Sam Harris's Blog, page 31

September 26, 2011

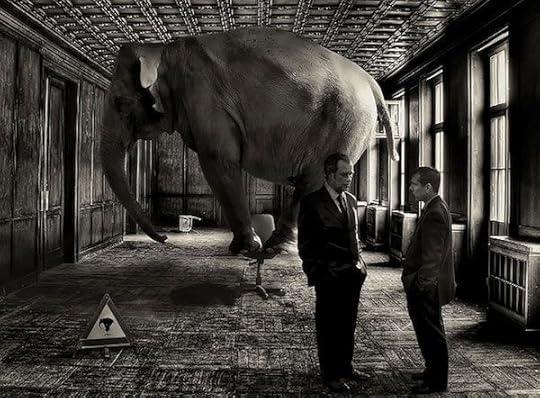

The Future of the Book

(Photo by David Blackwell)

Writers, artists, and public intellectuals are nearing some sort of precipice: Their audiences increasingly expect digital content to be free. Jaron Lanier has written and spoken about this issue with great sagacity. You can purchase his book here, which most of you will not do, or you can watch him discuss these matters for free. The problem is thus revealed even in the act of stating it. How can a person like Lanier get paid for being brilliant? This has become an increasingly difficult question to answer.

Where publishing is concerned, the Internet is both midwife and executioner. It has never been easier to reach large numbers of readers, but these readers have never felt more entitled to be informed and entertained for free. I have been very slow to appreciate these developments, and yet it is clear even to me that there are reasons to fear for the life of the printed book. Needless to say, many of the changes occurring in publishing are changes that neither publishers nor authors want. The market for books is continually shifting beneath our feet, and nobody knows what the business of publishing will look like a decade from now.

When I published The End of Faith in 2004, I created this website as an afterthought. In fact, I remember feeling silly asking my publisher to put the web address on the dust jacket, not knowing if there was any point in doing so. While my website has since become the hub of everything I have accomplished as an author, it took me years to understand its utility, and I only began blogging a few months ago. Clearly, I am a slow learner. But many other authors are still pretending that the Internet doesn't exist. Some will surely see their careers suffer as a result. One fact now seems undeniable: The future of the written word is (mostly or entirely) digital.

Journalism was the first casualty of this transformation. How can newspapers and magazines continue to make a profit? Online ads don't generate enough revenue and paywalls are intolerable; thus, the business of journalism is in shambles. Even though I sympathize with the plight of publishers—and share it by association as a writer—as a reader, I am without pity. If your content is behind a paywall, I will get my news elsewhere. I subscribe to the print edition of The New Yorker, but when I want to read one of its articles online, I find it galling to have to login and wrestle with its proprietary e-reader. The result is that I read and reference New Yorker articles far less frequently than I otherwise would. I've been a subscriber for 25 years, but The New Yorker is about to lose me. What can they do? I don't know. The truth is, I now expect their content to be free.

My friend Christopher Hitchens is a writer of truly incandescent prose whose career has been forged almost entirely in the context of print journalism. Among his many outlets, the most prominent has probably been Vanity Fair: a gorgeous, glossy magazine to which I also subscribe. Happily, Vanity Fair offers its content for free on its website. I visited the site a moment ago and read Hitch's latest: a very tender essay of praise for the work of Joan Didion — another wonderful writer who, I have just learned from Hitch, will soon publish a book about the tragic death of her daughter. This will be a follow up to The Year of Magical Thinking, her searing account of the loss of her husband. I will buy and read Didion's new book, just as I bought and read the last one, and I expect that it will be a bestseller. Hitch did his job and got paid. Didion will soon publish her book in hardcover and has already benefited from his review. All appears to be well in the Kingdom of Print.

However, with the gimlet eyes of a new blogger, I detect ominous portents of change. First, I see that Hitch's article has been featured on the Vanity Fair website for the better part of a week and has garnered only 813 Facebook likes and 75 Tweets. Many of my blog articles receive more engagement than this, some by nearly a factor of 10. No doubt this has something to do with the ratio of signal to noise: When readers come to a personal blog, they are more or less guaranteed to read what the author has written. How many people will find Hitch's article on the Vanity Fair website? Of course, it is prominently displayed on the home page, along with an arresting photo of Didion taken by Annie Leibovitz, one of the most famous photographers on earth. Presumably, Leibovitz had to go to Didion's apartment with a small crew to obtain this image. All of this creative work was paid for, one imagines, by print ads. But with respect to Hitch's interests as a writer, and Didion's as his subject, everything else in the current issue of Vanity Fair is noise. A glance at the online page rank of the magazine raises even greater concerns. I know bloggers—Tim Ferriss and Seth Godin, for instance—whose personal blogs get more traffic than the entire Vanity Fair website.

When I began writing the previous paragraph, I forwarded Hitch's article on Facebook and Twitter. Over 3000 people have since followed the link I sent, and we're up to 955 Facebook likes and 100 Tweets. I hesitate to read too much into these metrics, but it doesn't seem entirely crazy to wonder whether a significant percentage of the people who have read Hitch's essay in the last week read it in the last hour because I broadcast it on social media. I used to view this as a wonderful synergy—digital enables print; print points back to digital; and both thrive. I now consider it the death knell for traditional publishing.

Vanity Fair has a print circulation of around 1 million copies; the current issue has a fresh photo of Angelina Jolie on its cover; and Hitch is one of the best writers to ever draw breath. However, I'm reasonably sure that this blog post, or the next one, will reach more readers than his latest gem. For bloggers like Ferriss and Godin, the future arrived long ago: Publishing in Vanity Fair would be tantamount to burying their work. This is astounding. Given its range of content, and the costs of acquiring this content, a magazine like Vanity Fair should get much more traffic than any one person's blog. And this brings us back to the problem of money: Apart from my occasional use of a webmaster and a graphic designer, my blog employs no one—not even me. Where is all this heading? I can count on one finger the number of places where it is still obviously better for me to publish than on my own blog—the opinion page of The New York Times. But it's not so much better that I've been tempted to send them an article in the last few months. Is this just the hubris of the blogosphere? Maybe—but not for everyone and not for long.

Related difficulties are now looming for books. I love physical books as much as anyone. And when I really want to get a book into my brain, I now purchase both the hardcover and electronic editions. From the point of view of the publishing industry, I am the perfect customer. This also makes me a very important canary in the coal mine—and I'm here to report that I've begun to feel woozy. For instance, I've started to think that most books are too long, and I now hesitate before buying the next big one. When shopping for books, I've suddenly become acutely sensitive to the opportunity costs of reading any one of them. If your book is 600 pages long, you are demanding more of my time than I feel free to give. And if I could accomplish the same change in my view of the world by reading a 60-page version of your argument, why didn't you just publish a book this length instead?

The honest answer to this last question should disappoint everyone: Publishers can't charge enough money for 60-page books to survive; thus, writers can't make a living by writing them. But readers are beginning to feel that this shouldn't be their problem. Worse, many readers believe that they can just jump on YouTube and watch the author speak at a conference, or skim his blog, and they will have absorbed most of what he has to say on a given subject. In some cases this is true and suggests an enduring problem for the business of publishing. In other cases it clearly isn't true and suggests an enduring problem for our intellectual life.

These intersecting concerns have now led me to stratify my written work: I am currently writing a traditional, printed book for my mainstream publisher, the Free Press. At the other extreme, I do a lot of writing for free, almost entirely on my blog. In between working for free and working for my publisher, I've begun to experiment with self publishing short ebooks. Last week, I published LYING, my first installment in this genre. The results have been simultaneously thrilling and depressing.

My goal in LYING was to write a very accessible essay on an important topic that could be absorbed in one sitting. I know how revolutionary it is to be honest with everyone one meets—to refuse to shade the truth even slightly in business or in one's personal life—and I know how few people do this. LYING spells out my reasons for thinking that we would all be better off living this way.

The essay appears to have had its desired effect on many readers. But others were not satisfied. Some did not understand the format—a very short book that can be read in 40 minutes—and expected to get a much longer book for $1.99. Many wondered why it is available only as an ebook. Some fans of ebooks were powerfully aggrieved to find it available only on the Kindle platform—they own Nooks, or detest Amazon for one reason or another. However, the fact is that Amazon made it extraordinarily easy for me to do this; the Kindle Single is the perfect format for so short a book; and Kindle content can be read on every computer and almost any handheld device. I decided that it was not worth my time or other people's money to publish LYING elsewhere, or as a physical book.

On the surface, the launch of LYING has been a great success. It reached the #1 spot for Kindle Singles immediately and #9 for all Kindle content. It is amazing to finish writing, hit "upload," and watch one's work soar and settle, however briefly, above the vampire novels and diet books.

I would be lying, however, if I said that I wasn't stung by some of the early criticism. Some readers felt that a 9000-word essay was not worth $1.99, especially when they can read my 5000-word blog posts for free. It is true that I put a lot of work into many of my blog posts, but LYING took considerably longer to write than any of them. It is a deceptively simple book—and I made it simple for a reason. Some of my readers seem not to have appreciated this and prefer to follow me into my usual thickets of argument and detail. That's fine. But it is, nevertheless, painful to lose a competition with oneself, especially over a difference of $1.99.

One thing is certain: writers and public intellectuals must find a way to get paid for what they do—and the opportunities to do this are changing quickly. My current solution is to write longer books for a traditional press and publish short ebooks myself on Amazon. If anyone has any better ideas, please publish them somewhere—perhaps on a blog—and then send me a link. And I hope you get paid.

September 15, 2011

Is It Wrong to Lie?

As an undergraduate at Stanford I took a course called "The Ethical Analyst" that profoundly changed my life. It was taught by an extraordinarily gifted professor, Ronald A. Howard, and focused on a single question of practical ethics:

Is it wrong to lie?

At first glance, this may seem a scant foundation for an entire college course. After all, most people already know that lying is generally wrong—and they also know that some situations seem to warrant it.

One of the most fascinating things about this course, however, was how difficult it was to find examples of virtuous lies that could withstand Professor Howard's scrutiny. Even with Nazis at the door and Anne Frank in the attic, Howard always seemed to find truths worth telling and paths to even greater catastrophe that could be opened by lying.

I do not remember what I thought about lying before I took "The Ethical Analyst," but the course accomplished as close to a firmware upgrade of my brain as I have ever experienced. I came away convinced that lying, even about the smallest matters, needlessly damages personal relationships and public trust.

It would be hard to exaggerate what a relief it was to realize this. It's not that I had been in the habit of lying before taking Howard's course—but I now knew that endless forms of suffering and embarrassment could be easily avoided by simply telling the truth. And, as though for the first time, I saw the consequences of others' failure to live by this principle all around me.

This experience remains one of the clearest examples in my own life of the power of philosophical reflection. "The Ethical Analyst" affected me in ways that college courses seldom do: It made me a better person.

I hope to produce a similar effect in readers of LYING, my first ebook.

***

LYING has been published exclusively as a Kindle Single edition. Like other ebooks in this format, it is short enough to be read in one sitting. If you don't have a Kindle, you can read LYING using the Kindle Reader App on your iPad, iPhone, Blackberry, PC, or other device.

This essay is quite brilliant. (I was hoping it would be, so I wouldn't have to lie.) I honestly loved it from beginning to end. LYING is the most thought-provoking read of the year.

Ricky Gervais

Humans have evolved to lie well, and no doubt you've seen the social lubrication at work. In many cases, we might not think of it as a true "lie": perhaps a "white lie" once in a blue moon, the omission of a sensitive detail here and there, false encouragement of others when we see no benefit in dashing someone's hopes, and the list goes on. In LYING, Sam Harris demonstrates how to benefit from being brutally—but pragmatically—honest. It's a compelling little book with a big impact.

Tim Ferriss, angel investor and author of the #1 New York Times bestsellers, The 4-Hour Body and The 4-Hour Workweek

In this brief but illuminating work, Sam Harris applies his characteristically calm and sensible logic to a subject that affects us all—the human capacity to lie. And by the book's end, Harris compels you to lead a better life because the benefits of telling the truth far outweigh the cost of lies—to yourself, to others, and to society.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, Astrophysicist, American Museum of Natural History

September 12, 2011

The Silent Crowd

It is widely believed that Thomas Jefferson was terrified of public speaking. John Adams once said of him, "During the whole time I sat with him in Congress, I never heard him utter three sentences together." During his eight years in the White House, Jefferson seems to have limited his speechmaking to two inaugural addresses, which he simply read out loud "in so low a tone that few heard it."

I remember how relieved I was to learn this. To know that it was possible to succeed in life while avoiding the podium was very consoling—for about five minutes. The truth is that not even Jefferson could follow in his own footsteps today. It is now inconceivable that a person could become president of the United States through the power of his writing alone. To refuse to speak in public is to refuse a career in politics—and many other careers as well.

In fact, Jefferson would be unlikely to succeed as an author today. It used to be that a person could just write books and, if he were lucky, people would read them. Now he must stand in front of crowds of varying sizes and say that he has written these books—otherwise, no one will know that they exist. Radio and television interviews offer new venues for stage fright: Some shows put one in front of a live audience of a few hundred people and an invisible audience of millions. You cannot appear on The Daily Show holding a piece of paper and begin reading your lines like Thomas Jefferson.

Of course, it is possible to just write books and hope for the best, but refusing to speak in public is a good way to ensure that they will not be read. This iron law of marketing might relax somewhat for fiction—but even there, unless you are J.D. Salinger or Thomas Pynchon, remaining invisible is generally a path not to the literary firmament but to oblivion.

Fear of public speaking is also a fertile source of psychological suffering elsewhere in life. I can remember dreading any event where being asked to speak was a possibility. I have to give a toast at your wedding? Wonderful. I can now spend the entire ceremony, and much of the preceding week, feeling like a condemned man in view of the scaffold.

Pathological self-consciousness in front of a crowd is more than ordinary anxiety: it lies closer to the core of the self. It seems, in fact, to be the self—the very feeling we call "I"—but magnified grotesquely. There are few instances in life when the sense of being someone becomes so onerous. The experience is analogous to having a pain in your gut that lingers on the margins of awareness but seems impossible to pinpoint or describe—until you are supine on an examination table with a doctor probing your abdomen:

"Does that hurt?"

"No."

"How about there?"

"Not really."

"How about—"

"Ow!"

Yes, that's where it hurts. For one who is terrified of public speaking, standing in front of a crowd exploits the cramp of self in a similar way. Yes, that is the problem with being me. Ow… The feeling that we call "I"—the ghost that wears your face like a mask at this moment—seems to suddenly gather mass and become the site of a psychological implosion.

Of course, many people have solved the problem of what to do when a thousand pairs of eyes are looking their way. And some of them, for whatever reason, are natural performers. From childhood, they have wanted nothing more than to display their talents to a crowd. Many of these people are narcissists, of course, and hollowed out in unenviable ways. Where your self-consciousness has become a dying star, theirs has become a wormhole to a parallel universe. They don't suffer much there, perhaps, but they don't quite make contact here either. And many natural performers are comfortable only within a certain frame. It is always interesting, for instance, to see a famous actor wracked by fear while accepting an Academy Award. Simply being oneself before an audience can be terrifying even for those who perform for a living.

Needless to say, I am not a born performer. Nor am I naturally comfortable standing in front of a group of friends or strangers to deliver a message. However, I have always been someone who had things he wanted to say. This marriage of fear and desire is an unhappy one—and many people are stuck in it.

At the end of my senior year in high school, I learned that I was to be the class valedictorian. I declined the honor. And I managed to get into my thirties without directly confronting my fear of public speaking. At the age of thirty-three, I enrolled in graduate school, where I gave a few scientific presentations while lurking in the shadows of PowerPoint. Still, it seemed that I might be able to skirt my problem with a little luck—until I began to feel as though a large pit had opened in the center of my life, and I was circling the edge. It was becoming professionally and psychologically impossible to turn away.

The reckoning finally came when I published my first book, The End of Faith. Suddenly, I was thirty-seven and faced with the prospect of a book tour. I briefly considered avoiding all public appearances and becoming a man of mystery. Had I done so, I would still be fairly mysterious, and you probably wouldn't be reading these words.

I cannot personally attest to most forms of self-overcoming: I don't know what it is like to recover from addiction, lose a hundred pounds, or fight in a war. I can say from experience, however, that it is possible to change one's relationship to public speaking.

And the process need not take long. In fact, I have spoken publicly no more than fifty times in my life, and many of my earliest appearances were for fairly high stakes, being either televised, or against opponents who would have dearly loved to see me fail, or both. Given where I started, I believe that almost anyone can transcend a fear of the podium. (Whether he has something interesting to say is another matter, of course—one that he would do well to sort out before attracting a crowd.)

If you have been avoiding public speaking, I hope you find the following points helpful:

1. Admit that you have a problem

No one is likely to drag you in front of a crowd and force you to produce audible sentences. Thus, you can probably avoid speaking in public for the rest of your life. Even if you are one day put on trial for murder, you can refuse to testify in your own defense. If your mother dies and your father asks that you say a few words at the funeral, you can always retreat into your grief. Bill Clinton didn't speak at his mother's funeral, and he is famously at ease in front of a crowd. Everyone already knows that you loved your mother. So, yes, you can probably keep silent until you get safely into a grave of your own.

But the fear will periodically make you miserable, and it will limit your opportunities in life. Thomas Jefferson aside, the people who currently run the world were first willing to run a meeting, deliver a speech, or debate opponents in a public forum. You might feel that you haven't paid much of a price for avoiding the crowd, but you don't know what your life would be like if you had become a competent public speaker. If you are in college, or just beginning your career, or even somewhere near its middle, it is time to overcome your fear.

2. Get some tools

You can do many things to improve your ability to speak in public: You can read books on shyness, anxiety, the art of giving presentations, and other relevant topics. You can take classes in public speaking, acting, or improv, or join a group like Toastmasters. You can discuss your fears with a psychologist or a psychiatrist, and ask the latter to prescribe medications—beta-blockers, for instance—that might reduce your stage fright.[] I especially recommend that you learn to meditate. Like getting enough food, sleep, and exercise, meditation helps with almost anything in life. And the feeling of self-consciousness can be directly undermined through meditation.

I wouldn't discourage you from experimenting with all of these things—but let me discourage you from doing any of them in lieu of taking the next opportunity that arises for you to speak. You cannot afford to live your life as if it were a dress rehearsal for some future life. By all means, do whatever seems likely to make you more comfortable in front of a crowd, but not as a way of delaying the next step.

3. Agree to speak when the opportunity arises

As has been said of many other problems in life, the only way out is through. You must now accomplish a belated forward escape through the birth canal of your own mind. It is time to actually arrive where you currently stand. Yes, you can convince yourself that you're not ready, or that the next opportunity to speak is best declined for reasons that have nothing to do with your fear. That might be true. I am not suggesting that you should agree to take the roll for your local branch of the Ku Klux Klan. But when given the chance, you should address any sane audience that will listen to you. By all means start small, and don't wait for a formal invitation: If your friends are giving toasts over dinner, offer one as well. If you attend a lecture, stand up and pose a question at the end. If you're asked to deliver a presentation in school or at work, agree without hesitating. Are there any volunteers to lead next week's journal club? From now on, your answer is "Yes."

4. Accept your anxiety

No matter how nervous you feel while speaking in public, you are likely to have an exaggerated sense of how nervous you appear—and this will tend to make your anxiety worse. Watching yourself speak on video can reverse this vicious circle: because discovering that your nerves are not as visible as you fear can lead you to feel increasingly comfortable on stage.

You can also strip the symptoms of anxiety of their psychological content—by experiencing them as purely physical sensations, like a pain in the knee. In fact, the feeling of anxiety is nearly identical to excitement or some other state of arousal that is not intrinsically negative. You can choose to feel it as a mere influx of energy and even use it as such. This is liberating—and your freedom does not depend on getting rid of these sensations.

5. Prepare something to say

I have been in every state of readiness when speaking to large crowds, ranging from having prepared nothing in advance to having committed every word of my lecture to memory. In my opinion, neither of these extremes is ideal. But you should definitely err on the side of preparation. If an event is worth doing, it is usually worth preparing for.

Some people avoid writing and rehearsing a talk as a way of avoiding their fear. But taking the stage in the hope of giving a brilliant extemporaneous performance is generally a mistake. Granted, for those who know their subject deeply and naturally speak well, this approach offers a feeling of freedom—but at the expense of structure and content. When I speak off the cuff, I often fail to cover important points.

Most speakers have learned that PowerPoint should be restricted to interesting images and other graphical aids, with a minimum of text. A few seasoned academics are holding out, however, and still oppress their audiences with walls of words, often in random fonts and terrible colors, so that they can turn their backs at regular intervals and consult a full set of notes. Do not do this.

A decision to use slides has other implications. Some topics require visual data, of course, and the question becomes not whether to use slides, but how many. However, slides always divert some of the audience's attention away from the speaker. If you are afraid of your audience, this has an obvious benefit—but it also comes at a price. Imagine Martin Luther King, Jr., using PowerPoint, and the price will be clear: To truly connect with an audience, you want their attention on you. To change slides every thirty seconds is to be rendered nearly invisible by the apparatus. Having too many images can also force you to race to the end of your talk. A final flurry of slides and apologies depresses everyone.

6. Prepare to say it

Although too much preparation can pose problems of its own, if a talk seems especially important, I sometimes memorize it. For instance, when I spoke at TED, where time limits are enforced down to the second, I knew in advance every sentence I would utter. There is a power in this, of course—it allows you to say exactly what you intend—but it forces you to spend most of your mental energy remembering the script that you have written. This is not the same as thinking out loud on stage, and the difference sometimes shows. When walking such a mnemonic tightrope, any digression, no matter how clever or important, can lead some fatal distance from your text. Without notes, you may never regain your footing.

Another problem with a performance that relies entirely on memory is that it becomes just that: a performance. I tend to be uncomfortable with this aspect of public speaking. I cannot shake the feeling that there is something dishonest about knowing exactly what one is going to say to an audience. Of course, it is still possible to "own" memorized lines upon delivery. At TED, for instance, I almost burst into tears when describing the practice of "honor killing." I knew that I was going to talk about fathers who murder their daughters for the crime of being raped, and I knew exactly what I was going to say about them. But I hadn't known that my own daughter would take her first steps the morning of my lecture. When delivering my lines exactly as I had rehearsed, I suddenly awoke to the reality of what I was talking about.

The middle realm of preparation entails having some notes, or even the entire text of your lecture safely on a lectern in front of you. The option of wandering the stage with sheets of paper fluttering in your hand should be declined. What appears to be a thoughtful silence at the lectern can seem like free fall to terminal velocity when one is shuffling pages in full view of the audience. If you want to roam the stage, you need to memorize the structure of your talk, or remember enough of it to be cued by your slides. And while you generally needn't memorize your talk verbatim, it's good to know how you will begin and how you will end.

The shorter your talk, the more you can rehearse it. But even an hour-long lecture can be rehearsed many times before you finally deliver it. In fact, rehearsing a talk is part of writing it, because one inevitably finds new things to say in the process. One also discovers that certain words or phrases that read well on the page are awkward to actually speak.

It is also extremely helpful to find someone you trust to give you feedback. This can be intimidating at first, because it requires speaking formally in front of one person, and perhaps not doing such a good job of it. Rather than attempt to deliver your lecture while looking intently into this person's startled eyes, look into the depths of an imaginary crowd. If this feels odd in the presence of your friend, turn your back and pretend the audience is in the other direction. Do whatever you need to do to accomplish your goal—which is to speak the way you intend to speak at the event itself. Talking as if to only one person is not a good way of doing this.

I am aware that by recommending the aid of a critic, I'm asking you to surmount a large portion of your fear at the outset. In fact, many novice speakers worry most about the presence of friends and loved ones at public events. If your anxiety is made worse by the thought that people you know will be at your event—and it is not a wedding or some other social function—by all means banish them. It is, nevertheless, a very good idea to find one person you can practice your talk with in advance.

And make this practice as realistic as possible. Allow yourself a few false starts, perhaps, but thereafter pretend that you are at the event itself: If you make a mistake, you cannot just quit and start over. Once you have gone through your talk a few times, and your friend has heard the worst you can deliver, an important transformation will have occurred: You will be impervious to embarrassment. Provided you can trust this person's judgment regarding tone and content, he or she will be an indispensable resource for you when preparing talks in the future.

7. Say it

If you've done your work beforehand, the event itself should hold few surprises. Needless to say, it is much better to arrive at the venue early, and pass the time in the green room or at a nearby coffee shop, than to be late and flustered. I recommend that once you finally take the stage, you speak to your audience as if you were having a real conversation—not like Pericles singing the praises of the Athenian dead. Admittedly, this opinion makes a virtue of necessity, because I am no Pericles. Speaking in a tone and cadence appropriate to a normal conversation will never produce great oratory: You will not sound like Martin Luther King, Jr. (or Hitler). For this reason, you are unlikely to elicit shouts of jubilation from your audience or inspire a riot. And while an informal mode of speech may be good in a hall, it often lacks some of the energy that people expect on television. Long pauses, for instance, can be effective in person but boring on video. Nevertheless, speaking naturally allows one to stand free of all pretense.

In any case, you will probably feel less like MLK when you appear on stage than like yourself under pressure. Many novice speakers apologize to their audience for being nervous. I recommend that you not do this. It takes the audience's attention away from whatever it is they came to hear you say—and the less time the audience spends worrying about you, the better. As I've said, people rarely appear as nervous as they feel. I once witnessed a speaker produce what seemed like a gallon of sweat over the course of a scientific presentation. At the end of the hour, he looked like had been sprayed with a hose. But I can remember marveling at the fact that he didn't seem nervous. I suppose he must have been terrified, but his talk was entirely lucid and quite interesting. I left the hall wondering whether he had some problem regulating his body temperature. Had he announced that he was nervous at the outset, however, the subsequent hour of waterworks would have been harrowing to behold.

Finally, it is worth remembering that most audiences are extremely supportive. With some obvious exceptions, the people you are speaking to want to understand what you have come to say. They want you to give a good talk. They are not waiting for you to fail. Recall why you took the stage in the first place: You have something that you believe is worth communicating. What might have once seemed like a high wire act is, in the end, quite simple: You are merely having a conversation with your fellow human beings.

Several readers have wondered why I neglected to mention cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in this context, as it is the current gold standard for the treatment of social anxiety and stage fright. No doubt I should have. It is also worth pointing out that drugs like beta-blockers are discouraged in CBT, because their use constitutes a way of avoiding, rather than accepting and transcending, the experience of anxiety. I agree that beta-blockers are generally not a good long-term solution to the problem of stage fright. (9/15/11)↩

Lying

As it was in Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, and Othello, so it is in life. Most forms of private vice and public evil are kindled and sustained by lies. Acts of adultery and other personal betrayals, financial fraud, government corruption—even murder and genocide—generally require an additional moral defect: a willingness to lie.

In Lying, bestselling author and neuroscientist Sam Harris argues that we can radically simplify our lives and improve society by merely telling the truth in situations where others often lie. He focuses on "white" lies—those lies we tell for the purpose of sparing people discomfort—for these are the lies that most often tempt us. And they tend to be the only lies that good people tell while imagining that they are being good in the process.

This essay is quite brilliant. (I was hoping it would be, so I wouldn't have to lie.) I honestly loved it from beginning to end. LYING is the most thought-provoking read of the year.

Ricky Gervais

Humans have evolved to lie well, and no doubt you've seen the social lubrication at work. In many cases, we might not think of it as a true "lie": perhaps a "white lie" once in a blue moon, the omission of a sensitive detail here and there, false encouragement of others when we see no benefit in dashing someone's hopes, and the list goes on. In LYING, Sam Harris demonstrates how to benefit from being brutally—but pragmatically—honest. It's a compelling little book with a big impact.

Tim Ferriss, angel investor and author of the #1 New York Times bestsellers, The 4-Hour Body and The 4-Hour Workweek

In this brief but illuminating work, Sam Harris applies his characteristically calm and sensible logic to a subject that affects us all—the human capacity to lie. And by the book's end, Harris compels you to lead a better life because the benefits of telling the truth far outweigh the cost of lies—to yourself, to others, and to society.

Neil deGrasse Tyson, Astrophysicist, American Museum of Natural History

LYING has been published in two electronic formats: as a Kindle Single and as a PDF. If you don't have a Kindle, you can read the Kindle version using the Kindle Reader App on your iPad, iPhone, Blackberry, PC, or other device. The PDF edition has been beautifully designed by Hop Studios and can be forwarded to others.

Four ways 9/11 changed America's attitude toward religion

September 9, 2011

Articles of Faith: The Importance of Understanding Religion in a Post-9/11 World

By Amy Sullivan

Some thought leaders and policymakers embraced Samuel Huntington's idea that the West was engaged in a "clash of civilizations" with Islam. Meanwhile, neo-atheists led by Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens put forward their own theory of a world split between civilized secularists and dangerous religionists.

September 11, 2011

(Photo by Sprengben)

Yesterday my daughter asked, "Where does gravity come from?" She is two and a half years old. I could say many things on this subject—most of which she could not possibly understand—but the deep and honest answer is "I don't know."

What if I had said, "Gravity comes from God"? That would be merely to stifle her intelligence—and to teach her to stifle it. What if I told her, "Gravity is God's way of dragging people to hell, where they burn in fire. And you will burn there forever if you doubt that God exists"? No Christian or Muslim can offer a compelling reason why I shouldn't say such a thing—or something morally equivalent—and yet this would be nothing less than the emotional and intellectual abuse of a child. In fact, I have heard from thousands of people who were oppressed this way, from the moment they could speak, by the terrifying ignorance and fanaticism of their parents.

Ten years have now passed since many of us first felt the jolt of history—when the second plane crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center. We knew from that moment that things can go terribly wrong in our world—not because life is unfair, or moral progress impossible, but because we have failed, generation after generation, to abolish the delusions of our ignorant ancestors. The worst of these ideas continue to thrive—and are still imparted, in their purest form, to children.

What is the meaning of life? What is our purpose on earth? These are some of the great, false questions of religion. We need not answer them—for they are badly posed—but we can live our answers all the same. At a minimum, we must create the conditions for human flourishing in this life—the only life of which we can be certain. That means we should not terrify our children with thoughts of hell, or poison them with hatred for infidels. We should not teach our sons to consider women their future property, or convince our daughters that they are property even now. And we must decline to tell our children that human history began with magic and will end with bloody magic—perhaps soon, in a glorious war between the righteous and the rest. One must be religious to fail the young so abysmally—to derange them with fear, bigotry, and superstition even as their minds are forming—and one cannot be a serious Christian, Muslim, or Jew without doing so in some measure.

Such sins against reason and compassion do not represent the totality of religion, of course—but they lie at its core. As for the rest—charity, community, ritual, and the contemplative life—we need not take anything on faith to embrace these goods. And it is one of the most damaging canards of religion to insist that we must.

People of faith recoil from observations like these. They reflexively point to all the good that has been done in the name of God and to the millions of devout men and women, even within conservative Muslim societies, who do no harm to anyone. And they insist that people at every point on the spectrum of belief and unbelief commit atrocities from time to time. This is all true, of course, and truly irrelevant. The groves of faith are now ringed by a forest of non sequiturs.

Whatever else may be wrong with our world, it remains a fact that some of the most terrifying instances of human conflict and stupidity would be unthinkable without religion. And the other ideologies that inspire people to behave like monsters—Stalinism, fascism, etc.—are dangerous precisely because they so resemble religions. Sacrifice for the Dear Leader, however secular, is an act of cultic conformity and worship. Whenever human obsession is channeled in these ways, we can see the ancient framework upon which every religion was built. In our ignorance, fear, and craving for order, we created the gods. And ignorance, fear, and craving keep them with us.

What defenders of religion cannot say is that anyone has ever gone berserk, or that a society ever failed, because people became too reasonable, intellectually honest, or unwilling to be duped by the dogmatism of their neighbors. This skeptical attitude, born of equal parts care and curiosity, is all that "atheists" recommend—and it is typical of nearly every intellectual pursuit apart from theology. Only on the subject of God can smart people still imagine that they reap the fruits of human intelligence even as they plow them under.

Ten years have passed since a group of mostly educated and middle-class men decided to obliterate themselves, along with three thousand innocents, to gain entrance to an imaginary Paradise. This problem was always deeper than the threat of terrorism—and our waging an interminable "war on terror" is no answer to it. Yes, we must destroy al Qaeda. But humanity has a larger project—to become sane. If September 11, 2001, should have taught us anything, it is that we must find honest consolation in our capacity for love, creativity, and understanding. This remains possible. It is also necessary. And the alternatives are bleak.

September 3, 2011

Ask Sam Harris Anything #2

The full video is an hour long. Links to specific topics/questions are provided below:

1. Eternity and the meaning of life 0:42

2. Do we have free will? 4:43

3. How can we convince religious people to abandon their beliefs? 14:52

4. How can atheists live among the faithful? 19:09

5. How should we talk to children about death? 21:52

6. Does human life have intrinsic value? 26:01

7. Why should we be confident in the authority of science? 30:36

8. How can one criticize Islam after the terrorism in Norway? 35:43

9. Should atheists join with Christians against Islam? 41:50

10. What does it mean to speak about the human mind objectively? 45:17

11. How can spiritual claims be scientifically justified? 50:14

12. Why can't religion remain a private matter? 54:52

13. What do you like to speak about at public events? 58:09

Ask Sam Harris Anything #1

In which I respond to questions and comments posted on Reddit.

September 2, 2011

Inside the List: Reading September 11th

An article last month in The Christian Century explored the role of 9/11 in giving birth to so-called New Atheists like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, who got things going with "The End of Faith" (2004), which spent 33 weeks on the paperback list.

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9007 followers