a mere diversion, so that he could then commit nearly one hundred separate murders on the tiny Island of Utoya later in the day.

And just when one thought the human mind could grow no more depraved, one learns details like the following:

After killing several people on one part of the island, he went to the other, and, dressed in his police uniform, calmly convinced the children huddled there that he meant to save them. When they emerged into the open, he fired again and again. ("For Young Campers, Island Turned Into Fatal Trap." The New York Times, July 23, 2011)

Other unsettling facts will surely surface in the coming weeks. Some might even be vaguely exculpatory. Is Breivik mentally ill? Judging from his behavior, it is difficult to imagine a definition of "sanity" that could contain him.

It has been widely reported that Breivik is a "Christian fundamentalist." Having read parts of his 1500-page manifesto (2083: A European Declaration of Independence), I must say that I have my doubts. These do not appear to be the ruminations of an especially committed Christian:

I'm not going to pretend I'm a very religious person as that would be a lie. I've always been very pragmatic and influenced by my secular surroundings and environment. In the past, I remember I used to think;

"Religion is a crutch for weak people. What is the point in believing in a higher power if you have confidence in yourself!? Pathetic."

Perhaps this is true for many cases. Religion is a crutch for many weak people and many embrace religion for self serving reasons as a source for drawing mental strength (to feed their weak emotional state f example during illness, death, poverty etc.). Since I am not a hypocrite, I'll say directly that this is my agenda as well. However, I have not yet felt the need to ask God for strength, yet… But I'm pretty sure I will pray to God as I'm rushing through my city, guns blazing, with 100 armed system protectors pursuing me with the intention to stop and/or kill. I know there is a 80%+ chance I am going to die during the operation as I have no intention to surrender to them until I have completed all three primary objectives AND the bonus mission. When I initiate (providing I haven't been apprehended before then), there is a 70% chance that I will complete the first objective, 40% for the second, 20% for the third and less than 5% chance that I will be able to complete the bonus mission. It is likely that I will pray to God for strength at one point during that operation, as I think most people in that situation would….If praying will act as an additional mental boost/soothing it is the pragmatical thing to do. I guess I will find out… If there is a God I will be allowed to enter heaven as all other martyrs for the Church in the past. (p. 1344)

As I have only read parts of this document, I cannot say whether signs of a deeper religious motive appear elsewhere in it. Nevertheless, the above passages would seem to undermine any claim that Breivik is a Christian fundamentalist in the usual sense. What cannot be doubted, however, is that Breivik's explicit goal was to punish European liberals for their timidity in the face of Islam.

I have written a fair amount about the threat that Islam poses to open societies, but I am happy to say that Breivik appears never to have heard of me. He has, however, digested the opinions of many writers who share my general concerns—Theodore Dalrymple, Robert D. Kaplan, Lee Harris, Ibn Warraq, Bernard Lewis, Andrew Bostom, Robert Spencer, Walid Shoebat, Daniel Pipes, Bat Ye'or, Mark Steyn, Samuel Huntington, et al. He even singles out my friend and colleague Ayaan Hirsi Ali for special praise, repeatedly quoting a blogger who thinks she deserves a Nobel Peace Prize. With a friend like Breivik, one will never want for enemies.

One can only hope that the horror and outrage provoked by Breivik's behavior will temper the growing enthusiasm for right-wing, racist nationalism in Europe. However, one now fears the swing of another pendulum: We are bound to hear a lot of deluded talk about the dangers of "Islamophobia" and about the need to address the threat of "terrorism" in purely generic terms.

The emergence of "Christian" terrorism in Europe does absolutely nothing to diminish or simplify the problem of Islam—its repression of women, its hostility toward free speech, and its all-too-facile and frequent resort to threats and violence. Islam remains the most retrograde and ill-behaved religion on earth. And the final irony of Breivik's despicable life is that he has made that truth even more difficult to speak about.

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9008 followers