Sam Harris's Blog, page 33

July 23, 2011

The Invisible Big Kahuna

By Andrew Zak Williams

Andrew Zak Williams discusses this week's New Statesman article in which prominent atheists told him their reasons for non-belief.

July 18, 2011

Calling (Out) David Eagleman

The above talk was sent to me by a reader and is well worth watching. In it, the neuroscientist David Eagleman says many very reasonable things and says them well. Unfortunately, on the subject of religion he appears to make a conscious effort to play the good cop to the bad cop of "the new atheism." This posture will win him many friends, but it is intellectually dishonest. When one reads between the lines—or even when one just reads the lines—it becomes clear that what Eagleman is saying is every bit as deflationary as anything Dawkins, Dennett, Hitchens or I say about the cherished doctrines of the faithful.

I don't know Eagleman, but I've invited him to discuss these and other issues with me on this blog. He also has a book out on the brain that looks very interesting and which I intend to read:

Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain

July 5, 2011

Drugs and the Meaning of Life

Everything we do is for the purpose of altering consciousness. We form friendships so that we can feel certain emotions, like love, and avoid others, like loneliness. We eat specific foods to enjoy their fleeting presence on our tongues. We read for the pleasure of thinking another person's thoughts. Every waking moment—and even in our dreams—we struggle to direct the flow of sensation, emotion, and cognition toward states of consciousness that we value.

Drugs are another means toward this end. Some are illegal; some are stigmatized; some are dangerous—though, perversely, these sets only partially intersect. There are drugs of extraordinary power and utility, like psilocybin (the active compound in "magic mushrooms") and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which pose no apparent risk of addiction and are physically well-tolerated, and yet one can still be sent to prison for their use—while drugs like tobacco and alcohol, which have ruined countless lives, are enjoyed ad libitum in almost every society on earth. There are other points on this continuum—3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or "Ecstasy") has remarkable therapeutic potential, but it is also susceptible to abuse, and it appears to be neurotoxic.[]

One of the great responsibilities we have as a society is to educate ourselves, along with the next generation, about which substances are worth ingesting, and for what purpose, and which are not. The problem, however, is that we refer to all biologically active compounds by a single term—"drugs"—and this makes it nearly impossible to have an intelligent discussion about the psychological, medical, ethical, and legal issues surrounding their use. The poverty of our language has been only slightly eased by the introduction of terms like "psychedelics" to differentiate certain visionary compounds, which can produce extraordinary states of ecstasy and insight, from "narcotics" and other classic agents of stupefaction and abuse.

Drug abuse and addiction are real problems, of course—the remedy for which is education and medical treatment, not incarceration. In fact, the worst drugs of abuse in the United States now appear to be prescription painkillers, like oxycodone. Should these medicines be made illegal? Of course not. People need to be informed about them, and addicts need treatment. And all drugs—including alcohol, cigarettes, and aspirin—must be kept out of the hands of children.

I discuss issues of drug policy in some detail in my first book, The End of Faith (pp. 158-164), and my thinking on the subject has not changed. The "war on drugs" has been well lost, and should never have been waged. While it isn't explicitly protected by the U.S. Constitution, I can think of no political right more fundamental than the right to peacefully steward the contents of one's own consciousness. The fact that we pointlessly ruin the lives of nonviolent drug users by incarcerating them, at enormous expense, constitutes one of the great moral failures of our time. (And the fact that we make room for them in our prisons by paroling murderers and rapists makes one wonder whether civilization isn't simply doomed.)

I have a daughter who will one day take drugs. Of course, I will do everything in my power to see that she chooses her drugs wisely, but a life without drugs is neither foreseeable, nor, I think, desirable. Someday, I hope she enjoys a morning cup of tea or coffee as much as I do. If my daughter drinks alcohol as an adult, as she probably will, I will encourage her to do it safely. If she chooses to smoke marijuana, I will urge moderation.[] Tobacco should be shunned, of course, and I will do everything within the bounds of decent parenting to steer her away from it. Needless to say, if I knew my daughter would eventually develop a fondness for methamphetamine or crack cocaine, I might never sleep again. But if she does not try a psychedelic like psilocybin or LSD at least once in her adult life, I will worry that she may have missed one of the most important rites of passage a human being can experience.

This is not to say that everyone should take psychedelics. As I will make clear below, these drugs pose certain dangers. Undoubtedly, there are people who cannot afford to give the anchor of sanity even the slightest tug. It has been many years since I have taken psychedelics, in fact, and my abstinence is borne of a healthy respect for the risks involved. However, there was a period in my early 20's when I found drugs like psilocybin and LSD to be indispensable tools of insight, and some of the most important hours of my life were spent under their influence. I think it quite possible that I might never have discovered that there was an inner landscape of mind worth exploring without having first pressed this pharmacological advantage.

While human beings have ingested plant-based psychedelics for millennia, scientific research on these compounds did not begin until the 1950's. By 1965, a thousand studies had been published, primarily on psilocybin and LSD, many of which attested to the usefulness of psychedelics in the treatment of clinical depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), alcohol addiction, and the pain and anxiety associated with terminal cancer. Within a few years, however, this entire field of research was abolished in an effort to stem the spread of these drugs among the general public. After a hiatus that lasted an entire generation, scientific research on the pharmacology and therapeutic value of psychedelics has quietly resumed.

The psychedelics include chemicals like psilocybin, LSD, DMT, and mescaline—all of which powerfully alter cognition, perception, and mood. Most seem to exert their influence through the serotonin system in the brain, primarily by binding to 5-HT2A receptors (though several have affinity for other receptors as well), leading to increased neuronal activity in prefrontal cortex (PFC). While the PFC in turn modulates subcortical dopamine production, the effect of psychedelics appears to take place largely outside dopamine pathways (which might explain why these drugs are not habit forming).

The mere existence of psychedelics would seem to establish the material basis of mental and spiritual life beyond any doubt—for the introduction of these substances into the brain is the obvious cause of any numinous apocalypse that follows. It is possible, however, if not actually plausible, to seize this datum from the other end and argue, and Aldous Huxley did in his classic essay, The Doors of Perception, that the primary function of the brain could be eliminative: its purpose could be to prevent some vast, transpersonal dimension of mind from flooding consciousness, thereby allowing apes like ourselves to make their way in the world without being dazzled at every step by visionary phenomena irrelevant to their survival. Huxley thought that if the brain were a kind of "reducing valve" for "Mind at Large," this would explain the efficacy of psychedelics: They could simply be a material means of opening the tap.

Unfortunately, Huxley was operating under the erroneous assumption that psychedelics decrease brain activity. However, modern techniques of neuroimaging have shown that these drugs tend to increase activity in many regions of the cortex (and in subcortical structures as well). Still, the action of these drugs does not rule out dualism, or the existence of realms of mind beyond the brain—but then nothing does. This is one of the problems with views of this kind: They appear to be unfalsifiable.[]

Of course, the brain does filter an extraordinary amount of information from consciousness. And, like many who have taken these drugs, I can attest that psychedelics certainly throw open the gates. Needless to say, positing the existence of a "Mind at Large" is more tempting in some states of consciousness than in others. And the question of which view of reality we should privilege is, at times, worth considering. But these drugs can also produce mental states that are best viewed in clinical terms as forms of psychosis. As a general matter, I believe we should be very slow to make conclusions about the nature of the cosmos based upon inner experience — no matter how profound these experiences seem.

However, there is no question that the mind is vaster and more fluid than our ordinary, waking consciousness suggests. Consequently, it is impossible to communicate the profundity (or seeming profundity) of psychedelic states to those who have never had such experiences themselves. It is, in fact, difficult to remind oneself of the power of these states once they have passed.

Many people wonder about the difference between meditation (and other contemplative practices) and psychedelics. Are these drugs a form of cheating, or are they the one, indispensable vehicle for authentic awakening? They are neither. Many people don't realize that all psychoactive drugs modulate the existing neurochemistry of the brain—either by mimicking specific neurotransmitters or by causing the neurotransmitters themselves to be more active. There is nothing that one can experience on a drug that is not, at some level, an expression of the brain's potential. Hence, whatever one has experienced after ingesting a drug like LSD is likely to have been experienced, by someone, somewhere, without it.

However, it cannot be denied that psychedelics are a uniquely potent means of altering consciousness. If a person learns to meditate, pray, chant, do yoga, etc., there is no guarantee that anything will happen. Depending on his aptitude, interest, etc., boredom could be the only reward for his efforts. If, however, a person ingests 100 micrograms of LSD, what will happen next will depend on a variety of factors, but there is absolutely no question that something will happen. And boredom is simply not in the cards. Within the hour, the significance of his existence will bear down upon our hero like an avalanche. As Terence McKenna[] never tired of pointing out, this guarantee of profound effect, for better or worse, is what separates psychedelics from every other method of spiritual inquiry. It is, however, a difference that brings with it certain liabilities.

Ingesting a powerful dose of a psychedelic drug is like strapping oneself to a rocket without a guidance system. One might wind up somewhere worth going—and, depending on the compound and one's "set and setting," certain trajectories are more likely than others. But however methodically one prepares for the voyage, one can still be hurled into states of mind so painful and confusing as to be indistinguishable from psychosis. Hence, the terms "psychotomimetic" and "psychotogenic" that are occasionally applied to these drugs.

I have visited both extremes on the psychedelic continuum. The positive experiences were more sublime than I could have ever imagined or than I can now faithfully recall. These chemicals disclose layers of beauty that art is powerless to capture and for which the beauty of Nature herself is a mere simulacrum. It is one thing to be awestruck by the sight of a giant redwood and to be amazed at the details of its history and underlying biology. It is quite another to spend an apparent eternity in egoless communion with it. Positive psychedelic experiences often reveal how wondrously at ease in the universe a human being can be—and for most of us, normal waking consciousness does not offer so much as a glimmer of these deeper possibilities.

People generally come away from such experiences with a sense that our conventional states of consciousness obscure and truncate insights and emotions that are sacred. If the patriarchs and matriarchs of the world's religions experienced such states of mind, many of their claims about the nature of reality can make subjective sense. The beautific vision does not tell you anything about the birth of the cosmos—but it does reveal how utterly transfigured a mind can be by a full collision with the present moment.

But as the peaks are high, the valleys are deep. My "bad trips" were, without question, the most harrowing hours I have ever suffered—and they make the notion of hell, as a metaphor if not a destination, seem perfectly apt. If nothing else, these excruciating experiences can become a source of compassion. I think it would be impossible to have any sense of what it is like to suffer from mental illness without having briefly touched its shores.

At both ends of the continuum time dilates in ways that cannot be described—apart from saying that these experiences can seem eternal. I have had sessions, both positive and negative, in which any knowledge that I had ingested a drug had been extinguished, and all memories of my past along with it. Full immersion in the present moment, to this degree, is synonymous with the feeling that one has always been, and will always be, in precisely this condition. Depending on the character of one's experience at that point, notions of salvation and damnation do not seem hyperbolic. In my experience, Blake's line about beholding "eternity in an hour" neither promises, nor threatens, too much.

In the beginning, my experiences with psilocybin and LSD were so positive that I could not believe a bad trip was possible. Notions of "set and setting," admittedly vague, seemed sufficient to account for this. My mental set was exactly as it needed to be—I was a spiritually serious investigator of my own mind—and my setting was generally one of either natural beauty or secure solitude.

I cannot account for why my adventures with psychedelics were uniformly pleasant until they weren't—but when the doors to hell finally opened, they appear to have been left permanently ajar. Thereafter, whether or not a trip was good in the aggregate, it generally entailed some harrowing detour on the path to sublimity. Have you ever traveled, beyond all mere metaphors, to the Mountain of Shame and stayed for a thousand years? I do not recommend it.

(Pokhara, Nepal)

On my first trip to Nepal, I took a rowboat out on Phewa Lake in Pokhara, which offers a stunning view of the Annapurna range. It was early morning, and I was alone. As the sun rose over the water, I ingested 400 micrograms of LSD. I was 20 years old and had taken the drug at least ten times previously. What could go wrong?

Everything, as it turns out. Well, not everything—I didn't drown. And I have a vague memory of drifting ashore and of being surrounded by a group of Nepali soldiers. After watching me for a while, as I ogled them over the gunwale like a lunatic, they seemed on the verge of deciding what to do with me. Some polite words of Esperanto, and a few, mad oar strokes, and I was off shore and into oblivion. So I suppose that could have ended differently.

But soon there was no lake or mountains or boat—and if I had fallen into the water I am pretty sure there would have been no one to swim. For the next several hours my mind became the perfect instrument of self-torture. All that remained was a continuous shattering and terror for which I have no words.

These encounters take something out of you. Even if drugs like LSD are biologically safe, the potential for extremely unpleasant and destabilizing experiences presents its own risks. I believe I was positively affected for weeks and months by my good trips, and negatively affected by the bad ones. Given these roulette-like odds, one can only recommend these experiences with caution.

While meditation can open the mind to a similar range of conscious states, they are reached far less haphazardly. If LSD is like being strapped to rocket, learning to meditate is like gently raising a sail. Yes, it is possible, even with guidance, to wind up someplace terrifying—and there are people who probably shouldn't spend long periods in intensive practice. But the general effect of meditation training is of settling ever more fully into one's own skin, and suffering less, rather than more there.

As I discussed in The End of Faith, I view most psychedelic experiences as potentially misleading. Psychedelics do not guarantee wisdom. They merely guarantee more content. And visionary experiences, considered in their totality, appear to me to be ethically neutral. Therefore, it seems that psychedelic ecstasy must be steered toward our personal and collective well-being by some other principle. As Daniel Pinchbeck pointed out in his highly entertaining book, Breaking Open the Head, the fact that both the Mayans and the Aztecs used psychedelics, while being enthusiastic practitioners of human sacrifice, makes any idealistic link between plant-based shamanism and an enlightened society seem terribly naive.

As I will discuss in future essays, the form of transcendence that appears to link directly to ethical behavior and human well-being is the transcendence of egoity in the midst of ordinary waking consciousness. It is by ceasing to cling to the contents of consciousness—to our thoughts, moods, desires, etc.—that we make progress. Such a project does not, in principle, require that we experience more contents.[] The freedom from self that is both the goal and foundation of "spiritual" life is coincident with normal perception and cognition—though, admittedly, this can be difficult to realize.

The power of psychedelics, however, is that they often reveal, in the span of a few hours, depths of awe and understanding that can otherwise elude us for a lifetime. As is often the case, William James said it about as well as words permit[] :

One conclusion was forced upon my mind at that time, and my impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded. How to regard them is the question,—for they are so discontinuous with ordinary consciousness. Yet they may determine attitudes though they cannot furnish formulas, and open a region though they fail to give a map. At any rate, they forbid a premature closing of our accounts with reality.

(The Varieties of Religious Experience, p. 388)

NOTES:

What is moderation? Let's just say that I've never met a person who smokes marijuana every day who I thought wouldn't benefit from smoking less (and I've never met someone who has never tried it who I thought wouldn't benefit from smoking more).↩

Physicalism, by contrast, could be easily falsified. If science ever established the existence of ghosts, or reincarnation, or any other phenomenon which would place the human mind (in whole or in part) outside the brain, physicalism would be dead. The fact that dualists can never say what would count as evidence against their views makes this ancient philosophical position very difficult to distinguish from religious faith.↩

Terence McKenna is one person I regret not getting to know. Unfortunately, he died from brain cancer in 2000, at the age of 53. His books are well worth reading, and I have recommended several below, but he was, above all, an amazing speaker. It is true that his eloquence often led him to adopt positions which can only be described (charitably) as "wacky," but the man was undeniably brilliant and always worth listening to. ↩

I should say, however, that there are psychedelic experiences that I have not had, which appear to deliver a different message. Rather than being states in which the boundaries of the self are dissolved, some people have experiences in which the self (in some form) appears to be transported elsewhere. This phenomenon is very common with the drug DMT, and it can lead its initiates to some very startling conclusions about the nature of reality. More than anyone else, Terence McKenna was influential in bringing the phenomenology of DMT into prominence.

DMT is unique among psychedelics for a several reasons. Everyone who has tried it seems to agree that it is the most potent hallucinogen available (not in terms of the quantity needed for an effective dose, but in terms of its effects). It is also, paradoxically, the shortest acting. While the effects of LSD can last ten hours, the DMT trance dawns in less than a minute and subsides in ten. One reason for such steep pharmacokinetics seems to be that this compound already exists inside the human brain, and it is readily metabolized by monoaminoxidase. DMT is in the same chemical class as psilocybin and the neurotransmitter serotonin (but, in addition to having an affinity for 5-HT2A receptors, it has been shown to bind to the sigma-1 receptor and modulate Na+ channels). Its function in the human body remains mysterious. Among the many mysteries and insults presented by DMT, it offers a final mockery of our drug laws: Not only have we criminalized naturally occurring substances, like cannabis; we have criminalized one of our own neurotransmitters.

Many users of DMT report being thrust under its influence into an adjacent reality where they are met by alien beings who appear intent upon sharing information and demonstrating the use of inscrutable technologies. The convergence of hundreds of such reports, many from first-time users of the drug who have not been told what to expect, is certainly interesting. It is also worth noting these accounts are almost entirely free of religious imagery. One appears far more likely to meet extraterrestrials or elves on DMT than traditional saints or angels. As I have not tried DMT, and have not had an experience of the sort that its users describe, I don't know what to make of any of this. ↩

Of course, James was reporting his experiences with nitrous oxide, which is an anesthetic. Other anesthetics, like ketamine hydrochloride and phencyclidine hydrochloride (PCP), have similar effects on mood and cognition at low doses. However, there are many differences between these drugs and classic psychedelics—one being that high doses of the latter do not lead to general anesthesia. ↩

Recommended Reading:

Huxley, A. The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell .

.

McKenna, T. True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author's Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil's Paradise .

.

Pinchbeck, D. Breaking Open the Head: A Psychedelic Journey into the Heart of Contemporary Shamanism .

.

Stevens, J. Storming Heaven: LSD and the American Dream .

.

Ratsch, C. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications .

.

Ott, J. Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, Their Plant Sources and History .

.

Strassman, R. DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor's Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences .

.

July 1, 2011

What's the Point of Transcendence?

My friend Jerry Coyne has posted a response to my recent video Q&A where he raises a few points in need of clarification about meditation, transcendence, spiritual experience, etc.:

This discussion continues at 21:25, when Sam criticizes atheists, scientists and secularists for failing to "connect to the character of those experiences" and for failing to "give some alternate explanation for them that is not entirely deflationary and demeaning and gives some warrant to the legitimacy of those experiences." He implies that these experiences are somehow beyond the purview of science. I find that strange given Sam's repeated emphasis on the value of science in studying mental states.

I'm not quite sure what he's getting at here, and he doesn't elaborate, but I don't see why giving credence to these über-transcendent experiences as experiences says anything about a reality behind them. Yes, they might indeed change one's personality and view of the world, but do any of us deny that?

I had similar experiences on various psychoactive substances when I was in college, and some of them were even transformative. The problem is not with us realizing that people can feel at one with the universe or, especially, at one with God; the problem comes with us taking this as evidence for some supernatural reality. What does it mean to say that an experience is legitimate? If someone thinks that he saw Jesus, I am prepared to believe that he thought that he saw Jesus, but I am not prepared to say that he really did see Jesus, nor that that constitutes any evidence for the existence of Jesus.

So my question for Sam would be this: "So if we accept that people do have these seriously transcendent experiences, what follows from that—beyond our simple desire to study the neurobiology behind them?"

These are all good points. I certainly didn't mean to suggest that transcendent experiences are "beyond the purview of science." On the contrary, I think they should be studied scientifically. And I don't believe that these experiences tell us anything about the cosmos (I called Deepak Chopra a "charlatan" for making unfounded claims of this sort). Nor do they tell us anything about history, or about the veracity of scripture. However, these experiences do have a lot to say about the nature of the human mind—not about its neurobiology, per se, but about its qualitative character (both actual and potential).

So, to answer Jerry's question: yes, many things follow from these transcendent experiences. Here's a short list:

It is possible to feel much better (in every sense of "better") than one tends to feel.

It is, in fact, possible to be utterly at ease in the world—and such ease is synonymous with relaxing, or fully transcending, the apparent boundaries of the "self." Those who have never experienced such peace of mind will view the preceding sentences as yet another eruption of "mumbo jumbo" on my part. And yet it is phenomenologically true to say that such states of well-being are there to be discovered. I am not claiming to have experienced all relevant states of this kind. But there are people who appear to have experienced none of them—and many of these people are atheists.

This is not surprising. After all, experiences of self-transcendence are generally only sought and interpreted in a religious or "spiritual" context—and these are precisely the phenomena that tend to increase a person's faith. How many Christians, having felt self-transcending love for their neighbors in church or body-dissolving bliss in prayer, decide to ditch Christianity? Not many, I would guess. How many people who never have experiences of this kind (no matter how hard they try) become atheists? I don't know, but there is no question that these states of mind act as a kind of filter: they get counted in support of ancient dogma by the faithful; and their absence seems to give my fellow atheists yet another reason to reject religion.

Reading the comments on Jerry's blog exposes the problem in full. There are several people there who have absolutely no idea what I'm talking about—and they take this to mean that I am not making sense. Of course, religious people often present the opposite problem: they tend to think they know exactly what I'm talking about, in so far as it can seem to support one religious doctrine or another. Both these orientations present impressive obstacles to understanding.

There is a connection between feeling transcendently good and being good.

Not all good feelings have an ethical valence, of course. And there are surely pathological forms of ecstasy. I have no doubt, for instance, that many suicide bombers feel extraordinarily good just before detonating themselves in a crowd. But there are forms of mental pleasure that seem intrinsically ethical. There are states of consciousness for which phrases like "boundless love and compassion" do not seem overblown. Of course, it is possible for a person to be unaware that this is a potential of the human mind or to imagine that such experiences must be signs of psychopathology. Again, such people tend to be atheists. And it is decidedly inconvenient for the forces of Reason that if a person wakes up tomorrow feeling "boundless love and compassion," the only people likely to acknowledge the legitimacy of his experience will be representatives of one or another religion (or New Age cult).

Certain patterns of thought and attention prevent us from accessing deeper (and wiser) states of well-being. Transcendent experiences, in so far as they are usually temporary, are often surrounded by a penumbra of other states and insights. Just as one can glimpse deeper strata of well-being, and briefly see the world by their logic, one can notice the impediments to feeling this way in each subsequent moment. There is no question that all of these mental states have neurophysiological correlates—but the neurophysiology often has subjective correlates. Understanding the first-person side of the equation is essential for understanding the phenomenon. Everything worth knowing about the human mind, good and bad, is taking place inside the brain. But that doesn't mean that there is nothing to know about the qualitative character of these events. Yes, qualitative character can be misleading, and certain ways of talking about it can manufacture fresh misunderstandings about the mind. But this doesn't mean that we can stop talking about the nature of conscious experience. At one level, there is nothing else to talk about.

Certain "spiritual" experiences can help us understand science. There are insights that one can have through meditation (that is, very close observation of first-person data) that line up rather well with what we know must be true at the level of the brain. I'll mention just two, which I have written about before and will return to in subsequent posts: (1) the ego/self is a construct and a cognitive illusion; (2) there is no such thing as free will. There is simply no question that these statements are well grounded scientifically (in fact, it is very difficult to even imagine a physical account of the human mind that would suggest their falsity at this point). So, here are two facts which science gives us good reason to believe, and which I believe we can know through introspection, but which seem quite paradoxical and troubling to most people.

As for the "various psychoactive substances" Jerry mentions, I'll address the risks and rewards of these in my next post.

June 29, 2011

Ask Sam Harris Anything #1

Wherein I respond to questions and comments posted on Reddit.

June 14, 2011

On Spiritual Truths

One day, you will find yourself outside this world which is like a mother's womb. You will leave this earth to enter, while you are yet in the body, a vast expanse, and know that the words, "God's earth is vast," name this region from which the saints have come.

—Jalal-ud-Din Rumi

Many of my fellow atheists consider all talk of "spirituality" or "mysticism" to be synonymous with mental illness, conscious fraud, or self-deception. I have argued elsewhere that this is a problem—because millions of people have had experiences for which "spiritual" and "mystical" seem the only terms available.

Of course, many of the beliefs people form on the basis of these experiences are false. But the fact that most atheists will view a statement like Rumi's, above, as a sign of the man's gullibility or derangement, places a kernel of truth amid the rantings of even our most gullible and deranged opponents.

Consider Sayed Qutb, Osama bin Laden's favorite philosopher. Qutb spent most of 1949 in Greeley, Colorado, and found, to his horror and satisfaction, that his American hosts were squandering their lives on gossip, trivial entertainments, and lawn maintenance. From this Dark Night of Suburbia, he concluded that western civilization was so spiritually barren that it must be destroyed.

As is often the case with religious conservatives, whatever ignorance and "death denial" didn't explain about Qutb, sexual frustration did:

The American girl is well acquainted with her body's seductive capacity. She knows it lies in the face, and in expressive eyes, and thirsty lips. She knows seductiveness lies in the round breasts, the full buttocks, and in the shapely thighs, sleek legs—and she shows all this and does not hide it.

(Sayyid Qutb, The America I Have Seen: In the Scale of Human Values, 1951)

These are not words of a man who has discerned the limits of romantic attachment. Being terrified of women, and yet as concupiscent as bonobo, Qutb is widely believed to have died a virgin. We can feel his pain. Needless to say, his puritanical attachment to Islam allowed him to make a virtue of necessity: What a relief it must have been to know that the Creator of the universe intended these terrifying creatures to live as slaves to men.

But Qutb was not wrong about everything. There is something degraded and degrading about many of our habits of attention. Perhaps I should just speak for myself on this point: It seems to me that I spend much of my waking life in a neurotic trance. My experiences in meditation suggest that there is an alternative to this, however. It is possible to stand free of the juggernaut of self, if only for a moment.

But the fact that human consciousness allows for remarkable experiences does not make the worldview of Sayed Qutb, or of Islam, or of revealed religion generally, any less divisive or ridiculous. The intellectual and moral stains of the world's religions—the misogyny, otherworldliness, narcissism, and illogic—are so ugly and indelible as to render all religious language suspect. And I share the concern, expressed by many atheists, that terms like "spiritual" and "mystical" are often used to make claims, not merely about the quality of certain experiences, but about the nature of the cosmos. The fact that one can lose one's sense of self in an ocean of tranquility does not mean that one's consciousness is immaterial or that it presided over the birth of the universe. This is the spurious linkage between contemplative experience and metaphysics that pseudo-scientists like Deepak Chopra find irresistible.

But, as I argue in The Moral Landscape, a maturing science of the mind should be able to help us understand and access the heights of human well-being. To do this, however, we must first acknowledge that these heights exist.

June 10, 2011

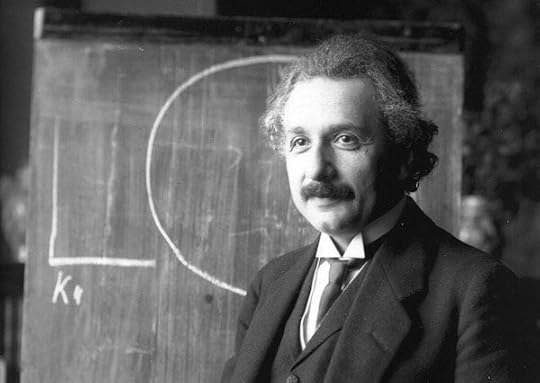

My Friend Einstein?

(Albert Einstein lecturing in Vienna in 1921)

In my last post, I suggested that Einstein shared my skepticism about free will. Nothing in my argument turned on this, of course: Several great physicists have believed in free will, and Einstein got many things wrong, both inside and outside of physics. One doesn't argue these points on the basis of authority in any case—and this is what distinguishes science and philosophy from religion. Respecting one's elders, however brilliant, is no substitute for making sense.

Nevertheless, it is generally interesting to know what great scientists believe. And a helpful reader has called my attention to the fact that Einstein viewed the connection between scientific and moral truth in terms similar to those I argue for in The Moral Landscape (thanks Matt!).

In the following essay, Einstein endorses a strong conception of moral truth, founded on axioms, and focused on the well-being of humanity. While he does not discuss progress in neuroscience and psychology—which, I maintain, makes the separation between ethics and science ultimately unsustainable—he seems to consider ethical truth to be on all fours with the truths of mathematics and the rest science.

I have added a few footnotes to clarify points of interest.

The Laws of Science and The Laws of Ethics

By Albert Einstein

Science searches for relations which are thought to exist independently of the searching individual. This includes the case where man himself is the subject. [1] Or the subject of scientific statements may be concepts created by ourselves, as in mathematics. Such concepts are not necessarily supposed to correspond to any objects in the outside world. However, all scientific statements and laws have one characteristic in common: they are "true or false" (adequate or inadequate). Roughly speaking, our reaction to them is "yes or "no."

The scientific way of thinking has a further characteristic. The concepts which it uses to build up its coherent systems are not expressing emotions. For the scientist, there is only "being," but no wishing, no valuing, no good, no evil; no goal. As long as we remain within the realm of science proper, we can never meet with a sentence of the type: "Thou shalt not lie." [2] There is something like a Puritan's restraint in the scientist who seeks truth: he keeps away from everything voluntaristic or emotional. Incidentally, this trait is the result of a slow development, peculiar to modern Western thought.

From this it might seem as if logical thinking were irrelevant for ethics. Scientific statements of facts and relations, indeed, cannot produce ethical directives. [3] However, ethical directives can be made rational and coherent by logical thinking and empirical knowledge. If we can agree on some fundamental ethical propositions, then other theoretical propositions can be derived from them, provided that the original premises are stated with sufficient precision. Such ethical premises play a similar role in ethics, to that played by axioms in mathematics.

This is why we do not feel at all that it is meaningless to ask such questions as: "Why should we not lie?" We feel that such questions are meaningful because in all discussions of this kind some ethical premises are tacitly taken for granted. We then feel satisfied when we succeed in tracing back the ethical directive in question to these basic premises. In the case of lying this might perhaps be done in some way such as this: Lying destroys confidence in the statements of other people. Without such confidence, social cooperation is made impossible or at least difficult. Such cooperation, however, is essential to make human life possible and tolerable. This means that the rule "Thou shalt not lie" has been traced back to the demands: "Human life shall be preserved" and "Pain and sorrow shall be lessened as much as possible."

But what is the origin of such ethical axioms? Are they arbitrary? Are they based on mere authority? Do they stem from experiences of men, and are they conditioned indirectly by such experiences?

For pure logic all axioms are arbitrary, including the axioms of ethics. But they are by no means arbitrary from a psychological and genetic point of view. They are derived from our inborn tendencies to avoid pain and annihilation, and from the accumulated emotional reaction of individuals to the behavior of their neighbors.

It is the privilege of man's moral genius, impersonated by inspired individuals, to advance ethical axioms which are so comprehensive and so well founded that men will accept them as grounded in the vast mass of their individual emotional experiences. Ethical axioms are found and tested not very differently from the axioms of science. Truth is what stands the test of experience.

(Out of My Later Years, pp. 114-115)

[1] Here, Einstein neatly distinguishes between epistemological and ontological "objectivity." Science is fully committed to the former; it is in no sense limited to the latter. There is no question that we can study human subjectivity—including the difference between misery and well-being—objectively.

[2] Einstein may seem to contradict the thesis I advance in The Moral Landscape here, but the rest of the text reveals that our views about moral truth are quite close. To my ear, the preceding sentences simply emphasize the epistemic objectivity of science and suggest that the notion of "moral duty" may be problematical (which, I believe, it is).

[3] Shades of Hume, no doubt, but keep reading…

June 7, 2011

You Do Not Choose What You Choose

(Photo by H.koppdelaney)

Many readers continue to find my position on free will bewildering. Most of the criticism I've received consists of some combination of the following claims:

Your account assumes that mental events are, at bottom, physical events. But if the mind is distinct from the brain (to any degree), this would allow for freedom of will.

You admit that mental events—like choices, efforts, intentions, reasoning, etc—cause certain of our actions. But such mental states presuppose free will for their very existence. Your position is self-contradictory: Either we are free to think and behave as we will, or there is no such thing as choice, effort, intention, reasoning, etc.

Even if my thoughts and actions are the product of unconscious causes, they are still my thoughts and actions. Anything that my brain does or chooses, whether consciously or not, is something that I have done or chosen. The fact that I cannot always be subjectively aware of the causes of my actions does not negate free will.

All of these objections express confusion about my basic premise. The first is simply false—my argument against free will does not require philosophical materialism. There is no question that (most) mental events are the product of physical events—but even if the human mind were part soul-stuff, nothing about my argument would change. The unconscious operations of a soul would grant you no more freedom than the unconscious physiology of your brain does.

If you don't know what your soul is going to do next, or why it behaved as it did a moment ago, you are not in control of your soul. This is obviously true in all cases where a person wishes he could feel or behave differently than he does: Think of the millions of good Christians whose souls happen to be gay, prone to obesity, and bored by prayer. The truth, however, is that free will is no more evident when a person does exactly what, in retrospect, he wishes he had done. The immaterial soul force that allows you to stay your diet is just as mysterious as the one that directs you to eat cherry pie for breakfast.

The second concern also misses the point: Yes, choices, efforts, intentions, reasoning, and other mental processes influence our behavior—but they are themselves part of a stream of causes which precede conscious awareness and over which we exert no ultimate control. My choices matter, but I cannot choose what I choose. And if it ever appears that I do—for instance, when going back and forth between two options—I do not choose to choose what I choose. There's a regress here that always ends in darkness. Subjectively, I must take a first step, or a last one, for reasons that are inscrutable to me.

Einstein (following Schopenhauer) once made the same point:

Honestly, I cannot understand what people mean when they talk about the freedom of the human will. I have a feeling, for instance, that I will something or other; but what relation this has with freedom I cannot understand at all. I feel that I will to light my pipe and I do it; but how can I connect this up with the idea of freedom? What is behind the act of willing to light the pipe? Another act of willing? Schopenhauer once said: Der Mensch kann was er will; er kann aber nicht wollen was er will (Man can do what he will but he cannot will what he wills). (Planck, M. Where is Science Going?, p. 201)

But many people believe that this problem of regress is a false one. For them, freedom of will is synonymous with the idea that, with respect to any specific thought or action, one could have thought or acted differently. But to say that I could have done otherwise is merely to think the thought, "I could have done otherwise" after doing whatever I, in fact, did. Rather than indicate my freedom, this thought is just an epitaph erected to moments past. What I will do next, and why, remains, at bottom, inscrutable to me. To declare my "freedom" is tantamount to saying, "I don't know why I did it, but it's the sort of thing I tend to do, and I don't mind doing it."

And this is why the last objection is just another way of not facing up to the problem. To say that "my brain" has decided to think or act in a particular way, whether consciously or not, and my freedom consists in this, is to ignore the very reason why people believe in free will in the first place: the feeling of conscious agency. People feel that they are the authors of their thoughts and actions, and this is the only reason why there seems to be a problem of free will worth talking about.

Each of us has many organs in addition to a brain that make unconscious "decisions"—but these are not events for which anyone feels responsible. Are you producing red blood cells and digestive enzymes at this moment? Your body is, of course, but if it "decided" not to do these things for some reason, you would be the victim of these changes, rather than their autonomous cause. To say that I am "responsible" for everything that goes on inside my skin because it's all "me," is to make a claim that bears no relationship to the feelings of agency and moral responsibility that make the idea of free will an enduring problem for philosophy.

As I have argued, however, the problem is not merely that free will makes no sense objectively (i.e. when our thoughts and actions are viewed from a third-person point of view); it makes no sense subjectively either. And it is quite possible to notice this, through introspection.

In fact, I will now perform an experiment in free will for all to see: I will write anything I want for the rest of this blog post. Whatever I write is, of course, something I have chosen to write. No one has compelled to do this. No one has assigned me a topic or demanded that I use certain words. I can be ungrammatical, if I pleased. And if I want to put a rabbit in this sentence, I am free to do it.

But paying attention to my stream of consciousness reveals that this notion of freedom does not reach very deep. Where did this "rabbit" come from? Why didn't I put an "elephant" in that sentence? I do not know. Was I free to do otherwise? This is a strange, and strangely vacuous, question. How can I say that I was free to do other than what I did, when the causes of what I did are invisible to me? Yes, even now I am free to change "rabbit" to "elephant," but if I were to do this, how could I explain it? It is impossible for me to know the cause of either choice. Either is compatible with my being compelled by the iron law of determinism, or buffeted by the winds of chance; but neither looks, or feels, like freedom. Rabbit or elephant? Or why not write something else entirely?

And what brings my deliberations on this matter to a close? This blog post must end sometime—and now I find that I want to get lunch. Am I free to resist this feeling? Well, yes, in the sense that no one is going to compel me at gunpoint to eat lunch this minute—but I'm hungry, and I want to eat it. Can I resist this feeling for a moment longer? Yes, of course—and for an indeterminate number of moments thereafter. But I am in no position to know why I make the effort in this instance but not in others. And why do my efforts cease precisely when they do? Now I feel that it is time for me to leave in any case. I'm hungry, yes, but it also seems like I've made my point. In fact, I can't think of anything else to say on the subject. And where is the freedom in that?

May 31, 2011

Free Will (And Why You Still Don't Have It)

(Photo by H.koppdelaney)

My last post on free will elicited a very heated response. Many readers sent emails questioning my sanity, and several asked to be permanently removed from my mailing list. Many others wrote to share the Good News that quantum mechanics has liberated the human mind from the prison of determinism. It seems I touched a nerve.

In the hopes of clearing up some confusion, I've culled another post from my discussion of free will in The Moral Landscape.

The human brain must respond to information coming from several domains: from the external world, from internal states of the body, and, increasingly, from a sphere of meaning—which includes spoken and written language, social cues, cultural norms, rituals of interaction, assumptions about the rationality of others, judgments of taste and style, etc. Generally, these streams of information seem unified in our experience:

You spot your best friend standing on the street corner looking strangely disheveled. You recognize that she is crying and frantically dialing her cell phone. Was she involved in a car accident? Did someone assault her? You rush to her side, feeling an acute desire to help. Your "self" seems to stand at the intersection of these lines of input and output. From this point of view, you tend to feel that you are the source of your own thoughts and actions. You decide what to do and not to do. You seem to be an agent acting of your own free will. The problem, however, is that this point of view cannot be reconciled with what we know about the human brain. All of our behavior can be traced to biological events about which we have no conscious knowledge: this has always suggested that free will is an illusion.

The physiologist Benjamin Libet famously demonstrated that activity in the brain's motor regions can be detected some 300 milliseconds before a person feels that he has decided to move. Another lab recently used fMRI data to show that some "conscious" decisions can be predicted up to 10 seconds before they enter awareness (long before the preparatory motor activity detected by Libet). Clearly, findings of this kind are difficult to reconcile with the sense that one is the conscious source of one's actions.

And the distinction between "higher" and "lower" systems in the brain offers no relief: for I no more initiate events in executive regions of my prefrontal cortex than I cause the creaturely outbursts of my limbic system. The truth seems inescapable: I, as the subject of my experience, cannot know what I will next think or do until a thought or intention arises; and thoughts and intentions are caused by physical events and mental stirrings of which I am not aware.

Of course, many scientists and philosophers realized long before the advent of experimental neuroscience that free will could not be squared with an understanding of the physical world. Nevertheless, many still deny this fact. For instance, the biologist Martin Heisenberg has observed that some fundamental processes in the brain, like the opening and closing of ion channels and the release of synaptic vesicles, occur at random, and cannot, therefore, be determined by environmental stimuli. Thus, much of our behavior can be considered "self-generated," and therein, he imagines, lies a basis for free will. But "self-generated" in this sense means only that these events originate in the brain. The same can be said for the brain states of a chicken.

If I were to learn that my decision to have a third cup of coffee this morning was due to a random release of neurotransmitters, how could the indeterminacy of the initiating event count as the free exercise of my will? Such indeterminacy, if it were generally effective throughout the brain, would obliterate any semblance of human agency. Imagine what your life would be like if all your actions, intentions, beliefs, and desires were "self-generated" in this way: you would scarcely seem to have a mind at all. You would live as one blown about by an internal wind. Actions, intentions, beliefs, and desires can only exist in a system that is significantly constrained by patterns of behavior and the laws of stimulus-response. In fact, the possibility of reasoning with other human beings—or, indeed, of finding their behaviors and utterances comprehensible at all—depends on the assumption that their thoughts and actions will obediently ride the rails of a shared reality. In the limit, Heisenberg's "self-generated" mental events would amount to utter madness.

And the indeterminacy specific to quantum mechanics offers no foothold. Even if our brains were quantum computers, the brains of chimps, dogs, and mice would be quantum computers as well. (I don't know of anyone who believes that these animals have free will.) And quantum effects are unlikely to be biologically salient in any case. They do drive evolution, as high-energy particles like cosmic rays cause point mutations in DNA, and the behavior of such particles passing through the nucleus of a cell is governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. (Evolution, therefore, seems unpredictable in principle.) But most neuroscientists do not view the brain as a quantum computer. Again, even if we knew that human consciousness depended upon quantum processes, it is pure hand-waving to suggest that quantum indeterminacy renders the concept of free will scientifically intelligible.

If the laws of nature do not strike most of us as incompatible with free will, it is because we have not imagined how human action would appear if all cause-and-effect relationships were understood. Consider the following thought experiment:

Imagine that a mad scientist has developed a means of controlling the human brain at a distance. What would it be like to watch him send a person to and fro on the wings of her "will"? Would there be even the slightest temptation to impute freedom to her? No. But this mad scientist is nothing more than causal determinism personified. What makes his existence so inimical to our notion of free will is that when we imagine him lurking behind a person's thoughts and actions—tweaking electrical potentials, manufacturing neurotransmitters, regulating genes, etc.—we cannot help but let our notions of freedom and responsibility travel up the puppet's strings to the hand that controls them.

To see that the addition of randomness—quantum mechanical or otherwise—does nothing to change this situation, we need only imagine the scientist basing the inputs to his machine on a shrewd arrangement of roulette wheels, or on the decay of some radioactive isotope. How would such unpredictable changes in the states of a person's brain constitute freedom?

All the relevant features of a person's inner life could be conserved—thoughts, moods, and intentions would still arise and beget actions—and yet, once we imagine a hypothetical mad scientist dispensing the appropriate cocktail of randomness and natural law, we are left with the undeniable fact that the conscious mind is not the source of its own thoughts and intentions. This discloses the real mystery of free will: if our moment to moment experience is compatible with its utter absence, how can we say that we see any evidence for it in the first place?

None of this, however, renders the choices we make in life any less important. As my friend Dan Dennett has pointed out, many people confuse determinism with fatalism. This gives rise to questions like, "If everything is determined, why should I do anything? Why not just sit back and see what happens?" But the fact that our choices depend on prior causes does not mean that they do not matter. If I had not decided to write my last book, it wouldn't have written itself. My choice to write it was unquestionably the primary cause of its coming into being. Decisions, intentions, efforts, goals, willpower, etc., are causal states of the brain, leading to specific behaviors, and behaviors lead to outcomes in the world. Human choice, therefore, is as important as fanciers of free will believe. And to "just sit back and see what happens" is itself a choice that will produce its own consequences. It is also extremely difficult to do: just try staying in bed all day waiting for something to happen; you will find yourself assailed by the impulse to get up and do something, which will require increasingly heroic efforts to resist.

Therefore, while it is true to say that a person would have done otherwise if he had chosen to do otherwise, this does not deliver the kind of free will that most people seem to cherish—because a person's "choices" merely appear in his mental stream as though sprung from the void. From the perspective of your conscious mind, you are no more responsible for the next thing you think (and therefore do) than you are for the fact that you were born into this world.

Our belief in free will seems to arise from our moment-to-moment ignorance of the specific prior causes of our thoughts and actions. The phrase "free will" describes what it feels like to be identified with the content of each mental state as it arises in consciousness. Trains of thought like, "What should I get my daughter for her birthday? I know, I'll take her to a pet store and have her pick out some tropical fish," convey the apparent reality of choices, freely made. But from a deeper perspective (speaking both subjectively and objectively), thoughts simply arise (what else could they do?) unauthored, and yet author to our actions.

In the philosophical literature, one finds three approaches to the problem of free will: determinism, libertarianism, and compatibilism. Both determinism and libertarianism are often referred to as "incompatibilist" views, in that both maintain that if our behavior is fully determined by background causes, free will is an illusion. Determinists believe that we live in precisely such a world; libertarians (no relation to the political view that goes by this name) believe that our agency rises above the field of prior causes—and they inevitably invoke some metaphysical entity, like a soul, as the vehicle for our freely acting wills. Compatibilists, like Dan Dennett, maintain that free will is compatible with causal determinism (see his fine books, Freedom Evolves and Elbow Room; for other compatibilist arguments see Ayer, Chisholm, Strawson, Frankfurt, Dennett, and Watson here).

The problem with compatibilism, as I see it, is that it tends to ignore that people's moral intuitions are driven by a deeper, metaphysical notion of free will. That is, the free will that people presume for themselves and readily attribute to others (whether or not this freedom is, in Dennett's sense, "worth wanting") is a freedom that slips the influence of impersonal, background causes. The moment you show that such causes are effective—as any detailed account of the neurophysiology of human thought and behavior would— proponents of free will can no longer locate a plausible hook upon which to hang their notions of moral responsibility. The neuroscientists Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen make this same point:

Most people's view of the mind is implicitly dualist and libertarian and not materialist and compatibilist . . . [I]ntuitive free will is libertarian, not compatibilist. That is, it requires the rejection of determinism and an implicit commitment to some kind of magical mental causation . . . contrary to legal and philosophical orthodoxy, determinism really does threaten free will and responsibility as we intuitively understand them (Greene J & J. Cohen. 2004).

It is generally argued that our sense of free will presents a compelling mystery: on the one hand, it is impossible to make sense of in causal terms; on the other, we feel that we are the authors of our own actions. However, I think that this mystery is itself a symptom of our confusion. It is not that free will is simply an illusion: our experience is not merely delivering a distorted view of reality; rather, we are mistaken about the character of our experience. We do not feel as free as we think we do. Our sense of our own freedom results from our not paying close attention to what it is like to be ourselves in the world. The moment we do pay attention, we begin to see that free will is nowhere to be found, and our subjectivity is perfectly compatible with this truth. Thoughts and intentions simply arise in the mind. What else could they do? The truth about us is stranger than many suppose: the illusion of free will is itself an illusion.

May 30, 2011

Morality Without "Free Will"

(Photo by H.koppdelaney)

Many people seem to believe that morality depends for its existence on a metaphysical quantity called "free will." This conviction is occasionally expressed—often with great impatience, smugness, or piety—with the words, "ought implies can." Like much else in philosophy that is too easily remembered (e.g. "you can't get an ought from an is."), this phrase has become an impediment to clear thinking.

In fact, the concept of free will is a non-starter, both philosophically and scientifically. There is simply no description of mental and physical causation that allows for this freedom that we habitually claim for ourselves and ascribe to others. Understanding this would alter our view of morality in some respects, but it wouldn't destroy the distinction between right and wrong, or good and evil.

The following post has been adapted my discussion of this topic in The Moral Landscape (pp. 102-110):

—

We are conscious of only a tiny fraction of the information that our brains process in each moment. While we continually notice changes in our experience—in thought, mood, perception, behavior, etc.—we are utterly unaware of the neural events that produce these changes. In fact, by merely glancing at your face or listening to your tone of voice, others are often more aware of your internal states and motivations than you are. And yet most of us still feel that we are the authors of our own thoughts and actions.

The problem is that no account of causality leaves room for free will—thoughts, moods, and desires of every sort simply spring into view—and move us, or fail to move us, for reasons that are, from a subjective point of view, perfectly inscrutable. Why did I use the term "inscrutable" in the previous sentence? I must confess that I do not know. Was I free to do otherwise? What could such a claim possibly mean? Why, after all, didn't the word "opaque" come to mind? Well, it just didn't—and now that it vies for a place on the page, I find that I am still partial to my original choice. Am I free with respect to this preference? Am I free to feel that "opaque" is the better word, when I just do not feel that it is the better word? Am I free to change my mind? Of course not. It can only change me.

There is a distinction between voluntary and involuntary actions, of course, but it does nothing to support the common idea of free will (nor does it depend upon it). The former are associated with felt intentions (desires, goals, expectations, etc.) while the latter are not. All of the conventional distinctions we like to make between degrees of intent—from the bizarre neurological complaint of alien hand syndrome to the premeditated actions of a sniper—can be maintained: for they simply describe what else was arising in the mind at the time an action occurred. A voluntary action is accompanied by the felt intention to carry it out, while an involuntary action isn't. Where our intentions themselves come from, however, and what determines their character in every instant, remains perfectly mysterious in subjective terms. Our sense of free will arises from a failure to appreciate this fact: we do not know what we will intend to do until the intention itself arises. To see this is to realize that you are not the author of your thoughts and actions in the way that people generally suppose. This insight does not make social and political freedom any less important, however. The freedom to do what one intends, and not to do otherwise, is no less valuable than it ever was.

While all of this can sound very abstract, it is important to realize that the question of free will is no mere curio of philosophy seminars. A belief in free will underwrites both the religious notion of "sin" and our enduring commitment to retributive justice. The Supreme Court has called free will a "universal and persistent" foundation for our system of law, distinct from "a deterministic view of human conduct that is inconsistent with the underlying precepts of our criminal justice system" (United States v. Grayson, 1978). Any scientific developments that threatened our notion of free will would seem to put the ethics of punishing people for their bad behavior in question.

The great worry is that any honest discussion of the underlying causes of human behavior seems to erode the notion of moral responsibility. If we view people as neuronal weather patterns, how can we coherently speak about morality? And if we remain committed to seeing people as people, some who can be reasoned with and some who cannot, it seems that we must find some notion of personal responsibility that fits the facts.

Happily, we can. What does it really mean to take responsibility for an action? For instance, yesterday I went to the market; as it turns out, I was fully clothed, did not steal anything, and did not buy anchovies. To say that I was responsible for my behavior is simply to say that what I did was sufficiently in keeping with my thoughts, intentions, beliefs, and desires to be considered an extension of them. If, on the other hand, I had found myself standing in the market naked, intent upon stealing as many tins of anchovies as I could carry, this behavior would be totally out of character; I would feel that I was not in my right mind, or that I was otherwise not responsible for my actions. Judgments of responsibility, therefore, depend upon the overall complexion of one's mind, not on the metaphysics of mental cause and effect.

Consider the following examples of human violence:

A four-year-old boy was playing with his father's gun and killed a young woman. The gun had been kept loaded and unsecured in a dresser drawer.

A twelve-year-old boy, who had been the victim of continuous physical and emotional abuse, took his father's gun and intentionally shot and killed a young woman because she was teasing him.

A twenty-five-year-old man, who had been the victim of continuous abuse as a child, intentionally shot and killed his girlfriend because she left him for another man.

A twenty-five-year-old man, who had been raised by wonderful parents and never abused, intentionally shot and killed a young woman he had never met "just for the fun of it."

A twenty-five-year-old man, who had been raised by wonderful parents and never abused, intentionally shot and killed a young woman he had never met "just for the fun of it." An MRI of the man's brain revealed a tumor the size of a golf ball in his medial prefrontal cortex (a region responsible for the control of emotion and behavioral impulses).

In each case a young woman has died, and in each case her death was the result of events arising in the brain of another human being. The degree of moral outrage we feel clearly depends on the background conditions described in each case. We suspect that a four-year-old child cannot truly intend to kill someone and that the intentions of a twelve-year-old do not run as deep as those of an adult. In both cases 1 and 2, we know that the brain of the killer has not fully matured and that all the responsibilities of personhood have not yet been conferred. The history of abuse and precipitating cause in example 3 seem to mitigate the man's guilt: this was a crime of passion committed by a person who had himself suffered at the hands of others. In 4, we have no abuse, and the motive brands the perpetrator a psychopath. In 5, we appear to have the same psychopathic behavior and motive, but a brain tumor somehow changes the moral calculus entirely: given its location, it seems to divest the killer of all responsibility. How can we make sense of these gradations of moral blame when brains and their background influences are, in every case, and to exactly the same degree, the real cause of a woman's death?

It seems to me that we need not have any illusions about a casual agent living within the human mind to condemn such a mind as unethical, negligent, or even evil, and therefore liable to occasion further harm. What we condemn in another person is the intention to do harm—and thus any condition or circumstance (e.g., accident, mental illness, youth) that makes it unlikely that a person could harbor such an intention would mitigate guilt, without any recourse to notions of free will. Likewise, degrees of guilt could be judged, as they are now, by reference to the facts of the case: the personality of the accused, his prior offenses, his patterns of association with others, his use of intoxicants, his confessed intentions with regard to the victim, etc. If a person's actions seem to have been entirely out of character, this will influence our sense of the risk he now poses to others. If the accused appears unrepentant and anxious to kill again, we need entertain no notions of free will to consider him a danger to society.

Why is the conscious decision to do another person harm particularly blameworthy? Because consciousness is, among other things, the context in which our intentions become available to us. What we do subsequent to conscious planning tends to most fully reflect the global properties of our minds—our beliefs, desires, goals, prejudices, etc. If, after weeks of deliberation, library research, and debate with your friends, you still decide to kill the king—well, then killing the king really reflects the sort of person you are.

While viewing human beings as forces of nature does not prevent us from thinking in terms of moral responsibility, it does call the logic of retribution into question. Clearly, we need to build prisons for people who are intent upon harming others. But if we could incarcerate earthquakes and hurricanes for their crimes, we would build prisons for them as well. The men and women on death row have some combination of bad genes, bad parents, bad ideas, and bad luck—which of these quantities, exactly, were they responsible for? No human being stands as author to his own genes or his upbringing, and yet we have every reason to believe that these factors determine his character throughout life. Our system of justice should reflect our understanding that each of us could have been dealt a very different hand in life. In fact, it seems immoral not to recognize just how much luck is involved in morality itself.

Consider what would happen if we discovered a cure for human evil. Imagine, for the sake of argument, that every relevant change in the human brain can be made cheaply, painlessly, and safely. The cure for psychopathy can be put directly into the food supply like vitamin D. Evil is now nothing more than a nutritional deficiency.

If we imagine that a cure for evil exists, we can see that our retributive impulse is ethically flawed. Consider, for instance, the prospect of withholding the cure for evil from a murderer as part of his punishment. Would this make any sense at all? What could it possibly mean to say that a person deserves to have this treatment withheld? What if the treatment had been available prior to his crime? Would he still be responsible for his actions? It seems far more likely that those who had been aware of his case would be indicted for negligence. Would it make any sense at all to deny surgery to the man in example 5 as a punishment if we knew the brain tumor was the proximate cause of his violence? Of course not. The urge for retribution, therefore, seems to depend upon our not seeing the underlying causes of human behavior.

Despite our attachment to notions of free will, most us know that disorders of the brain can trump the best intentions of the mind. This shift in understanding represents progress toward a deeper, more consistent, and more compassionate view of our common humanity—and we should note that this is progress away from religious metaphysics. Few concepts have offered greater scope for human cruelty than the idea of an immortal soul that stands independent of all material influences, ranging from genes to economic systems. And yet one of the fears surrounding our progress in neuroscience is that this knowledge will dehumanize us.

Could thinking about the mind as the product of the physical brain diminish our compassion for one another? While it is reasonable to ask this question, it seems to me that, on balance, soul/body dualism has been the enemy of compassion. The moral stigma that still surrounds disorders of mood and cognition seems largely the result of viewing the mind as distinct from the brain. When the pancreas fails to produce insulin, there is no shame in taking synthetic insulin to compensate for its lost function. Many people do not feel the same way about regulating mood with antidepressants (for reasons that appear quite distinct from any concern about potential side effects). If this bias has diminished in recent years, it has been because of an increased appreciation of the brain as a physical organ.

However, the issue of retribution is a genuinely tricky one. In a fascinating article in The New Yorker, Jared Diamond writes of the high price we often pay for leaving vengeance to the state. He compares the experience of his friend Daniel, a New Guinea highlander, who avenged the death of a paternal uncle and felt exquisite relief, to the tragic experience of his late father-in-law, who had the opportunity to kill the man who murdered his family during the Holocaust but opted instead to turn him over to the police. After spending only a year in jail, the killer was released, and Diamond's father-in-law spent the last sixty years of his life "tormented by regret and guilt." While there is much to be said against the vendetta culture of the New Guinea Highlands, it is clear that the practice of taking vengeance answers to a common psychological need.

We are deeply disposed to perceive people as the authors of their actions, to hold them responsible for the wrongs they do us, and to feel that these debts must be repaid. Often, the only compensation that seems appropriate requires that the perpetrator of a crime suffer or forfeit his life. It remains to be seen how the best system of justice would steward these impulses. Clearly, a full account of the causes of human behavior should undermine our natural response to injustice, at least to some degree. It seems doubtful, for instance, that Diamond's father-in- law would have suffered the same pangs of unrequited vengeance if his family had been trampled by an elephant or laid low by cholera. Similarly, we can expect that his regret would have been significantly eased if he had learned that his family's killer had lived a flawlessly moral life until a virus began ravaging his medial prefrontal cortex.

It may be that a sham form of retribution could still be moral, if it led people to behave far better than they otherwise would. Whether it is useful to emphasize the punishment of certain criminals—rather than their containment or rehabilitation—is a question for social and psychological science. But it seems clear that a desire for retribution, based upon the idea that each person is the free author of his thoughts and actions, rests on a cognitive and emotional illusion—and perpetuates a moral one.

Sam Harris's Blog

- Sam Harris's profile

- 9007 followers

.

. .

.